The Hawaiian

Archipelago:

Six months amongst the

palm groves, coral reefs, and volcanoes of the Sandwich Islands

By Isabella L. Bird, 1875

LETTER 19

|

Hawaiian Women—The Honolulu Market—Annexation and Reciprocity —The “Rolling Moses"

Hawaiian Hotel, Honolulu

My latest news of you is five months old, and though I have not the slightest expectation that I shall hear from you, I go up to the roof to look out for the "Rolling Moses" with more impatience and anxiety than those whose business journeys are being delayed by her non-arrival. If such an unlikely thing were to happen as that she were to bring a letter, I should be much tempted to stay five months longer on the islands rather than try the climate of Colorado, for I have come to feel at home, people are so very genial, and suggest so many plans for my future enjoyment, the islands in their physical and social aspects are so novel and interesting, and the climate is unrivalled and restorative.

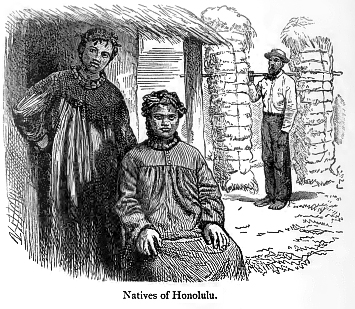

Honolulu has not yet lost the charm of novelty for me. I am never satiated with its exotic beauties, and the sight of a kaleidoscopic whirl of native riders is always fascinating. The passion for riding, in a people who only learned equitation in the last generation, is most curious. It is very curious, too, to see women incessantly enjoying and amusing themselves in riding, swimming, and making leis. They have few home ties in the shape of children, and I fear make them fewer still by neglecting them for the sake of riding and frolic, and man seems rather the helpmeet than the "oppressor" of woman; though I believe that the women have abandoned that right of choosing their husbands, which, it is said, that they exercised in the old days. Used to the down-trodden look and harassed, care-worn faces of the over-worked women of the same class at home and in the colonies, the laughing, careless faces of the Hawaiian women have the effect upon me of a perpetual marvel. But the expression generally has little of the courteousness, innocence, and childishness of the negro physiognomy. The Hawaiians are a handsome people, scornful and sarcastic-looking even with their mirthfulness, and those who know them say that they are always quizzing and mimicking the haoles, and that they give every one a nickname founded on some personal peculiarity.

The women are free from our tasteless perversity as to colour and ornament, and have an instinct of the becoming. At first the holoku, which is only a full, yoke nightgown, is not attractive, but I admire it heartily now, and the sagacity of those who devised it. It conceals awkwardness, and befits grace of movement: it is fit for the climate, is equally adapted for walking and riding, and has that general appropriateness which is desirable in costume. The women have a most peculiar walk, with a swinging motion from the hip at each step, in which the shoulder sympathises. I never saw anything at all like it. It has neither the delicate shuffle of the Frenchwoman, the robust, decided jerk of the Englishwoman, the stately glide of the Spaniard, or the stealthiness of the squaw, and I should know a Hawaiian woman by it in any part of the world. A majestic wahine with small, bare feet, a grand, swinging, deliberate gait, hibiscus blossoms in her flowing hair, and a lei of yellow flowers falling over her holoku, marching through these streets, has a tragic grandeur of appearance, which makes the diminutive, fair-skinned haole, tottering along hesitatingly in high-heeled shoes, look grotesque by comparison.

On Saturday, our kind host took Mrs. D. and myself to the market, where we saw the natives in all their glory. The women, in squads of a dozen at a time, their Pa`us streaming behind them, were cantering up and down the streets, and men and women were thronging into the market-place; a brilliant, laughing, joking crowd, their jaunty hats trimmed with fresh flowers, and leis of the crimson ohia and range lauhala falling over their costumes, which were white, green, black, scarlet, blue, and every other colour that can be dyed or imagined. The market is a straggling, open space, with a number of shabby stalls partially surrounding it, but really we could not see the place for the people. There must have been 2000 there.

Some of the stalls were piled up with wonderful fish, crimson, green, rose, blue, opaline—fish that have spent their lives in coral groves under the warm, bright water. Some of them had wonderful shapes too, and there was one that riveted my attention and fascinated me. It was, I thought at first, a heap, composed of a dog fish, some limpets, and a multitude of water snakes, and other abominable forms j but my eyes slowly informed me of the fact, which I took in reluctantly and with extreme disgust, that the whole formed one living monster, a revolting compound of a large paunch with eyes, and a multitude of nervy, snaky, out-reaching, twining, grasping, tentacular arms, several feet in length, I should think, if extended, but then lying in a crowded undulating heap; the creature was dying, and the iridescence was passing over what seemed to be its body in waves of colour, such as glorify the last hour of the dolphin. But not the colours of the rainbow could glorify this hideous, abominable form, which ought to be left to riot in ocean depths, with its loathsome kindred. You have read "Les Travailleurs du Mer" and can imagine with what feelings I looked upon a living Devil-fish ! The monster is much esteemed by the natives as an article of food, and indeed is generally relished. I have seen it on foreign tables, salted, under the name of squid.*

* This monster is a cephalopod of the order Dibranchiata, and has eight flexible arms, each crowded with 120 pair of suckers, and two longer feelers about six feet in length, differing considerably from the others in form.

We passed on to beautiful creatures, the kihi-kihi, or seacock, with alternate black and yellow transverse bands on his body; the hinalea, like a glorified mullet, with bright green, longitudinal bands on a dark shining head, a purple body of different shapes, and a blue spotted tail with a yellow tip. The ohua too, a pink scaled fish, shaped like a trout; the opukai, beautifully striped and mottled; the mullet and flying fish as common here as mackerel at home; the hala, a fine pink-fleshed fish, the albicore, the bonita, the martini striped black and white, and many others. There was an abundance of opilu or limpets, also the pipi, a. small oyster found among the coral; the ula, as large as a clawless lobster, but more beautiful and variegated; and turtles which were cheap and plentiful. Then there were purple-spiked sea urchins, black-spiked sea eggs or wana, and ina or eggs without spikes, and many other curiosities of the bright Pacific. It was odd to see the pearly teeth of a native meeting in some bright-coloured fish, while the tail hung out of his mouth, for they eat fish raw, and some of them were obviously at the height of epicurean enjoyment. Seaweed and fresh-water weed are much relished by Hawaiians, and there were four or five kinds for sale, all included in the term limit. Some of this was baked, and put up in balls weighing one pound each. There were packages of baked fish, and dried fish, and of many other things which looked uncleanly and disgusting; but no matter what the package was, the leaf of the Ti tree was invariably the wrapping, tied round with sennet, the coarse fibre obtained from the husk of the cocoanut. Fish, here, averages about ten cents, per pound, and is dearer than meat; but in many parts of the islands it is cheap and abundant.

There is a ferment going on in this kingdom, mainly got up by the sugar planters and the interests dependent on them, and two political lectures have lately been given in the large hall of the hotel in advocacy of their views; one, on annexation, by Mr. Phillips, who has something of the oratorical gift of his cousin, Wendell Phillips; and the other, on a reciprocal treaty, by Mr. Carter. Both were crowded by ladies and gentlemen, and the first was most enthusiastically received. Mrs. D. and I usually spend our evenings in writing and working in the verandah, or in each other's rooms; but I have become so interested in the affairs of this little state, that in spite of the mosquitos, I attended both lectures, but was not warmed into sympathy with the views of either speaker.

I daresay that some of my friends here would quarrel with my conclusions, but I will briefly give the data on which they are based. The census of 1872 gives the native population at 49,044 souls; of whom, 700 are lepers; and it is decreasing at the rate of from 1,200 to 2,000 a year, while the excess of native males over females on the islands is 3216. The foreign population is 5,366, and it is increasing at the rate of 200 a year; and the number of half-castes of all nations has increased at the rate of 1 40 a year. The Chinese, who came here originally as plantation coolies, outnumber all the other nationalities together, excluding the Americans; but the Americans constitute the ruling and the monied class. Sugar is the reigning interest on the islands, and it is almost entirely in American hands. It is burdened here by the difficulty of procuring labour, and at San Francisco by a heavy import duty. There are thirty-five plantations on the islands, and there is room for fifty more. The profit, as it is, is hardly worth mentioning, and few of the planters do more than keep their heads above water. Plantations which cost $50,000 have been sold for $15,000; and others which cost $150,000 have been sold for $40,000. If the islands were annexed, and the duty taken off, many of these struggling planters would clear $50,000 a year and upwards. So, no wonder that Mr. Phillips's lecture was received with enthusiastic plaudits. It focussed all the clamour I have heard on Hawaii and elsewhere, exalted the "almighty dollar," and was savoury with the odour of coming prosperity. But he went far, very far; he has aroused a cry among the natives "Hawai`i for the Hawaiians" which, very likely, may breed mischief; for I am very sure that this brief civilization has not quenched the "red fire" of race; and his hint regarding the judicious disposal of the king in the event of annexation, was felt by many of the more sober whites to be highly impolitic.

The reciprocity treaty, very lucidly advocated by Mr. Carter, and which means the cession of a lagoon with a portion of circumjacent territory on this island, to the United States, for a Pacific naval station, meets with more general favour as a safer measure; but the natives are indisposed to bribe the Great Republic to remit the sugar duties by the surrender of a square inch of Hawaiian soil; and, from a British point of view, I heartily sympathise with them.* Foreign, i.e. American feeling is running high upon the subject. People say that things are so bad that something must be done, and it remains to be seen whether natives or foreigners can exercise the strongest pressure on the king. I was unfavourably impressed in both lectures by the way in which the natives and their interests were quietly ignored, or as quietly subordinated to the sugar interest.

* The native feeling on this subject proved strong enough to coerce Lunalilo and the Cabinet, and the idea of ceding Pearl River was abandoned. In 1875 King Kalakaua and Chancellor Allen visited Washington, and a Reciprocity Treaty with America was negotiated on the simple principle of Free Trade. It has not yet come into operation, however, as the United States revenue laws, necessary to make it effective, have not been enacted, and the Hawaiian planters are still in a state of suspense.

It is never safe to forecast destiny; yet it seems most probable that sooner or later in this century the closing catastrophe must come. The more thoughtful among the natives acquiesce helplessly and patiently in their advancing fate j but the less intelligent, as I had some opportunity of hearing at Hilo, are becoming restive and irritable, and may drift into something worse if the knowledge of the annexationist views of the foreigners is diffused among them. Things are preparing for change, and I think that the Americans will be wise in their generation if they let them ripen for many years to come. Lunalilo has a broken constitution, and probably will not live long. Kalakaua will probably succeed him, and "after him the deluge," unless he leaves a suitable successor, for there are no more chiefs with pre-eminent claims to the throne. The feeling among the people is changing, the feudal instinct is disappearing, the old despotic line of the Kamehamehas is extinct; and king-making by paper ballots, introduced a few months ago, is an approximation to president-making, with the canvassing, stumping, and wrangling, incidental to such a contested election. Annexation, or peaceful absorption, is the "manifest destiny" of the islands, with the probable result lately most wittily prophesied by Mark Twain in the New York Tribune, but it is impious and impolitic to hasten it. Much as I like America, I shrink from the day when her universal political corruption and her unrivalled political immorality shall be naturalised on Hawaii-nei.... Sunday evening. The "Rolling Moses" is in, and Sabbatic quiet has given place to general excitement. People thought they heard her steaming in at 4 a.m., and got up in great agitation. Her guns fired during morning service, and I doubt whether I or any other person heard another word of the sermon. The first batch of letters for the hotel came, but none for me; the second, none for me; and I had gone to my room in despair, when some one tossed a large package in at my verandah door, and to my infinite joy I found that one of my benign fellow-passengers in the Nevada, had taken the responsibility of getting my letters at San Francisco and forwarding them here. I don't know how to be grateful enough to the good man. With such late and good news, everything seems bright: and I have at once decided to take the first schooner for the leeward group, and remain four months longer on the islands.

I.L.B |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |