A

Cultural History of Three

Traditional Hawaiian Sites

on the

West Coast of Hawai'i Island

Overview of Hawaiian History

by Diane Lee Rhodes

(with some additions by Linda Wedel Greene)

|

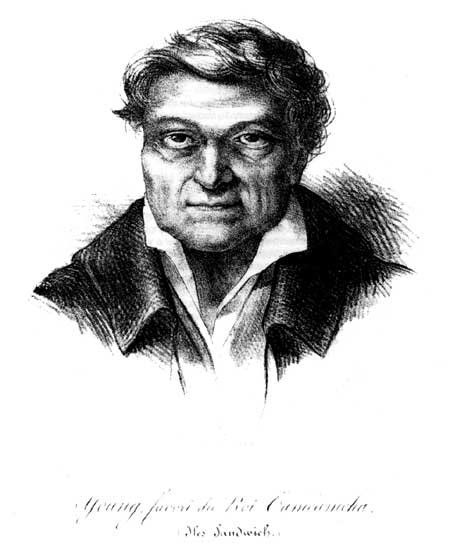

Chapter 3: Foreign Population Grows A. First White Residents of Hawai'i 1. Kamehameha Detains Two Foreigners The first known westerners to have remained in the Hawaiian Islands, and certainly among the most influential individuals in terms of their impact on Hawaii's development, were an Englishman, John Young, and a Welshman, Isaac Davis. Both men were detained in Hawai'i unwillingly as the result of rather strange and interrelated circumstances. As mentioned, during the 1790s an increasing volume of trade had evolved between Hawaiian chiefs offering food, firewood, and fresh water, and foreign sea captains pedaling cargoes of metal, firearms, gunpowder, and cloth. The Hawaiian ali'i avidly desired such foreign goods, for through them they gained status and power over their rivals. Isaac Davis served as mate on a small schooner, the Fair American, commanded by Thomas Metcalf, the son of Captain Simon Metcalf of the American snow Eleanor out of New York. Both vessels were bound on a northwest fur-trading voyage, which included a rendezvous in the Hawaiian Islands if they became separated. Reaching the islands, the elder Metcalf traded off the coast of Hawai'i during the winter of 1789, ultimately moving over to Maui. Metcalf was, by all accounts, an irascible, harsh individual, who believed in strong and immediate punishment for infractions of his rules. When natives stole a small boat he was towing and killed its watchman, he sought a secret, murderous revenge. Sailing to the village of the suspected thieves, he waited until the trusting inhabitants had gathered in their canoes around his ship, eager for trade, and then opened fire, indiscriminately killing more than 100 natives and wounding several hundred more. Avenged of his losses, Metcalf weighed anchor and returned to the island of Hawai'i where he initiated a seemingly friendly intercourse with the natives at Kealakekua Bay. Kame'eiamoku, one of the North Kona chiefs on Hawai'i, however, had previously been insulted by Metcalf and vowed revenge on the next ship that passed his way. By coincidence, it happened to be the Fair American, seeking land near Kawaihae Bay. The opportunity to avenge his insult by foreigners, the defenseless state of the vessel due to its small crew and inexperienced commander, and the value of the muskets and other iron implements on board sealed the vessel's doom. Metcalf and his crew were either killed or drowned. The only survivor was Isaac Davis, who, although wounded, jumped overboard and managed to reach a native canoe, whose occupant clubbed him into submission but for some reason spared his life. The Fair American was hauled ashore and Kamehameha later appropriated it, its guns, ammunition, and other articles of trade, as well as Davis himself. During this event, the Eleanor remained anchored at Kealakekua. John Young, a native of Liverpool, England (Illustration 20), serving as boatswain, went on shore one day with some of his shipmates to see the country, and, venturing far inland, returned alone to the beach too late to reboard the vessel. In addition, he discovered that Kamehameha had instituted a kapu on all canoes and was prohibiting the population from further contact with the Eleanor. A combination of reasons probably influenced that action. First, having just been informed of the capture of the Fair American, Kamehameha undoubtedly feared retribution from Captain Metcalf. Second, Kamehameha was still involved in warfare both with other chiefs on Hawai'i and with the rulers of the other islands. Because he was slowly amassing a quantity of arms and ammunition to combat these threats, he may have felt in dire need of knowledgeable foreigners with the expertise to handle those items, care for and repair them, and train his warriors in their use.

Puzzled by the sudden lack of activity in the bay, the crew of the Eleanor remained offshore for two days, firing guns and awaiting Young's return. Finally, puzzled by the sudden disruption of trading, frustrated by his broken contact with the Fair American, and probably thinking Young had deserted, Metcalf set sail for China. These events mark a turning point in Hawaiian history, for they provide the catalysts, in the form of Young and Davis, that enabled Kamehameha to succeed in his military ventures and eventually assert his dominance in the islands. It is the beginning of the transformation of the ancient Hawaiian civilization to a modern state. 2. Young and Davis Adjust to Their New Life Although at first full of despair and fearful of what lay ahead, the two white men received only kind and respectful treatment from Kamehameha and his people:

Young later told Vancouver's party that, having been present at Kealakekua with Kamehameha at the time he received the news of the seizure of the Fair American, he could vouch for the fact that the king was very disturbed over the incident. Archibald Menzies, Hawaii Nei 128 Years Ago (Honolulu: New Freedom Press, 1920), p. 97. Because Kamehameha wished to encourage friendly relations with visiting ships, he must have been greatly angered at Kame'eiamoku's actions and fearful of how they might affect future relations with foreign powers. Menzies, ibid., p. 96, states that King Kamehameha was anxious that Young and Davis remain on the island until Metcalf returned so that they could tell him that the king had played no part in the seizure of the Fair American. According to Captain Joseph Ingraham, the natives at Kaleakekua were planning to attack the Eleanor, but were dissuaded at the last minute. Fearing further trouble, the king sent Metcalf a letter telling him to depart immediately or risk losing his vessel. "Log of the Brig Hope called the Hope's Track Among the Sandwich Islands, May 20-Oct. 12, 1791," Hawaiian Historical Society Reprint #3 (Honolulu: Paradise of the Pacific Press; 1918), pp. 16-17, photographed from the original in the Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Finding their lives secure, and being watched closely and unable to escape, Young and Davis became reconciled to their lot. Their fortunes became quickly and closely linked to those of the king. They would play a significant role in Kamehameha's rise to dominance, and Young, especially, who quickly gained the king's trust and became his principal advisor, would be visited, consulted, or at least mentioned by every visitor to the islands for the next forty years. Young and Davis, although untutored seamen, were far above the ordinary class of sailor to which the Hawaiians had become accustomed. Possibly because they realized that in their position as advisor to Kamehameha they could accomplish things for themselves that would have been impossible elsewhere, they rose to the occasion and displayed great intelligence and fairness in their dealings with Kamehameha as well as sincere compassion for the Hawaiian people. By the time Vancouver reached the islands on his 1793 voyage, Young and Davis had been residing there for three years. Vancouver wrote at this time that Young and Davis "are in his [Kamehameha's] most perfect confidence, attend him in all his excursions of business or pleasure, or expeditions of war or enterprise; and are in the habit of daily experiencing from him the greatest respect, and the highest degree of esteem and regard." The two men were

Young stated about two years after Davis's death that after Davis recovered from his wounds, neither of them had any particular reason to complain of the treatment they received from the natives. He said "We rendered great and important services to the king in his wars, and, in consequence, were held in high estimation by his majesty, and the principal and subordinate chiefs and warriors." Young admits, however, that

Vancouver left a letter with Young and Davis in 1793 commending them to visiting sea captains as men who could be trusted and requesting that they be treated with civility and hospitality by any subjects of Great Britain and those of other powers dealing with them. At the same time, he enjoined Young and Davis to render every service they could to Europeans and Americans who visited the island while they were there. Young and Davis owed much to Vancouver. Artemas Bishop wrote in 1826 that Young had told him that, after the Eleanor set sail, he and Davis had "wandered from place to place dressed in the native habit, until at the suggestion of Capt. Vancouver, Tamehameha gave them land." The following year Vancouver stated that he felt that Young and Davis's presence, conduct, and good advice to the king and chiefs had been "materially instrumental in causing the honest, civil and attentive behavior lately experienced by all visitors from the inhabitants of this island." 3. Young and Davis Aid Kamehameha's Wars of Conquest Vancouver heartily encouraged Kamehameha and the Kona-Kohala chiefs to take advantage of the political expertise, technical knowledge, and military skills of Young and Davis in their struggle for dominance. In fact the success in conquest these chiefs experienced was primarily due to Young's and Davis's knowledge of Western firearms — including cannon and rifles, of fortification techniques, and of the martial arts." Kamehameha had a rather interesting method of utilizing his foreigners in battle:

Although other chiefs also employed foreign military experts, Kamehameha used his most successfully. Militarily Young and Davis were indispensable to Kamehameha during his conquest period, from about 1790 through the capitulation of Kaua'i in 1810. During this time they adopted the use of gunpowder and European military tactics to Hawaiian warfare. They mounted the small cannon from the Fair American on carriages and trained the king's troops in the use of muskets and other firearms. It was a swivel gun obtained from a trader and mounted on a large double Canoe, manned by Young and Davis, that gave Kamehameha his advantage in naval warfare. The two advisors were also instrumental in providing Kamehameha's navy with the first keeled vessel constructed in Hawai'i, with the help of Captain Vancouver's carpenters. They also helped the king fortify his kingdom against invasion by building forts. Young and Davis, in charge of artillery, were especially important in engagements at Hilo against the forces of Keoua, in the naval encounter off Waipio under Ke'eaumoku, in the conquest of Maui, and in the celebrated battle of Nu'uanu that won O'ahu. 4. Young and Davis Conduct Business with Foreign Traders In the years following Cook's discovery of Hawai'i, Kamehameha began to realize the advantages of having loyal white men within his inner circle to deal with foreign traders. Over this period of time he had become cognizant of the broad business acumen and wide variety of skills that foreigners possessed and had come to understand the need of including in his retinue foreign advisors adept in diplomacy and navigational and technical matters as well as military strategy. Young and Davis, in addition to being the king's business agents, acted as interpreters between the king and foreign traders, supplying information to the former on the customs and habits of the visitors and explaining the Hawaiian way of thinking to the latter. When explorer Otto von Kotzebue wanted to survey Honolulu harbor, his men erected poles around the perimeter of the water to which white flags were attached. These greatly upset the Hawaiians, who believed either the Russians were taking possession of the island or that foreigners were making the waters kapu. Young explained the local agitation to Kotzebue, who then substituted brooms for the flying flags. Known to Hawaiians as "Olohana," in reference to his frequent boatswain's call of "All Hands" for any duty he required of them, Young piloted many ships in and out of Hawaiian harbors and served as Kamehameha's agent in business transactions with visiting sea captains. On board ship Young would provide the visitors with information about activities on the island and the arrival and departure times of other trading vessels and dispense any current news that might interest them. Archibald Menzies, surgeon and naturalist with Vancouver on board the Discovery, states that Young and Davis were extremely useful to them because of their acquired knowledge of the language and customs of the Hawaiians:

William Shaler, master of the Lelia Byrd, which brought the first horses to Hawai'i in 1803, said that

Georg von Langsdorff noted in 1805 that

5. Young and Davis Settle Permanently into Hawaiian Life Before long, Young and Davis had made a secure niche for themselves in Hawaiian society. John Boit, master of the Union, in the Sandwich Islands in 1795, said that he had

The high regard in which the king held these men was evidenced by the recollection of Ebenezer Townsend, of the Neptune, who noted in 1798 after a meeting with the king on board his ship before sailing that

Townsend also noticed that

Not that friction did not sometimes develop between the king and his foreign advisors. John Papa I'i mentions:

An anecdote relates how Young obtained a high level of power and influence. It is said his popularity with the king created some animosity with the priesthood. A certain kahuna let it be known he planned to kill Young and had already retreated to the woods to build a hut in which to pray him to death. Young then proceeded to build a small, round hut just opposite that of the priest in which he determined to pray the latter to death. Superstition overcame the kahuna, who became so worried and upset by this situation that he eventually died. This turning of the tables on his enemy greatly increased Young's power. 6. Young and Davis are Active in Kamehameha's Government Both men were considered to be of good character and very influential, in their adopted homeland as well as among their own countrymen and men of other nations, as is documented by navigators, traders, missionaries, and businessmen. Their wise counsel and natural tact enabled the king to cope with the myriad of administrative matters involved in consolidation of his kingdom. Hawaiian chiefs and commoners, especially during the period of the disintegration of their traditional society, of necessity placed their confidence and trust in Europeans who not only could advise them on foreign customs but who, being independent of local politics, could also be trusted to act in the best interest of the Hawaiian people as a whole. A glance at the documents reveals that most visitors considered Young and Davis a good influence on the Hawaiian people, especially compared to most of the sailors and traders to whom the Hawaiians had theretofore been exposed. Young and Davis became an integral part of this early period of modern Hawaiian civilization, and for their efforts Kamehameha rewarded them by making them high chiefs and endowing them with large tracts of land on which they settled and raised families. This property was given particularly for their services in helping conquer the islands of Hawai'i, Maui, Moloka'i, and O'ahu. The land given to Young included Mailekini and Pu'ukohola heiau. Near their homes in Kawaihae, Young and Davis raised fruits and vegetables new to Hawai'i from seeds procured from foreign ships. Their residence in this area made it a required port of call for sea captains who had to obtain Young's blessing before conducting business with the Hawaiian government. In 1793 Vancouver landed the first cattle in Hawai'i at this spot. In 1803 Richard Cleveland, supercargo aboard the Lelia Byrd, left a mare with foal in Young's care at Kawaihae — the first horse ever seen in Hawai'i. In 1809 Young took the first horses and cattle to Honolulu, O'ahu. Davis served as governor of O'ahu during the early years of the nineteenth century. In 1810 he negotiated terms of peace for Kamehameha with Ka'umu'ali'i, the king of Kaua'i, bringing that island under Kamehameha's dominion. When Ka'umu'ali'i journeyed to Honolulu on board a foreign vessel to see Kamehameha, some lower chiefs conspired to kill him and proposed to Kamehameha that a sorcerer perform this deed. The king refused and even had the sorcerer slain. The chiefs then hatched a plot to kill Ka'umu'ali'i secretly as he journeyed into the interior. Learning of these plans, Davis warned Ka'umu'ali'i to return on board ship. Shortly thereafter, Davis died by poisoning, possibly in retaliation for this act of loyalty to Ka'umu'ali'i Davis's grave is located at Kawaihae. After the conquest of O'ahu, Young was designated governor of Hawai'i Island, an office that primarily involved superintending tax gathering for the king. He governed Hawai'i from his home at Kawaihae from 1802 to 1812 while Kamehameha attended to royal business on other islands; Young later became the resident chief of Kohala, with frequent assignments to Honolulu and elsewhere. Young kept closely apprised of political and military affairs in the kingdom, he being the one in 1816 to inform the king, then at Kailua-Kona, of the raising of the Russian flag in Honolulu and the initiation of construction of a Russian fort on the shores of the harbor in a first attempt to gain a foothold in the islands. Young carried back Kamehameha's orders to the Russians to leave immediately and then rebuilt the fort for Kamehameha's use. Prior to 1819 Young also modified Mailekini Heiau into a fort to protect the important Kawaihae harbor. As business agent for Kamehameha, as well as chief of the area, Young supervised the trade with ships at this port, where local salt and sweet potatoes, timber for ship repairs, hogs, fowl, taro, sugar cane, breadfruit, muskmelons, coconuts, and bananas were traded for nails, iron, and finally, at Young's suggestion, for more sophisticated types of goods. A lucrative sandalwood trade also originated here, with Young supervising from his home the measuring and loading of trees. Young was involved in, or witness to, most of the significant events in the early years of the Hawaiian kingdom. He was also present at Kamehameha's death in 1819 and participated in the secret burial of the monarch. He was also a guest of the royal court at the banquet in Kailua a few months later when Kamehameha II abruptly discarded the ancient Polynesian religion. There is no question that Young was sincerely devoted to the interests of his adopted country. Louis de Freycinet, who commanded a French expedition to the islands in 1817-20, noted that the death of King Kamehameha affected him deeply. Although Liholiho felt well disposed toward Young, their relationship could never match the Englishman's previous attachment to the young monarch's father. After Kamehameha's death, a degree of unrest existed among some of the principal chiefs regarding several economic matters, including the king's monopoly of the sandalwood trade. This tension in the political situation disturbed the elderly Young, who entreated de Freycinet to stress to the Hawaiians that peace and unity were essential for the future of the country and could only be attained by continuing loyalty to the Kamehameha dynasty. De Freycinet's draftsman, Jacques Arago, noted that

Young evidently had some religious inclinations, and, when counseled by Liholiho during the prolonged debate over allowing the American missionaries to land, helped arrive at a decision favorable to the newcomers. Young not only supported the missionaries' initial appeal to land, but maintained friendly relations with them afterwards. By persuading tolerance of these new arrivals, Young helped set a course that ultimately brought Hawai'i into the sphere of American influence and finally to statehood. Young's second wife was Ka'oana'eha, a niece of Kamehameha. Their children became intimately involved with the Kamehameha dynasty, several of his descendants holding important government posts until late in the nineteenth century. John Young II (Keoni Ana) served Kamehameha Ill as a member of the committee that paved the way for the Great Mahele. He served as kuhina-nui (premier) from 1845 to 1854 and as a member of the Privy Council. Kamehameha IV made him Minister of the Interior, a post he held until his death in 1857. James Young Kane-hoa, a son by his first wife, served as interpreter for Kamehameha II on that monarch's ill-fated trip to England in 1824. He also held the governorships of Kaua'i and Maui. Later he was a member of the first Board of Land Commissioners under Kamehameha III. Young's last descendant, his granddaughter Emma Rooke, married King Kamehameha IV in 1856. Her estate, administered by the Queen's Hospital, a facility for needy Hawaiians that she and her husband opened in 1859, included the lands at Kawaihae on which Pu'ukohola and Mailekini heiau stand. In feeble health, Young finally moved to Honolulu in the care of his son-in-law, an English physician, Thomas C.B. Rooke. (Rooke's wife was a sister of Fanny Young, Queen Emma's mother. The Rookes adopted Emma.) Young died at the latter's home in 1835 at the age of about 93. As a last gesture to an old friend, he made Isaac Davis's children equal heirs in his will. His remains and those of his granddaughter Queen Emma lie with those of other high chiefs and royalty of the Kamehameha dynasty at the Royal Mausoleum in Nu'uanu Valley, Honolulu. Unfortunately, and possibly because he was uneducated, Young wrote virtually nothing about himself or the happenings of his time, in most of which he was an important participant or at least a witness. His journal, spanning the years 1801 to 1809, located in the Hawaii State Archives, is primarily a log of taxes gathered. Young would have been able to provide invaluable accounts of Kamehameha's battles, the murder of his arch-rival Keoua, the dedication of Pu'ukohola Heiau and its subsequent use, the death and burial of Kamehameha I, and of the abolition of the kapu system. B. Foreigners Become Residents As a result of continued contact and trade by foreign ships, it was not long before some foreigners became permanent residents. By 1794 there were at least eleven non-native residents in the Islands, including Englishmen, Chinese, Americans, Irish, Genoese, and Portuguese. At Kawaihae in 1798 there were at least six foreigners, including John Young. Some foreigners had been left in the islands because of illness or to establish trade relations, while others jumped ship. While this latter group contributed little to either culture, they usually did not pose a serious threat to the Hawaiian rulers because they "worked under the chiefs." Some of the new residents were fugitives from justice and escaped convicts who "eked out an existence by living on the natives." Sometimes, however, the foreigners caused problems by refusing to submit to Hawaiian justice or by inciting unrest. Several times during his reign, Kamehameha issued deportation orders for all non-land holders, as did his successor Liholiho. However, it had become fashionable for important chiefs to have foreigners in their employ, and many of the newcomers were able to quickly establish themselves as associates of Hawaiian leaders. Many of the foreigners were allowed to stay on the islands because of their knowledge of firearms, navigation, and military warfare, while others were welcomed because of their background as skilled tradesmen. James Coleman, left behind on Kaua'i by Captain John Kendrick, was befriended by the chief of O'ahu and given considerable power and property. Coleman went on to regulate shipping and served as the chief's business representative, smoothing relations between the Hawaiians and foreigners visiting O'ahu. Kamehameha employed emigrant carpenters, masons, joiners, bricklayers, and blacksmiths and gave them generous grants of land. For example, by 1794 an English seaman named Boyd had taken up residence on the islands and had become one of Kamehameha's artisans, employed in the construction and repair of the king's fleet of vessels. It is likely that Boyd helped train many of the Hawaiian shipwrights stationed at Honolulu. Some foreigners like Captains Alexander Adams and William Sumner sailed ships for Kamehameha and Liholiho and were awarded significant land grants for their services. Williams Stevenson distilled brandy for the king, while John de Castro served as his personal surgeon and Welshman William Davis as his gardener. Some of the foreigners served in Kamehameha's military forces. William Broughton states that part of Kamehameha's confidence in the 1790s battles was due to the fact that he had fifteen Europeans with him. Other chiefs contended for the foreigner immigrants as well, perhaps hoping to counter Kamehameha's superior forces. Kamehameha had a number of trusted advisors among the foreign population. Several married into Hawaiian families, some, like John Young, Isaac Davis, and John Smith, marrying daughters of chiefs. They were endowed with lands upon which to settle and held important positions in Hawaiian government; they also, however, had to live under the kapu system. Padre Howel guided Menzies and his party to the summit of Mauna Loa and "had many long sessions with Kamehameha on the subject of Christianity." Jean Rives served as an interpreter at Kawaihae and later at O'ahu. An American named Oliver Holmes became the governor of Hawai'i following Isaac Davis's death and received large tracts of land on O'ahu and Moloka'i. A few of the immigrants operated as independent businessmen. For example, a certain Mr. Harribottle (ca. 1807) was the "chief purveyor of water" on O'ahu. Former slave Anthony Allen supplied milk, kept a boarding house, and cultivated land. Don Francisco de Paula Marin was an Andalusian Spaniard who settled on the island of O'ahu in 1791. He was a lack of all trades who married a Hawaiian woman and became closely involved with several Hawaiian leaders. He established a large ranch where he introduced a wide variety of fruits and vegetables, bred horses, processed beef for traders, and ran a distillery. Marin acted as an interpreter to the king, served as a doctor for members of the nobility, built a storehouse for Kamehameha, ran a boarding house, served as a tailor, commanded a ship, and dealt with sandalwood exports. He also reportedly built a stone house for Liholiho at Kailua, Kona, about 1813. During King Kamehameha's last days, Marin was called to his bedside in a futile attempt to save his life. After Kamehameha's death, Marin lost favor with the chiefs and had to struggle to make a living. One of the early foreign settlers was a New England sailing master named John Parker. He married a high-ranking Hawaiian woman and built a home on the west side of the island of Hawai'i. He adopted many Hawaiian ways and became well versed in Hawaiian history and legend. He bred horses and captured wild cattle to help build the Parker Ranch, which now occupies vast acreages of Hawai'i Island. (Parker's contributions to Hawai'i Island history will be discussed in more detail later.) C. The Impact of Foreign Influences on the Native Hawaiians 1. James Cook, George Vancouver, and Others Although James Cook's visits to the islands were short and spatially limited, they "set in motion some very basic changes in Hawaiian culture." Captain George Vancouver, who had first come to the islands with Cook, returned as commander of HMS Discovery in March 1792. Recognizing Kamehameha's exceptional leadership abilities, and knowing that trade would be most profitable in a stable political climate, Vancouver sought to reconcile the warring island chiefs and refused to sell the natives guns and ammunition. However, Vancouver had another agenda as well. He carefully planned his campaign to transform Kamehameha's chieftainship into a kingship and to acquire Hawai'i for Great Britain. Vancouver's actions and his support of Kamehameha helped establish the basis for the united Hawaiian kingdom. Vancouver's visit also had a long-lasting effect on the islands' economy and environment. He recognized the utility of introducing new species to provide food and subsistence items for both foreign traders and native peoples. He brought goats, sheep, and cattle from California for Kamehameha in gratitude for the king's kind treatment of foreigners. The cattle — saved from slaughter by a kapu — multiplied rapidly and were reported running wild by 1807. Vancouver gave the Hawaiians a variety of garden seeds, among which were "stone fruits" from Monterey. He also provided men and materials to build a ship for Kamehameha, As mentioned in an earlier section, the impact of foreign customs, beliefs, and institutions upon the native Hawaiians was far reaching, resulting in abolition of the kapu system, changes in religious and social mores, reforms in the land tenure system, introduction of new tools and technology, and reshaping of the economic system. In addition, the introduction of new species initiated major ecological changes. 2. Diseases and Liquor Because of their centuries-long isolation from other islands and continents, the Hawaiians had no immunity to diseases such as smallpox and measles that foreign visitors introduced. Despite Cook's efforts to protect the native population, venereal disease arrived in the Sandwich Islands through members of his expedition on their first visit. Upon his return in late 1778, Cook was saddened to see the effects of the disease already visible among the natives. Over the next decade, the native women continued to entertain visiting sailors, although many of the captains tried, generally in vain, to contain the contagion by keeping their sailors aboard ship. Venereal disease would be responsible for sterility, considerable illness, and even death among the population, but other diseases created distress as well. Visitors observed depopulation as early as about 1807 due to a "kind of epidemic or yellow fever." Kamehameha's plans to invade Kaua'i were aborted by an epidemic causing illness and death among his army. By 1819 the population of the islands had decreased drastically. Only in the second decade of the twentieth century would the Hawaiian population rise again to the estimated 1778-79 level. Although the people of the Sandwich Islands made and drank a hypnotic brew known as 'awa as part of their religious activities, the art of distilling hard liquors, especially rum, was supposedly introduced into the islands sometime before 1800 by Botany Bay convicts. There were a number of sources for the liquor. Iselin, writing in 1807, reported Englishmen living on O'ahu who invited the sailors for beer and a kind of gin made from the tea root, "said to be drank freely in these Isles." The Spaniard Don Francisco Marin, who was operating a distillery on the island of O'ahu by 1807, was furnishing at least some liquor. When the Hawaiians of important rank came aboard ships, they drank freely. Brandy and rum imported for resale were consumed in such large amounts by the natives that within a few years drunkenness had become a major problem, especially among the royalty. Liquor was probably responsible for much of the capricious behavior exhibited by Liholiho. 3. New Economic System, Trade, and Technology The pre-contact Hawaiian society was economically self-sufficient, with management of resources and redistribution of goods effected through the land tenure system and through religious rituals like the Makahiki festival, through the kapu system, and through payment of tribute. Enough surplus food was produced to support the chiefs, priests, and craftsmen. However, Cook's visit set in motion events that would eventually effect a major change in this economic system from a subsistence economy to a supplementary food market economy. Trade between Europeans and native Hawaiians was one of the most important catalysts of cultural change. Traditionally, large-scale trade had not been an important part of the subsistence economy of the Hawaiian Islands. At first, contact with Europeans was sporadic, and trade was conducted on a piecemeal basis, usually controlled by individual chiefs. As more traders came to the islands, the finely balanced system of supply and demand was disrupted, which eventually led to the demise of the traditional subsistence economy. This change in the islands' economic base was exacerbated by the singular differences between the two cultures. For example, the Europeans were accustomed to a society where the means of production were privately owned and profits were expected. Hawaiians, on the other hand, were part of a society that shared work and its products for the welfare of the larger community. According to Marion Kelly, the

Changes in the Hawaiian society went deeper than simple economics. The Hawaiian's value system included aloaha aina, an "ideal that expressed the land's meaning" to the islanders and "insured the preservation, the conservation, and the balance of life-giving resources of land and sea." As this cultural value was diminished, concomitant economic changes disrupted the delicate resource balance. During the early Western contact period, Hawaiian farmers were able to increase the production of goods and commodities to meet the traders' demands and satisfy the needs of the ali'i without a major dislocation of island economics. Hawaiians quickly learned the value of their goods and showed a strong ability to barter. On Hawai'i, early traders found plentiful sugarcane, breadfruit, coconut, plantain, sweet potatoes, taro, yams, bananas, and hogs as well as introduced oranges, watermelon, muskmelon, pumpkin, cabbages, and garden vegetables. Initially the Hawaiians wanted bits of iron and beads for these products, but by 1790 firearms, gunpowder, and liquor had become prized trade items. One critic complained that the European traders "commenced implanting among the chiefs the taste for ardent spirits." It was not long before Hawaiians began to demand clothing, cloth, pitch, flour, and other western products. As described by one trader, "the islanders . . . ceased to care for objects of mere ornament, and preferred in their traffic cloth, hardware and useful articles." By about 1790, the demands of traders and explorers had begun to adversely affect the traditional Hawaiian subsistence economy, which was also under stress from ongoing warfare, which drained labor and resources away from the native farms. For example, visiting traders remarked that most of the hogs on Hawai'i were destroyed when their owners left to join Kamehameha in his crusade against Ka'umu'ali'i. The once flourishing vegetable gardens on the west coast also perished through neglect. Trade for guns and weapons only accelerated the process. Inter- and intra-island warfare posed an inconvenience to the traders. The chiefs often put trade under kapu while they were away in battle, and some even used force to obtain needed guns and ammunition. Like a number of chiefs, Kamehameha played the traders off against each other to gain a trading advantage. Captain Vancouver was the first to recognize that a stable, peaceful, and politically unified Hawaiian government would benefit trade and strongly supported Kamehameha in his conquest. Kelly suggests that without the political unity fostered by Vancouver, "later changes in land tenure might never have occurred." After about 1796, peaceful conditions generally prevailed across the islands. As more trading ships called at island ports, local communities began to suffer deprivations. Sometimes food and water were plentiful, but at other times the natives had little to offer to trade. According to Kelly, pork was one of the most popular trade items. Reductions in the supply of hogs due to increased trade may have encouraged a renewed dependency on fish by the native population, which then might have resulted in a return to seashore areas from inland farms. Increasingly goods became unevenly held and distributed across the islands. Some of this was due to geography; some parts of the islands were far more arable than others, and the rainfall differential between the windward and lee sides of the islands produced a much different crop potential. Also, traders tended to visit ports like Kealakekua and Lahaina, and later Honolulu, where they could generally obtain supplies and fresh water at lower prices and also feel safe from attack. As commerce increased at those ports, native populations began a subtle shift to those areas. As trade increased, more and more labor was drawn away from subsistence production to provide food, fuel, and water for the traders in return for Western clothing, metal, and even luxury items. The chiefs precipitated and encouraged some of the cultural changes associated with trading. Before Kamehameha's ascent to power, individual ali'i effectively controlled large amounts of wealth through their regulation of the trading canoes. The chiefs increasingly sought luxury goods in exchange for food and fuel. These goods did not, however, filter back to the commoners through traditional means; in fact, some Hawaiian chiefs confiscated trade goods that commoners received. It is likely that the health and general welfare of the people decreased during this time because there were fewer subsistence items left for their use and because so much of their energy was spent in supplying goods for the traders. As many of the chiefs sought to establish a relationship with the Europeans in hopes of acquiring gifts and weapons, they often served as middlemen or brokers in trading situations. This was a natural extension of their relationship with the commoners, and "it was this convenient adaptation that facilitated the chiefs' rapid acceptance of western trade practices." In turn, the ready acceptance of these foreign customs by the chiefs served as an example to the commoners. Unfortunately, the acceptance of foreign customs and products also marked the increased exploitive role of chiefs toward the people, which peaked during the sandalwood trade. Other changes in the economic system were encouraged by the new plants and animals introduced by the early traders and explorers. These items quickly took hold in the islands and displaced more traditional foodstuffs on the small farms. These new items were generally used in trade rather than for local consumption. Cook introduced European plants to the islands — including pumpkins, melons, and onions — and also brought English pigs, goats, and sheep. Captain William Broughton had his men plant grapevines and vegetable fields during the ship's visit. He complained that "pumpkins and melons were in no great plenty," but the excellent island cabbages weighed nearly two pounds. By 1791 seamen were able to trade for pumpkins and watermelons. The cattle that Captain Vancouver and other traders left swiftly multiplied because of a ten-year kapu the king placed on their use. According to Kotzebue, by 1821 the wild herds were so large that Spaniards from California came frequently to the islands to capture them. Vancouver also introduced goats to the islands; by 1796 these had multiplied prodigiously. In 1796 Captain William Broughton gave the islanders another pair of goats, along with geese, ducks, and pigeons. Horses were introduced onto the island of Hawai'i in 1803 by Captain Cleveland as a gift to King Kamehameha. At least two breeds of swine were being raised for the traders, native pigs having been interbred with those the sailors brought. The introduced livestock did not appear to have been used by many Hawaiians for food. Instead the animals destroyed crops, helping disrupt the islands' ecology and accelerating the removal of ground cover leading to erosion. When sold to traders, the pigs and cattle were usually butchered and salted down before the ships left the islands, creating yet another new industry for the islanders. During the early 1800s, so many traders called at the islands demanding pork and other goods that supplies of hogs and produce were often exhausted. European traders were no longer able to procure large amounts of goods in exchange for a handful of nails or other metal. Although at one time a hog could be acquired for a few pieces of rusty iron, by 1807 the standard price was a greatcoat and a cask of powder. Sailcloth, tar, and pitch (for Kamehameha's navy) were also much in demand. By 1810 a number of Hawaiian traders were demanding luxury goods and cash. Iselin describes the high prices for hogs — $4.00 each in specie, plus several yards of expensive scarlet broadcloth (worth perhaps $3.00 per yard) plus up to twenty yards of linen sheeting. Americans were described as the best customers, and by the time the missionaries arrived, four American mercantile companies had established themselves in the islands. Once in power, Kamehameha made a number of changes that resulted in formalization of relationships with foreigners. He made trade a royal monopoly and took pleasure in driving a shrewd bargain. Trade was regulated, and a certain protocol was necessary when foreigners entered port. Incoming ships had to call upon the king or upon the island governor (or one of his representatives); Kamehameha provided harbormasters to guide the ships and appointed special "confidential men" who served as intermediaries between the traders and the island governors. He also attempted to control production and distribution through use of the kapu system. The economic system was also changed by the new and different labor needs. Traditional activities, often related to subsistence or religion, were increasingly replaced by other tasks. The islanders readily learned important new crafts and skills like shipbuilding and blacksmithing and quickly adapted new technologies to traditional needs. Natives now served as laundrymen, messengers, guides, servants, and boatwrights. One of the major industries that developed on the islands was ship repair; ships calling at the Sandwich Islands were often repaired by native craftsmen under the direction of the ship's carpenters. Kamehameha encouraged this industry and built boat sheds on the shores of O'ahu. This activity was fairly labor intensive, for repair of a mainmast might involve 300 people who dragged the timber with ropes six to eight miles down the mountainside. Again, these duties pulled a substantial number of workers away from their traditional farming practices. As early as the 1790s, the New England traders picked up men on Hawai'i to serve aboard the sailing ships or purchased youngsters as servants. Soon Hawaiian sailors were visiting American coastal towns; by 1807 Hawaiian sailors could be found in the ports of New York. They brought ideas from abroad home with them, thus contributing to the cultural changes. 4. Kapu System Weakened Well before the formal end of the kapu system, there were signs of weakening in the authority of the priests, especially over women. While the rules forbade women to watch a man eat pork — or to consume it themselves — on board ship they would "partake, in stealth, of what was handed to them, and would peep from behind the screen of a stateroom, to see the men eat." 5. Population Shift and Growth of Towns When Vancouver's ships stopped along Hawai'i's west coast in 1793-94, more than 3,000 people came to greet them at Kealakekua Bay, suggesting a fairly large population in that area. However, between Vancouver's visit and 1819, a gradual shift of population away from Hawaii's west coast to other areas began. Several factors may have accounted for this: as the importance of O'ahu and the port of Honolulu grew, more ships began to call there and more people went there to interact with the foreigners; also Kamehameha and his retinue began to spend more of their time on the other islands, and ali'i and commoners alike tended to cluster around his court. Disease may have played a role in population decrease in certain areas, and ongoing warfare, causing abandonment of farms, certainly was a strong factor. 6. New Class of Foreigners — Part-Hawaiians By the year 1800, there were a number of children of mixed heritage resulting from two decades of contact between native women and foreign traders. The majority of these children were raised in the traditional Hawaiian manner. In addition the islands supported a small but growing number of foreign residents who had married Hawaiian women. Some, like John Young, married into Hawaiian royalty and lived their lives according to the rules of Hawaiian society but sent their children abroad for schooling. Some Hawaiians took in the children of foreigners; Kamehameha's prime minister in 1807, a chief named Teremotoa, cared for the children of a Captain Hart, who had died on O'ahu, along with those of several other white men. Some part-Hawaiians were regarded as native residents, such as George Holmes, son of Oliver Holmes and a Hawaiian woman. Many of these children went on to become their country's leaders in later years. 7. Facilitation of Kamehameha's Rise to Power During the 1790s, warring Hawaiian chiefs often demanded powder or guns in return for their produce. For example, when Vancouver s ships first stopped at Kawaihae to trade, they were able to purchase vegetables with nails and beads but "the hogs they [the Hawaiians] would not at first part with but for muskets." Some traders (especially Vancouver) tried to ameliorate antagonisms among the various chiefs, but others encouraged the distribution of guns and powder as a form of bribery to obtain preferential trading privileges. At the time of Western contact, the Hawaiian Islands were already on the road towards state formation. Unquestionably, Western technology, and especially guns, played a major role in speeding up the process by facilitating Kamehameha's rise to power. Recognizing the value of ships, arms, and ammunition in warfare, Kamehameha set out to acquire Western technology and skilled technicians. His first venture was to take possession of the schooner Fair American and its big guns in 1790. He also acquired a number of small arms and ammunition. In 1796 one explorer noted that European vessels had furnished Kamehameha with such a large supply of muskets and ammunition, and numerous three- and four-pounders (cannons), for his boats, that he "presumes his force is equal to any." John Young and Isaac Davis, both experienced seamen, provided technical assistance and military advice. Kamehameha convinced Captain Vancouver to assist in the construction of his first ship; by 1807, Kamehameha had built or acquired a navy of his own, consisting of a large ship (the former Lelia Byrd, an American vessel), several large three-masted schooners, and about twenty-five small vessels of twenty to fifty tons. He employed Euro-Americans both to construct his ships and to serve in the military. |

||||

|

Chapter 4: Founding of the Kingdom Back to Contents Back to History |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |