A

Cultural History of Three

Traditional Hawaiian Sites

on the

West Coast of Hawai'i Island

Overview of Hawaiian History

by Diane Lee Rhodes

(with some additions by Linda Wedel Greene)

|

Chapter 8:

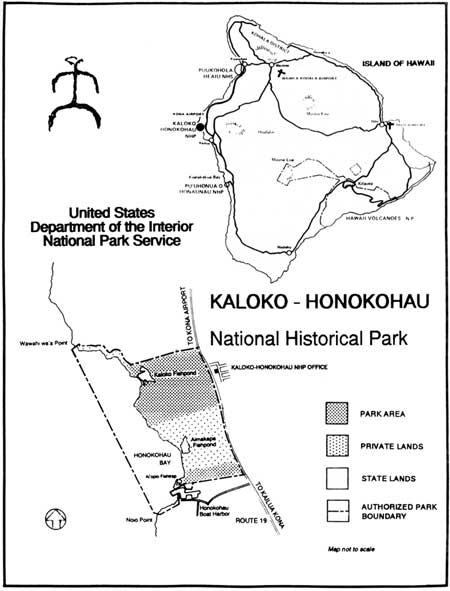

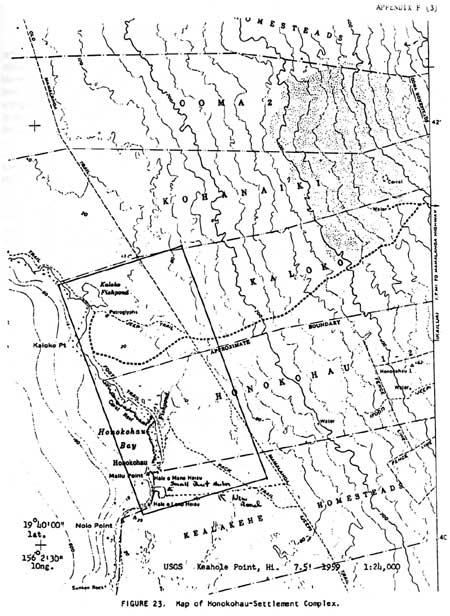

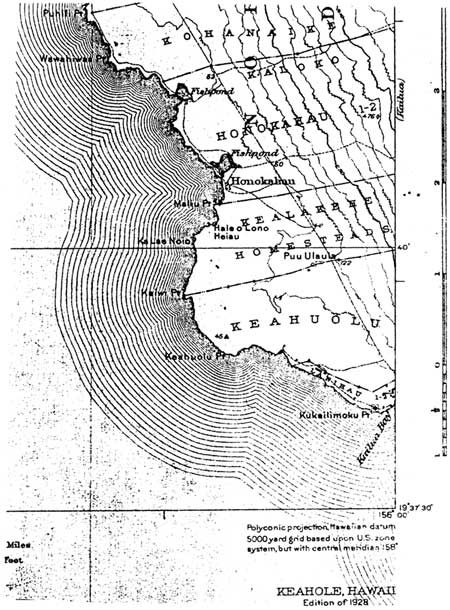

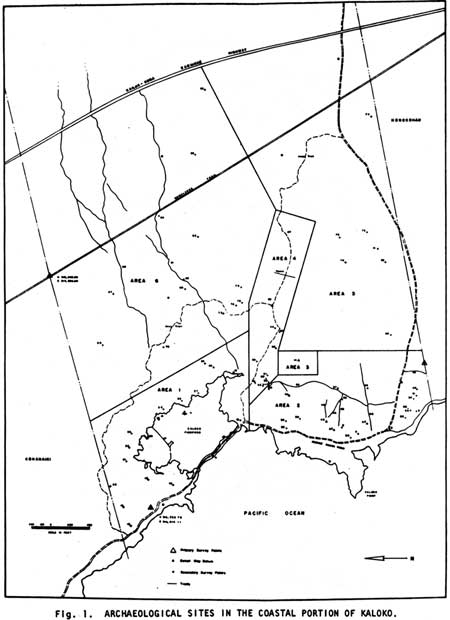

Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park A. Setting About three miles north of Kailua-Kona lies the rugged lava-covered shoreline comprising Kaloko-Honokahau National Historical Park. This area includes those lands makai of the Queen Ka'ahumanu Highway (Route 19) in the ahupua'a of Kaloko and Honokahau.

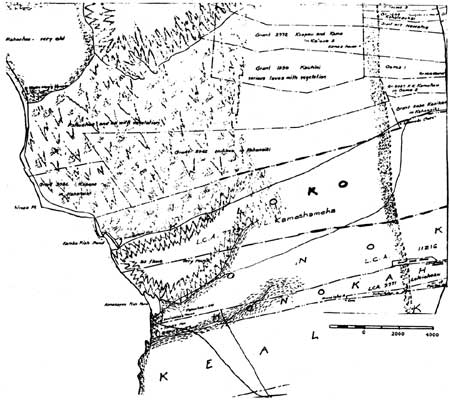

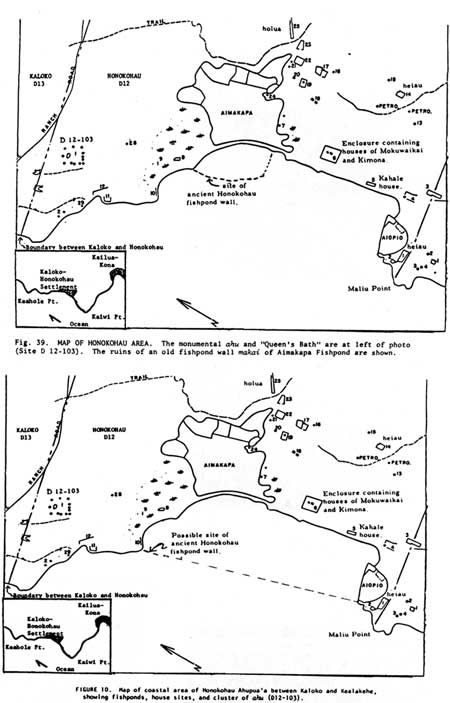

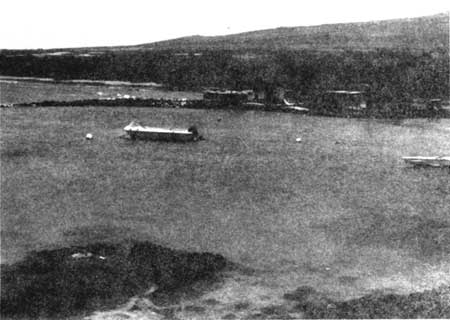

The area of broad lava fields north of Kailua-Kona resulting from volcanic flows as recent as the 1800s is called Kekaha a name designating a dry, barren, and harsh land. This portion of the Kona Coast consists of flat open areas with scattered grasses among the convolutions of rugged lava. The jagged terrain makes foot travel almost impossible, a problem that the early Hawaiians addressed by means of painstakingly built trails. In 1823, walking northwest from Kailua toward Kaiwi Point, the missionaries Asa Thurston and Artemas Bishop noted neat houses shaded by coconut and kou trees erected on top of the lava flows along the shore. Small gardens in the few patches of soil among the rocks produced sweet potatos, watermelons, and even some tobacco. The last eruption prior to their visit had been in 1801, that outflow from Hualalai having destroyed villages, agricultural fields, and fishponds on its way to the sea, where it re-formed the coastline. The lack of rainfall in this area made large-scale agricultural production impossible, but several other advantages enabled establishment of a settlement that lasted well into the nineteenth century. These included calm seas with a shallow canoe landing area, plentiful marine resources, and a variety of plants and flowers that served medicinal and dietary needs as well as furnishing material for making fishnets and for thatching simple shelters erected on the pahoehoe and 'a'a lava flats. Cool, brackish springs provided a sufficient water supply. The use of these pools was dictated by the kapu system, which designated some of these for drinking, some for bathing, and others for washing utensils or clothes. Despite the dryness and hostility of the environment, the early inhabitants of the Kaloko-Honokahau coastal settlements devised successful adaptive methods of growing supplementary food items such as sweet potatoes and gourds upon the lava beds. The husks of dry coconuts, immersed in water until well soaked, and then placed around the plant roots provided moisture and protected against direct exposure to the harsh sun. Stone enclosures built around the plants provided support for vines, deflected the wind, and lessened the effects of the afternoon heat. Archeologist Robert Renger theorized that the presence of these agricultural structures enabled a different type of adaptation to the environment in this area one in which agricultural production along the coast supplemented both the marine resources and the products of the upland. The most important subsistence features of this shoreline, and those that imbued the area with such importance for the ancient Hawaiians, were its fishponds. Of the three structures within the park, two were originally inland bays converted into ponds by stone walls constructed across their mouths, isolating them from the sea except for controlled water movement through makaha (sluice gates). The third feature, a fishtrap, was formed by arcing a stone wall from the shoreline out to a protruding point of land. B. Chronology of Settlement In a new publication currently in press, Archeologists Ross Cordy, Joseph Tainter, Robert Renger, and Robert Hitchcock, on the basis of historical accounts and archaeological data, have postulated the social, economic, and physical development of the Kaloko-Honokahau area over the years. The following information is taken from their study. 1. A.D. 900s-1700s The authors believe that small permanent settlements in the leeward portions of Hawai'i Island began by the A.D. 900s to 1000s, and possibly earlier. These would have occurred near favorable water sources, Kaloko bay probably having been one of the most sheltered and inviting large inlets along the Kona Coast. Coastal habitations had expanded by the 1200s, utilizing inland fields as well as sea resources for subsistence. The Kekaha lands north of Kaloko and extending to Kohala are thought to have undergone initial permanent settlement beginning in the 1400s, with subsequent occupation of the coast north and south over the next few centuries. Sometime during the period of 1580 to 1600, Laeanuikaumanamana, the kahuna-nui of the ruling chief, Liloa, acquired the Kekaha region. It is thought that the construction of fishponds at Kaloko and Honokahau began during this time, with Kaloko Fishpond dating from at least the 1400s to 1500s During the 1600s to 1700s, as the Kona Coast population grew with the establishment of the royal residence of 'Umi-a-Liloa at Kona and the consequent increased demand for food production, Kaloko also increased to probably almost 200 residents. It continually supported a higher population than other Kekaha areas because of its fishpond and extensive inland field system. It was the presence of these resources that resulted in residence at Kaloko by a high chief for at least part of the late prehistoric period. The authors suggest that Kaloko ahupua'a had been given to Kame'eiamoku, a high chief and one of the counsellors of Kamehameha, as well as one of the heirs of the Kekaha lands, the area having been a periodic residence of that family from his grandfather's time. A specific site within the park has even been identified as a chiefly residence. At some time during this period Kaloko's large heiau was built. Such structures were occasionally constructed away from the major centers of government, serving as luakini, ahupua'a heiau, or as a high chief's personal hieau. It is possible the "Queen's Bath," an anchialine pond, and its associated cairns is also a religious site constructed during this period, perhaps as an ahupua'a shrine, although its precise use has not yet been determined. 2. Historic Period (1800-1900) Major changes occurred along the Kona Coast in the early historic period. Drastic depopulation resulted from inhabitants leaving the coastal settlements for the port towns of Kailua and Kealakekua, resulting in a decline in agricultural production and in the utilization of marine resources. Diseases; the abolition of the kapu system; and the removal of the central government to O'ahu and Maui all contributed to the dissolution of the early settlements. By the early 1800s, Kaloko was still an identifiable community, containing about six households near the coast, but with no high-ranking occupants in residence. These coastal habitations centered mainly around the fishpond. A few scattered inland residences remained. Although the abolition of the ancient religious system probably ended formal use of the heiau and other religious shrines in the area, the already declining population and the movement of the high chiefs of Kekaha to Honolulu may have instigated this move much earlier. Subsistence still depended on agriculture and marine exploitation. By the 1830s to 1840s, the coast was being abandoned, with some resettlement occurring in the uplands zone. Only a single household, that of a caretaker, occasionally occupied the area around the fishpond. Hawaiian ali'i had always highly valued lands containing fishponds as a dependable source of a continuing and plentiful food supply. The Kaloko and 'Ai'makapa fishponds were among the largest along the Kona Coast and added considerable value to the lands on which they were located. They were probably the primary reason that ali'i used this area for recreational and ceremonial purposes. The 1848 Great Mahele resulted in almost all lands with fishponds being selected as private property by members of the ruling family. To Lot Kamehameha (Kamehameha V), a grandson of Kamehameha, went the lands of Kaloko and Kaupulehu, both supporting fishponds. Kaloko Fishpond was considered a very valuable resource, later having its own overseer who sold its products in Kailua. Kamehameha's granddaughter, Kekauonohi, received the ahupua'a of Honokohau-nui, containing the large 'Aimakapa Fishpond. W.P. Leleiohoku, heir of Kuakini, Ka'ahumanu's brother, received the smaller 'Ai'opio Fishtrap in Honokohau-iki. The land that Lot Kamehameha received in Kaloko ahupua'a included all acreage except cultivated lands (Kuleana grants) awarded to commoners, which numbered twelve adjacent to or near the main road around the island. A Catholic school with forty-five students was listed in Kaloko in 1848. Government records show that in 1857 nineteen people were paying taxes in Kaloko; this number reached twenty-three in 1860. In her discussion of the population changes in Kaloko through the years, Kelly surmises that the entire ahupua'a of Kaloko might have supported up to 400 people at one time. The Mahele wrought numerous changes by initiating a new system of land division and the transition to a cash-based economy. Crops and produce from Kaloko Fishpond were taken to Kailua-Kona and the arid Kekaha region for sale. The coastal trail connecting Kekaha villages was abandoned as traffic moved to the trails connecting the upland communities. The Mamalahoa Trail, or Lower Government Road, farther away from the coast and inland of the prehistoric coastal King's Highway, was constructed between 1835 and 1855. The Mahele and subsequent awarding of private claims probably also forced some of the inhabitants off their lands, either into outlying areas or into one of the larger port cities such as Kailua or Kawaihae. Eventually the aggrandizement and fencing of large portions of land by ranchers also served to discourage smaller native landowners. Princess Ruth Keelikolani acquired Kaloko by deed in 1874 as the sole heir of Kamehameha V. She leased the ahupua'a of Kaloko to three lessees for five years, but exempted the fishpond. A second five-year lease was granted to two of these men in 1881. After Ruth Ke'elikolani's death in 1883, her sole heir was Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop. Upon her death in 1884, Kaloko was sold to C. H. Judd, trustee of the estate of King Kalakaua and Queen Kapiolani. (John A. Maguire of the Huehue Ranch obtained Kaloko from that estate in 1906.) The area around Kaloko Fishpond began losing its identity as a community beginning in the 1880s, when permanent settlement started moving upland where cash crops could be grown, the population focusing on the Kohanaiki Homesteads. Social and economic ties were expanding outside the Kaloko area as the shoreline was virtually abandoned both here and in neighboring ahupua'a. The Kaloko Fishpond caretakers relied completely on cash sales of its produce. J.S. Emerson's ca. 1888 map of North Kona shows only a few houses along the Kaloko-Honokohau coast: that of Kealiihelepo on the east edge of Kaloko Fishpond and those of Kalua and Beniamina between 'Ai'opio and 'Aimakapa fishponds in Honokahau.

Ultimately large ranches began leasing and purchasing the lands formerly owned by Hawaiian chiefs. Ownership of the Kaloko ahupua'a, excluding the kuleana grants, passed into the hands of the later Huehue Ranch operation. Subsistence in Kaloko ahupua'a from here on began to depend on the small-scale household farming in the uplands, which had shifted primarily to cash crops by the 1880s; on sales of fish from Kaloko Fishpond by its caretakers or lessees in the markets of Kailua-Kona; and on cattle raising by the Huehue Ranch Plantation agriculture began in Hawai'i in the mid-nineteenth century, after the decline of the whaling trade and of the demand for ship provisioning that had given impetus to the native agricultural system. Plantation agriculture greatly altered the native social and economic systems. Many native Hawaiians would not work as laborers in the cane fields. Others were either forced to migrate to the upland plantations to work under this system so foreign to their traditional way of life or to move to larger towns, such as Kailua or Honolulu, to find other means of subsistence. The continuing prosperity of the plantations created a continuing need for fieldworkers. In addition, then, to new tools, agricultural practices, and forms of landownership, Western-style plantation agriculture introduced foreign contract laborers. Chinese, Japanese, Portuguese, Korean, and Filipino immigrants soon began arriving to work on the plantations. Coffee raising was a growing industry in Kona in the 1880s. A large number of coffee plantations filled the hills behind Kailua. These trees grew in narrow strips or belts of volcanic land on the leeward slopes of Hualalai and Mauna Loa. Small-scale coffee operations also existed around Kaloko and Honokahau in North Kona. Few written records exist about the Kaloko coast from the latter half of the nineteenth century through the turn of the twentieth. What little is known exists primarily only in the memories of older Kona District residents. As the archeological record bears out, many of the sites in this once heavily populated area were gradually abandoned in the middle and late nineteenth century due to a combination of factors causing heavy population decline, including culture change, disease, new land laws, and a growing desire to move to urban centers. At that time the remaining inhabitants tended to cluster around the fishponds in the area. Honokahau village ca. 1913 held about a dozen houses along the beach. At Kaloko at this time, only one house is mentioned, near the fishpond probably that of a caretaker. The Honokahau settlement continued to be inhabited as a Hawaiian village until about 1920, when people left it due to its isolation it was accessible by sea only in small boats and by land only on foot or horseback. The site was later occupied by Filipino fishermen, living in shacks on the shore. The Filipinos who obtained leaseholds on the Frank Greenwell property had come to Hawai'i beginning in the 1920s. After the expiration of their work contracts, many stayed on, moving from the plantation camps down to the beach. 3. Historic Period (1960s-Present) Kaloko continued as a working domestic and commercial fishpond during the early part of this century, the main seawall undergoing constant repairs. Between 1943 and 1961, it was leased to a resident of Kailua, who cemented several sections of wall to minimize maintenance. He also built a jeep trail from Kaloko to Kailua over which to ship fish from the pond to market. After that lease expired, the coastal area was sporadically used by fishermen and campers, who mostly occupied the coconut grove at the south end of the seawall. Kona's resort/development boom started in the late 1960s, aided by construction of the Queen Ka'ahumanu Highway, which provided easy access to the seaward portions of North Kona and South Kohala. A 1972 federal court memorandum stated that the Kaloko-Honokohau area remained rural in character, with its inhabitants still relying on the ocean, as well as the land, for their subsistence. The bounty of the ocean and fields kept them independent and off public assistance. Today, under permits first issued by the Greenwells and later by the National Park Service, a few huts of fishermen dominate the Honokohau shoreline around 'A'iopio Fishtrap. A final development spurring further activity in the area occured when the 1965 River and Harbor Act authorized construction of a small boat harbor, which began in 1968 and was finished by March 1970. (Although located in the ahupua'a of Kealakehe, it is referred to as the Honokohau boat harbor.) Because of the basaltic lava that had to be removed, many tons of explosives were used to form the facility, which included an inshore harbor basin, entrance channel, main access channel, rubble wave absorbers, and a wave trap. Its total accommodation was planned at more than 400 boats. Construction of the boat harbor resulted in destruction of some archaeological sites, but they were of marginal value and were salvaged prior to their loss. This construction added another dimension to activity along the coast, providing impetus for planning further resorts there and housing in the upland areas. C. Social and Political Structure of the Prehistoric Community The number of recreational and ceremonial structures that remain in the park, especially in the vicinity of 'Ai'makapa Fishpond, suggest intensive use of the area by ali'i. Reportedly the armies of Kamehameha, who housed his court a short distance south in Kailua, rested and refreshed themselves at Kaloko-Honokohau during long marches. Archeologist Ross Cordy has formulated some interesting societal data in his studies of prehistoric social change, postulating that two social rank echelons were present at Kaloko. Only commoners resided there between A. D. 1050-1100 and 1400-1450, with an overlord probably living elsewhere in the district. The upper (high chief) echelon was present sometime between A.D. 1450-1500 and 1600-1650. Cordy also believes that Kaloko was a discrete community with identifiable boundary features, including unoccupied buffer zones to the south and north between it and the houses of neighboring settlements. A religious cairn site ("Queen's Bath" area) marked its southern border. He believes that other features, such as an internal trail network between permanent sites and the presence of a major temple and a cemetery, also indicate a community entity at Kaloko. Two researchers recording the oral traditional and social history of the Kaloko-Honokohau area under the auspices of the Bishop Museum gathered information on the kahuna hierarchy that ruled there during ancient times. According to that information, the high priest Pa'ao brought in a king named Pili to set up a new regime to replace the chaotic one Pa'ao found on the island. This was the beginning of the religious hierarchy that characterized Kaloko-Honokahau. Establishing his residence on a hill overlooking Kawaihae, Pili ruled Kohala and Kona through chiefs stationed at Kawaihae, Honokohau, and Palemano Point, Ke'ei. Communication in times of danger or conflict consisted of signal fires that could be seen over long distances. These chiefs governed activities in their respective areas and maintained communications with their high chief. Makakilo, the chief at Honokohau, ruled North Kona from his base of operations at Pu'uoina Heiau. He also directed fishing operations. His home was reported to be on the first terrace of the heiau, closest to the ocean. A connection between the heiau and fishtrap is suggested by the fact that, in connection with his supervision of fishing activities, he reportedly held fish in the pool prior to distribution. Mano succeeded Makakilo, establishing his residence on the second terrace of Pu'uoina. The next kahuna chief, Kaumanamana, lived on the top level of the heiau. Kanaka-leo nui his successor, set up his base at Keauhou and commuted to Honokohau to direct activities there from the bluff above 'Aimakapa. Another famous ruling chief was Kekuaokalani, the highest-ranking kahuna on Hawai'i at the time of Kamehameha's birth, and the same person who, left as guardian of Ku-ka'ili-moku by Kamehameha, lost his life opposing Liholiho's abolition of the kapu system.

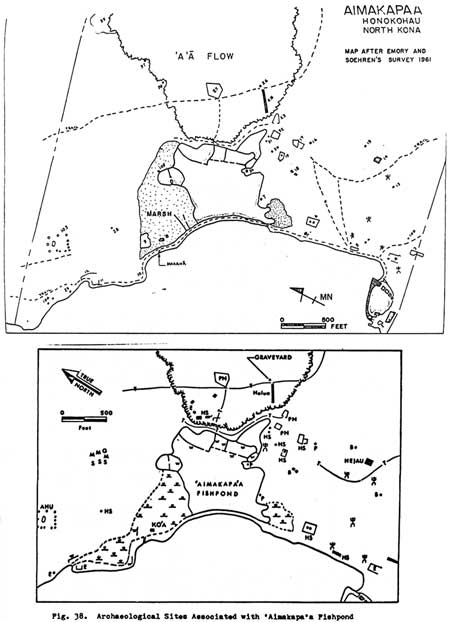

D. Relationship of Prehistoric Kaloko with Neighboring Ahupua'a Robert Renger explored the relationship that might have existed between Kaloko and the neighboring ahupua'a of Honokahau and Kohanaiki. He concluded that because the distribution of archaeological sites between the three areas was not continuous, there was probably not much interaction between them. This might have been because in early times usually only ali'i had much mobility across ahupua'a, although numerous trails between the coast and uplands signify considerable interaction within the ahupua'a by the common people. Renger theorized that only with increasing population decline in the Kaloko area was there more interaction along the coast between Kaloko and Kailua. In consonance with this line of thought, another report suggests that the name Honokohau Settlement on the national historic landmark form is misleading. Its writer points out that although strong social and kinship ties existed between people in the same ahupu'a' living on the coast, inland, or between these two areas, social ties were much weaker between people living in different ahupua'a, even if they were located next to one another on the coast. Because the area of Honokohau Settlement National Historic Landmark included the coastal sections of three separate ahupua'a Kaloko, Honokohau, and Kealakehe it would not have comprised a single integrated settlement, but three habitation areas that constituted the coastal portions of inland-coastal cultural complexes. And within these, there probably would have been closer social ties between the makai-mauka people within the same ahupua'a than between the coastal people of the different ahupua'a. E. Summary of Prehistoric Development Briefly then, research suggests that although originally established as an outlier settlement of another community, Kaloko possibly had become a unified community after A.D. 1200-1300. The coastal village was composed of several residential groups, within which one household was probably dominant in certain activities, such as religious observances. In addition to this low-level, horizontal division of authority, a hierarchial pattern of authority existed in the form of a chief who exercised control over the political and religious functions of the community. Prior to and after A.D. 1490-1610, this chief lived elsewhere in the district; during that time period, however, he apparently resided in Kaloko. No exact population figures for the settlement are available, but it probably supported from 60 to 100 people. In Kaloko, as in other ahupua'a, agricultural activities took place in the uplands while marine exploitation supplemented by the artificial raising of fish occurred along the shore. In other areas, these pond fish were intended only for chiefly consumption; it is uncertain if this was the case at Kaloko. Drinking water was available in brackish pools near the settlement, which were linked to the households by a trail system. These same generalities probably hold true for the Honokohau coastal settlement area as well. F. Historical Associations 1. Earliest Reference to Kaloko-Honokohau Area Samuel Kamakau presents the earliest traditional reference to this region when recounting a secret trip made by a spy of the chief of Maui to investigate the west coast of Hawai'i. When asked where he had gone and what he had seen, the spy reported, among other things, visiting "large inland ponds" at Kaloko and Honokahau. According to genealogical calculations by Marion Kelly, this probably occurred in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, testifying to the antiquity of these fishponds. Historically Kaloko's closest ties were to the Kona chiefs and particularly to Kamehameha's court at Kamakahonu in Kailua-Kona, a village that was probably dependent on the pond for supplemental food and on which the later caretakers of the pond depended for cash sales of fish. 2. Use as Burial Ground for Ali'i The Kaloko-Honokohau settlement area contains burial places for the dead. It is also characterized by a number of secret caves and lava tubes that figured prominently in early Hawaiian folklore as the burial place of high-ranking ali'i. As described in an earlier section of this report, funeral rites connected with the death of ruling chiefs of Hawai'i involved complex initial ceremonies that prepared the body for afterlife, followed by secret burial of the bones. These were entrusted to loyal followers whom the deceased had previously designated. Burial took place at night to prevent disclosure of the hiding place and desecration of the remains, which might result in transference of the deceased's mana to an enemy. 3. Traditional Burial Site of Bones of Kamehameha An early traditional reference to the area in the late eighteenth century mentions the burial in a hidden cave at Kaloko of Kahekili, the ruler of Maui. However, the most significant burial ceremony traditionally reported to have taken place there is that of Kamehameha, although there is no firm proof of this event. His bones were supposedly transported by canoe from Kailua to Kaloko, where the bearers of the royal remains met the man in charge of the secret burial cave, and together they placed the bones in the same depository used for Kahekili. Kamakau presents a description of this burial place, relating: Kaloko [pond] is another famous burial pit; it is at Kaloko, in Kekaha, Hawaii. [In a cave that opens into the side of the pond] were laid Kahekili, the ruler of Maui, his sister Kalola, and her daughter, Keku'iapoiwa Liliha, the grandmother of Kamehameha III. This is the burial cave, ana huna, where Kame'eiamoku and Hoapili hid the bones of Kamehameha I so that they would never be found. Kamehameha's burial place has been a subject of long conjecture, and will probably never be identified beyond doubt. On the basis of traditional sources, however, and on the basis of a lack of any solid evidence for an alternative site, it is thought to be at Kaloko. In 1887 King Kalakaua designated a man named Kapalu, who had guided him to a burial cave at Kaloko in which he supposedly beheld Kamehameha's bones, as overseer and keeper of the "Royal Burial Ground" at Kaloko. A year later Kalakaua wrote that he ordered Kapalu to retrieve the bones, which the king took to Honolulu and deposited in the Royal Mausoleum in Nu'uanu Valley. There is some question as to whether the bones were authentic and differing accounts exist as to what happened to them in later years. Barrθre, in commenting on the Kamehameha burial question, states: it is obvious that conflicting stories were given by informants named and unnamed since the early 1820s. The earliest stories were no doubt purposely misleading; the later ones are mainly versions of the earlier, with the embellishments to be expected in the retelling of oral traditions. If, despite vehement denials, the bones Kalakaua obtained at Kaloko and deposited in the Mausoleum in Nuuanu were indeed those of Kamehameha, they were spirited away from there before March of 1918, and this story too becomes but another version of the tale of the bones. Let those who will, profess knowledge of the hiding place of the bones of Kamehameha "The morning star alone knows. . . ." 4. Association with Kamehameha II Another early reference to the Kaloko area states that after Liholiho's meeting with the ali'i at Kawaihae shortly after his father's death, when discussions were held to resolve political and economic issues plaguing the kingdom, the young heir went to Honokohau to consecrate a heiau. Because he was intoxicated, however, the ritual was considered imperfect. It was immediately after this incident that he returned to Kailua and abolished the kapu system. G. Description of Resources 1. Fishponds Fishponds are impressive examples of native prehistoric engineering/technological achievements and comprise one of the many effective techniques Hawaiians used in adapting to a sometimes hostile environment. On the North Kona Coast most of the land is covered with lava that has not yet decomposed to the degree that it produces enough soil for large-scale agriculture. The dry and bleak environment of the Kekaha region between Honokohau and 'Anaeho'omalu was somewhat ameliorated by the presence in ancient times of nineteen major fishponds. Enabling a larger population by bolstering food resources, these ponds became the focal point of settlement and social organization in the area. Very few fishponds exist on Hawai'i Island, because many are being filled in to create more land for housing developments. The two at Kaloko-Honokohau, therefore, comprise some of the park's most significant and unique resources. Kaloko is a loko kuapa, or walled fishpond, formed by sealing off a small bay. 'Ai'opio Fishtrap was built by constructing a stone seawall arc from the shore to form an enclosed body of water. It is considered a fishtrap rather than a fishpond because it lacks a sluice gate. 'Aimakapa Fishpond is a lagoon formed behind a barrier beach. Kaloko Fishpond and 'Ai'opio Fishtrap are the only remaining large Hawaiian aquacultural structures with extensive ancient foundation remains in place in relatively good condition. In addition, many prehistoric and historic sites associated with them and their use are present. 'Ai'opio is the only fishtrap on the island of Hawai'i, and in addition to its good state of preservation, is a significant example of one aspect of prehistoric fishing technology. One of the general settlement types identified for the Hawaiian Islands is referred to as an agglutinated pattern. This pattern is characterized by high population density, a grouped community, clustered residential sites, and clear boundary delineations between the cluster and sites outside it. Agglutinated sites tend to be found along the shore in coastal areas with sandy beaches and safe canoe anchorages that offer good fishing and surfing possibilities in other words, generally idyllic settings. They also are often associated with people of high status. The Kaloko, 'Aimakapa, and 'Ai'opio sites are all representative of the agglutinated settlement pattern. All three exhibit a density of habitation features and the presence of temples and shrines, as well as canoe and net sheds supporting fishpond maintenance and harvest. These sites did not support a very large population, however, probably indicating that the pond harvests were not generally available for public use. b) 'Aimakapa Fishpond 'Aimakapa, the larger of the fishponds, comprises about fifteen acres. It is a loko pu'uone type pond, a large natural water area trapped behind sand dunes. It was originally much larger, including another fifteen acres that are now marshland. A stone-lined channel cut through the beach once formed the sluice gate by which seawater entered the pond. 'Aimakapa also has secondary walls, forming at least six compartments for separating fish. The pond is intact, though somewhat overgrown. It still contains awa (milkfish) and is an important wildlife refuge for native and migratory birds. Numerous sites along its shores indicate intensive human activity, particularly use by ali'i for recreational and ceremonial purposes. The nearby holua is one of eight surviving in Kona, others existing at Ka'upulehu, Keauhou, Honaunau (2), Keokea, Ki'ilae, and Okoe. It and the one at Keauhou allowed two contestants to compete simultaneously. The slide is a narrow built-up stone track covered with grass to create a slick sledding surface. The sled itself was a narrow piece of wood on which the contestant threw himself full length, attempting to remain on the track all the way to the bottom. It is said that only ali'i participated in this sport. The takeoff and runway to the brow of the a'a flow are well preserved, but the lower section of slide has been cannibalized for stones to construct two corrals on the flat below. At the head of the holua is a graveyard, while house sites and tombs are found at the base of the hill supporting the slide. Scattered petroglyphs may be seen throughout the area, as well as ancient heiau remains on the pahoehoe plain. A platform close to the Mamalahoa Trail might have been used as a gathering place for meetings and/or ceremonies. On a high point behind 'Aimakapa stands a large stone, called Kanaka Leo Nui, meaning "man with a loud voice." Tradition says that in ancient times the chief by that name stood on this stone while directing fishing activities off the coast. This pond is thought to have been in existence prior to the fifteenth century A.D. There also appear to be remains of an old unnamed fishpond seaward of the present coastline, makai of 'Aimakapa Fishpond, that are visible in the water. According to tradition, chiefs directed the activities of Kaloko-Honokohau inhabitants by issuing hand or flag (ka pa) signals to their subordinates from high places such as the bluff above 'Aimakapa Fishpond.

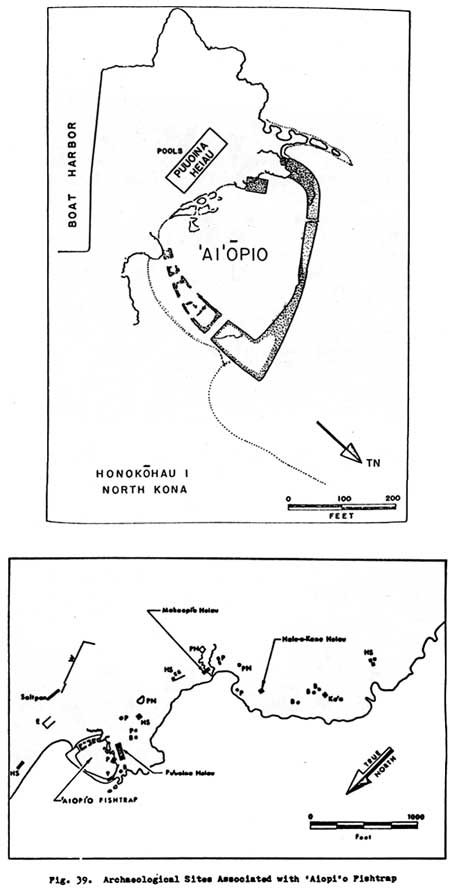

c) 'Ai'opio Fishtrap 'Ai'opio Fishtrap is almost two acres in size and roughly circular in shape. Its seaward side is separated from the ocean by a manmade stone wall, while its other sides are bordered by rocky lava headlands and the sandy beach. Fish entered the pond at high tide through a narrow channel in the seawall; it has no sluice gate. Four rectangular walled enclosures within the pond along the shoreline were probably used either as holding pens for netted fish or as lanes in which the fish were netted. Kickuchi and Belshe have suggested that, because of their proximity to each other, 'Ai'opio might have played a supporting role in the management of 'Aimakapa Fishpond, possibly providing its fish supply. House sites can be seen around the pond area, while inland are large concrete salt pans and the remains of frame houses, indicating occupancy of this area into the twentieth century.

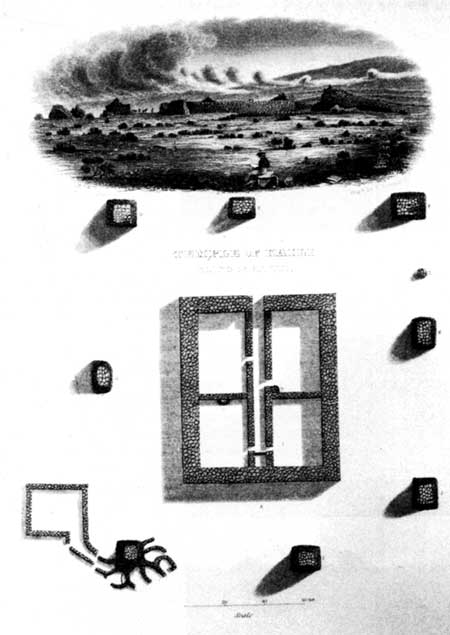

2. Heiau Other important resources within the park and nearby vicinity are the several heiau located between Wawahiwa'a Point in Kohanaiki and the Alula Bay area in Kealakehe, The two most important of these are Maka'opio (Hale-o-Lono) on Alula Bay and Pu'u'oina (Hale-o-Mano) south of 'Ai'opio Fishtrap. a) Maka'opio Heiau The fisherman's heiau known as Maka'opio, a Hale-o-Lono class of heiau, is a low rectangular platform built out into a shallow, ponded area. Its outstanding features are two great upright stone slabs, measuring over six feet five inches in height, that rise above the pavement perpendicular to the seaward face. The stones, one of which bears a petroglyph of a man about twenty-four inches high, may have represented fishermen's gods. Also present is a small ko'a (fishing shrine) comprising a large, smooth stone (ku'ula) standing on a platform. Nearby are ancient house sites, petroglyphs, and bathing pools.

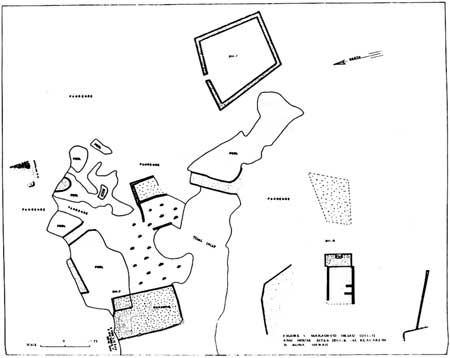

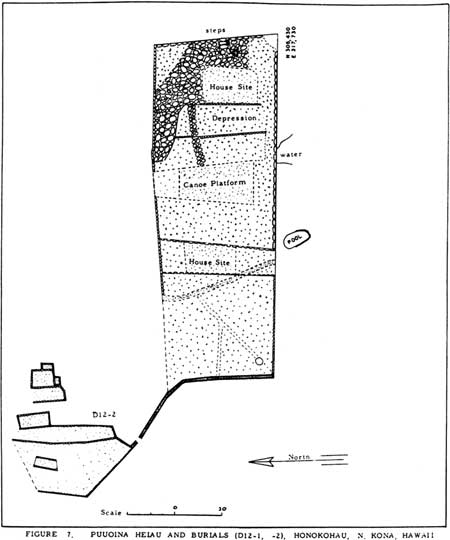

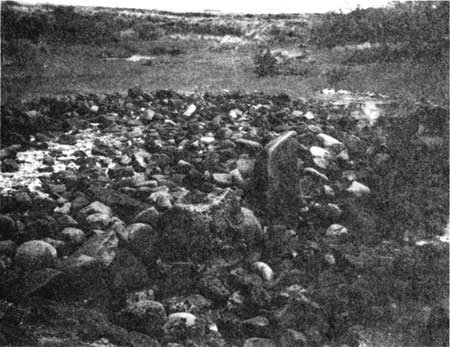

b) Pu'u'oina (Hale-o-Mano) Heiau Pu'u'oina temple, sometimes referred to as Hale-o-Mano, stands just inland from Maliu Point and measures about 50 by 145 feet. It is considered the finest example of a platform heiau in Kona. Oral tradition states that this was an operations and dwelling area for warrior priests. Standing on the south shore of Honokohau Bay, at the south side of 'Ai'opio Fishtrap, the heiau's huge waterworn boulders form an impressive structure. Some appropriation of stones for construction of a fence has taken place, and stone from the north side has been used to build nearby houses. Steps are located in the structure's east wall. The surface of the temple is divided into several segments, including raised platforms, a paved depression, and an area of waterworn boulders. Some later alterations are apparent in the structure. Found on the surface level at the east end are a house platform and a canoe platform. The heiau may have utilized the small brackish pool on its south side in connection with its ceremonies. Northwest of the heiau is a large burial platform and just north of the graves a platform ruin lies in the water. The seawall of 'Ai'opio Fishtrap begins at the heiau's northeast corner. Another small platform ruin exists in the water a few yards east. Another platform, on which a hut has been erected, is located at the east end of the seawall. There is no known documented relationship between the fishtrap and this temple, although oral tradition presented earlier did identify the trap as a holding area supervised by the chief living at Pu'u'oina. It is thought that Pu'u'oina was an important base of operations for those governing Honokohau and North Kona. Its importance derived from its location near the ocean and the 'Ai'opio Fishtrap, which facilitated directing the community's important fishing activities.

3. Graves The significance of grave sites scattered throughout the Kaloko-Honokohau area was discussed earlier. Grave features in the park consist of burial cists, graves bordered with stones, pit burials, burials in natural depressions in the pahoehoe, platform tombs, and graveyards and cemeteries. To disturb such sites would be a great sacrilege. 4. Trail Systems Historian Russell Apple describes four major types of Hawaiian trails: Type A are single-file prehistoric paths; Type B came into use after European contact and the introduction of horses. They were a modification of Type A trails, with curbstones and causeways; Type C were two horse wide and built in straight lines between major points, cutting off the small coastal settlements. The Mamalahoa Trail, a straight, curbed, cut-and-fill path, is a good example of this type. They were commonly built by labor forces conscripted by the island governors during the mid-nineteenth century. With the introduction of wheeled vehicles, Type C trails were modified, widened, and realigned into Type D trails. In prehistoric as well as historic times, trail networks were important adjuncts to the Hawaiian social and economic systems. They served both as major routes between specific land units and social groups and as internal networks of lesser trails for transportation and communication within an ahupua'a. The earliest trails were designed only for foot traffic because the people had no draft animals or wheeled vehicles. They were not particularly smooth, flat, or easy to follow. Sometimes they meandered, based on the availability of rocks for marking the route. Residents of an ahupua'a built trails running mauka-makal as soon as they settled into an area to facilitate food gathering and goods exchange. These goods were transported by sling nets or carrying poles. Major commercial trails between ahupua'a, villages, and towns running on the contour of the island along the coast were a necessity and were quickly incorporated into the overall trail system. Other major routes were built over the mountain ranges to connect communities on opposite sides of the island. One very important trail, the King's Highway, borders the Kona Coast and is still visible from the Queen Ka'ahumanu Highway between Kawaihae and Kailua. It was used for commerce, troop movements, carrying messages, collecting taxes, and other government activities. It was considered very safe for travel, being specifically under the auspices of King Kamehameha I's "law of the splintered paddle," which directed that any traveler could use the highway without fear of being molested. It led from Kawaihae to Kiholo, upslope to Huehue, and down again to Kaloko, Honokohau, Kealakehe, and Kailua. The trails of Kekaha reflect various stages in the development of the region, as relations were established between coastal and inland villages and between coastal settlements. Several examples exist within this park of the most ancient footpaths of the area, comprised either of steppingstones of smooth waterworn cobbles brought from the seashore and placed three to four feet apart or of flat lava slabs laid over the rough a'a flows. White coral pebbles that reflected moonlight marked some paths for night travel. Other paths across a'a flows consisted of simple, worn, trough-like depressions formed by feet crushing clinkers into a pebble-sized bed. In some places these trails were modified in historic times for animal travel and thus some of their earliest integrity lost. Where no old foot trails existed to be modified, new horse trails were built in historic times, mainly for commercial purposes. In Kaloko-Honokohau the residents built a system of mauka-makai trails to travel and communicate with extended family members and friends. Other routes traversed the coast laterally to transport food and other goods to neighboring ahupua'a. Several trails are found in the Kaloko-Honokohau area, mostly short footpaths comprising a local trail system, used both in the prehistoric and early historic (pre-1840) periods. Some prehistoric trails modified with curbs have been identified here, as well as new, probably post-1840, straight curbed trails. Although a mauka -makai exchange system was used for many products, the produce of Kaloko and the other fishponds would not have been available for exchange and use by commoners. The public Mamalahoa Trail and the ancient coastal trail were two major routes around the island, leading south to Kailua-Kona and north to Keahole. In early times the coastal trail would have facilitated transportation of fish from this area to Kamakahonu Kamehameha's court and primary political and economic center in Kailua which probably consumed most of the products from the ponds in the area. The coastal trail ran right by 'Ai'opio Fishtrap. These trails are an important component of the park's cultural landscape, providing data on the linkages between communities. They comprise a record of local movement and sometimes include associated features such as small cairns placed as markers along the routes or petroglyphs (especially where smooth lava is found) that serve as pictorial signatures of people who passed by. Often caves or small walled shelters are found that served as resting places along longer trails. The Mamalahoa Trail is one of the most significant resources in the park, but all the trails are important in illustrating early communication, transportation, and commercial networks. Their importance to the prehistoric Hawaiian subsistence economy cannot be overlooked, because they were the lifelines for food exchange. They were a direct result of the belief that everyone had access rights to the products of the land and ocean for their sustenance. The early Hawaiian trail system made this type of utilization possible within the land unit. Along the leeward coasts these trails can still be seen and indeed many are still used today by fishermen and campers.

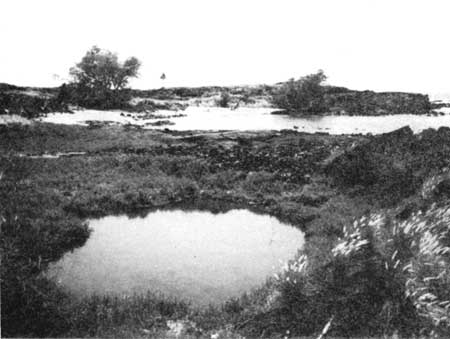

5. Ahu (Cairns) Near the boundary between Kaloko and Honokohau is a feature referred to as the "Queen's Bath." The site includes twelve lava mounds arranged in a rectangular form around a brackish pool hidden in the extremely rough a'a lava flow. Seven cairns in the southwest corner of the rectangle stand out because of their size and construction. They are graduated in height from ten feet to five feet, while the other mounds are smaller and more irregular in shape and construction. Each of the seven large structures is carefully faced with rough lava and all seven are crumbled on one side, possibly as a result of people climbing them. At the north end of the rectangle is an anchialine pond that has been modified into a bathing pool. A barely discernible trail leads to it from between the two largest cairns and continues on north. The sides of the pool have been cleared and leveled and the water lined with smooth lava blocks to form a sort of rectangular underwater bathtub. Smooth slabs have been set around the sides as seats. At the east end of the pool the lava was excavated to form an enclosure walled on three sides, the side facing the pool being open. Probably it was covered over and used as a bathing shelter. A traditional story is that "the queen" bathed here while guards on top of the cairns stood watch for intruders. Some traditions say she came by canoe to a landing nearby and was carried over the rough lava to the secluded and guarded pool in which smooth stone ledges had been placed for her comfort. One local informant stated years ago that the pool was the private bathing place of Kamehameha, who stationed his guards by the ahu. Others have suggested these cairns are boundary markers. Kelly recounts that one early ruler, Umi, used ahu like these as a way of taking census, requiring the population of each of his districts to erect an ahu to which each person living in that district contributed one stone. She knew of no such practice at Honokohau, however. One informant stated that when she and her family stayed at Kaloko for weeks at a time, they bathed in this pool. The evidence for this pool actually being used as a bathing place for a "queen" in ancient times is tenuous. Cordy and his colleagues surmise that this complex has religious significance, perhaps as an ahupua'a shrine, but this may never be known with certainty. The pool is used today by many people for bathing. Ongoing archeological survey work indicates the entire pool may be manmade.

H. Significance of Resources and Establishment of a National Historical Park In 1962 the Honokohau Settlement area, including Kaloko Fishpond, was designated a National Historic Landmark. Kaloko-Honokohau National Historical Park was authorized on November 10, 1978, encompassing about the same area as the landmark. It was established to preserve important aspects of traditional native Hawaiian culture and land use patterns in a location that contained numerous significant prehistoric and historical sites illustrating those activities. The fact that the area was preserved as a complete entity denotes the value accorded the entire grouping of structures in illustrating early Hawaiian lifeways. The area possesses strong cultural and religious associations in connection with ancient Hawaiian burial rituals, particularly those for ali'i. One very personal aspect of this close association with the dead a unique characteristic of Hawaiian culture concerns this being the traditional burial place of Hawai'i's most famous ruler, King Kamehameha I. The hundreds of virtually intact archeological sites in the park and surrounding area include heiau, fishponds, ko'a (fishing shrines), individual house platforms as well as complexes of structures, a holua (toboggan slide), several papamu (konane game boards), burials, petroglyphs, stone cairns, animal enclosures, more than 100 stone enclosures serving as agricultural planters, several ahu (stone mounds serving either as altars, shrines, or security towers), lava tube shelters, canoe landings, salt pans, and a mauka-makai trail network. There are more significant sites within this area, both in terms of number and physical condition, than anywhere else along the Kona Coast from Kailua to Ke'ahole Point. Because little use of the land here has been made since early times, it is possible to gain a fairly reliable impression of the pattern of early settlement. The resources of Kaloko-Honokohau possess esthetic, cultural, historic, economic, scientific, and emotional values for the Hawaiian people. The discussions centering around establishment of this park emphasized that it was necessary to view and evaluate its fragile resources through a sensitive and sympathetic understanding of the culture that had shaped them. Although many details of the Hawaiian religion, language, crafts, and other cultural aspects were recorded upon the creation of a written language, there is much tradition that was not recordable, but that is intangible, a part of the personal and private Hawaiian cultural makeup that is transmitted best through expressions, action, and the spoken word. It is clear that the significance of the resources in this area must be judged not only in the context of their obvious importance to the study of early Hawaiian culture but also in relation to their emotional value, their relationship to prevailing cultural attitudes that have been shaped by the experiences of the past. The hundreds of archeological sites identified in the park to date indicate prehistoric and historic occupation of the area by a large population, both maka'ainana (commoners) and high ali'i (chiefs). A very active religious-political center, its economic life, based in large part on its fishponds, was geared toward supporting the social and political status of the Kona chiefs. The remains illustrate maritime aspects of early Hawaiian culture, encompassing subsistence activities, residential patterns, social interactions, and religious practices, in addition to artistic achievements and recreational pastimes. The concentration of resources in Kaloko-Honokohau provides direct evidence that a larger population existed here than elsewhere along the coast, probably because of the presence of the fishponds, which are the only resources of this type left between Kailua and Ke'ahole Point. The park is valuable to archeologists for the study of the activities of pre and early-contact Hawaiians and changes occuring in subsistence patterns and land ownership over time. For native Hawaiians, this is a sacred place, a place where revered ancestors lived and died. Future plans are to create an environment in which to educate Hawaiians about their culture; to stabilize selected, significant historic remains; to preserve fishponds; and to manage and interpret these cultural resources in a meaningful and sensitive way to the public. The primary interpretive effort will address numerous aspects of the Hawaiian culture, including language, subsistence interactions with the land and sea, aquaculture, family systems, religious beliefs, and ancient dances, crafts, and other cultural activities.

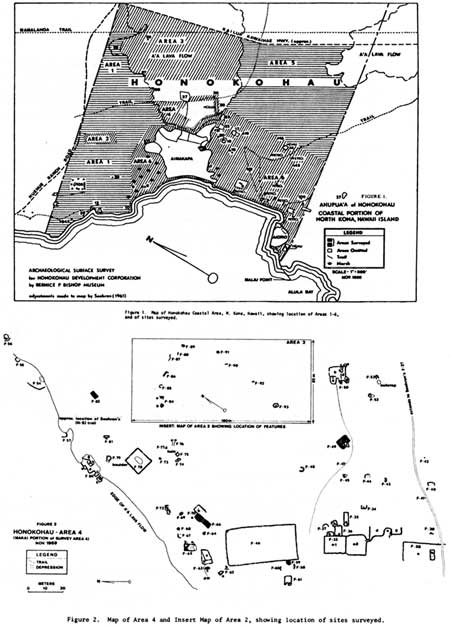

I. Archeological Research Accomplished 1. Honokohau Area In 1969 the Lanihau Corporation contracted with the Bishop Museum for a survey of the Honokohau area within the landmark where the company planned commercial development. Deborah F. Cluff conducted this reconnaisance of the seaward portion of Honokohau, mapping and recording features. The following is some of the detailed information on resources she provided that enlarges on the descriptions presented earlier in this section. Cluff noted 'Aimakapa Fishpond as a large and still functioning body of water surrounded by marsh and dense groundcover with a stretch of sandy beach on the west. She believed the area surrounding the pond offered potential for archaeological research on the adaptation of the aboriginal Hawaiians to the land and its various resources. She mentioned finding numerous sites, including paved footpaths, rock shelters, walls, scattered graves, monumental ahu, a burial ground, walled enclosures, platforms, and the holua. The area lying between 'Aimakapa Fishpond and 'Ai'opio Fishtrap and continuing east from there she found to be very important historically and archaeologically. Its features were more elaborately constructed and suggested more permanent occupation. Architectural styles indicated a culture in the process of change, as evidenced by the find of a cement tomb in the shape of an early grass house. She also found numerous petroglyphs depicting figures and objects common in prehistoric Hawai'i as well as Western motifs such as European ships and rifles. Cluff wrote that 'Aimakapa Fishpond, with its population of birds, its petroglyphs, its heiau, house platforms, holua, papamu, trails, bait cups carved in pahoehoe, and burial ground, all located in one general area, provided a unique opportunity to view numerous components of an ancient Hawaiian village. Cluff summarized that her findings substantiated that the region was important in both prehistoric and early historic Hawai'i. The importance of Honokohau's coastal portion lay in its fishponds. Her survey showed extensive use of the available land, including placement of shelters and burials on the rugged a'a beds and of crude shelters as well as better constructed house platforms and a heiau, bait cups, papamu, and petroglyphs on the pahoehoe. These areas contain information on many of the activities of early Hawaiian culture especially house construction, religious ceremonies, and burial practices. Some of the small enclosures she found appeared to have been used for horticulture, although she believed the primary reliance for food rested on marine resources. The social system was well established, Cluff surmised, with commoners living in the barren a'a and pahoehoe areas, while royalty utilized the flat region close to the fishponds and near the heiau and holua. The most recent occupation had been around the ponds where petroglyphs depict historic objects and cement was used in wall and grave construction.

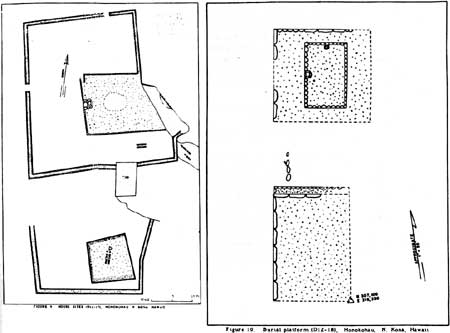

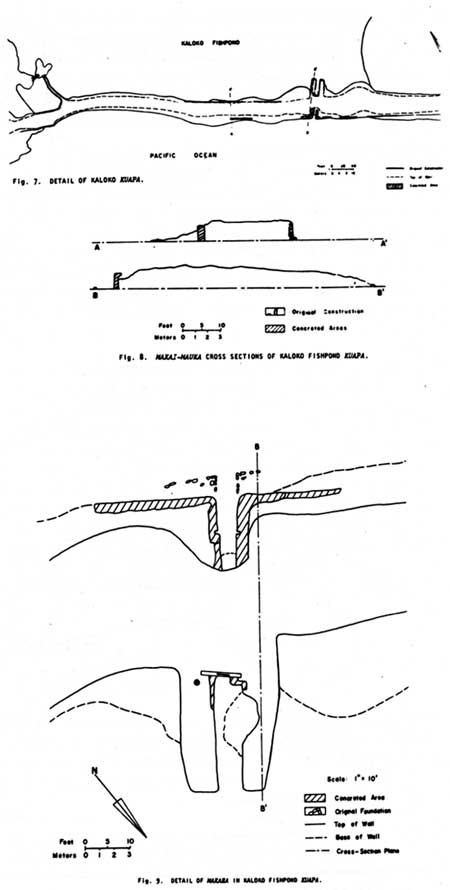

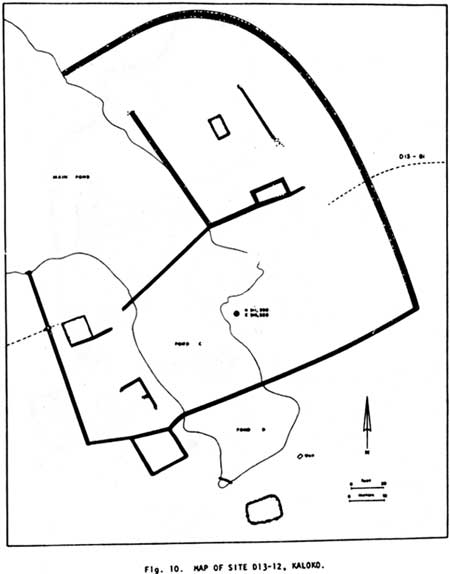

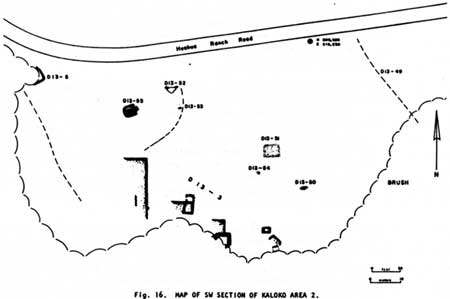

2. Kaloko Area a) Robert Renger's Work In 1970 the Bishop Museum began work in the Kaloko area of the landmark under a contract with the Kona Coast Company (Huehue Ranch). The data was to be used in planning for a major hotel and residential complex at Kaloko. Robert Renger conducted the archeological reconnaissance of the area around and including Kaloko Fishpond. Renger found at least three trails running mauka-makai and several sources of fresh water in the first area surveyed, encompassing the northwest corner of Kaloko ahupua'a and the area immediately around the fishpond. The pond itself consisted of five elements: a primary seawall facing on the ocean and the main pond area and four secondary pond walls built of faced lava fill and of varying widths. Other sites recorded in the pond's vicinity included a walled area containing a coconut grove and the remains of a frame house and another frame structure a fisherman's shack (net storage house no longer extant) on the edge of the fishpond. Fishermen and picnickers have impacted this area. The main pond seawall showed evidence of three different techniques in construction, repair, and modification. Other features nearby included a house-platform complex on the southwest side of the pond arm, a house compound surrounded by a three- to four-foot-high wall on a knoll overlooking the fishpond, a second house complex, segments of a coral-paved mauka-makai trail, a papamu, walled enclosures, possible canoe house sites, platforms, and enclosures.

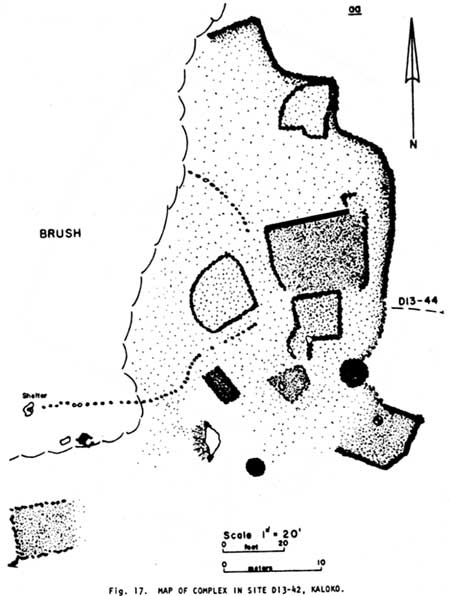

Renger found, in the area along the coast south of Kaloko Fishpond, two major trails paralleling the coast and one running mauka-makai. There were also several secondary trails connecting the structural complexes with main trails and wells. Most sites there occurred along the mauka edge of the low sand dunes on the edge of the a'a and ranged from crude slab shelters to very large paved platform complexes. Several small steppingstone trails led into the dense brakes along the edge of the a'a. Within the brakes Renger found several tube shelters and a possible pen structure. He assumed that other features were probably covered by undergrowth. Individual sites comprised house enclosures; platforms; wells; trails; a lava tube shelter and enclosure; a large complex with enclosures, platforms, ahu, leveled areas, hearths, slab shelters, and a tube shelter; circular enclosures; and other individual tube shelters.

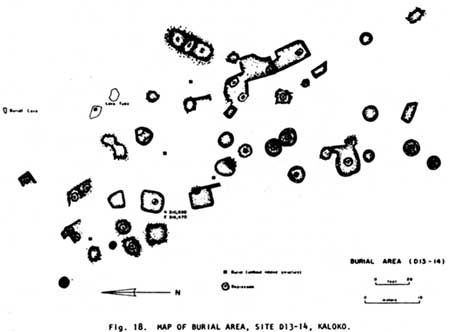

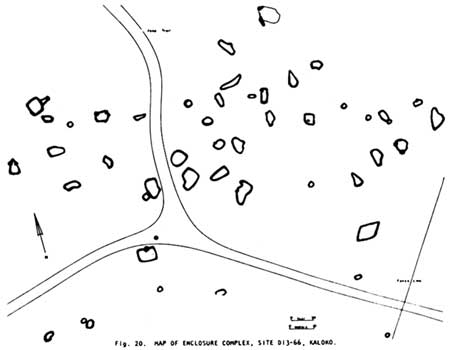

A smaller surveyed portion inland of the area described above contained a large quantity and high density of features, mostly burials. Renger found more than ten well-built platforms, several leveled areas, ahu, and two caves with more than thirty burials between them, many disturbed. The ground was composed of rough ridges of a'a forming a plateau overlooking the coast. One of the caves contained seven people buried intact in an extended position the only instance found in the area of this form of burial practice. The other cave contained seventeen secondary burials, a post-contact coffin burial, and a possible bundle burial. The next section surveyed was the northern edge of the a'a flow covering the southern half of Kaloko. There Renger found doorless enclosures, petroglyphs, a few house floors, and four tube shelters. More than fifty small enclosures, about three feet high, exist there, their walls constructed of a'a chunks. A jeep trail runs mauka-makai down the entire length of the area, seemingly following the path of an earlier trail. (This is probably the jeep trail constructed to take fish to market, maybe an earlier donkey trail.) Another area surveyed, in the southern half of Kaloko, was composed of rough a'a running mauka from the burial plateau. The mauka-makai jeep trail, Huehue Ranch road, and Mamalahoa Trail all cross the northern portion of this area. Archeological sites there consisted of one burial, six enclosures, and one possible house foundation. The last area surveyed comprised the entire northeast corner of coastal Kaloko, bisected by the Mamalahoa Trail. In addition there were two major mauka-makai trails found, one of which forked just mauka of the Mamalahoa Trail. Indications existed that these were still used by fishermen and horsemen. Archeological features included two low platforms, several ahu, two stone circles, several enclosures, and two wall segments.

In summary, Renger stated that the density and variety of features in coastal Kaloko provided many good illustrations of the types of environmental adaptation practiced by early Hawaiians. The high concentration of features, the density of the shell midden, and the number of artifacts found along the coast and around the fishpond indicated to Renger that the people exploited their maritime and fishpond resources intensively. He theorized that many of the small enclosures found were constructed for dry-land horticulture, while major trails running maukai-makai provided access to vegetables and other resources on Hualalai. The types of structures he found and their distribution provided him with some indication of social conditions there in early times. The presence of carefully constructed, massive structures and complexes around the fishpond and on the pahoehoe, for instance, suggested to him that the ali'i lived in those areas. The simple shelters and platforms on the a'a, however, were probably residences of commoners. Society within the settlement must have been based on a hierarchical social system, he explained, because the size of the kuapa across the mouth of the fishpond would have necessitated a considerable labor force over an extended period of time for its construction. Controlling and supporting with food and shelter such a sizeable body of workmen would have required a stable and well-organized social system. More recent occupation of the area had also centered around the fishpond and focused on use of marine resources.

b) New Study by Ross Cordy, Joseph Tainter, Robert Renger, and Robert Hitchcock The new study of Kaloko ahupua'a recently completed by Ross Cordy et al. presents the results of recent fieldwork in the coastal Kaloko area. It contains some revised site descriptions, records additional major features at previously recorded sites, reclassifies known sites, and provides data on some completely new sites. The authors identify fifty-eight sites in the Kaloko coastal zone, comprising twenty site types, plus five inland-oriented trails. According to their findings, sites used during the nineteenth century include the coastal cross-ahupua'a trail, Kaloko Fishpond, and several sites around it, including walled residential lots with associated trail branches, a residential complex, solitary houses, and miscellaneous walled structures. None of the sites, excluding the fishpond, the shoreline trail, and some of the walled house lots, was in use by the 1880s to 1900s. Only one house lot at a time was occupied, presumably by the pond's caretaker. J. Contributing and Non-Contributing Elements All archeological features, the fishponds, and the trail system are significant park resources. There are, in addition, natural and cultural elements that do not contribute to the significance of the area. Alien vegetation, such as kiawe, exists within the park. Wooden cabins hug the shore in Honokohau ahupua'a, and several modern jeep roads cross the settlement area. A paved secondary road provides public access from the Queen Ka'ahumanu Highway to the Honokohau Harbor, while a narrow, unimproved road leads from the major highway to Kaloko Fishpond. The physical remains of early Hawaiian culture inside the park, however, remain essentially untouched today. K. Threats to Resources As with other previously undeveloped areas along the Hawaiian coastline, Kaloko has undergone its share of planning for resort, recreational, and housing purposes. Construction of houses has taken place mauka over the last few years, and it was the possibility of resort development starting on the coast that caused the concern, discussion, and study leading to establishment of the national park. Now another resort/development phase is underway. Construction of houses is going forward in the uplands at the same time industrial structures and warehouse facilities are spreading out along the mauka side of the Queen Ka'ahumanu Highway. Consideration is being given to expansion of Honokohau Harbor, with plans being drawn for more resorts, condominiums, and other recreational facilities along the coastline north of Kailua. Viewed within this context, Kaloko and Honokohau as a national historical park may well soon be the only remaining sizable enclave in the Greater Kailua region where the coastal archaeological remains of past centuries can be viewed as a whole." This situation, of course, greatly increases the park's value. Of particular concern, then, are the possibilities of uncontrolled use of the area and the loss of significant resources that are still in private ownership. Many of the Filipino fishermen living in the area of 'Ai'opio Fishtrap, for instance, have established houses on top of ancient heiau platforms. The presence of a nude bathing area along the coast near the "Queen's Bath" attracts many visitors who picnic, fish, swim, and participate in other water-related activities. This type of use will undoubtedly increase, especially with expansion of the harbor facilities, and poses a potential threat to this fragile and unique environment. L. Management Recommendations This section has attempted to stress the significant research, interpretive, and educational value of cultural resources within Kaloko-Honokohau NHP. Because of the scarcity of fishponds in Hawai'i, those in this park should without question be preserved to illustrate the original character, type of land use, and cultural landscape of the area. In addition, they provide information on the techniques of aquaculture, which might be modified and put into use today or at the very least be a means of passing on knowledge of ancient engineering skills to the present generation to help in comprehension of their cultural heritage. These resources provide lessons in environmental adaptation as well as structural engineering. Kaloko would be a major interpretive feature if restored as an authentic fishpond after studies to determine its original form and components. All archeological features in the park should be preserved, preferably in their present state. The variety of features, their location in one area of the coast, and the amount of historical documentation and archeological survey results available make this an ideal interpretive and educational area. Many of the features around 'Aimakapa Fishpond and 'Ai'opio Fishtrap are unique. Even though little documentary evidence exists, and no historical descriptions of the area have been found, these remain a valuable model from which to gain information and form hypotheses about the Hawaiian heritage. All resources can contribute to providing a holistic view of early Hawaiian lifeways. Several house platforms and Maka'opio Heiau, located in the vicinity of Honokohau Harbor on state land, should be interpreted. The NPS is trying to work out a cooperative agreement with the state to restore this heiau. The state could plan for this area a unique park setting within which significant resources could be preserved, providing an unusual educational opportunity for harbor users. Currently, vegetation in the park consists of grasses, exotic thorn trees, and shrubs covering the ancient pahoehoe lava flow. Behind this, spreading up toward Hualalai, is the more recent covering of a'a lava. A Cultural Landscape Report should be programmed to determine the types of plants and shrubs originally present and the changes in vegetation over the years. This report would help determine a treatment plan (removal/control) for introduced alien species and for native plant maintenance. Any clearing of the pond and shore areas will undoubtedly uncover more archeological resources, possibly enabling more accurate dating of pond construction and adding to the research value and educational opportunities of the park. It has been recommended that 'Aimakapa Fishpond be preserved as a wildlife refuge. Two species of native waterbirds found there are federally listed as endangered species; 'Aimakapa provides an important habitat for them. It has also been recommended that if Kaloko is restored as a fishpond, concessions should be made to foster waterbird use there as well. Because endangered waterbirds are present in the Kaloko wetlands, the Endangered Species Act will have some affect on the kind of activities that can take place there. Planned non-native vegetation removal should be considered a high management priority for wetland habitat restoration. Later sites, such as the salt pans, house ruins, and foundations of the Honokohau community church around the fishtrap are also important educational tools because they illustrate changing land use and habitation patterns. These features resulted from a variety of economic, social, and political pressures and should be retained as showing continuing adaptation by residents of the area, both native Hawaiians and immigrant ethnic groups, to meet subsistence needs. Preservation and stabilization of significant archeological resources in the park, such as the fishponds, the village site, the tombs and associated structures near the holua, and the heiau, is an NPS management responsibility. The NPS should be intent on preserving the present appearance of these ruins and interpreting pre-European contact and historical values at each site. The full-range of activities in the area by early populations can be transmitted clearly and well through interpretive devices that do not affect the integrity of the ruins or their research value in the future. It is recommended that development within the park be held to a minimum to preclude intrusion on the area's visual integrity and destruction of the prehistoric and historic scene. Necessary facilities for visitor use could ideally be restricted to areas outside the park boundaries, except for interpretive devices needed to explain the area's significance, essential facilities such as restrooms and designated picnic areas, and whatever minimal structures are needed for visitor and resource protection in what will undoubtedly become a high-use visitor area. (A draft General Management Plan is now in press that defines development plans for the park.) M. Further Research Needs Fishponds and associated archeological sites are valuable educational resources. Kaloko-Honokohau is an especially important area because Near other fishponds, in districts and areas traditionally and historically classified as being settlements of nobility and as serving as court areas, any such archeological remains have been destroyed, leaving little or no evidence of the settlement patterns which once existed. This frequent lack of associated archeological sites has made dating fishponds very problematical. The presence of so many house sites and other structures near the ponds in this park that can be surveyed and tested give this area added significance. Much archaeological work and documentary research focusing on the park area has been accomplished in the last thirty years, resulting in extensive knowledge of the location and nature of sites and of the historical background of the Kaloko area in particular. The archeological significance of this area lies in its high research potential due to the density of sites and to the broad cross-section of Hawaiian culture that they represent. Studies to date have provided significant details about the culture along this important section of the Kona Coast and about ancient Hawaiian society in general. Kaloko-Honokohau particularly offers an opportunity to gather data on the sea-related aspects of early Hawaiian culture. Studies on the structures here and their spatial distribution can provide data on their functional uses and on the social interactions of the community. The cultural deposits could help in organizing the sequence of adaptations to the environment and help refine our present chronology of Hawaiian occupation of the islands. The interpretive value of cultural resources in this park is unique in the islands. The resources here are in such close proximity to each other and in such good condition that they can be interpreted with minimum effort. The park area exemplifies early Hawaiian coastal settlements that supported typical subsistence and social activities, although this area also sustained an active religious/political component associated with the presence of ali'i. Nowhere else on the Kona Coast does such a a diversity of sites exist, including habitations illustrating residential patterns and social hierarchies, petroglyphs providing a glimpse of ancient communication forms and motifs, heiau and burials exemplifying religious and supernatural beliefs, fishponds exhibiting a specialized subsistence technique, and a feature like the holua that represents royal recreational activity. Cordy et al., in their new report, suggest that further study of the Huehue Ranch operations that moved into Kaloko beginning in 1906 would be appropriate relative to location of buildings, walls, roads, and associated evidence of ranch operations. Basic data collection, mapping, and documentation of features should continue as new sites are found. An Archeological Base Map is needed as are available for the other two parks in this study. In addition, funding should be sought for a Park Administrative History documenting circumstances leading to the park's establishment, land acquisition procedures, and planning efforts to date. An Ethnographic Overview and Assessment and an ethnohistory should also be programmed. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chapter 9: Pu'uhonua o Honaunau Back to Contents Back to History |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |