The Hawaiian

Archipelago:

Six months amongst the

palm groves, coral reefs, and volcanoes of the Sandwich Islands

By Isabella L. Bird, 1875

LETTER 13

|

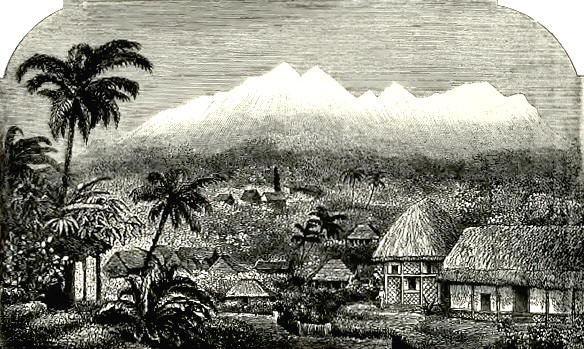

A Royal Landing—The Royal Procession—Puna Woods—Lunalilo—The Hookupu — Loyal Enthusiasm — The Gift-bearers—The Gifts—The King's Speech Hilo, Hawaii, February The quiet, dreamy, afternoon existence of Hilo is disturbed. Two days ago an official intimation was received that the American Government had placed the U. S. ironclad " Benicia" at the disposal of King Lunalilo for a cruise round Hawaii, and that he would arrive here the following morning with Admiral Pennock and the U. S. generals Scholneld and Alexander. Now this monarchy is no longer an old-time chieftaincy, made up of calabashes and poi^ leather-cloaks, kahilis, and a little fuss, but has a civilized constitutional king, the equal of Queen Victoria, a civil list, &c, and though Lunalilo comes here trying to be a private individual and to rest from Hookupus, state entertainments, and privy councils, he brings with him a royal chamberlain and an adjutant-general in attendance. So the good people of Hilo have been decorating their houses anew with ferns and flowers, furbishing up their clothes, and holding mysterious consultations regarding etiquette and entertainments, just as if royalty were about to drop down in similar fashion on Bude or Tobermory. There were amusing attempts to bring about a practical reconciliation between the free-and easiness of Republican notions and the respect due to a sovereign who reigns by "the will of the people" as well as by "the grace of God," but eventually the tact of the king made everything go smoothly. At eight yesterday morning the " Benicia " anchored inside the reef, and Hilo blossomed into a most striking display of bunting; the Hawaiian colours, eight blue, red and white stripes, with the English union in the corner, and the flaunting flag of America being predominant. My heart warmed towards our own flag as the soft breeze lifted its rich folds among the glories of the tropical trees. Indeed, bunting to my mind never looked so well as when floating and fainting among cocoanut palms and all the shining greenery of Hilo, in the sunshine of a radiant morning. It was bright and warm, but the cool bulk of Mauna Kea, literally covered with snow, looked down as winter upon summer. Natives galloped in from all quarters, brightly dressed, wreathed, and garlanded, delighted in their hearts at the attention paid to their sovereign by a great foreign power, though they had been very averse to this journey, from a strange but prevalent idea that once on board a U. S. ship the king would be kidnapped and conveyed to America. Lieut-Governor Lyman and Mr. Severance, the sheriff, went out to the "Benicia," and the king landed at ten o'clock, being "graciously pleased" to accept the Governor's house as his residence during his visit. The American officers, naval and military, were received by the same loud, hospitable old whaling captain who entertained the Duke of Edinburgh some years ago here, and to judge from the hilarious sounds which came down the road from his house, they had what they would call " a good time." I had seen Lunalilo in state at Honolulu, but it was much more interesting to see him here, and this royalty is interesting in itself, as a thing on sufferance, standing between this helpless nationality and its absorption by America. The king is a very fine-looking man of thirty-eight, tall, well formed, broad-chested, with his head well set on his shoulders, and his feet and hands small. His appearance is decidedly commanding and aristocratic: he is certainly handsome even according to our notions. He has a fine open brow, significant at once of brains and straightforwardness, a straight, proportionate nose, and a good mouth. The slight tendency to Polynesian overfulness about his lips is concealed by a well-shaped moustache. He wears whiskers cut in the English fashion. His eyes are large, dark-brown of course, and equally of course, he has a superb set of teeth. Owing to a slight fulness of the lower eyelid, which Queen Emma also has, his eyes have a singularly melancholy expression, very alien, I believe, to his character. He is remarkably gentlemanly looking, and has the grace of movement which seems usual with Hawaiians. When he landed he wore a dark morning suit and a black felt hat.

As soon as he stepped on shore, the natives, who were in crowds on the beach, cheered, yelled, and waved their hats and handkerchiefs, and then a procession was formed, or rather formed itself, to escort him to the governor's house. A rabble of children ran in front, then came the king, over whom the natives had thrown some beautiful garlands of ohia and maile (Alyxia olivceformis), with the governor on one side and the sheriff on the other, the chamberlain and adjutant-general walking behind. Then a native staggering under the weight of an enormous Hawaiian flag, the Hiio band, with my friend Upa beating the big drum, and an irregular rabble (unorganised crowd) of men, women, and children, going at a trot to keep up with the king's rapid strides. The crowd was unwilling to disperse even when he entered the house, and he came out and made a short speech, the gist of which was that he was delighted to see his native subjects, and would hold a reception for them on the ensuing Monday, when we shall see a most interesting sight, a native crowd gathered from all Southern Hawaii for a hookupu, an old custom, signifying the bringing of gift-offerings to a king or chief. In the afternoon Dr. Wetmore and I rode to the beautiful Puna woods on a botanising excursion. We were galloping down to the beach round a sharp corner, when we had to pull our horses almost on their haunches to avoid knocking over the king, the American admiral, the captain of the "JBenicia," nine of their officers, and the two generals. When I saw the politely veiled stare of the white men it occurred to me that probably it was the first time that they had seen a white woman riding cavalier fashion ! We had a delicious gallop over the sands to the Waiakea river, which we crossed, and came upon one of the vast lava-flows of ages since, over which we had to ride carefully, as the pahoehoe lies in rivers, coils, tortuosities, and holes partially concealed by a luxuriant growth of ferns and convolvuli. The country is thickly sprinkled with cocoanut and breadfruit trees, which merge into the dense, dark, glorious forest, which tenderly hides out of sight hideous, broken lava, on which one cannot venture six feet from the track without the risk of breaking one's limbs. All these tropical forests are absolutely impenetrable, except to axe and billhook, and after a trail has been laboriously opened, it needs to be cut once or twice a year, so rapid is the growth of vegetation. This one, through the Puna woods, only admits of one person at a time. It was really rapturously lovely. Through the trees we saw the soft steel-blue of the summer sky: not a leaf stirred, not a bird sang, a hush had fallen on insect life, the quiet was perfect, even the ring of our horses' hoofs on the lava was a discord. There was a slight coolness in the air and a fresh mossy smell. It only required some suggestion of decay, and the rustle of a fallen leaf now and then, to make it an exact reproduction of a fine day in our English October. The forest was enlivened by many natives bound for Hilo, driving horses loaded with cocoanuts, breadfruit, live fowls, poi and kalo, while others with difficulty urged garlanded pigs in the same direction, all as presents for the king. We brought back some very scarce parasitic ferns. Hilo, February 24th I rode over by myself to Onomea on Saturday to get a little rest from the excitements of Hilo. A gentleman lent me a strong, showy mare to go out on, telling me that she was frisky and must be held while I mounted; but before my feet were fairly in the stirrups, she shook herself from the Chinaman who held her, and danced away. I rode her five miles before she quieted down. She pranced, jumped, danced, and fretted on the edge of precipices, was furious at the scow and fords, and seemed demented with good spirits. Onomea looked glorious, and its serenity was most refreshing. I rode into Hilo the next day in time for morning service, and the mare, after a good gallop, subsided into a staidness of demeanour befitting the day. Just as I was leaving, they asked me to take the news to the sheriff that a man had been killed a few hours before. He was riding into Hilo with a child behind him, and they went over by no means one of the worst of the palis. The man and horse were killed, but the child was unhurt, and his wailing among the deep ferns attracted the attention of passers-by to the disaster. The natives ride over these dangerous polls so carelessly, and on such tired, starved horses, that accidents are not infrequent. Hilo had never looked so lovely to me as in the pure, bright calm of this Sunday morning. The verandahs of all the native houses were crowded with strangers, who had come in to share in the jubilations attending the king's visit. At the risk of emulating "Jenkins," or the " Court Newsman," I must tell you that Lunalilo, who is by no means an habitual church-goer, attended Mr. Coan's native church in the morning, and the foreign church at night, when the choir sang a very fine anthem. I don't wish to write about his faults, which have doubtless been rumoured in the English papers. It is hoped that his new responsibilities will assist him to conquer them, else I fear he may go the way of several of the Hawaiian kings. He has begun his reign with marked good sense in selecting as his advisers confessedly the best men in his kingdom, and all his public actions since his election have shown both tact and good feeling. If sons, as is often asserted, take their intellects from their mothers, he should be decidedly superior, for his mother, Kekauluohi, a chieftainess of the highest rank, and one of the queens of Kamehameha II., who died in London, was in 1839 chosen for her abilities by Kamehameha III., as his kuhina nut, or premier, an officer recognised under the old system of Hawaiian government as second only in authority to the king, and without whose signature even his act was not legal. As Kaahumanu II she continued to hold this important position until her death in l845. But the present king does not come of the direct line of the Hawaiian kings, but of a far older family. His father is a commoner, but Hawaiian rank is inherited through the mother. He received a good English education at the school which the missionaries established for the sons of chiefs, and was noted as a very bright scholar, with an early developed taste for literature and poetry. His disposition is said to be most amiable and genial, and his affability endeared him especially to his own countrymen, by whom he was called alii lokomaikai, "the kind chief." In spite of his high rank, which gave him precedence of all others on the islands, he was ignored by two previous governments, and often complained that he was never allowed any opportunity of becoming acquainted with public affairs, or of learning whether he possessed any capacity for business. Thus, without experience, but with noble and liberal instincts, and the highest and most patriotic aspirations for the welfare and improvement of his " weak little kingdom," he was unexpectedly called to the throne about three months ago, amidst such an enthusiasm as had never before been witnessed on Hawaii-nei, as the unanimous choice of the people. He called on Mr. Coan the day of his arrival; and when the flute band of Mr. Lyman's school serenaded him, he made the youths a kind address, in which he said he had been taught as they were, and hoped hereafter to profit by the instruction he had received. This has been a great day in Hilo. The old native custom of hookupu was revived, and it has been a most interesting spectacle. I don't think I ever enjoyed sight-seeing so much. The weather has been splendid, which was most fortunate, for many of the natives came in from distances of from sixty to eighty miles. From early daylight they trooped in on their half broken steeds, and by ten o'clock there were fully a thousand horses tethered on the grass by the sea. Almost every house displayed flags, and the court-house, where the reception was to take place, was most tastefully decorated. It is a very pretty two-storied frame building, with deep double verandahs, and stands on a large lawn of fine mainienie grass, with roads on three sides. Long before ten, crowds had gathered outside the low walls of the lawn, natives and foreigners galloped in all directions, boats and canoes enlivened the bay, bands played, and the foreigners, on this occasion rather a disregarded minority, assembled in holiday dress in the upper verandah of the court-house. Hawaiian flags on tall bamboos decorated the little gateways which gave admission to the lawn, an enormous standard on the government flagstaff could be seen for miles, and the stars and stripes waved from the neighbouring plantations and from several houses in Hilo. At ten punctually, Lunalilo, Governor Lyman, the sheriff of Hawaii, the royal chamberlain, and the adjutant-general, walked up to the courthouse, and the king took his place, standing in the lower verandah with his suite about him. All the foreigners were either on the upper balcony, or on the stairs leading to it, on which, to get the best possible view of the spectacle, I stood for three mortal hours. The attendant gentlemen were well dressed, but wore "shocking bad hats;" and the king wore a sort of shooting suit, a short brown cut-away coat, an ash-coloured waistcoat and ash-coloured trousers with a blue stripe. He stood bareheaded. He dressed in this style in order that the natives might attend the reception in every- day dress, and not run the risk of spoiling their best clothes by Hilo torrents. The dress of the king and his attendants was almost concealed by wreaths of ohia blossoms and festoons oimaile, some of them two yards long, which had been thrown over them, and which bestowed a fantastic glamour on the otherwise prosaic inelegance of their European dress. But indeed the spectacle, as a whole, was altogether poetical, as it was an ebullition of natural, national, human feeling, in which the heart had the first place. I very soon ceased to notice the incongruous elements, which were supplied chiefly by the Americans present. There were Republicans by birth and nature, destitute of traditions of loyalty or reverence for aught on earth; who bore on their faces not only republicanism, but that quintessence of puritan republicanism which hails from New England; and these were subjects of a foreign king, nay, several were office-holders who had taken the oath of allegiance, and from whose lips "His Majesty, Your Majesty," flowed far more copiously than from ours which are "to the manner born." On the king's appearance, the cheering was tremendous,— regular British cheering, well led, succeeded by that which is not British, "three cheers and a tiger," but it was "Hi, hi, hi, nullah!" Every hat was off, every handkerchief in air, tears in many eyes, enthusiasm universal, for the people were come to welcome the king of their choice; the prospective restorer of the Constitution "trampled upon" by Kamehameha V., " the kind chief," who was making them welcome to his presence after the fashion of their old feudal lords. When the cheering had subsided, the eighty boys of Missionary Lyman's School, who, dressed in white linen with crimson lets, were grouped in a hollow square round the flagstaff, sang the Hawaiian national anthem, the music of which is the same as ours. More cheering and enthusiasm, and then the natives came through the gate across the lawn, and up to the verandah where the king stood, in one continuous procession, till 2,400 Hawaiians had enjoyed one moment of infinite and ever to be remembered satisfaction in the royal presence. Every now and then the white, pale-eyed, unpicturesque face of a foreigner passed by, but these were few, and the foreign school children were received by themselves after Mr. Lyman's boys. The Americans have introduced the villanous custom of shaking hands at these receptions, borrowing it, I suppose, from a presidential reception at Washington; and after the king had gone through this ceremony with each native, the present was deposited in front of the verandah, and the gratified giver took his place on the grass. Not a man, woman, or child came empty handed. Every face beamed with pride, wonder, and complacency, for here was a sovereign for whom cannon roared, and yards were manned, of their own colour, who called them his brethren. The variety of costume was infinite. All the women wore the native dress, the sack or holoku, many of which were black, blue, green, or bright rose colour, some were bright yellow, a few were pure white, and others were a mixture of orange and scarlet. Some wore very pretty hats made from cane-tops, and trimmed with hibiscus blossoms or passion-flowers; others wore bright-coloured handkerchiefs, knotted lightly round their flowing hair, or wreaths of the Microlepia tenuifolia. Many had tied bandanas in a graceful knot over the left shoulder. All wore two, three, four, or even six beautiful Zeis, besides long festoons of the fragrant maile. Leis of the crimson ohia blossoms were universal; but besides these there were let's of small red and white double roses, pohas yellow amaranth, sugar cane tassels like frosted silver, the orange pandanus, the delicious gardenia, and a very few of orange blossoms, and the great granadilla or passion-flower. Few if any of the women wore shoes, and none of the children had anything on their heads. A string of 200 Chinamen passed by, "plantation hands," with boyish faces, and cunning, almond-shaped eyes. They were dressed in loose, blue, denim trousers with shirts of the same, fastening at the side over them, their front hair closely shaven, and the rest gathered into pigtails, which were wound several times round their heads. These all deposited money in the adjutant-general's hand. The dress of the Hawaiian men was more varied and singular than that of the women, every kind of dress and undress, with lets of ohia and garlands of maile covering all deficiencies. The poor things came up with pathetic innocence, many of them with nothing on but an old shirt, and cotton trousers rolled up to the knees. Some had red shirts and blue trousers, others considered that a shirt was an effective outer garment. Some wore highly ornamental, dandified shirts, and trousers tucked into high, rusty, mud-covered boots. A few young men were in white straw hats, white shirts, and white trousers, with crimson lets round their hats and throats. Some had diggers' scarves round their waists; but the most effective costume was sported by a few old men, who had tied crash towels over their shoulders. It was often amusing and pathetic at once to see them come up. Obviously, when the critical moment arrived, they were as anxious to do the right thing as a debutante is to back her train successfully out of the royal presence at St. James's. Some were so agitated at last as to require much coaching from the governor as to how to present their gifts and shake hands. Some half dropped down on their knees, others passionately and with tears kissed the king's hand, or grasped it convulsively in both their own; while a few were so embarrassed by the presents they were carrying that they had no hands at all to shake, and the sovereign good-naturedly clapped them on the shoulders. Some of them, in shaking hands, adroitly slipped coins into the king's palm, so as to make sure that he received their loving tribute. There had been a hui, or native meeting, which had passed resolutions, afterwards presented to Lunalilo, setting forth that whereas he received a great deal of money in revenue from the haoles, they, his native people, would feel that he did not love them if he would not receive from then own hands contributions in silver for his support. So, in order not to wound their feelings, he accepted these rather troublesome cash donations. One woman, sorely afflicted with quaking palsy, dragged herself slowly along. One hand hung by her side helpless, and the other grasped a live fowl so tightly that she could not loosen it to shake hands, whereupon the king raised the helpless arm, which called forth much cheering. There was one poor cripple who had only the use of his arms. His knees were doubled under him, and he trailed his body along the ground. He had dragged himself two miles " to lie for a moment at the king's feet," and even his poor arms carried a gift. He looked hardly like a human shape, as his desire was realised; and, I doubt not, would have been content then and there to die. There were ancient men, tattooed all over, who had passed their first youth when the idols were cast away, and who remembered the old days of tyranny when it was an offence, punishable with death, for a man to let his shadow fall on the king; and when none of " the swinish multitude " had any rights which they could sustain against their chiefs. These came up bewildered, trembling, almost falling on their knees, hardly daring to raise their eyes to the king's kind, encouraging face, and bathed his hand .with tears while they kissed it. Numbers of little children were led up by their parents; there were babies in arms, and younglings carried on parents' backs, and the king stooped and shook hands with all, and even pulled out the babies' hands from under their mufflings and the old people wept, and cheers rent the air. Next in interest to this procession of beaming faces, and the blaze of colour, was the sight of the presents, and the ungrudging generosity with which they were brought. Many of the women presented live fowls tied by the legs, which were deposited, one upon another, till they formed a fainting, palpitating heap under the hot sun. Some of the men brought decorated hogs tied by one leg, which squealed so persistently in the presence of royalty, that they were removed to the rear. Hundreds carried nets of sweet potatoes, eggs, and kalo, artistically arranged. Men staggered along in couples with bamboos between them, supporting clusters of bananas weighing nearly a hundredweight. Others brought yams, cocoanuts, oranges, onions, pumpkins, early pineapples, and even the great, delicious fruit of the large passion-flower. A few maidens presented the king with bouquets of choice flowers, and costly his of the yellow feathers of the Melithreptes Pacifica. There were fully two tons of kalo and sweet potatoes in front of the court house, hundreds of fowls, and piles of bananas, eggs, and cocoanuts. The hookupu was a beautiful sight, all the more so that not one of that radiant, loving, gift-offering throng came in quest of office, or for any other thing that he could obtain. It was just the old-time spirit of reverence for the man who typifies rule, blended with the extreme of personal devotion to the prince whom a united people had placed upon the throne. The feeling was genuine and pathetic in its intensity. It is said that the natives like their king better, because he was truly, " above all," the last of a proud and imperious house, which, in virtue of a pedigree of centuries, looked down upon the nobility of the Kamehamehas. When the last gift was deposited, the lawn in front of the court-house was one densely-packed, variegated mass of excited, buzzing Hawaiians. While the king was taking a short rest, two ancient and hideous females, who looked like heathen priestesses, chanted a monotonous and heathenish-sounding chant or mile, in eulogy of some ancient idolater. It just served to remind me that this attractive crowd was but one generation removed from slaughter-loving gods and human sacrifices. The king and his suite re-appeared in the upper balcony, where all the foreigners were assembled, including the two venerable missionaries and a French priest of benign aspect, and his appearance was the signal for a fresh outburst of enthusiasm. Advancing to the front, he made an extemporaneous speech, of which the following is a literal translation:— "To all present I tender my warmest aloha. This day, on which you are gathered to pay your respects to me, I will remember to the day of my death. (Cheers.) I am filled with love to you all, fellow-citizens (makaainana) who have come here on this occasion, and for all the people, because by your unanimous choice I have been made your King, a young sovereign, to reign over you, and to fill the very distinguished office which I now occupy. (Cheers.) You are parents to me, and I will be your Father. (Tremendous cheering.) Formerly, in the days of our departed ancestors, you were not permitted to approach them; they and you were kept apart; but now we meet and associate together. (Cheers). I urge you all to persevere in the right, to forsake the ignorant ways of the olden time. There is but one God, whom it is our duty to obey. Let us forsake every kind of idolatry. In the year 1820 Rev. Messrs. Bingham, Thurston, and others came to these Islands and proclaimed the Word of God. It is their teachings which have enabled you to be what you are to-day. Now they have all gone to that spirit land, and only Mrs. Thurston remains. We are greatly indebted to them. (Cheers.) There are also among us here (alluding to Revs. Coan and Lyman) old and grey-haired fathers, whose examples we should endeavour to imitate, and obey their teachings. I am very glad to see the young men of the present time so well instructed in knowledge—perhaps some of them are your children. You must persevere in your search of wisdom and in habits of morality. Do not be indolent. (Cheers.) Those who have striven hard after knowledge and good character, are the ones who deserve and shall receive places of trust hereafter under the government. At the present time I have four foreigners as my ministerial advisers. But if, among these young men now standing before me, and under this flag, there are any who shall qualify themselves to fill these positions, then I will select them to fill their places. (Loud cheers.) Aloha to you all." His manner as a speaker was extremely good, with sufficient gesticulation for the emphasis of particular points. The address was frequently interrupted by applause, and when at its conclusion he bowed gracefully to the crowd and said, "My aloha to you all," the cheering and enthusiasm were absolutely unbounded. And so the great hookupu ended, and the assemblage broke up into knots to discuss the royal speech and the day's doings, I.L.B |

||

|

Letter 14: Cookery, Lunalilo's Intelligence, a Hilo "At Home," and the last of Upa |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |