Kapa

by Betty Fullard-Leo

Kapa making is an art that once spanned the

Pacific, but it reached perfection in Polynesia. The artistic beauty of

the cloth made of pounded bark impressed Captain James Cook in 1778.

"One would suppose," he wrote in his journal, "that they (Hawaiians) had

borrowed their patterns from some mercer's shop in which the most

elegant productions of China and Europe are collected, besides (having)

some patterns of their own...The regularity of the figures and stripes

is truly surprising." Kapa making is an art that once spanned the

Pacific, but it reached perfection in Polynesia. The artistic beauty of

the cloth made of pounded bark impressed Captain James Cook in 1778.

"One would suppose," he wrote in his journal, "that they (Hawaiians) had

borrowed their patterns from some mercer's shop in which the most

elegant productions of China and Europe are collected, besides (having)

some patterns of their own...The regularity of the figures and stripes

is truly surprising."In old Hawai'i, kapa was used in nearly every aspect of life. It swaddled newborns and was fashioned into malo for the men and pa'u skirts for women, as well as kihei (capes) worn by both. Several layers of kapa stitched together made kapa moe, sleeping blankets, while small plain strips might be wrapped around an individual's arms and legs for decoration, and orange strips of kapa were used to adorn the hair. Kapa played a part in religious practices, as well. Tall towers called 'anu'u, which stood atop heiau and were thought to house the gods when they communicated with the kahuna, were draped with sheets of white kapa. Idols were also decorated with kapa to show that the gods lived inside the wooden figures.  When Reverend William Ellis described women of Kailua-Kona making kapa,

he wrote in his "Narrative of a Tour Through Hawai'i" published in 1826,

"The fabrication of it shows both invention and industry; and whether we

consider its different textures, its varied and regular patterns, its

beautiful colours, so admirably preserved by means of the varnish, we

are at once convinced that the people who manufacture it are neither

deficient in taste, nor incapable of receiving the improvements of

civilized society." When Reverend William Ellis described women of Kailua-Kona making kapa,

he wrote in his "Narrative of a Tour Through Hawai'i" published in 1826,

"The fabrication of it shows both invention and industry; and whether we

consider its different textures, its varied and regular patterns, its

beautiful colours, so admirably preserved by means of the varnish, we

are at once convinced that the people who manufacture it are neither

deficient in taste, nor incapable of receiving the improvements of

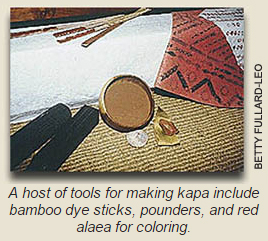

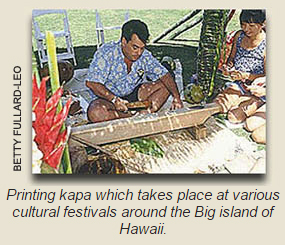

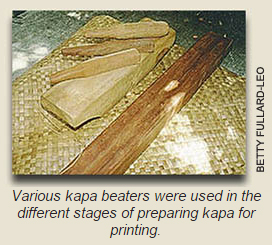

civilized society."One of those "improvements of civilized society" was the introduction of woven cloth, which became so available that kapa-making disappeared within a century after Cook sailed through the islands. It wasn't until the 1970s, that a resurgence of interest and pride in the Hawaiian culture caused artisans like the Big Island's Kanae Keawe and Puanani Van Dorpe to research the old techniques and attempt to revive the art. Keawe says, "I was self-taught. There were no kupuna living who could tell us the correct way to make kapa, so I did a lot of research at Bishop Museum. I read Peter Buck's books and others on Hawaiian arts and crafts, studied Fijian kapa making at Polynesian Cultural Center. I'm a woodcarver originally, so I was able to recreate the tools." It quickly became apparent to Keawe and Van Dorpe that the process of making kapa is long and arduous. In old Hawai'i, Reverend Ellis described the cultivation of wauti (mulberry) trees neatly planted two feet apart and allowed to grow perhaps two years before the sticks were harvested for their bark. Mamaki and other types of bark were used as well, but wauti was most popular. Ellis wrote about the process, "...we perceived Keoua, the governor's wife, and her female attendants with about forty other women, under the pleasant shade of a beautiful clump of cordia or kou trees, employed in stripping the bark from bundles of wauti sticks, for the purpose of making cloth with it. The sticks were generally from six to ten feet long, and about an inch in diameter at the thickest end. They first cut the bark the whole length of the stick with a sharp serrated shell, and having carefully peeled it off, rolled it into small coils, the inner bark being outside. In this state it is left some time, to make it flat and smooth." After several days, the strips of bark were unrolled, laid flat, and the outer bark was scraped off with a large shell. The remaining inner bark was rolled up again and soaked in sea water for a week to soften it and remove any resin. In the first of two beating stages, the softened strips were laid across a stone anvil and beaten with a round beater (hohoa) turning them into long thin strips called mo'omo'o. Next came bleaching in the sun and another soaking to soften the mo'omo'o for the second stage of beating on a wooden anvil (kua kuku) with a square beater (ie kuku). The thin mo'omo'o were overlapped and beaten together to obtain the size desired without any visible seams.  Kapa beaters were four-sided affairs, with the coarsest grooves on one

side used first in breaking down the bast, or wet bark. The beating

continued using two sides with finer grooves, until finally, finishing

touches were accomplished with the remaining smooth side of the beater.

Before the kapa was laid out to dry in the sun, a kapa maker might

emboss her bark cloth with her own special design which would show

through on the finished product much like a watermark on fine paper. Kapa beaters were four-sided affairs, with the coarsest grooves on one

side used first in breaking down the bast, or wet bark. The beating

continued using two sides with finer grooves, until finally, finishing

touches were accomplished with the remaining smooth side of the beater.

Before the kapa was laid out to dry in the sun, a kapa maker might

emboss her bark cloth with her own special design which would show

through on the finished product much like a watermark on fine paper.Nineteenth-century historian Samuel Kamakau estimated a woman could make one or two lengths of kapa a day, which was bleached in the sun, then exposed to the night dew and bleached repeatedly to give the cloth a sheen that was reasonably moisture resistant. Fine kapa was dyed with a variety of patterns according to the maker's whim and creative talent. Ellis described a pa'u cloth as: "generally four yards long and about a yard wide, very thick, beautifully painted with brilliant red, yellow, black colours, and covered over with a fine gum and resinous varnish, which not only preserves the colours, but renders the cloth impervious and durable." Red dyes were made from the bark of the noni and kolea trees and the leaves of kou and amaumau. Yellow came from the roots of the olena and noni and the bark and roots of holei. Berries-akala (a variety of raspberry) and ukiuki-yielded pink and pale blue. Lavender and purple were obtained from sea urchin ink, while green came from the leaves of mao. Red and yellow ochers from minerals pulverized with a mortar and pestle were mixed with kukui oil for another lasting dye. Sometimes kapa was scented with coconut oil cooked with stems and leaves of fragrant laua'e fern, or simply transferred to the cloth by placing aromatic maile vine or sandalwood bark between the sheets. In addition to painting kapa freehand with a hala brush dipped in dye, the artisans, reported Ellis, "cut the pattern they intend to stamp on their cloth on the inner side of a narrow piece of bamboo, spread their cloth before them on a board, and having their colours properly mixed in a calabash by their side, dip the point of the bamboo, which they hold in their right hand, into the paint and strike it against the edge of the calabash, place it on the right or left side of the cloth, and press it down with the fingers of the left hand. The pattern is continued until the cloth is marked quite across, when it is moved on the board, and the same repeated till it is finished." The finished product was so treasured it might be given as a gift to an ali'i or saved for a bride's dowry. By the mid 1970s, Kanae Keawe had learned enough to pass the techniques of kapa making on through demonstrations and workshops sponsored by the Honolulu Academy of Arts, Temari Center for Asian and Pacific Arts, and various Hawaiian civic clubs. Students of his, like Happy Tamanaha, a Honolulu art teacher, have passed the knowledge to others. However, Keawe estimates it might take 500 hours to produce a piece of kapa large enough to cover a bed; the cost of such a piece would be prohibitive. Another skilled kapa artisan now living on the Big Island, Puanani Van Dorpe has made wall hangings for the Sheraton Maui Hotel (which was remodeled last year), as well as a 16-foot pa'u that is displayed at the Hilton Hawaiian Village Tapa Tower on O'ahu. More than 20 years ago, Van Dorpe grew familiar with Fijian kapa when she lived in Fiji for a time. Back in Hawai'i, while volunteering at the Bishop Museum, she was astounded to see how much finer the tissue-thin Hawaiian kapa was. "The Fijians just beat their bark for two days and they have a sheet of kapa; there's no fermentation period," she explains. She acquired a collection of 18th and 19th-Century museum-quality kapa which she inspected through a microscope, then worked to duplicate the exact fiber patterns in her 20th-Century recreations. "I realized I had to have help," says Van Dorpe, "so I began to rely on my 'aumakuas. Two sisters are the goddesses of kapa-Lauhuki and La'ahana. One is for beating, the other for the decorating process." Van Dorpe has also passed on her knowledge on to her daughter, as well as through workshops with Keawe at Temari Center. Besides Van Dorpe's modern pieces at the Sheraton Maui, which symbolically represent events in Maui history on 3-foot by 7-foot panels, beautiful kapa pieces can be viewed at Four Seasons Resort Hawai'i at Hualalai on the Big Island. Displayed near the ballroom are two kapa moe that measure 6 1/2 by 7 1/2 feet, originally used as bedding about 1850, while a very rare kapa robe was worn by an early missionary in 1823. The tools-seashells for scraping bark, an anvil, kapa beaters, bamboo dyeing sticks, and 'alaea (red earth for dyeing) to create kapa can be viewed in the resort's Cultural Learning Center. Other items are on display in the Lyman Mission House and Museum in Hilo. Bishop Museum and a few British museums have the finest samples. Today, kapa, which was used to swaddle the ali'i of old at birth, as well as to wrap them for their journey after death, is a rare and treasured artifact, but it is no longer a lost art. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |