|

|

Hawaiian

Girl of the Old Régime.

Hawaiian Folk Tales, A Collection

of Native Legends

Compiled by Thos.

G. Thrum

With

sixteen illustrations from photographs

Chicago, A. C. McClurg & Co., 1907

Preface

It is becoming more and more a matter of

regret that a larger amount of systematic effort was not

established in early years for the gathering and preservation of the

folk-lore of the Hawaiians. The world is under lasting obligations to

the late Judge Fornander, and to Dr. Rae before him, for their

painstaking efforts to gather the history of this people and trace their

origin and migrations; but Fornander’s work only has seen the light, Dr.

Rae’s manuscript having been accidentally destroyed by fire.

The early attempts of Dibble and Pogue to

gather history from Hawaiians themselves have preserved to native and

foreign readers much that would probably otherwise have been lost. To

the late Judge Andrews we are indebted for a very full grammar and

dictionary of the language, as also for a valuable manuscript collection

of meles and antiquarian literature that passed to the custody of the

Board of Education.

There were native historians in those days;

the newspaper articles of S. M. Kamakau, the earlier writings of David

Malo, and the later contributions of G. W. Pilipo and others are but

samples of a wealth of material, most of which has been lost forever to

the world. From time to time Prof. W. D. Alexander, [vi]as also C. J.

Lyons, has furnished interesting extracts from these and other hakus.

The Rev. A. O. Forbes devoted some time and

thought to the collecting of island folk-lore: and King Kalakaua took

some pains in this line also, as evidenced by his volume of “Legends and

Myths of Hawaii,” edited by R. M. Daggett, though there is much therein

that is wholly foreign to ancient Hawaiian customs and thought. No one

of late years had a better opportunity than Kalakaua toward collecting

the meles, kaaos, and traditions of his race; and for purposes looking

to this end there was established by law a Board of Genealogy, which had

an existence of some four years, but nothing of permanent value resulted

therefrom.

Fornander’s manuscript collection of meles,

legends, and genealogies in the vernacular has fortunately become, by

purchase, the property of the Hon. C. R. Bishop, which insures for

posterity the result of one devoted scholar’s efforts to rescue the

ancient traditions that are gradually slipping away; for the haku meles

(bards) of Hawaii are gone. This fact, as also the Hawaiian Historical

Society’s desire to aid and stimulate research into the history and

traditions of this people, strengthens the hope that some one may yet

arise to give us further insight into the legendary folk-lore of this

interesting race. T. G. T., Honolulu, January 1, 1907.

Note

In response

to repeated requests, the compiler now presents in book form the series

of legends that have been made a feature of “The Hawaiian Annual” for a

number of years past. The series has been enriched by the addition of

several tales, the famous shark legend having been furnished for this

purpose from the papers of the Hawaiian Historical Society.

The collection embraces contributions by the

Rev. A. O. Forbes, Dr. N. B. Emerson, J. S. Emerson, Mrs. E. M. Nakuina,

W. M. Gibson, Dr. C. M. Hyde, and others, all of whom are recognized

authorities.

Legends

Resembling Old Testament History

Exploits of Maui

Snaring the Sun

The Origin of Fire

Pele and the Deluge

Pele and

Kahawali

Hiku and Kawelu

Location of the Lua o Milu

Lonopuha; or, Origin

of the Art of Healing in Hawaii

A Visit to the

Spirit Land; or, The Strange Experience of a Woman in Kona, Hawaii

Kapeepeekauila; or, The Rocks of Kana

Kalelealuaka

Stories of the

Menehunes: Hawaii the Original Home of the Brownies

Moke Manu’s Account

Pi’s Watercourse

Laka’s Adventure

Kekupua’s Canoe

As Heiau Builders

Kahalaopuna,

Princess of Manoa

Ahuula: A Legend of

Kanikaniaula and the First Feather Cloak

Kaala and Kaaialii: A

Legend of Lanai

The Tomb of Puupehe:

A Legend of Lanai

Ai Kanaka: A Legend

of Molokai

Kaliuwaa. Scene of

the Demigod Kamapuaa’s Escape from Olopana

Battle of the Owls

This Land is

the Sea’s. Traditional Account of an Ancient Hawaiian Prophecy

Ku-ula, the Fish God

of Hawaii

Aiai, Son of Ku-ula.

Part II of the Legend of Ku-ula, the Fish God of Hawaii

Kaneaukai: A Legend

of Waialua

The Shark-man,

Nanaue

Legends Resembling

Old Testament History, Rev. C. M. Hyde, D.D.

In the first volume of Judge Fornander’s

elaborate work on “The Polynesian Race” he has given some old Hawaiian

legends which closely resemble the Old Testament history. How shall we

account for such coincidences?

Take, for instance, the Hawaiian account of

the Creation. The Kane, Ku and Lono: or, Sunlight, Substance, and

Sound,—these constituted a triad named Ku-Kaua-Kahi, or the Fundamental

Supreme Unity. In worship the reverence due was expressed by such

epithets as Hi-ka-po-loa, Oi-e, Most Excellent, etc. “These gods existed

from eternity, from and before chaos, or, as the Hawaiian term expressed

it, ‘mai ka po mia’ (from the time of night, darkness, chaos). By an act

of their will these gods dissipated or broke into pieces the existing,

surrounding, all-containing po, night, or chaos. By this act light

entered into space. They then created the heavens, three in number, as a

place to dwell in; and the earth to be their footstool, he keehina honua

a Kane. Next they created the sun, moon, stars, and a host of angels, or

spirits—i kini akua—to minister to them. Last of all they created man as

the model, or in the likeness of Kane. The body of the first man was

made of red earth—lepo ula, or alaea—and the spittle of the gods—wai nao.

His head was made of a whitish clay—palolo—which was brought from the

four ends of the world by Lono. When the earth-image of Kane was ready,

the three gods breathed into its nose, and called on it to rise, and it

became a living being. Afterwards the first woman was created from one

of the ribs—lalo puhaka—of the man while asleep, and these two were the

progenitors of all mankind. They are called in the chants and in various

legends by a large number of different names; but the most common for

the man was Kumuhonua, and for the woman Keolakuhonua [or Lalahonua].

“Of the creation of animals these chants are

silent; but from the pure tradition it may be inferred that the earth at

the time of its creation or emergence from the watery chaos was stocked

with vegetable and animal. The animals specially mentioned in the

tradition as having been created by Kane were hogs (puaa), dogs (ilio),

lizards or reptiles (moo).

“Another legend of the series, that of

Wela-ahi-lani, states that after Kane had destroyed the world by fire,

on account of the wickedness of the people then living, he organized it

as it now is, and created the first man and the first woman, with the

assistance of Ku and Lono, nearly in the same manner as narrated in the

former legend of Kumuhonua. In this legend the man is called

Wela-ahi-lani, and the woman is called Owe.”

Of the primeval home, the original ancestral

seat of mankind, Hawaiian traditions speak in highest praise. “It had a

number of names of various meanings, though the most generally

occurring, and said to be the oldest, was Kalana-i-hau-ola (Kalana with

the life-giving dew). It was situated in a large country, or continent,

variously called in the legends Kahiki-honua-kele, Kahiki-ku, Kapa-kapa-ua-a-Kane,

Molo-lani. Among other names for the primary homestead, or paradise, are

Pali-uli (the blue mountain), Aina-i-ka-kaupo-o-Kane (the land in the

heart of Kane), Aina-wai-akua-a-Kane (the land of the divine water of

Kane). The tradition says of Pali-uli, that it was a sacred, tabooed

land; that a man must be righteous to attain it; if faulty or sinful he

will not get there; if he looks behind he will not get there; if he

prefers his family he will not enter Pali-uli.” “Among other adornments

of the Polynesian Paradise, the Kalana-i-hau-ola, there grew the Ulu

kapu a Kane, the breadfruit tabooed for Kane, and the ohia hemolele, the

sacred apple-tree. The priests of the olden time are said to have held

that the tabooed fruits of these trees were in some manner connected

with the trouble and death of Kumuhonua and Lalahonua, the first man and

the first woman. Hence in the ancient chants he is called Kane-laa-uli,

Kumu-uli, Kulu-ipo, the fallen chief, he who fell on account of the

tree, or names of similar import.”

According to those legends of Kumuhonua and

Wela-ahi-lani, “at the time when the gods created the stars, they also

created a multitude of angels, or spirits (i kini akua), who were not

created like men, but made from the spittle of the gods (i kuhaia), to

be their servants or messengers. These spirits, or a number of them,

disobeyed and revolted, because they were denied the awa; which means

that they were not permitted to be worshipped, awa being a sacrificial

offering and sign of worship. These evil spirits did not prevail,

however, but were conquered by Kane, and thrust down into uttermost

darkness (ilalo loa i ka po). The chief of these spirits was called by

some Kanaloa, by others Milu, the ruler of Po; Akua ino; Kupu ino, the

evil spirit. Other legends, however, state that the veritable and

primordial lord of the Hawaiian inferno was called Manua. The inferno

itself bore a number of names, such as Po-pau-ole, Po-kua-kini, Po-kini-kini,

Po-papa-ia-owa, Po-ia-milu. Milu, according to those other legends, was

a chief of superior wickedness on earth who was thrust down into Po, but

who was really both inferior and posterior to Manua. This inferno, this

Po, with many names, one of which remarkably enough was Ke-po-lua-ahi,

the pit of fire, was not an entirely dark place. There was light of some

kind and there was fire. The legends further tell us that when Kane, Ku,

and Lono were creating the first man from the earth, Kanaloa was

present, and in imitation of Kane, attempted to make another man out of

the earth. When his clay model was ready, he called to it to become

alive, but no life came to it. Then Kanaloa became very angry, and said

to Kane, ‘I will take your man, and he shall die,’ and so it happened.

Hence the first man got his other name Kumu-uli, which means a fallen

chief, he ’lii kahuli.... With the Hawaiians, Kanaloa is the personified

spirit of evil, the origin of death, the prince of Po, or chaos, and yet

a revolted, disobedient spirit, who was conquered and punished by Kane.

The introduction and worship of Kanaloa, as one of the great gods in the

Hawaiian group, can be traced back only to the time of the immigration

from the southern groups, some eight hundred years ago. In the more

ancient chants he is never mentioned in conjunction with Kane, Ku, and

Lono, and even in later Hawaiian mythology he never took precedence of

Kane. The Hawaiian legend states that the oldest son of Kumuhonua, the

first man, was called Laka, and that the next was called Ahu, and that

Laka was a bad man; he killed his brother Ahu.

“There are these different Hawaiian

genealogies, going back with more or less agreement among themselves to

the first created man. The genealogy of Kumuhonua gives thirteen

generations inclusive to Nuu, or Kahinalii, or the line of Laka, the

oldest son of Kumuhonua. (The line of Seth from Adam to Noah counts ten

generations.) The second genealogy, called that of Kumu-uli, was of

greatest authority among the highest chiefs down to the latest times,

and it was taboo to teach it to the common people. This genealogy counts

fourteen generations from Huli-houna, the first man, to Nuu, or Nana-nuu,

but inclusive, on the line of Laka. The third genealogy, which, properly

speaking, is that of Paao, the high-priest who came with Pili from

Tahiti, about twenty-five generations ago, and was a reformer of the

Hawaiian priesthood, and among whose descendants it has been preserved,

counts only twelve generations from Kumuhonua to Nuu, on the line of

Kapili, youngest son of Kumuhonua.”

“In the Hawaiian group there are several

legends of the Flood. One legend relates that in the time of Nuu, or

Nana-nuu (also pronounced lana, that is, floating), the flood,

Kaiakahinalii, came upon the earth, and destroyed all living beings;

that Nuu, by command of his god, built a large vessel with a house on

top of it, which was called and is referred to in chants as ‘He waa

halau Alii o ka Moku,’ the royal vessel, in which he and his family,

consisting of his wife, Lilinoe, his three sons and their wives, were

saved. When the flood subsided, Kane, Ku, and Lono entered the waa halau

of Nuu, and told him to go out. He did so, and found himself on the top

of Mauna Kea (the highest mountain on the island of Hawaii). He called a

cave there after the name of his wife, and the cave remains there to

this day—as the legend says in testimony of the fact. Other versions of

the legend say that Nuu landed and dwelt in Kahiki-honua-kele, a large

and extensive country.” ... “Nuu left the vessel in the evening of the

day and took with him a pig, cocoanuts, and awa as an offering to the

god Kane. As he looked up he saw the moon in the sky. He thought it was

the god, saying to himself, ‘You are Kane, no doubt, though you have

transformed yourself to my sight.’ So he worshipped the moon, and

offered his offerings. Then Kane descended on the rainbow and spoke

reprovingly to Nuu, but on account of the mistake Nuu escaped

punishment, having asked pardon of Kane.” ... “Nuu’s three sons were

Nalu-akea, Nalu-hoo-hua, and Nalu-mana-mana. In the tenth generation

from Nuu arose Lua-nuu, or the second Nuu, known also in the legend as

Kane-hoa-lani, Kupule, and other names. The legend adds that by command

of his god he was the first to introduce circumcision to be practised

among his descendants. He left his native home and moved a long way off

until he reached a land called Honua-ilalo, ‘the southern country.’

Hence he got the name Lalo-kona, and his wife was called Honua-po-ilalo.

He was the father of Ku-nawao by his slave-woman Ahu (O-ahu) and of

Kalani-menehune by his wife, Mee-hewa. Another says that the god Kane

ordered Lua-nuu to go up on a mountain and perform a sacrifice there.

Lua-nuu looked among the mountains of Kahiki-ku, but none of them

appeared suitable for the purpose. Then Lua-nuu inquired of God where he

might find a proper place. God replied to him: ‘Go travel to the

eastward, and where you find a sharp-peaked hill projecting

precipitously into the ocean, that is the hill for the sacrifice.’ Then

Lua-nuu and his son, Kupulu-pulu-a-Nuu, and his servant, Pili-lua-nuu,

started off in their boat to the eastward. In remembrance of this event

the Hawaiians called the back of Kualoa Koo-lau; Oahu (after one of

Lua-nuu’s names), Kane-hoa-lani; and the smaller hills in front of it

were named Kupu-pulu and Pili-lua-nuu. Lua-nuu is the tenth descendant

from Nuu by both the oldest and the youngest of Nuu’s sons. This oldest

son is represented to have been the progenitor of the Kanaka-maoli, the

people living on the mainland of Kane (Aina kumupuaa a Kane): the

youngest was the progenitor of the white people (ka poe keo keo maoli).

This Lua-nuu (like Abraham, the tenth from Noah, also like Abraham),

through his grandson, Kini-lau-a-mano, became the ancestor of the twelve

children of the latter, and the original founder of the Menehune people,

from whom this legend makes the Polynesian family descend.”

The Rev. Sheldon Dibble, in his history of

the Sandwich Islands, published at Lahainaluna, in 1843, gives a

tradition which very much resembles the history of Joseph.

“Waikelenuiaiku was one of ten brethren who had one sister. They were

all the children of one father, whose name was Waiku. Waikelenuiaiku was

much beloved by his father, but his brethren hated him. On account of

their hatred they carried him and cast him into a pit belonging to

Holonaeole. The oldest brother had pity on him, and gave charge to

Holonaeole to take good care of him. Waikelenuiaiku escaped and fled to

a country over which reigned a king whose name was Kamohoalii. There he

was thrown into a dark place, a pit under ground, in which many persons

were confined for various crimes. Whilst confined in this dark place he

told his companions to dream dreams and tell them to him. The night

following four of the prisoners had dreams. The first dreamed that he

saw a ripe ohia (native apple), and his spirit ate it; the second

dreamed that he saw a ripe banana, and his spirit ate it; the third

dreamed that he saw a hog, and his spirit ate it; and the fourth dreamed

that he saw awa, pressed out the juice, and his spirit drank it. The

first three dreams, pertaining to food, Waikelenuiaiku interpreted

unfavorably, and told the dreamers they must prepare to die. The fourth

dream, pertaining to drink, he interpreted to signify deliverance and

life. The first three dreamers were slain according to the

interpretation, and the fourth was delivered and saved. Afterward this

last dreamer told Kamohoalii, the king of the land, how wonderful was

the skill of Waikelenuiaiku in interpreting dreams, and the king sent

and delivered him from prison and made him a principal chief in his

kingdom.”

Judge Fornander alludes to this legend,

giving the name, however, Aukelenui-a-Iku, and adding to it the account

of the hero’s journey to the place where the water of life was kept (ka-wai-ola-loa-a-Kane),

his obtaining it and therewith resuscitating his brothers, who had been

killed by drowning some years before. Another striking similarity is

that furnished to Judge Fornander in the legend of Ke-alii-waha-nui: “He

was king of the country called Honua-i-lalo. He oppressed the Menehune

people. Their god Kane sent Kane-apua and Kaneloa, his elder brother, to

bring the people away, and take them to the land which Kane had given

them, and which was called Ka aina momona a Kane, or Ka one lauena a

Kane, and also Ka aina i ka haupo a Kane. The people were then told to

observe the four Ku days in the beginning of the month as Kapu-hoano

(sacred or holy days), in remembrance of this event, because they thus

arose (Ku) to depart from that land. Their offerings on the occasion

were swine and goats.” The narrator of the legend explains that formerly

there were goats without horns, called malailua, on the slopes of Mauna

Loa on Hawaii, and that they were found there up to the time of

Kamehameha I. The legend further relates that after leaving the land of

Honualalo, the people came to the Kai-ula-a-Kane (the Red Sea of Kane);

that they were pursued by Ke-alii-waha-nui; that Kane-apua and Kanaloa

prayed to Lono, and finally reached the Aina lauena a Kane.

“In the famous Hawaiian legend of

Hiiaka-i-ka-poli-o-Pele, it is said that when Hiiaka went to the island

of Kauai to recover and restore to life the body of Lohiau, the lover of

her sister, Pele, she arrived at the foot of the Kalalau Mountain

shortly before sunset. Being told by her friends at Haena that there

would not be daylight sufficient to climb the pali (precipice) and get

the body out of the cave in which it was hidden, she prayed to her gods

to keep the sun stationary (i ka muli o Hea) over the brook Hea, until

she had accomplished her object. The prayer was heard, the mountain was

climbed, the guardians of the cave vanquished, and the body recovered.”

A story of retarding the sun and making the

day longer to accomplish his purpose is told of Maui-a-kalana, according

to Dibble’s history.

Judge Fornander alludes to one other legend

with incidents similar to the Old Testament history wherein

“Na-ula-a-Mainea, an Oahu prophet, left Oahu for Kauai, was upset in his

canoe, was swallowed by a whale, and thrown up alive on the beach at

Wailua, Kauai.”

Judge Fornander says that, when he first

heard the legend of the two brother prophets delivering the Menehune

people, “he was inclined to doubt its genuineness and to consider it as

a paraphrase or adaptation of the Biblical account by some

semi-civilized or semi-Christianized Hawaiian, after the discovery of

the group by Captain Cook. But a larger and better acquaintance with

Hawaiian folk-lore has shown that though the details of the legend, as

interpreted by the Christian Hawaiian from whom it was received, may

possibly in some degree, and unconsciously to him, perhaps, have

received a Biblical coloring, yet the main facts of the legend, with the

identical names of persons and places, are referred to more or less

distinctly in other legends of undoubted antiquity.” And the Rev. Mr.

Dibble, in his history, says of these Hawaiian legends, that “they were

told to the missionaries before the Bible was translated into the

Hawaiian tongue, and before the people knew much of sacred history. The

native who acted as assistant in translating the history of Joseph was

forcibly struck with its similarity to their ancient tradition. Neither

is there the least room for supposing that the songs referred to are

recent inventions. They can all be traced back for generations, and are

known by various persons residing on different islands who have had no

communication with each other. Some of them have their date in the reign

of some ancient king, and others have existed time out of mind. It may

also be added, that both their narrations and songs are known the best

by the very oldest of the people, and those who never learned to read;

whose education and training were under the ancient system of

heathenism.”

“Two hypotheses,” says Judge Fornander, “may

with some plausibility be suggested to account for this remarkable

resemblance of folk-lore. One is, that during the time of the Spanish

galleon trade, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, between the

Spanish Main and Manila, some shipwrecked people, Spaniards and

Portuguese, had obtained sufficient influence to introduce these scraps

of Bible history into the legendary lore of this people.... On this fact

hypothesis I remark that, if the shipwrecked foreigners were educated

men, or only possessed of such Scriptural knowledge as was then imparted

to the commonality of laymen, it is morally impossible to conceive that

a Spaniard of the sixteenth century should confine his instruction to

some of the leading events of the Old Testament, and be totally silent

upon the Christian dispensation, and the cruciolatry, mariolatry, and

hagiolatry of that day. And it is equally impossible to conceive that

the Hawaiian listeners, chiefs, priests, or commoners, should have

retained and incorporated so much of the former in their own folk-lore,

and yet have utterly forgotten every item bearing upon the latter.

“The other hypothesis is, that at some

remote period either a body of the scattered Israelites had arrived at

these islands direct, or in Malaysia, before the exodus of ‘the

Polynesian family,’ and thus imparted a knowledge of their doctrines, of

the early life of their ancestors, and of some of their peculiar

customs, and that having been absorbed by the people among whom they

found a refuge, this is all that remains to attest their

presence—intellectual tombstones over a lost and forgotten race, yet

sufficient after twenty-six centuries of silence to solve in some

measure the ethnic puzzle of the lost tribes of Israel. In regard to

this second hypothesis, it is certainly more plausible and cannot be so

curtly disposed of as the Spanish theory.... So far from being copied

one from the other, they are in fact independent and original versions

of a once common legend, or series of legends, held alike by Cushite,

Semite, Turanian, and Aryan, up to a certain time, when the divergencies

of national life and other causes brought other subjects peculiar to

each other prominently in the foreground; and that as these divergencies

hardened into system and creed, that grand old heirloom of a common past

became overlaid and colored by the peculiar social and religious

atmosphere through which it has passed up to the surface of the present

time. But besides this general reason for refusing to adopt the

Israelitish theory, that the Polynesian legends were introduced by

fugitive or emigrant Hebrews from the subverted kingdoms of Israel or

Judah, there is the more special reason to be added that the

organization and splendor of Solomon’s empire, his temple, and his

wisdom became proverbial among the nations of the East subsequent to his

time; on all these, the Polynesian legends are absolutely silent.”

In commenting on the legend of

Hiiaka-i-ka-poli-o-Pele, Judge Fornander says: “If the Hebrew legend of

Joshua or a Cushite version give rise to it, it only brings down the

community of legends a little later in time. And so would the legend of

Naulu-a-Mahea,... unless the legend of Jonah, with which it corresponds

in a measure, as well as the previous legend of Joshua and the sun, were

Hebrew anachronisms compiled and adapted in later times from long

antecedent materials, of which the Polynesian references are but broken

and distorted echoes, bits of legendary mosaics, displaced from their

original surroundings and made to fit with later associations.”

In regard to the account of the Creation, he

remarks that “the Hebrew legend infers that the god Elohim existed

contemporaneously with and apart from the chaos. The Hawaiian legend

makes the three great gods, Kane, Ku, and Lono, evolve themselves out of

chaos.... The order of creation, according to Hawaiian folk-lore, was

that after Heaven and earth had been separated, and the ocean had been

stocked with its animals, the stars were created, then the moon, then

the sun.” Alluding to the fact that the account in Genesis is truer to

nature, Judge Fornander nevertheless propounds the inquiry whether this

fact may not “indicate that the Hebrew text is a later emendation of an

older but once common tradition”?

Highest antiquity is claimed for Hawaiian

traditions in regard to events subsequent to the creation of man. “In

one of the sacrificial hymns of the Marquesans, when human victims were

offered, frequent allusions were made to ‘the red apples eaten in Naoau,’

... and to the ‘tabooed apples of Atea,’ as the cause of death, wars,

pestilence, famine, and other calamities, only to be averted or atoned

for by the sacrifice of human victims. The close connection between the

Hawaiian and the Marquesan legends indicates a common origin, and that

origin can be no other than that from which the Chaldean and Hebrew

legends of sacred trees, disobedience, and fall also sprang.” In

comparison of “the Hawaiian myth of Kanaloa as a fallen angel

antagonistic to the great gods, as the spirit of evil and death in the

world, the Hebrew legends are more vague and indefinite as to the

existence of an evil principle. The serpent of Genesis, the Satan of

Job, the Hillel of Isaiah, the dragon of the Apocalypse—all point,

however, to the same underlying idea that the first cause of sin, death,

evil, and calamities, was to be found in disobedience and revolt from

God. They appear as disconnected scenes of a once grand drama that in

olden times riveted the attention of mankind, and of which, strange to

say, the clearest synopsis and the most coherent recollection are, so

far, to be found in Polynesian traditions. It is probably in vain to

inquire with whom the legend of an evil spirit and his operations in

Heaven and on earth had its origin. Notwithstanding the apparent unity

of design and remarkable coincidence in many points, yet the differences

in coloring, detail, and presentation are too great to suppose the

legend borrowed by one from either of the others. It probably descended

to the Chaldeans, Polynesians, and Hebrews alike, from a source or

people anterior to themselves, of whom history now is silent.”

Back to Contents

Exploits of Maui,

Rev. A. O. Forbes

Snaring the Sun

Maui was the son of Hina-lau-ae

and Hina, and they dwelt at a place called Makalia, above Kahakuloa, on

West Maui. Now, his mother Hina made kapas. And as she spread them out

to dry, the days were so short that she was put to great trouble and

labor in hanging them out and taking them in day after day until they

were dry. Maui, seeing this, was filled with pity for her, for the days

were so short that, no sooner had she got her kapas all spread out to

dry, than the Sun went down, and she had to take them in again. So he

determined to make the Sun go slower. He first went to Wailohi, in

Hamakua, on East Maui, to observe the motions of the Sun. There he saw

that it rose toward Hana. He then went up on Haleakala, and saw that the

Sun in its course came directly over that mountain. He then went home

again, and after a few days went to a place called Paeloko, at Waihee.

There he cut down all the cocoanut-trees, and gathered the fibre of the

cocoanut husks in great quantity. This he manufactured into strong cord.

One Moemoe, seeing this, said tauntingly to him: “Thou wilt never catch

the Sun. Thou art an idle nobody.”

Maui answered: “When I conquer my enemy, and

my desire is attained, I will be your death.” So he went up Haleakala

again, taking his cord with him. And when the Sun arose above where he

was stationed, he prepared a noose of the cord and, casting it, snared

one of the Sun’s larger beams and broke it off. And thus he snared and

broke off, one after another, all the strong rays of the Sun.

Then shouted he exultingly: “Thou art my

captive, and now I will kill thee for thy going so swiftly.”

And the Sun said: “Let me live, and thou

shalt see me go more slowly hereafter. Behold, hast thou not broken off

all my strong legs, and left me only the weak ones?”

So the agreement was made, and Maui

permitted the Sun to pursue its course, and from that time on it went

more slowly; and that is the reason why the days are longer at one

season of the year than at another. It was this that gave the name to

that mountain, which should properly be called Alehe-ka-la (sun snarer),

and not Haleakala.

When Maui returned from this exploit, he

went to find Moemoe, who had reviled him. But that individual was not at

home. He went on in his pursuit till he came upon him at a place called

Kawaiopilopilo, on the shore to the eastward of the black rock called

Kekaa, north of Lahaina. Moemoe dodged him up hill and down, until at

last Maui, growing wroth, leaped upon and slew the fugitive. And the

dead body was transformed into a long rock, which is there to this day,

by the side of the road.

The Origin of Fire

Maui and Hina dwelt together, and to them

were born four sons, whose names were Maui-mua, Maui-hope, Maui-kiikii,

and Maui-o-ka-lana. These four were fishermen. One morning, just as the

edge of the Sun lifted itself up, Maui-mua roused his brethren to go

fishing. So they launched their canoe from the beach at Kaupo, on the

island of Maui, where they were dwelling, and proceeded to the fishing

ground. Having arrived there, they were beginning to fish, when

Maui-o-ka-lana saw the light of a fire on the shore they had left, and

said to his brethren: “Behold, there is a fire burning. Whose can this

fire be?”

And they answered: “Whose, indeed? Let us

return to the shore, that we may get our food cooked; but first let us

get some fish.”

So, after they had obtained some fish, they

turned toward the shore; and when the canoe touched the beach Maui-mua

leaped ashore and ran toward the spot where the fire had been burning.

Now, the curly-tailed alae (mud-hens) were the keepers of the fire; and

when they saw him coming they scratched the fire out and flew away.

Maui-mua was defeated, and returned to the house to his brethren.

Then said they to him: “How about the fire?”

“How, indeed?” he answered. “When I got

there, behold, there was no fire; it was out. I supposed some man had

the fire, and behold, it was not so; the alae are the proprietors of the

fire, and our bananas are all stolen.”

When they heard that, they were filled with

anger, and decided not to go fishing again, but to wait for the next

appearance of the fire. But after many days had passed without their

seeing the fire, they went fishing again, and behold, there was the

fire! And so they were continually tantalized. Only when they were out

fishing would the fire appear, and when they returned they could not

find it.

This was the way of it. The curly-tailed

alae knew that Maui and Hina had only these four sons, and if any of

them stayed on shore to watch the fire while the others were out in the

canoe the alae knew it by counting those in the canoe, and would not

light the fire. Only when they could count four men in the canoe would

they light the fire. So Maui-mua thought it over, and said to his

brethren: “To-morrow morning do you go fishing, and I will stay ashore.

But do you take the calabash and dress it in kapa, and put it in my

place in the canoe, and then go out to fish.”

They did so, and when they went out to fish

the next morning, the alae counted and saw four figures in the canoe,

and then they lit the fire and put the bananas on to roast. Before they

were fully baked one of the alae cried out: “Our dish is cooked! Behold,

Hina has a smart son.”

And with that, Maui-mua, who had stolen

close to them unperceived, leaped forward, seized the curly-tailed alae

and exclaimed: “Now I will kill you, you scamp of an alae! Behold, it is

you who are keeping the fire from us. I will be the death of you for

this.”

Then answered the alae: “If you kill me the

secret dies with me, and you won’t get the fire.” As Maui-mua began to

wring its neck, the alae again spoke, and said: “Let me live, and you

shall have the fire.”

So Maui-mua said: “Tell me, where is the

fire?”

The alae replied: “It is in the leaf of the

a-pe plant” (Alocasia macrorrhiza).

So, by the direction of the alae, Maui-mua

began to rub the leaf-stalk of the a-pe plant with a piece of stick, but

the fire would not come. Again he asked: “Where is this fire that you

are hiding from me?”

The alae answered: “In a green stick.”

And he rubbed a green stick, but got no

fire. So it went on, until finally the alae told him he would find it in

a dry stick; and so, indeed, he did. But Maui-mua, in revenge for the

conduct of the alae, after he had got the fire from the dry stick, said:

“Now, there is one thing more to try.” And he rubbed the top of the

alae’s head till it was red with blood, and the red spot remains there

to this day. Back to Contents

Pele and the Deluge,

Rev. A. O. Forbes

All volcanic phenomena are associated in

Hawaiian legendary lore with the goddess Pele; and it is a somewhat

curious fact that to the same celebrated personage is also attributed a

great flood that occurred in ancient times. The legends of this flood

are various, but mainly connected with the doings of Pele in this part

of the Pacific Ocean. The story runs thus:

Kahinalii was the mother of Pele;

Kanehoalani was her father; and her two brothers were Kamohoalii and

Kahuilaokalani. Pele was born in the land of Hapakuela, a far-distant

land at the edge of the sky, toward the southwest. There she lived with

her parents until she was grown up, when she married Wahialoa; and to

these were born a daughter named Laka, and a son named Menehune. But

after a time Pele’s husband, Wahialoa, was enticed away from her by

Pele-kumulani. The deserted Pele, being much displeased and troubled in

mind on account of her husband, started on her travels in search of him,

and came in the direction of the Hawaiian Islands. Now, at that time

these islands were a vast waste. There was no sea, nor was there any

fresh water. When Pele set out on her journey, her parents gave her the

sea to go with her and bear her canoes onward. So she sailed forward,

flood-borne by the sea, until she reached the land of Pakuela, and

thence onward to the land of Kanaloa. From her head she poured forth the

sea as she went, and her brothers composed the celebrated ancient mele:

O the sea, the great sea!

Forth bursts the sea:

Behold, it bursts on Kanaloa!

But the waters of the sea continued to rise

until only the highest points of the great mountains, Haleakala,

Maunakea, and Maunaloa, were visible; all else was covered. Afterward

the sea receded until it reached its present level. This event is called

the Kai a Kahinalii (Sea of Kahinalii), because it was from Kahinalii,

her mother, that Pele received the gift of the sea, and she herself only

brought it to Hawaii.

And from that time to this, Pele and all her

family forsook their former land of Hapakuela and have dwelt in Hawaii-nei,

Pele coming first and the rest following at a later time.

On her first arrival at Hawaii-nei, Pele

dwelt on the island of Kauai. From there she went to Kalaupapa, on the

island of Molokai, and dwelt in the crater of Kauhako at that place;

thence she departed to Puulaina, near Lahainaluna, where she dug out

that crater. Afterward she moved still further to Haleakala, where she

stayed until she hollowed out that great crater; and finally she settled

at Kilauea, on the island of Hawaii, where she has remained ever since.

Back to Contents

In the reign of Kealiikukii, an ancient king

of Hawaii, Kahawali, chief of Puna, and one of his favorite companions

went one day to amuse themselves with the holua (sled), on the sloping

side of a hill, which is still called ka holua ana o Kahawali (Kahawali’s

sliding-place). Vast numbers of the people gathered at the bottom of the

hill to witness the game, and a company of musicians and dancers

repaired thither to add to the amusement of the spectators. The

performers began their dance, and amidst the sound of drums and the

songs of the musicians the sledding of Kahawali and his companion

commenced. The hilarity of the occasion attracted the attention of Pele,

the goddess of the volcano, who came down from Kilauea to witness the

sport. Standing on the summit of the hill in the form of a woman, she

challenged Kahawali to slide with her. He accepted the offer, and they

set off together down the hill. Pele, less acquainted with the art of

balancing herself on the narrow sled than her rival, was beaten, and

Kahawali was applauded by the spectators as he returned up the side of

the hill.

Before starting again, Pele asked him to

give her his papa holua, but he, supposing from her appearance that she

was no more than a native woman, said: “Aole! (no!) Are you my wife,

that you should obtain my sled?” And, as if impatient at being delayed,

he adjusted his papa, ran a few yards to take a spring, and then, with

this momentum and all his strength he threw himself upon it and shot

down the hill.

A Lava

Cascade.

Pele, incensed at his answer, stamped her

foot on the ground and an earthquake followed, which rent the hill in

sunder. She called, and fire and liquid lava arose, and, assuming her

supernatural form, with these irresistible ministers of vengeance, she

followed down the hill. When Kahawali reached the bottom, he arose, and

on looking behind saw Pele, accompanied by thunder and lightning,

earthquake, and streams of burning lava, closely pursuing him. He took

up his broad spear which he had stuck in the ground at the beginning of

the game, and, accompanied by his friend, fled for his life. The

musicians, dancers, and crowds of spectators were instantly overwhelmed

by the fiery torrent, which, bearing on its foremost wave the enraged

goddess, continued to pursue Kahawali and his companion. They ran till

they came to an eminence called Puukea. Here Kahawali threw off his

cloak of netted ki leaves and proceeded toward his house, which stood

near the shore. He met his favorite pig and saluted it by touching

noses, then ran to the house of his mother, who lived at Kukii, saluted

her by touching noses, and said: “Aloha ino oe, eia ihonei paha oe e

make ai, ke ai mainei Pele.” (Compassion great to you! Close here,

perhaps, is your death; Pele comes devouring.) Leaving her, he met his

wife, Kanakawahine, and saluted her. The burning torrent approached, and

she said: “Stay with me here, and let us die together.” He said: “No; I

go, I go.” He then saluted his two children, Poupoulu and Kaohe, and

said, “Ke ue nei au ia olua.” (I grieve for you two.) The lava rolled

near, and he ran till a deep chasm arrested his progress. He laid down

his spear and walked over on it in safety. His friend called out for his

help; he held out his spear over the chasm; his companion took hold of

it and he drew him securely over. By this time Pele was coming down the

chasm with accelerated motion. He ran till he reached Kula. Here he met

his sister, Koai, but had only time to say, “Aloha oe!” (Alas for you!)

and then ran on to the shore. His younger brother had just landed from

his fishing-canoe, and had hastened to his house to provide for the

safety of his family, when Kahawali arrived. He and his friend leaped

into the canoe, and with his broad spear paddled out to sea. Pele,

perceiving his escape, ran to the shore and hurled after him, with

prodigious force, great stones and fragments of rock, which fell thickly

around but did not strike his canoe. When he had paddled a short

distance from the shore the kumukahi (east wind) sprung up. He fixed his

broad spear upright in the canoe, that it might answer the double

purpose of mast and sail, and by its aid he soon reached the island of

Maui, where they rested one night and then proceeded to Lanai. The day

following they moved on to Molokai, thence to Oahu, the abode of

Kolonohailaau, his father, and Kanewahinekeaho, his sister, to whom he

related his disastrous perils, and with whom he took up his permanent

abode. Back to Contents

Hiku and Kawelu,

J. S. Emerson

Not far from

the summit of Hualalai, on the island of Hawaii, in the cave on the

southern side of the ridge, lived Hina and her son, the kupua, or

demigod, Hiku. All his life long as a child and a youth, Hiku had lived

alone with his mother on this mountain summit, and had never once been

permitted to descend to the plains below to see the abodes of men and to

learn of their ways. From time to time, his quick ear had caught the

sound of the distant hula (drum) and the voices of the gay merrymakers.

Often had he wished to see the fair forms of those who danced and sang

in those far-off cocoanut groves. But his mother, more experienced in

the ways of the world, had never given her consent. Now, at length, he

felt that he was a man, and as the sounds of mirth arose on his ears,

again he asked his mother to let him go for himself and mingle with the

people on the shore. His mother, seeing that his mind was made up to go,

reluctantly gave her consent and warned him not to stay too long, but to

return in good time. So, taking in his hand his faithful arrow, Pua Ne,

which he always carried, he started off.

This arrow was a sort of talisman, possessed

of marvellous powers, among which were the ability to answer his call

and by its flight to direct his journey.

Thus he descended over the rough clinker

lava and through the groves of koa that cover the southwestern flank of

the mountain, until, nearing its base, he stood on a distant hill; and

consulting his arrow, he shot it far into the air, watching its

bird-like flight until it struck on a distant hill above Kailua. To this

hill he rapidly directed his steps, and, picking up his arrow in due

time, he again shot it into the air. The second flight landed the arrow

near the coast of Holualoa, some six or eight miles south of Kailua. It

struck on a barren waste of pahoehoe, or lava rock, beside the waterhole

of Waikalai, known also as the Wai a Hiku (Water of Hiku), where to this

day all the people of that vicinity go to get their water for man and

beast.

Here he quenched his thirst, and nearing the

village of Holualoa, again shot the arrow, which, instinct with life,

entered the courtyard of the alii or chief, of Kona, and from among the

women who were there singled out the fair princess Kawelu, and landed at

her feet. Seeing the noble bearing of Hiku as he approached to claim his

arrow, she stealthily hid it and challenged him to find it. Then Hiku

called to the arrow, “Pua ne! Pua ne!” and the arrow replied, “Ne!” thus

revealing its hiding-place.

This exploit with the arrow and the

remarkable grace and personal beauty of the young man quite won the

heart of the princess, and she was soon possessed by a strong passion

for him, and determined to make him her husband.

With her wily arts she detained him for

several days at her home, and when at last he was about to start for the

mountain, she shut him up in the house and thus detained him by force.

But the words of his mother, warning him not to remain too long, came to

his mind, and he determined to break away from his prison. So he climbed

up to the roof, and removing a portion of the thatch, made his escape.

When his flight was discovered by Kawelu,

the infatuated girl was distracted with grief. Refusing to be comforted,

she tasted no food, and ere many days had passed was quite dead.

Messengers were despatched who brought back the unhappy Hiku, author of

all this sorrow. Bitterly he wept over the corpse of his beloved, but it

was now too late; the spirit had departed to the nether world, ruled

over by Milu. And now, stung by the reproaches of her kindred and

friends for his desertion, and urged on by his real love for the fair

one, he resolved to attempt the perilous descent into the nether world

and, if possible, to bring her spirit back.

With the assistance of her friends, he

collected from the mountain slope a great quantity of the kowali, or

convolvulus vine. He also prepared a hollow cocoanut shell, splitting it

into two closely fitting parts. Then anointing himself with a mixture of

rancid cocoanut and kukui oil, which gave him a very strong corpse-like

odor, he started with his companions in the well-loaded canoes for a

point in the sea where the sky comes down to meet the water.

Arrived at the spot, he directed his

comrades to lower him into the abyss called by the Hawaiians the Lua o

Milu. Taking with him his cocoanut-shell and seating himself astride of

the cross-stick of the swing, or kowali, he was quickly lowered down by

the long rope of kowali vines held by his friends in the canoe above.

Soon he entered the great cavern where the

shades of the departed were gathered together. As he came among them,

their curiosity was aroused to learn who he was. And he heard many

remarks, such as “Whew! what an odor this corpse emits!” “He must have

been long dead.” He had rather overdone the matter of the rancid oil.

Even Milu himself, as he sat on the bank watching the crowd, was

completely deceived by the stratagem, for otherwise he never would have

permitted this bold descent of a living man into his gloomy abode.

The Hawaiian swing, it should be remarked,

unlike ours, has but one rope supporting the cross-stick on which the

person is seated. Hiku and his swing attracted considerable attention

from the lookers-on. One shade in particular watched him most intently;

it was his sweetheart, Kawelu. A mutual recognition took place, and with

the permission of Milu she darted up to him and swung with him on the

kowali. But even she had to avert her face on account of his corpse-like

odor. As they were enjoying together this favorite Hawaiian pastime of

lele kowali, by a preconcerted signal the friends above were informed of

the success of his ruse and were now rapidly drawing them up. At first

she was too much absorbed in the sport to notice this. When at length

her attention was aroused by seeing the great distance of those beneath

her, like a butterfly she was about to flit away, when the crafty Hiku,

who was ever on the alert, clapped the cocoanut-shells together,

imprisoning her within them, and was then quickly drawn up to the canoes

above.

With their precious burden, they returned to

the shores of Holualoa, where Hiku landed and at once repaired to the

house where still lay the body of his beloved. Kneeling by its side, he

made a hole in the great toe of the left foot, into which with great

difficulty he forced the reluctant spirit, and in spite of its desperate

struggles he tied up the wound so that it could not escape from the

cold, clammy flesh in which it was now imprisoned. Then he began to

lomilomi, or rub and chafe the foot, working the spirit further and

further up the limb.

Gradually, as the heart was reached, the

blood began once more to flow through the body, the chest began gently

to heave with the breath of life, and soon the spirit gazed out through

the eyes. Kawelu was now restored to consciousness, and seeing her

beloved Hiku bending tenderly over her, she opened her lips and said:

“How could you be so cruel as to leave me?”

All remembrance of the Lua o Milu and of her

meeting him there had disappeared, and she took up the thread of

consciousness just where she had left it a few days before at death.

Great joy filled the hearts of the people of Holualoa as they welcomed

back to their midst the fair Kawelu and the hero, Hiku, from whom she

was no more to be separated.

Location of the Lua o Milu

In the myth of Hiku and Kawelu, the

entrance to the Lua o Milu is placed out to sea opposite Holualoa

and a few miles south of Kailua. But the more usual account of the

natives is, that it was situated at the mouth of the great valley of

Waipio, in a place called Keoni, where the sands have long since

covered up and concealed from view this passage from the upper to

the nether world.

Every year, so it is told, the

procession of ghosts called by the natives Oio, marches in solemn

state down the Mahiki road, and at this point enters the Lua o Milu.

A man, recently living in Waimea, of the best reputation for

veracity, stated that about thirty or more years ago, he actually

saw this ghostly company. He was walking up this road in the

evening, when he saw at a distance the Oio appear, and knowing that

should they encounter him his death would be inevitable, he

discreetly hid himself behind a tree and, trembling with fear, gazed

in silence at the dread spectacle. There was Kamehameha, the

conqueror, with all his chiefs and warriors in military array,

thousands of heroes who had won renown in the olden time. Though all

were silent as the grave, they kept perfect step as they marched

along, and passing through the woods down to Waipio, disappeared

from his view.

In connection with the foregoing,

Professor W. D. Alexander kindly contributes the following:

“The valley of Waipio is a place

frequently celebrated in the songs and traditions of Hawaii, as

having been the abode of Akea and Milu, the first kings of the

island....

“Some said that the souls of the

departed went to the Po (place of night), and were annihilated or

eaten by the gods there. Others said that some went to the regions

of Akea and Milu. Akea (Wakea), they said, was the first king of

Hawaii. At the expiration of his reign, which terminated with his

life at Waipio, where we then were, he descended to a region far

below, called Kapapahanaumoku (the island bearing rock or stratum),

and founded a kingdom there. Milu, who was his successor, and

reigned in Hamakua, descended, when he died, to Akea and shared the

government of the place with him. Their land is a place of darkness;

their food lizards and butterflies. There are several streams of

water, of which they drink, and some said that there were large

kahilis and wide-spreading kou trees, beneath which they reclined.”1

“They had some very indistinct notion of

a future state of happiness and of misery. They said that, after

death, the ghost went first to the region of Wakea, the name of

their first reputed progenitor, and if it had observed the religious

rites and ceremonies, was entertained and allowed to remain there.

That was a place of houses, comforts, and pleasures. If the soul had

failed to be religious, it found no one there to entertain it, and

was forced to take a desperate leap into a place of misery below,

called Milu.

“There were several precipices, from the

verge of which the unhappy ghosts were supposed to take the leap

into the region of woe; three in particular, one at the northern

extremity of Hawaii, one at the western termination of Maui, and the

third at the northern point of Oahu.”

Near the northwest point of Oahu is a

rock called Leina Kauhane, where the souls of the dead descended

into Hades. In New Zealand the same term, “Reinga” (the leaping

place), is applied to the North Cape. The Marquesans have a similar

belief in regard to the northermost island of their group, and apply

the same term, “Reinga,” to their Avernus.

Back to Contents

Lonopuha; Or, Origin

of the Art of Healing in Hawaii,

Translated by Thos. G. Thrum

During the time that Milu was residing at

Waipio, Hawaii, the year of which is unknown, there came to these shores

a number of people, with their wives, from that vague foreign land,

Kahiki. But they were all of godly kind (ano akua nae), it is said, and

drew attention as they journeyed from place to place. They arrived first

at Niihau, and from there they travelled through all the islands. At

Hawaii they landed at the south side, thence to Puna, Hilo, and settled

at Kukuihaele, Hamakua, just above Waipio.

On every island they visited there appeared

various diseases, and many deaths resulted, so that it was said this was

their doings, among the chiefs and people. The diseases that followed in

their train were chills, fevers, headache, pani, and so on.

These are the names of some of these people:

Kaalaenuiahina, Kahuilaokalani, Kaneikaulanaula, besides others. They

brought death, but one Kamakanuiahailono followed after them with

healing powers. This was perhaps the origin of sickness and the art of

healing with medicines in Hawaii.

As has been said, diseases settled on the

different islands like an epidemic, and the practice of medicine ensued,

for Kamakanuiahailono followed them in their journeyings. He arrived at

Kau, stopping at Kiolakaa, on the west side of Waiohinu, where a great

multitude of people were residing, and Lono was their chief. The

stranger sat on a certain hill, where many of the people visited him,

for the reason that he was a newcomer, a custom that is continued to

this day. While there he noticed the redness of skin of a certain one of

them, and remarked, “Oh, the redness of skin of that man!”

The people replied, “Oh, that is Lono, the

chief of this land, and he is a farmer.”

He again spoke, asserting that his sickness

was very great; for through the redness of the skin he knew him to be a

sick man.

They again replied that he was a healthy

man, “but you consider him very sick.” He then left the residents and

set out on his journey.

Some of those who heard his remarks ran and

told the chief the strange words, “that he was a very sick man.” On

hearing this, Lono raised up his oo (digger) and said, “Here I am,

without any sign of disease, and yet I am sick.” And as he brought down

his oo with considerable force, it struck his foot and pierced it

through, causing the blood to flow freely, so that he fell and fainted

away. At this, one of the men seized a pig and ran after the stranger,

who, hearing the pig squealing, looked behind him and saw the man

running with it; and as he neared him he dropped it before him, and told

him of Lono’s misfortune, Kamakanuiahailono then returned, gathering on

the way the young popolo seeds and its tender leaves in his garment (kihei).

When he arrived at the place where the wounded man was lying he asked

for some salt, which he took and pounded together with the popolo and

placed it with a cocoanut covering on the wound. From then till night

the flowing of the blood ceased. After two or three weeks had elapsed he

again took his departure.

While he was leisurely journeying, some one

breathing heavily approached him in the rear, and, turning around, there

was the chief, and he asked him: “What is it, Lono, and where are you

going?”

Lono replied, “You healed me; therefore, as

soon as you had departed I immediately consulted with my successors, and

have resigned my offices to them, so that they will have control over

all. As for myself, I followed after you, that you might teach me the

art of healing.”

The kahuna lapaau (medical priest) then

said, “Open your mouth.” When Lono opened his mouth, the kahuna spat

into it,1 by which he would become proficient in the calling he had

chosen, and in which he eventually became, in fact, very skilful.

As they travelled, he instructed Lono (on

account of the accident to his foot he was called Lonopuha) in the

various diseases, and the different medicines for the proper treatment

of each. They journeyed through Kau, Puna, and Hilo, thence onward to

Hamakua as far as Kukuihaele. Prior to their arrival there,

Kamakanuiahailono said to Lonopuha, “It is better that we reside apart,

lest your healing practice do not succeed; but you settle elsewhere, so

as to gain recognition from your own skill.”

For this reason, Lonopuha went on farther

and located in Waimanu, and there practised the art of healing. On

account of his labors here, he became famous as a skilful healer, which

fame Kamakanuiahailono and others heard of at Kukuihaele; but he never

revealed to Kaalaenuiahina ma (company) of his teaching of Lonopuha,

through which he became celebrated. It so happened that Kaalaenuiahina

ma were seeking an occasion to cause Milu’s death, and he was becoming

sickly through their evil efforts.

When Milu heard of the fame of Lonopuha as a

skilful healer, because of those who were afflicted with disease and

would have died but for his treatment, he sent his messenger after him.

On arriving at Milu’s house, Lonopuha examined and felt of him, and then

said, “You will have no sickness, provided you be obedient to my

teachings.” He then exercised his art, and under his medical treatment

Milu recovered.

Lonopuha then said to him: “I have treated

you, and you are well of the internal ailments you suffered under, and

only that from without remains. Now, you must build a house of leaves

and dwell therein in quietness for a few weeks, to recuperate.” These

houses are called pipipi, such being the place to which invalids are

moved for convalescent treatment unless something unforeseen should

occur.

Upon Milu’s removal thereto, Lonopuha

advised him as follows: “O King! you are to dwell in this house

according to the length of time directed, in perfect quietness; and

should the excitement of sports with attendant loud cheering prevail

here, I warn you against these as omens of evil for your death; and I

advise you not to loosen the ti leaves of your house to peep out to see

the cause, for on the very day you do so, that day you will perish.”

Some two weeks had scarcely passed since the

King had been confined in accordance with the kahuna’s instructions,

when noises from various directions in proximity to the King’s dwelling

were heard, but he regarded the advice of the priest all that day. The

cause of the commotion was the appearance of two birds playing in the

air, which so excited the people that they kept cheering them all that

day.

Three weeks had almost passed when loud

cheering was again heard in Waipio, caused by a large bird decorated

with very beautiful feathers, which flew out from the clouds and soared

proudly over the palis (precipices) of Koaekea and Kaholokuaiwa, and

poised gracefully over the people; therefore, they cheered as they

pursued it here and there. Milu was much worried thereby, and became so

impatient that he could no longer regard the priest’s caution; so he

lifted some of the ti leaves of his house to look out at the bird, when

instantly it made a thrust at him, striking him under the armpit,

whereby his life was taken and he was dead (lilo ai kona ola a make iho

la).

The priest saw the bird flying with the

liver of Milu; therefore, he followed after it. When it saw that it was

pursued, it immediately entered into a sunken rock just above the base

of the precipice of Koaekea. As he reached the place, the blood was

spattered around where the bird had entered. Taking a piece of garment (pahoola),

he soaked it with the blood and returned and placed it in the opening in

the body of the dead King and poured healing medicine on the wound,

whereby Milu recovered. And the place where the bird entered with Milu’s

liver has ever since been called Keakeomilu (the liver of Milu).

A long while afterward, when this death of

the King was as nothing (i mea ole), and he recovered as formerly, the

priest refrained not from warning him, saying: “You have escaped from

this death; there remains for you one other.”

After Milu became convalescent from his

recent serious experience, a few months perhaps had elapsed, when the

surf at Waipio became very high and was breaking heavily on the beach.

This naturally caused much commotion and excitement among the people, as

the numerous surf-riders, participating in the sport, would land upon

the beach on their surf-boards. Continuous cheering prevailed, and the

hilarity rendered Milu so impatient at the restraint put upon him by the

priest that he forsook his wise counsel and joined in the exhilarating

sport.

Seizing a surf-board he swam out some

distance to the selected spot for suitable surfs. Here he let the first

and second combers pass him; but watching his opportunity he started

with the momentum of the heavier third comber, catching the crest just

right. Quartering on the rear of his board, he rode in with majestic

swiftness, and landed nicely on the beach amid the cheers and shouts of

the people. He then repeated the venture and was riding in as

successfully, when, in a moment of careless abandon, at the place where

the surfs finish as they break on the beach, he was thrust under and

suddenly disappeared, while the surf-board flew from under and was

thrown violently upon the shore. The people in amazement beheld the

event, and wildly exclaimed: “Alas! Milu is dead! Milu is dead!” With

sad wonderment they searched and watched in vain for his body. Thus was

seen the result of repeated disobedience. Back

to Contents

A Visit to the

Spirit

Land; Or, The Strange Experience of a

Woman in Kona, Hawaii,

Mrs. E. N. Haley

Kalima had been sick for many weeks, and at

last died. Her friends gathered around her with loud cries of grief, and

with many expressions of affection and sorrow at their loss they

prepared her body for its burial.

The grave was dug, and when everything was

ready for the last rites and sad act, husband and friends came to take a

final look at the rigid form and ashen face before it was laid away

forever in the ground. The old mother sat on the mat-covered ground

beside her child, brushing away the intrusive flies with a piece of

cocoanut-leaf, and wiping away the tears that slowly rolled down her

cheeks. Now and then she would break into a low, heart-rending wail, and

tell in a sob-choked, broken voice, how good this her child had always

been to her, how her husband loved her, and how her children would never

have any one to take her place. “Oh, why,” she cried, “did the gods

leave me? I am old and heavy with years; my back is bent and my eyes are

getting dark. I cannot work, and am too old and weak to enjoy fishing in

the sea, or dancing and feasting under the trees. But this my child

loved all these things, and was so happy. Why is she taken and I, so

useless, left?” And again that mournful, sob-choked wail broke on the

still air, and was borne out to the friends gathered under the trees

before the door, and was taken up and repeated until the hardest heart

would have softened and melted at the sound. As they sat around on the

mats looking at their dead and listening to the old mother, suddenly

Kalima moved, took a long breath, and opened her eyes. They were

frightened at the miracle, but so happy to have her back again among

them.

The old mother raised her hands and eyes to

heaven and, with rapt faith on her brown, wrinkled face, exclaimed: “The

gods have let her come back! How they must love her!”

Mother, husband, and friends gathered around

and rubbed her hands and feet, and did what they could for her comfort.

In a few minutes she revived enough to say, “I have something strange to

tell you.”

Several days passed before she was strong

enough to say more; then calling her relatives and friends about her,

she told them the following weird and strange story:

“I died, as you know. I seemed to leave my

body and stand beside it, looking down on what was me. The me that was

standing there looked like the form I was looking at, only, I was alive

and the other was dead. I gazed at my body for a few minutes, then

turned and walked away. I left the house and village, and walked on and

on to the next village, and there I found crowds of people,—Oh, so many

people! The place which I knew as a small village of a few houses was a

very large place, with hundreds of houses and thousands of men, women,

and children. Some of them I knew and they spoke to me,—although that

seemed strange, for I knew they were dead,—but nearly all were

strangers. They were all so happy! They seemed not to have a care;

nothing to trouble them. Joy was in every face, and happy laughter and

bright, loving words were on every tongue.

“I left that village and walked on to the

next. I was not tired, for it seemed no trouble to walk. It was the same

there; thousands of people, and every one so joyous and happy. Some of

these I knew. I spoke to a few people, then went on again. I seemed to

be on my way to the volcano,—to Pele’s pit,—and could not stop, much as

I wanted to do so.

“All along the road were houses and people,

where I had never known any one to live. Every bit of good ground had

many houses, and many, many happy people on it. I felt so full of joy,

too, that my heart sang within me, and I was glad to be dead.

“In time I came to South Point, and there,

too, was a great crowd of people. The barren point was a great village,

I was greeted with happy alohas, then passed on. All through Kau it was

the same, and I felt happier every minute. At last I reached the

volcano. There were some people there, but not so many as at other

places. They, too, were happy like [61]the others, but they said, ‘You

must go back to your body. You are not to die yet.’

“I did not want to go back. I begged and

prayed to be allowed to stay with them, but they said, ‘No, you must go

back; and if you do not go willingly, we will make you go.’

“I cried and tried to stay, but they drove

me back, even beating me when I stopped and would not go on. So I was

driven over the road I had come, back through all those happy people.

They were still joyous and happy, but when they saw that I was not

allowed to stay, they turned on me and helped drive me, too.

“Over the sixty miles I went, weeping,

followed by those cruel people, till I reached my home and stood by my

body again. I looked at it and hated it. Was that my body? What a

horrid, loathsome thing it was to me now, since I had seen so many

beautiful, happy creatures! Must I go and live in that thing again? No,

I would not go into it; I rebelled and cried for mercy.

“‘You must go into it; we will make you!’

said my tormentors. They took me and pushed me head foremost into the

big toe.

“I struggled and fought, but could not help

myself. They pushed and beat me again, when I tried for the last time to

escape. When I passed the waist, I seemed to know it was of no use to

struggle any more, so went the rest of the way myself. Then my body came

to life again, and I opened my eyes.

“But I wish I could have stayed with those

happy people. It was cruel to make me come back. My other body was so

beautiful, and I was so happy, so happy!” Back

to Contents

Kapeepeekauila;

Or, The Rocks of Kana, Rev. A. O. Forbes

On the

northern side of the island of Molokai, commencing at the eastern end

and stretching along a distance of about twenty miles, the coast is a

sheer precipice of black rock varying in height from eight hundred to

two thousand feet. The only interruptions to the continuity of this vast

sea wall are formed by the four romantic valleys of Pelekunu, Puaahaunui,

Wailau, and Waikolu. Between the valleys of Pelekunu and Waikolu, juts

out the bold, sharp headland of Haupu, forming the dividing ridge

between them, and reminding one somewhat of an axe-head turned edge

upward. Directly in a line with this headland, thirty or forty rods out

in the ocean, arise abruptly from the deep blue waters the rocks of

Haupu, three or four sharp, needle-like points of rock varying from

twenty to one hundred feet in height. This is the spot associated with

the legend of Kapeepeekauila, and these rocks stand like grim sentinels

on duty at the eastern limit of what is now known as the settlement of

Kalawao. The legend runs as follows:

Keahole was the father, Hiiaka-noholae was

the mother, and Kapeepeekauila was the son. This Kapeepeekauila was a

hairy man, and dwelt on the ridge of Haupu.

Once on a time Hakalanileo and his wife

Hina, the mother of Kana, came and dwelt in the valley of Pelekunu, on

the eastern side of the ridge of Haupu.

Kapeepeekauila, hearing of the arrival of

Hina, the beautiful daughter of Kalahiki, sent his children to fetch

her. They went and said to Hina, “Our royal father desires you as his

wife, and we have come for you.”

“Desires me for what?” said she.

“Desires you for a wife,” said they.

This announcement pleased the beautiful

daughter of Kalahiki, and she replied, “Return to your royal father and

tell him he shall be the husband and I will be the wife.”

When this message was delivered to

Kapeepeekauila, he immediately sent a messenger to the other side of the

island to summon all the people from Keonekuina to Kalamaula; for we

have already seen that he was a hairy man, and it was necessary that

this blemish should be removed. Accordingly, when the people had all

arrived, Kapeepeekauila laid himself down and they fell to work until

the hairs were all plucked out. He then took Hina to wife, and they two

dwelt together on the top of Haupu.

Poor Hakalanileo, the husband of Hina,

mourned the loss of his companion of the long nights of winter and the

shower-sprinkled nights of summer. Neither could he regain possession of

her, for the ridge of Haupu grew till it reached the heavens. He mourned

and rolled himself in the dust in agony, and crossed his hands behind

his back. He went from place to place in search of some powerful person

who should be able to restore to him his wife. In his wanderings, the

first person to whom he applied was Kamalalawalu, celebrated for

strength and courage. This man, seeing his doleful plight, asked, “Why

these tears, O my father?”

Hakalanileo replied, “Thy mother is lost.”

“Lost to whom?”

“Lost to Kapeepee.”

“What Kapeepee?”

“Kapeepee-kauila.”

“What Kauila?”

“Kauila, the dauntless, of Haupu.”

“Then, O father, thou wilt not recover thy

wife. Our stick may strike; it will but hit the dust at his feet. His

stick, when it strikes back, will hit the head. Behold, measureless is

the height of Haupu.”

Now, this Kamalalawalu was celebrated for

his strength in throwing stones. Of himself, one side was stone, and the

other flesh. As a test he seized a large stone and threw it upwards. It

rose till it hit the sky and then fell back to earth again. As it came

down, he turned his stony side toward it, and the collision made his

side rattle. Hakalanileo looked on and sadly said, “Not strong enough.”

On he went, beating his breast in his grief,

till he came to the celebrated Niuloihiki. Question and answer passed

between them, as in the former case, but Niuloihiki replied, “It is

hopeless; behold, measureless is the height of Haupu.”

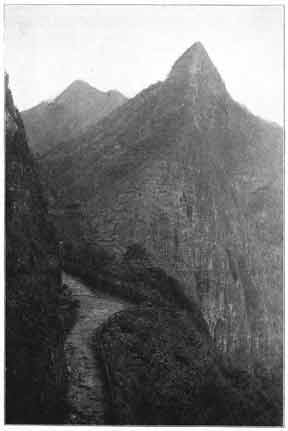

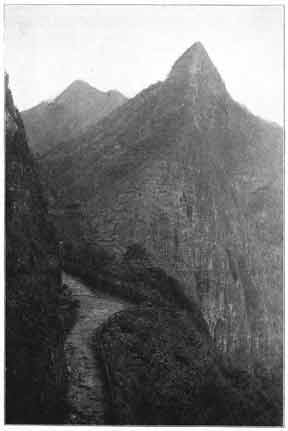

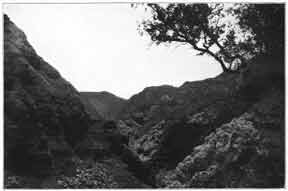

View

in

Wainiha

Valley,

Kauai.

Again he prosecuted his search till he met

the third man of fame, whose name was Kaulu. Question and answer passed,

as before, and Kaulu, to show his strength, seized a river and held it

fast in its course. But Hakalanileo mournfully said, “Not strong

enough.”

Pursuing his way with streaming eyes, he

came to the fourth hero, Lonokaeho by name. As in the former cases, so

in this, he received no satisfaction. These four were all he knew of who

were foremost in prowess, and all four had failed him. It was the end,

and he turned sadly toward the mountain forest, to return to his home.

Meantime, the rumor had reached the ears of

Niheu, surnamed “the Rogue.” Some one told him a father had passed along

searching for some one able to recover him his wife.

“Where is this father of mine?” inquired

Niheu.