Maui: The Demi-God

|

Maui is a demi-god whose name should probably be pronounced Ma-u-i-, i. e., Ma-oo-e. The meaning of the words is by no means clear. It may mean "to live, " "to subsist." It may refer to beauty and strength, or it may have the idea of "the left hand" or "turning aside." The word is recognized as belonging to remote Polynesian antiquity. MacDonald, a writer of the New Hebrides Islands gives the derivation of the name Maui primarily from the Arabic word, "Mohyi," which means "causing to live" or "life,“ applied sometimes to the gods and sometimes to chiefs as "preservers and sustainers" of their followers.

The Maui story probably contains a larger number of unique and ancient myths than that of any other legendary character in the mythology of any nation. There are three centers for these legends, New Zealand in the south, Hawaii in the north, and the Tahitian group including the Hervey Islands in the east. In each of these groups of islands, separated by thousands of miles, there are the same legends, told in almost the same way, and with very little variation in names. The intermediate groups of islands of even as great importance as Tonga, Fiji or Samoa, possess the same legends in more or less of a fragmentary condition, as if the three centers had been settled first when the Polynesians were driven away from the Asiatic coasts by their enemies, the Malays. From these centers voyagers sailing away in search of adventures would carry fragments rather than complete legends. This is exactly what has been done and there are as a result a large number of hints of wonderful deeds. The really long legends as told about the demi-god Ma-u-i and his mother Hina number about twenty.

It is remarkable that these legends have kept their individuality. The Polynesians are not a very clannish people. For some centuries they have not been in the habit of frequently visiting each other. They have had no written language, and picture writing of any kind is exceedingly rare throughout Polynesian and yet in physical traits, national customs, domestic habits, and language, as well as in traditions and myths, the different inhabitants of the islands of Polynesia are as near of kin as the cousins of the United States and Great Britain. The Maui legends form one of the strongest links in the mythological chain of evidence which binds the scattered inhabitants of the Pacific into one nation. An incomplete list aids in making clear the fact that groups of islands hundreds and even thousands of miles apart have been peopled centuries past by the same organic race. Either complete or fragmentary Maui legends are found in the single islands and island groups of Aneityum, Bowditch or Fakaofa, Efate, Fiji, Fotuna, Gilbert, Hawaii, Hervey, Huahine, Mangaia, Manihiki, Marquesas, Marshall, Nauru, New Hebrides, New Zealand, Samoa, Savage, Tahiti or Society, Tauna, Tokelau and Tonga.

S. Percv Smith of New Zealand in his book Hawaiki mentions a legend according to which Mani made a voyage after overcoming a sea monster, visiting the Tongas, the Tahitian group, Vai-i or Hawaii, and the Paumotu Islands. Then Maui went on to U-peru, which Mr. Smith says "may be Peru." It was said that Maui named some of the islands of the Hawaiian group, calling the island Maui "Maui-ui in remembrance of his efforts in lifting up the heavens," Hawaii was named Vai-i, and Lanai was called Ngangai as if Maui had found the three most southerly islands of the group. The Maui legends possess remarkable antiquity. Of course, it is impossible to give any definite historical date, but there can scarcely be any question of their origin among the ancestors of the Polynesians before they scattered over the Pacific ocean. They belong to the prehistoric Polynesians. The New Zealanders claim Maui as an ancestor of their most ancient tribes and sometimes class him among the most ancient of their gods, calling him "creator of land" and "creator of man." Tregear, in a paper before the New Zealand Institute, said that Maui was sometimes thought to be "the sun himself," "the solar fire," "the sun god," while his mother Hina was called ' ' the moon goddess. The noted greenstone god of the Maoris of New Zealand, Potiki, may well be considered a representation of Maui-Tiki-Tiki, who was sometimes called Maui-po-tiki. It is worth while in this place to quote Sir James Carroll, of New Zealand, who was for a long time the Government Minister having charge of native affairs. His high caste native blood and great ability gave him a place in the highest order of chiefs among the Maoris. He says that the greenstone charm Potiki (often called Tiki) is the symbol of the unborn child according to the thought of the chiefs best acquainted with Maori folk-lore ; and Maui was a demi-god developing life after being thrown away as a foetus prematurely born, thus representing the first formed child after whom the Potiki was named.

Whether these legends came to the people in their sojourn in India before they migrated to the Straits of Sunda is not certain; but it may well be assumed that these stories had taken firm root in the memories of the priests who transmitted the most important traditions from generation to generation, and that this must have been done before they were driven away from the Asiatic coasts by the Malays. Several hints of Hindoo connection are found in the Maui legends. The Polynesians not only ascribed human attributes to all animal life with which they were acquainted, but also carried the idea of an alligator or dragon with them, wherever they went, as in the mo-o of the story Tuna-roa. The Polynesians also had the idea of a double soul inhabiting the body. This is carried out in the ghost legends more fully than in the Maui stories, “and yet the spirit separate from the spirit which never forsakes man" according to Polynesian ideas, was a part of the Maui birth legends. This spirit, which can be separated or charmed away from the body by incantations was called the "hau." When Maui's father performed the religious ceremonies over him which would protect him and cause him to be successful, he forgot a part of his incantation to the "hau, "therefore Maui lost his protection from death when he sought immortality for himself and all mankind.

How much these things aid in proving a Hindoo or rather Indian origin for the Polynesians is uncertain, but at least they are of interest along the lines of race origin. The Maui group of legends is pre-eminently peculiar. They are not only different from the myths of other nations, but they are unique in the character of the actions recorded. Maui 's deeds rank in a higher class than most of the mighty efforts of the demi-gods of other nations and races, and are usually of more utility. Hercules accomplished nothing to compare with ”lifting the sky,” "snaring the sun," ''fishing for islands," "finding fire in his grandmother's fingernails," or "learning from birds how to make fire by rubbing dry sticks," or "getting a magic bone" from the jaw of an ancestor who was half dead, that is dead on one side and therefore could well afford to let the bone on that side go for the benefit of a descendant. The Maui legends are full of helpful imaginations, which are distinctly Polynesian.

The phrase "Maui of the Malo" is used among the Hawaiians in connection with the name Maui a Kalana, "Maui the son of Akalana." It may be well to note the origin of the name. It was said that Hina usually sent her retainers to gather sea moss for her, but one morning she went down to the sea by herself. There she found a beautiful red malo, which she wrapped around her as a pa-u or skirt. When she showed it to Akalana, her husband, he spoke of it as a gift of the gods, thinking that it meant the gift of Mana or spiritual power to their child when he should be born. In this way the Hawaiians explain the superior talent and miraculous ability of Maui which placed him above his brothers. These stories were originally printed as magazine articles, chiefly in the Paradise of the Pacific, Honolulu; therefore there are sometimes repetitions which it seemed best to leave, even when reprinted in the present form. Back to Contents

By S. Percy Smith, F.R.G.S., President, Polynesian Society.

MAUI, the demi-god, looms very largely in Polynesian myth, tradition, and folk-lore. Mr. Westervelt does well to call him a demi-god, for god he assuredly was not. He stands on quite a different plane to the gods of the race, and might appropriately be called a "hero," because he embodies the Polynesian idea of a hero a gifted, clever, daring, impudent, rollicking fellow, endowed moreover with that kind of mana which in this connection may be translated supernatural power that enabled him to outdo the feats of ordinary mankind. He also occupies a position in his family of brothers, which always appeals to the Polynesian (indeed, to other races as well) in that he was the youngest of them the Cinderella, the despised and mischievous child who by force of character eventually became the leader of the family. Many and many a Polynesian tale hinges on the rise of the youngest of a family to the place of honor and importance in a tribe.

Maui has several additional names, all expressive of some of his characteristics; such as Maui-potiki (Maui-the-youngest), Maui-tikitiki-a-Taranga (Maui-topknotof Taranga, his mother, the origin of which name Mr. Westervelt has given); Maui-hangarau (Maui-of-themany-schemes), and so on. Each division of the race has its special pet name for the hero, descriptive of the achievement that appeals most to the particular branch that originated the name. As time passed, and the branches of the Polynesian race separated off into the various islands in which they are now found, the deeds of Maui became subject to the well known and world-wide processes of alteration due to local environment and localization, giving rise to variations from the story as learnt (or invented) in the ancient "Father-land" of the people. From like causes the deeds of other heroes are now often accredited to Maui; but these can often be separated out and assigned to their proper places and periods. Notwithstanding this, the general agreement of the series of Maui legends wherever obtained among the Polynesians is somewhat remarkable, as is proved by Mr. Westervelt 's work. This, of course, means that the legends came into being before the dispersion of the people to the islands of the Pacific. And one part but not all of them probably originated during the sojourn of the Polynesians in Indonesia. There has been an overflow of the Maui legends into the islands inhabited by the black, or very dark, Melansians to the west of Polynesia proper; but with such a distortion of narratives and names, that we conclude they are not original with that people they were, in fact, learnt by them from some of the westward migrations of the Polynesians who have, in many instances, settled on some of the outlying islands of Melanesia.

A careful study of the various legends (which has not as yet been undertaken exhaustively), will clearly lead to the inference that some are immensely older than others. When we reflect that traces of the most ancient Maui stories are to be discovered in the literature written and unwritten of Egypt, Babylonia, Scandinavia, India, and also in North America, we are at once faced with the fact of the immense antiquity of the early Maui legends. "We may take as one of the most ancient of these, that relating to Maui's successful efforts to lengthen the day-light. The only reasonable interpretation that can be placed on this is, the dimly remembered period when the people were living in some country where the winter days were very short, and that the lengthened days were secured to the people by migrating towards the temperate or tropical regions of the earth; possibly under the leadership of one named Maui, or, what is more probable, the deeds of this migratory leader may have been in after ages, when the legends surrounding the historical Mam became rife, accredited to him as the national hero. It may be suggested that if the Polynesians are, as some of us suppose, Proto-Aryans who in very ancient times led the advance guard of the Aryan migration from let us say, with Oppert the shores of the Baltic, to south-eastern Asia, then the legends of Maui's deeds in lengthening the days would, in a measure, be accounted for.

Another of the Maui legends is doubtless far more ancient than the period of the historical Maui. Mr. Westervelt describes the death of the hero as arising through his endeavour to secure everlasting life to mankind, in which undertaking he was frustrated and killed by Hine-nui-te-po, the goddess of Hades. The period of this incident is so ancient, that according to the esoteric teaching of the priests and teachers of the Maori Whare-wananga (or college), it occurred not long after the creation of mankind, in that mysterious "Father-land" of the race named Hawaiki. Hinenui-te-po was, according to the above teaching, the second woman created, and was both wife and daughter of Tane, the most celebrated of the Maori gods. On discovering that Tane was her father she was so overcome with shame and horror that she departed for Hades, where she took the name of Hine-nui-te-po, Great-lady-of-Hades, and became the goddess of those realms, where she ever occupies herself in dragging down to death the offspring of mankind. This shows how ancient the legend is, and that it cannot be placed in the period of the historical Maui he who "fished up" so many lands, or in other words, discovered so many islands.

The story of Maui's acquisition of fire for the use of mankind, belongs probably to the ancient division of the series (whilst it might also be modern), if the teaching of the Maori college is considered. In that teaching the fire is stated to be ”Ahi-komau," or volcanic fire. If so, the interpretation of the story may be, that Polynesian mankind first obtained fire from incandescent lava, and the subsequent conflagration of the country Te-ahi-a-Maui may be the frequent accompaniment of volcanic outbursts as often experienced when the vegetation is frequently set ablaze. It is, we submit, undoubtedly the case that there was a family of the name of Maui who flourished according to the best Maori genealogies about 50 generations ago, or, in other words, in the seventh century; a period, which the most reliable traditions seem to indicate as that when a later migration of the Polynesian people (known for convenience as the "Tonga-fiti" branch of the race) were dwelling in Indonesia, and beginning to spread into the borders of the Pacific. And it was here probably the stories of Maui's "fishing up" of lands originated, in the discovery of many new islands by that hero. Or, what is just as likely, many a voyage of discovery by other leaders has been in the process of time accredited to the national hero. The Maori descents from the four Maui brothers are in sufficient accordance to allow of our indicating the seventh century as the period in which they flourished. Their descendants are to be found in most of the islands occupied by the Polynesians, excepting perhaps the western groups of Samoa, Tonga, etc., who do not belong to the “Tonga-fiti" branch.

That the legends of the doings of Maui in Indonesia have been localized in the various islands of the Pacific, is only what might be expected from what we know of similar cases in other parts of the world. It would therefore seem that a distinction must be drawn between the several legends of Maui that some are of untold antiquity, others of comparatively-speaking modern date, and historical.

Mr. "Westervelt has placed students of Polynesian history and traditions under a deep debt of gratitude by collecting from so many sources the various versions as handed down by the Polynesians in their scattered homes all over the Pacific. We are now, for the first time, in a position to deal comprehensively with the subject, and let us hope, with his book before us, we shall be enabled to throw a further ray of light on the history of this most interesting people. Back to Contents

FOUR BROTHERS, each bearing the name of Maui, belong to Hawaiian legend. They accomplished little as a family, except on special occasions when the youngest of the household awakened his brothers by some unexpected trick which drew them into unwonted action. The legends of Hawaii, Tonga, Tahiti, New Zealand and the Hervey group make this youngest Maui ''the discoverer of fire" or "the ensnarer of the sun" or "the fisherman who pulls up islands" or "the man endowed with magic," or "Maui with spirit power." The legends vary somewhat, of course, but not as much as might be expected when the thousands of miles between various groups of islands are taken into consideration.

Maui was one of the Polynesian demi-gods. His parents belonged to the family of supernatural beings. He himself was possessed of supernatural powers and was supposed to make use of all manner of enchantments. In New Zealand antiquity a Maui was said to have assisted other gods in the creation of man. Nevertheless Maui was very human. He lived in thatched houses, had wives and children, and was scolded by the women for not properly supporting his household.

The time of his sojourn among men is very indefinite. In Hawaiian genealogies Maui and his brothers were placed among the descendants of Ulu and "the sons of Kii," and Maui was one of the ancestors of Kamehameha, the first king of the united Hawaiian Islands. This would place him in the seventh or eighth century of the Christian Era. But it is more probable that Maui belongs to the mist-land of time. His mischievous pranks with the various gods would make him another Mercury living in any age from the creation to the beginning of the Christian era.

The Hervey Island legends state that Maui's father was "the supporter of the heavens" and his mother "the guardian of the road to the invisible world." In the Hawaiian chant, Akalana was the name of his father. In other groups this was the name by which his mother was known. Kanaloa, the god, is sometimes known as the father of Maui. In Hawai`i Hina was his mother. Elsewhere Ina, or Hina, was the grandmother, from whom he secured fire.

The Hervey Island legends say that four mighty ones lived in the old world from which their ancestors came. This old world bore the name Ava-iki, which is the same as Hawa-ii, or Hawaii. The four gods were Mauike, Ra, Ru, and Bua-Taranga.

It is interesting to trace the connection of these four names with Polynesian mythology. Mauike is the same as the demi-god of New Zealand, Mafuike. On other islands the name is spelled Mauika, Mafuika, Mafuia, Mafuie, and Mahuika. Ra, the sun god of Egypt, is the same as Ra in New Zealand and La (sun) in Hawaii. Ru, the supporter of the heavens, is probably the Ku of Hawaii, and the Tu of New Zealand and other islands, one of the greatest of the gods worshipped by the ancient Hawaiians. The fourth mighty one from Ava-ika was a woman, Bua-taranga, who guarded the path to the underworld. Talanga in Samoa, and Akalana in Hawaii were the same as Taranga. Pua-kalana (the Kalana flower) would probably be the same in Hawaiian as Buataranga in the language of the Society Islands.

Ru, the supporter of the heavens, married Buataranga, the guardian of the lower world. Their one child was Maui. The legends of Raro-Tonga state that Maui's father and mother were the children of Tangaroa (Kanaloa in Hawaiian), the great god worshipped throughout Polynesia. There were three Maui brothers and one sister, Ina-ika (Ina, the fish).

The New Zealand legends relate the incidents of the babyhood of Maui.

Maui was prematurely born, and his mother, not caring to be troubled with him, cut off a lock of her hair, tied it around him and cast him into the sea. In this way the name came to him, Maui-tikitiki, or "Maui formed in the topknot." The waters bore him safely. The jelly fish enwrapped and mothered him. The god of the seas cared for and protected him. He was carried to the god's house and hung up in the roof that he might feel the warm air of the fire, and be cherished into life. When he was old enough, he came to his relations while they were all gathered in the great House of Assembly, dancing and making merry. Little Maui crept in and sat down behind his brothers. Soon his mother called the children and found a strange child, who proved that he was her son, and was taken in as one of the family. Some of the brothers were jealous, but the eldest addressed the others as follows:

"Never mind; let him be our dear brother. In the days of peace remember the proverb, 'When you are on friendly terms, settle your disputes in a friendly way; when you are at war, you must redress your injuries by violence.' It is better for us, brothers, to be kind to other people. These are the ways by which men gain influence by laboring for abundance of food to feed others, by collecting property to give to others, and by similar means by which you promote the good of others."

Thus, according to the New Zealand story related by Sir George Grey, Maui was received in his home. Maui's home was placed by some of the Hawaiian myths at Kauiki, a foothill of the great extinct crater Haleakala, on the Island of Maui. It was here he lived when the sky was raised to its present position. Here was located the famous fort around which many battles were fought during the years immediately preceding the coming of Captain Cook. This fort was held by warriors of the Island of Hawaii a number of years. It was from this home that Maui was supposed to have journeyed when he climbed Mt. Haleakala to ensnare the sun.

And yet most of the Hawaiian legends place Maui's home by the rugged black lava beds of the Wailuku river near Hilo on the island of Hawaii. Here he lived when he found the way to make fire by rubbing sticks together, and when he killed Kuna, the great eel, and performed other feats of valor. He was supposed to cultivate the land on the north side of the river. His mother, usually known as Hina, had her home in a lava cave under the beautiful Rainbow Falls, one of the fine scenic attractions of Hilo. An ancient demigod, wishing to destroy this home, threw a great mass of lava across the stream below the falls. The rising water was fast filling the cave.

Hina called loudly to her powerful son Maui. He came quickly and found that a large and strong ridge of lava lay across the stream. One end rested against a small hill. Maui struck the rock on the other side of the hill and thus broke a new pathway for the river. The water swiftly flowed away and the cave remained as the home of the Maui family.

According to the King Kalakaua family legend, translated by Queen Liliuokalani, Maui and his brothers also made this place their home. Here he aroused the anger of two uncles, his mother's brothers, who were called "Tall Post" and "Short Post," because they guarded the entrance to a cave in which the Maui family probably had its home.

"They fought hard with Maui, and were thrown, and red water flowed freely from Maui's forehead. This was the first shower by Maui." Perhaps some family discipline followed this knocking down of door posts, for it is said:

Haul's mother, so says a New Zealand legend, had her home in the under-world as well as with her children. Maui determined to find the hidden dwelling place. His mother would meet the children in the evening and lie down to sleep with them and then disappear with the first appearance of dawn. Maui remained awake one night, and when all were asleep, arose quietly and stopped up every crevice by which a ray of light could enter. The morning came and the sun mounted up far up in the sky. At last his mother leaped up and tore away the things which shut out the light.

"Oh, dear; oh, dear! She saw the sun high in the heavens; so she hurried away, crying at the thought of having been so badly treated by her own children." Maui watched her as she pulled up a tuft of grass and disappeared in the earth, pulling the grass back to its place.

Thus Maui found the path to the under-world. Soon he transformed himself into a pigeon and flew down, through the cave, until he saw a party of people under a sacred tree, like those growing in the ancient first Hawaii. He flew to the tree and threw down berries upon the people. They threw back stones. At last he permitted a stone from his father to strike him, and he fell to the ground. "They ran to catch him, but lo! the pigeon had turned into a man."

Then his father "took him to the water to be baptized" (possibly a modern addition to the legend). Prayers were offered and ceremonies passed through. But the prayers were incomplete and Maui's father knew that the gods would be angry and cause Maui's death, and all because in the hurried baptism a part of the prayers had been left unsaid. Then Maui returned to the upper world and lived again with his brothers.

Maui commenced his mischievous life early, for Hervey Islanders say that one day the children were playing a game dearly loved by Polynesians hide and seek. Here a sister enters into the game and hides little Maui under a pile of dry sticks. His brothers could not find him, and the sister told them where to look. The sticks were carefully handled, but the child could not be found. He had shrunk himself so small that he was like an insect under some sticks and leaves. Thus early he began to use enchantments.

Maui's home, at the best, was only a sorry affair. Gods and demi-gods lived in caves and small grass houses. The thatch rapidly rotted and required continual renewal. In a very short time the heavy rains beat through the decaying roof. The home was without windows or doors, save as low openings in the ends or sides allowed entrance to those willing to crawl through. Off on one side would be the rude shelter, in the shadow of which Hina pounded the bark of certain trees into wood pulp and then into strips of thin, soft wood-paper, which bore the name of "Kapa cloth." This cloth Hina prepared for the clothing of Maui and his brothers. Kapa cloth was often treated to a coat of coco-nut, or candle-nut oil, making it somewhat waterproof and also more durable.

Here Maui lived on edible roots and fruits and raw fish, knowing little about cooked food, for the art of fire-making was not yet known. In later years Maui was supposed to live on the eastern end of the island Maui, and also in another home on the large island Hawaii, on which he discovered how to make fire by rubbing dry sticks together. Maui was the Polynesian Mercury. As a little fellow he was endowed with peculiar powers, permitting him to become invisible or to change his human form into that of an animal. He was ready to take anything from any one by craft or force. Nevertheless, like the thefts of Mercury, his pranks usually benefited mankind.

It is a little curious that around the different homes of Maui, there is so little record of temples and priests and altars. He lived too far back for priestly customs. His story is the rude, mythical survival of the days when of church and civil government there was none and worship of the gods was practically unknown, but every man was a law unto himself, and also to the other man, and quick retaliation followed any injury received. Back to Contents

MAUI THE FISHERMAN

One of Haul's homes was near Kauiki, a place well known throughout the Hawaiian Islands because of its strategic importance. For many years it was the site of a fort around which fierce batties were fought by the natives of the island Maui, repelling the invasions of their neighbors from Hawaii.

Haleakala (the House of the Sun), the mountain from which Maui the demi-god snared the sun, looks down ten thousand feet upon the Kauiki headland. Across the channel from Haleakala rises Mauna Kea, " The White Mountain " the snow-capped which almost all the year round rears its white head in majesty among the clouds.

In the snowy breakers of the surf which washes the beach below these mountains, are broken coral reefs the fishing grounds of the Hawaiians. Here near Kauiki, according to some Hawaiian legends, Maui's mother Hina had her grass house and made and dried her kapa cloth. Even to the present day it is one of the few places in the islands where the kapa is still pounded into sheets from the bark of the hibiscus and kindred trees.

Here is a small bay partially reef-protected, over which year after year the moist clouds float and by day and by night crown the waters with rainbows the legendary sign of the home of the deified ones. Here when the tide is out the natives wade and swim, as they have done for centuries, from coral block to coral block, shunning the deep resting places of their dread enemy, the shark, sometimes esteemed divine. Out on the edge of the outermost reef they seek the shellfish which cling to the coral, or spear the large fish which have been left in the beautiful little lakes of the reef. Coral land is a region of the sea coast abounding in miniature lakes and rugged valleys and steep mountains. Clear waters with every motion of the tide surge in and out through sheltered caves and submarine tunnels, according to an ancient Hawaiian song:

"Never quiet, never failing, never sleeping, Never very noisy is the sea of the sacred caves."

Sea mosses of many hues are the forests which drape the hillsides of coral land and reflect the colored rays of light which pierce the ceaselessly moving waves. Down in the beautiful little lakes, under overhanging coral cliffs, darting in and out through the fringes of seaweed, the purple mullet and royal red fish flash before the eyes of the fisherman. Sometimes the many-tinted glorious fish of paradise reveal their beauties, and then again a school of black and gold citizens of the reef follow the tidal waves around projecting crags and through the hidden tunnels from lake to lake, while above the fisherman follows spearing or snaring as best he can. Maui's brothers were better fishermen than he. They sought the deep sea beyond the reef and the larger fish. They made hooks of bone or of mother of pearl, with a straight, slender, sharp-pointed piece leaning backward at a sharp angle. This was usually a consecrated bit of bone or mother of pearl, and was supposed to have peculiar power to hold fast any fish which had taken the bait.

In the Sea of Sacred Caves

These bones were usually taken from the body of some one who while living had been noted for great power or high rank. This sharp piece was tightly tied to the larger bone or shell, which formed the shank of the hook. The sacred barb of Maui's hook was a part of the magic bone he had secured from his ancestors in the under-world the bone with which he struck the sun while lassooing him and compelling him to move more slowly through the heavens.

"Earth-twisted" fibres of vines twisted while growing, was the cord used by Maui in tying the parts of his magic hook together. Long and strong were the fish lines made from the olona fibre, holding the great fish caught from the depths of the ocean. The fibres of the olona vine were among the longest and strongest threads found in the Hawaiian Islands.

Such a hook could easily be cast loose by the struggling fish, if the least opportunity were given. Therefore it was absolutely necessary to keep the line taut, and pull strongly and steadily, to land the fish in the canoe.

Maui did not use his magic hook for a long time. He seemed to understand that it would not answer ordinary needs. Possibly the idea of making the supernatural hook did not occur to him until he had exhausted his lower wit and magic upon his brothers.

It is said that Maui was not a very good fisherman. Sometimes his end of the canoe contained fish which his brothers had thought were on their hooks until they were landed in the canoe.

Many times they laughed at him for his poor success, and he retaliated with his mischievous tricks.

"E !" he would cry, when one of his brothers began to pull in, while the other brothers swiftly paddled the canoe forward. "E ! See we both have caught great fish at the same moment. Be careful now. Your line is loose. Look out ! Look out."

All the time he would be pulling his own line in as rapidly as possible. Onward rushed the canoe. Each fisherman shouting to encourage the others. Soon the lines by the tricky manipulation of Maui would be crossed. Then as the great fish was brought near the side of the boat Maui the little, the mischievous one, would slip his hook toward the head of the fish and flip it over into the canoe causing his brother's line to slacken for a moment. Then his mournful cry rang out: "Oh, my brother, your fish is gone. Why did you not pull more steadily? It was a fine fish, and now it is down deep in the waters." Then Maui held up his splendid catch (from his brother's hook) and received somewhat suspicious congratulations. But what could they do? Maui was the smart one of the family.

Their father and mother were both members of the household of the gods. The father was "the supporter of the heavens" and the mother was "the guardian of the way to the invisible world," but pitifully small and very few were the gifts bestowed upon their children. Maui's brothers knew nothing beyond the average home life of the ordinary Hawaiian, and Maui alone was endowed with the power to work miracles. Nevertheless the student of Polynesian legends learns that Maui is more widely known than almost all the demi-gods of all nations as a discoverer of benefits for his fellows, and these physical rather than spiritual. After many fishing excursions Maui's brothers seemed to have wit enough to understand his tricks, and thenceforth they refused to take him in their canoe when they paddled out to the deep-sea fishing grounds. Then those who depended upon Maui to supply their daily needs murmured against his poor success. His mother scolded him and his brothers ridiculed him.

In some of the Polynesian legends it is said that his wives and children complained because of his laziness and at last goaded him into a new effort.

The ex-Queen Liliuokalani, in a translation of what is called "the family chant," says that Maui's mother sent him to his father for a hook with which to supply her need.

When Maui had obtained his hook, he tried to go fishing with his brothers. He leaped on the end of their canoe as they pushed out into deep water. They were angry and cried out: "This boat is too small for another, Maui." So they threw him off and made him swim back to the beach. When they returned from their day's work, they brought back only a shark. Maui told them if he had been with them better fish would have been upon their hooks the Ulua, for instance, or, possibly, the Pimoe the king of fish. At last they let him go far out outside the harbor of Kipahula to a place opposite Ka Iwi o Pele, "The bone of Pele," a peculiar piece of lava lying near the beach at Hana on the eastern side of the island Maui. There they fished, but only sharks were caught. The brothers ridiculed Maui, saying: "W"here are the Ulua, and where is Pimoe?"

Then Maui threw his magic hook into the sea, baited with one of the Alae birds, sacred to his mother Hina. He used the incantation, "When I let go my hook with divine power, then I get the great Ulua."

The bottom of the sea began to move. Great waves arose, trying to carry the canoe away. The fish pulled the canoe two days, drawing the line to its fullest extent. When the slack began to come in the line, because of the tired fish, Maui called for the brothers to pull hard against the coming fish. Soon land rose out of the water. Maui told them not to look back or the fish would be lost. One brother did look back the line slacked, snapped, and broke, and the land lay behind them in islands.

One of the Hawaiian legends also says that while the brothers were paddling in full strength, Maui saw a calabash floating in the water. He lifted it into the canoe, and behold! his beautiful sister Hina of the sea. The brothers looked, and the separated islands lay behind them, free from the hook, while Cocoanut Island the dainty spot of beauty in Hilo harbor was drawn up a little ledge of lava in later years the home of a cocoanut grove.

The better, the more complete, legend comes from New Zealand, which makes Maui so mischievous that his brothers refuse his companionship and therefore, thrown on his own resources, he studies how to make a hook which shall catch something worth while. In this legend Maui is represented as making his own hook and then pleading with his brothers to let him go with them once more. But they hardened their hearts against him, and refused again and again.

Maui possessed the power of changing himself into different forms. At one time while playing with his brothers he had concealed himself for them to find. They heard his voice in a corner of the house but could not find him. Then under the mats on the floor, but again they could not find him. There was only an insect creeping on the floor. Suddenly they saw their little brother where the insect had been. Then they knew he had been tricky with them. So in these fishing days he resolved to go back to his old ways and cheat his brothers into carrying him with them to the great fishing grounds.

Sir George Grey says that the New Zealand Maui went out to the canoe and concealed himself as an insect in the bottom of the boat so that when the early morning light crept over the waters and his brothers pushed the canoe into the surf they could not see him. They rejoiced that Maui did not appear, and paddled away over the waters.

They fished all day and all night and on the morning of the next day, out from among the fish in the bottom of the boat came their troublesome brother.

They had caught many fine fish and were satisfied, so thought to paddle homeward; but their younger brother pleaded with them to go out, far out, to the deeper seas and permit him to cast his hook. He said he wanted larger and better fish than any they had captured.

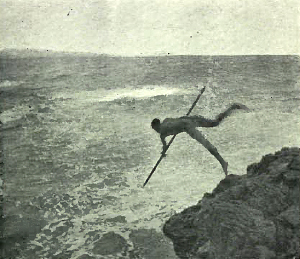

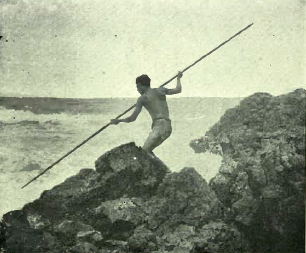

Spearing Fish

So they paddled to their outermost fishing grounds but this did not satisfy Maui

It was evidently easier to work for him than to argue with him therefore far out in the sea they went. The home land disappeared from view; they could see only the outstretching waste of waters. Maui urged them out still farther. Then he drew his magic hook from under his malo or loin-cloth. The brothers wondered what he would do for bait. The New Zealand legend says that he struck his nose a mighty blow until the blood gushed forth. When this blood became clotted, he fastened it upon his hook and let it down into the deep sea.

Down it went to the very bottom and caught the under world. It was a mighty fish but the brothers paddled with all their might and main and Maui pulled in the line. It was hard rowing against the power which held the hook down in the sea depths but the brothers became enthusiastic over Maui's large fish, and were generous in their strenuous endeavors. Every muscle was strained and every paddle held strongly against the sea that not an inch should be lost. There was no sudden leaping and darting to and fro, no "give" to the line; no "tremble" as when a great fish would shake itself in impotent wrath when held captive by a hook. It was simply a struggle of tense muscle against an immensely heavy dead weight. To the brothers there came slowly the feeling that Maui was in one of his strange moods and that something beyond their former experiences with their tricky brother was coming to pass.

At last one of the brothers glanced backward. With a scream of intense terror he dropped his paddle. The others also looked. Then each caught his paddle and with frantic exertion tried to force their canoe onward. Deep down in the heavy waters they pushed their paddles. Out of the great seas the black, ragged head of a large island was rising like a fish it seemed to be chasing them through the boiling surf. In a little while the water became shallow around them, and their canoe finally rested on a black beach.

Maui for some reason left his brothers, charging them not to attempt to cut up this great fish. But the unwise brothers thought they would fill the canoe with part of this strange thing which they had caught. They began to cut up the back and put huge slices into their canoe. But the great fish the island shook under the blows and with mighty earthquake shocks tossed the boat of the brothers, and their canoe was destroyed. As they were struggling in the waters, the great fish devoured them. The island came up more and more from the waters but the deep gashes made by Haul's brothers did not heal they became the mountains and valleys stretching from sea to sea.

White of New Zealand says that Maui went down into the underworld to meet his great ancestress, who was one side dead and one side alive. From the dead side he took the jaw bone, made a magic hook, and went fishing. When he let the hook down into the sea, he called:

Thus he pulled up Ao-tea-roa one of the large islands of New Zealand. On it were houses, with people around them. Fires were burning. Maui walked over the island, saw with wonder the strange men and the mysterious fire. He took fire in his hands and was burned. He leaped into the sea, dived deep, came up with the other large island on his shoulders. This island he set on fire and left it always burning. It is said that the name for New Zealand given to Captain Cook was Te ika o Maui, "The fish of Maui." Some New Zealand natives say that he fished up the island on which dwelt "Great Hina of the Night," who finally destroyed Maui while he was seeking immortality.

One legend says that Maui fished up apparently from New Zealand the large island of the Tongas. He used this chant:

This is an excellent poetical description of the great fish delaying the quick hard bite. Then the island comes to the surface and Maui, the beloved grandchild of the Polynesian god Kanaloa, is praised.

It was part of one of the legends that Maui changed himself into a bird and from the heavens let down a line with which he drew up land, but the line broke, leaving islands rather than a mainland. About two hundred lesser gods went to the new islands in a large canoe. The greater gods punished them by making them mortal.

Turner, in his book on Samoa, says there were three Mauis, all brothers. They went out fishing from Rarotonga. One of the brothers begged the "goddess of the deep rocks" to let his hooks catch land. Then the island Manahiki was drawn up. A great wave washed two of the Mauis away. The other Maui found a great house in which eight hundred gods lived. Here he made his home until a chief from Rarotonga drove him away. He fled into the sky, but as he leaped he separated the land into two islands.

Other legends of Samoa say that Tangaroa, the great god, rolled stones from heaven. One became the island Savaii, the other became Upolu. A god is sometimes represented as passing over the ocean with a bag of sand. Wherever he dropped a little sand islands sprang up.

Paton, the earnest and honored missionary of the New Hebrides Islands, evidently did not know of the name Mauitikitiki, so he spells the name of the fisherman Ma-tshi-ktshi-ki, and gives the myth of the fishing up of the various islands. The natives said that Maui left footprints on the coral reefs of each island where he stood straining and lifting in his endeavors to pull up each other island. He threw his line around a large island intending to draw it up and unite it with the one on which he stood, but his line broke. Then he became angry and divided into two parts the island on which he stood. This same Maui is recorded by Mr. Paton as being in a flood which put out one volcano Maui seized another, sailed across to a neighboring island and piled it upon the top of the volcano there, so the fire was placed out of reach of the flood.

In the Hervey Group of the Tahitian or Society Islands the same story prevails and the natives point out the place where the hook caught and a print was made by the foot in the coral reef. But they add some very mythical details. Maui's magic fish-hook is thrown into the skies, where it continuously hangs, the curved tail of the constellation which we call Scorpio. Then one of the gods becoming angry with Maui seized him and threw him also among the stars. There he stays looking down upon his people. He has become a fixed part of the scorpion itself.

The Hawaiian myths sometimes represent Maui as trying to draw the islands together while fishing them out of the sea. When they had pulled up the island of Kauai they looked back and were frightened. They evidently tried to rush away from the new monster and thus broke the line. Maui tore a side out of the small crater Kaula when trying to draw it to one of the other islands. Three aumakuas, three fishes supposed to be spirit-gods, guarded Kaula and defeated his purpose. At Hawaii Cocoanut Island broke off because Maui pulled too hard. Another place near Hilo on the large island of Hawaii where the hook was said to have caught is in the Wailuku river below Rainbow Falls.

Maui went out from his home at Kauiki, fishing with his brothers. After they had caught some fine fish the brothers desired to return, but Maui persuaded them to go out farther. Then when they became tired and determined to go back, he made the seas stretch out and the shores recede until they could see no land. Then drawing the magic hook, he baited it with the Alae or sacred mud hen belonging to his Mother Hina. Queen Liliuokalani 's family chant has the following reference to this myth :

Maui evidently had no scruples against using anything which would help him carry out his schemes. He indiscriminately robbed his friends and the gods alike.

Down in the deep sea sank the hook with its struggling bait, until it was seized by "the land under the water. ' '

But Hina the mother saw the struggle of her sacred bird and hastened to the rescue. She caught a wing of the bird, but could not pull the Alae from the sacred hook. The wing was torn off. Then the fish gathered around the bait and tore it in pieces. If the bait could have been kept entire, then the land would have come up in a continent rather than as an island. Then the Hawaiian group would have been unbroken. But the bait broke and the islands came as fragments from the under world.

Maui's hook and canoe are frequently mentioned in the legends. The Hawaiians have a long rock in the Wailuku river at Hilo which they call Maui's canoe. Different names were given to Maui's canoe by the Maoris of New Zealand. "Vine of Heaven," "Prepare for the North," "Land of the Receding Sea." His fish hook bore the name "Plume of Beauty."

On the southern end of Hawke's Bay, New Zealand, there is a curved ledge of rocks extending out from the coast. This is still called by the Maoris "Maui's fish-hook," as if the magic hook had been so firmly caught in the jaws of the island that Maui could not disentangle it, but had been compelled to cut it off from his line.

There is a large stone on the sea coast of North Kohala on the island of Hawaii which the Hawaiians point out as the place where Maui's magic hook caught the island and pulled it through the sea.

In the Tonga Islands, a place known as Hounga is pointed out by the natives as the spot where the magic hook caught in the rocks. The hook itself was said to have been in the possession of a chief-family for many generations.

Another group of Hawaiian legends, very incomplete, probably referring to Maui, but ascribed to other names, relates that a fisherman caught a large block of coral. He took it to his priest. After sacrificing, and consulting the gods, the priest advised the fisherman to throw the coral back into the sea with incantations. While so doing this block became Hawaii-loa. The fishing continued and blocks of coral were caught and thrown back into the sea until all the islands appeared. Hints of this legend cling to other island groups as well as to the Hawaiian Islands. Fornander credits a fisherman from foreign lands as thus bringing forth the Hawaiian Islands from the deep seas. The reference occurs in part of a chant known as that of a friend of Paao the priest who is supposed to have come from Samoa to Hawaii in the eleventh century. This priest calls for his companions: :

Here are the canoes.

The god Kanaloa is sometimes known as a ruler of the under-world, whose land was caught by Maui's hook and brought up in islands. Thus in the legends the thought has been perpetuated that some one of the ancestors of the Polynesians made voyages and discovered islands.

In the time of Umi, King of Hawaii, there is the following record of an immense bone fish-hook, which was called the ' ' fish-hook of Maui :' '

"In the night of Muku (the last night of the month), a priest and his servants took a man, killed him, and fastened his body to the hook, which bore the name Manai-a-ka-lani, and dragged it to the heiau (temple) as a fish, and placed it on the altar.

This hook was kept until the time of Kamehameha I. From time to time he tried to break it, and pulled until he perspired.

Peapea, a brother of Kaahumanu, took the hook and broke it. He was afraid that Kamehameha would kill him. Kaahumanu, however, soothed the King, and he passed the matter over. The broken bone was probably thrown away. Back to Contents

MAUI LIFTING THE SKY

MAUI 'S home was for a long time enveloped by darkness. The heavens had fallen down, or, rather, had not been separated from the earth. According to some legends, the skies pressed so closely and so heavily upon the earth that when the plants began to grow, all the leaves were necessarily flat. According to other legends, the plants had to push up the clouds a little, and thus caused the leaves to flatten out into larger surface, so that they could better rive the skies back and hold them in place. Thus the leaves became flat at first, and have so remained through all the days of mankind. The plants lifted the sky inch by inch until men were able to crawl about between the heavens and the earth, and thus pass from place to place and visit one another.

After a long time, according to the Hawaiian legends, a man, supposed to be Maui, came to a woman and said: "Give me a drink from your gourd cala bash, and I will push the heavens higher." The woman handed the gourd to him. When he had taken a deep draught, he braced himself against the clouds and lifted them to the height of the trees. Again he hoisted the sky and carried it to the tops of the mountains; then with great exertion he thrust it upwards once more, and pressed it to the place it now occupies. Nevertheless dark clouds many times hang low along the eastern slope of Maui's great mountain Haleakala and descend in heavy rains upon the hill Kauwiki ; but they dare not stay, lest Maui the strong come and hurl them so far away that they cannot come back again.

A man who had been watching the process of lifting the sky ridiculed Maui for attempting such a difficult task. When the clouds rested on the tops of the mountains, Maui turned to punish his critic. The man had fled to the other side of the island. Maui rapidly pursued and finally caught him on the sea coast, not many miles north of the town now known as Lahaina. After a brief struggle the man was changed, according to the story, into a great black rock, which can be seen by any traveller who desires to localize the legends of Hawaii.

In Samoa Tiitii, the latter part of the full name of Mauikiikii, is used as the name of the one who braced his feet against the rocks and pushed the sky up. The foot-prints, some six feet long, are said to be shown by the natives.

Another Samoan story is almost like the Hawaiian legend. The heavens had fallen, people crawled, but the leaves pushed up a little; but the sky was uneven. Men tried to walk, but hit their heads, and in this confined space it was very hot. A woman rewarded a man who lifted the sky to its proper place by giving him a drink of water from her cocoanut shell.

A number of small groups of islands in the Pacific have legends of their skies being lifted, but they attribute the labor to the great eels and serpents of the sea.

One of the Ellice group, Niu Island, says that as the serpent began to lift the sky the people clapped their hands and shouted "Lift up!" "High!" "Higher!" But the body of the serpent finally broke into pieces which became islands, and the blood sprinkled its drops on the sky and became stars.

One of the Samoan legends says that a plant called daiga, which had one large umbrella-like leaf, pushed up the sky and gave it its shape.

The Vatupu, or Tracey Islanders, said at one time the sky and rocks were united. Then steam or clouds of smoke rose from the rocks, and, pouring out in volumes, forced the sky away from the earth. Man appeared in these clouds of steam or smoke. Perspiration burst forth as this man forced his way through the heated atmosphere. From this perspiration woman was formed. Then were born three sons, two of whom pushed up the sky. One, in the north, pushed as far as his arms would reach. The one in the south was short and climbed a hill, pushing as he went up, until the sky was in its proper place.

The Gilbert Islanders say the sky was pushed up by men with long poles.

The ancient New Zealanders understood incantations by which they could draw up or discover. They found a land where the sky and the earth were united. They prayed over their stone axe and cut the sky and land apart. "Hau-hau-tu" was the name of the great stone axe by which the sinews of the great heaven above were severed, and Rangi (sky) was separated from Papa (earth).

The New Zealand Maoris were accustomed to say that at first the sky rested close upon the earth and therefore there was utter darkness for ages. Then the six sons of heaven and earth, born during this period of darkness, felt the need of light and discussed the necessity of separating their parents the sky from the earth and decided to attempt the work.

Kongo (Hawaiian god Lono) the "father of food plants," attempted to lift the sky, but could not tear it from the earth. Then Tangaroa (Kanaloa), the "father of fish and reptiles," failed. Haumia Tiki-tiki who was the "father of wild food plants," could not raise the clouds. Then Tu (Hawaiian Ku), the "father of fierce men," struggled in vain. But Tane (Hawaiian Kane), the "father of giant forests," pushed and lifted until he thrust the sky far up above him. Then they discovered their descendants the multitude of human beings who had been living on the earth concealed and crushed by the clouds. Afterwards the last son, Tawhiri (father of storms), was angry and waged war against his brothers. He hid in the sheltered hollows of the great skies. There he begot his vast brood of winds and storms with which he finally drove all his brothers and their descendants into hiding places on land and sea. The New Zealanders mention the names of the canoes in which their ancestors fled from the old home Hawaiki.

Tu (father of fierce men) and his descendants, however, conquered wind and storm and have ever since held supremacy.

The New Zealand legends also say that heaven and earth have never lost their love for each other. "The warm sighs of earth ever ascend from the wooded mountains and valleys, and men call them mists. The sky also lets fall frequent tears which men term dew drops."

The Manihiki islanders say that Maui desired to separate the sky from the earth. His father ( Ru, was the supporter of the heavens. Maui persuaded him to assist in lifting the burden. Maui went to the north and crept into a place, where, lying prostrate under the sky, he could brace himself against it and push with great power. In the same way Ru went to the south and braced himself against the southern skies. Then they made the signal, and both pressed "with their backs against the solid blue mass." It gave way before the great strength of the father and son. Then they lifted again, bracing themselves with hands and knees against the earth. They crowded it and bent it upward. They were able to stand with the sky resting on their shoulders. They heaved against the bending mass, and it receded rapidly. They quickly put the palms of their hands under it; then the tips of their fingers, and it retreated farther and farther. At last, "drawing themselves out to gigantic proportions, they pushed the entire heavens up to the very lofty position which they have ever since occupied."

But Maui and Ru had not worked perfectly together; therefore the sky was twisted and its surface was very irregular. They determined to smooth the sky before they finished their task, so they took large stone adzes and chipped off the rough protuberances and ridges, until by and by the great arch was cut out and smoothed off. They then took finer tools and chipped and polished until the sky became the beautifully finished blue dome which now bends around the earth.

The Hervey Island myth, as related by "W. W. Gill, states that Ru, the father of Maui, came from Avaiki (Hawa-iki), the underworld or abode of the spirits of the dead. He found men crowded down by the sky, which was a mass of solid blue stone. He was very sorry when he saw the condition of the inhabitants of the earth, and planned to raise the sky a little. So he planted stakes of different kinds of trees. These were strong enough to hold the sky so far above the earth 'that men could stand erect and walk about without inconvenience." This was celebrated in one of the Hervey Island songs:

For this helpful deed Ru received the name "The supporter of the heavens." He was rather proud of his achievement and was gratified because of the praise received. So he came sometimes and looked at the stakes and the beautiful blue sky resting on them. Maui, the son, came along and ridiculed his father for thinking so much of his work. Maui is not represented, in the legends, as possessing a great deal of love and reverence for his relatives provided his affection interfered with his mischief; so it was not at all strange that he laughed at his father. Ru became angry and said to Maui: "Who told youngsters to talk? Take care of yourself, or I will hurl you out of existence."

Maui dared him to try it. Ru quickly seized him and "threw him to a great height." But Maui changed himself to a bird and sank back to earth unharmed.

Then he changed himself back into the form of a man, and, making himself very large, ran and thrust his head between the old man's legs. He pried and lifted until Ru and the sky around him began to give. Another lift and he hurled them both to such a height that the sky could not come back.

Ru himself was entangled among the stars. His head and shoulders stuck fast, and he could not free himself. How he struggled, until the skies shook, while Maui went away. Maui was proud of his achievement in having moved the sky so far away. In this self-rejoicing he quickly forgot his father.

Ru died after a time. "His body rotted away and his bones, of vast proportions, came tumbling down from time to time, and were shivered on the earth into countless fragments. These shattered bones of Ru are scattered over every hill and valley of one of the islands, to the very edge of the sea."

Thus the natives of the Hervey Islands account for the many pieces of porous lava and the small pieces of pumice stone found occasionally in their islands. The "bones" were very light and greatly resembled fragments of real bone. If the fragments were large enough they were sometimes taken and worshiped as gods. One of these pieces, of extraordinary size, was given to Mr. Gill when the natives were bringing in a large collection of idols. "This one was known as 'The Light Stone,' and was worshiped as the god of the wind and the waves. Upon occasions of a hurricane, incantations and offerings of food would be made to it."

Thus, according to different Polynesian legends, Maui raised the sky and made the earth inhabitable or his fellow-men. Back to Contents

MAUI SNARING THE SUN

A very unique legend is found among the widely-scattered Polynesians. The story of Maui's "Snaring the Sun" was told among the Maoris of New Zealand, the Kanakas of the Hervey and Society Islands, and the ancient natives of Hawaii. The Samoans tell the same story without mentioning the name of Maui. They say that the snare was cast by a child of the sun itself. The Polynesian stories of the origin of the sun are worthy of note before the legend of the change from short to long days is given.

The Rarotongans, according to W. "W. Gill, tell the story of the origin of the sun and moon. They say that Vatea (Wakea) and their ancestor Tongaiti quarreled concerning a child each claiming it as his own. In the struggle the child was cut in two. Vatea squeezed and rolled the part he secured into a ball and threw it away, far up into the heavens, where it became the sun. It shone brightly as it rolled along the heavens, and sank down to Avaiki (Hawaiki), the nether world. But the ball came back again and once more rolled across the sky. Tonga-iti had let his half of the child fall on the ground and lie there, until made envious by the beautiful ball Vatea made.

At last he took the flesh which lay on the ground and made it into a ball. As the sun sank he threw his ball up into the darkness, and it rolled along the heavens, but the blood had drained out of the flesh while it lay upon the ground, therefore it could not become so red and burning as the sun, and had not life to move so swiftly. It was as white as a dead body, because its blood was all gone; and it could not make the darkness flee away as the sun had done. Thus day and night and the sun and moon always remain with the earth.

The legends of the Society Islands say that a demon in the west became angry with the sun and in his rage ate it up, causing night. In the same way a demon from the east would devour the moon, but for some reason these angry ones could not destroy their captives and were compelled to open their mouths and let the bright balls come forth once more. In some places a sacrifice of some one of distinction was needed to placate the wrath of the devourers and free the balls of light in times of eclipse.

The moon, pale and dead in appearance, moved slowly; while the sun, full of life and strength, moved quickly. Thus days were very short and nights were very long. Mankind suffered from the fierceness of the heat of the sun and also from its prolonged absence. Day and night were alike a burden to men. The darkness was so great and lasted so long that ruits would not ripen.

After Maui had succeeded in throwing the heavens into their place, and fastening them so that they could not fall, he learned that he had opened a way for the sun-god to come up from the lower world and rapidly run across the blue vault. This made two troubles for men the heat of the sun was very great and the journey too quickly over. Maui planned to capture the sun and punish him for thinking so little about the welfare of mankind.

As Rev. A. O. Forbes, a missionary among the Hawaiians, relates, Maui's mother was troubled very much by the heedless haste of the sun. She had many kapa-cloths to make, for this was the only kind of clothing known in Hawaii, except sometimes a woven mat or a long grass fringe worn as a skirt. This native cloth was made by pounding the fine bark of certain trees with wooden mallets until the fibres were beaten and ground into a wood pulp. Then she pounded the pulp into thin sheets from which the best sleeping mats and clothes could be fashioned. These kapa cloths had to be thoroughly dried, but the days were so short that by the time she had spread out the kapa the sun had heedlessly rushed across the sky and gone down into the under-world, and all the cloth had to be gathered up again and cared for until another day should come. There were other troubles. "The food could not be prepared and cooked in one day. Even an incantation to the gods could not be chanted through ere they were overtaken by darkness."

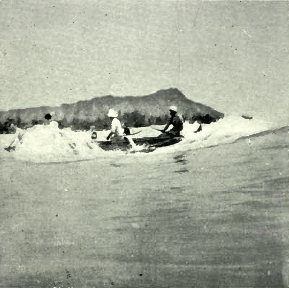

Iao Mountain from the Sea

This was very discouraging and caused great suffering, as well as much unnecessary trouble and labor. Many complaints were made against the thoughtless sun.

Maui pitied his mother and determined to make the sun go slower that the days might be long enough to satisfy the needs of men. Therefore, he went over to the northwest of the island on which he lived. This was Mt. lao, an extinct volcano, in which lies one of the most beautiful and picturesque valleys of the Hawaiian Islands. He climbed the ridges until he could see the course of the sun as it passed over the island. He saw that the sun came up the eastern side of Mt. Haleakala. He crossed over the plain between the two mountains and climbed to the top of Mt. Haleakala. There he watched the burning sun as it came up from Koolau and passed directly over the top of the mountain. The summit of Haleakala is a great extinct crater twenty miles in circumference, and nearly twenty-five hundred feet in depth. There are two tremendous gaps or chasms in the side of the crater wall, through which in days gone by the massive bowl poured forth its flowing lava. One of these was the Koolau, or eastern gap, in which Maui probably planned to catch the sun.

Mt. Hale-a-ka-la of the Hawaiian Islands means House-of-the-sun. "La," or "Ra," is the name of the sun throughout parts of Polynesia. Ra was the sungod of ancient Egypt. Thus the antiquities of Polynesia and Egypt touch each other, and today no man knows the full reason thereof.

The Hawaiian legend says Maui was taunted by a man who ridiculed the idea that he could snare the sun, saying, "You will never catch the sun. You are only an idle nobody."

Maui replied, "When I conquer my enemy and my desire is attained, I will be your death. ' '

After studying the path of the sun, Maui returned to his mother and told her that he would go and cut off the legs of the sun so that he could not run so fast.

His mother said: "Are you strong enough for this work?" He said, "Yes." Then she gave him fifteen strands of well-twisted fiber and told him to go to his grandmother, who lived in the great crater of Haleakala, for the rest of the things in his conflict with the sun. She said: "You must climb the mountain to the place where a large wiliwili tree is standing. There you will find the place where the sun stops to eat cooked bananas prepared by your grandmother. Stay there until a rooster crows three times; then watch your grandmother go out to make a fire and put on food. You had better take her bananas. She will look for them and find you and ask who you are. Tell her you belong to Hina."

When she had taught him all these things, he went up the mountain to Kaupo to the place Hina had directed. There was a large wiliwili tree. Here he waited for the rooster to crow. The name of that rooster was Kalauhele-moa. When the rooster had crowed three times, the grandmother came out with a bunch of bananas to cook for the sun. She took off the upper part of the bunch and laid it down. Maui immediately snatched it away. In a moment she turned to pick it up, but could not find it. She was angry and cried out: "Where are the bananas of the sun?" Then she took off another part of the bunch, and Maui stole that. Thus he did until all the bunch had been taken away. She was almost blind and could not detect him by sight, so she sniffed all around her until she detected the smell of a man. She asked: "Who are you? To whom do you belong?" Maui replied : "I belong to Hina." '"Why have you come ?" Maui told her, "I have come to kill the sun. He goes so fast that he never dries the kapa Hina has beaten out."

The old woman gave a magic stone for a battle axe and one more rope. She taught him how to catch the sun, saying: "Make a place to hide here by this large wiliwili tree. When the first leg of the sun comes up, catch it with your first rope, and so on until you have used all your ropes. Fasten them to the tree, then take the stone axe to strike the body of the sun."

Maui dug a hole among the roots of the tree and concealed himself. Soon the first ray of light the first leg of the sun came up along the mountain side. Maui threw his rope and caught it. One by one the legs of the sun came over the edge of the crater's rim and were caught. Only one long leg was still hanging down the side of the mountain. It was hard for the sun to move that leg. It shook and trembled and tried hard to come up. At last it crept over the edge and was caught by Maui with the rope given by his grandmother.

When the sun saw that his sixteen long legs were held fast in the ropes, he began to go back down the mountain side into the sea. Then Maui tied the ropes fast to the tree and pulled until the body of the sun came up again. Brave Maui caught his magic stone club or axe, and began to strike and wound the sun, until he cried:

"Give me my life." Maui said:

"If you live, you may be a traitor. Perhaps I had better kill you."

But the sun begged for life. After they had conversed a while, they agreed that there should be a regular motion in the journey of the sun. There should be longer days, and yet half the time he might go quickly as in the winter time, but the other half he must move slowly as in summer. Thus men dwelling on the earth should be blessed.

Another legend says that he made a lasso and climbed to the summit of Mt. Haleakala. He made ready his lasso, so that when the sun came up the mountain side and rose above him he could cast the noose and catch the sun, but he only snared one of the sun's larger rays and broke it off. Again and again he threw the lasso until he had broken off all the strong rays of the sun.

Then he shouted exultantly, "Thou art my captive; I will kill thee for going so swiftly."

Then the sun said, "Let me live and thou shalt see me go more slowly hereafter. Behold, hast thou not broken off all my strong legs and left me only the weak ones?"

So the agreement was made, and Maui permitted the sun to pursue his course, and from that day he went more slowly.

Maui returned from his conflict with the sun and sought for Moemoe, the man who had ridiculed him. Maui chased this man around the island from one side to the other until they had passed through Lahaina (one of the first mission stations in 1828). There on the seashore near the large black rock of the legend of Maui lifting the sky he found Moemoe. Then they left the seashore and the contest raged up hill and down until Maui slew the man and "changed the body into a long rock, which is there to this day, by the side of the road going past Black Rock."

Before the battle with the sun occurred Maui went down into the underworld, according to the New Zealand tradition, and remained a long time with his relatives. In some way he learned that there was an enchanted jawbone in the possession of some one of his ancestors, so he waited and waited, hoping that at last he might discover it.

After a time he noticed that presents of food were being sent away to some person whom he had not met.

One day he asked the messengers, "Who is it you are taking that present of food to?"

The people answered, "It is for Muri, your ancestress."

Then he asked for the food, saying, "I will carry it to her myself."

But he took the food away and hid it. "And this he did for many days," and the presents failed to reach the old woman.

By and by she suspected mischief, for it did not seem as if her friends would neglect her so long a time, so she thought she would catch the tricky one and eat him. She depended upon her sense of smell to detect the one who had troubled her. As Sir George Grey tells the story: "When Maui came along the path carrying the present of food, the old chiefess sniffed and sniffed until she was sure that she smelt some one coming. She was very much exasperated, and her stomach began to distend itself that she might be ready to devour this one when he came near.

Then she turned toward the south and sniffed and not a scent of anything reached her. Then she turned to the north, and to the east, but could not detect the odor of a human being. She made one more trial and turned toward the west. Ah! then came the scent of a man to her plainly and she called out 'I know, from the smell wafted to 'me by the breeze, that somebody is close to me.' "

Maui made known his presence and the old woman knew that he was a descendant of hers, and her stomach began immediately to shrink and contract itself again.

Then she asked, "Art thou Maui?"

He answered, "Even so," and told her that he wanted "the jaw-bone by which great enchantments could be wrought.”

Then Muri, the old chiefess, gave him the magic bone and he returned to his brothers, who were still living on the earth.

Then Maui said: "Let us now catch the sun in a noose that we may compel him to move more slowly in order that mankind may have long days to labor in and procure subsistence for themselves."

They replied, "No man can approach it on account of the fierceness of the heat."

According to the Society Island legend, his mother advised him to have nothing to do with the sun, who was a divine living creature, "in form like a man, possessed of fearful energy," shaking his golden locks both morning and evening in the eyes of men. Many persons had tried to regulate the movements of the sun, but had failed completely.

But Maui encouraged his mother and his brothers by asking them to remember his power to protect himself by the use of enchantments.

The Hawaiian legend says that Maui himself gathered cocoanut fibre in great quantity and manufactured it into strong ropes. But the legends of other islands say that he had the aid of his brothers, and while working learned many useful lessons. While winding and twisting they discovered how to make square ropes and flat ropes as well as the ordinary round rope. In the Society Islands, it is said, Maui and his brothers made six strong ropes of great length. These he called aeiariki (royal nooses).

The New Zealand legend says that when Maui and his brothers had finished making all the ropes required they took provisions and other things needed and journeyed toward the east to find the place where the sun should rise. Maui carried with him the magic jaw-bone which he had secured from Muri, his ancestress, in the under-world.

They travelled all night and concealed themselves by day so that the sun should not see them and become too suspicious and watchful. In this way they journeyed, until "at length they had gone very far to the eastward and had come to the very edge of the place out of which the sun rises. There they set to work and built on each side a long, high wall of clay, with huts of boughs of trees at each end to hide themselves in."

Here they laid a large noose made from their ropes and Maui concealed himself on one side of this place along which the sun must come, while his brothers hid on the other side.

Maui seized his magic enchanted jaw-bone as the weapon with which to fight the sun, and ordered his brothers to pull hard on the noose and not to be frightened or moved to set the sun free.

"At last the sun came rising up out of his place like a fire spreading far and wide over the mountains and forests.

He rises up.

His head passes through the noose.

The ropes are pulled tight.

Then the monster began to struggle and roll himself about, while the snare jerked backwards and forwards as he struggled. Ah! was not he held fast in the ropes of his enemies.

Then forth rushed that bold hero Maui with his enchanted weapon. The sun screamed aloud and roared. Maui struck him fiercely with many blows. They held him for a long time. At last they let him go, and then weak from wounds the sun crept very slowly and feebly along his course."

In this way the days were made longer so that men could perform their daily tasks and fruits and food plants could have time to grow.

The legend of the Hervey group of islands says that Maui made six snares and placed them at intervals along the path over which the sun must pass. The sun in the form of a man climbed up from Avaiki (Hawaiki). Maui pulled the first noose, but it slipped down the rising sun until it caught and was pulled tight around his feet.

Maui ran quickly to pull the ropes of the second snare, but that also slipped down, down, until it was tightened around the knees. Then Maui hastened to the third snare, while the sun was trying to rush along on his journey. The third snare caught around the hips. The fourth snare fastened itself around the waist. The fifth slipped under the arms, and yet the sun sped along as if but little inconvenienced by Maui's efforts.

Then Maui caught the last noose and threw it around the neck of the sun, and fastened the rope to a spur of rock. The sun struggled until nearly strangled to death and then gave up, promising Maui that he would go as slowly as was desired. Maui left the snares fastened to the sun to keep him in constant fear.

"These ropes may still be seen hanging from the sun at dawn and stretching into the skies when he descends into the ocean at night. By the assistance of these ropes he is gently let down into Ava-iki in the evening, and also raised up out of shadow-land in the morning."

Another legend from the Society Islands is related by Mr. Gill:

Maui tried many snares before he could catch the sun. The sun was the Hercules, or the Samson, of the heavens. He broke the strong cords of cocoanut fibre which Maui made and placed around the opening by which the sun climbed out from the under-world. Maui made stronger ropes, but still the sun broke them every one.

Then Maui thought of his sister's hair, the sister Inaika, whom he cruelly treated in later years. Her hair was long and beautiful. He cut off some of it and made a strong rope. With this he lassoed or rather snared the sun, and caught him around the throat. The sun quickly promised to be more thoughtful of the needs of men and go at a more reasonable pace across the sky.

A story from the American Indians is told in Hawaii's Young People, which is very similar to the Polynesian legends.