A

Cultural History of Three

Traditional Hawaiian Sites

on the

West Coast of Hawai'i Island

Overview of Hawaiian History

by Diane Lee Rhodes

(with some additions by Linda Wedel Greene)

|

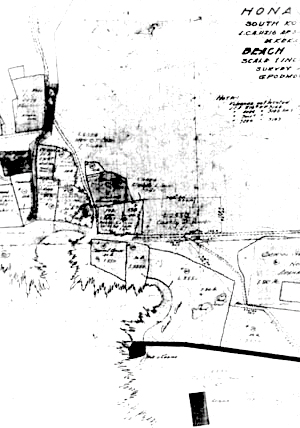

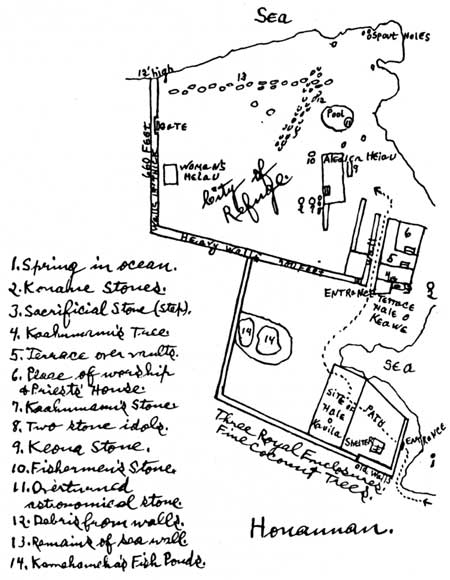

Chapter 9: Pu'uhonua o Honaunau

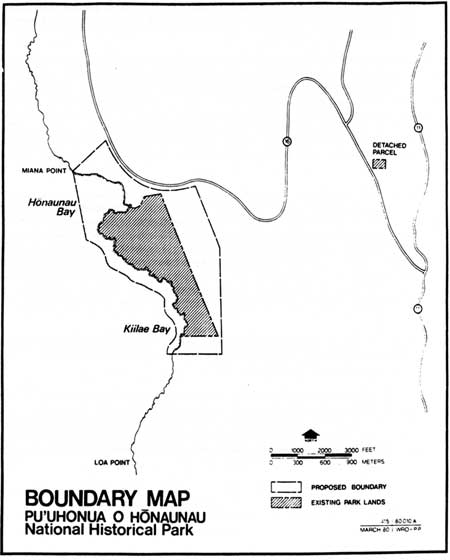

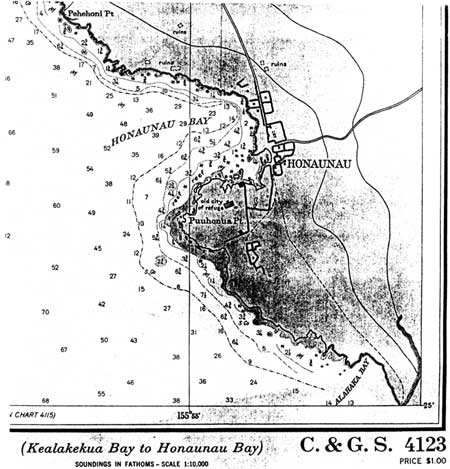

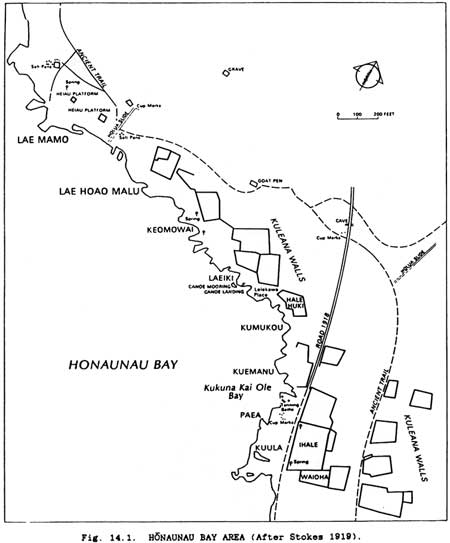

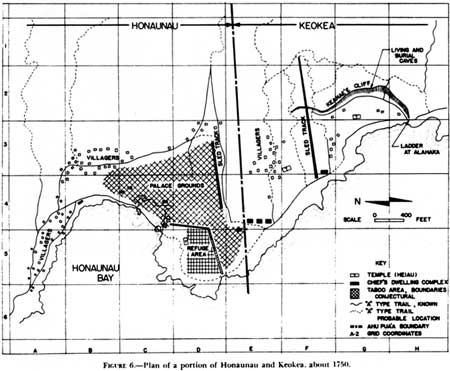

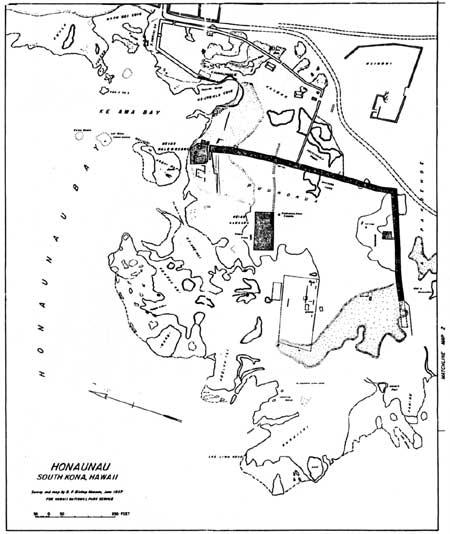

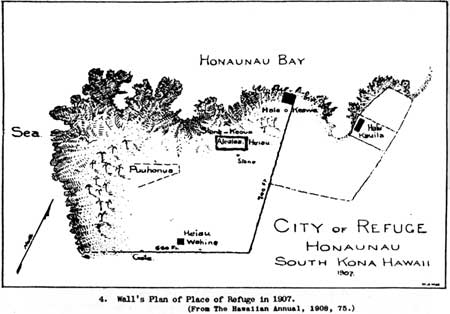

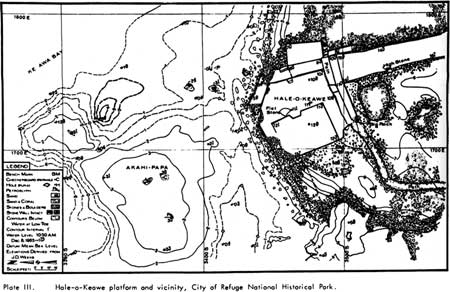

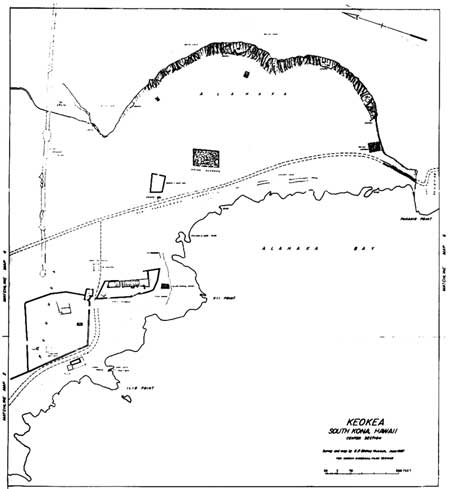

National Historical Park A. Setting Pu'uohonua o Hoaunau, "Place of Refuge of Honauhau," is located in the ahupua'a of Honauhau, in South Kona, on the west coast of the Island of Hawai'i. The present park includes the coastal portions of three ancient land divisions: Honaunau, Keokea, and Ki'ilae. It lies about midway between the larger towns of Kailua to the north and Miloli'i to the south. Located next to the ocean, the park is reached via a secondary road off the Mamalahoa Highway. It consists here of a large flat tongue of pahoehoe lava flanked by three bays, Honaunau to the north and Alahaka and Ki'ilae to the south. In the vicinity of Honaunau Bay, the park includes the refuge itself, nearby palace grounds, royal fishponds, a royal canoe landing area, stone house platforms, and temple structures. The boundaries of the refuge are formed by a wall starting at Honaunau Bay and extending in a southwesterly direction for more than 600 feet, at which point a leg turns to the west and runs again southwesterly about 400 feet toward the sea.

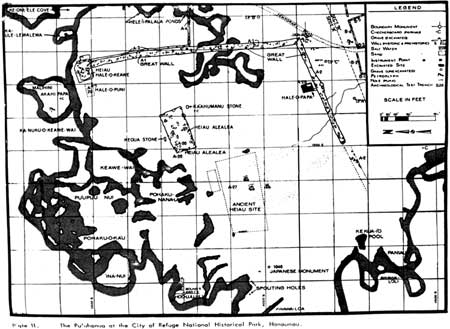

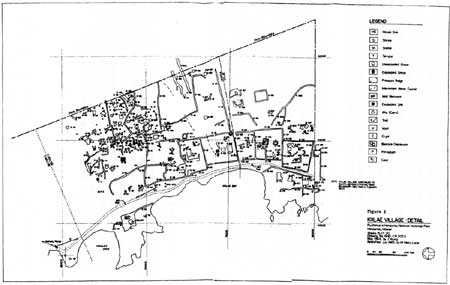

Here, as elsewhere along the Kona Coast, lava flows (these from Mauna Loa) are the dominating coastline feature. The refuge is situated on a tongue or small peninsula of black pahoehoe lava jutting into the ocean and forming the southwest wall of Honaunau (Ke Awa) Bay. Within the curve of the bay nestles the small village of Honaunau, once the home of chiefly retainers and commoners, now supporting only a small number of houses. From here one can see what is perhaps the most spectacular natural feature of the park — the Keanae'e pali (cliff), a fault scarp paralleling the shore about one-tenth of a mile inland. The imposing appearance of the cliff, which is arc shaped, more than 100 feet high, and 1,000 feet long, is due to the metallic-hued ancient lava flows frozen in time as they cascaded over the cliff edge toward the sea, creating "festoon lava." The early inhabitants used the numerous cave openings and lava tubes in the cliff face as residences, burial chambers, and possibly for refuge from the elements. From the ocean inland to the beach the area that used to be barren, dry, open, and dotted with scattered large lava boulders (deposited by tidal action or brought in for construction purposes) is now overgrown with koahaole and opiuma. The area historically supported stands of pill grass used for thatching houses, pandanus, kou, kamani, and noni, with cocoanut palms providing some shade around the refuge itself. About a mile inland, the scene changes to dense foliage as a result of the more abundant rainfall and the presence of decomposed lava. The early Hawaiians appreciated this area's fertility and their descendants continue to utilize it for growing large quantities of coffee, macadamia nuts, plumeria, avocados, papayas, and other tropical fruits. North about four miles on the Kona Coast is Kealakekua Bay, the scene of the second significant contact between native Hawaiians and Europeans. It was there, at the site of the early Hawaiian villages of Napo'opo'o and Ka'awaloa, that Captain Cook's ships, the Resolution and Discovery, dropped anchor after discovering Kaua'i in 1778. There Cook was worshipped as the physical manifestation of the god Lono in the temple of Hikiau. And there he eventually lost his life during a sudden battle with the natives at the water's edge near Ka'awaloa. A monument on the north side of the bay marks his death site. Hikiau Heiau, restored in 1917, stands on the east side of the bay. The area between Kealakekua and Honaunau bays is renowned as the Moku'ohai battleground, site of the 1782 conflict between the forces of Kamehameha and those of Kiwala'o for dominance over the island after the death of Kalani'opu'u, king of Hawai'i at the time of European contact. Kamehameha's troops succeeded in killing Kiwala'o and routing his warriors, although the latter's half-brother Keoua escaped to carry on the battle until his own death at the hands of Kamehameha's followers at Pu'ukohola Heiau. Immediately south of the refuge, in Keokea, a satellite village of scattered residential sites, including that of King Keawe, hugged the coast in ancient times. Inland remains of this settlement consist of two heiau, a holua, and the burial cliffs mentioned earlier. A little farther south, within the present southern boundary of the park, is a portion of Ki'ilae Village, occupied from prehistoric times until 1926. There residences arose around a well, called Wai-ku'i-o-Kekela, named for Kekela, a resident of the area, daughter of John Young and mother of Queen Emma. Nearby are lava tube refuge caves useful in time of war. Today the refuge and associated residential and temple sites, walls, trails, and village remains are in ruins. Non-native shrubs and trees, vines, and a dense undergrowth of grass form a thick cover over the pahoehoe lava flow, which is periodically exterminated in an attempt to restore the landscape of the eighteenth century and expose significant archaeological features. Park facilities include a visitor center, parking lot, headquarters building, and a picnic area.

B. Description of Refuge Area Early in the area's prehistory, a ruling chief declared the tongue of black lava flow extending out into the ocean southwest of the bay a sanctuary protected by the gods. There kapu breakers, defeated warriors, and criminals could find safety when their lives were threatened if they could reach the enclosure before their pursuers caught them. A massive stone wall around the sanctuary marked the boundary, while a heiau within the walls afforded spiritual protection. Later a temple was built at the north end of the wall to hold the sacred bones of the ruling dynasty, who would act as perennial guardians of the pu'uhonua. The refuge site today consists of an area partially surrounded by a thousand-foot-long wall of pahoehoe lava about seventeen feet thick and ten feet high. The north side of the structure is open to the bay and the west side to the sea. Within or next to the enclosure were several significant structures, including the Hale-o-Keawe, the 'Ale'ale'a Heiau, the "Old Heiau," and the Hale-o-Papa (Women's Heiau). Other notable features include a konane stone (papamu), a fisherman's shrine, and two large stones, one reportedly serving as a hiding place for Queen Ka'ahumanu during a quarrel with her husband King Kamehameha and the other used by Chief Keoua. A small enclosure east of Hale-o-Keawe contains two fishponds used by Hawaiian royalty. The Hale-o-Keawe housed the bones of the paramount chiefs descended from 'Umi and Liloa, some placed in wicker caskets woven in anthropomorphic shapes. This sepulchre of the very high ali'i lent Honaunau its great sanctity. The entire area surrounding the complex was densely settled in aboriginal times and is now replete with significant archeological remains. It is clear that a well-organized society once flourished in this area. Archeological features here illustrate all aspects of ancient society relating to the religious, economic, social, and political life of early Hawaiians. This way of life began disappearing with Cook's arrival in 1778 and underwent more deterioration when Liholiho abolished the kapu system in 1819.

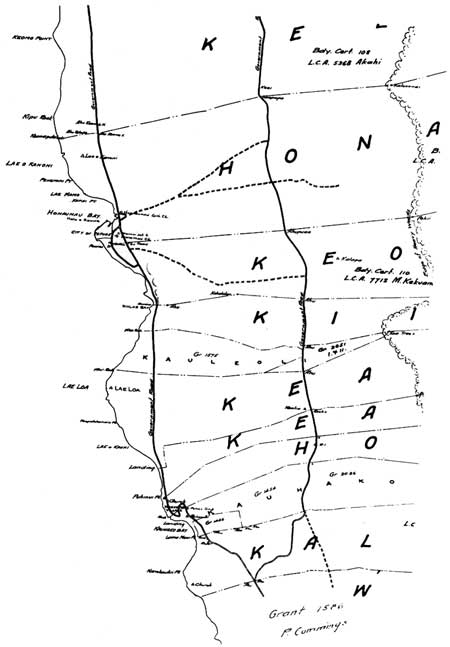

C. Development of Honaunau Ahupua'a As described earlier in this study, the sheltered, temperate Kona Coast of Hawai'i became an ideal settlement area for the early Polynesian peoples who migrated to the Hawaiian Islands. The calm waters of Honaunau Bay provided abundant fish and other marine resources, while its gentle upland slopes offered conditions conducive to the growth of abundant crops of taro, bananas, sweet potatoes, sugarcane, and later, breadfruit. Also available were stands of hardwood trees for constructing residences and religious structures and for manufacturing canoes. Much of Honaunau Bay's attraction lay in its sheltered sandy beaches where canoes could easily land. A number of brackish springs, actually tide pools in which fresh water from rain and natural seepage accumulated on the surface of the salt water, provided a dependable water supply. It is not surprising the cove quickly became a favorite residence of Hawaiian royalty. The refuge was an important part of Honaunau, the traditional seat of the chiefdom of Kona. The ruling chief and his court occupied the area at the head of Honaunau Bay and along the shore to the south. Lesser chiefs and commoners serving the court and priests resided on the north shore of the bay, toward the mountains, and possibly at Keokea and Ki'ilae villages to the south. All residences were basically one-room, wooden framework, thatched-roof structures. The chief's complex would have consisted of several houses. The ancient village of Honaunau was the ancestral home of the Kamehameha dynasty, serving in ancient times as a major Hawaiian religious and cultural center. In 1823 William Ellis noted that "Honaunau . . . was formerly a place of considerable importance, having been the frequent residence of the kings of Hawaii, for several successive generations." When King Keawe-i kekahi-ali'i-o-ka-moku of Kona, Kamehameha's great-grandfather, died about 1650, his bones were placed in a temple constructed on a platform next to the refuge. His mana, inherited from his ancestral gods, and that of his descendants became the power protecting the refuge at Honaunau. The structure in which his remains reposed, the Hale-o-Keawe, became a royal mausoleum, holding the bones of several more of Kamehameha's ancestors and thereby endowing the area with extreme sacredness and the refuge with powerful guardian spirits. Although the canoe traffic of ancient times moved easily in and out of the small harbor of Honaunau Bay, the water was not deep enough to accommodate the European and American trading ships that began arriving in Hawai'i late in the eighteenth century. For that reason Kamehameha and other ali'i anxious to initiate social and economic interaction with foreigners moved to other harbors, such as Kailua and Honolulu. This was the beginning of the decline in Honaunau's importance, which increased with the abolition of the kapu system in 1819, at which time the benefits of absolution and forgiveness provided by places of refuge became unnecessary. Honaunau over the years declined in population as it changed in character from a royal residence of kings, a religious and political center, and a refuge site to just another seacoast village that gradually lost inhabitants to the upland sections in the 1840s as happened in other places. In the Great Mahele, the ahupua'a of Honaunau went to Miriam Kekau'onohi, a granddaughter of Kamehameha. She took as her second husband Levi Ha'alelea, a descendant of the Kona chiefs, who inherited Honaunau when she died. After his death, the administrator of his estate sold the land at auction in 1866 to W. C. Jones, agent for Charles Kana'ina, the father of King Lunalilo. Because Jones never paid for the land, Charles R. Bishop bought it in 1867 as a present for his wife, Bernice Pauahi. Six years after her death, Bishop deeded Honaunau to the Trustees of the Bishop Estate who leased the portion occupied by the refuge to S.M. Damon. In 1921 the county of Hawai'i leased the pu'uhonua and the adjoining picnic area from the Bishop Estate for use as a county park. In 1959 the federal government obtained 165 acres, including the ancient refuge, from the Trustees for the establishment of a national park. Part of the land was from the ahupua'a of Honaunau and part from Keokea. Kamehameha Ill had granted the ahupua'a of Keokea to Kekuanaoa in 1848; his daughter, Ruth Ke'elikolani, acquired it upon his death in 1868. At her death in 1883, the land went to her cousin Bernice P. Bishop. D. Places of Refuge 1. Types In ancient Hawai'i, during times of war, old men, women, and children from surrounding districts fled to places of safety, either in the mountains, in caves, or to pu'uhonua to await the outcome of the conflict in safety and to escape reprisal if their warriors met defeat. William Ellis noted that

Pu'uhonua translates literally as pu'u (hill), honua (earth). Possibly the word pertained originally to a fortress on a hill, which is also implied by Ellis's quotation above and one from Samuel Kamakau presented a little later in this section. The term is also applied to cave refuges, which were actually large lava tubes into which small groups of people fled from a pursuing enemy. Sometimes stone walls across the entrances allowed only one person at a time to enter, in a stooped position, providing defensive advantage for those inside. Places of refuge were a necessary adaptation because of the particular culture of the early Hawaiians, regimented as it was by the kapu system of prescribed behavior, and preoccupied as its leaders became in achieving power and authority — pursuits that frequently dictated conflict and wars. 2. Origins According to the historian Marion Kelly, the Hawaiian concept of asylum and its various elements evolved as a natural outgrowth of institutions and cultural patterns that already formed an established part of Polynesian society. These arrived in Hawai'i as part of the general pool of cultural knowledge and were elaborated upon and refined to conform with evolving Hawaiian beliefs related to the supreme sacredness and inherited power of ruling chiefs. As Kelly states,

Anthropologist Kenneth Emory's views supported this statement. He determined that the sanctity of a place of refuge related directly not only to the inherited sacred power of the chief who established it but also to his ability to maintain political control of the district. 3. Historical Associations with Hebraic Cities of Refuge Early European visitors to Honaunau, trying to place the Hawaiian term pu'uhonua within a context they could understand, used the term "city of refuge" for this area. Although it little resembled the cities of refuge in Jerusalem, because it was neither a city or even a settlement and because protection was granted to both the innocent and the guilty, the name clung to the site through succeeding generations of visitors and scholars. A "logical" conclusion of this misnomer was that the Hawaiian people must have descended from one of the lost Hebrew tribes. Abraham Fornander dedicated a paragraph in his first volume on the Polynesian race to "Cities of Refuge," sacred areas that he noted had often been discussed as "another instance of Hebraic influence upon the customs and culture of the Hawaiians." Even King Kalakaua, in describing the two Pu'uhonua, or places of refuge, on Hawai'i Island, went so far as to venture that their existence suggested "a Polynesian contact with the descendants of Abraham far back in the past, if not a kinship with one of the scattered tribes of Israel." 4. Use Within Hawaiian Culture Access to the pu'uhonua o Honaunau would have been gained by land from the south or by swimming into it from the north. The presence of the palace complex just east of the refuge prohibited entry from that side; the kapu system ordered immediate death for a commoner who set foot or cast a shadow on a royal residential area. The pu'uhonua was a place that was always open, and anyone who reached it was assured of protection no matter their class or type of infraction. A large, enclosed refuge such as the one at Honaunau was considered extremely safe not only because of the physical barrier of the surrounding wall but also because the presence of a heiau within or near the walls assured the protecting influence of guardian deities. Fleeing to one of these places was the only escape from death for a criminal, vanquished warrior, or kapu violator. These designated sacred sites offered the chance to be purified by a kahuna pule for one's sins and to resume life in the community free of the fear of punishment. Kelly, in describing the interrelationship in a pu'uhonua between spiritual mana and personal safety, suggested that

De Freycinet described Hawaiian pu'uhonua enclosures in 1819 in some detail:

Constance Cumming had been told that, having crossed the threshold of the refuge and attained sanctuary, "The first act of the fugitive was to give thanks in presence of the image of Keave, and he was then allowed to rest in one of the houses built specially for refugees, within the sanctuary. . . . This concept of providing places of safety was recognized throughout the Hawaiian Islands, resulting in a functioning pu'uhonua in each district throughout ancient times. Designated pu'uhonua changed over time with changing policies. The refuge at Honaunau was the largest walled one in Hawai'i and is thought to have been the most continuously used. Today it is also the best preserved. Established by the Kona chiefs in prehistoric times, it functioned into the historic period. 5. Use During Reign of Kamehameha After consolidating his power, Kamehameha abolished most of the old pu'uhonua, distributing them to his war leaders, and established new ones. Only Kaua'i, never the scene of Kamehameha's conflicts, retained all its original refuges. Kamakau states that prior to Kamehameha's rise to power there had been pu'uhonua on Hawai'i Island in Kohala, Hamakua, Hilo, Puna, and Ka'u. But when the Kona chiefs gained ascendancy, only the pu'uhonua at Honaunau was kept, either because the Kona chiefs were supreme or because the land was so dry it was of little other use. Samuel Kamakau also discussed the fact that not only places but people were considered pu'uhonua:

Designation as a pu'uhonua was applied to high chiefs because of their position as rulers, a position supported by the mana or sacred power they had inherited from their ancestors and that gave them the right to spare lives or extend mercy. As ruling chief, Kamehameha

E. Pu'uhonua o Honaunau 1. Early Descriptions by Europeans Early accounts of the pu'uhonua o Honaunau consist primarily of descriptions of the Hale-o Keawe and/or brief mention of the dimensions and configuration of the Great Wall. In the historic period a number of early European visitors and missionaries saw, were impressed by, and even tried to depict on paper, the thatched mausoleum of Hale-o-Keawe and its associated refuge. Because this temple was left to deteriorate after other religious structures had been destroyed, it afforded a final view of the relics, and a parting reflection on the kapu, that had comprised such an essential part of the ancient Hawaiian religion. These early accounts provide our only historical picture of the remains of the pu'uhonua at Honaunau. a) Cook Expedition, 1779 The first known visit by Europeans to the pu'uhonua at Honaunau was by some of Captain Cook's officers in March 1779. Lieutenant James King recorded that

b) Archibald Menzies, 1793 The second recorded sojourn in the area was a brief one, on February 28, 1793, by Archibald Menzies, botanist of the Vancouver expedition, who arrived in the village of Honaunau at the tail end of an exploratory expedition into the uplands behind Kealekekua Bay. He and his companions

After a soothing massage, and after contracting with the inhabitants to provide water for their ships, Menzies and his companions spent an uneventful night in the village. Little interested in ethnography, Menzies seemed unimpressed by the presence of the refuge or its meaning in Hawaiian culture. He mentions only that during the night, "in a large marae close to us we now and then heard the hollow sounding drums of the priests who were up in the dead hour of the night performing their religious rites." c) John Papa I'i, 1817 John Papa I'i, a participant in, and observer of, Hawaiian public affairs as a companion of Liholiho, stated that Kamehameha's son regularly visited the Hale-o-Keawe during his journeys to various luakini as his father's representative in those rituals necessary to replenish their mana. Liholiho would begin this series of prescribed visits in Kailua, proceed up the coast to Kawaihae, and then continue on around the island, finally stopping at Hale-o-Keawe. The following is the only eye-witness account of an official state visit to the Hale-o-Keawe, made in 1817, and of the accompanying rituals:

d) Reverend William Ellis, 1823 The first detailed description of this "city of refuge" by a foreigner was penned by the Reverend William Ellis while visiting the area on his tour of the island with representatives of the Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Very interested in learning all he could about Hawaiian society and religious beliefs, and already acquainted with many aspects of the culture and able to speak the language, he immediately realized the significance of the pu'uhonua. He was less impressed by the village of Honaunau, which then contained about 147 houses. Despite the large number of dwellings, the only accommodations he and his companions could find consisted of a mat spread on the ground in an open canoe shed. There they passed their nights, beset by ''swarms of vermin" and "the unwelcome intrusion of hogs and dogs of every description." Because Ellis was feeling the effects of indigestion, thought to have been caused by drinking the brackish water along the coast, he and his party tarried in the area for another couple of days while he recuperated. During that time his companions examined the surrounding countryside. Inland two to four miles they found a prosperous population living comfortably in comparison to those on the coast. Breadfruit trees, cocoanuts, and prickly pear thrived in large groves. By this time, the pu'uhonua at Honaunau had been abandoned for four years. Ellis and his companions were quite impressed by the Hale-o-Keawe, although they were unable to understand why it had not been destroyed during the general destruction attending the abolition of the kapu system. Ellis's description of the structure is lengthy but irreplaceable in providing some idea of its original appearance:

Ellis and his companions found the refuge, signifying clemency and empathy with the plight of the common people, a refreshing change to the deserted "heathen" temples and abandoned altars that conjured up vastly different pictures, those of "human immolations and shocking cruelties." Many of the later visitors to the area based their descriptions on this account by Ellis, adding few other relevant details or observations.

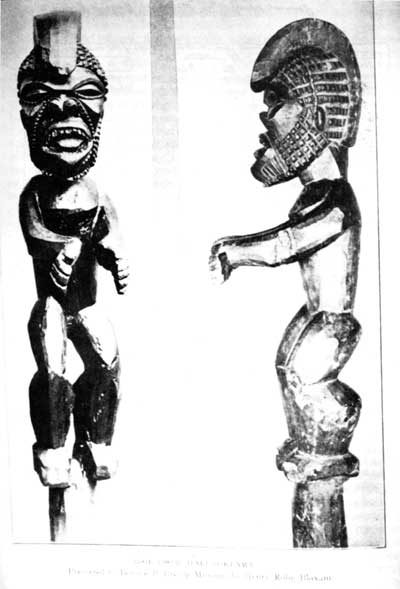

e) Andrew Bloxam, 1825 Two years later, in 1825, the British frigate Blonde, commanded by Captain (Lord) Byron, came to Hawai'i to return the bodies of Kamehameha II and his queen, Kamamalu, who had succumbed to measles during a royal visit to England the previous year. On board ship were Naturalist Andrew Bloxam and Botanist James Macrae. During their sojourn in the islands, these men visited a number of ports and sites of interest. In addition, Byron was more than willing to serve as an ally to the Hawaiian high chiefs in their efforts to promote Christianity by removing all sacred objects from the Hale-o-Keawe. Liholiho's death had resulted in Kauikeaouli's ascendancy as Kamehameha Ill. Because the new ruler was underage, Kalanimoku served as regent and co ruler with Ka'ahumanu. Both were new converts to Christianity, Kalanimoku specifically giving Byron permission to remove articles from the temple. On the morning of July 15, 1825, Bloxam reported that

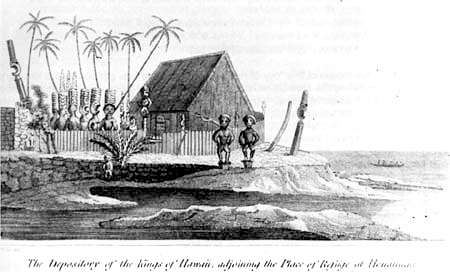

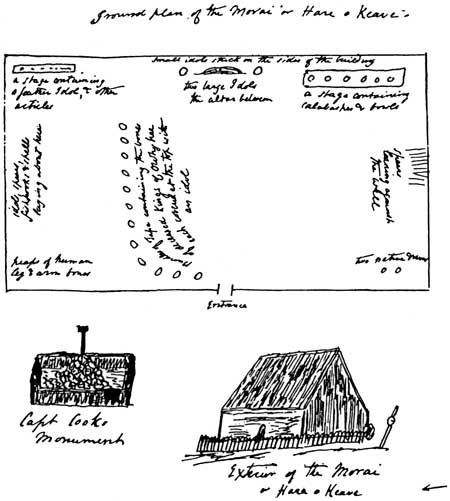

This account does not mention the images within the enclosure that Ellis noted nor those on the fence. Byron's account, presented later, however, does mention images within the courtyard. Bloxam added to the significance of his visit by making sketches of the exterior of the Hale-o Keawe and of its interior arrangement.

f) Reverend Rowland Bloxam, 1825 The Reverend Rowland Bloxam, Andrew's uncle, added a few details on the Hale-o-Keawe's interior furnishings:

g) Lord G. A. Byron, 1825 Lord Byron's account of this trip provides additional information of interest and importance:

The two high chiefs accompanying Byron, Kuakini (governor of the island of Hawai'i) and Na'ihe (chief of South Kona and guardian of the Hale-o-Keawe), were somewhat disturbed by this looting of the temple, but remained silent. They did, however, prevent removal of the bones.

h) James Macrae, 1825 Botanist James Macrae, not a member of the first tourist party off the Blonde, visited the pu'uhonua the next day:

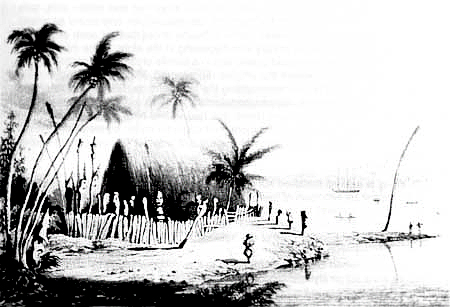

The Blonde's artist, Robert Dampier, contributed to this documentation by sketching the Hale-o Keawe, producing a rather stylized rendering of the structure against a background more closely resembling Kealakekua Bay to the north. An engraving made from that drawing accompanied the formal report of the voyage and is a valuable source of information on the appearance of the structure. It should be noted that because the crew of the Blonde removed many of the Hale-o Keawe images, they have been preserved in a number of private collections and museums both in the United States and Europe and provide an important record of early Hawaiian religious art that might otherwise have been lost. i) Laura Judd, 1828 The next foreign visitor who left an account of the pu'uhonua was Laura Fish Judd. She came to Hawai'i Island in 1828 in company with her missionary/physician husband, Gerrit P. Judd, who was part of a committee exploring a site for a health station on the nearby mountain slopes. The failing health of many of the pioneer missionaries had become a source of concern, and it was believed that a station in the bracing mountain atmosphere might be good for them (Waimea in North Kohala was later selected). During Mrs. Judd's residence at Ka'awaloa she visited the temple at Honaunau accompanied by Na'ihe and Kapi'olani:

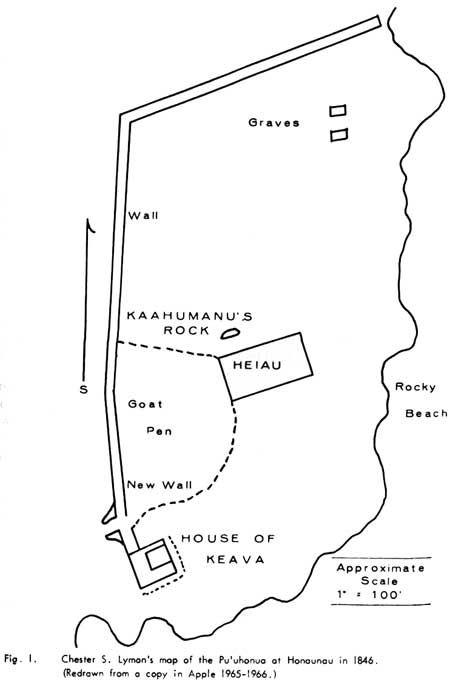

j) Later References to the Site Chester Lyman, a Yale University scientist visiting Hawai'i, sketched the pu'uhonua in 1846, his map showing that the area between the Great Wall, the Hale-o-Keawe, and the northeast end of 'Ale'ale'a Heiau was fenced off as a goat pen. Lyman writes that on December 2, 1846,

English author Samuel Hill visited Honaunau in the late 1840s and found a village containing about forty huts with not more than 100 residents. He described the pu'uhonua enclosure as having walls only three to four feet high and being full of coconut trees. The village and refuge ruins also rated only slight mention from George Bowser who, while compiling a directory of the Hawaiian kingdom in the early 1880s, noted at Honaunau only

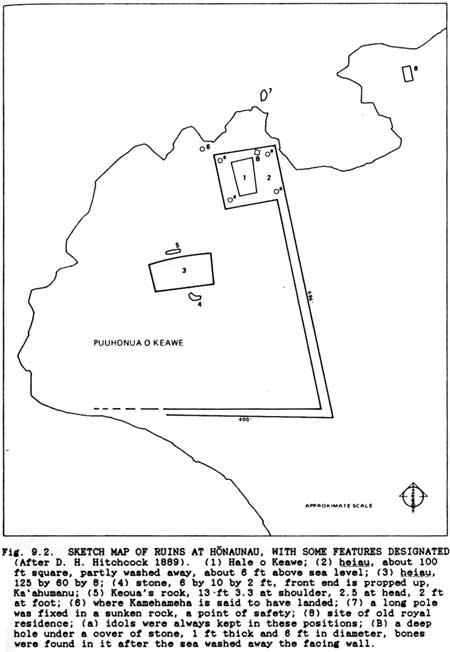

D. Harvey Hitchcock, a Hilo artist, sketched the refuge area in 1889 and depicted many of the major structures and features.

2. Early History a) Original Chronology of Pu'uhonua Development Information on the erection of structures at Pu'uhonua o Honaunau has come primarily from ancient Hawaiian oral traditions, early European travel accounts, oral history from residents who once lived in the area, and archeological fieldwork from the early 1900s to the present time. Samuel Kamakau made the following statement concerning the setting aside of the refuge and construction of the Hale-o-Keawe:

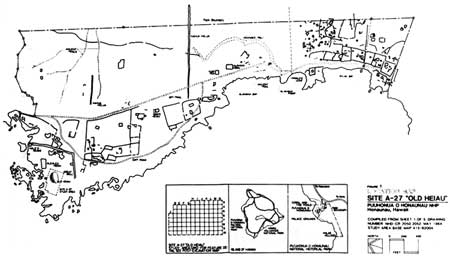

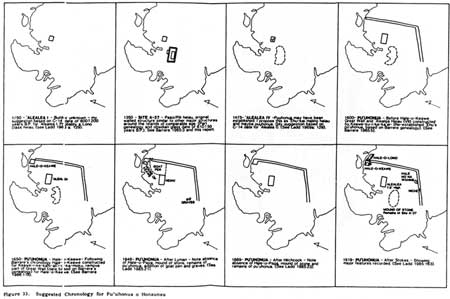

Abraham Fornander stated that Kanuha, son of Keawe-i-kekahi-ali'i-o-ka-moku built the Hale-o-Keawe. A chronology of the establishment of the pu'uhonua and construction of the various heiau and other features within it has been subject to change and revision over the years. Anthropologist Dorothy Barrère first attempted in 1957 to determine the prehistoric use of the pu'uhonua at Honaunau, a project hampered by the lack of much traditional knowledge. Several sketchy oral traditions, her own genealogical studies, and archeological data accumulated to that time convinced her that the refuge had undergone three main phases of construction. These began with the erection of the open platform temple now referred to as the "Old Heiau," which she thought probably provided the initial protective mana for the refuge. Next came 'Ale'ale'a Heiau and finally Hale-o-Keawe. Barrère surmised that the Great Wall had been built during either the first or second phase of construction. Barrère found it extremely difficult to determine when the original pu'uhonua had been set aside, although her genealogical work deduced that the first chief who would have held uncontested control over his kingdom and thus would have been in a position to establish and maintain the sanctity of the refuge was 'Ehu-kai-malino, the ruling chief of Kona and a contemporary of Liloa, the supreme chief of the island. Both men were active about 1475 A.D. If 'Ehu had established a pu'uhonua at this time it probably would have been primarily intended for kapu breakers, because there was no inter-chiefdom rivalry in progress that would have necessitated a war refuge. Barrère theorized that the first heiau took form at this time in association with the pu'uhonua. Open to conjecture was the question of what happened to the refuge under 'Umi, Liloa's son, who inherited his supreme power. As new ruler, he could either have abolished the pu'uhonua completely or have reaffirmed its sanctity. The next mention Barrère found of the pu'uhonua at Honaunau surfaced four generations after 'Umi, after the line of inheritance of the Kona chiefs had been firmly established through 'Umi's descendants. One tradition states that it was Keawe-ku-i ke-ka'ai, a son of Keakealani-kane, ruler of Kona, Kohala, and Ka'u three generations after 'Umi, who built the pu'uhonua and Hale-o-Keawe. Other traditions state the latter was built for Keawe-i kekahi-ali'i-o-ka-moku, living two generations after the other Keawe. Archaeological evidence at that time indicated that the eastern segment of the Great Wall originally ran north to the water's edge and that a portion of it had been removed for construction of the Hale-o-Keawe. On the basis of what was known at that time, Barrère believed it was possible to accept both traditional explanations — that Keawe-ku-i-ke-ka'ai had reconstructed the old pu'uhonua by building the 'Ale'ale'a Heiau platform, and maybe the Great Wall, and that the Hale-o-Keawe was built for Keawe-i-kekahi-ali'i-o-ka-moku, Kamehameha's great-grandfather, in a later period, ca. A.D. 1650.

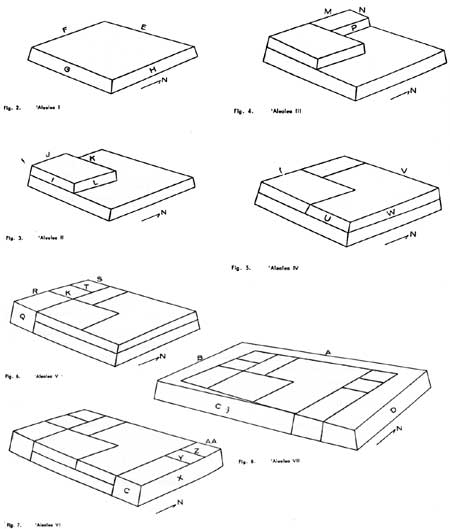

b) New Archeological Data Forces Revisions to Chronology After Barrère had developed this chronology, important new information came to light through the excavation of 'Ale'ale'a Heiau in 1963. That work showed that this structure had passed through seven developmental stages, described as 'Ale'ale'a I-VII. On the basis of those findings, NPS Archeologist Edmund Ladd, of the Pacific Area Office, revised the construction chronology in several respects. He theorized that sometime prior to A.D. 1475, the "Old Heiau" and stages I to III of the 'Ale'ale'a Heiau were built, the pu'uohuna possibly being in existence at that time. (Heiau could exist independently of a sanctuary, but a sanctuary would not be viable without an associated heiau to add spiritual protection.) About A.D. 1475, Ladd believed, 'Ehu-kai-malino added stage IV onto 'Ale'ale'a III. At that time he could have reaffirmed an existing pu'uhonua or might have established the original one. About A.D. 1500 'Umi possibly reaffirmed the earlier pu'uhonua by adding stages V and VI to 'Ale'ale'a. Ladd theorized that about A.D. 1600, Keawe-ku-i-ke-ka'ai reaffirmed the pu'uhonua by building stage VII of 'Ale'ale'a around stage VI. Ladd then suggested that in A.D. 1650, 'Ale'ale'a VII was abandoned when the Hale-o-Keawe was built for Keawe-i-kekahi-ali'i-o-ka-moku. On the basis of the new archeological evidence, Barrère also took another look and revised her chronology, tossing out some basic assumptions she had made earlier and suggesting that the "Old Heiau" had been constructed by Pili-ka'aiea, the new ruler Pa'ao installed in the islands, in the thirteenth century; 'Ehu-kai-malino had then constructed 'Ale'ale'a I at the same time he established the pu'uhonua, about A.D. 1425; 'Umi then enlarged 'Ale'ale'a in stages II, Ill, and IV and possibly constructed the Great Wall, ca. A.D. 1500 (based on Apple); Keawe-ku-i-ke-ka'ai further enlarged 'Ale'ale'a in stage V ca. A.D. 1625 (Apple); and then Keawe-i-kekahi-ali'i-o-ka moku enlarged 'Ale'ale'a in stage VI in ca. A.D. 1675 (Apple). Barrère added a new twist by suggesting that Kamehameha enlarged 'Ale'ale'a in stage VII sometime between 1793 and 1803 and then constructed Hale-o-Keawe between 1813 and 1819. Supporting her theory on the refuge's longevity, Barrère cited a traditional legend from very ancient times describing what rites a priest followed after a refugee entered the pu'uhonua o Honaunau. The legend validates later stories of the area's being an ancient place of refuge, of the inviolability of its kapu, and of the presence of guards to enforce its sanctity and of kahuna who performed religious rites and ceremonies. It is known that during the Battle of Moku'ohai in 1782, men, women, and children of the camps of both sides took refuge in this pu'uhonua. In addition, Reverend Ellis noted an account of the area serving as a refuge for warriors retreating from that battle after the death of Kiwala'o. Further data from the archeological work on the "Old Heiau conducted during 1979 to 1980 appeared to show that stage I of 'Ale'ale'a predated the "Old Heiau" and might even be 200 years older than originally thought. In a final effort to clarify the sequence of events, Ladd conjectured that 'Ale'ale'a I had been built ca. A.D. 1250 by an unknown person; 'Ale'ale'a II and III were added ca. A.D. 1250-1475 by another unknown builder; the "Old Heiau was then constructed ca. A.D. 1350, influenced by the teachings of Pa'ao and Pili; 'Ehu-kai-malino added 'Ale'ale'a IV ca. A.D. 1475 and also established the pu'uhonua; 'Umi added 'Ale'ale'a V and VI ca. A.D. 1500 and also possibly reaffirmed 'Ehu's pu'uhonua; Keawe-ku-i-ke-ka'ai added 'Ale'ale'a VII ca. A.D. 1600, when the Great Wall was constructed; and finally Keawe-i-kekahi-ali'i-o-ka-moku built the Hale-o Keawe by removing a portion of the Great Wall ca. A.D. 1650. 3. Later History of the Pu'uhonua and of Hale-o-Keawe The pu'uhonua, as indicated, was not needed as a sanctuary after the abolition of the ancient Hawaiian kapu system. The Hale-o-Keawe was spared destruction at that time possibly because of its special status and its extreme sacredness due to its connection with the Kamehameha dynasty and its function as the repository for the ancestral bones of the reigning family. Russell Apple has theorized that possibly Liholiho himself, in agreement with Ka'ahumanu, decided to retain the repository of his famous ancestors' bones as a "royal mausoleum of the Kamehameha dynasty." Despite the acculturation taking place in Hawai'i at that time, many continued to adhere to the old traditions. Although worship at the old temples and of the old gods was almost impossible with their destruction after 1819, the fact that Hale-o-Keawe still existed provided opportunities for relic worship and placement of offerings to ancestors. Ka'ahumanu and others who had converted to Christianity considered this a pagan and objectionable practice and probably an embarrassment. Therefore, threats to the structure's existence arose with the visit of the regent Ka'ahumanu to the Hale-o-Keawe in 1829. Ka'ahumanu was a strong convert to Christianity and steadfastly resolved to completely sever Hawaiian ties to the old religion by getting rid of this last vestige of "paganism." Missionary Hiram Bingham recounted that

The removal of the bones took place in late December 1828 or early January 1829, and at least partial destruction of the house occurred soon thereafter. The deified bones were removed from Hale-o-Keawe and placed in two large coffins, or wooden boxes, which were secretly interred in Hoaiku cave in the Ka'awaloa cliffs at Kealakekua Bay, where they remained for almost thirty years. Sometime afterwards (ca. 1836?) the Hale-o-Keawe's surrounding fence was dismantled and its sacred timbers and perhaps part of the palisade were used in construction of a government building in Honolulu. According to Professor W.D. Alexander, in January 1858 Kamehameha IV toured the windward islands in the British sloop Vixen commanded by Captain Meacham. Arriving at Ka'awaloa, he ordered the keeper of the royal burial cave to unseal it during the night and allow the coffins from Honaunau to be loaded on board ship. Transported to Honolulu, they were entrusted to the protection of Governor Kekuanaoa, who was also official guardian of royal tombs. In 1865, after completion of the royal mausoleum in Nu'uanu, the coffins were carried there during the night in a torchlight procession and laid to rest.

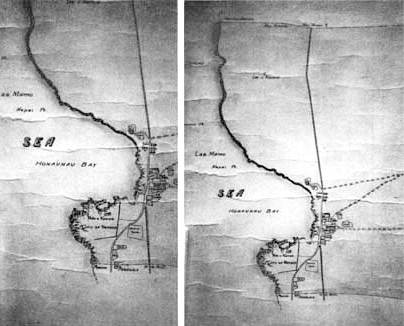

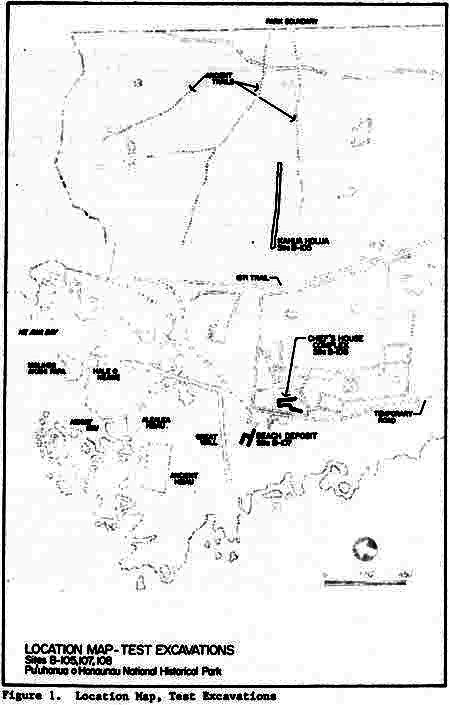

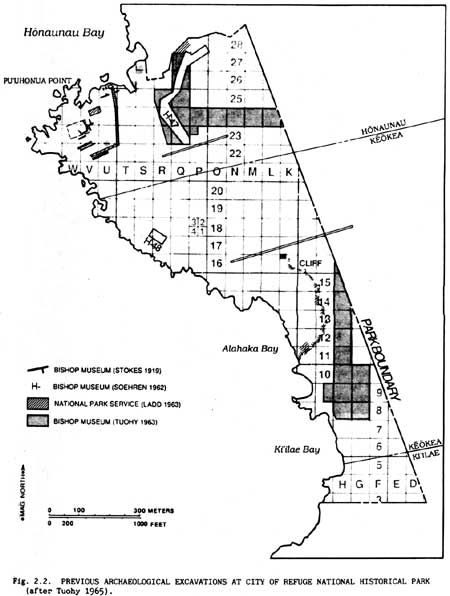

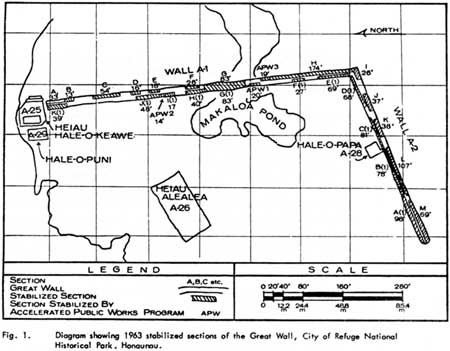

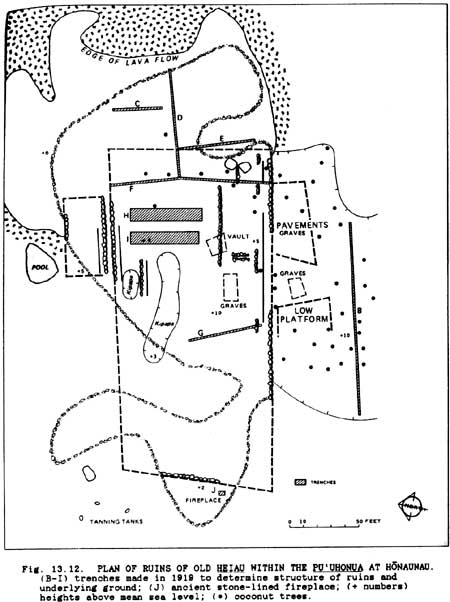

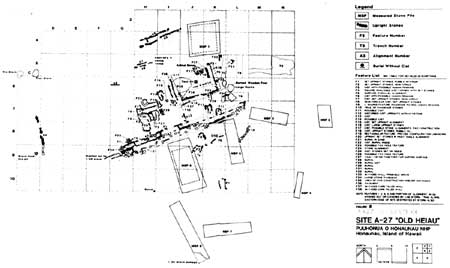

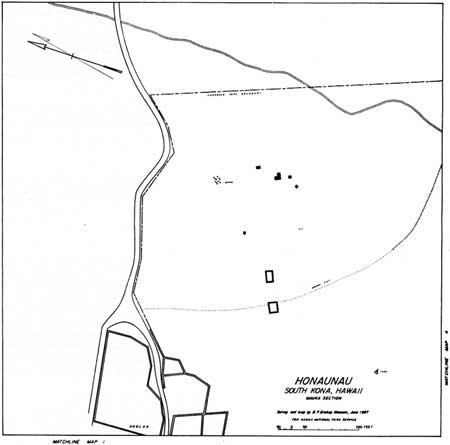

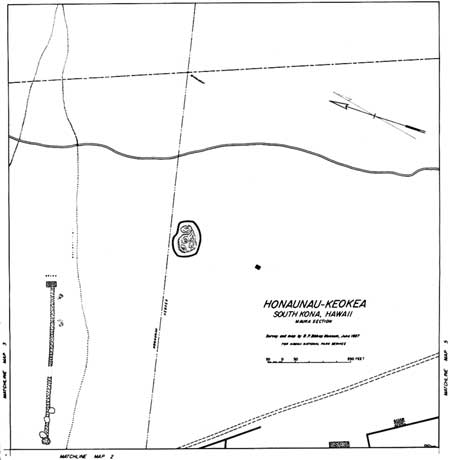

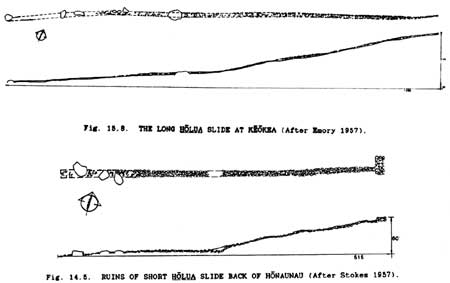

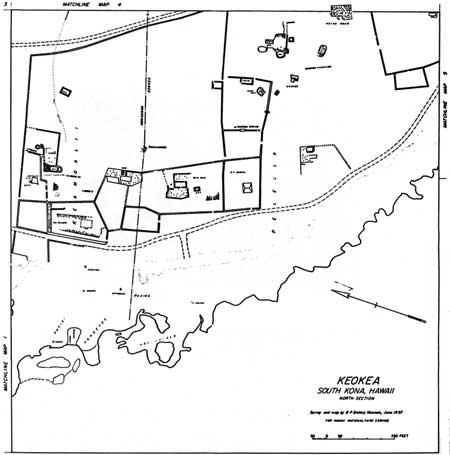

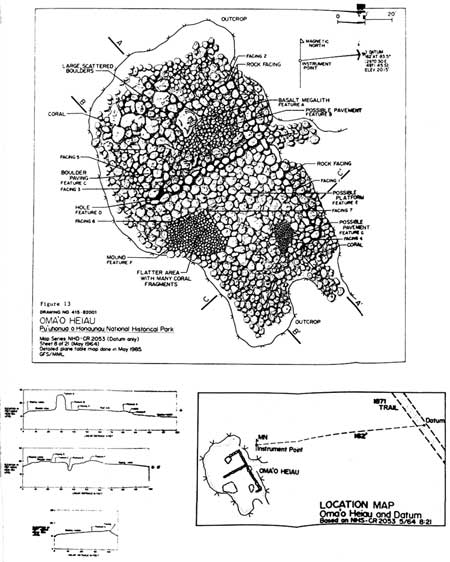

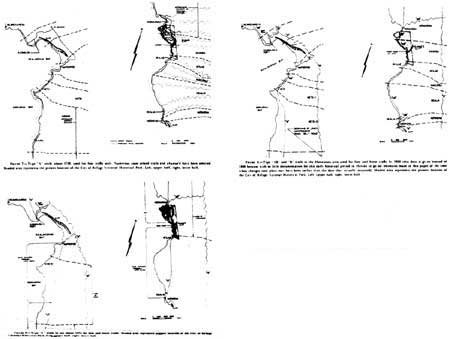

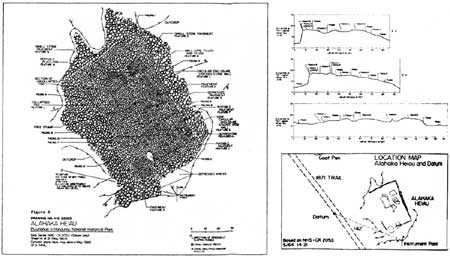

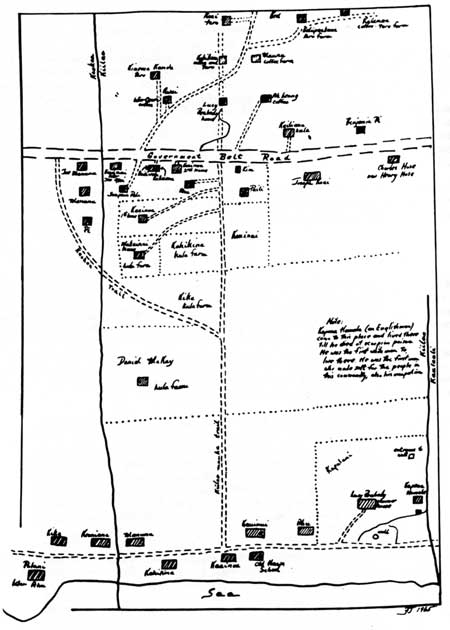

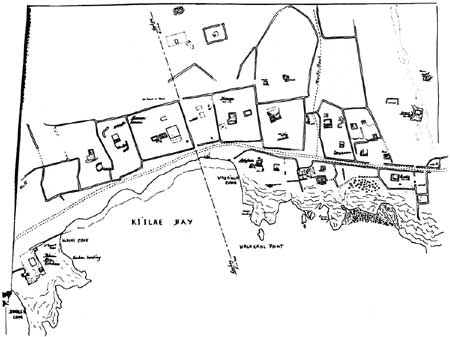

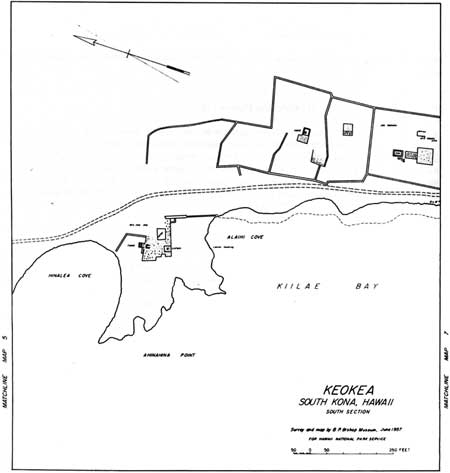

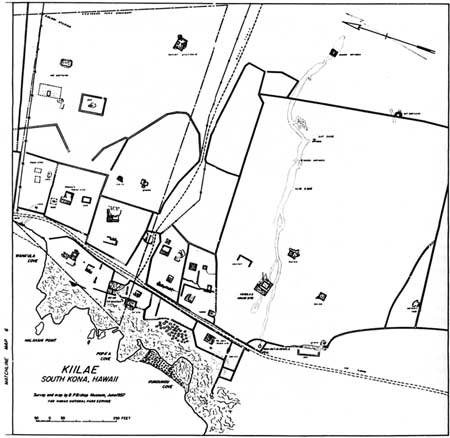

Missionary Levi Chamberlain had been present at the removal of the bones from Hale-o-Keawe and listed the names of the chiefs whose bones went to Ka'awaloa. Barrère, after studying the list and genealogies, discovered that possibly as many as sixteen of the chiefs were direct descendants of one chiefly mating. She concluded, therefore, that Hale-o-Keawe was primarily the depository of bones of one family descended from Keawe-nui-a-'Umi, whose son was the first hereditary ruler of Kona. The earliest interments in the house were probably designated for deification as ancestral gods for the next generations. Not all descendants of the family were placed there, notable exclusions being that of women, because this was a heiau, and of priests, a class that could not be be deified. Several questions concerning the Hale-o-Keawe remain unresolved. After being emptied of relics, and after souvenir pieces of kauila wood had been given to the missionaries, what happened to the structure? It appears to have remained standing, possibly by intention on the part of Ka'ahumanu, who either believed that the removal of relics had so decreased its power among the people that it no longer posed a threat to Christian beliefs or who left it to Na'ihe to destroy. Na'ihe continued as guardian of the bones secreted in the cave in the Kealakekua cliffs until his death in 1831, and he might have managed to procrastinate on the house's destruction until Ka'ahumanu's death that same year. Missionaries Ephraim W. Clark and Levi Chamberlain saw the Hale-o-Keawe still standing in February 1829 as they passed in a canoe by Honaunau Bay, and the Reverend John D. Paris noted it again in 1841. Yale astronomer and surveyor Chester Lyman, visiting in Hawai'i, noted in 1846 the walls "yet quite entire," the stone foundation of the Hale, and remains of the wooden palisade. Henry Cheever stated about 1850 that only a fence of posts remained on site, and Samuel Hill about the same time spoke of a few stakes remaining as well as the temple refuse pit. A series of earthquakes beginning in 1868 and resulting tidal waves (tsunami) probably aided the obliteration of the temple platform and any associated structures. Damage through neglect and natural forces, plus sinking of the land over time, had basically cleared the site of the temple by 1902 and dramatically changed the coastline. Questions concerning Hale-o-Keawe still await definitive resolution. We can only make educated guesses about who built it and when and where the bones of its original inhabitants now finally rest. The presence of associated structures, such as quarters for temple priests and for caretakers of the royal tomb or shelters for the refugees, has not been conclusively determined through either documentary research or archeological fieldwork to date. 4. Early Study, Restoration, and Archeological Efforts The first effort to preserve features of the pu'uhonua began after the Bishop Estate acquired the property in the late 1880s. S. M. Damon leased the property from the estate and financed restoration work on the primary structures, severely damaged by tidal waves or high surf, in 1902. Surveyor Walter A. Wall supervised these attempts to repair and restore the 'Ale'ale'a and Akahipapa heiau and parts of the Great Wall. Other than drawing a plan of the refuge, Wall did not professionally document the nature or extent of his work. Comparison of photos of the Great Wall before and after 1902 show little difference in its appearance, indicating only minor repairs at that time. In 1919 Horace Albright, then Field Assistant to the Director of the NPS, visited the pu'uhonua and instantly recognized its archeological, historical, and cultural values. He suggested it should be a national monument, preserved just as were cliff dwellings and other cultural sites because of its interest and educational benefits. Also in 1919 John F.G. Stokes, then curator of Polynesian Ethnology at the Bishop Museum, undertook the first formal archeological fieldwork at the site by investigating the ruins and attempting further repair and restoration of the pu'uhonua and the Hale-o-Keawe. He mapped the complex and carried out excavations and restoration of several structures, concentrating on the Hale-o-Keawe, the Great Wall, and the sandy beach within the pu'uhonua, and also digging some exploratory trenches in the mound of the "Old Heiau. He found human burials common in the beach sand inside the refuge and lust outside the southern arm of the Great Wall. In the course of that work, Stokes conducted many on-site interviews with local Hawaiians, finding that even by that time, reliable information on the area prior to the overthrow of the kapu system was scant. He restored the Hale-o-Keawe stone platform and repaired walls. The county of Hawai'i finally leased the site as a park to preserve the area pending further action affording the site national recognition. In 1949 several officials of the NPS, including Regional Historian V. Aubrey Neasham, completed a comprehensive historical survey and analysis of the City of Refuge, also recommending its recognition as a national monument or a national historic site to preserve and interpret it for future generations. In 1952 Henry P. Kekahuna and Theodore Kelsey began a project to locate, examine, and record the historic sites in Honaunau, Keokea, and Ki'ilae from the seashore to 2,500 feet upland. This involved recording all features of legendary and historical interest, sketching archeological remains, and preparing an account of their findings. In the course of that project they studied materials in the Bishop Museum, interviewed elderly residents of the Honaunau area, compiled a descriptive map of the pu'uhonua, and wrote a series of articles in the Hilo Tribune Herald describing features in the refuge and its vicinity. In 1956 Kekahuna compiled an interpretive map of the Ki'ilae ruins. This effort succeeded in furthering the movement for establishment of a national park. In 1956 Stokes came out of retirement to help the Bishop Museum Department of Anthropology produce a major two-volume report, The Natural and Cultural History of Honaunau, Kona, Hawaii, which it prepared for the NPS and which contains the heretofore unpublished work of Stokes as well as ethnohistoric studies by Dorothy Barrère and Marion Kelly. Dr. Kenneth P. Emory supervised the surveying, inventorying, and mapping of resources and the collecting of traditional and historical data on the City of Refuge and its surrounding area. His contributions are also included in the report. This document, the basic data source for the park, was reproduced in one volume in 1986. After establishment of the national park, the NPS began a long-range restoration program, including additional research. It initially contracted with the Bishop Museum in 1962 and 1963 to conduct further archeological excavations at the new park. This work was intended to build upon that accomplished by Bryan and Emory in 1957 on the area's natural and cultural history. Although Robert N. Bowen briefly surveyed caves in the Keanae'e Cliff in 1957, Lloyd J. Soehren of the Bishop Museum began the first modern excavations at Honaunau in 1962 by conducting test excavations in two areas where the NPS planned construction of public facilities. The sites Soehren tested included an arc-shaped area around the base of pahoehoe flows inland from the 1871 trail, between the "Holua Honaunau and the north boundary of the park. Features there were threatened by planned construction of public and administrative facilities in the area inland of the pu'uhonua. The other area he surveyed was part of the coral sand dune extending from the southern end of the Great Wall nearly to the foot of Keanae'e Cliff at Alahaka. The portion tested was in Keokea at Pele'ula. Park Archeologist Edmund Ladd followed this work with extensive tests between the park entrance road and some of Soehren's sites early in 1963 and also conducted other investigations that year in connection with stabilization efforts at the horse ramp in Keokea, at the Great Wall, and at 'Ale'ale'a Heiau. Donald Tuohy also carried out excavations in 1963, along a proposed road right-of-way within the park boundaries leading from the park entrance toward Ki'ilae Village. This work included areas adjacent to the proposed roadway and others threatened with destruction both from natural causes and increased public use. Since 1961 the NPS has overseen stabilization and restoration of the Great Wall and the 1868 Alahaka ramp, restoration of the 'Ale'ale'a Heiau stone platform, restoration of the Hale-o-Keawe platform and reconstruction of its temple images. A base map locating the Alahaka-Keanae'e ruins came out in 1963. Alahaka and Oma'o heiau have been cleared of vegetation, mapped in detail, and stabilized. Historian Frances Jackson completed a historical study of Ki'ilae Village in 1966, and archeological base maps completed in 1968 show the major walls and stone structures there. Test excavations were conducted at Site B-105 (holua sled track), B-107 (beach deposit), and B-108 ("Chief's House Complex") in 1968. In 1980 the "Old Heiau" was excavated.

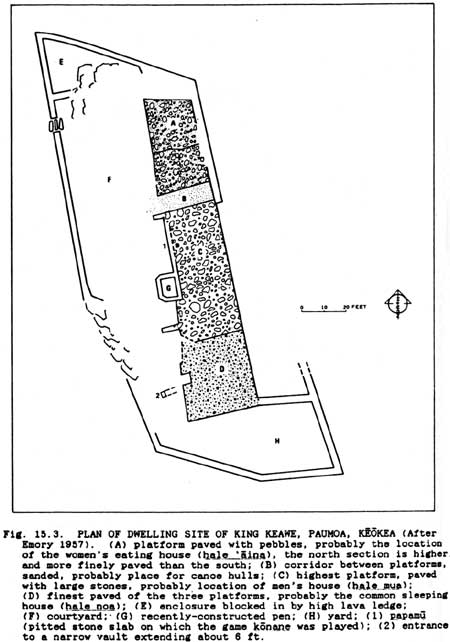

F. Description of Resources: Pu'uhonua Area 1. Palace Grounds The royal palace grounds are located in the vicinity of Keone'ele Cove, inland from the pu'uhonua. Once filled with numerous grass huts, the area still contains evidence of chiefly occupation, including He-lei-palala pond, fed by underground springs, which held fish for royal consumption, and a papamu stone for playing konane, a game similar to checkers. This constituted a sacred area in ancient times and commoners could not walk across it or even cast their shadows upon it without risking death. Keone'ele Cove was the spot for landing royal canoes and was kapu to commoners. The royal residential area was separated from the refuge by the eastern segment of the Great Wall. Another tongue of lava, called Ka-ule-lewalewa, adjacent to Keone'ele Cove on the west, shows a line of four vertical holes along its eastern border. These were probably for a row of images that acted as guardian sentinels for the mausoleum. (The palace grounds and other features noted within the pu'uhonua may be seen on Map 1.) A local informant in 1919 provided information that the royal precincts comprised Lots 18-20 and part of 22 (see Podmore 1918-19 map). The house platform on Lot 19 at the edge of the bay was the site of part of King Keawe's "palace" (Kauwalamalie), probably the reception hall, with living quarters nearby. Two other house platforms were found at that time, in Lots 18 and 20. The former held a grass house in 1888 and on the latter in 1919 stood an old wooden house inhabited by the caretaker of the grounds. The informant stated that this house of Keawe's was the site of the 'awa party at which Kamehameha broke relations with Kiwala'o. (Kamehameha had arrived in Honaunau to mourn and pay respects to his dead uncle Kaiani'opu'u and to perform the 'awa ceremony for his cousin Kiwala'o to purify him from contamination caused by association with the corpse.) Lots 20 and 22 contain the royal fishponds. Between 1860 and 1870 (probably ca. 1867), Lot 18 was the site of a cocoanut "planting bee" and luau held by Bernice P. Bishop, as chiefess of the land. (Stokes believed this was not just an ordinary planting of a coconut grove, but involved the ceremonial taking possession of the land by the new owner.) At that time the lot was the village gathering place. The enclosing walls on Lots 18-20 were modern (within the previous seventy years). However, this informant did mention an ancient boundary line there that was regarded as very sacred; any commoner whose shadow fell on it was killed. Stokes found many holes in the solid pahoehoe that might have supported kapu sticks. (As late as 1919 people in the Honaunau area could remember being told that while the kapu system was in effect, the common people had to detour around the royal precinct, passing along the shore in the morning and around back of the village in the afternoon hours to insure that their shadows did not fall upon that sacred ground.) According to this same 1919 informant, a building on Lot 19 in this area served as a school ca. 1830. The structure had a framework of ohia logs bound together with coconut rope and was covered with ti leaves. The National Park Service removed several early stone walls from the royal compound area in 1963.

2. Pahu tabu (Sacred Enclosure), Great Wall a) Early Descriptions The Reverend William Ellis described the refuge enclosure as being "of considerable extent" in the form of an irregular parallelogram. Walls enclosed one side and both ends, with the other side open to the beach. A low fence ran across the northwest end. Ellis's party measured the wall and found it to be 715 feet long and 404 feet wide, with walls 12 feet high and 15 feet thick. Ellis saw holes in the top of the wall that had supported large images spaced about four rods apart along the entire extent. A 1966 study by Apple and Macdonald of the shoreline area just north of the Great Wall confirmed that a dryland access route to the refuge had existed. It is now submerged during periods of high tide. Their study showed the water there had risen about one foot per century. Samuel Kamakau describes the Great Wall as follows:

Thrum further elaborates upon the writings of Kamakau, stating that:

b) Construction Details The local informant quoted earlier gave Stokes the following information in 1919 in regard to the pu'uhonua and the process of forgiveness:

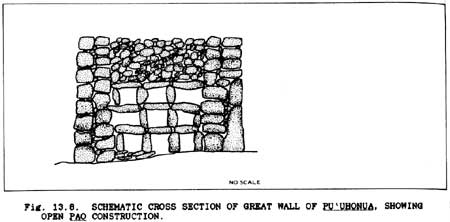

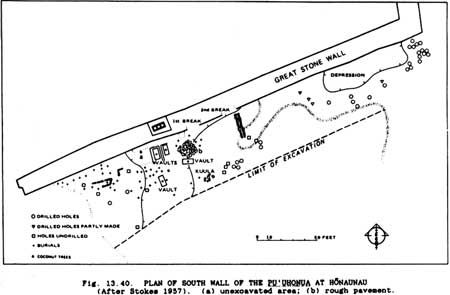

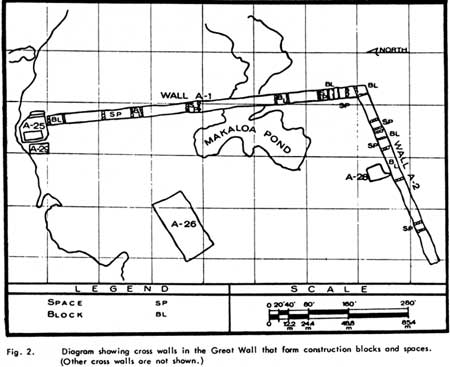

Measurements taken during archeological work by Archeologist Edmund Ladd showed the wall to be 17 feet thick, 12 feet high, and almost 1,000 feet long — an L-shaped structure enclosing an area of about five acres. The north wall that existed in Ellis's time is gone. Part of the north end was rebuilt to accommodate construction of the Hale-o-Keawe. The wall forms two sides of the enclosure, which is open to the sea on the other sides. As with all Hawaiian masonry structures, notably the heiau described earlier in this report, the pu'uhonua enclosure is composed of two outward facing walls with a central core of rubble fill. The wall material comprises uncut, mortarless, basalt blocks that fit together with the smoothest surfaces of the stones facing outward. The stones used on the outside veneer wall were probably specially selected for their smooth surfaces and were probably collected nearby. Small stones were used for the infilling, or chinking, between the large rocks, and the rubble core between the two outside walls is comprised of broken, more irregular, stones. In the wall at the north end are some very large boulders, many of them weighing more than 1,000 pounds. They must have been moved to the site with great difficulty, possibly with the use of wooden pry bars, rollers, and skids. The foundation of the wall rests on solid pahoehoe primarily, although several sections are built over sandy areas or sinks. The wall's structural weakness results not only from a weak foundation in several places, but also from its mortarless construction. c) Restoration Efforts A great deal of restoration work has been accomplished on the Great Wall. By 1902, more than eighty years after abandonment of the pu'uhonua, the wall lay in ruins. Archeological evidence indicates that several hundred feet of the west end of the wall were destroyed by tidal waves. As mentioned, S.M. Damon, a trustee of the Bishop Estate, commenced repairing this structure and the 'Ale'ale'a Heiau and 'Akahipapa ("women's Heiau Hale o Papa) at his own expense. W.A. Wall supervised the reconstruction of the wall, basing his work on known facts and oral traditions of local informants. No official records of this project were kept, although Stokes attempted to gain some knowledge of the level of work accomplished by talking with Wall years later and with some of his workmen in 1919. In addition, Wall drew a plan of the refuge and related sites that was reproduced in The Hawaiian Annual for 1908. d) John F.G. Stokes's Observations In 1919 Stokes and a Bishop Museum crew began excavation work and limited restoration of the stone platform of Hale-o-Keawe and repair of the Great Wall. A diagram by the Reverend A S. Baker in 1921 shows the details of structures at that time. Stokes made several observations in the course of his work on the Great Wall. He believed, for instance, that the south wall had probably originally extended out onto the flat west as far as the sea, with an opening somewhere along it. More than 100 feet of the west end of the south wall that had been destroyed by tidal waves had been restored in 1902, but the wall was moved slightly north of the original line during restoration. By comparing photographs taken in 1889 and 1919 of the middle part of the outer face of the east wall, it was apparent that the 1902 reconstruction had taken a foot or two in height off the original wall. Stokes also determined that the north-running wall continued through the platform of the Hale-o-Keawe, suggesting that at one time it extended clear to the water's edge. The platform of the Hale-o-Keawe merely incorporated the base of that wall in its construction. (Dr. Emory inserted a comment into Stokes's written notes on the Great Wall that a break in the east wall close to the north end for an entrance had been installed prior to 1846 and may have been one of the original entrances that Ellis mentioned.) Stokes measured the largest stone in the outer (east) facing of the north-running wall and found it measured 6-1/2 feet high, a little more than 5 feet wide, and 2 feet thick. For most of its course, the east wall rested on bare lava; those sections that had collapsed by 1902 were on soft ground.

Where the interior of the wall had been exposed either by collapse or removal of stones, Stokes found a remarkable feature. This was pao, a hollow construction technique that saved labor and materials and was invisible behind the solid facades. This caverned, honeycomb construction was accomplished by laying several tiers of lava slabs or columns across the space between the outer and inner retaining walls. This technique has only been found at Honaunau, where it was also used in the platform of Alahaka Heiau to the south. It takes advantage of the properties of the local lava rock, which is fragmented, and probably comprised a later development of the construction technique used in the stone chambers or vaults of house and burial platforms in which a row of slabs a foot or two apart are bridged over with other slabs. Although Ellis stated that he had seen holes along the top of the wall for images, none have been noted by excavators. According to native tradition, stones for the Great Wall came from Paumoa and Alahaka in Keokea ahupua'a to the south. Most of it could certainly have come from nearby sources in the vicinity of the refuge where the lava surface is broken and from which pieces appear to have been appropriated. There are few loose stones in the vicinity, indicating they were used for building purposes. Although we do not know precisely when the Great Wall was built, in terms of how it was built, Stokes noted that

e) Later Stabilization Efforts In the earlier stabilization work on the Great Wall, Wall's men had tried to utilize the same construction techniques used originally. Because dry-laid core fill construction does not withstand heavy use or remain stable without periodic upkeep, new methods were tried in 1963 to preserve the original appearance, make the area safe for visitor use, and insure minimum future maintenance. During this project, nearly eighty percent of the wall was rebuilt. Although slightly modified, the finished wall closely resembled the original. The single outside face of the wall gained additional support through construction of an inward facing wall. Carefully selected long header stones laid in the wall with their ends towards the face of the wall reinforced the outside and inside faces. The 1963 stabilization work located three burials in the Great Wall, those of an adult and two children. Because many bones were missing, it was thought the burials had been washed out by high seas, with some of the bones then being retrieved from the beach area and reburied in the walls after the 1919 restoration work. These are considered intrusive burials. Archeologist Lloyd Soehren, in noting the extreme thickness of the wall, suggested that this might have constituted an effort to protect refugees within the enclosure from the "radioactivity-like mana of high chiefs whose living quarters were located just inland from the sanctuary." Marion Kelly suggests also that, despite the protection afforded by the sanctity of the area, "the presence of this heavy wall could be interpreted as evidence that a certain degree of physical protection was necessary as insurance against intruders." 3. Hale-o-Keawe a) Early Descriptions John Papa I'i, who frequently saw the Hale-o-Keawe while it was still functioning, provided the firsthand description of the structure and associated ceremonials presented earlier. Ellis's account, the most detailed historical description of this carefully built house, thatched with ti leaves, surrounded by a fence, and protected by guardian deities in the enclosed courtyard and vicinity, remains the primary source of information on the early appearance of this structure. Additional descriptions by Bloxam and Macrae of the Blonde, along with sketches made by members of that party, provide important information on the appearance of the building and its surrounding courtyard. The furnishings of the Hale-o-Keawe removed by crew members of the Blonde included such relics as carved wooden images, spears, calabashes, and other items of lesser importance to the Hawaiians than the bones of their ancestors. Although a very important temple because of its association with Kamehameha and his ancestors, the Hale-o-Keawe was fairly small (fifty feet square) compared to other temple complexes. Because so little information is available, many questions remain about the Hale-o-Keawe. These include the number of times it was rethatched, how often the frame was replaced, and what additions or alterations were made over the years. Apple believes the temple described by early visitors such as Ellis was one that Kamehameha renovated about 1812. This was the temple the NPS later reconstructed in 1967 and 1968 and represents, he thinks, the most elaborate state of the mausoleum. In addition, it might differ from its 1812 appearance if some of the sacred images from other destroyed temples had been added to it after 1819. Apple supports this conjecture by pointing out that the well-carved image with a baby in its arms that Lord Byron saw in 1825 was not mentioned by Ellis in 1823 even though it was a most unusual form. b) Function As mentioned earlier in this report, the bones of ancient royalty were always carefully guarded and usually concealed secretly in caves. Exceptions to this practice involved the establishment of royal mausolea — special buildings for the care of royal remains that were guarded by keepers. Some additional protection was ensured by their association with places of refuge. Coverings for the remains consisted of fiber caskets, possibly with shell identification tags attached. Early descriptions of these burial places indicate that not all bones were prepared in the same manner, some being put in woven fiber baskets, others wrapped in kapa. The process of interment in these places consisted of encasing the bones of defied chiefs in woven, sennit caskets that were moulded over the skull. These were given pearl-shell eyes and the entire object was placed in bundles in the Hale. The Hale-o-Keawe symbolizes one method of Hawaiian burial practices, the one reserved for high ali'i corpses being deified. Bones of lesser chiefs were kept there also but received little preparation and were stacked in a corner of the temple. The Hale-o-Keawe definitely served as a heiau, the bones it contained being objects of veneration and its having in addition a hereditary guardian and all the other accoutrements found at a state temple, including images, offerings, altars, a refuse pit, and a palisade. If it had been merely a resting place for family bones, there would be remains of women present. The supernatural protection provided by deifying the chiefs whose bones it contained ensured the sanctity and inviolability of the refuge for all time. The erection of the Hale-o-Keawe, also called Ka-'iki-'Ale'ale'a ("the little 'Ale'ale'a"), probably resulted in discontinuance of the use of 'Ale'ale'a as the pu'uhonua heiau. After that time, according to modern-day informants, 'Ale'ale'a became a structure that the chiefs used for recreation rather than as a sacred ceremonial place. The last deification of a chief at Hale-o-Keawe is said to have been that of a son of Kamehameha, named Kaoleioku, and occurred in 1818. c) Traditional Stories Surrounding the Hale-o-Keawe Kamehameha is linked to the Hale-o-Keawe in several ways, both as its builder, as Barrère suggests, and as a suppliant to this source of great mana for the Kamehameha dynasty. Some traditional stories describe secret nightly visits by Kamehameha to the Hale-o-Keawe. One mentions his landing in the bay and entering the room containing the sacred bones of Keawe. The guardian of the temple saw him, and, by exclaiming at his presence, precipitated Kamehameha's hasty retreat. A similar tale tells of Kamehameha, possibly sometime in the 1 770s before he had gained power, disturbing the temple guard, who was stretched sleeping across the doorway, during a possible attempt to steal Keawe's bones, possession of which would mean possession of Keawe's mana or strength. d) Human Sacrifices Another question concerning the Hale-o-Keawe is whether human sacrifices were a part of deification ceremonies there. Indications are that both voluntary and involuntary sacrifices took place. Professor W. D. Alexander stated

This implies that the priests supervising the construction of the Hale-o-Keawe determined there should be no doubts about the sanctity of these premises. It has been stated that as many as eighty-four human sacrifices went into this building, the idea being that the more sacrifices made, the greater the structure's importance and sacredness, the greater the feeling of kapu, and the more protection extended to the refuge. Barrère points out that this number of sacrifices seems highly implausible because the dedication rites of a luakini the most exacting ritual, required only a few. Barrère believes that traditions suggest that sacrifices were made here prior to Kamehameha's rule, that they were offered but not required. The first sacrifice in prehistoric times that traditional sources mention was that of Keawe 'Ai, a relative of King Keawe-i-kekahi-ali'i-o-ka-moku who offered to die at the time of construction to provide added mana. Laura Judd relates an account she heard of a sacrifice probably in the late 1780s or early 1790s of a small boy, a favorite servant of Kapi'olani, as retribution for her breaking kapu by eating a variety of banana forbidden to women. A priest supposedly strangled the child on the altar of the Hale-o-Keawe. Upon the death of Kalani'opu'u, ruling chief of Hawai'i Island, in 1782, sacrifices might have been made while his body lay in state at Honaunau prior to deposition in the Hale-o-Keawe. In addition, anyone pursuing a refugee into the pu'uhonua was killed, whether by priests and their adherents, the king's executioner, or the king's soldiers is unclear. It would make sense that any bodies acquired in this way would be sacrificed to Keawe and his ancestors and descendants as retribution for violation of their protection. Apple has concluded from his studies that the bones of these human sacrifices were among those kept at the Hale-o-Keawe, that the offering of human sacrifices to the deified chiefs was a way of propitiating them in addition to prescribed prayers and other rituals. Another historical account states that one of the events leading to the battle of Moku'ohai involved Kiwala'o, heir to the government after Kalani'opu'u's death, sacrificing some of Kamehameha's followers on an altar at Honaunau, perhaps as his late father's companions in death. Kamakau states that Kamehameha authorized Hale-o-Keawe and the pu'uhonua as a place for human sacrifices, probably early in his career, immediately after winning the battle of Moku'ohai. The Reverend Henry Cheever, visiting the area in 1849, stated

One of the indications of human sacrifices and other offerings are the refuse pits associated with luakini. Samuel Hill made the first historical reference to such a feature here, noting "a cavern imperfectly covered by an enormous block of lava, but in which, we were informed, still remained the bones of several of the ancient kings of the island." Hitchcock, who sketched a plan of the refuge in 1889, identified that cover and commented on the deep hole beneath the stone that was one foot thick, six feet in diameter, and contained bones. This stone appears on the topographic map made by Wingate in 1966. During the 1902 restoration, a large flat stone lying at the water's edge was thought to be the cover of the bone pit and to have formerly sat level with the pavement of the main platform near its eastern edge. During the 1902 work, an arched cavity was found containing human bones. Other human bones were found in the northern side of the platform in 1902, and others were taken from the northwest corner of the platform about 1960. Local informants stated that this refuse pit was used to rot bones, after which they were cleaned and hung in bundles from the roof of the Hale-o-Keawe. One informant stated these were the bones of sacrificial victims, not of chiefs. Apple points out, however, that the base of the east wall of the pu'uhonua extended under the platform built in 1902 and that human bones have been found in other portions of the Great Wall and in similar cavities in the 'Ale'ale'a Heiau platform. Again, these are considered intrusive, historic-period burials.

e) Hale o Lono His 1919 informant mentioned to Stokes that on Lot 20 mauka of Hale-o-Keawe there existed a house referred to as "Hale o Lono." It stood on a low platform about twenty-one feet from the mauka wall of the refuge and extended east for about fifty feet. Its width was about twenty-five feet. According to this person, tidal waves had destroyed the platform many years earlier. He described the Hale-o-Lono as being a portion or continuation of the Hale-o-Keawe platform. At the time of that interview, he said the site was on the waterfront, partly encroached upon by a recently planted coconut grove. The house on the platform had been of ohi'a posts with ti leaf covering. It had a lanai on the front facing the sea on the north, as well as four doors in the front, four in back, and one at either end. South of this structure was a small house where Keawe kept his coconuts. f) Decline of the Mausoleum After 1829, maintenance of the Hale-o-Keawe ceased and it was left to the ravages of decay and natural forces. The structure had disappeared by 1851. Tidal waves and high seas over successive years damaged the masonry platform as well as the adjacent pu'uhonua walls. By 1902 those actions had reduced the platform and nearby area to a heap of rubble. The 1902 restoration work is considered fairly inaccurate, based solely on limited and questionable oral information. Hawai'i County crews performed further repair and maintenance work in the vicinity of the platform after the county leased the refuge as a park in the 1920s. g) The NPS Undertakes Reconstruction of the Mausoleum In 1963 the NPS decided to reconstruct for the first time a building associated with ancient Hawaiian culture. No guidelines or precedents existed for such a project. The major problem revolved around trying to build an authentic thatched house, a structural style virtually unknown to modern-day Hawaiians. Data gathering included a literature search for structural data in the Bishop Museum in an attempt to find specific data on the Hale-o-Keawe as well as general information on Hawaiian structures. Specific construction details needed for the temple were supplied using the general body of information about Hawaiian structures that had been assembled. The federal government funded several studies to learn more about Hale-o-Keawe, its physical development and its purpose. One was the Natural and Cultural History of Honaunau mentioned earlier, done in 1957 under contract to the Bishop Museum. Park Service employees also undertook a number of studies. Russell Apple analyzed both ethnohistorical and historical data for a pre-restoration study in 1966, and Edmund Ladd conducted a pre-salvage report in 1969, having completed excavations and restoration on the platform in 1967. Ladd discovered the original dry masonry platform side and top, which he restored, plus adjacent features. He found that Wall had fortunately not disturbed any of the underlying foundations of the prehistoric structure but had actually protected them by adding platforms to the side, front, and top. Although there had been disagreement among early visitors as to the actual size and location of the temple platform, Ladd found outlines of the original platform and its upper surface and was able to establish the approximate dimensions and orientation of the temple on it. The Ellis drawing was selected as the truest depiction of the structure. The complete restoration of the complex included the ti leaf thatched temple, carved images, an elevated altar, and a wooden palisade. This work, combined with Ladd's restored platform, seawalls, and nearby terrain resulted in a major interpretive feature at the park. The surface restoration project began August 28, 1967, and ended June 28, 1968. At the same time a small model of the Hale was built in 1968 to show the public how the temple was constructed. Over the next few years, the wooden images and palisades deteriorated to the extent that a second reconstruction was needed by 1982. That project included a new framework for the temple, rethatching with dried ti leaves, recarving of images, and replacement of the palisade. 4. Hale o Puni Stokes mentioned a pile of rubble immediately west of the Hale-o-Keawe that, when cleared, revealed edges of a rectangular platform. Some informants told him that was the site of the priests' quarters. Notes from Stokes's interview with a local informant suggest that makai of the Hale-o-Keawe terraces there formerly existed a large stone platform fenced with kauila posts "of such a height that they obscured the view of the Hale O Keawe from the west." The posts supposedly kept the platform stones in position. Chiefs and their families used the platform for social activities (possibly as entertainment structures where boxing or wrestling, for instance, could be watched by an audience seated on the surrounding ground). 5. "Old Heiau ("Ancient Heiau) The Reverend William Ellis in 1823 briefly mentioned the presence of three large heiau within the pu'uhonua, two being "considerably demolished" and the other "nearly entire." It has been assumed that the latter was 'Ale'ale'a Heiau, raising the question of whether the "Old Heiau" originally comprised one or two structures. Stokes recorded that

While investigating the ruins at Honaunau in 1919, Stokes subsequently made test excavations in the "Old Heiau" mound in an attempt to determine the original plan and configuration of the structure. This endeavor met with only limited success. Stokes did conclude that at least one large platform, 110 by 320 feet, and possibly a smaller one to the north, 28 by 60 feet, had once stood on the site. It was originally thought that this platform was the oldest structure in the pu'uhonua and that some of its stones later were used for construction of the 'Ale'ale'a temple. Later archeological excavations, however, have suggested that one of the first stages of 'Ale'ale'a might be the earliest temple site associated with the refuge. The "Old Heiau" was also constructed using the typical Hawaiian method of dry-laid unmodified blocks of lava rock. Stokes in 1919 performed some inspection of surface features. During World War II, the Hawai'i Home Guard, stationed on the nearby beach, may have modified the structure to some extent. The "Old Heiau" apparently lay neglected after its initial abandonment. Gradually the walls and platforms fell and covered the foundations of the entire structure, turning it into a pile of rubble and sand through which could be seen only dimly sections of walls, foundations, and pavement. In 1975 it was noted that surf and high waves during periods of turbulent seas constantly pounded the rubble mound. These activities, combined with visitor impacts, were causing the structure to lose its information potential at an alarming rate. Consequently it was decided to speed efforts to collect data and artifacts to support the park's interpretive programs and to preserve the structure through stabilization. The National Park Service, under the supervision of Edmund Ladd, mapped and excavated the "Old Heiau" site from September 1979 to September 1980. Relatively few artifacts were found, none of which provided much information on the site. Features found that appeared to have been original included wall faces; an interior platform facing; remnants of stone pavements; indications of a second, smaller, interior platform showing areas of pao construction; and walls of another, smaller enclosure north of the main one. Ladd determined that the site comprised two walled enclosures, the larger one containing two smaller platforms. He believed the form of the site to be similar to that of a luakini — a walled enclosure containing terraces, platforms, and other structures. He noted that it was similar in size and shape to that of Mo'okini in Kohala District and that its internal features, such as the possible raised interior terrace found, appeared similar to those thought to have been present at Pu'ukohola. In addition, radiocarbon dates corresponding to the construction period of the earliest luakini in Hawai'i; the predominance of pig faunal remains, indicating dedication rites associated with a luakini; and the finding that the first construction stage of 'Ale'ale'a Heiau probably pre-dated the "Old Heiau" suggesting the latter's construction on a site formerly built upon by the "people of old," all persuaded Ladd that his theory was correct. While 'Ale'ale'a might be older, it is better preserved because it continued to be used, while the "Old Heiau" was abandoned and severely impacted by surf action.