A

Cultural History of Three

Traditional Hawaiian Sites

on the

West Coast of Hawai'i Island

Overview of Hawaiian History

by Diane Lee Rhodes

(with some additions by Linda Wedel Greene)

|

Chapter 6: Development and Human

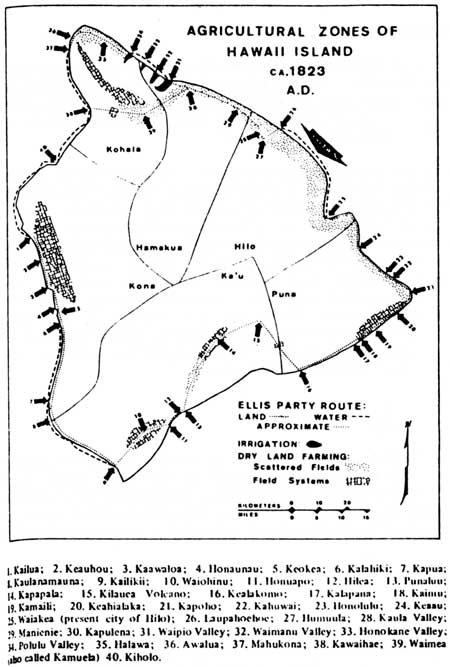

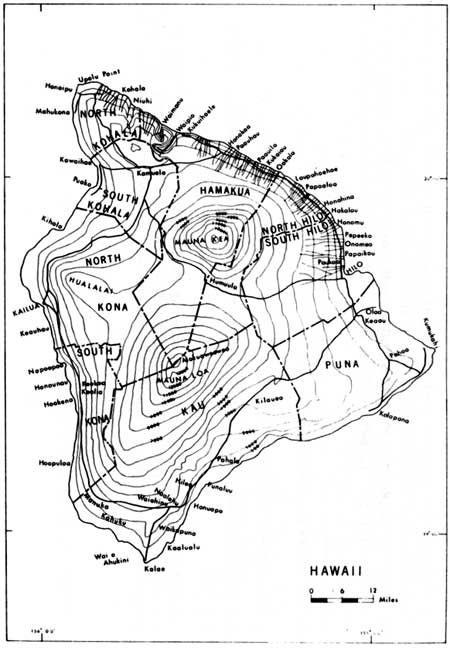

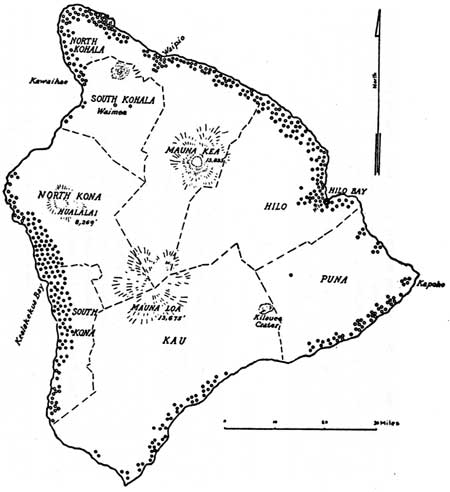

Activity on the West Coast of the Island of Hawai`i A. Population The island of Hawai'i lies at the southeastern end of the Hawaiian archipelago. Located about 148 miles southeast of Honolulu, it owes its existence to the actions of five volcanoes Kohala, Mauna Kea, Hualalai, Mauna Loa, and Kilauea (actually a caldera on Mauna Loa). The island is 76 miles wide, 93 miles long, and has an area of 4,030 square miles, with its highest point the top of Mauna Kea, 13,784 feet above sea level. Exact historical figures are uncertain, but at the time of the arrival of Capt. James Cook in 1778, the population of Hawai'i Island was estimated at about 120,000. The most continuously and densely populated area stretched along the coasts of North and South Kona; that population was estimated at about 20,000 individuals. The Reverend William Ellis, who circled the entire island in 1823, recommended the establishment of missionary stations at Kailua, Kealakekua, and Honaunau because of their density (Illustration 21). Possibly some Europeans other than missionaries lived along the west coast of Hawai'i Island by 1825, but there is no mention of them in the literature. Most Europeans living in the islands were tradesmen working for the king, who stayed in close proximity to him in Honolulu. Although Ellis believed that Hawai'i supported a larger population than the rest of the islands, he observed that Honolulu was regarded as the chief port for foreign trade as well as the home base of the missionaries and that the king and major chiefs were already forsaking Hawai'i for O'ahu.

B. Water Resources In very general terms, West Hawai'i comprises the leeward side of the island, extending from 'Upolu Point on the north to Ka Lae at the southern tip. The rugged volcanic masses of Kohala, Mauna Kea, Hualalai, and Mauna Loa separate this region from the wetter, windward side of the island to the east. Because it seldom rains on the leeward coast, West Hawai'i is characterized by a paucity of stream drainages and a tendency to aridity any loose water is quickly absorbed in the porous earth. The Reverend William Ellis observed this water problem, finding on his journey that

Missionary Henry Cheever noted wryly that "On that part [leeward coast] of the great Island of Hawaii there is not a brook that runs into the sea for more than a hundred miles of coast. At Kealakekua ships can hardly get a cask of genuine fresh water for fear, love, or money." He noted that Captain Cook had to acquire his supply from natives who brought it in calabashes from the mountains, four miles away. Missionary stations, he said, had to be supplied in the same manner. The natives, however, could drink from the brackish springs on the coast, "the water of which is almost as nauseous and purgative, with a stranger, as a dose of salts." C. Volcanic Activity Both North and South Kona show traces of prehistoric and historic lava flows. Cheever described the area from Kealakekua toward the south and middle sections of the island as containing frequent traces of recent volcanic activity. Whether coasting along in a canoe or traveling on foot ashore, he stated, one passed "rugged cones and oven-like blisters, deep-mouthed caves and fissures, enormous gaps and ravines, overhanging arches and natural bridges, great tunnels and blow-holes." Archeological data, however, suggests that the people adjusted well to the topographical changes caused by these eruptions, and today one can find trails and other features constructed on top of the 1859 Mauna Loa flow and the Hualalai flows of 1800-1. Hualalai has not erupted since early historic times (1801), but the land has been subjected to repeated eruptions from Mauna Loa into the historic period. The earliest volcanic outbreak described historically issued in November 1790 from the caldera of Kilauea on a flank of Mauna Loa. Earthquake shocks accompanied the violent eruption, which included the ejection of large quantities of stone and cinders. This hot base surge composed primarily of superheated steam suffocated soldiers in the army of Keoua, the rival of Kamehameha. In 1801 an eruption from the west side of dormant Hualalai occurred the first one in the Hawaiian Islands witnessed by Europeans. Lava flowed rapidly to the sea six miles away, covering villages, agricultural plots, and fish ponds. Other eruptions from Mauna Loa occurred in 1823,1832,1840, and 1843. In 1859 two lava streams poured forth from new craters on the north slope of Mauna Loa. Eight days later, the lava began flowing into the sea at a village about fourteen miles from Kawaihae in the Kohala District. This activity continued for three weeks. A worse disaster occurred in 1868 when Mauna Loa erupted, precipitating severe earthquakes and an eruption of mud that extended for three miles, varying from one-half to one mile wide and from two to thirty feet deep. The mudslide swept away houses and stock and took a number of lives. It was followed by an enormous tidal wave that battered the coast, further destroying lives and property. The abundance of rocks remaining from volcanic activity during prehistoric and historic times supplied the inhabitants of the west coast with building material for house platforms, temples, fences, and agricultural and stock enclosures. (The latter were more common after the introduction of grazing animals by Westerners.) The many crevices and caves created by the numerous lava flows provided both habitation sites and burial places. D. Political History Initial settlement on the island of Hawai'i probably occurred in its windward valleys by A.D. 300 to 500, with the population slowly moving to suitable, less-crowded sites on the leeward coast over the next few hundred years. (South Point [Ka Lae], however, has one of the earliest Carbon 14 dates in the islands.) Ancient land districts on the island of Hawai'i consisted of Puna, Hilo, Hamakua, Kohala, Kona, and Ka'u, which were traditionally autonomous chiefdoms. By the 1400s, dual seats of power existed on the windward and leeward coasts. The "Kona" chiefs governed Kohala, Kona, and Ka'u, while the "I" chiefs controlled Hamakua, Hilo, and Puna. The first chief to unite the island of Hawai'i was 'Umi-a-Liloa, whose father had been "supreme" ruler of the island with his court located in Waipi'o Valley, Hamakua. 'Umi subsequently moved the seat of power from the windward to the leeward side of the island at Kona. All this probably took place sometime during the early 1400s to the early 1600s. 'Umi reportedly established the principle of division of labor among his people, designating specialists in various crafts as well as in professions such as government and land administration, religion, and industry. Possibly he instituted this system in response to the increasing population and a need to increase work efficiency and resource utilization. The economic and social problems inherent in swift population growth continued, however, and kept the political situation unsettled long after 'Umi's death. Tradition implies that the period from 1500 to the mid-1700s consisted of continual attempts to wrest power from 'Umi's descendants. These cycles of conquest and re-conquest finally ended with Kamehameha's unification of the Hawaiian Islands in the early Western contact period. The earlier chiefdoms evolved into the six districts of Kamehameha's kingdom. Despite the further subdivision of Hilo, Kohala, and Kona into northern and southern portions, the original district boundaries of Hawai'i Island exist today, probably due to their natural separation by certain physical barriers. E. Settlement Patterns A variety of ethnographic materials exist for West Hawai'i, primarily because it was the ancestral seat of a powerful line of hereditary chiefs, including Kamehameha, and because many Europeans who left behind journals and logs investigated the Kona and Kohala districts in the late 1700s and the 1800s as they paid their respects to the ruling power in the islands. Sea captain George Dixon, for instance, master of the Queen Charlotte, described the country next to the sea in West Hawai'i as crowded with villages protected from the scorching heat by the spreading branches of coco palm and mulberry trees. He noted cracks and crevices along the coast filled with humus and sown with vegetables and other plants. As did many other observers, he mentioned the large lava tubes that formed caves along the coast, many of which were used for habitation or for refuge. Factors such as terrain and climate determined settlement patterns on the west coast of Hawai'i. As Dixon noted, most of the population chose to live in small villages on non-agricultural land near the shore or clustered around bays where the air was warm and dry. Fish and marine resources were nearby and plentiful. These coastal dwellers also cultivated the moist uplands, which they reached by trails several miles long. The seaward slope became a mixed agricultural zone, with breadfruit planted on the lower slopes and large sweet potato and dry land taro plantations established in the higher elevations that received more rain. With the demise of the breadfruit plantations, small fields of crops were planted in those areas and enclosed with low stone walls concealed by sugarcane. Plantains and bananas were sometimes planted in the lower reaches of the rain forest. Upland forests contained a small number of people, in temporary villages, who hunted birds, harvested timber and bark, and logged sandalwood. Fish and other marine resources from the coast, plus crops and wild plants harvested from the higher slopes, supplied all the food, shelter, and clothing needs of people on the west coast of Hawai'i.

F. Subsistence Patterns Intensive agricultural activity comprised an important aspect of life on the western side of Hawai'i Island; the Kona and Kohala field systems were in use before European contact. The Kona field system was quite large, extending from Kailua to south of Honaunau. The Kohala field system stretched along the west flanks of Kohala Mountain. Both are "patterned networks of elongated rectangles lying as a band parallel to the coastline." Earth and rock ridges built to enclose the fields cause the patterning effect. The fields behind Kona consisted of four agricultural zones: sweet potatoes and paper mulberry planted just above sea level grew well but not abundantly; breadfruit trees, sweet potatoes, and paper mulberry did well in the area above that, while sweet potatoes and dryland taro were cultivated in the next higher zone; plantains and bananas grew on the heights. The rectangular fields characterize the two central zones. The raised borders of the fields supported sugarcane and ti. The Kohala field system was probably about the same, though we have few descriptions, but without the breadfruit trees. Studies of the Kohala area have disclosed a complex system of cultural features, including dwelling and salt manufacturing sites along the coast, and agricultural features comprising rock cairns possibly used for growing specialized crops such as gourds. In addition, rocky, asymmetrical garden areas possibly housed taller plants such as bananas, while exclosures of stacked rock of various shapes kept animals from crops and prevented wind damage. G. Kona District 1. Pre-European Contact Period The Kona District, significant in Hawai'i's development during both prehistoric and historic times, includes most of the western coast of the island of Hawai'i. Dormant Hualalai volcano towers above the shoreline in North Kona, while South Kona includes the still-active Mauna Loa. The Kona Coast is covered with barren lava flows broken only occasionally by fertile patches of land. These successive streams of lava, which have cascaded over the cliffs into the sea and then solidified, contain numerous caves. The coast's warm, dry climate and fertility made it a favorite residential area of Hawai'i's chiefs. And wherever the ruling chief had his home, a large group of houses for the commoners and members of the royal entourage could also be found. Because the high chiefs of Kona lived at Kailua, it became a thriving settlement. As mentioned, when foreign visitation began, the Kona District was probably the most densely populated area in the Hawaiian Islands. Many ancient traditions and mythological personnages were associated with Kona, such as the god Lono, who supposedly introduced the primary plant foods such as taro, sweet potato, yams, sugarcane, and bananas to the Hawaiians. In addition, the Makahiki festival and other rituals for invoking rain and fertility centered in Kona, 2. European Contact Period The death in 1782 of the chief of Hawai'i, Kalani'opu'u, who had greeted Captain Cook at Kealakekua Bay, left his son Kiwala'o and his nephew Kamehameha in competition for control of the western half of the island. The battle of Moku'ohai in Kona decided the contest for Kamehameha, who then had to fight his cousin Keoua for control of the entire island in 1791. Kamehameha finally became chief of Hawai'i Island after the death of Keoua at Kawaihae. Four years later Kamehameha conquered Maui, Moloka'i, Lana'i, and O'ahu, and ultimately received Kaua'i by cession in 1810. The changing political situation and the growth of international trade in the years following Cook's arrival somewhat changed the status of the Kona Coast in terms of its political and social role in Hawaiian life. As stability gradually returned to political affairs, the king and his chiefs began concentrating more on interaction with trading and whaling vessels and foreign emissaries, which was easier in the better harbors of Honolulu (O'ahu) and Lahaina (Maui). In addition, with the overthrow of the ancient kapu system in 1819, the Hawaiian people as a whole, and their government, began a course of rapid change. Although deregulation and lack of guidance characterized most of Hawaiian society at that time, the Kona Coast remained relatively stable, socially and economically, from the 1820s to about 1852, despite the fact it had been the scene of the kapu abolition. Several factors contributed to this condition: first, King Kamehameha II and his court moved their place of residence to Honolulu shortly after the abolition; second, the many chiefs who continued to live along the coast near Kailua provided some leadership for the population there, which resulted in continuous immigration from other districts by people seeking the security offered by the presence of these chiefs and the pleasures and amenities of urban life stimulated by the presence of a continuing throng of foreign visitors; third, the agricultural importance of the area, which possessed two good harbors and a productive inland region, and the influx of trading and whaling ships seeking fruit, vegetables, and meat in addition to firewood and fresh water, provided an impetus for the continuation of planting and harvesting despite the lack of the former religious cycles; and fourth, the arrival of the missionaries at Kailua and the spread of their teachings provided a steadying influence on Kona Coast society. 3. North and South Kona a) Historical Descriptions The Kona District comprises two subdivisions, North and South Kona. The first stretches from just north of Kealakekua Bay to 'Anaeho'omalu, while the second includes the lands from the bay south to Kamoi Point. In 1823 the Reverend Ellis described Kona as

Traveling along the coast, Ellis

William Bryan also commented on the numerous stone heiau worthy of notice along the Kona Coast. He observed that these temples, usually located near the shore, were numerous in densely populated regions on all the islands; on Hawai'i, however, the region between Kailua and Kealakekua had a particularly heavy concentration of them. Early explorers, traders, and visitors described some of the temples around Kailua, while investigation by a variety of scholars has turned up the sites of many others. Notable among the Kona heiau are Hikiau, the temple at Kealakekua Bay where Captain Cook was worshipped as the god Lono, and 'Ahu'ena, adjacent to Kamehameha I's royal residence at Kailua. Hale-o-Keawe, the ancestral heiau and mausoleum of the Kamehameha dynasty, is located in Pu'uhonua o Honaunau National Historical Park. Commodore Charles Wilkes of the 1838-42 U.S. Exploring Expedition states that the inhabitants of the Kona Coast in 1840 planted sweet potatoes, melons, and pineapples among the lava rocks during the rainy season. Staple foods there consisted of sweet potatoes and upland taro, while yams were raised to supply ships in port. People also cultivated sugarcane, bananas, breadfruit, and coconuts. Irish potatoes, Indian corn, beans, coffee, cotton, figs, oranges, and grapes had been introduced from the West but were not grown in any quantity. Breadfruit grew two miles inland, and taro above that. A lively trade flourished between the southern and northern ends of the district, with those residing in the less fertile northern portion bartering fish and manufactured salt for food and clothing from the south. b) Settlement Patterns Archeologist Paul Rosendahl states that most of the ethnohistorical data pertaining to North Kona available today references the lands between Kailua and Honaunau. North of Kailua-Kona, inland to Napu'u and along the coast to 'Anaeho'omalu, lies an area of broad lava fields called Kekaha, a word that describes a dry, sunbaked land. This area is veined with both recent (1800-1, 1859) and ancient rugged lava flows that restrict foot travel to laboriously built trails. Because travel north between Kailua and the important port of Kawaihae in the Kohala District appears to have been mainly by canoe rather than along these coastal trails during both the prehistoric and historic periods, there are few descriptions available of this northern coast area. However, some assumptions can be made concerning settlement patterns in the area between Kailua and 'Anaeho'omalu. According to Rosendahl, ancient occupation of North Kona took place in three main zones: the narrow, arid coastal strip; the sloping, barren middle zone composed of volcanic materials; and the upland zone utilized for agricultural purposes. The probable pattern of aboriginal settlement between Kailua and Anaehoomalu consisted of small fishing hamlets located along the shore, often near fishponds and around bays. Their inhabitants were involved in deep-water and in-shore fishing and the gathering of other marine resources. In addition, they produced salt and raised fish in ponds. Agricultural pursuits involved only small coconut groves planted around villages and fishponds and limited raising of sweet potatoes and bananas in small, sandy beach areas and in whatever tiny patches of soil could be found on the surface of the lava flows. More people lived in scattered hamlets in the uplands, where they extensively cultivated dryland taro and sweet potatoes. Other crops included breadfruit, bananas, paper mulberry, ti, and sugarcane. The middle barren zone, Rosendahl suggests, supported temporary use by travellers between the uplands and the coast. In addition, natural caves in the zone might have been used as residences by those engaged in longer-term marine exploitation activities or other specialized pursuits such as hunting. They might also have been utilized for refuge or as burial sites. Devastating measles, whooping cough, diarrhea, and flu epidemics in the mid-nineteenth century drastically affected the population of North Kona. South Kona exhibits the same three types of habitation zones: coastal (maritime activity, limited agriculture); transitional, or middle (temporary habitation); and inland (large-scale agriculture). Early visitors to the islands frequently mentioned the coastal area south of Kealakekua Bay down to Honaunau. Members of Capt. James Cook's expedition mentioned sweet potatoes growing in small enclosures protected by low stone walls and additional cultivation of sugarcane, bananas, and breadfruit trees. Archibald Menzies, visiting the area between 1792 and 1794 with Capt. George Vancouver, described the stretch of coastline south of Kealakekua Bay as "a dreary naked barren waste" broken only by a few coconut groves near the villages. He noted, however, small fields higher up on the plains near the woods that were heavily cultivated with taro and ti. The Reverend William Ellis commented that about two miles inland from Honaunau, population was dense and fields well cultivated. All these accounts seem to agree that the mauka (toward the mountains) lands were primarily agricultural and heavily occupied. A trail system linked the coast and the uplands. One author states that land utilization in this area "had to be efficient enough to support the many high chiefs, their retainers, priests and craftsmen who resided at Kaawaloa, Napoopoo, Ke'ei and Honaunau at the time of Cook's arrival." c) Towns and Sites The town of Kailua, Kona, is one of the most historically significant areas in Hawai'i. Long the residence of Hawaiian chiefs, it is also the site of Kamakahonu, the parcel of land containing King Kamehameha's principal residence and court. This was the king's home during the last years of his life; this is where, following his death, his successor Liholiho overthrew the kapu system. And this is the point where the missionaries landed, pleased to find that their work of abolishing the old religion had been accomplished for them. Kamehameha returned here in 1812 from Honolulu, O'ahu, where he had spent the previous few years, accompanied by his family and a vast array of chiefs and retainers. This area has been described in great detail by visitors and explorers to the island who stopped here to pay their respects to the Hawaiian ruler. The Reverend William Ellis described Kailua in 1823:

Honaunau, a land division south of Kailua, is another very famous spot, containing within its boundaries a place of refuge, and Hale-o-Keawe, where twenty-three of Kamehameha's family were interred, including a son. William Bryan also visited that site; by the time he saw it, a portion of the structure, which occupied six or seven acres of a low, rocky point on the south side of the bay, had been destroyed some years previously by tidal waves. At Kealakekua Bay, another famous locale in South Kona, Bryan noted the monument to Captain Cook. That harbor supported two settlements Ka'awaloa on the north side, the scene of Captain Cook's death, and Kealakekua (Napo'opo'o) on the south. The cliffs above Ka'awaloa contain numerous burial caves. Hikiau Heiau, on which Cook established his observatories, is on the shore of Kealakekua Bay. These were good-sized settlements, Kealakekua containing more than one thousand structures by the late 1700s. Kalani'opu'u, king of Hawai'i Island at the time of Cook's arrival, lived in this area. In ancient times, local chiefs travelled along the coasts by canoe and established temporary residences at certain sites for purposes of business or pleasure. Kealakekua Bay supported many temporary shelters erected by the residents for visiting chiefs. Temporary structures were also needed for storage of utensils and tools, for shelter during rains, and for security during kapu periods. Additional shelters were also needed by those attracted to the village by the presence of foreign ships and by those serving the high chiefs and their foreign guests. Thus both Ka'awaloa and Napo'opo'o by 1779 held not only permanent structures for the king and those who came to visit or to serve him, but also temporary complexes for visiting chiefs and structures for their supporters. After the government moved to Honolulu, it sent monthly vessels to the ports of Kailua and Kealakekua Bay to acquire the produce of their upland fields. According to Anthropologist Dorothy Barr่re, most foreign ships arriving at Hawai'i Island moored in the better-protected Kealakekua Bay. Only a few traders and whalers anchored at Kawaihae in Kohala or at Kailua. Wherever they landed, however, all captains had to obtain Kamehameha's permission to supply or refit their ships. H. Kohala District 1. Pre-European Contact Period The Kohala District comprises the northernmost land area of the island of Hawai'i. It is important for many reasons, not the least of which is that it was the birthplace and ancestral chiefdom of Kamehameha, born about 1753 near Mo'okini temple at Kokoiki, 'Upolu Point. Mo'okini Heiau is one of the most famous and best preserved temples in Hawai'i, traditionally reported to have been built by the Polynesian priest Pa'ao. The areas of Kawaihae and Waimea were the site of continual battles between the armies of the six kingdoms of the island to enlarge their domains. In addition, fleets from Maui that had fought in Kona, returning home, would land at various places along the Kohala coast to wreak havoc, often cutting down the coconut trees at Kawaihae as a show of defiance to the island chiefs. The ancient temple of Mailekini at Kawaihae was a prize held by the South Kohala chief. 2. European Contact Period The largest coastal town is Kawaihae, which lies on a broad, shallow bay. It has always served as the district's primary seaport the most convenient point of embarkation for inhabitants of the northern part of the island and of debarkation for mail and visitors to this district, as well as the place from which to ship surplus goods from the hinterland to market. In ancient times it was a good-sized fishing village. The land surrounding it is semi-arid and barren and struck many early visitors as somewhat unattractive. George Washington Bates, visiting Hawai'i in 1853, noted:

Despite its unimpressive appearance to most outsiders, Kawaihae's importance in ancient Hawaiian history is indisputable. It is the site of Pu'ukohola Heiau, the most significant historical structure associated with Kamehameha I's rise to power. Upon its altar Kamehameha sacrificed his rival Keoua and some of his followers to ensure his unchallenged rule over the island. The area also served as a periodic residence of Hawaiian royalty over the years. In 1793 Captain George Vancouver, on his way to Kealakekua Bay to deliver the first cattle to Hawai'i, stopped in Kawaihae Bay to release the weakest pair of animals, which he was certain would not last the journey farther down the coast. Ten years later Captain Richard J. Cleveland stopped here with the first horses to be delivered to the king, causing "incessant exclamations of astonishment." The town also had four famous salt ponds, which will be described in more detail later. The missionary brig Thaddeus anchored offshore of Kawaihae in 1820, its occupants learning to their astonishment of the overthrow of the kapu system and gaining their first look at their new home. 3. Historical Descriptions Bates described what is now the North Kohala District as

Reinforcing this historical view are the remarks of Archibald Menzies, surgeon and naturalist on the Vancouver expeditions, who noted in 1793:

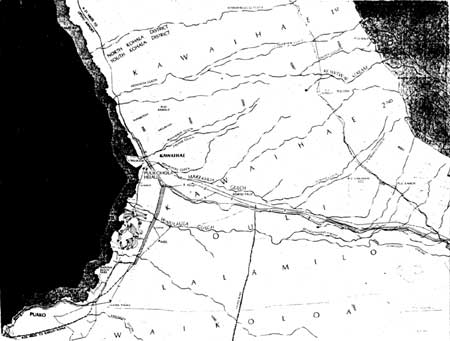

4. Settlement Patterns and Subsistence Activities a) South Kohala Francis Ching suggests several factors that might account for the sparse population and limited subsistence activity noted along the coast of South Kohala and North Kona, between Kawaihae and Kailua, by those few visitors who recorded their observations. Kamehameha's frequent wars, epidemics, and the eruption of Hualalai in 1801 might have drastically altered an earlier, more complex, aboriginal lifestyle along the west coast and been responsible for the limited occupation and subsistence activity observed in the early Western contact period by visitors such as Menzies and Ellis. Although Rosendahl points out that the few historical accounts available do not make much mention of any vegetation other than coconut palms along the desolate South Kohala coast, Handy states that sweet potatoes would undoubtedly have been grown there. He also suggests that wet taro might have been cultivated along some of the intermittent watercourses extending down from the mountains through the desolate terrain between Kawaihae and Puako. Lorenzo Lyons described Puako as

Few historical references specifically addressing present South Kohala exist. As mentioned previously, during both the prehistoric and historic periods, travelers tended to travel by water through this area rather than hiking over the rough, broken volcanic coastlands. The nature of aboriginal settlement in South Kohala was similar to that in North Kona, consisting of scattered coastal settlements whose inhabitants exploited marine resources and pursued fishing, gathering, salt production, and limited agricultural activities. Perhaps they had some success growing sweet potatoes and taro in the nearby sandy soil, along seasonal streams, and on the fertile alluvial deposits around the mouths of intermittent streams in the inland area between Kawaihae and Pauoa Bay. The major occupational area was the uplands, with scattered settlements located in the foothills of the Kohala Mountains at the northern edge of the Waimea Plain. Extensive cultivation of sweet potatoes and dryland taro took place on the slopes below Waimea and wetland irrigated taro grew along streams emanating from the Kohala foothills. There was little or no cultivation or habitation in the drier portion of the Waimea Plain close to the slopes of Mauna Kea.

b) North Kohala Along the shore from Kawaihae Bay to the north point of Hawai'i, the topography remains fairly regular, lacking the deep canon-like valleys and steep vertical cliffs characteristic of the windward side of the island. In several places along the coast are lava streams that flowed in ancient times from craters higher up the slopes. The North Kohala coast, stretching from Kawaihae around to the Waipio Valley, was populated, even densely so in the northeast section where there were perennial streams. But because of its isolation, travelers probably rarely visited the northern part of Hawai'i. Missionary Lorenzo Lyons reported to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in 1835 that

Frenchman Charles de Varigny, landing briefly at Kawaihae Bay in the nineteenth century, looked over the area and then

Kawaihae was unique among Kohala coast settlements because of the extent of European and American influences resulting from its position as an important harbor and focus of Hawaiian political and social history. In terms of appearance and livelihood, however, Clark and Kirch surmise that most other settlements on the leeward Kohala coast were probably similar in many respects. Inhabitants were fishermen, dependent on the sea for resources rather than on the dry, barren, treeless coastal area. Major settlements on the Kohala coast north of Kawaihae were Owawalua, Hihiu, Mahukona, Koaie, and Kipi. South of Kawaihae, the primary towns were Puako, Kalahuipua'a, and Anaehoomalu. Occupants of the Waipio Valley lived by taro cultivation, the surplus of which was taken to Kawaihae. According to Menzies, during a walk from Kawaihae to Waimea he met several people carrying surplus produce from upland plantations down to the coast to market "for the consumption was now great, not only by the ship, but by the concourse of people which curiosity brought into the vicinity of the bay [Kawaihae]." c) Interior The rugged dome of Kohala Mountain the oldest of the island's volcanoes, now long dormant constitutes the central area of the Kohala District. The high plateau between Kohala Mountain and the northern slopes of Mauna Kea is known as Waimea. It not only possesses one of the finest mountain climates in the islands, but also provides good grazing for cattle. The forested areas of Mauna Kea and other inland parts of the island offered a safe and pleasant haven and luxuriant pastureland for hundreds of wild cattle descended from the pair Captain Vancouver left at Kawaihae in 1793. By the early 1820s, cattle pens near Waimea held wild bullocks that were lassoed or trapped, shot, then salted, and taken to Kawaihae for shipment or trade. The availability of this salted meat made Kawaihae a favorite provision stop for whaling ships. The Reverend William Ellis noted that the first cattle brought by Vancouver were

Sheep also thrived in the rich fields of Waimea. Settlement on the higher elevations of Mauna Kea and Mauna Loa, however, was precluded by the cold temperatures. |

||||||||||

|

Chapter 7: Pu'ukohola Heiau National Historic Site Back to Contents Back to History |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |