The Hawaiian

Archipelago:

Six months amongst the

palm groves, coral reefs, and volcanoes of the Sandwich Islands

By Isabella L. Bird, 1875

LETTER 29*

|

* I venture to present this journal letter just as it was written, trusting that the interest which attaches to volcanic regions, will carry the reader through the minuteness and multiplicity of the details.

A Second Visit to Kilauea—Remarkable Changes in Halemaumau—Terrible Aspects of the Pit—Theory and Aspects of the ”Blowing Cones”—A Shock of Earthquake—A Mountain Ranch

Crater House, Kilauea, June 4th

Once more I write with the splendours of the quenchless fires in sight, and the usual world seems twilight and commonplace by the fierce glare of Halemaumau, and the fitful glare of the other and loftier flame, which is burning ten thousand feet higher in lonely Mokua-weo-weo.

Mr. Green and I left Hilo soon after daylight this morning, and made about ”the worst time” ever made on the route. We jogged on slowly and silently for thirty miles in Indian file, through bursts of tropical beauty, over an ocean of fern-clad pahoehoe, the air hot and stagnant, the horses lazy and indifferent, till I was awoke from the kind of cautious doze into which one falls on a sure-footed horse, by a decided coolness in the atmosphere, and Kahele broke into a lumbering gallop, which he kept up till we reached this house, where, in spite of the exercise, we are glad to get close to a large wood fire. Although we are shivering, the mercury is at 57º, but in this warm and equable climate, one's sensations are not significant of the height of the thermometer.

It is very

fascinating to be here on the crater's edge, and to look across its

three miles of blackness to the clouds of red vapour which Halemaumau is

sending up, and altogether exciting to watch the lofty curve of Mauna

Loa upheave itself against the moon, while far and faint, we see, or

think we see, that solemn light, which ever since my landing at Kawaihae

has been so mysteriously attractive. It is three days off yet. Perhaps

its spasmodic fires will die out, and we shall find only blackness.

Perhaps anything, except our seeing it as it ought to be seen! The

practical difficulty about a guide increases, and Mr. Gilman cannot help

us to solve it. And if it be so cold at 4,000 feet, what will it be at

14,000? Kilauea, June 5th

I have no room in my thoughts for anything but volcanoes, and it will be so for some days to come. We have been all day in the crater, in fact I left Mr. Green and his native there, and came up with the guide, sore, stiff, bruised, cut, singed, grimy, with my thick gloves shrivelled off by the touch of sulphurous acid, and my boots nearly burned off. But what are cuts, bruises, fatigue, and singed eyelashes, in comparison with the awful sublimities I have witnessed to-day? The activity of Kilauea on Jan. 31 was as child's play to its activity today: as a display of fireworks compared to the conflagration of a metropolis. Then, the sense of awe gave way speedily to that of admiration of the dancing fire fountains of a fiery lake; now, it was all terror, horror, and sublimity, blackness, suffocating gases, scorching heat, crashings, surgings, detonations; half seen fires, hideous, tortured, wallowing waves. I feel as if the terrors of Kilauea would haunt me all my life, and be the Nemesis of weak and tired hours.

We left early, and descended the terminal wall, still, as before, green with ferns, ohias, and sandalwood, and bright with clusters of turquoise berries, and the red fruit and waxy blossom of the ohelo. The lowest depression of the crater, which I described before as a level, fissured sea of iridescent lava, has been apparently partially flooded by a recent overflow from Halemaumau, and the same agency has filled up the larger rifts with great shining rolls of black lava, obnoxiously like boa-constrictors in a state of repletion. In crossing this central area for the second time, with a mind less distracted by the novelty of the surroundings, I observed considerable deposits of remarkably impure sulphur, as well as sulphates of lime and alum in the larger fissures. The presence of moisture was always apparent in connection with these formations. The solidified surges and convolutions in which the lava lies, the latter sometimes so beautifully formed as to look like coils of wire rope, are truly wonderful. Within the cracks there are extraordinary coloured growths, orange, grey, buff, like mineral lichens, but very hard and brittle.

The recent lava flow by which Halemaumau has considerably heightened its walls, has raised the hill by which you ascend to the brink of the pit to a height of fully five hundred feet from the basin, and this elevation is at present much more fiery and precarious than the fonner one. It is dead, but not cold, lets one through into cracks hot with corrosive acid, rings hollow everywhere, and its steep acclivities lie in waves, streams, coils, twists, and tortuosities of all kinds, the surface glazed and smoothish, and with a metallic lustre.

Somehow, I expected to find Kilauea as I had left it in January, though the volumes of dense white smoke which are now rolling up from it might have indicated a change; but after the toilsome, breathless climbing of the awful lava hill, with the crust becoming more brittle, and the footing hotter at each step, instead of laughing fire fountains tossing themselves in gory splendour above the rim, there was a hot, sulphurous, mephitic chaos, covering, who knows what, of horror?

So far as we could judge, the level of the lake had sunk to about 80 feet below the margin, and the lately formed precipice was overhanging it considerably. About seven feet back from the edge of the ledge, there was a fissure about eighteen inches wide, emitting heavy fumes of sulphurous acid gas. Our visit seemed in vain, for on the risky verge of this crack we could only get momentary glimpses of wallowing fire, glaring lurid through dense masses of furious smoke which were rolling themselves round in the abyss as if driven by a hurricane.

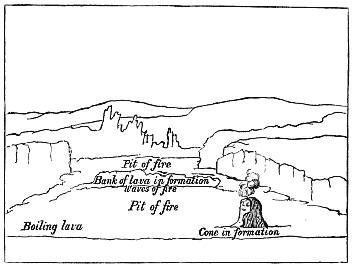

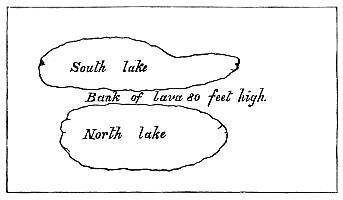

Outline of Halemaumau, June 4th

After failing to get a better standpoint, we suffered so much from the gases, that we coasted the north, till we reached the south lake, one with the other on my former visit, but now separated by a solid lava barrier about three hundred feet broad, and eighty high. Here there was comparatively little smoke, and the whole mass of contained lava was ebullient and incandescent, its level marked the whole way round by a shelf or rim of molten lava, which adhered to the side, as ice often adheres to the margin of rapids, when the rest of the water is liberated and in motion. There was very little centripetal action apparent. Though the mass was violently agitated it always took a southerly direction, and dashed itself with fearful violence against some lofty, undermined cliffs which formed its southern limit. The whole region vibrated with the shock of the fiery surges. To stand there was ”to snatch a fearful joy,” out of a pain and terror which were unendurable. For two or three minutes we kept going to the edge, seeing the spectacle as with a flash, through half closed eyes, and going back again; but a few trials, in which throats, nostrils, and eyes were irritated to torture by the acid gases, convinced us that it was unsafe to attempt to remain by the lake, as the pain and gasping for breath which followed each inhalation, threatened serious consequences.

With regard to the north lake we were more fortunate, and more persevering, and I regard the three hours we spent by it as containing some of the most solemn, as well as most fascinating, experiences of my life. The aspect of the volcano had altogether changed within four months. At present there are two lakes surrounded by precipices about eighty feet high. Owing to the smoke and confusion it is most difficult to estimate their size even approximately, but I think that the diameter of the two cannot be less than a fifth of a mile.

Within the pit or lake by which we spent the morning, there were no fiery mountains, or regular plashings of fiery waves playing in indescribable beauty in a faint, blue atmosphere, but lurid, gory, molten, raging, sulphurous, tormented masses of matter, half seen through masses as restless, of lurid smoke. Here, the violent action appeared centripetal, but with a southward tendency. Apparently, huge, bulging masses of a lurid-coloured lava were wallowing the whole time one over another in a central whirlpool, which occasionally flung up a wave of fire thirty or forty feet. The greatest intensity of action was always preceded by a dull, throbbing roar, as if the imprisoned gases were seeking the vent which was afforded them by the upward bulging of the wave and its bursting into spray. The colour of the lava which appeared to be thrown upwards from great depths, was more fiery and less gory than that nearer the surface. Now and then, through rifts in the smoke, we saw a convergence of the whole molten mass into the centre, which rose wallowing and convulsed to a considerable height. The awful sublimity of what we did see, was enhanced by the knowledge that it was only a thousandth part of what we did not see, mere momentary glimpses of a terror and fearfulness which otherwise could not have been borne.

A ledge, only three or four feet wide, hung over the lake, and between that and the comparative terra firma of the old lava, there was a fissure of unknown depth, emitting hot blasts of pernicious gases. The guide would not venture on the out side ledge, but Mr. Green, in his scientific zeal, crossed the crack, telling me not to follow him, but presently, in his absorption with what he saw, called to me to come, and I jumped across, and this remained our perilous standpoint.*

* Since then, the Austins of Onomea were standing on a similar ledge, when a sound as of a surge striking below, made them jump back hastily, and in another moment the projection split off and was engulfed in the fiery lake.

Burned, singed, stifled, blinded, only able to stand on one foot at a time, jumping back across the fissure every two or three minutes to escape an unendurable whiff of heat and sulphurous stench, or when splitting sounds below threatened the disruption of the ledge: lured as often back by the fascination of the horrors below; so we spent three hours.

There was every circumstance of awfulness to make the impression of the sight indelible. Sometimes, dense volumes of smoke hid everything, and yet, upwards, from out ”their sulphurous canopy” fearful sounds arose, crashings, thunderings, detonations, and we never knew then whether the spray of some uplifted wave might not dash up to where we stood. At other times the smoke partially lifting, but still swirling in strong eddies, revealed a central whirlpool of fire, wallowing at unknown depths, to which the lava, from all parts of the lake, slid centrewards and downwards as into a vortex, where it mingled its waves with indescribable noise and fury, and then, breaking upwards, dashed itself to a great height in fierce, gory gouts and clots, while hell itself seemed opening at our feet At times, again, bits of the lake skinned over with a skin of a wonderful silvery, satiny sheen, to be immediately devoured; and as the lurid billows broke, they were mingled with bright patches as if of misplaced moonlight. Always changing, always suggesting force which nothing could repel, agony indescribable, mystery inscrutable, terror unutterable, a thing of eternal dread, revealed only in glimpses!

It is natural to think that St. John the Evangelist, in some Patmos vision, was transported to the brink of this ”bottomless pit,” and found in its blackness and turbulence of agony the fittest emblems of those tortures of remorse and memory, which we may well believe are the quenchless flames of the region of self-chosen exile from goodness and from God. As natural, too, that all Scripture phrases which typify the place of woe should recur to one with the force of a new interpretation, ”Who can dwell with the everlasting burnings?” “The smoke of their torment goeth up for ever and ever,” “The place of hell,” “The bottomless pit,” “The vengeance of eternal fire,” “A lake of fire burning with brimstone.” No sight can be so fearful as this glimpse into the interior of the earth, where fires are for ever wallowing with purposeless force and aimless agony.

Beyond the lake there is a horrible region in which dense volumes of smoke proceed from the upper ground, with loud bellowings and detonations, and we took our perilous way in that direction, over very hot lava which gave way constantly. It is near this that the steady fires are situated which are visible from this house at night. We came first upon a solitary ”blowing cone,” beyond which there was a group of three or four, but it is not from these that the smoke proceeds, but from the extensive area beyond them, covered with smoke and steam cracks, and smoking banks, which are probably formed of sulphur deposits. I visited only the solitary cone, for the footing was so precarious, the sight so fearful, and the ebullitions of gases so dangerous, that I did not dare to go near the others, and do not wish ever to look upon their like again.

The one I saw was of beehive shape, about twelve feet high, hollow inside, and its walls were about two feet thick. A part of its imperfect top was blown off, and a piece of its side blown out, and the side rent gave one a frightful view of its interior, with the risk of having lava spat at one at intervals. The name ”Blowing Cone” is an apt one, if the theory of their construction be correct It is supposed that when the surface of the lava cools rapidly owing to enfeebled action below, the gases force their way upwards through small vents, which then serve as ”blow holes” for the imprisoned fluid beneath. This, rapidly cooling as it is ejected, forms a ring on the surface of the crust, which, growing upwards by accretion, forms a chimney, eventually nearly or quite closed at the top, so as to form a cone. In this case the cone is about eighty feet above the present level of the lake, and fully one hundred yards distant from its present verge.

The whole of the inside was red and molten, full of knobs, and great fiery stalactites. Jets of lava at a white heat were thrown up constantly, and frequently the rent in the side spat out lava in clots, which cooled rapidly, and looked like drops of bottle-green glass. The glimpses I got of the interior were necessarily brief and intermittent. The blast or roar which came up from below was more than deafening; it was stunning: and accompanied with heavy subterranean rumblings and detonations. The chimney, so far as I could see, opened out gradually down wards to a great width, and appeared to be. about forty feet deep; and at its base there was an abyss of lashing, tumbling, restless fire, emitting an ominous, surging sound, and breaking upwards with a fury which threatened to blow the cone and the crust on which it stands, into the air.

The heat was intense, and the stinging sulphurous gases, which were given forth in large quantities, most poisonous. The group of cones west of this one, was visited by Mr. Green; but he found it impossible to make any further explorations. He has seen nearly all the recent volcanic phenomena, but says that these cones present the most ”infernal” appearance he has ever witnessed. We returned for a last look at Halemaumau, but the smoke was so dense and the sulphur fumes so stifling, that, as in a fearful dream, we only heard the thunder of its hidden surges. I write thunder, and one speaks of the lashing of waves: but these are words pertaining to the familiar earth, and have no place in connection with Kilauea. The breaking lava has a voice all its own, full of compressed fury. Its sound, motion, and aspect are all infernal. Hellish, is the only fitting term.

We are dwelling on a cooled crust all over Southern Hawaii the whole region is recent lava, and between this and the sea there are several distinct lines of craters thirty miles long, all of which at some time or other have vomited forth the innumerable lava streams which streak the whole country in the districts of Kau, Puna, and Hilo. In fact, Hawaii is a great slag. There is something very solemn in the position of this crater-house: with smoke and steam coming out of every pore of the ground, and in front the huge crater, which to-night lights all the sky. My second visit has produced a far deeper impression even than the first, and one of awe and terror solely.

Kilauea is altogether different from the European volcanoes which send lava and stones into the air in fierce, sudden spasms, and then subside into harmlessness. Ever changing, never resting, the force which stirs it never weakening, raging for ever with tossing and strength like the ocean: its labours unfinished, and possibly never to be finished, its very unexpectedness adds to its sublimity and terror, for until you reach the terminal wall of the crater, it looks by daylight but a smoking pit in the midst of a dreary stretch of waste land.

Last night I thought the Southern Cross out of place; tonight it seems essential, as Calvary over against Sinai. For Halemaumau involuntarily typifies the necessity which shall consume all evil: and the constellation, pale against its lurid light, the great love and yearning of the Father, ”who spared not His own Son, but delivered Him up for us all,” that, ”as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive.”

Ainepo, Hawaii, June 5th

We had a great fright last evening. We had been engaging mules, and talking over our plans with our half-Indian host, when he opened the door and exclaimed, ”There's no light on Mauna Loa; the fires gone out.” We rushed out, and though the night was clear and frosty, the mountain curve rose against the sky without the accustomed wavering glow upon it. ”I'm afraid you'll have your trouble for nothing,” Mr. Gilman unsympathisingly remarked; ”anyhow, its awfully cold up there,” and rubbing his hands, reseated himself at the fire. Mr. G. and I stayed out till we were half frozen, and I persuaded myself and him that there was a redder tinge than the moonlight above the summit, but the mountain has given no sign all day, so that I fear that I ”evolved” he light out of my ”inner consciousness.”

Mr. Gilman was eloquent on the misfortunes of our predecessors, lent me a pair of woollen Socks to put on over my gloves, told me privately that if anyone could succeed in getting a guide it would be Mr. Green, and dispatched us at eight this morning with a lurking smile at our ”fool's errand,” thinly veiled by warm wishes for our success. Mr. Reid has two ranches on the mountain, seven miles distant from each other, and was expected every hour at the crater-house on his way to Hilo, but it was not known from which he was coming, and as it appeared that our last hope of getting a guide lay in securing his goodwill, Mr. G., his servant, and pack-mule took the lower trail, and I, with a native, a string of mules, and a pack-horse, the upper. Our plans for intercepting the good man were well laid and successful, but turned out resultless.

This has been an irresistibly comical day, and it is just as well to have something amusing interjected between the sublimities of Kilauea, and whatever to-morrow may bring forth. When our cavalcades separated, I followed the guide on a blind trail into the little-known regions on the skirts of Mauna Loa. We only travelled two miles an hour, and the mules kept getting up rows, kicking, and entangling their legs in the lariats, and one peculiarly malign animal dealt poor Kahele a gratuitous kick on his nose, making it bleed.

It is a strange, unique country, without any beauty. The seaward view is over a great stretch of apparent table-land, spotted with craters, and split by cracks emitting smoke or steam. The whole region is black with streams of spiked and jagged lava, meandering over it, with charred stumps of trees rising out of them.

The trail, if such it could be called, wound among koa and sandalwood trees occasionally, but habitually we picked our way over waves, coils, and hummocks of pahoehoe surrounded by volcanic sand, and with only a few tufts of grass, abortive ohelos, and vigorous sow-thistles (much relished by Kahele) growing in their crevices. Horrid cracks, 50 or 60 feet wide, probably made by earthquakes, abounded, and a black chasm of most infernal aspect dogged us on the left. It was all scrambling up and down. Sometimes there was long, ugly grass, a brownish green, coarse and tufty, for a mile or more. Sometimes clumps of wintry-looking, dead trees, sometimes clumps of attenuated living ones; but nothing to please the eye. We saw neither man nor beast the whole way, except a wild bull, which, tearing down the mountain side, crossed the trail just in front of us, causing a stampede among the mules, and it was fully an hour before they were all caught again.

The only other incident was an earthquake, the most severe, the men here tell me, that has been experienced for two years. One is prepared for any caprices on the part of the earth here, yet when there was a fearful internal throbbing and rumbling, and the trees and grass swayed rapidly, and great rocks and masses of soil were dislodged, and bounded down the hillside, and the earth reeled, and my poor horse staggered and stopped short, far from rising to the magnitude of the occasion, I thought I was attacked with vertigo, and grasped the horn of my saddle to save myself from falling. After a moment of profound stillness, there was again a subterranean sound like a train in a tunnel, and the earth reeled again with such violence, that I felt as if the horse and myself had gone over. Poor K. was nervous for some time afterwards. The motion was as violent as that of a large ship in a mid-Atlantic storm. There were four minor shocks within half an hour afterwards.

After crawling along for seven hours, and for the last two in a dripping fog, so dense that I had to keep within kicking range of the mules for fear of being lost, we heard the lowing of domestic cattle, and came to a place where felled trees, very difficult for the horses to cross, were lying. Then a rude boundary wall appeared, inside of which was a small, poor-looking grass house, consisting of one partially- divided room, with a small, ruinous-looking cook-house, a shed, and an unfinished frame-house near it. It looked, and is, a disconsolate conclusion of a wet day's ride. I rode into the corral, and found two or three very rough-looking whites and half-whites standing, and addressing one of them, I found he was Mr. Reid's manager there. I asked if they could give me a night's lodging, which seemed a diverting notion to them j and they said they could give me the rough accommodation they had, but it was hard even for them, till the new house was put up. They brought me into this very rough shelter, a draughty grass room, with a bench, table, and one chair in it, Two men came in, but not the native wife and family, and sat down to a calabash of pot and some strips of dried beef, food so coarse, that they apologised for not offering it to me. They said they had sent to the lower ranch for some flour, and in the meantime they gave me some milk in a broken bowl, their ”nearest approach to a tumbler,” they said. I was almost starving, for all our food was on the pack-mule. This is the place where we had been told that we could obtain tea, flour, beef, and fowls!

By some fatality my pen, ink, and knitting were on the pack mule; it was very cold, the afternoon fog closed us in, and darkness came on prematurely, so that 1 felt a most absurd sense of ennui, and went over to the cook-house, where I found Gandle cooking, and his native wife, with a heap of children and dogs lying round the stove. I joined them till my clothes were dry, on which the man, who, in spite of his rough exterior, was really friendly and hospitable, remarked that he saw I was ”one of the sort who knew how to take people as I found them.”

This regular afternoon mist which sets in at a certain altitude, blotting out the sun and sky, and bringing the horizon within a few yards, makes me certain after all that the mists of rainless Eden were a phenomenon, the loss of which is not to be regretted.

Still the afternoon hung on, and I went back to the house feeling that the most desirable event which the future could produce would be—a meal. Now and then the men came in and talked for a while, and as the darkness and cold intensified, they brought in an arrangement extemporised out of what looked like a battered tin bath, half full of earth, with some lighted faggots at the top, which gave out a little warmth and much stinging smoke. Actual, undoubted, night came on without Mr. Green, of whose failure I felt certain, and without food, and being blinded by the smoke, I rolled myself in a blanket and fell asleep on the bench, only to wake in a great fright, believing that the volcano house was burning over my head, and that a venerable missionary was taking advantage of the confusion to rob my saddle-bags, which in truth one of the men was moving out of harm's way, having piled up the fire two feet high.

Presently a number of voices outside shouted Haole! and Mr. Green came in shaking the water from his waterproof, with the welcome words, ”Everything's settled for to-morrow.” Mr. Reid threw cold water on the ascent, and could give no help; and Mr. G. being thus left to himself, after a great deal of trouble, has engaged as guide an active young goat-hunter, who, though he has never been to the top of the mountain, knows other parts of it so well that he is sure he can take us up. Mr. G. also brings an additional mule and pack-horse, so that our equipment is complete, except in the matter of cruppers, which we have been obliged to make for ourselves out of goats' hair rope and old stockings. If Mr. G. has an eye for the picturesque, he must have been gratified as he came in from the fog and darkness into the grass room, with the flaring fire in the middle, the rifles gleaming on the wall, the two men in very rough clothing, and myself huddled up in a blanket sitting on the floor, where my friend was very glad to join us.

Mr. Green has brought nothing but tea from Kapapala, but Gandle has made some excellent rolls, besides feasting us on stewed fowl, dough nuts, and milk! Little comfort is promised for to-night, as Gandle says, with a twinkle of kindly malice in his eye, that we shall not ”get a wink of sleep, for the place swarms with fleas.” They are a great pest of the colder regions of the islands, and, like all other nuisances, are said to have been imported! Gandle and the other man have entertained as with the misfortunes of our predecessors, on which they seem to gloat with ill-omened satisfaction. I.L.B

LETTER 29—continued—

Ascent of Mauna Loa—Pahoehoe and a-a—The Crater of Mokuaweoweo— The Great Fire-fountain—Our Camp—A Night Scene—An Alarming Ride

Kapapala, June 8th

The fleas at Ainepo quite fulfilled Mr. Gandle's prognostications, and I was glad when the stars went out one by one, and a red, cloudless dawn broke over the mountain, accompanied by a heavy dew and a morning mist, which soon rolled itself up into rosy folds and disappeared, and there was a legitimate excuse for getting up. Our host provided us with flour, sugar, and dough nuts, and a hot breakfast, and our expedition, comprising two natives who knew not a word of English, Mr. G. who does not know very much more Hawaiian than I do, and myself, started at seven. We had four superb mules, and two good pack-horses, a large tent, and a plentiful supply of camping blankets. I put on all my own warm clothes, as well as most of those which had been lent to me, which gave me the squat, padded look of a puffin or Esquimaux, but all and more were needed long before we reached the top. The mules were beyond all praise. They went up the most severe ascent I have ever seen, climbing steadily for nine hours, without a touch of the spur, and after twenty-four hours of cold, thirst, and hunger, came down again as actively as cats. The pack-horses too were very good, but from the comparative clumsiness with which they move their feet they were severely cut.

We went off, as usual, in single file, the guide first, and Mr. G. last The track was passably legible for some time, and wound through long grass and small koa trees, mixed with stunted ohias and a few common ferns. Half these koa trees are dead, and all, both living and dead, have their branches covered with a long hairy lichen, nearly white, making the dead forest in the slight mist look like a wood in England when covered with rime on a fine winter morning. The koa tree has a peculiarity of bearing two distinct species of leaves on the same twig, one like a curved willow leaf, the other that of an acacia.

After two hours' ascent we camped on the verge of the timber line, and fed our animals, while the two natives hewed firewood, and loaded the spare pack-horse with it. The sky was by that time cloudless, and the atmosphere brilliant, and both remained so until we reached the same place twenty-eight hours later, so that the weather favoured us in every respect, for there is ”weather" on the mountain, rains, fogs, and wind storms. The grass only grows sparsely in tufts above this place, and though vegetation exists up to a height of 10,000 feet on this side, it consists, for the most part, of grey lichens, a little withered grass, and a hardy asplenium.

At this spot the real business of the ascent begins, and we tightened our girths, distributed the baggage as fairly as possible, and made all secure before remounting.

We soon entered on vast uplands of pahoehoe which ground away the animals' feet, a horrid waste, extending upwards for 7,000 feet. For miles and miles, above and around, great billowy masses, tossed and twisted into an infinity of fantastic shapes, arrest and weary the eye, lava in all its forms, from a compact phonolite to the lightest pumice stone, the mere froth of the volcano. Recollect the vastness of this mountain. The whole south of this large island, down to and below the water's edge, is composed of its slopes. Its height is nearly three miles, and its base is 180 miles in circumference, so that Wales might be packed away within it, leaving room to spare. Yet its whole bulk, above a height of about 8,000 feet, is one frightful desert, at once the creation and the prey of the mightiest force on earth.

Struggling, slipping, tumbling, jumping, ledge after ledge was surmounted, but still, upheaved against the glittering sky, rose new difficulties to be overcome. Immense bubbles have risen from the confused masses, and bursting, have yawned apart. Swift-running streams of more recent lava have cleft straight furrows through the older congealed surface. Massive flows have fallen in, exposing caverned depths of jagged outlines. Earthquakes have riven the mountain, splitting its sides and opening deep crevasses, which must be leapt or circumvented. Horrid streams of a-a, which, after rushing remorselessly over the kindlier lava, have heaped rugged pinnacles of brown scoriae into impassable walls, have to be cautiously skirted. Winding round the bases of tossed up, fissured hummocks of pahoehoe, leaping from one broken hummock to another, clambering up acclivities so steep that the pack-horse rolled backwards once, and my cat-like mule fell twice, moving cautiously over crusts which rang hollow to the tread; stepping over deep cracks, which, perhaps, led down to the burning, fathomless sea, traversing hilly lakes ruptured by earthquakes, and split in cooling into a thousand fissures, painfully toiling up the sides of mounds of scoriae frothed with pumice-stone, and again for miles surmounting rolling surfaces of billowy. ropy lava—so passed the long day, under the tropic sun and the deep blue sky.

Towards afternoon, clouds heaped themselves in snowy masses, all radiance and beauty to us, all fog and gloom below, girdling the whole mountain, and interposing their glittering screen between us and the dark timber belt, the black, smoking shores of Kau, and the blue shimmer of the Pacific. From that time, for twenty-four hours, the lower world, and ”works and ways of busy men” were entirely shut out, and we were alone with this trackless and inanimate region of horror.

For the first time our guide hesitated as to the right track, for the faint suspicion of white smoke, which had kept alive our hope that the fire was still burning, had ceased to be visible. We called a halt while he reconnoitred, tried to eat some food, found that our pulses were beating 100 a minute, bathed our heads, specially our temples, with snow, as we had been advised to do by the oldest mountaineer on Hawaii, and heaped on yet more clothing. In fact, I tied a double woollen scarf over all my face but my eyes, and put on a French soldier's overcoat, with cape and hood, which Mr. Green had brought in case of emergency. The cold had become intense. We had not wasted words at any time, and on remounting, preserved as profound a silence as if we were on a forlorn hope, even the natives intermitting their ceaseless gabble.

Upwards still, in the cold bright air, coasting the edges of deep cracks, climbing endless terraces, the mules panting heavily, our breath coming as if from excoriated lungs,—so we surmounted the highest ledge. But on reaching the apparent summit we were to all appearance as far from the faint smoke as ever, for this magnificent dome, whose base is sixty miles in diameter, is crowned by a ghastly, volcanic table-land, creviced, riven, and ashy, twenty-four miles in circumference. A table-land, indeed, of dark grey lava, blotched by outbursts, and torn by streams of brown a-a, and full of hideous crevasses and fearful shapes, as if a hundred waves of lava had rolled themselves one on another, and had congealed in confused heaps.

Our guide took us a little wrong once, but soon recovered himself with much sagacity. ”Wrong” on Mauna Loa means being arrested by an impassable a-a stream, and our last predecessors had nearly been stopped by getting into one in which they suffered severely.

These a-a streams are very deep, and when in a state of fusion move along in a mass twenty feet high sometimes, with very solid walls. Professor Alexander, of Honolulu, supposes them to be from the beginning less fluid than pahoehoe, and that they advance very slowly, being full of solid points, or centres of cooling: that a-a, in fact, grains like sugar. Its hardness is indescribable. It is an aggregate of upright, rugged, adamantine points, and at a distance, a river of it looks like a dark brown Mer de Glace.

At half-past four we reached the edge of an a-a stream, about as wide as the Ouse at Huntingdon Bridge, and it was obvious that somehow or other we must cross it: indeed, I know not if it be possible to reach the crater without passing through one or another of these obstacles.* I should have liked to have left the animals there, but it was represented as impossible to proceed on foot, and though this was a decided misrepresentation, Mr. Green plunged in. I had resolved that he should never have any bother in consequence of his kindness in taking me with him, and, indeed, everyone had enough to do in taking care of himself and his own beast, but I never found it harder to repress a cry for help. Not that I was in the least danger, but there was every risk of the beautiful mule being much hurt, or breaking her legs. The fear shown by the animals was pathetic; they shrank back, cowered, trembled, breathed hard and heavily, and stumbled and plunged painfully. It was sickening to see their terror and suffering, the struggling and slipping into cracks, the blood and torture. The mules with their small legs and wonderful agility were more frightened than hurt, but the horses were splashed with blood up to their knees, and their poor eyes looked piteous.

* Professor George Forbes who ascended Mauna Loa in 1875, Informs me that he reached the crater without passing through a-a.

We were then, as we knew, close to the edge of the crater, but the faint smoke wreath had disappeared, and there was nothing but the westering sun hanging like a ball over the black horizon of the desolate summit. We rode as far as a deep fissure filled with frozen snow, with a ledge beyond, threw ourselves from our mules, jumped the fissure, and more than 800 feet below yawned the inaccessible blackness and horror of the crater of Mokuaweoweo, six miles in circumference, and 11,,000 feet long by 8,000 wide. The mystery was solved, for at one end of the crater, in a deep gorge of its own, above the level of the rest of the area, there was the lonely fire, the reflection of which, for six weeks, has been seen for too miles.

Nearly opposite us, a thing of beauty, a fountain of pure, yellow fire, unlike the gory gleam of Kilauea, was regularly playing in several united but independent jets, throwing up its glorious incandescence, to a height, as we afterwards ascertained, of from 150 to 300 feet, and attaining at one time 600! You cannot imagine such a beautiful sight. The sunset gold was not purer than the living fire. The distance which we were from it, divested it of the inevitable horrors which surround it. It was all beauty. For the last two miles of the ascent, we had heard a distant, vibrating roar: there, at the crater's edge, it was a glorious sound, the roar of an ocean at dispeace, mingled with the hollow murmur of surf echoing in sea caves, booming on, rising and falling, like the thunder music of windward Hawaii.

We sat on the ledge outside the fissure for some time, and Mr. Green actually proposed to pitch the tent there, but I dissuaded him, on the ground that an earthquake might send the whole thing tumbling into the crater; nor was this a whimsical objection, for during the night there were two such falls, and after breakfast, another quite near us.

We had travelled for two days under a strong impression that the fires had died out, so you can imagine the sort of stupor of satisfaction with which we feasted on the glorious certainty. Yes, it was glorious, that far-off fire-fountain, and the lurid cracks in the slow-moving, black-crusted flood, which passed calmly down from the higher level to the grand area of the crater.

This area, over two miles long, and a mile and a half wide, with precipitous sides 800 feet deep, and a broad second shelf about 300 feet below the one we occupied, at that time appeared a dark grey, tolerably level lake, with great black blotches, and yellow and white stains, the whole much fissured. No steam or smoke proceeded from any part of the level surface, and it had the unnaturally dead look which follows the action of fire. A ledge, or false beach, which must mark a once higher level of the lava, skirts the lake, at an elevation of thirty feet probably, and this fringed the area with various signs of present volcanic action, steaming sulphur banks, and heavy jets of smoke. The other side, above the crater, has a ridgy, broken look, giving the false impression of a mountainous region beyond. At this time the luminous fountain, and the red cracks in the river of lava which proceeded from it, were the only fires visible in the great area of blackness. In former days people have descended to the floor of the crater, but owing to the breaking away of the accessible part of the precipice, a descent is not feasible, though I doubt not that a man might even now get down, if he went up with suitable tackle, and sufficient assistance.

The one disappointment was that this extraordinary fire fountain was not only 800 feet below us, but nearly three quarters of a mile from us, and that it was impossible to get any nearer to it. Those who have made the ascent before have found themselves obliged either to camp on the very spot we occupied, or a little below it.

The natives pitched the tent as near to the crater as was safe, with one pole in a crack, and the other in the great fissure, which was filled to within three feet of the top with snow and ice. As the opening of the tent was on the crater side, we could not get in or out without going down into this crevasse. The tent walls were held down with stones to make it as snug as possible, but snug is a word of the lower earth, and has no meaning on that frozen mountain top. The natural floor was of rough slabs of lava, laid partly edgewise, so that a newly macadamised road would have been as soft a bed. The natives spread the horse blankets over it, and I arranged the camping blankets, made my own part of the tent as comfortable as possible by putting my inverted saddle down for a pillow, put on my last reserve of warm clothing, took the food out of the saddle bags, and then felt how impossible it was to exert myself in the rarefied air, or even to upbraid Mr. Green for having forgotten the tea, of which I had reminded him as often as was consistent with politeness!

This discovery was not made till after we had boiled the kettle, and ray dismay was softened by remembering that as water boils up there at 192º, our tea would have been worthless. In spite of my objection to stimulants, and in defiance of the law against giving liquor to natives, I made a great tin of brandy toddy, of which all partook, along with tinned salmon and dough-nuts. Then the men piled faggots on the fire and began their everlasting chatter, and Mr. Green and I, huddled up in blankets, sat on the outer ledge in solemn silence, to devote ourselves to the volcano.

The sun was just setting: the tooth-like peaks of Mauna Kea, cold and snow slashed, which were blushing red, the next minute turned ghastly against a chilly sky, and with the disappearance of the sun it became severely cold j yet we were able to remain there till 9.30, the first people to whom such a thing has been possible, so supremely favoured were we by the absence of wind.

When the sun had set, and the brief, red glow of the tropics had vanished, a new world came into being, and wonder after wonder flashed forth from the previously lifeless crater. Everywhere through its vast expanse appeared glints of fire—fires bright and steady, burning in rows like blast furnaces; fires lone and isolated, unwinking like planets, or twinkling like stars; rows of little fires marking the margin of the lowest level of the crater; fire molten in deep crevasses; fire in wavy lines; fire, calm, stationary, and restful: an incandescent lake two miles in length beneath a deceptive crust of darkness, and whose depth one dare not fathom even in thought. Broad in the glare, giving light enough to read by at a distance of three quarters of a mile, making the moon look as blue as an ordinary English sky, its golden gleam changed to a vivid rose colour, lighting up the whole of the vast precipices of that part of the crater with a rosy red, bringing out every detail here, throwing cliffs and heights into huge, black masses there, rising, falling, never intermitting, leaping in lofty jets with glorious shapes like wheat sheaves, coruscating, reddening, the most glorious thing beneath the moon was the fire-fountain of Mokuaweoweo.

By day the cooled crust of the lake had looked black and even sooty, with a fountain of molten gold playing upwards from it; by night it was all incandescent, with black blotches of cooled scum upon it, which were perpetually being devoured. The centre of the lake was at a white heat, and waves of white hot lava appeared to be wallowing there as in a whirlpool, and from this centre the fountain rose, solid at its base, which is estimated at 150 feet in diameter, but thinning and frittering as it rose into the air, and falling from the great altitude to which it attained, in fiery spray, which made a very distinct clatter on the fiery surface below. When one jet was about half high, another rose so as to keep up the action without intermission; and in the lower part of the fountain two subsidiary curved jets of great volume continually crossed each other. So, ”alone in its glory,” perennial, self-born, springing up in sparkling light, the fire-fountain played on as the hours went by.

From the nearer margin of this incandescent lake there was a mighty but deliberate overflow, a "silent tide” of fire, passing to the lower level, glowing under and amidst its crust, with the brightness of metal passing from a surface. In the bank of partially cooled and crusted lava which appears to support the lake, there were rifts showing the molten lava within. In one place heavy, white vapour blew off in powerful jets from the edge of the lake, and elsewhere there were frequent jets and ebullitions of the same, but there was not a trace of vapour over the burning lake itself. The crusted large area, with its blowing cones, blotches and rifts of fire, was nearly all visible, and from the thickness and quietness of the crust it was obvious that the ocean of lava below was comparatively at rest, but a dark precipice concealed a part of the glowing and highly agitated lake, adding another mystery to its sublimity.

It is probable that the whole interior of this huge dome is fluid, for the eruptions from this summit crater do not proceed from its filling up and running over, but from the mountain sides being unable to bear the enormous pressure; when they give way, high or low, and bursting, allow the fiery contents to escape. So, in 1855, the mountain side split open, and the lava gushed forth for thirteen months in a stream which ran for 60 miles, and flooded Hawaii for 300 square miles.*

* Since white men have inhabited the islands, there have been ten recorded eruptions from the craters of Mauna Loa, and one from Hualalai.

From the camping ground, immense cracks parallel with the crater, extend for some distance, and the whole of the compact grey stone of the summit is much fissured. These cracks, like the one by which our tent was pitched, contain water resting on ice. It shows the extreme difference of climate on the two sides of Hawaii, that while vegetation straggles up to a height of 10,000 feet on the windward side in a few miserable, blasted forms, it absolutely ceases at a height of 7,000 feet on the leeward.

It was too cold to sit up all night; so by the ”fire light” I wrote the enclosed note to you with fingers nearly freezing on the pen, and climbed into the tent.

It is possible that tent life in the East, or in the Rocky Mountains, with beds, tables, travelling knick-knacks of all descriptions, and servants who study their master's whims, may be very charming; but my experience of it having been of the make-shift and non-luxurious kind, is not delectable. A wooden saddle, without stuffing, made a very fair pillow; bu1 the ridges of the lava were severe. I could not spare enough blankets to soften them, and one particularly intractable point persisted in making itself felt. I crowded on everything attainable, two pairs of gloves, with Mr. Gilman's socks over them, and a thick plaid muffled up my face. Mr. Green and the natives, buried in blankets, occupied the other part of the tent. The phrase, ”sleeping on the brink of a volcano,” was literally true, for I fell asleep, and fear I might have been prosaic enough to sleep all night, had it not been for fleas which had come up in the camping blankets. When I woke, it was light enough to see that the three muffled figures were all asleep, instead of spending the night in shiverings and vertigo, as it appears that others have done. Doubtless the bathing of our heads several times with snow and ice-water had been beneficial.

Circumstances were singular. It was a strange thing to sleep on a lava-bed at a height of nearly 14,000 feet, far away from the nearest dwelling, ”in a region,” as Mr. Jarves says, ”rarely visited by man,” hearing all the time the roar, clash, and thunder of the mightiest volcano in the world. It seemed a wild dream, as that majestic sound moved on. There were two loud reports, followed by a prolonged crash, occasioned by parts of the crater walls giving way; vibrating rumblings, as if of earthquakes; and then a louder surging of the fiery ocean, and a series of most imposing detonations. Creeping over the sleeping forms, which never stirred even though I had to kneel upon one of the natives while I untied the flap of the tent, I crept cautiously into the crevasse in which the snow-water was then hard frozen, and out upon the projecting ledge. The four hours in which we had previously watched the volcano had passed like one; but the lonely hours which followed might have been two minutes or a year, for time was obliterated.

Coldly the Pole-star shivered above the frozen summit, and a blue moon, nearly full, withdrew her faded light into infinite space. The Southern Cross had set. Two peaks below the Pole-star, sharply defined against the sky, were the only signs of any other world than the world of fire and mystery around. It was light, broadly, vividly light; the sun himself, one would have thought, might look pale beside it. But such a light! The silver index of my thermometer, which had fallen to 23º Fahrenheit, was ruby red, that of the aneroid, which gave the height at 13,603 feet, was the same. The white duck of the tent was rosy, and all the crater walls and the dull-grey ridges which lie around were a vivid rose red.

All Hawaii was sleeping. Our Hilo friends looked out the last thing; saw the glare, and probably wondered how we were ”getting on,” high up among the stars. Mine were the only mortal eyes which saw what is perhaps the grandest spectacle on earth. Once or twice I felt so overwhelmed by the very sublimity of the loneliness, that I turned to the six animals, which stood shivering in the north wind, without any consciousness than that of cold, hunger, and thirst. It was some relief even to pity them, for pity was at least a human feeling, and a momentary rest from the thrill of the new sensations inspired by the circumstances. The moon herself looked a wan, unfamiliar thing—not the same moon which floods the palm and mango groves of Hilo with light and tenderness. And those palm and mango groves, and lighted homes, and seas, and ships, and cities, and faces of friends, and all familiar things, and the day before, and the years before, were as things in dreams, coming up out of a vanished past. And would there ever be another day, and would the earth ever be young and green again, and would men buy and sell and strive for gold, and should I ever with a human voice tell living human beings of the things of this midnight? How far it was from all the world, uplifted above love, hate, and storms of passion, and war, and wreck of thrones, and dissonant clash of human thought, serene in the eternal solitudes!

Things had changed, as they change hourly in craters. The previous loud detonations were probably connected with the evolutions of some ”blowing cones,” which were now very fierce, and throwing up lava at the comparatively dead end of the crater. Lone stars of fire broke out frequently through the blackened crust. The molten river, flowing from the incandescent lake, had advanced and broadened considerably. That lake itself, whose diameter has been estimated at 800 feet, was rose-red and self-illuminated, and the increased noise was owing to the increased force of the fire-fountain, which was playing regularly at a height of 300 feet, with the cross fountains, like wheat-sheaves, at its lower part. These cross fountains were the colour of a mixture of blood and fire, and the lower part of the perpendicular jets was the same; but as they rose and thinned, this colour passed into a vivid rose red, and the spray and splashes were as rubies and flame mingled. For ever falling in fiery masses and fiery foam: accompanied by a thunder-music of its own: companioned only by the solemn stars: exhibiting no other token of its glories to man than the reflection of its fires on mist and smoke; it burns for the Creator's eye alone, for no foot of mortal can approach it.

Hours passed as I watched the indescribable glories of the fire-fountain, its beauty of form, and its radiant reflection on the precipices, 800 feet high, which wall it in, and listened to its surges beating, and the ebb and flow of its thunder music. Then a change occurred. The jets, which for long had been playing at a height of 300 feet, suddenly became quite low, and for a few seconds appeared as cones of fire wallowing in a sea of light; then with a roar like the sound of gathering waters, nearly the whole surface of the lake was lifted up by the action of some powerful internal force, and its whole radiant mass, rose three times, in one glorious, upward burst, to a height, as estimated by the surrounding cliffs, of 600 feet, while the earth trembled, and the moon and stars withdrew abashed into far-off space. After this the fire fountain played as before. The cold had become intense, 11° of frost; and I crept back into the tent: those words occurring to me with a new meaning, ”dwelling in the light which no man can approach unto.”

We remained in the tent till the sun had slightly warmed the air, and then attempted to prepare breakfast by the fire; but no one could eat anything, and the native from Waimea complained of severe headache, which shortly became agonizing, and he lay on the ground moaning, and completely prostrated by mountain sickness. I felt extreme lassitude, and exhaustion followed the slightest effort; but the use of snow to the head produced great relief. The water in our canteens was hard frozen, and the keenness of the cold aggravated the uncomfortable symptoms which accompany pulses at no°. The native guide was the only person capable of work, so we were late in getting off, and rode four and a half hours to the camping ground, only stopping once to tighten our girths. Not a rope, strap, buckle, or any of our gear gave way, and though I rode without a crupper, the breeching of a pack mule's saddle kept mine steady.

The descent, to the riders, is far more trying than the ascent, owing to the continued stretch of very steep declivity for 8,000 feet; but our mules never tripped, and came into Ainepo as if they had not travelled at all. The horses were terribly cut, both again in the a-a stream, and on the descent. It was sickening to follow them, for at first they left fragment* of hide and hair on the rocks, then flesh, and when there was no more hide or flesh to come off their poor heels and fetlocks, blood dripped on every rock, and if they stood still for a few moments, every hoof left a little puddle of gore. We had all the enjoyment and they all the misery. I was much exhausted when we reached the camping-ground, but soon revived under the influence of food; but the poor native, who was really very ill, abandoned himself to wretchedness, and has only recovered to-day.

The belt of cloud which was all radiance above, was all drizzling fog below, and we reached Ainepo in a regular Scotch mist. The ranchmen seemed rather grumpy at our successful ascent, which involved the failure of all their prophecies, and, indeed, we were thoroughly unsatisfactory travellers, arriving fresh and complacent, with neither adventures nor disasters to gladden people's hearts. We started for this ranch seven miles further, soon after dark, and arrived before nine, after the most successful ascent of Mauna Loa ever made.

Without being a Sybarite, I certainly do prefer a comfortable pulu bed to one of ridgy lava, and the fire which blazes on this broad hearth to the camp-fire on the frozen top of the volcano, The worthy ranchman expected us, and has treated us very sumptuously, and even Kahele is being regaled on Chinese sorghum. The Sunday's rest, too, is a luxury, which I wonder that travellers can ever forego. If one is always on the move, even very vivid impressions are hunted out of the memory by the last new thing. Though I am not unduly tired, even had it not been Sunday, I should have liked a day in which to recall and arrange my memories of Mauna Loa before the forty-eight miles' ride to Hilo.

This afternoon, we were sitting under the verandah talking volcanic talk, when there was a loud rumbling, and a smart shock of earthquake, and I have been twice interrupted in writing this letter by other shocks, in which all the frame-work of the house has yawned and closed again. They say that four years ago, at the time of the great ”mud flow” which is close by, this house was moved several feet by an earthquake, and that all the cattle walls which surround it were thrown down. The ranchman tells us that on January 7th and 8th, 1873, there was a sudden and tremendous outburst of Mauna Loa. The ground, he says, throbbed and quivered for twenty miles; a tremendous roaring, like that of a blast furnace, was heard for the same distance, and clouds of black smoke trailed out over the sea for thirty miles.

We have dismissed our guide with encomiums. His charge was $10; but Mr. Green would not allow me to share that, or any part of the expense, or pay anything, but $6 for my own mule. The guide is a goat-hunter, and the chase is very curiously pursued. The hunter catches sight of a flock of goats, and hunts them up the mountain, till, agile and fleet of foot as they are, he actually tires them out, and gets close enough to them to cut their throats for the sake of their skins. If I understand rightly, this young man has captured as many as seventy in a day.

Crater House, Kilauea, June 9th

This morning Mr. Green left for Kona, and I for Kilauea; the ranchman's native wife and her sister riding with me for several miles to put me on the right track. Kahele's sociable Instincts are so strong, that, before they left me, I dismounted, blindfolded him, and led him round and round several times, a process which so successfully confused his intellects, that he started off in this direction with more alacrity than usual. They certainly put me on a track which could not be mistaken, for it was a narrow, straight path, cut and hammered through a broad, horrible a-a stream, whose jagged spikes were the height of the horse. But beyond this lie ten miles of pahoehoe, the lava-flows of ages, with only now and then the vestige of a trail.

Except the perilous crossing of the Hilo gulches in February, this is the most difficult ride I have had—eerie and impressive in every way. The loneliness was absolute. For several hours I saw no trace of human beings, except the very rare print of a shod horse's hoof. It is a region for ever ”desolate and without inhabitant,” trackless, waterless, silent, as if it had passed into the passionless calm of lunar solitudes. It is composed of rough hummocks of pahoehoe, rising out of a sandy desert. Only stunted ohias, loaded with crimson tufts, raise themselves out of cracks: twisted, tortured growths, bearing their bright blossoms under protest, driven unwillingly to be gay by a fiery soil and a fiery sun. To the left, there was the high, dark wall of an a-a stream; further yet, a tremendous volcanic fissure, at times the bed of a fiery river, and above this the towering dome of Mauna Loa, a brilliant cobalt blue, lined and shaded with indigo where innumerable lava streams have seamed his portentous sides: his whole beauty the effect of atmosphere, on an object in itself hideous. Ahead and to the right were rolling miles of a pahoehoe sea, bounded by the unseen Pacific 3,000 feet below, with countless craters, fissures emitting vapour, and all other concomitants of volcanic action; bounded to the north by the vast crater of Kilauea. On all this deadly region the sun poured his tropic light and heat from one of the bluest skies I ever saw.

The direction given me on leaving Kapapala was, that after the natives left me I was to keep a certain crater on the south-east till I saw the smoke of Kilauea; but there were many craters. Horses cross the sand and hummocks as nearly as possible on a bee line; but the lava rarely indicates that anything has passed over it, and this morning a strong breeze had rippled the sand, completely obliterating the hoof-marks of the last traveller, and at times I feared that losing myself, as many others have done, I should go mad with thirst. I examined the sand narrowly for hoof-marks, and every now and then found one, but always had the disappointment of finding that it was made by an unshod horse, therefore not a ridden one. Finding eyesight useless, I dismounted often, and felt with my finger along the rolling lava for the slightest marks of abrasion, which might show that shod animals had passed that way, got up into an ohia to look out for the smoke of Kilauea, and after three hours came out upon what I here learn is the old track, disused because of the insecurity of the ground.

It runs quite close to the edge of the crater, there 1,000 feet in depth, and gives a magnificent view of the whole area, with the pit and the blowing cones. But the region through which the trail led was rather an alarming one, being hollow and porous, all cracks and fissures, nefariously concealed by scrub and ferns. I found a place, as I thought, free from risk, and gave Kahele a feed of oats on my plaid, but before he had finished them there was a rumbling and vibration, and he went into the ground above his knees, so snatching up the plaid and jumping on him I galloped away, convinced that that crack was following me! However, either the crack thought better of it, or Kahele travelled faster, for in another half-hour I arrived where the whole region steams, smokes, and fumes with sulphur, and was kindly welcomed here by Mr. Gilman, where he and the old Chinaman appear to be alone.

After a seven hours' ride the quiet and the log fire are very pleasant, and the host is a most intelligent and sympathising listener. It is a solemn night, for the earth quakes, and the sound of Halemaumau is like the surging of the sea.

Hilo, June 11th

Once more I am among palm and mango groves, and friendly faces, and sounds of softer surges than those of Kilauea. I had a dreary ride yesterday, as the rain was incessant, and I saw neither man, bird, or beast the whole way. Kahele was so heavily loaded that I rode the thirty miles at a foot's pace, and he became so tired that I had to walk.

It has been a splendid week, with every circumstance favourable, nothing sordid or worrying to disturb the impressions received, kindness and goodwill everywhere, a travelling companion whose consideration, endurance, and calmness were beyond all praise, and at the end the cordial welcomes of my Hawaiian ”home." I.L.B |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |