The Hawaiian

Archipelago:

Six months amongst the

palm groves, coral reefs, and volcanoes of the Sandwich Islands

By Isabella L. Bird, 1875

LETTER 22

|

Koloa Woods — Bridal Rejoicings — Native Peculiarities— Missionary Matters—Risks attending an exclusively Native Ministry

Lihue, Kauai

I rode from Makaueli to Dr. Smith's, at Koloa, with two native attendants, a luna to sustain my dignity, and an inferior native to carry my carpet-bag. Horses are ridden with curb-bits here, and I had only brought a light snaffle, and my horse ran away with me again on the road, and when he stopped at last, these men rode alongside of me, mimicking me, throwing themselves back with their feet forwards, tugging at their bridles, and shrieking with laughter, exclaiming Maikai! Maikai! (good).

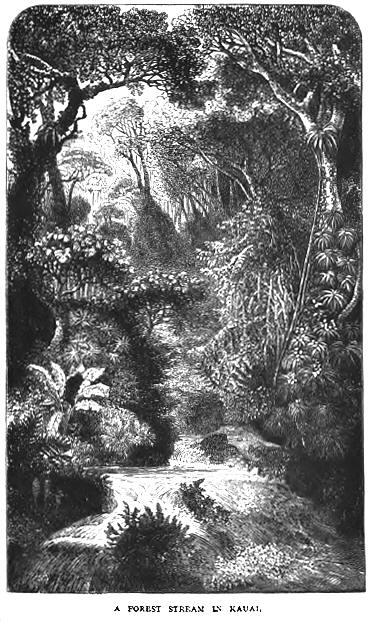

I remained several days at Koloa, and would gladly have accepted the hospitable invitation to stay as many weeks, but for a cowardly objection to "beating to windward" in the Jenny. One day, the girls asked me to go with them to the forests and return by moonlight, but they only spoke of them as the haunts of ferns, because they supposed that I should think nothing of them after the forests of Australia and New Zealand! They were not like the tropical woods of Hawaii, and owe more to the exceeding picturesqueness of the natural scenery. Hawaii is all domes and humps, Kauai all peaks and sierras. There were deep ravines, along which bright, fern-shrouded streams brawled among wild bananas, overarched by Eugenias, with their gory blossoms: walls of peaks, and broken precipices, grey ridges rising out of the blue forest gloom, high mountains with mists wreathing their spiky summits, for a background: gleams of a distant silver sea: and the nearer, many-tinted woods were not matted together in jungle fashion, but festooned and adorned with numberless lianas, and even the prostrate trunks of fallen trees took on new beauty from the exquisite ferns which covered them. Long cathedral aisles stretched away in far-off vistas, and so perfect at times was the Gothic illusion, that I found myself listening for anthems and the roll of organs. So cool and moist it was, and triumphantly redundant in vagaries of form and greenery, it was a forest of forests, and it became a necessity to return the next day, and the next; and I think if I had remained at Koloa I should have been returning still !

This place is outside the beauty, among cane-fields, and is much swept by the trade winds. Mr. Rice, my host, is the son of an esteemed missionary, and he and his wife take a deep interest in the natives. When he brought her here as a bride a few months ago, the natives were so delighted that he had married an island lady who could speak Hawaiian, that they gave them an ahaaina, or native feast, on a grand scale. The food was cooked in Polynesian style, by being wrapped up in greens called luau and baked underground. There were two bullocks, nineteen hogs, a hundred fowls, any quantity of poi and fruit, and innumerable native dishes. Five hundred natives, profusely decorated with leis of flowers and maile, were there, and each brought a gift for the bride. After the feast they chanted meles in praise of Mr. Rice, and Mrs. Rice played to them on her piano, an instrument which they had not seen before, and sang songs to them in Hawaiian. Mr. and Mrs. R. teach in and superintend a native Sunday-school, and have enlisted twenty native teachers, and in order to keep up the interest and promote cordial feeling, they and the other teachers meet once a month for a regular teachers' meeting, taking the houses in rotation. Refreshments are served afterwards, and they say that nothing can be more agreeable than the good feeling at the meetings, and the tact and graceful hospitality which prevail at the subsequent entertainments.

The Hawaiians are a most pleasant people to foreigners, but many of their ways are altogether aggravating. Unlike the Chinamen, they seldom do a thing right twice. In my experience, they have almost never saddled and bridled my horse quite correctly. Either a strap has been left unbuckled, or the blanket has been wrinkled under the saddle. They are too easy to care much about anything. If any serious loss arises to themselves or others through their carelessness, they shrug their shoulders, and say, "What does it matter?" Any trouble is just a pilikia. They can't help it. If they lose your horse from neglecting to tether it, they only laugh when they find you are wanting to proceed on your journey. Time, they think, is nothing to any one. "What's the use of being in a hurry?" Their neglect of their children, a cause from which a large proportion of the few that are born perish, is a part of this universal carelessness. The crime of infanticide, which formerly prevailed to a horrible extent, has long been extinct: but the love of pleasure and the dislike of trouble which partially actuated it, are apparently still stronger among the women than the maternal instinct, and they do not take the trouble necessary to rear their infants. They give their children away, too, to a great extent, and I have heard of instances in which children have been so passed from hand to hand, that they are quite ignorant of their real parents. It is an odd caprice in some cases, that women who have given away their own children are passionately attached to those whom they have received as presents, but I have nowhere seen such tenderness lavished upon infants as upon the pet dogs that the women carry about with them. Though they are so deficient in adhesiveness to family ties, that wives seek other husbands, and even children desert their parents for adoptive homes, the tie of race is intensely strong, and they are remarkably affectionate to each other, sharing with each other food, clothing, and all that they possess. There are no paupers among them but the lunatics and the lepers, and vagrancy is unknown. Happily on these sunny shores no man or woman can be tempted into sin by want

With all their faults, and their intolerable carelessness, all the foreigners like them, partly from the absolute security which they enjoy among them. They are so thoroughly good-natured, mirthful, and friendly, and so ready to enter heart and soul into all haole diversions, that the islands would be dreary indeed if the dwindling race became extinct. Among the many misfortunes of the islands, it has been a fortunate thing that the missionaries' families have turned out so well, and that there is no ground for the common reproach that good men's sons turn out reprobates.

The Americans show their usual practical sagacity in missionary matters. In 1853, when these islands were nominally Christianised, and a native ministry consisting of fifty-six pastors had been established, the American Board of Missions, which had expended during thirty-live years nine hundred and three thousand dollars in Christianising the group, and had sent out 149 male and female missionaries, resolved that it should not receive any further aid either in men or money.

In the early days, the King and chiefs had bestowed lands upon the Mission, on which substantial mission premises had been erected, and on withdrawing from the islands, the Board wisely made over these lands to the Mission families as freehold property. The result has been that, instead of a universal migration of the young people to America, numbers of them have been attached to Hawaiian soil. The establishment at an early date of Punahou College, at which for a small sum both boys and girls receive a first-class English education, also contributed to retain them on the islands, and numbers of the young men entered into sugar-growing, cattle-raising, storekeeping, and other businesses here. At Honolulu and Hilo a large proportion of the residents of the upper class are missionaries' children; most of the respectable foreigners on Kauai are either belonging to, or intimately connected with, the Mission families j and they are profusely scattered through Maui and Hawaii in various capacities, and are bound to each other by ties of extreme intimacy and friendliness, as well as by marriage and affinity. This "clan" has given society what it much wants—a sound moral core, and in spite of all disadvantageous influences, has successfully upheld a public opinion in favour of religion and virtue. The members of it possess the moral backbone of New England, and its solid good qualities, a thorough knowledge of the language and habits of the natives, a hereditary interest in them, a solid education, and in many cases much general culture.

In former letters I have mentioned Mr. Coan and Mr. Lyons as missionaries. I must correct this, as there have been no actual missionaries on the islands for twenty years. When the Board withdrew its support, many of the missionaries returned to America; some, especially among the secular members, went into other positions on the group, while the two first-mentioned and two or three besides, remained as pastors of native congregations.

I venture to think that the Board has been premature in transferring the islands to a native pastorate at such a very early stage of their Christianity. Such a pastorate must be too feeble to uphold a robust Christian standard of living. As an adjunct it would be essential to the stability of native Christianity, but it is not possible that it can be trusted as the sole depository of doctrine and discipline, and even were it all it ought to be, it would lack the power to repress the lax morality which is ruining the nation. Probably each year will render the over haste of this course more apparent, and it is likely that some other mode of upholding pure Christianity will have to be adopted, when the venerable men who now sustain and guide the native pastors by their influence shall have been gathered to their rest. I.L.B |

||

|

Letter 23: "Sundowning," An Evening Ride, The Vale of Hanalei, Exquisite Enjoyment and "Paniola" |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |