The Hawaiian

Archipelago:

Six months amongst the

palm groves, coral reefs, and volcanoes of the Sandwich Islands

By Isabella L. Bird, 1875

LETTER 18

|

Social Hurry—A Perfect Climate—Honolulu "Lions"—Queen Emma—A Royal Garden Party— Dwindling of the Native Population— Coinage and Newspapers

Hawaiian Hotel, Honolulu, March 20th

Oahu, with its grey pinnacles, deep valleys, cool chasms, ruddy headlands, and volcanic cones, all clothed in green by the recent rains, looked unspeakably lovely as we landed by sunrise in a rose-flushed atmosphere, and Honolulu, shady, dew-bathed, and brilliant with flowers, deserved its name, "The Paradise of the Pacific." The hotel is pleasant, and Mrs. D.'s presence makes it sweet and home-like; but in a very few days I have lost much of the health I gained on Hawaii, and the "Rolling Moses" and the Rocky Mountains can hardly come too soon. For Honolulu is truly a metropolis, gay, hospitable, and restless, and this hotel centralizes the restlessness. Visiting begins at breakfast time, when it ends I know not, and receiving and making visits, court festivities, entertainments given by the commissioners of the great powers, riding parties, picnics, verandah parties, "sociables," and luncheon and evening parties on board the ships of war, succeed each other with frightful rapidity. This is all on the surface, but beneath and better than this is a kindness which leaves no stranger to a sense of loneliness, no want uncared for, and no sorrow unalleviated. This, more than its beauty and its glorious climate, makes Honolulu "Paradise" for the many who arrive here sick and friendless. I notice that the people are very intimate with each other, and generally address each other by their Christian names. Very many are the descendants of the clerical and secular members of the mission, and these, besides being naturally intimate, are further drawn and held together by a society called "The Cousins' Society," the objects of which are admirable. The people take an intense interest in each other, and love each other unusually. Possibly they hate each other as cordially when occasion offers. It is a charming own, and the society is delightful. I wish I were well enough to enjoy it.

For people in the early stages of consumption this climate is perfect, owing to its equability, as also for bronchial affections. Unlike the health resorts of the Mediterranean, Algeria, Madeira, and Florida, where great summer heats or an unhealthy season compel half-cured invalids to depart in the spring, to return the next winter with fresh colds to begin the half-cure process again, people can live here until they are completely cured, as the climate is never unhealthy, and never too hot. Though the regular trades, which blow for nine months of the year, have not yet set in, and the mercury stands at 80°, there is no sultriness; a sea breeze and a mountain breeze fan the town, and the purple nights, when the stars hang out like lamps, and the moon gives a light which is almost golden, are cool and delicious. Roughly computed, the annual mean temperature is 75°, with a divergence in either direction of only 7°. As a general rule the temperature is cooler by four degrees for every thousand feet of altitude, so that people can choose their climate to suit themselves without leaving the islands.

I am gradually learning a little of the topography of this island and of Honolulu, but the last is very intricate. The appearance of Oahu from the sea is deceptive. It looks hardly larger than Arran, but it is really forty-six miles long by twenty-five broad, and is 530 square miles in extent. Diamond Hill, or Leahi, is the most prominent object south of the town, beyond the palm groves of Waikiki. It is red and arid, except when, as now, it is verdure-tinged by recent rains. Its height is 760 feet, and its crater nearly as deep, but its cone is rapidly diminishing. Some years ago, when the enormous quantity of thirty-six inches of rain fell in one week, the degradation of both exterior and interior was something incredible, and the same process is being carried on slowly or rapidly at all times. The Punchbowl, immediately behind Honolulu, is a crater of the same kind, but of yet more brilliant colouring: so red is V indeed, that one might suppose that its fires had just died out. In 1786 an observer noted it as being composed of high peaks; but atmospheric influences have reduced it to the appearance of a single wasting tufa cone, similar to those which stud the northern slopes of Mauna Kea. There are a number of shore craters on the island, and six groups of tufa cones, but from the disintegration of the lava, and the great depth of the soil in many places, it is supposed that volcanic action ceased earlier than on Maui or Hawaii. The shores are mostly fringed with coral reefs, often half a mile in width, composed of cemented coral fragments, shells, sand, and a growing species of zoophyte. The ancient reefs are elevated thirty, forty, and even too feet in some places, forming barriers which have changed lagoons into solid ground. Honolulu was a bay or lagoon, protected from the sea by a coral reef a mile wide; but the elevation of this reef twenty-five feet has furnished a site for the capital, by converting the bay into a low but beautifully situated plain.

The mountainous range behind is a rocky wall with outlying ridges, valleys of great size cutting the mountain to its core on either side, until the culminating peaks of Waiolani and Konahuanui, 4,000 feet above the sea, seem as if rent in twain to form the Nuuanu Valley. The windward side of this range is fertile, and is dotted over with rice and sugar plantations, but the leeward side has not a trace of the redundancy of the tropics, and this very barrenness gives a unique charm to the exotic beauty of Honolulu.

It is daily a fresh pleasure to stroll along the shady streets and revel among palms and bananas, to see clusters of the granadilla and night-blowing Cereus mixed with the double blue pea, tumbling over walls and fences, while the vermilion flowers of the Ponciana Regia, like spikes of red coral, and the flaring magenta Bougainvillea (which is not a flower at all, but an audacious freak of terminal leaves) light up the shade, and the purple-leaved Dracaena which we grow in pots for dinner-table ornament, is as common as a weed.

Besides this hotel, and the handsome but exaggerated and inappropriate Government buildings not yet finished, there are few "imposing edifices" here. The tasteful but temporary English Cathedral, the Kaiwaiaho Church, diminished once to suit a dwindled population, but already too large again; the prison, a clean, roomy building, empty in the daytime, because the convicts are sent out to labour on roads and public works; the Queen's Hospital for Curables, for which Queen Emma and her husband became mendicants in Honolulu; the Court House, a staring, unshaded building; and the Iolani Palace, almost exhaust the category. Of this last, little can be said, except that it is appropriate and proportioned to a kingdom of 56,000 souls, which is more than can be said of the income of the kmg, the salaries of the ministers, and some other things. It stands in pleasure-grounds of about an acre in extent, with a fine avenue running through them, and is approached by a flight of steps which leads to a tolerably spacious hall, decorated in the European style. Portraits of Louis Philippe and his queen, presented by themselves, and of the late Admiral Thomas, adorn the walls. The Hawaiians have a profound aspect for this officer's memory, as it was through him that the sovereignty of the islands was promptly restored to the native rulers, after the infamous affair of its cession to England, as represented by Lord George Paulet. There are also some ornamental vases and miniature copies of some of Thorwaldsen's works. The throne-room takes up the left wing of the palace. This unfortunately resembles a rather dreary drawing-room in London or New York, and has no distinctive features except a decorated chair, which is the Hawaiian throne. There is an Hawaiian crown also, neither grand nor costly, but this I have not seen. At present the palace is only used for state receptions and entertainments, for the king is living at his private residence of Haemoeipio, not far off.

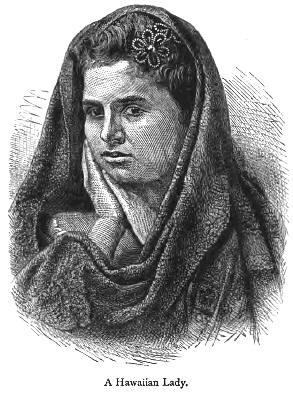

Miss W. kindly introduced me to Queen Emma, or Kaleleonalani, the widowed queen of Kamehameha IV., whom you will remember as having visited England a few years ago, when she received great attention. She has one-fourth of English blood in her veins, but her complexion is fully as dark as if she were of unmixed Hawaiian descent, and her features, though refined by education and circumstances, are also Hawaiian; but she is a very pretty, as well as a very graceful woman. She was brought up by Dr. Rooke, an English physician here, and though educated at the American school for the children of chiefs, is very English in her leanings and sympathies, an attached member of the English Church, and an ardent supporter of the "Honolulu Mission." Socially she is very popular, and her exceeding kindness and benevolence, with her strongly national feeling as an Hawaiian, make her much beloved by the natives.

The winter palace, as her town house is called, is a large, shady abode, like an old-fashioned New England house externally, but with two deep verandahs, and the entrance is on the upper one. The lower floor seemed given up to attendants and offices, and a native woman was ironing clothes under a tree. Upstairs, the house is like a tasteful, English country house, with a pleasant English look, as if its furniture and ornaments had been gradually accumulating during a series of years, and possessed individual histories and reminiscences, rather than as if they had been ordered together as "plenishings" from stores. Indeed, it is the most English-looking house I have seen since I left home, except Bishops court at Melbourne. If there were a bell I did not see it; and we did not ring, for the queen received us at the door of the drawing-room, which was open. I had seen her before in European dress, driving a pair of showy black horses in a stylish English phaeton; but on this occasion she was not receiving visitors formally, and was indulging in wearing the native holoku, and her black wavy hair was left to its own devices. She is rather below the middle height, very young-looking for her age, which is thirty-seven, and very graceful in her movements. Her manner is indeed very fascinating from a combination of unconscious dignity with ladylike simplicity. Her expression is sweet and gentle, with the same look of sadness about her eyes that the king has, but she has a brightness and archness of expression which give a great charm to her appearance. She has sorrowed much: first, for the death, at the age of four, of her only child, the Prince of Hawaii, who when dying was baptized into the English Church by the name of Albert Edward, Queen Victoria and the Prince of Wales being his sponsors; and secondly, for the premature death of her husband, to whom she was much attached. She speaks English beautifully, only hesitating, now and then for the most correct form of expression. She spoke a good deal and with great pleasure of England; and described Venice and the emotions it excited in her so admirably, that I should like to have heard her describe all Europe.

A few days afterwards I went to a garden party at her house. It was a very pretty sight, and the "everybody" of Honolulu was there to the number of 250. I must describe it for the benefit of , who persists in thinking that coloured royalty must necessarily be grotesque. People arrived shortly before sunset, and was received by Queen Emma, who sat on the lawn, with her attendants about her, very simply dressed in black silk. The king, at whose entrance the band played the national anthem, stood on another lawn, where presentations were made by the chamberlain; and those who were already acquainted with him had an opportunity for a few minutes' conversation. He was dressed in a well-made black morning suit, and wore the ribbon and star of the Austrian order of Francis Joseph. His simplicity was atoned for by the superlative splendour of his suite; the governor of Oahu, and the high chief Kalakaua, who was a rival candidate for the throne, being conspicuously resplendent. The basis of the costume appeared to be the Windsor uniform, but it was smothered with epaulettes, cordons, and lace; and each dignitary has a uniform peculiar to his office, so that the display of gold lace was prodigious. The chiefs are so raised above the common people in height, size, and general nobility of aspect, that many have supposed them to be of a different race; and the alii who represented the dwindled order that night were certainly superb enough in appearance to justify the supposition. Beside their splendour and stateliness, the forty officers of the English and American war-ships, though all in full-dress uniform, looked decidedly insignificant; and I doubt not that the natives who were assembled outside the garden railings in crowds were not behind me in making invidious comparisons.

Chairs and benches were placed under the beautiful trees, and people grouped themselves on these, and promenaded, flirted, talked politics and gossip, or listened to the royal band, which played at intervals, and played well. The dress of the ladies, whether white or coloured, was both pretty and appropriate. Most of the younger women were in white, and wore natural flowers in their hair; and many of the elder ladies wore black or coloured silks, with lace and trains. There were several beautiful leis of the gardenia, which filled all the garden with their delicious odour. Tea and ices were handed round on Sevres china by footmen and pages in appropriate liveries. What a wonderful leap from calabashes and poi, malos and paus, to this correct and tasteful civilization! As soon as the brief, amber twilight of the tropics was over, the garden was suddenly illuminated by myriads of Chinese lanterns, and the effect was bewitching. The upper suite of rooms was thrown open for those who preferred dancing under cover j but I think that the greater part of the assemblage chose the shady walks and purple night. Supper was served at eleven, and the party broke up soon afterwards; but I must confess that, charming as it was, I left before eight, for society makes heavier demands on my strength than the rough, open-air life of Hawaii.

The dwindling of the race is a most pathetic subject. Here is a sovereign chosen amidst an outburst of popular enthusiasm, with a cabinet, a legislature, and a costly and elaborate governing machinery, sufficient in Yankee phrase to "run" an empire of several millions, and here are only 49,000 native Hawaiians; and if the decrease be not arrested, in a quarter of a century there will not be an Hawaiian to govern. The chiefs, or alii, are a nearly extinct order; and, with a few exceptions, those who remain are childless. In riding through Hawaii I came everywhere upon traces of a once numerous population, where the hill slopes are now only a wilderness of guava scrub, and upon churches and school-houses all too large, while in some hamlets the voices of young children were altogether wanting. This nation, with its elaborate governmental machinery, its churches and institutions, has to me the mournful aspect of a shrivelled and wizened old man dressed in clothing much too big, the garments of his once athletic and vigorous youth. Nor can I divest myself of the idea that the laughing, flower-clad hordes of riders who make the town gay with their presence, are but like butterflies fluttering out their short lives in the sunshine.

The statistics on this subject are perfectly appalling. If we reduce Captain Cook's estimate of the native population by one-fourth it was 300,000 in 1779. In 1872 it was only 49,000. The first official census was in 1832, when the native population was 130,000. This makes the decrease 80,000 in forty years, or at the rate of 2,000 a year, and fixes the period for the final extinction of the race in 1897, if that rate were to continue. It is a pity, for many reasons, that it is dying out. It has shown a singular aptitude for politics and civilization, and it would have been interesting to watch the development of a strictly Polynesian monarchy starting under passably fair conditions. Whites have conveyed to these shores slow but infallible destruction on the one hand, and on the other the knowledge of the life that is to come; and the rival influences of blessing and cursing have now been fifty years at work, producing results with which most reading people are familiar.

I have not heard the subject spoken of, but I should think that the decrease in the population must cause the burden of taxation to press heavily on that which remains. Kings, cabinet ministers, an army, a police, a national debt, a supreme court, and common schools, are costly luxuries or necessaries. The civil list is ludicrously out of proportion to the resources of the islands, and the heads of the four departments—Foreign Relations, Interior, Finance, and Law (Attorney-General)— receive $5,000 a year each!

Expenses and salaries have been increasing for the last thirty years. For schools alone every man between twenty-one and sixty pays a tax of two dollars annually, and there is an additional general tax for the same purpose. I suppose that there is not a better educated country in the world. Education is compulsory; and besides the primary schools, there are a number of academies, all under Government supervision, and there are 324 teachers, or one for every twenty-seven children. There is a Board of Education, and Kamakau, its president, reported to the last biennial session of the legislature that out of 8931 children between the ages of six and fifteen, 8287 were actually attending school! Among other direct taxes, every quadruped that can be called ft horse, above two years old, pays a dollar a year, and every dog a dollar and a half. Does not all this sound painfully civilized? If the influence of the tropics has betrayed me into rhapsody and ecstacy in earlier letters, these dry details will turn the scale in favour of prosaic sobriety!

I have said little about Honolulu, except of its tropical beauty. It does not look as if it had "seen better days." Its wharves are well cared for, and its streets and roads are very clean. The retail stores are generally to be found in two long streets which run inland, and in a splay street which crosses both. The upper storekeepers, with a few exceptions, are Americans, but one street is nearly given up to Chinamen's stores, and one of the wealthiest and most honourable merchants in the town is a Chinaman. There is an ice factory, and ice cream is included in the daily bill of fare here, and iced water is supplied without limit, but lately the machinery has only worked in spasms, and the absence of ice is regarded as a local calamity, though the water supplied from the waterworks is both cool and pure. There are two good photographers and two booksellers. I don't think that plate glass fronts are yet to be seen. Many of the storekeepers employ native "assistants;" but the natives show little aptitude for mercantile affairs, or indeed for the "splendid science” of money-making generally, and in this respect contrast with the Chinamen, who, having come here as coolies, have contrived to secure a large share of the small traffic of the islands. Most things are expensive, but they are good. I have seen little of such decided rubbish as is to be found in the cheap stores of London and Edinburgh, except in tawdry artificial flowers. Good black silks are to be bought, and are as essential to the equipment of a lady as at home. Saddles are to be had at most of the stores, from the elaborate Mexican and Californian saddle, worth from 30 to 50 dollars, to a worthless imitation of the English saddle, dear at five. Boots and shoes, perhaps because in this climate they are a mere luxury, are frightfully dear, and so are books, writing paper, and stationery generally; a sheet of Bristol board, which we buy at home for 6d. y being half a dollar here. But it is quite a pleasure to make purchases in the stores. There is so much cordiality and courtesy that, as at this hotel, the bill recedes into the background, and the purchaser feels the indebted party.

The money is extremely puzzling. These islands, like California, have repudiated greenbacks, and the only paper currency is a small number of treasury notes for large amounts. The coin in circulation is gold and silver, but gold is scarce, which is an inconvenience to people who have to carry a large amount of money about with them. The coinage is nominally that of the United States, but the dollars are Mexican, or French 5 franc pieces, and people speak of "rials" which have no existence here, and of "bits," a Californian slang term for 12 1/2 cents, a coin which to my knowledge does not exist anywhere. A dime, or 10 cents, is the lowest coin I have seen, and copper is not in circulation. An envelope, a penny bottle of ink, a pencil, a spool of thread, cost 10 cents each; postage-stamps cost 2 cents each for inter-island postage, but one must buy five of them, and dimes slip away quickly and imperceptibly. There is a loss on English money, as half-a-crown only passes for a half-dollar, sixpence for a dime, and so forth; indeed, the average loss seems to be about two pence in the shilling.

There are four newspapers: the Honolulu Gazette, the Pacific Commercial Advertiser, Ka Nupepa Kuokoa (the Independent Press), and a lately started spasmodic sheet, partly in English and partly in Hawaiian, the Nuhou (News). The two first are moral and respectable, but indulge in the American sins of personalities and mutual vituperation. The Nuhou is scurrilous and diverting, and appears "run" with a special object, which I have not as yet succeeded in unravelling from its pungent but not always intelligible pages. I think perhaps the writing in each paper has something of the American tendency to hysteria and convulsions, though these maladies are mild as compared with the "real thing" in the Alta California, which is largely taken here. Besides these there are monthly sheets called The Friend, the oldest paper in the Pacific, edited by good "Father Damon," and the Church Messenger, edited by Bishop Willis, partly devotional and partly devoted to the Honolulu Mission. All our popular American and English literature is read here, and I have hardly seen a table without "Scribner's" or "Harper's Monthly," or "Good Words."

I have lived far too much in America to feel myself a stranger where, as here, American influence and customs are dominant; but the English who are in Honolulu just now, in transitu from New Zealand, complain bitterly of its "Yankeeism," and are very far from being at home, and I doubt not that Mr. M , whom you will see, will not confirm my favourable description. It is quite true that the islands are Americanized, and with the exception of the Finance Minister, who is a Scotchman, Americans "run" the Government and fill the Chief Justiceship and other high offices of State. It is, however, perfectly fair, for Americans have civilized and Christianized Hawaii-nei, and we have done little except make an unjust and afterwards disavowed seizure of the islands.

On looking over this letter I find it an olla podrida of tropical glories, royal festivities, finance matters, and odds and ends in general. I dare say you will find it dull after my letters from Hawaii, but there are others who will prefer its prosaic details to Kilauea and Waimanu; and I confess that, amidst the general lusciousness of tropical life, I myself enjoy the dryness and tartness of statistics, and hard, uncoloured facts. I.L.B |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |