A

Cultural History of Three

Traditional Hawaiian Sites

on the

West Coast of Hawai'i Island

Overview of Hawaiian History

by Diane Lee Rhodes

(with some additions by Linda Wedel Greene)

|

Chapter 7: Pu'ukohola Heiau National

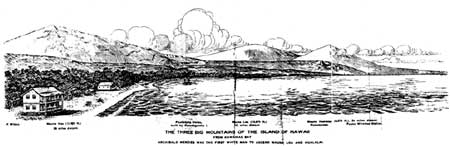

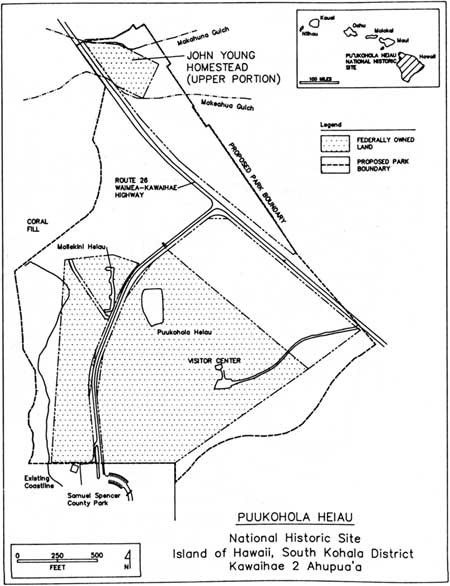

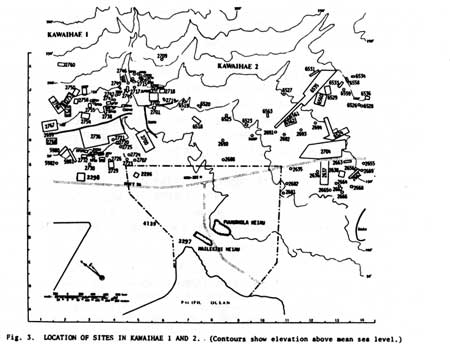

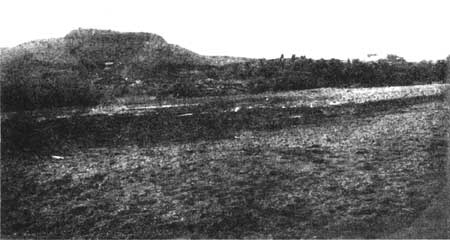

Historic Site A. Setting of the Park 1. Village of Kawaihae The terraces of Pu'ukohola Heiau dominate the side of a prominent hill overlooking Kawaihae Bay. Despite the nondescript nature of the early village of Kawaihae, as recorded in the journals of early Euro-American voyagers to the islands, it has played a conspicuous role in Hawaiian history. In both prehistoric and historic times, its spacious natural harbor has distinguished it from the other coastal settlements of leeward Kohala, making it not only the safest mooring spot in that district, but also one of the best anchorages on the island of Hawai'i. Kawaihae is where Kamehameha confirmed his position as ali'i-nui of the island upon the death of his chief rival, and it remained his residence from about 1790 to 1794 while he planned the invasion of the other Hawaiian Islands. According to Marion Kelly, Kawaihae was a popular surfing area in ancient times. The name means "Water-of-Wrath" and refers to the battles over the life-giving waters of one of the springs in the area. Kelly states this water source reportedly was destroyed by harbor development, but it could also have been impacted by destructive high floodwaters in the gullies during heavy rains. According to trader William French, who owned a store in Kawaihae, the settlement was extremely active during the time of Kamehameha's reign. Its harbor and its proximity to the fertile uplands of Waimea ensured its status as an important stopover for many early European voyagers and merchantmen needing to make repairs and resupply their ships. Because King Kamehameha firmly controlled all trade and other intercourse with Euro-American ships, all sea captains arriving in the Hawaiian Islands had to obtain his permission before initiating any activities with his subjects. Therefore ships were constantly stopping at Kawaihae to pay their respects and gain his blessing when he was in residence. If he was not there, visitors contacted John Young, Kamehameha's business manager and governor of the island from 1802 to 1812, an important foreign political figure who, while he lived at Kawaihae, exerted a strong influence on its social, political, and economic life, and about whom more will be presented later. For all the above reasons, for many years Kawaihae served a crucial role in the importation of foreign goods, the distribution of local products, and the spreading of new ideas and mores during a time of great change for the Hawaiian people. After Kamehameha's death, it was to this place his son returned from the royal residence at Kailua to unite his supporters, formulate his policies, and consecrate his new leadership role.

2. Historical Accounts of Kawaihae Bay Area The earliest European observers of Kawaihae Bay were members of Captain James Cook's exploratory and scientific expedition. Arriving at the mouth of the bay in February 1779, they were little impressed, Captain James King noting that

A month later, revisiting the harbor after Cook's death, King still found nothing of particular interest:

George Vancouver, captain of the Discovery, visited Kawaihae in February 1793 and found a watering place

Going on shore to visit the inhabitants, Vancouver noted that

Captain Richard J. Cleveland, anchored off "Toiyahyah" Bay in 1799, described the approach of a large number of canoes carrying hogs, potatoes, taro, cabbages, watermelons, muskmelons, sugarcane, and a variety of other produce for trade. A local chief came on board to maintain order and regulate the number of persons allowed on the vessel at one time. He also acted as a broker for the crew and as a facilitator for the bartering process. Isaac Iselin, supercargo on the Maryland, visited Kawaihae in the early 1800s:

Iselin also mentions visiting "several salt ponds or pans, the arrangement of which displays much industry and ingenuity." Jacques Arago, draftsman on the French expedition (1817-20) under command of Louis de Freycinet (in the corvette Uranie), noted that

De Freycinet described the town in terms equally unflattering:

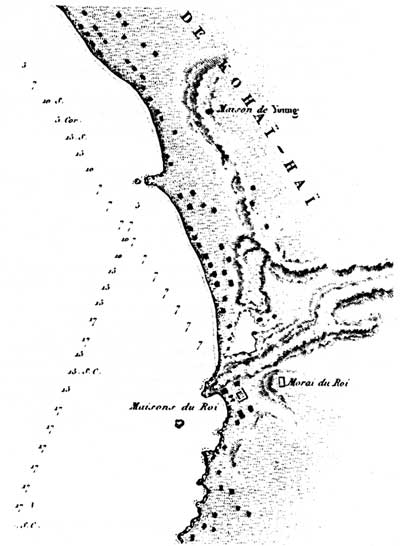

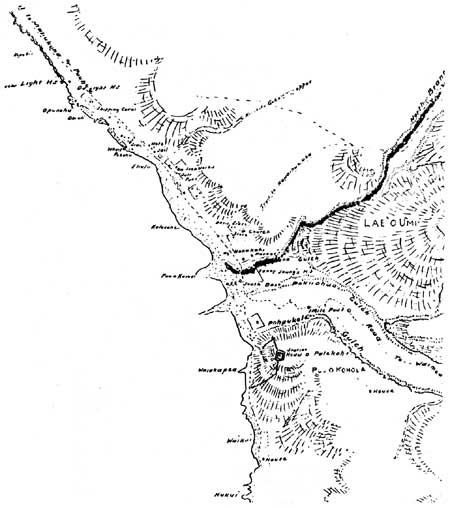

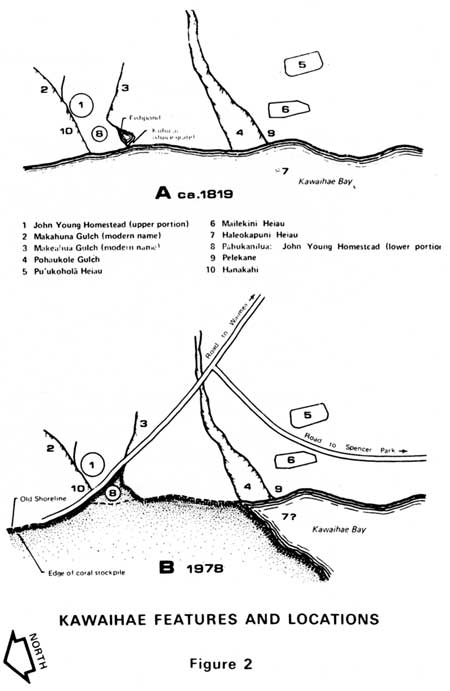

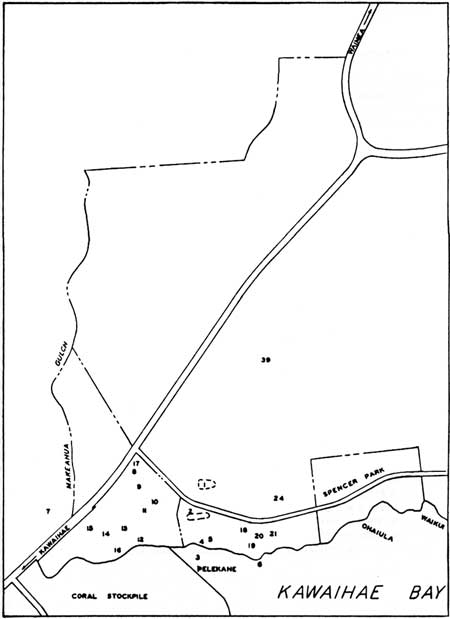

3. Historical Appearance and Activities of Kawaihae a) Fishponds Frenchman Louis Duperrey, an officer of the de Freycinet expedition, drew a map of Kawaihae Bay in 1819, showing about ninety structures along the shoreline (Illustration 27). The main portion of the settlement contained three rows of houses parallel to the coast. The first group abutted the shore, with the last row lying near the base of the Kohala Mountain slope. This map also delineates a small inland body of water, probably one of two fishponds that existed there. One was located near the homestead of John Young at the mouth of Makahuna Gulch; the other lay near the old salt pans to the north. Historian Russell Apple has determined that the Makeahua pond existed from before 1819 at least through 1848.

b) Salt Pans The salt pans constructed for the extraction of salt from sea water were an extremely important aspect of Kawaihae's subsistence perhaps its major industry for many years. Because of its shoreline's lack of fertility, Kawaihae was always foremost a fishing village; in the mid-1830s it was reportedly the best place to buy fish on the entire island. This distinction resulted not only from its abundant marine resources but also from its status as an important trading center to which people from other communities along the Kohala coast brought their catches. The ready availability of salt there allowed the immediate preservation of excess fish for use as trade items or for future local need. The locals traded this salt to Kona as well as other sections of Kohala for the necessities they lacked such as cultivated food and kapa. Hawaiian salt, used to season and preserve fish and meat, was one of the first items of exchange between the natives and foreign fur traders in the early nineteenth century. Extensive areas in certain parts of the islands were reserved for the production of this commodity. On Hawai'i Island, Kawaihae boasted the largest salt pans. Hawai'i exported salt from around 1840 to 1881, reaching a peak production about 1870. Hawaiian salt was later used in curing hides in addition to salting meat, requiring construction of larger pans as the Waimea cattle industry expanded; these were destroyed by a tidal wave in 1946. According to Marion Kelly, Kawaihae informants told her the earlier salt pans had been destroyed during construction of the modern harbor. As Reverend William Ellis traveled around the island of Hawai'i in 1823, he visited Kawaihae twice, recording 100 houses there in 1824. Ellis mentioned several interesting activities and sites in Kawaihae, including some warm springs a short distance south of the heiau, in which he enjoyed a refreshing bath:

Ellis also described salt production at Kawaihae, noting that Hawaiians partook of this item liberally with their food besides utilizing large amounts to preserve their fish catches:

c) Sandalwood Trade On his second visit to Kawaihae, Ellis stayed with John Young, where, one morning

The sandalwood trade was another extremely important industry in this area a commercial activity that reached its peak in the 1820s. At this time the Kohala Mountain forests were abundant, reaching almost to the Kawaihae shore in 1815. John Young oversaw the measuring and loading of logs, while, according to Ellis, thousands of natives were forced to cut and haul timber, penetrating ever deeper into the interior as supplies dwindled. This intensive business venture denuded the forests and precipitated their retreat inland. The prospering herds of wild cattle and goats in the Waimea area prevented new growth from surviving, as did the diversion of streams to support the community there. All these factors contributed to Kawaihae's appearance as a desolate place. 4. Missionary Activities at Kawaihae American missionaries arrived in the islands in 1820. During a brief sojourn at Kawaihae they met some members of Hawaiian royalty, including two of Kamehameha's widows. The Reverend Hiram Bingham also visited Pu'ukohola Heiau with the high chief Kalanimoku and left a description of the structures that will be presented in the next section of this report. Because the new king was living in Kailua at this time, however, the missionaries' ship proceeded on down the coast to ask his permission to begin their work.

Kawaihae was the site of one of the first mission stations in the Hawaiian Islands, although it was only briefly looked after by Elisha Loomis beginning in 1821. Kawaihae and Puako were ultimately included in the area served by missionaries Dwight Baldwin from 1832 to 1835 and Lorenzo Lyons from 1832 to 1876. Lyons landed at Kawaihae in 1832 before proceeding to Waimea to establish a station. He noted that Kawaihae was "about as desolate a place as I have ever seen, nothing but barrenness, with here and there a native hut." His Waimea parish eventually included the districts of Kohala and Hamakua, making it the largest mission station in Hawai'i. During his tenure, Lyons was responsible for the erection of fourteen churches, including one at Kawaihae. Kawaihae had supported some type of meetinghouse since the earliest days of the Protestant mission, though it amounted to little more than a rude grass sanctuary. In 1843, however, the parish began construction of a stone meetinghouse, probably covered by a thatched roof. Stones for the walls were found nearby, while coral collected from the beach was burned to produce a lime for mortaring. The final dedication ceremony on January 13, 1859, involved a procession, prayers, speeches, and songs. Toward the end of the service, the parishioners marched over to the old heiau of Pu'ukohola where they prayed and sang. This church underwent renovation in 1884 and repairs in 1903; it was torn down in 1959. 5. Cattle Industry in the Kawaihae-Waimea Area In time it was the lush pastures of the upper slopes of Kohala Mountain that sustained the Kawaihae economy. Travel between the two areas was possible via a number of trails that led from the seacoast, past periodically cultivated agricultural plots, to the Waimea Plain. In the early 1820s three major population centers existed there, about two miles apart, at Keaalii, Waikoloa, and Pu'ukapu. After the supplies of sandalwood and pulu disappeared, resulting in the failure of those business enterprises, South Kohala turned to cattle for its livelihood. The cattle industry had begun in the early 1800s with government-controlled bull hunting. An American who greatly impacted this activity was John Palmer Parker, a seaman who came to Kawaihae in 1815 and then moved to Waimea. Enlisted to hunt wild cattle on the slopes of Mauna Kea, he was to thin the herds, descended from cattle introduced by Vancouver, that had multiplied so rapidly that they were a danger to people and destructive of the landscape and cultivated upland fields. The government and king, who jointly owned all the wild cattle on Hawai'i and sold or leased slaughter rights to private parties, encouraged the capture of these animals to procure beef, hides, and tallow. Because Hawaiians did not yet eat beef, it was the needs of the whalers, arriving in great numbers in the 1840s, that spurred this enterprise. Parker soon built up a thriving business with foreign, and later interisland, trading vessels in meat treated with salt from Kawaihae and tanned hides. Over the next thirty-two years, Parker expanded his activities, importing Spaniards from Peru as ranchhands and shipping out hides, tallow, and soap. Parker received two acres of land on the Waimea Plain from King Kamehameha Ill in 1847; this landholding ultimately developed into the famous Parker Ranch. Exporting its cattle became Kawaihae's principal activity. The wild descendants of Vancouver's original cattle comprised the herds of Hawai'i's first ranches prior to 1830. After that time, however, as a flourishing by-products industry took hold, most wild cattle were killed, and imported animals were brought in to stock the ranches. The cattle industry slowed in the late 1830s and early 1840s due to overkilling. By 1850, however, cattle raising was again a thriving industry in Waimea, with cattle driven to Kawaihae for shipment to Honolulu's slaughterhouses. The old road between Waimea and Kawaihae is supposedly the route of the historical Parker Ranch cattle drives. More modern cattle holding pens are located across from the small boat harbor; the massive rock walls near the present canoe club are said to be the remnants of older corrals where cattle were held until shipment.

6. Agricultural Activity in the Kawaihae-Waimea Area A slight decline in Hawaiian agricultural production began in the 1830s. Author and journalist James J. Jarves described Kawaihae in the late 1830s as

Agricultural activity revived somewhat in the late 1840s and early 1850s, primarily due to the demand for sweet and Irish potatoes. Although the former had always been a much-sought-after item for ships' stores, it was not until the early 1830s that Irish potatoes were also cultivated in Hawai'i. Increased whaling activity after 1840 brought new demands for both types. Another short-lived increase in potato production began in 1849 to help make up for a lack of that vegetable in California during the Gold Rush. This trade had diminished by 1852, although that with whalers continued for several more years. In 1853 Edward T. Perkins, anchored in a ship off Kawaihae Bay, judged this to be

By 1857 Kawaihae was described as an important port shipping produce from the rich uplands of Waimea, one of the finest agricultural districts in the islands:

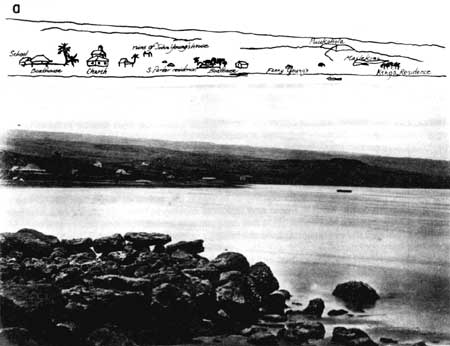

Other exports included fresh beef, pork, fowl, beans, wool, bullock hides, goatskins, and tallow. By the mid-1800s, then, Kawaihae hosted an active port, where visiting ships low on provisions traded foreign goods for produce, sandalwood, pulu, firewood, fresh water, and local salt. While there, the ships' officers usually met with any high-ranking personnages who happened to be in the area. An 1880s photo of the Kawaihae landing (Illustration 30) shows a group of buildings that may include William French's warehouse for storing sandalwood, wool, salted beef, and hides to be shipped to Honolulu or California in the 1830s and 1840s. French obtained property near the landing from Governor Kuakini in 1838 for the storage of cargo.

7. Decline of Kawaihae The Reverend Lorenzo Lyons noted in 1841, while preaching in Kawaihae, that its population stood at 726 people, 300 less than the previous year. His letters attribute this decrease to its being such a "wretchedly poor place," offering so little to eat that families were forced to relocate to more fertile regions. Throughout the 1800s, the population of the Waimea-Kawaihae area seems to have been in decline. It probably fluctuated due to a number of circumstances, including people moving periodically to certain areas for specialized public work projects, such as coming in from all over Kohala to build Pu'ukohola Heiau or to carry sandalwood from Waimea to Kawaihae Bay. Other population shifts would have involved families visiting relatives elsewhere for periods of time; chiefs and their entourages moving from site to site, always attracting the curious and various hangers-on; neighboring residents coming in to watch the arrival of ships, anxious to see the foreigners and engage them in trade; and residents moving to other places for new and better commercial opportunities. In addition to this constant movement, reduced fertility and increased mortality changed the population figures. A smallpox epidemic in Kawaihae in 1853, for instance, took half the population. Isabella Bird Bishop, visiting Kawaihae in the 1870s, was able to make the small town seem appealing despite the slow tempo of its life:

By 1890 Henry Whitney reported that:

Caspar Whitney verified this view of Kawaihae's decline in 1899:

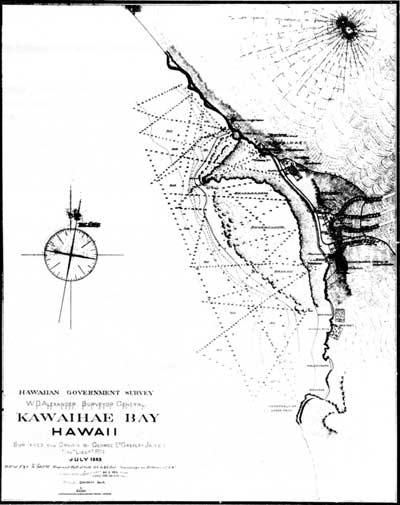

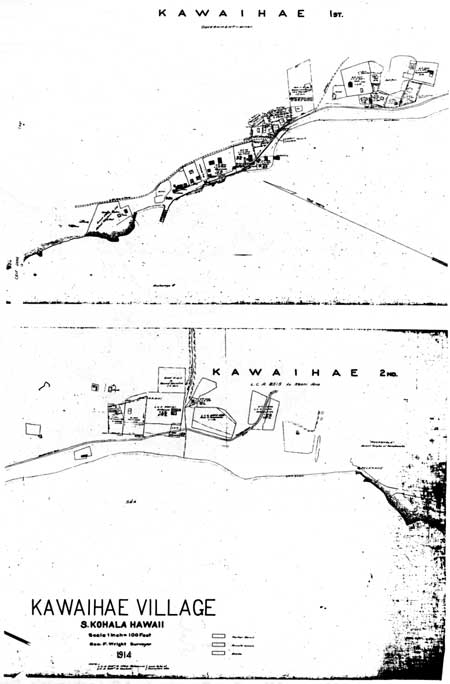

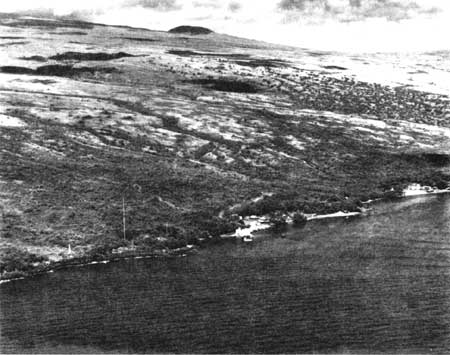

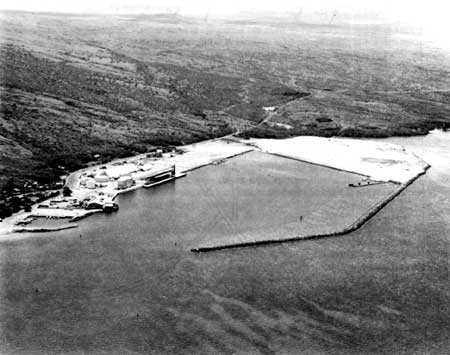

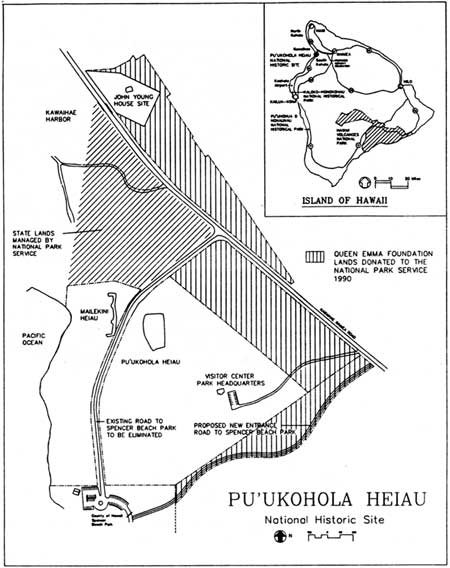

8. "Modern" Kawaihae Village Not until modern times, with the dredging of its harbor and the opening of luxury resorts, did the forgotten village of Kawaihae again become a prominent site on the Kohala coast. In 1949 construction of a deep-draft harbor was recommended for the bay, which by that time was a small port shipping sugar, steers, pigs, and sheep to market on interisland vessels. In 1957 a contract was let to build causeways, a dike, and a revetment; the new deep-water port of Kawaihae Harbor was finally completed in 1959. Three years later the Corps of Engineers decided to widen the harbor's entrance channel and its basin, extend the existing breakwater, and construct a small boat harbor. By that time the Corps and the Atomic Energy Commission had begun a joint research program focusing on the use of nuclear explosives for construction purposes. Some of the types of projects amenable to nuclear excavation included water channels, highway cuts, harbors, and dams. The army's Nuclear Cratering Group was anxious to try chemical high explosives in excavating the small boat harbor and entrance channel at Kawaihae. "Project Tugboat" would be the army's first major construction project using that method of excavation. Some local opposition arose, concerned about detrimental impacts on marine life and on historically significant structures such as the nearby heiau. Before setting off the explosions, engineers braced the walls of Pu'ukohola Heiau and placed a seismograph next to the structure to monitor movement. Three phases of detonations were required to accomplish the job, which also involved construction of an 850-foot-long breakwater to protect the new basin. The project was considered a complete success, but expensive. No known damage occurred to historic structures. Today Kawaihae Bay and its coastline differ drastically from the views described in historical journals. In Young's day, the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, the original hardwood forests stretched almost to the beach. Freshwater streams flowing down gulches from Kohala Mountain provided the water supply of Kawaihae and potable water for ships. Ultimately logging activities related to the sandalwood trade and to the repair of visiting ships, clearing for agricultural terracing, and uncontrolled cattle grazing and tree removal caused the forest to recede. As streams dried up, erosion intensified, creating a semi-barren desert environment. While the town evolved into a specialized port for salt and cattle-related products, many of its residents left for the bustling major ports such as Lahaina and Honolulu. During excavation of the harbor, the dangerous coral reef, which formerly stretched just under two miles south from the area of the town, was cut and scraped and the dredged material formed into a landfill to support the harbor terminal facilities, oil storage tanks, and other buildings. Excess material was stockpiled and its outer edge revetted with stones. Kawaihae village itself also little resembles the settlement seen by early European explorers and merchants. It consists of frame dwellings, a few stores, and other local businesses. Kawaihae is now a major shipping center for raw sugar. Structures in the harbor facility include storage tanks for oil and molasses, a bulk sugar warehouse and conveyor system for loading ships, a metal warehouse, a service terminal, and a concrete bulk chemical warehouse. The town is also the major supply point for Pohakuloa Training Area. Development farther south along the coast includes Spencer Beach County Park, residences, and the Mauna Kea Beach resort hotel. Two highly visible structures in Kawaihae served as landmarks for ships heading into Kawaihae Bay in the early historic period. One was the grave of George Hueu Davis, son of Isaac Davis. The other was the grave of George W. Macy, a sea captain who was in business with an early Waimea merchant. Macy's grave was described as a "conspicuous white obelisk" on a hill behind the village. Significant prehistoric and historical manmade structures around Kawaihae include numerous stone features of early Hawaiian civilization such as agricultural enclosures, homesites, fishing shelters, and graves. The ruins of John Young's Kawaihae home overlook the bay, and two structures of extreme importance in Hawaiian history Pu'ukohola and Mailekini heiau still stand quietly by the sea. The history, appearance, and significance of these structures will be discussed in the next section.

B. Pu'ukohola Heiau 1. Traditional Construction History a) Hawai'i Island Politics at Euroepan Contact At the time Cook discovered the Hawaiian archipelago, Kalani'opu'u ruled as paramount chief of the island of Hawai'i and the Hana District of Maui. During the fierce interisland warfare of this period, the young chief Kamehameha highly distinguished himself as a warrior in Kalani'opu'u's army. Before Kalani'opu'u died in 1782, he designated his son, Kiwala'o, to succeed him as high chief; in accordance with the custom in those days of splitting power, he also named his nephew Kamehameha custodian of the state god Ku-ka'ili-moku. Kamehameha first revealed his political ambitions shortly after this by offering up a human sacrifice the leader of a failed uprising usurping Kiwala'o's prerogative as designated future ruler. As punishment for this infringement, Kalani'opu'u dismissed Kamehameha from his court. Hostilities between the rival supporters of the son and the nephew resurfaced upon Kalani'opu'u's death. At the battle of Moku'ohai, Kona, in 1782, Kiwala'o met his death at the hands of Kamehameha's supporters. This left his younger brother Keoua Kuahu'ula as the chief contender with Kamehameha for sovereignty of the island. The situation was further complicated when Keawemauhili, the chief of Hilo and Keoua's uncle, declared his independence, splitting the island into three rival factions.

b) Kamehameha Begins His Bid for Power Kamehameha, reigning over the western part of the island, with its favorable anchorages at Kailua and Kealakekua Bay, gained a distinct advantage over his foes by acquiring not only the benefits of European ideas and military strategies, but also advanced technology such as arms and gunpowder. By 1790 he had managed to acquire guns, light cannon, and an armed schooner, in addition to the advice and technical expertise of two European seamen, John Young and Isaac Davis. Setting aside for the moment his ambitions on his own island, however, Kamehameha decided to invade Maui, where he defeated its defending army but failed to capture the important chiefs. When Kamehameha pushed on toward Moloka'i, Keoua took advantage of his absence, and, defeating Keawemauhili, invaded his other rival's territory, laying waste Hamakua and Kohala. Quickly returning to defend his lands, Kamehameha secured them but did not defeat Keoua and decided to again invade Maui. It was during Keoua's retreat to his home district of Ka'u that part of his army, passing near the summit of Kilauea volcano, was suffocated during a rare explosive eruption a signal to many observers that the gods favored Kamehameha. Although weakened psychologically as well as physically by this tragedy, Keoua remained tenacious and managed to hold his own against Kamehameha's forces for several more months.

c) Kamehameha is Instructed to Build a Heiau Meanwhile, from Moloka'i, Kamehameha had sent his aunt to Kaua'i to consult a kahuna as to what the future course of his actions should be in order to take possession of Hawai'i and the rest of the islands. Instead, she found on O'ahu the famous prophet of Kaua'iKapoukahi. This man., who according to the historian John Papa I'i was skilled in selecting propitious sites for heiau, told Kamehameha that if he rebuilt the temple at Pu'ukohola ("hill of the whale") near Kawaihae and rededicated it to honor Ku-ka'ili-moku, he could conquer the rest of the islands. Kapoukahi supposedly prophesied that "War shall cease on Hawaii when one shall come and shall be laid above on the altar (lele) of Pu'u-kohola, the house of god." A few sources state that construction of this heiau had been an intention of Kamehameha for some time. Kamaka Paea Kealii Ai'a writes that "From time to time the High Priest of Kohala urged Tamaahmaah to build a heiau at Puukohola, Kawaihae, for which he would gain supremacy of Hawaii." The Reverend Herbert Gowen states that Kamehameha had promised to build it [heiau of Pu'ukohola] years before this, but had evidently been trying carnal weapons first and leaving spiritual means as a kind of last resource." One part of the legend also states that Kamehameha first intended to refurbish and rededicate Mailekini temple, on the slope below Pu'ukohola. But Kapoukahi, who had joined Kamehameha's staff as royal architect, suggested that a new temple on the summit would be more appropriate and provide greater benefits. According to Thomas Thrum, Kapoukahi instructed Kamehameha "to build a large heiau for his god at Puukohola, adjoining the old heiau of Mailekini. . . . Thrum continues:

Only archeological excavations could provide definitive evidence on whether Pu'ukohola Heiau is a new structure or a renovation of an older, abandoned temple. According to Hawaiian mythology, the original temple of Pu'ukohola was consecrated by the god Lono about 1580. Fornander gathered some data on this subject from native accounts:

Fornander states that the long years of warfare and strife were becoming tiring to Kamehameha, who "stood no nearer to the supremacy of Hawaii than he did on the day of Mokuohai." Because neither spears nor guns had succeeded in annihilating Keoua, Kamehameha decided to follow the seer's advice "and the construction of the Heiau on Puukohola was resumed with a vigour and zeal quickened, perhaps, by a consciousness of neglected duty."

d) Construction of the Heiau Begins According to Samuel Kamakau, Kamehameha

According to Historian Kuykendall, basing his information on Kamakau and Fornander, in 1790

Fornander states that an aged informant from Kawaihae had actually helped carry stones for the construction of Pu'ukohola Heiau. This man painted a vivid picture of thousands of people encamped on the hillsides and described the careful regulation of their eating periods, work shifts, and break times. He also mentioned the large number of chiefs present and the numerous human sacrifices required at various stages of construction.

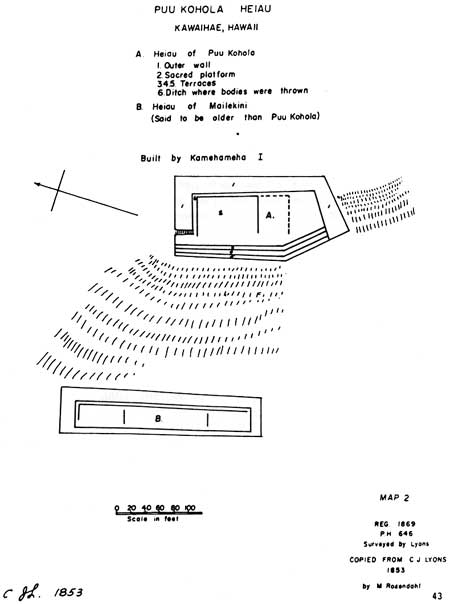

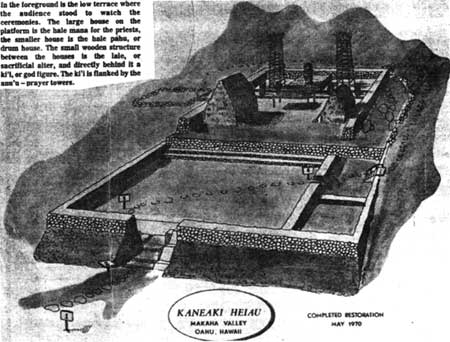

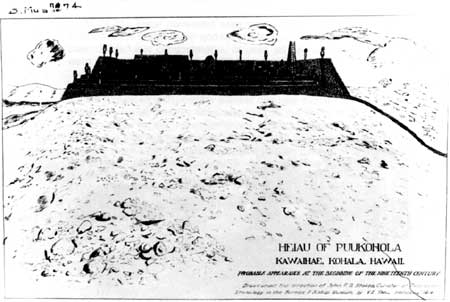

e) Warfare Interrupts Construction A revolt on the islands of Maui, Lana'i, and Moloka'i, followed by an invasion of North Kohala by the previously conquered chiefs of those islands, interrupted work on Pu'ukohola Heiau. Possibly the news that Kamehameha was building a major temple unsettled his rivals to such an extent that they hoped that even if they could not kill the ambitious chief, they could at least keep the temple from being ritually perfect by interfering with its erection and the attendant ceremonies. If the construction process displeased Ku-ka'ili-moku, Kamehameha's foes reasoned, it might eliminate or reduce the spiritual power exuded by the heiau. A sea battle in 1791 near Waipi'o Valley raged, with both Kamehameha and his foes utilizing muskets and cannons operated by foreigners. Kamehameha's fleet included, in addition to double canoes armed with cannons, his warship Fair American. Young and Davis commanded his artillery. This battle of Kepuwaha'ula'ula, or "the red-mouthed gun," referring to the repeated firing of cannons and muskets as well as possibly to the carnage, resulted in defeat of the invading forces. Apple states that this was Hawai'i's "first and last real sea battle using Hawaiian canoes and Western gunpowder." f) Kamehameha Becomes Undisputed Ruler of Hawai'i Island Kamehameha then resumed construction of his heiau, a massive terraced and walled hilltop platform built of mortarless, waterworn lava rocks and boulders. Measuring about 224 by 100 feet, it contained walls on each end and the landward side. The side toward the sea remained open. Three narrow, terraced steps down the hillside to the west enabled the interior to be seen from the sea. The temple was finished in the summer of 1791. It has been written that Keoua was enticed to the dedication of Pu'ukohola Heiau by a ruse, in the belief that he and Kamehameha were to arrange a treaty of peace. Given the past history of the two men, however, it is hard to believe that Keoua would have considered this a possibility. Keoua and his retinue proceeded to Kawaihae amidst considerable pomp and pageantry. According to legend, the journey had "the appearance of a fatalistic resignation to the doom which he clearly recognized as a possible issue of his journey to Kawaihae." Samuel Kamakau relates that

Keoua placed the reminder of his companions in a canoe with his younger brother Kaoleioku. Kamehameha, resplendent in feather cloak and helmet, stood on the shore below the heiau to greet his visitors. Versions differ as to what happened next, but at some point, while Keoua was disembarking, someone among Kamehameha's retainers killed him and the others in his canoe; Kamehameha did, however, prevent the killing of Kaoleioku and others in the party. Fornander states that prior to Keoua's arrival, "the umu had been prepared and was red hot. Keoua was then roasted" before he and the other victims were offered up as sacrifices to celebrate this great victory. Many questions have been raised as to why Keoua willingly entered the camp of so bitter an enemy. Fornander believed that the defeat of Kamehameha's enemies in the battle of Kepuwaha'ula'ula probably influenced Keoua to try to negotiate with Kamehameha. Perhaps Keoua realized the political and religious significance of this heiau and surmised that with its completion his fate was sealed. Whether his death occurred by or against Kamehameha's wishes is also disputed. After critically examining the statements of a variety of early native and foreign writers on the subject, Fornander concludes that

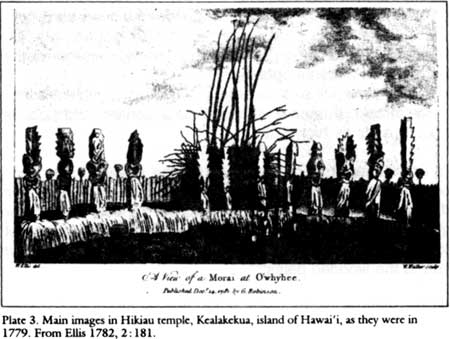

g) Kamehameha Unites the Hawaiian Islands Whether planned or not, the assassination of Keoua gave Kamehameha undisputed control of Hawai'i Island by 1792. In early 1795 Kamehameha took Maui, Lana'i, and Moloka'i. With the conquest of O'ahu that year, Kamehameha's aggressive military policy succeeded in bringing all the islands but Kaua'i under his control. In 1810 that island's paramount chief acknowledged Kamehameha's supremacy, completing the consolidation of the islands into the Kingdom of Hawai'i, which Kamehameha ruled until 1819 and his descendants until 1872. Although the monarchy was overthrown in favor of a republic in 1894, it established the foundation for the future state of Hawai'i. B. Pu'ukohola Heiau (continued) 2. Historical Descriptions a) Introductory Remarks Considering that there were foreigners in the vicinity, and that the construction process for Pu'ukohola Heiau must have been quite impressive in terms of the number of people and the rituals involved, the paucity of firsthand accounts of this event or of the structure's appearance at the time of construction is disappointing. Because this was considered a very sacred temple, however, there really existed no opportunity for detailed Western observances until after the abolition of the kapu system. b) Archibald Menzies, 1792-94 The first Western account we have of Pu'ukohola Heiau is that of Archibald Menzies of the Vancouver expedition. It is important because he viewed the structure soon after its construction while it was still being used for ceremonial purposes and thus was still regarded with fear by the common people:

Although it is difficult to understand how Menzies could describe this as a "little" temple, his description is probably a good indication of the heiau's original appearance. Note that he does not mention wooden images, which were usually an integral part of the furnishings of a luakini and the carving and erection of which have been described in the accounts of this temple's construction. Because during this time Kamehameha was still in the process of reconquering and subjugating the other Hawaiian Islands, it would appear that the twelve skulls of those who dared oppose him were being displayed as a warning to others and as a sign of Kamehameha's patronage in military matters by Ku-ka'ili-moku. c) Samuel Patterson, 1804-5 The next description, although scanty in comparison, is by the American seaman Samuel Patterson, who chronicled his travels in a merchantman during the period 1800 to 1817. He noted about 1804 that the Hawaiians

What sort of "roof" Patterson is referring to is unclear, although presumably he simply means that the skulls were positioned on the platform or on the walls surrounding the platform area. d) Otto von Kotzebue, 1816-17 During 1816-17, Otto von Kotzebue, commander of the Rurick, led a Russian expedition in search of a northeast passage that visited Hawai'i in the course of its travels. His description of Kawaihae Bay adds little, except to note that "We saw here several morais, which belong to the chiefs of these parts, and may be recognized by the stone fence, and the idols placed in them." e) Louis de Freycinet, 1819 In 1819 an official French scientific and political expedition commanded by Captain Louis de Freycinet visited the islands shortly after the death of King Kamehameha. Jacques Arago, the ship's artist, left a very descriptive journal which is highly useful for some types of information:

This indicates that Pu'ukohola Heiau was used regularly up through Kamehameha's lifetime for religious services and that human sacrifices were a part of those services. Sometime between 1804 and 1819, it appears, the skulls of Keoua and his followers were removed and the customary wooden images became the dominating feature. This might have occurred around 1810 when the chief of Kaua'i acknowledged Kamehameha as supreme ruler, completing the formation of the island kingdom. At that time the warning symbolized by the skulls and the warlike atmosphere they generated would no longer have been necessary.

f) Missionaries Hiram Bingham, Henry Cheever, 1820 In 1820 Protestant missionaries arrived in Hawai'i on board the brig Thaddeus. They landed first in Kawaihae, knowing that was one of the favorite residences of King Kamehameha as well as the home of John Young, known to all sea captains as one of the king's trusted and very influential advisors someone whom it would pay to have on their side. Learning upon their arrival of the death of Kamehameha and the abolition of the old religion, the missionaries were eager to proceed to Kailua for an audience with the new king. During their brief stay in Kawaihae, however, they had time to briefly reconnoiter. Missionary Hiram Bingham stated that:

This description is also found in a journal of the Sandwich Island mission begun on board ship and possibly co-authored by Bingham, who adds in that document that the terraces "made convenient places for hundreds of worshipers [sic] to stand while the priest was within offering prayers and sacrifices of abomination." Whether Bingham was told that people stood on the terraces during services or simply assumed that the terraces were used in that way is unknown. He continues:

According to this account, therefore, Pu'ukohola Heiau was destroyed and abandoned at the time of the abolition of the kapu system by Liholiho just as were others throughout the islands. This account also suggests that Mailekini was not the scene of human sacrifices. Despite Pu'ukohola Heiau's significant personal importance to Kamehameha, it would seem that his son did not view it with any particularly strong attachment, and certainly the usefulness of the heiau was over. However, when Liholiho returned to Kawaihae after the death of his father, he reportedly reconsecrated the heiau at Puukohola, following the traditional method of announcing one's new role as leader. Missionary Henry Cheever, sailing by the west coast of Hawai'i Island, mentioned: "We passed in the afternoon the Bay of Kawaihae, and saw the huge heiau which Kamehameha II. went to consecrate at the death of his father. . . " Because this was the structure that supposedly provided Kamehameha with the power to become king, perhaps this ritual was seen as necessary to pass on the former ruler's power to his son. Marion Kelly speaks of Kawaihae as "the place where Kamehameha II returned after the death of his father to seek consolidation of his forces and consecration of his leadership role." Kawaihae and Pu'ukohola Heiau appear to have retained some of their former spiritual and political significance at least immediately following Kamehameha's death, but having performed this last service in sanctifying Liholiho's role as king, the heiau structures were destroyed with the abolition of the kapu system. g) Reverend William Ellis, 1823 The account of Pu'ukohola Heiau considered the most informative of these early sources is that by the Reverend William Ellis. Although very lengthy, it is presented here in its entirely because of the wealth of construction details. Much of the data on ritual ceremonies and procedures interspersed with the physical description was probably supplied by Ellis's native guides, who should have had a good knowledge of what went on at the site in more recent times. William Ellis was part of a delegation of Honolulu missionaries that made a tour of the island in 1823 to look for suitable locations for mission stations. Others in the group included Asa Thurston, Artemas Bishop, and Joseph Goodrich. While staying at Kawaihae, Ellis visited the temple of Pu'ukohola:

h) Reverend Artemas Bishop, 1826 In November 1826 the queen regent Ka'ahumanu, residing on O'ahu, visited the island of Hawai'i for about two months. The Reverend Artemas Bishop accompanied her when she stopped at Kawaihae:

i) John Kirk Townsend, 1834-37 John Kirk Townsend, an American ornithologist, embarked on a journey that included Hawai'i during the years 1834-37. Anchoring off Kawaihae, he went ashore, visited John Young's widow, and also took a look at Pu'ukohola Heiau. He noted, probably based on local information, that it had not been used as a temple since the abolition of the kapu system:

Townsend states that victims were sacrificed on this platform, "the gods standing around outside in niches made for their accommodation." j) James Jarves, 1837-42 James Jarves published a history of the Hawaiian Islands in 1843 in which he described Pu'ukohola as being

k) Gorham D. Gilman, 1844-45 Gorham D. Gilman, in his journal of a trip to Hawai'i during 1844-45, visited Kawaihae and

l) Account, 1847 In June 1847 a party of men voyaged to Hawai'i to visit Kilauea caldera. On the way they landed in Kawaihae Bay:

This is the first mention of an underground passage on Puukohola, although it possibly simply refers to a lower walkway or passage in the platform area or along the east wall that some observers mistook for an underground passage that had formerly been covered over. m) Samuel S. Hill, 1848 Samuel S. Hill, English author and traveler, arrived in Hawai'i on the Josephine in 1848 and visited Kawaihae's archeological sites:

This account seems to suggest that a large number of worshippers could be found in the temple during certain rites. Whether or not these attendees spilled over onto the terraces is not known, although the missionary accounts presented earlier also mentioned this possibility. This account also suggests low standing walls within the interior dividing the platform into separate areas used either for ritual purposes or for priests' quarters. n) Charles-Victor Crosnier de Varigny, 1855 Charles de Varigny provides what he states is an account of a visit to Pu'ukohola Heiau in 1855, but one needs to be careful in reading it because he confuses several bits of data with the construction of Mo'okini Heiau in northern Kohala. He states that the heiau about a mile from Kawaihae "is the largest and most intact still in existence in the archipelago. Its length is 350 feet, its width 150. The walls are 50 feet thick at the base, 8 at the top, and not more than 20 high." He continues,

o) Lady Jane Franklin, 1861 Lady Franklin, widow of the renowned Arctic explorer Admiral Sir John Franklin, visiting Kawaihae in 1861, went to see Pu'ukohola Heiau and described it as

This certainly provides an explanation for the three terrace levels, but again it is difficult to know whether this information is accurate. The grandson of Isaac Davis accompanied Lady Franklin on this visit to the heiau, but whether he supplied the details on its construction and use is unclear. p) Clara K. Whelden, 1864 The wife of the master of the whaling bark John Howland, out of New Bedford, Massachusetts, passed through Kawaihae Bay in 1864, but noted only that

q) Isabella Bird, 1873 Isabella Bird, traveling in Hawai'i in 1873 for her health, so benefitted from the climate that she stayed for nearly seven months. During that time she traveled around on horseback exploring local sites. Her description of Kawaihae was quoted earlier, but she also visited the nearby heiau on Puukohola, which stood "gaunt and desolate in the thin red air," entering it through a narrow passage between two high walls. Describing the structure as an irregular parallelogram, 224 feet long and 100 feet wide, she added that

Much of this information was probably gained from Mrs. Bishop's companions and merely repeats the interior arrangement described by Ellis and other earlier visitors. Whatever fact it was originally based on, the information had been passed down that the temple terraces were for the accommodation of observers of the ceremonies within.

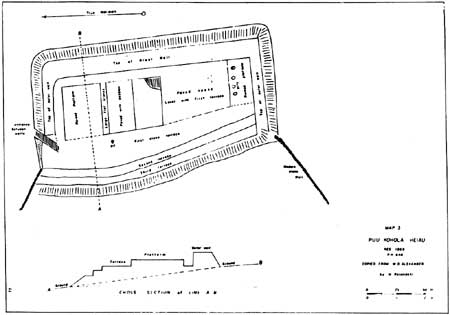

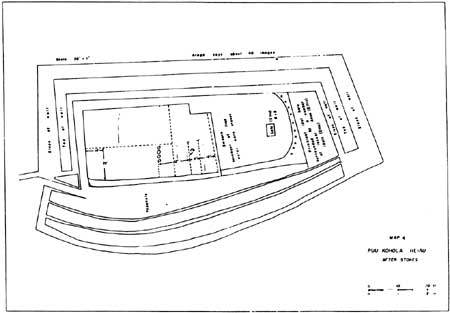

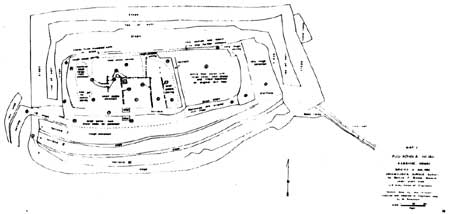

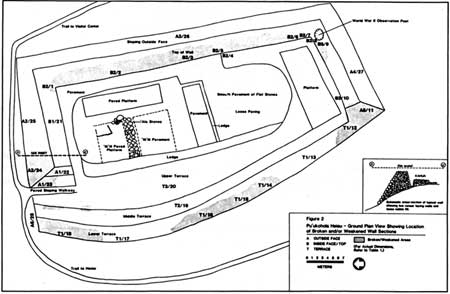

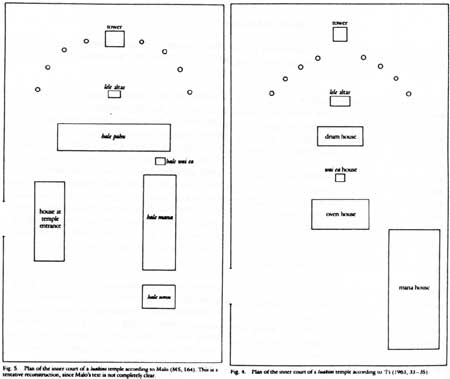

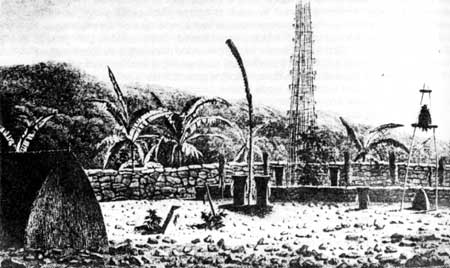

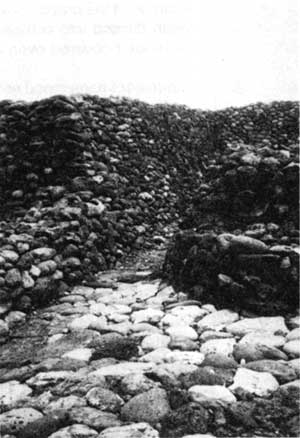

r) Frank Vincent, Jr., ca. 1875 Traveler Frank Vincent, Jr., mentioned Pu'ukohola Heiau in his 1870s travelogue but provided nothing new in terms of a description. He did state that "Human sacrifices were offered in this temple as recently as the early part of the present century" a fact he was undoubtedly told by local residents. However, that observation seems to be corroborated by Jacque Arago's statement that human sacrifices were practiced as late as 1809. s) John F. G. Stokes, 1906 In 1906 the Bishop Museum of Honolulu sent John F. G. Stokes to Hawai'i Island to conduct archeological research on temple remains. The work was part of a research design for Hawaiian archeology, focusing on recording and making plan drawings of temple structures on the various islands to document changes in construction style. Stokes noted that Pu'ukohola Heiau incorporated terrace, platform, and wall features, all with a partial veneer of ala, or waterworn stones. The walls on the north, east, and south were composed entirely of slightly rounded ala, while their narrow upper surfaces were paved with flat ala. The terraces to the west were filled in with rough stone like that found nearby, but faced with rounded ala and paved with flat ala. "Choicer" stones had been used for the large area of low pavement just to the south of the middle of the heiau. A large platform containing several divisions, suggesting house sites, occupied about one-third of the interior in the northeast quarter of the structure, rising about 4-1/2 feet above the floor. It was faced with ala stones and roughly paved with stones on the east and south; smooth coral fragments covered the northwest half. In the middle of the platform, leading in from the west, was a roadway of flat ala, two stones wide, ending in a single large ala convex on its upper surface. A ledge 2 feet high and 2-1/2 feet wide ran around the west side and south end of this platform. Another platform at the southern end of the heiau stood three feet high; also paved with ala stones, it appeared to have been disturbed. Five pits existed in the platform, one in the southeast corner and the others forming a rough line near and parallel to the northern face of that platform. A local informant told Stokes the pit to the west was the lua pa'u and the lele had stood near it, on the western edge of the platform. Stokes was not sure, however, if these were ancient or modern pits because of the amount of disturbance. Below this last platform and the low, smooth pavement described earlier, Stokes found a heap of loose stones in a sort of crescent form, which he did not think had been a later intrusion. On the eastern edge of the highest terrace to the west lay a strip of earth five feet wide, only a few inches below the level of the terrace pavement. Passages north and east of the main interior platform, between it and the outer walls, had been filled in by fallen stones. He did not think these had originally been paved. The entrance to the top of the heiau was over a stone pavement inclining upward and to the south-southwest. East of the entrance a bench had been built into the slope of the west end of the northern wall, about 2-1/2 feet above the terrace pavement a niche for a "guardian idol" he ventured. The heiau was constructed so that, although the west side was open, one could not get a close view of interior proceedings from the outside. According to local information, Stokes noted, the smooth ala pavement was for dancing; also, a stone idol used to stand on the middle terrace and a wooden one on the lower terrace. Stokes also mentioned that an elderly local native had told him that the body of Keoua had been cooked in an underground oven located on a ridge about fifty feet west of the northwest corner of Pu'ukohola Heiau. In another group of notes, Stokes described the two small walls stretching from the corners of Pu'ukohola to the southwest and northwest, the latter beginning just east of the entrance. He suggested these delineated the limits of the sacred ground connected with the temple in ancient times. In other miscellaneous information, he noted that the terraces, three in number, bulged outward, following the contours of the ground. The lower two were narrow, but the upper one broadened out as the main floor of the heiau. He also said that small idols had been found hidden within the structure and conjectured that the pits in the south end could have resulted from digging for other hidden statues. But he believed that the four pits arranged in a line could have been enlargements of holes for large idols. Stokes's plan of Pu'ukohola Heiau placed the 'anu'u and lele according to Ellis's description. The site of the drum, or king's house, he placed on the south projection of the main platform. He also inserted other traditional temple structures, such as the hale mana, waiea, hale umu, and guardhouse. The large, long mana he placed on the east side of the platform, with the stone path leading to it. He added a wooden fence on the upper terrace, believing this explained the strip of earth and loose stones dividing the upper terrace lengthwise. This fence would help define the limits of the sacred portions of the temple, a necessity if there were ali'i or commoners standing on these terraces. Perhaps this is the fence on which Kamehameha displayed the skulls of Keoua and his followers.

t) Thomas Thrum, 1908 Thomas Thrum, in his Hawaiian Annual for 1908, states that

u) Gerard Fowke, 1922 Gerard Fowke, representing the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., performed some archeological work in Hawai'i in 1922, during the course of which he examined Pu'ukohola Heiau. Not much new information was gleaned from his reconnaissance, however:

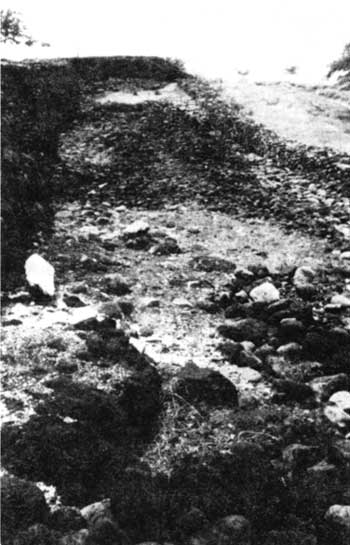

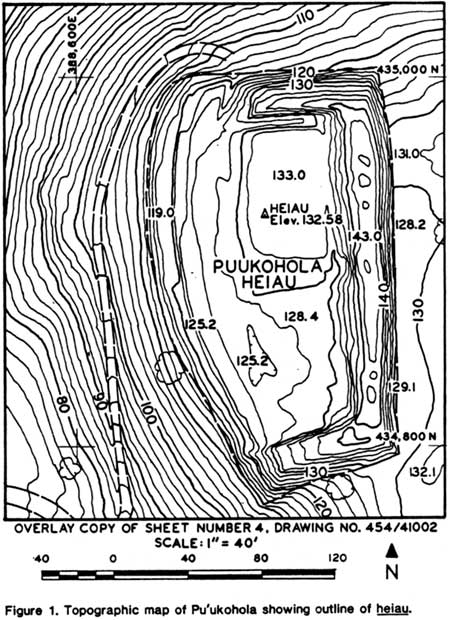

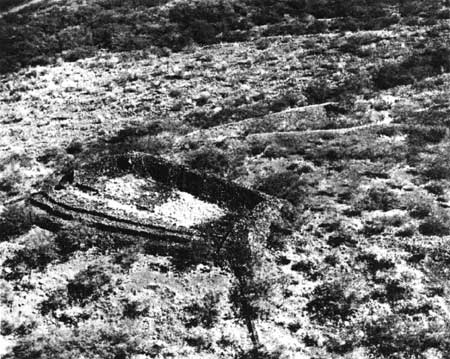

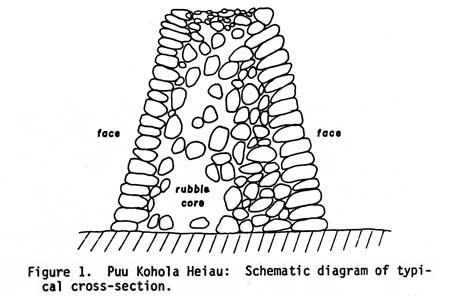

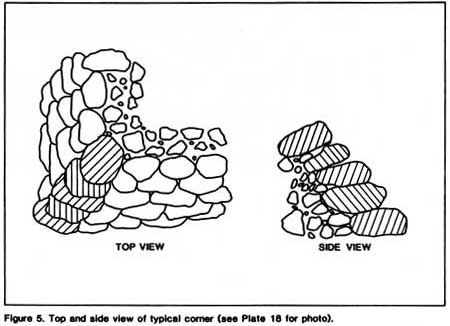

v) Oral Interview, 1919-20 These are the few historical accounts of Pu'ukohola Heiau that provide any type of detailed description of the structure. In addition, an oral interview between Rose Fujimori and Solomon Akau mentions a large A-frame of a former grass house facing the ocean, with a door facing sideways, on top of the heiau on the 'ili'ili ca. 1919-20. Nothing of its origin or use is known, but it was certainly a later addition that might account for some of the disturbance noted by Stokes. 3. Modern Description In 1969 the Bernice P. Bishop Museum in Honolulu, at the request of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, conducted a detailed archeological survey of Pu'ukohola and Mailekini heiau prior to proposed construction work on the Kawaihae small boat harbor. This resulted in feature documentation that was published in the Hawaii State Archaeological Journal 69-3. Because of the length of the description of Pu'ukohola Heiau, the reader is referred to that work. Between 1975 and 1979, Edmund J. Ladd, NPS Pacific Area Office archeologist, supervised emergency stabilization activities on the heiau. No archeological excavations were undertaken, but the site was mapped and observations on prehistoric construction techniques recorded. From the descriptions of Pu'ukohola and Mailekini heiau through the years, it is apparent that little if any preservation work has been done on them, at least formally. In 1928 the "Sons of Kamehameha, a now defunct organization, are thought to have partially restored segments of the central platform and courtyard areas in honor of the sesquicentennial celebration of the European arrival in the Hawaiian Islands, but that work was not documented. The records show little change in the structures, however. The question of how often they were used during Kamehameha's time and how long after the abolition of the kapu system will be addressed in the Analysis and Recommendations Section later in this report. It appears, however, that little local repair work was done and perhaps was not really needed because of the sturdy initial construction. The majority of the grass structures on top of Pu'ukohola were destroyed around 1819 according to historical accounts, and any that escaped the conflagration would have deteriorated quickly with disuse. It would appear that the temples, after abandonment, were little visited except for occasional sightseers and probably local residents who might have continued limited veneration of the area. By the time Pu'ukohola Heiau came into NPS hands in 1972, some portions of the interior back wall had collapsed. A year later a large section on the northwest, above the entrance onto the platform, also collapsed, in addition to a smaller segment on the southeast wall. The construction method used on Pu'ukohola Heiau was characteristic of early Hawaiian architecture, involving stacking stones

The integrity of the structure has been impaired over the years due to natural deterioration, earthquake activity, vibrations, rain and wind erosion, and human visitation. Weaknesses in the structure are caused by the material used, consisting of rounded boulders, some of which are very large, some small, some waterworn, some angular; the topography, which consists of the brow of a rounded ridge; and the method of construction outlined above, involving stacking of rocks with no mortar.

Following are excerpts from Edmund Ladd's 1975 description of Pu'ukohola Heiau:

During stabilization work, Ladd found a pit on top of a wall that he surmised served as a coastal observation post during World War II. It had been connected, via field telephone lines buried along the top of the heiau walls, with foxholes and gun emplacements on the beach south of Mailekini Heiau. The lines and the lumber used to line the observation pit were removed and the pit infilled with stones. All major broken areas of Pu'ukohola were cleared, stabilized, and restored during this project. The structure stands today as it was described by many early visitors, consisting only of a massive temple platform surrounded on three sides by high walls with descending terraces toward the sea. The pole and thatch structures that were noted historically in the temple area are gone. Wing walls extend toward the sea from the northwest and southwest corners. Occasional offerings are still made here. C. Mailekini Heiau 1. Traditional Construction History Little is known of Mailekini Heiau, located on the slope between Pu'ukohola Heiau and the coast. Similar in construction to that of Puukohola, with massive stone walls inland and open to the sea on the west, it is, however, smaller in size. Archeologist Edmund J. Ladd stated that Mailekini temple site is an older site probably representing the inter-chiefdom and inter-district or island warfare of the period prior to 1790. It is a temple site undoubtedly built by the district ruling chief." It is in connection with one of the early South Kohala chiefs that the heiau is mentioned in the early literature, as the location where the aging Alapa'inui, governing Kohala about 1760, conducted ceremonies transferring his rule and lands to his son Keawe'opala. As mentioned previously, several authors believe that Kamehameha first began restoring Mailekini in response to Kapoukahi's prophesy, but later moved work higher up the hill. Dwarfed by the magnificent structure looming over it from above, Mailekini Heiau was little noticed and only briefly mentioned, if at all, by visitors in the historical period. Whether it was functioning up until the time of Kamehameha's construction of the present Pu'ukohola Heiau is unclear, although early references seem to indicate that it was already abandoned and unused by that time. Isaac Iselin, supercargo on the Maryland, at Kawaihae in 1807, mentioned noticing "two remarkable 'morays,' built by Tamaahmaah during his two years' stay at this place. . . ." This could have been merely an assumption on his part or might suggest that Kamehameha I had performed some work on Mailekini, although it is fairly certain that it had been originally constructed long before.

2. Mailekini Becomes a Fort Although Kamehameha's rule over the Hawaiian islands seemed secure, his major rivals having been killed or thoroughly subjected, he was undoubtedly aware that threats to his power could arise at any moment. In addition, the increasing presence of Europeans might have made him uneasy and mindful of the vigilance he would need to keep both his subjects and arriving foreigners in line. Influenced by his exposure to European military strategy and Western weapons of destruction, Kamehameha decided to build forts with mounted guns to protect his major ports. Reinforced by a navy, these safeguards would hopefully ensure the longevity of his reign. De Freycinet noted that

About 1812, Kamehameha sent cannons, obtained from traders, to Kawaihae Bay to be mounted under the charge of John Young. Marion Kelly notes that about 1816, Gov. John Adams transported seven guns from Kawaihae to Oahu, probably for the use of the fort there. Apple states that by 1819 Young had installed twenty-one ship's guns on the foundations of Mailekini Heiau, where they guarded the king's residence nearby as well as the harbor. As de Freycinet neared the anchorage of Kawaihae on his journey in August of that year, he "saluted the Sandwich Islands flag with eleven guns, which were answered in equal number by a battery mounted on shore near the royal residence." The exact number of guns on the heiau is unclear. De Freycinet says later that, upon landing to pay his respects to King Kamehameha on the beach, he "advanced in the direction of the King, who grasped my hand with cordiality and told me, through M. Rives, that he would salute me with seven guns."

Jacques Arago also talked about Mailekini Heaiu, stating that

This description implies that some type of construction work was involved in setting up this "fort," although the extent of these modifications is unclear. According to Arago, the fortifications at Kamakahonu in Kailua consisted of "twenty odd guns of small caliber, protected by casemates, or sheds covered with coconut leaves." The Reverend William Ellis described the ruined heiau of Ahu'ena at Kailua in 1823, noting that after the abolition of the kapu system, the governor converted the structure into a fort by widening the stone wall next to the sea and placing cannon on it. When guns were added to Mailekini Heiau, its religious functions moved to a nearby enclosure in the Pelekane area. Arago noted that

The extent of the garrison at Kawaihae is unclear. Arago describes the fortifications at Kamakahonu, stating they were manned by five or six warriors, without uniforms and carrying guns on their shoulders, whose sentry duty consisted of pacing from one end of the fortifications to the other. Their "tour of duty" lasted fifteen minutes. Kamehameha had a good-sized military contingent at Kawaihae, according to de Freycinet:

Some of the king's soldiers must have been manning the fort in order to fire the salute to de Freycinet. 3. Historical Descriptions a) Reverend William Ellis, 1823 In 1823 the Reverend William Ellis, after viewing Puukohola,

No explanation is provided for his assumption that there had once been many idols at Mailekini Heiau. If taken literally, his description implies that there was some physical evidence of this, either in the form of numerous niches or of a few remaining images. It is interesting to note that Ellis stated in regard to Ahu'ena Heiau in 1823:

The relationship between Mailekini, Puukohola, and Hale-o-Kapuni heiau is unclear, either in terms of a physical or ceremonial connection. Whether human sacrifices took place at Mailekini in the pre-European contact period is unknown. Perhaps Mailekini was in some way connected with the shark heiau, with human sacrifices being made at Mailekini and the bodies then being deposited in the water for the sharks to devour. Hale-o-Kapuni appears also to be an ancient structure. Hawaiian mythology as recorded by Fornander and presented in the section on Pu'ukohola history indicates that a heiau on Pu'ukohola was the site of a sacrifice during the time of Lonoikamakahiki. It is generally assumed that this refers to a heiau on top of the hill predating the present one rather than to Mailekini. Possibly Mailekini, if not actually used for human sacrifices itself, was connected in some way with rituals at the temple on the hill. b) John Kirk Townsend, 1834-37 John Kirk Townsend, a naturalist visiting Hawai'i between 1834 and 1837 collecting natural history specimens, also stopped to see Pu'ukohola and Mailekini. He described the latter as the place to which the bodies of dead chiefs were carried prior to interment. There they lay in state for a certain period of time, according to their rank, before their flesh was stripped off and tossed into the sea and their bones deposited in caves or subterranean vaults. Presumably he was told this by a native guide or other local informant. 4. Later Descriptions a) John F. G. Stokes, 1906 Stokes described Mailekini as being probably older than Pu'ukohola and affected by more internal changes, particularly recent burials in the north end of the interior. b) Thomas Thrum, 1908 In his Hawaiian Annual for 1908, in which he compiled a list of heiau sites throughout the Hawaiian Islands, Thomas Thrum described Mailekini as being 270 by 65 feet in size, with a low perpendicular wall in front, a heavier, sloping one in back, and no internal features except graves. Little is known about these graves that appear to have been added around the turn of the century. Located primarily at the northern end of the interior area, many have been disturbed, possibly due to exhumation of remains for reinterment elsewhere. A local resident, Solomon Akau, remembered going to Mailekini in the early 1920s with his great-grandmother to decorate a grave, although he did not know whose it was. c) Deborah Cluff et al., 1969 Although Lyons mapped Mailekini Heiau in 1853, the only detailed description and mapping of its features is presented by Cluff et al. as a result of their 1969 survey work prior to construction of the Kawaihae small boat harbor. Their observations in full may be found in that document; the following general remarks are taken from their work:

Eleven possible grave sites not shown on Lyons's 1853 survey but noted by Stokes in 1906 were documented during this survey within the temple platform area two in the southern section, three in the central portion, and six in the northern section. The contents of two of the burial chambers had been removed, either through vandalism or for reburial. Both features contained wooden coffin fragments. The characteristics of all grave features indicated late use (historic period) of the heiau by local residents as a burial ground:

D. Hale-o-Kapuni Heiau 1. Shark Heiau Submerged just offshore below Mailekini Heiau are the ruins of what is believed to have been another temple, which local lore relates was dedicated to the shark gods. The ancient Hawaiians believed in animal helpers and protectors, half god and half human, who relayed their counsels through the lips of some medium who became for the moment possessed by their spirit. These 'aumakua were served and worshipped by particular families, this duty being passed down through the generations. Martha Beckwith points out that "On the coast, sharks are the particular object selected for veneration." In her discussion of 'aumakua, Beckwith states that sometimes specific individuals are worshiped, such as particular sharks that are recognized as individuals and are expected to calm the seas or provide bountiful catches for their keeper, and sometimes all the species of a class are venerated as being representative of the 'aumakua. She quotes Joseph S. Emerson as saying that each locality along the coast of the islands had a "special patron shark whose name, history, place of abode, and appearance were well known to all frequenters of that coast." Shark gods were invoked with specific prayers, and temples were erected for their worship. According to Emerson there were several well-known shark gods worshiped at various places in the islands. Among these were Uukanipo, two great sharks who were twin brothers, and another called Kaaipai, all of whom lived at Kawaihae. The first two lived at Kamani and were regularly fed. When the king wished to see them, their keeper hung two bowls of 'awa from a forked stick to attract them. Kaaipai was kept by a couple living at Puako in Kawaihae who often went hungry because the taro plant did not grow there. Their shark would capsize boats carrying food and take the cargo to his cave. He would then appear in a dream to the couple and tell them where to find it.

2. Historical Descriptions a) Abraham Fornander Fornander mentions Hale-o-Kapuni in connection with the legend of Lonoikamakahiki's battles as being a camping spot "immediately below the temple of Pu'ukohola and Mailekini at Kawaihae." b) Theophilus Davies, 1859 Theophilus Davies arrived off Kawaihae in 1859, passing in the water beneath a "sacred enclosure" about twenty yards square and formed by a massive stone fence five feet high (probably Mailekini Heiau). A large stone formed its altar, he said,

The reader assumes from this description that Davies actually saw a pile of rocks in the water. This heiau is identified on Jackson's 1883 map. c) Oral Tradition The presence of Hale-o-Kapuni is well known to local inhabitants:

An informant pointed out to Marion Kelly the location of the heiau structure, now covered by silt washed off the coral stockpile area nearby. Anthropologist Lloyd Soehren stated that, as children, older residents of the area remembered seeing the heiau rising about two feet above the water. One person remembered a channel leading into a larger area within the temple where the bodies were placed for the sharks. This area is known to be frequented by sharks, perhaps as a result of having been lured there in ancient times. This heiau has never been located or documented through underwater archeology. Tidal wave activity and the silting resulting from harbor construction activities have covered any features in this area. One Kawaihae informant stated that during World War II, amphibious equipment landed in the water and on the beach and may have obscured or scattered remains of the heiau. E. Stone Leaning Post (Leaning Rock of Alapa'i, Alapai'i's Chair, Kamehameha's Chair) Pohaku o Alapai ku palupalu mano, "the rock of the chief named Alapai of the one who puts the human shark bait out," originally stood in the shade of a large keawe tree on the shore below Mailekini Heiau. Historian Russell Apple has stated the object was actually more of a leaning rock because the early Hawaiians did not sit in chairs as Europeans do but sat on the ground. The stone was set into a concrete footing in 1935; a truck that backed into it in 1937 broke off the top. It was restored by the Waimea Hawaiian Civic Club for the dedication of the national historic site in 1972. During that process, the rock was moved more into the open but farther back from the sea. It is now in three pieces and stands on a foundation. One early account said that King Kamehameha sat there while his staff compiled the tally of the latest fishing expeditions, and that somewhere near the stone might have been the spot of Keoua's murder. Apple states that although referred to as Kamehameha's Chair, the rock is by local tradition more closely associated with one of Kamehameha's staff chiefs named Alapai Kupalupalu Mano who liked to use human flesh for shark bait and watched from this point as sharks entered Hale-o-Kapuni to devour the food offerings put out for them. Apple points out that the rock's location would be ideal for observing activities in the water around the heiau. He also notes that catching sharks was a sport indulged in by high chiefs and conjectured that perhaps the animals were conditioned to rotten flesh in the offshore temple so that they could be enticed with it into the deeper water and easily noosed. F. Pelekane (King's Residence) 1. Significance "Pelekane" refers to the ancient royal compound on the shoreline immediately northwest of Mailekini Heiau. The word is a Hawaiianization of "Britain" or "British," and according to some Hawaiian informants the name was given to the area because it was thought that John Young and Isaac Davis murdered the high chief Keoua here as he landed on the shore below Mailekini Heiau for the dedication of Pu'ukohola Heiau. The area consisted of the royal residence and probably some housing for other members of the nobility that comprised the royal court. It is important then, not only as the residential site for generations of Big Island ruling chiefs, but as the site of the murder of Keoua and Kamehameha's assumption of the kingship of the Hawaiian Islands. It was reportedly here that Liholiho agreed to share the profits of the sandalwood trade with his high chiefs if they would agree to his ascension to the throne.

2. Historical Descriptions a) Louis de Freycinet, 1819 Pelekane was also the landing spot for foreign ships, such as de Freycinet's, during the European contact period. De Freycinet visited the new king, Liholiho, in residence at Kawaihae after his father's death. He described the royal house as

b) Jacques Arago, 1819 Jacques Arago was less generous in his description of the same:

c) Madame de Freycinet, 1819 Madame de Freycinet, who accompanied her husband on his journey, kept a journal as well as writing many letters about their experiences. She briefly describes some of the other structures in the royal complex at Kawaihae, first noting that the king

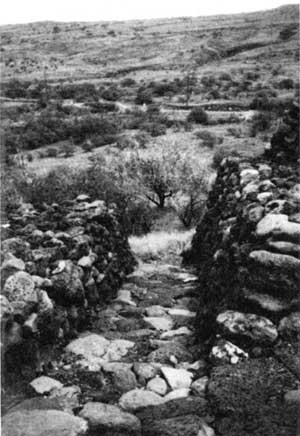

d) L. I. Duperrey, 1819 L.I. Duperrey of the de Freycinet expedition drew the king's residence and related structures on the beach, even showing the lanai or "light shed" under which the king's wives reposed. These structures are referred to as "Maisons du Roi" in the compound area shown on his map "Plan de la Baie de Kohai-hai" made in 1819. e) Miscellaneous Resources in Area Illustration 44 (ca. 1889) shows a rather large structure west of Pu'ukohola standing in the shade of several coconut trees on the beach. It appears to be some sort of shelter or enclosure possibly part of the royal compound? A local informant mentioned that in the Pelekane area, around the coconut trees, stood a fairly large beach house that he thought had been built for King Kalakaua, constructed in a manner very different from most Hawaiian homes. (David Kalakaua became king in 1874.) A spring, "Waiakane," reportedly exists in the water about fifty feet offshore a little south of Mailekini Heiau. This may be the spot mentioned by Ellis as a favorite bathing place of the local residents. Other sites Soehren mentions in the Pelekane area include an old marine railway, several pictographs, stone fences surrounding modern house lots, a concrete-lined well that once served the Kawaihae area (possibly the spring named Waiakapea on Jackson's 1883 map), and an old charcoal oven, consisting of a low concrete dome about eight by twelve feet with a door facing the sea. A local informant said that this "kiln" (Illustrations 55 and 56), constructed with a burnt coral and lime plaster, was built by a Japanese man, lori, who cut wood in this area with the permission of the Parker Ranch. The trail that passes through Pelekane on toward Spencer Beach Park is part of the old, six-foot-wide King's Trail encircling the island.

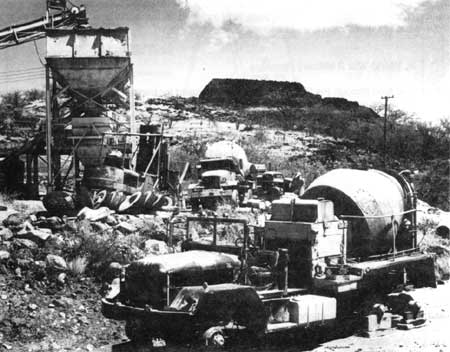

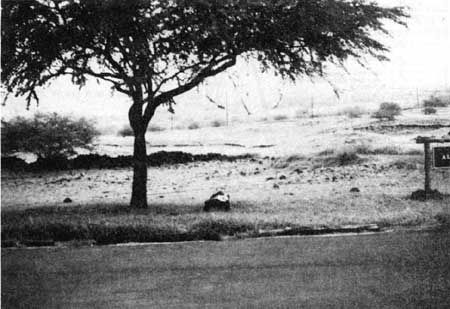

In the 1920s the Parker Ranch constructed a wagon road through the Pelekane area past Mailekini Heiau to a charcoal kiln inland of 'Ohai'ula Beach, where Spencer Beach Park is now located. This used to be a toll road for locals who found it provided easier access to the beach than the shoreline trail. The collier, the afore-mentioned lori, evidently built a second, improved road later, leading over toward the pavillion at Spencer Beach Park. Fishermen and some hog raisers also moved into the area, living by the 1930s and 1940s along the beach in raised, temporary huts thatched with grass or coconut supplemented with odd bits of lumber, with tin or iron roofs and lanais, and with small fishponds in between. People also came just for the weekend, including wealthy haole (whites), who erected boat houses and dry-docked their boats in the area of the coconut trees. The marine railway must have been built about that time for repairing these boats. This occupation resulted in a variety of junkyards, fences, pig pens, and abandoned refuse in the area, most of which has been cleaned up. In the 1960s a concrete mixing plant stood immediately inland of Pelekane. Surplus liquid concrete resulting from the cleaning and flushing of the delivery trucks each day flowed down into the Pelekane area and can still be seen today. Only a few trees mark the Pekelane area, which is surrounded by kiawe. Seeds of that plant arrived in the islands in 1828; its dense, thorny growth has obscured the platforms and stone walls delineating the former palace grounds. (Kiawe is now managed by prescribed burns to reduce growth and clear the historical scene.)

G. Stone Walls Associated with Pu'ukohola Heiau Early photographs show stone walls veering seaward from the northwest and southwest ends of Pu'ukohola Heiau. Reportedly some of these stones were used in construction of the county road running between Pu'ukohola and Mailekini heiau. Walls that appear to be delineating boundaries appear on George E. Gresley Jackson's 1883 map of Kawaihae Bay. A.B. Loebenstein's 1903 map of Kawaihae shows these walls also. Kamakau mentions that Kamehameha occasionally retreated to the "tabu district of Mailekini below Pu'ukohola." Perhaps these walls outlined that sacred district. Or, Marion Kelly surmises, they might have been built as cattle exclosures. As mentioned earlier, during his stay at Kawaihae, the Reverend William Ellis enjoyed a "refreshing bathe" in some warm springs a short distance south of the two heiau. He described the springs as rising on the beach a little below the high water mark. At low tide the water bubbled up through the sand and filled a small cistern constructed of stones piled close together on the side towards the sea, creating a small bathing place. Local informants mention a similar structure, or Queen's Bath, in the area of Spencer Beach Park. In an area called Puhapahaleumiumi, where Ka'ahumanu, Kamehameha's favorite wife, used to live, and which was restricted to the use of women, was a round stone cistern six feet in diameter in which Ka'ahumanu used to bathe. It was reportedly not the same place as the warm spring. Nearby lay the stone walls or foundations of Ka'ahumanu's house. A tidal wave has since destroyed this bathing area. Whether or not this area was included in the boundaries delineated by the stone walls of Pu'ukohola Heiau is unclear.

H. World War II Military Remains A tank road runs through the Pelekane area that was used for transporting tanks from the harbor to the Pohakuloa maneuvers area on the slopes above. There are also within the national historic site foxholes or gun emplacements from this period. Archeologist William Bonk, conducting surveys in North and South Kohala, mentioned finding a roughly circular, walled enclosure that could have been either a fisherman's shelter or a small gun emplacement, "many of which were constructed along this coast during World War II." (Recent archeology in connection with road surveys indicates some C-shaped structures were World War II "home guard" rifle pits.) I. Other Resources Soehren found a number of other cultural features in the area of Pu'ukohola Heiau. These include house platforms paved with water-worn pebbles, stone wall enclosures (goat pens?), stone fences surrounding house lots, grave sites, and house site delineations. Numerous stone walls, thought to be cattle exclosures dating from the nineteenth to twentieth centuries, are visible along the road to the visitor center. The number of cultural remains left indicates that a dense population once lived in this area.

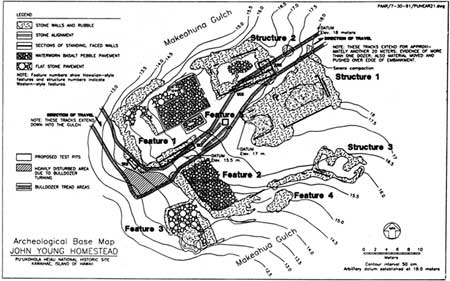

Illustration 75 is an undated photo believed to have been taken possibly as early as the 1880s. The large church on the right-hand side of the picture appears to be standing on a ridge somewhere above present Spencer Beach County Park. This may or may not be within the present park boundaries. A structure does appear in this location on Jackson's 1883 map, but it is not identified. Clara Whelden, in her description of Pu'ukohola Heiau noted earlier, stated the temple was near a church, but did not elaborate further on that structure. J. John Young Homestead 1. Lands Given to John Young by Kamehameha John Young received properties from Kamehameha in accordance with the ancient custom of a victorious chief distributing conquered lands among his loyal supporters for services rendered. After the battle of Nu'uanu on Oahu, further land distributions were made, including the ahupua'a of Kawaihae 2 (East Kawaihae) to Young. Sometime prior to 1827, a segment of Kawaihae 1 was included in Young's property in recompense for the murder of one of his men by an agent of the king. The lands given to prominent early foreigners such as Young, Davis, and Don Francisco de Paula Marin were generally acknowledged to belong to them in as full and legal a sense as the king's land belonged to him. In the early 1820s the Reverend Tyerman noted that "Mr. Young occupies so much land that his contribution [taxes to the king for use rights of the land] amounts to a hundred dogs per annum." Young's Hawai'i Island property included three estates at Waiakea in the Hilo district and one in Puna district. These properties were scattered, as were those given to other high chiefs, as Kamehameha sought to impede the possible consolidation of a rival's resources. In addition to having a residence in the area of Kamehameha's court at Kealakekua Bay for his use when conducting business there, Young established a permanent residence on his plantation at Kawaihae. At the time of his death, Young possessed twenty-nine estates on Hawai'i Island, five on Maui, one each on Lana'i and Moloka'i, and two on O'ahu. His possession and use of these lands continued to be endorsed by succeeding rulers after Kamehameha's death, with more formal legal recognition of the family's interest in these lands resulting finally from the Mahele of 1848. Although Young had died by the time of that land division, his property was awarded to his wife and children, including the children of Isaac Davis that he had adopted. According to Apple, "Young's service to Kamehameha was considered to be so great that Young's heirs did not have to pay commutation for their mahele awards."

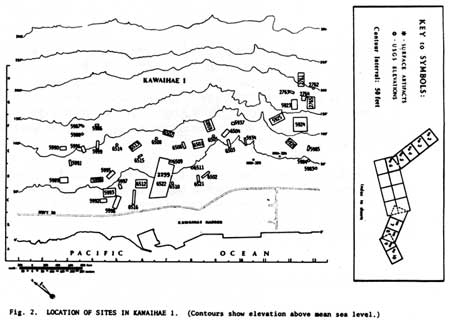

2. Kawaihae Land Divisions One of the ahupua'a Kamehameha gave his prime minister Kalanimoku, who has been mentioned previously in connection with the early history of Kawaihae, was that known as Kawaihae Komohana now referred to as Kawaihae l. This became Kalanimoku's principal residence and he its resident chief. Upon his death in 1827, the throne reclaimed his property, which became a part of the crown lands. The Young family homestead was Kawaihae Hikina (Kawaihae 2), containing Pu'ukohola Heiau. The boundary between Kawaihae Komohana and Kawaihae Hikina underwent various changes. When these lands were first awarded to Kalanimoku and John Young, both were good friends and both in the service of Kamehameha. At that time the boundary between the two properties lay along Makahuna Gulch, which carried a considerable amount of water. At some time during this period, a staff chief under Kalanimoku murdered a staff chief loyal to Young. As compensation, Kalanimoku suggested moving the boundary to add a considerable portion of his land to that of Young. Accordingly the boundary moved north to Kauhuhu Gulch, also a flowing stream most of the time. By the 1870s, however, the functional local boundary had reverted to the traditional one of Makahuna Gulch. Older residents who cared having died, and memories of the earlier agreement having faded, the boundary was formally changed back to Makahuna Gulch in 1903.