The Hawaiian

Archipelago:

Six months amongst the

palm groves, coral reefs, and volcanoes of the Sandwich Islands

By Isabella L. Bird, 1875

LETTER 2

|

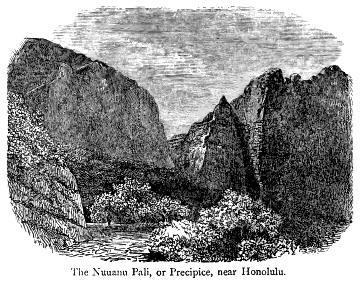

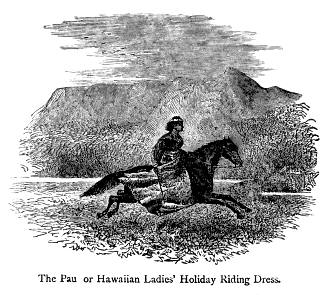

First Impressions of Honolulu—Tropical Vegetation—The Nuuanu Pali—Female Equestrianism—The Hawaiian Hotel—Paradise in the Pacific —Mosquitos Hawaiian Hotel, Honolulu, Jan. 26th Yesterday morning at 6.30 I was aroused by the news that "The Islands" were in sight. Oahu in the distance, a group of grey, barren peaks rising verdureless out of the lonely sea, was not an exception to the rule that the first sight of land is a disappointment. Owing to the clear atmosphere, we seemed only five miles off, but in reality we were twenty, and the land improved as we neared it. It was the fiercest day we had had, the deck was almost too hot to stand upon, the sea and sky were both magnificently blue, and the unveiled sun turned every minute ripple into a diamond flash. As we approached, the island changed its character. There were lofty peaks, truly—grey and red, sun-scorched, and wind-bleached, glowing here and there with traces of their fiery origin; but they were cleft by deep chasms and ravines of cool shade and entrancing greenness, and falling water streaked their sides—a most welcome vision after eleven months of the desert sea, and the dusty browns of Australia and New Zealand. Nearer yet, and the coast line came into sight, fringed by the feathery cocoanut tree of the tropics, and marked by a long line of surf. The grand promontory of Diamond Head, its fiery sides now softened by a haze of green, terminated the wavy line of palms, then the Punchbowl, a perfect, extinct crater, brilliant with every shade of red volcanic ash, blazed against the green skirts of the mountains. We were close to the coral reef before the cry, "There's Honolulu!" made us aware of the proximity of the capital of the island kingdom, and then, indeed, its existence had almost to be taken upon trust, for besides the lovely wooden and grass huts, with deep verandahs, which nestled under palms and bananas on soft green sward, margined by the bright sea sand, only two church spires and a few grey roofs appeared above the trees. We were just outside the reef, and near enough to hear that deep sound of the surf which, through the ever serene summer years girdles the Hawaiian Islands with perpetual thunder, before the pilot glided alongside, bringing the news which Mark Twain had prepared us to receive with interest, that "Prince Bill" had been unanimously elected to the throne. The surf ran white and pure over the environing coral reef, andas we passed through the narrow channel, we almost saw the coral forests deep down under the Nevada's keel; the coral fishers plied their graceful trade; canoes with outriggers rode the combers, and glided with inconceivable rapidity round our ship; amphibious brown beings sported in the transparent waves; and within the reef lay a calm surface of water of a wonderful blue, entered by a narrow, intricate passage of the deepest indigo. And beyond the reef and beyond the blue, nestling among cocoanut trees and bananas, umbrella trees and breadfruits, oranges, mangoes, hibiscus, algaroba, and passion-flowers, almost hidden in the deep, dense greenery, was Honolulu. Bright blossom of a summer sea! Fair Paradise of the Pacific! Inside the reef the magnificent iron-clad California and another large American war vessel, the Benicia, are moored in line with the British corvette Scout, within 200 yards of the shore; and their boats were constantly passing and re-passing, among countless canoes filled with natives. Two coasting schooners were just leaving the harbour, and the inter-island steamer Kilauea, with her deck crowded with natives, was just coming in. By noon the great decrepit Nevada, which has no wharf at which she can lie in New Zealand, was moored alongside a very respectable one in this enterprising little Hawaiian capital. We looked down from the towering deck on a crowd of two or three thousand people—whites, Kanakas, Chinamen—and hundreds of them at once made their way on board, and streamed over the ship, talking, laughing, and remarking upon us in a language which seemed without backbone. Such rich brown men and women they were, with wavy, shining black hair, large, brown, lustrous eyes, and rows of perfect teeth like ivory. Everyone was smiling. The forms of the women seemed to be inclined towards obesity, but their drapery, which consists of a sleeved garment which falls in ample and unconfined folds from their shoulders to their feet, partly conceals this defect, which is here regarded as a beauty. Some of these dresses were black, but many of those worn by the younger women were of pure white, crimson, yellow, scarlet, blue, or light green. The men displayed their lithe, graceful figures to the best advantage in white trousers and gay Garibaldi shirts. A few of the women wore coloured handkerchiefs twined round their hair, but generally both men and women wore straw hats, which the men set jauntily on one side of their heads, and heightened their picturesqueness yet more by bandana handkerchiefs of rich, bright colours round their necks, knotted loosely on the left side, with a grace to which, I think, no Anglo-Saxon dandy could attain. Without an exception the men and women wore wreaths and garlands of flowers, carmine, orange, or pure white, twined round their hats, and thrown carelessly round their throats, flowers unknown to me, but redolent of the tropics in fragrance and colour. Many of the young beauties wore the gorgeous blossom of the red hibiscus among their abundant, unconfined, black hair, and many, besides the garlands, wore festoons of a sweet-scented vine, or of an exquisitely beautiful fern, knotted behind, and hanging halfway down their dresses. These adornments of natural flowers are most attractive. Chinamen, all alike, very yellow, with almond-shaped eyes, youthful, hairless faces, long pigtails, spotlessly clean clothes, and an expression of mingled cunning and simplicity, "foreigners," half-whites, a few negroes, and a very few dark-skinned Polynesians from the far-off South Seas, made up the rest of the rainbow-tinted crowd. The "foreign" ladies, who were there in great numbers, generally wore simple, light prints or muslins, and white straw hats, and many of them so far conformed to native custom as to wear natural flowers round their hats and throats. But where were the hard, angular, careworn, sallow, passionate faces of men and women, such as form the majority of every crowd at home, as well as in America and Australia? The conditions of life must surely be easier here, and people must have found rest from some of its burdensome conventionalities. The foreign ladies, in their simple, tasteful, fresh attire, innocent of the humpings and bunchings, the monstrosities and deformities of ultra-fashionable bad taste, beamed with cheerfulness, friendliness, and kindliness. Men and women looked as easy, contented, and happy as if care never came near them. I never saw such healthy, bright complexions as among the women, or such "sparkling smiles," or such a diffusion of feminine grace and graciousness anywhere. Outside this motley, genial, picturesque crowd about 200 saddled horses were standing, each with the Mexican saddle, with its lassoing horn in front, high peak behind, immense wooden stirrups, with great leathern guards, silver or brass bosses, and coloured saddle-cloths. The saddles were the only element of the picturesque that these Hawaiian steeds possessed. They were sorry, lean, undersized beasts, looking in general as if the emergencies of life left them little time for eating or sleeping. They stood calmly in the broiling sun, heavy-headed and heavyhearted, with flabby ears and pendulous lower lips, limp and rawboned, a doleful type of the " creation which groaneth and travaileth in misery." All these belonged to the natives, who are passionately fond of riding. Every now and then a flower-wreathed Hawaiian woman, in her full, radiant garment, sprang on one of these animals astride, and dashed along the road at full gallop, sitting on her horse as square and easy as a hussar. In the crowd and outside of it, and everywhere, there were piles of fruit for sale — oranges and guavas, strawberries, papayas, bananas (green and golden), cocoanuts, and other rich, fantastic productions of a prolific climate, where nature gives of her wealth the whole year round. Fishes, strange in shape and colour, crimson, blue, orange, rose, gold, such fishes as flash like living light through the coral groves of these enchanted seas, were there for sale, and coral divers were there with their treasures—branch coral, as white as snow, each perfect specimen weighing from eight to twenty pounds. But no one pushed his wares for sale—we were at liberty to look and admire, and pass on unmolested. No vexatious restrictions obstructed our landing. A sum of two dollars for the support of the Queen's Hospital is levied on each passenger, and the examination of ordinary luggage, if it exists, is a mere form. From the demeanour of the crowd it was at once apparent that the conditions of conquerors and conquered do not exist. On the contrary, many of the foreigners there were subjects of a Hawaiian king, a reversal of the ordinary relations between a white and a coloured race which it is not easy yet to appreciate. Two of my fellow-passengers, who were going on to San Francisco, were anxious that I should accompany them to the Pali, the great excursion from Honolulu; and leaving Mr. M to make all arrangements for the Dexters and myself, we hired a buggy, destitute of any peculiarity but a native driver, who spoke nothing but Hawaiian, and left the ship. This place is quite unique. It is said that 15,000 people are buried away in these low-browed, shadowy houses, under the glossy, dark-leaved trees, but except in one or two streets of miscellaneous, old-fashioned-looking stores, arranged with a distinct leaning towards native tastes, it looks like a large village, or rather like an aggregate of villages. As we drove through the town we could only see our immediate surroundings, but each had a new fascination. We drove along roads with over-arching trees, through whose dense leafage the noon sunshine only trickled in dancing, broken lights; umbrella trees, caoutchouc, bamboo, mango, orange, breadfruit, candlenut, monkey pod, date and coco palms, alligator pears, "prides" of Barbary, India, and Peru, and huge-leaved, wide-spreading trees, exotics from the South Seas, many of them rich in parasitic ferns, and others blazing with bright, fantastic blossoms. The air was heavy with odours of gardenia, tuberose, oleanders, roses, lilies, and the great white trumpet-flower, and myriads of others whose names I do not know, and verandahs were festooned with gorgeous magenta blossoms, passion-flowers, and a vine with masses of trumpet-shaped, yellow, waxy flowers. The delicate tamarind and the feathery algaroba intermingled their fragile grace with the dark, shiny foliage of the South Sea exotics, and the deep red, solitary flowers of the hibiscus rioted among familiar fuchsias and geraniums, which here attain the height and size of large rhododendrons. Few of the new trees surprised me more than the papaya. It is a perfect gem of tropical vegetation. It has a soft, indented stem, which runs up quite straight to a height of from 15 to 30 feet, and is crowned by a profusion of large, deeply indented leaves, with long foot-stalks, and among, as well as considerably below these, are the flowers or the fruit, in all stages of development. This, when ripe, is bright yellow, and the size of a musk melon. Clumps of bananas, the first sight of which, like that of the palm, constitutes a new experience, shaded the native houses with their wonderful leaves, broad and deep green, from five to ten feet long. The breadfruit is a superb tree, about 60 feet high, with deep green, shining leaves, a foot broad, sharply and symmetrically cut, worthy, from their exceeding beauty of form, to take the place of the acanthus in architectural ornament, and throwing their pale green fruit into delicate contrast. All these, with the exquisite rose apple, with a deep red tinere in its young leaves, the fan palm, the chirimoya, and numberless others, and the slender shafts of the coco palms rising high above them, with their waving plumes and perpetual fruitage, were a perfect festival of beauty. In the deep shade of this perennial greenery the people dwell. The foreign houses show a very various individuality. The peculiarity in which all seem to share is, that everything is decorated and festooned with flowering trailers. It is often difficult to tell what the architecture is, or what is house and what is vegetation; for all angles, lattices, balustrades, and verandahs are hidden by jessamine or passion-flowers, or the gorgeous, flame-like Bougainvillea. Many of the dwellings straggle over the ground without an upper story, and have very deep verandahs, through which I caught glimpses of cool, shady rooms, with matted floors. Some look as if they had been transported from the old-fashioned villages of the Connecticut Valley, with their clap-board fronts painted white, and jalousies painted green; but then the deep verandah in which families lead an open-air life has been added, and the chimneys have been omitted, and the New England severity and angularity are toned down and draped out of sight by these festoons of large-leaved, bright-blossomed, tropical climbing plants. Besides the frame houses there are houses built of blocks of a cream-coloured coral conglomerate laid in cement, of adobe, or large sun-baked bricks, plastered; houses of grass and bamboo: houses on the ground and houses raised on posts; but nothing looks prosaic, commonplace, or mean, for the glow and luxuriance of the tropics rest on all. Each house has a large garden or "yard," with lawns of bright perennial green, and banks of blazing, many-tinted flowers, and lines of Dracaena, and other foliage plants, with their great purple or crimson leaves, and clumps of marvellous lilies, gladiolas, ginger, and many plants unknown to me. Fences and walls are altogether buried by passion-flowers, the night-blowing Cereus, and the tropaeolum, mixed with geraniums, fuchsia, and jessamine, which cluster and entangle over them in indescribable profusion. A soft air moves through the upper branches, and the drip of water from miniature fountains falls musically on the perfumed air. This is mid-winter ! The summer, they say, is thermometrically hotter, but practically cooler, because of the regular trades which set in in April, but now, with the shaded thermometer at 8o° and the sky without clouds, the heat is not oppressive. The mixture of the neat grass houses of the natives with the more elaborate homes of the foreign residents has a very pleasant look. The "aborigines " have not been crowded out of sight, or into a special "quarter." We saw many groups of them sitting under the trees outside their houses, each group with a mat in the centre, with calabashes upon it containing poi, the national Hawaiian dish, a fermented paste made from the root of the kalo, or arum esculentum. As we emerged on the broad road which leads up the Nuuanu Valley to the mountains, we saw many patches of this kalo, a very handsome tropical plant, with large leaves of a bright tender green. Each plant was growing on a small hillock, with water round it. There were beautiful vegetable gardens also, in which Chinamen raise for sale not only melons, pineapples, sweet potatoes, and other edibles of hot climates, but the familiar fruits and vegetables of the temperate zones. In patches of surpassing neatness, there were strawberries, which are ripe here all the year, peas, carrots, turnips, asparagus, lettuce, and celery. I saw no other plants or trees which grow at home, but recognized as hardly less familiar growths the Victorian Eucalyptus, which has not had time to become gaunt and straggling, the Norfolk Island pine, which grows superbly here, and the handsome Moreton Bay fig. But the chief feature of this road is the number of residences; I had almost written of pretentious residences, but the term would be a base slander, as I have jumped to the conclusion that the twin vulgarities of ostentation and pretence have no place here. But certainly for a mile and a half or more there are many very comfortable-looking dwellings, very attractive to the eye, with an ease and imperturbable serenity of demeanour as if they had nothing to fear from heat, cold, wind, or criticism Their architecture is absolutely unostentatious, and their one beauty is that they are embowered among trailers, shadowed by superb exotics, and surrounded by banks of flowers, while the stately cocoanut, the banana, and the candlenut, the aborigines of Oahu, are nowhere displaced. One house with extensive grounds, a perfect wilderness of vegetation, was pointed out as the summer palace of Queen Emma, or Kaleeonalani, widow of Kamehameha IV., who visited England a few years ago, and the finest garden of all as that of a much respected Chinese merchant, named Afong. Oahu, at least on this leeward side, is not tropical looking, and all this tropical variety and luxuriance which delight the eye result from foreign enthusiasm and love of beauty and shade. When we ascended above the scattered dwellings and had passed the tasteful mausoleum, with two tall Kahilis, or feather plumes, at the door of the tomb in which the last of the Kamehamehas received Christian burial, the glossy, redundant, arborescent vegetation ceased. The kahili is shaped like an enormous bottle brush. The finest are sometimes twenty feet high, with handles twelve or fifteen feet long, covered with tortoiseshell and whale tooth ivory The upper part is formed of a cylinder of wicker work about a foot in diameter, on which red, black, and yellow feathers are fastened. These insignia are carried in procession instead of banners, and used to be fixed in the ground near the temporary residence of the king or chiefs. At the funeral of the late king seventy-six large and small kahilis were carried by the retainers of chief families. At that height a shower of rain falls on nearly every day in the year, and the result is a green sward which England can hardly rival, a perfect sea of verdure, darkened in the valley and more than half way up the hill sides by the foliage of the yellow-blossomed and almost impenetrable hibiscus, brightened here and there by the pea-green candlenut. Streamlets leap from crags and ripple along the roadside, every rock and stone is hidden by moist-looking ferns, as aerial and delicate as marabout feathers, and when the windings of the valley and the projecting spurs of mountains shut out all indications of Honolulu, in the cool, green loneliness one could imagine oneself in the temperate zones. The peculiarity of the scenery is, that the hills, which rise to a height of about 4,000 feet, are wall-like ridges of grey or coloured rock, rising precipitously out of the trees and grass, and that these walls are broken up into pinnacles and needles. At the Pali (wall-like precipice), the summit of the ascent of 1,000 feet, we left our buggy, and passing through a gash in the rock the celebrated view burst on us with overwhelming effect. Immense masses of black and ferruginous volcanic rock, hundreds of feet in nearly perpendicular height, formed the pali on either side, and the ridge extended northwards for many miles, presenting a lofty, abrupt mass of grey rock broken into fantastic pinnacles, which seemed to pierce the sky. A broad, umbrageous mass of green clothed the lower buttresses, and fringed itself away in clusters of coco palms on a garden-like stretch below, green with grass and sugar-cane, and dotted with white houses, each with its palm and banana grove, and varied by eminences which looked like long extinct tufa cones. Beyond this enchanted region stretched the coral reef, with its white, wavy line of endless surf, and the broad blue Pacific, ruffled by a breeze whose icy freshness chilled us where we stood. Narrow streaks on the landscape, every now and then disappearing behind intervening hills, indicated bridle tracks connected with a frightfully steep and rough zig-zag path cut out of the face of the cliff on our right. I could not go down this on foot without a sense of insecurity, but mounted natives driving loaded horses descended with perfect impunity into the dreamland below.

This pali is the scene of one of the historic tragedies of this island. Kamehameha the Conqueror, who after fierce fighting and much ruthless destruction of human life united the island sovereignties in his own person, routed the forces of the King of Oahu in the Nuuanu Valley, and drove them in hundreds up the precipice, from which they leaped in despair and madness, and their bones lie bleaching 800 feet below. The drive back here was delightful, from the wintry height, where I must confess that we shivered, to the slumbrous calm of an endless summer, the glorious tropical trees, the distant view of cool chasm-like valleys, with Honolulu sleeping in perpetual shade, and the still, blue ocean, without a single sail to disturb its profound solitude. Saturday afternoon is a gala-day here, and the broad road was so thronged with brilliant equestrians, that I thought we should be ridden over by the reckless rout. There were hundreds of native horsemen and horsewomen, many of them doubtless on the dejected quadrupeds I saw at the wharf, but a judicious application of long rowelled Mexican spurs, and a degree of emulation, caused these animals to tear along at full gallop. The women seemed perfectly at home in their gay, brass-bossed, high peaked saddles, flying along astride, bare-footed, with their orange and scarlet riding dresses streaming on each side beyond their horses' tails, a bright kaleidoscopic flash of bright eyes, white teeth, shining hair, garlands of flowers and many coloured dresses; while the men were hardly less gay, with fresh flowers round their jaunty hats, and the vermilion-coloured blossoms of the Ohia round their brown throats. Sometimes a troop of twenty of these free-and-easy female riders went by at a time, a graceful and exciting spectacle, with a running accompaniment of vociferation and laughter.

Among these we met several of the Nevada's officers, riding in the stiff, wooden style which Anglo-Saxons love, and a horde of jolly British sailors from H.M.S. Scout, rushing helter skelter, colliding with everybody, bestriding their horses as they would a top sailyard, hanging on to manes and lassoing horns, and enjoying themselves thoroughly. In the shady, tortuous streets we met hundreds more of native riders, dashing at full gallop without fear of the police. Many of the women were in flowing riding dresses of pure white, over which their unbound hair, and wreaths of carmine-tinted flowers fell most picturesquely. All this time I had not seen our domicile, and when our drive ended under the quivering shadow of large tamarind and algaroba trees, in front of a long, stone, two-storied house with two deep verandahs festooned with clematis and passion flowers, and a shady lawn in front, I felt as if in this fairy land anything might be expected. This is the perfection of an hotel. Hospitality seems to take possession of and appropriate one as soon as one enters its never-closed door, which is on the lower verandah. Everywhere, only pleasant objects meet the eye. One can sit all day on the back verandah, watching the play of light and colour on the mountains and the deep blue green of the Nuuanu Valley, where showers, sunshine, and rainbows make perpetual variety. The great dining-room is delicious. It has no curtains, and its decorations are cool and pale. Its windows look upon tropical trees in one direction, and up to the cool mountains in the other. Piles of bananas, guavas, limes, and oranges, decorate the tables at each meal, and strange vegetables, fish, and fruits vary the otherwise stereotyped American hotel fare. There are no female domestics. The host is a German, the manager an American, the steward a Hawaiian, and the servants are all Chinamen in spotless white linen, with pigtails coiled round their heads, and an air of superabundant good-nature. They know very little English, and make most absurd mistakes, but they are cordial, smiling, and obliging, and look cool and clean. The hotel seems the great public resort of Honolulu, the centre of stir—club-house, exchange, and drawing-room in one. Its wide corridors and verandahs are lively with English and American naval uniforms, several planters' families are here for the season; and with health-seekers from California, resident boarders, whaling captains, tourists from the British Pacific Colonies, and a stream of townspeople always percolating through the corridors and verandahs, it seems as lively and free-and-easy as a place can be, pervaded by the kindliness and bonhomie which form important items in my first impressions of the islands. The hotel was lately built by government at a cost of $120,000, a sum which forms a considerable part of that token of an advanced civilization, a National Debt. The minister whose scheme it was seems to be severely censured on account of it, but undoubtedly it brings strangers and their money into the kingdom, who would have avoided it had they been obliged as formerly to cast themselves on the hospitality of the residents. The present proprietor has it rent-free for a term of years, but I fear that it is not likely to prove a successful speculation either for him or the government. I dislike health resorts, and abhor this kind of life, but for those who like both, I cannot imagine a more fascinating residence. The charges are $15 a week, or $3 a day, but such a kindly, open-handed system prevails, that I am not conscious that I am paying anything! This sum includes hot and cold plunge baths ad libitum, justly regarded as a necessity in this climate. Dr. McGrew has hope that our invalid will rally in this healing, equable atmosphere. Our kind fellow-passengers are here, and take turns in watching and fanning him. Through the half-closed jalousies we see breadfruit trees, delicate tamarinds and algarobas, fan-palms, date-palms, and bananas, and the deep blue Pacific gleams here and there through the plumage of the cocoanut trees. A soft breeze, scented with a slight aromatic odour, wanders in at every opening, bringing with it, mellowed by distance, the hum and clatter of the busy cicada. The nights are glorious, and so absolutely still, that even the feathery foliage of the algaroba is at rest. The stars seem to hang among the trees like lamps, and the crescent moon gives more light than the full moon at home. The evening of the day we landed, parties of officers and ladies mounted at the door, and with much mirth disappeared on moonlight rides, and the white robes of flower-crowned girls gleamed among the trees, as groups of natives went by speaking a language which sounded more like the rippling of water than human speech. Soft music came from the ironclads in the harbour, and from the royal band at the king's palace, and a rich scent of dewy blossoms filled the delicious air. These are indeed the "isles of Eden," "the sun lands," musical with beauty. They seem to welcome us to their enchanted shores. Everything is new but nothing strange; for as I enjoyed the purple night, I remembered that I had seen such islands in dreams in the cold, gray North. " How sweet," I thought it would be, thus to hear far off, the low, sweet murmur of the "sparkling brine," to rest, and

A half-dream only, for one would not wish to be quite asleep and lose the consciousness of this delicious outer world. So I thought one moment. The next I heard a droning, humming sound, which certainly was not the surf upon the reef. It came nearer—there could be no mistake. I felt a stab, and found myself the centre of a swarm of droning, stabbing, malignant mosquitos. No, even this is not paradise! I am ashamed to say that on my first night in Honolulu I sought an early refuge from this intolerable infliction, in profound and prosaic sleep behind mosquito curtains. I. L. B. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |