Legends of Ghosts and Gods

LAU-KA-IEIE

Kakea (the white one) and Kaholo (the runner) were the children of the Valley. Their parents were the precipices which were sheer to the sea, and could only be passed by boats. They married, and Kaholo conceived. The husband said, "If a boy is born, I will name it; if a girl, you give the name." He went up to see his sister Pokahi, and asked her to go swiftly to see his wife. Pokahi's husband was Kaukini, a bird-catcher. He went out into the forest for some birds. Soon he came back and prepared them for cooking. Hot stones were put inside the birds and the birds were packed in calabashes, carefully covered over with wet leaves, which made steam inside so the birds were well cooked. Then they were brought to Kaholo for a feast. On their way they went down to Waipio Valley, coming to the foot of the precipice. Pokahi wanted some sea-moss and some shell-fish, so she told the two men to go on while she secured these things to take to Kaholo. She gathered the soft lipoa moss and went up to the waterfall, to Ulu (Kaholo's home). The baby was born, wrapped in the moss and thrown into the sea, making a shapeless bundle, but a kupua (sorcerer) saw that a child was there. The child was taken and washed clean in the soft lipoa, and cared for. All around were the signs of the birth of a chief. They named him Hiilawe, and from him the Waipio waterfall has its name, according to the saying, "Falling into mist is the water of Hiilawe." Pokahi took up her package in which she had brought the moss and shell-fish, but the moss was gone. Hina-ulu-ohia (Hina-the-growing-ohia-tree) was the sorcerer who took the child in the lipoa moss. She was the aumakua, or ancestor goddess, of the boat-builders. Pokahi dreamed that a beautiful woman appeared, her body covered with the leaves of ohia-trees. "I know that you have not had any child. I will now give you one. Awake, and go to the Waipio River; watch thirty days, then You will find a girl wrapped in soft moss. This shall be your adopted child. I will show you how to care for it. Your brother and his wife must not know. Your husband alone may know about this adopted girl." Pokahi and her husband went down at once to the mouth of the river, heard an infant cry in the midst of red-colored mist, and found a child wrapped in the fragrant moss. She wished to take it up, but was held back by magic powers. She saw an ohia-tree rising up from the water,--branches, leaves, and flowers,--and iiwi (birds) coming to pick the flowers. The red birds and red flowers were very beautiful. This tree was Hina. The birds began to sing, and quietly the tree sank down into the water and disappeared, the birds flying away to the west. Pokahi returned to her brother's house, going down to the sea every day, where she saw the human form of the child growing in the shelter of that red mist on the surface of the sea. At the end of the thirty days Pokahi told her friends and her husband that they must go back home. On their way they went to the river. She told her husband to look at the red mist, but he wanted to hurry on. As they approached their house, cooking-odors welcomed them, and they found plenty of food prepared outside. They saw something moving inside. The trees seemed to be walking as if with the feet of men. Steps were heard, and voices were calling for the people of the house. Kaukini prepared a lamp, and Pokahi in a vision saw the same fine tree which she had seen before. There was also a hala-tree with its beautiful yellow blossoms. As they looked they saw leaves of different kinds falling one after another, making in one place a soft fragrant bed. Then a woman and a man came with an infant. They were the god Ku and Hina his wife. They said to Pokahi and her husband, "We have accepted your sacrifices and have seen that you are childless, so now we have brought you this child to adopt." Then they disappeared among the trees of the forest, leaving the child, Lau-ka-ieie (leaf of the ieie vine). She was well cared for and grew up into a beautiful woman without fault or blemish. Her companions and servants were the birds and the flowers. Lau-ka-pali (leaf of the precipice) was one of her friends. One day she made whistles of ti leaves, and blew them. The Leaf-of-the-Morning-Glory saw that the young chiefess liked this, so she went out and found Pupu-kani-oi (the singing land-shell), whose home was on the leaves of the forest trees. Then she found another Pupu-hina-hina-ula (shell-beautiful with rainbow colors). In the night the shells sang, and their voices stole their way into the love of Lau-ka-ieie, so she gently sang with them. Nohu-ua-palai (a fern), one of the old residents of that place, went out into the forest, and, hearing the voices of the girl and the shells, came to the house. She chanted her name, but there was no reply. All was silent. At last, Pua-ohelo (the blossom of the ohelo), one of the flowers in the house, heard, and opening the door, invited her to come in and eat. Nohu-ua-palai went in and feasted with the girls. Lau-ka-ieie dreamed about Kawelona (the setting of the sun), at Lihue, a fine young man, the first-born of one of the high chiefs of Kauai. She told her kahu (guardian) all about her dream and the distant island. The kahu asked who should go to find the man of the dream. All the girl friends wanted to go. She told them to raise their hands and the one who had the longest fingers could go. This was Pupu-kani-oi (the singing shell). The leaf family all sobbed as they bade farewell to the shell. The shell said: "Oh, my leaf-sisters Laukoa [leaf of the koa-tree] and Lauanau [leaf of the paper-mulberry tree], arise, go with me on my journey! Oh, my shell-sisters of the blue sea, come to the beach, to the sand! Come and show me the path I am to go! Oh, Pupu-moka-lau [the land-shell clinging to the moki-hana leaf], come and look at me, for I am one of your family! Call all the shells to aid me in my journey! Come to me!" Then she summoned her brother, Makani-kau, chief of the winds, to waft them away in their wind bodies. They journeyed all around the island of Hawaii to find some man who would be like the man of the dream. They found no one there nor on any of the other islands up to Oahu, where the Singing Shell fell in love with a chief and turned from her journey, but Makani-kau went on to Kauai. Ma-eli-eli, the dragon woman of Heeia, tried to persuade him to stop, but on he went. She ran after him. Limaloa, the dragon of Laiewai, also tried to catch Makani-kau, but he was too swift. On the way to Kauai, Makani-kau saw some people in a boat chased by a big shark. He leaped on the boat and told them he would play with the shark and they could stay near but need not fear. Then he jumped into the sea. The shark turned over and opened its mouth to seize him; he climbed on it, caught its fins, and forced it to flee through the water. He drove it to the shore and made it fast among the rocks. It became the great shark stone, Koa-mano (warrior shark), at Haena. He leaped from the shark to land, the boat following. He saw the hill of "Fire-Throwing," a place where burning sticks were thrown over the precipices, a very beautiful sight at night. He leaped to the top of the hill in his shadow body. Far up on the hill was a vast number of iiwi (birds). Makani-kau went to them as they were flying toward Lehua. They only felt the force of the winds, for they could not see him or his real body. He saw that the birds were carrying a fine man as he drew near. This was the one Lau-ka-ieie desired for her husband. They carried this boy on their wings easily and gently over the hills and sea toward the sunset island, Lehua. There they slowly flew to earth. They were the bird guardians of Kawelona, and when they travelled from place to place they were under the direction of the bird-sorcerer, Kukala-a-ka-manu. Kawelona had dreamed of a beautiful girl who had visited him again and again, so he was prepared to meet Makani-kau. He told his parents and adopted guardians and bird-priests about his dreams and the beautiful girl he wanted to marry. Makani-kau met the winds of Niihau and Lehua, and at last was welcomed by the birds. He told Kawelona his mission, who prepared to go to Hawaii, asking how they should go. Makani-kau went to the seaside and called for his many bodies to come and give him the boat for the husband of their great sister Lau-ka-ieie. Thus he made known his mana, or spirit power, to Kawelona. He called on the great cloud-gods to send the long white cloud-boat, and it soon appeared. Kawelona entered the boat with fear, and in a few minutes lost sight of the island of Lehua and his bird guardians as he sailed out into the sea. Makani-kau dropped down by the side of a beautiful shell-boat, entered it, and stopped at Mana. There he took several girls and put them in a double canoe, or au-waa-olalua (spirit-boat). Meanwhile the sorcerer ruler of the birds agreed to find out where Kawelona was to satisfy the longing of his parents, whom he had left without showing them where he was going or what dangers he might meet. The sorcerer poured water into a calabash and threw in two lehua flowers, which floated on the water. Then he turned his eyes toward the sun and prayed: "Oh, great sun, to whom belongs the heavens, turn your eyes downward to look on the water in this calabash, and show us what you see therein! Look upon the beautiful young woman. She is not one from Kauai. There is no one more beautiful than she. Her home is under the glowing East, and a royal rainbow is around her. There are beautiful girls attending her." The sorcerer saw the sun-pictures in the water, and interpreted to the friends the journey of Kawelona, telling them it was a long, long way, and they must wait patiently many days for any word. In the signs he saw the boy in the cloud-boat, Makani-kau in his shell-boat, and the three girls in the spirit-boat. The girls were carried to Oahu, and there found the shell-girl, Pupu-kani-oi, left by Makani-kau on his way to Lehua. They took her with her husband and his sisters in the spirit-boat. There were nine in the company of travellers to Hawaii: Kawelona in his cloud-boat; two girls from Kauai; Kaiahe, a girl from Oahu; three from Molokai, one from Maui; and a girl called Lihau. Makani-kau himself was the leader; he had taken the girls away. On this journey he turned their boats to Kahoolawe to visit Ka-moho-alii, the ruler of the sharks. There Makani-kau appeared in his finest human body, and they all landed. Makani-kau took Kawelona from his cloud-boat, went inland, and placed him in the midst of the company, telling them he was the husband for Lau-ka-ieie. They were all made welcome by the ruler of the sharks. Ka-moho-alii called his sharks to bring food from all the islands over which they were placed as guardians; so they quickly brought prepared food, fish, flowers, leis, and gifts of all kinds. {p. 45} The company feasted and rested. Then Ka-moho-alii called his sharks to guard the travellers on their journey. Makani-kau went in his shell-boat, Kawelona in his cloud-boat, and they were all carried over the sea until they landed under the mountains of Hawaii. Makani-kau, in his wind body, carried the boats swiftly on their journey to Waipio. Lau-ka-ieie heard her brother's voice calling her from the sea. Hina answered. Makani-kau and Kawelona went up to Waimea to cross over to Lau-ka-ieie's house, but were taken by Hina to the top of Mauna Kea. Poliahu and Lilinoe saw the two fine young men and called to them, but Makani-kau passed by, without a word, to his own wonderful home in the caves of the mountains resting in the heart of mists and fogs, and placed all his travellers there. Makani-kau went down to the sea and called the sharks of Ka-moho-alii. They appeared m their human bodies in the valley of Waipio, leaving their shark bodies resting quietly in the sea. They feasted and danced near the ancient temple of Kahuku-welowelo, which was the place where the wonderful shell, Kiha-pu, was kept. Makani-kau put seven shells on the top of the precipice and they blew until sweet sounds floated Over all the land. Thus was the marriage of Lau-ka-ieie and Kawelona celebrated. All the shark people rested, soothed by the music. After the wedding they bade farewell and returned to Kahoolawe, going around the southern side of the island, for it was counted bad luck to turn back. They must go straight ahead all the way home. Makani-kau went to his sister's house, and met the girls and Lau-ka-ieie. He told her that his house was full of strangers, as the people of the different kupua bodies had assembled to celebrate the wedding. These were the kupua people of the Hawaiian Islands. The eepa people were more like fairies and gnomes, and were usually somewhat deformed. The kupuas may be classified as follows:

After the marriage, Pupu-kani-oi (the singing shell) and her husband entered the shell-boat, and started back to Molokai. On their way they heard sweet bird voices. Makani-kau had a feather house covered with rainbow colors. Later he went to Kauai, and brought back the adopted parents of Kawelona to dwell on Hawaii, where Lau-ka-ieie lived happily with her husband. Hiilawe became very ill, and called his brother Makani-kau and his sister Lau-ka-ieie to come near and listen. He told them that he was going to die, and they must bury him where he could always see the eyes of the people, and then he would change his body into a wonderful new body. The beautiful girl took his malo and leis and placed them along the sides of the valley, where they became trees and clinging vines, and Hina made him live again; so Hiilawe became an aumakua of the waterfalls. Makani-kau took the body in his hands and carried it in the thunder and lightning, burying it on the brow of the highest precipice of the valley. Then his body was changed into a stone, which has been lying there for centuries; but his ghost was made by Hina into a kupua, so that he could always appear as the wonderful misty falls of Waipio, looking into the eyes of his people. After many years had passed Hina assumed permanently the shape of the beautiful ohia-tree, making her home in the forest around the volcanoes of Hawaii. She still had magic power, and was worshipped under the name Hina-ula-ohia. Makani-kau watched over Lau-ka-ieie, and when the time came for her to lay aside her human body she came to him as a slender, graceful woman, covered with leaves, her eyes blazing like fire. Makani-kau said: "You are a vine; you cannot stand alone. I will carry you into the forest and place you by the side of Hina. You are the ieie vine. Climb trees! Twine your long leaves around them! Let your blazing red flowers shine between the leaves like eyes of fire! Give your beauty to all the ohia-trees of the forest! " Carried hither and thither by Makani-kau (great wind), and dropped by the side of splendid tall trees, the ieie vine has for centuries been one of the most graceful tree ornaments in all the forest life of the Hawaiian Islands. Makani-kau in his spirit form blew the golden clouds of the islands into the light of the sun, so that the Rainbow Maiden, Anuenue, might lend her garments to all her friends of the ancient days. Back to Contents

KAUHUHU, THE SHARK-GOD OF MOLOKAIThe story of the shark-god Kauhuhu has been told under the legend of "Aikanaka the (Man-eater)," which was the ancient name of the little harbor Pukoo, which lies at the entrance to one of the beautiful valleys of the island of Molokai. The better way is to take the legend as revealing the great man-eater in one of his most kindly aspects. The shark-god appears as the friend of a priest who is seeking revenge for the destruction of his children. Kamalo was the name of the priest. His heiau, or temple, was at Kaluaaha, a village which faced the channel between the islands of Molokai and Maui. Across the channel the rugged red-brown slopes of the mountain Eeke were lost in the masses of clouds which continually hung around its sharp peaks. The two boys of the priest delighted in the glorious revelations of sunrise and sunset tossed in shattered fragments of cloud color, and rejoiced in the reflected tints which danced to them over the swift channel-currents. It is no wonder that the courage of sky and sea entered into the hearts of the boys, and that many deeds of daring were done by them. They were taught many of the secrets of the temple by their father, but were warned that certain things were sacred to the gods and must not be touched. The high chief, or alii, of that part of the island had a temple a short distance from Kaluaaha, in the valley of the harbor which was called Aikanaka. The name of this chief was Kupa. The chiefs always had a house built within the temple walls as their own residence, to which they could retire at certain seasons of the year. Kupa had two remarkable drums which he kept in his house at the heiau. His skill in beating his drums was so great that they could reveal his thoughts to the waiting priests.

One day Kupa sailed far away over the sea to his favorite fishing-grounds. Meanwhile the boys were tempted to go to Kupa's heiau and try the wonderful drums. The valley of the little harbor Aikanaka bore the musical name Mapulehu. Along the beach and over the ridge hastened the two sons of Kamalo. Quickly they entered the heiau, found the high chief's house, took out his drums and began to beat upon them. Some of the people heard the familiar tones of the drums. They dared not enter the sacred doors of the heiau, but watched until the boys became weary of their sport and returned home. When Kupa returned they told him how the boys had beaten upon his sacred drums. Kupa was very angry, and ordered his mu, or temple sacrifice seekers, to kill the boys and bring their bodies to the heiau to be placed on the altar. When the priest Kamalo heard of the death of his sons, in bitterness of heart he sought revenge. His own power was not great enough to cope with his high chief; therefore he sought the aid of the seers and prophets of highest repute throughout Molokai. But they feared Kupa the chief, and could not aid him, and therefore sent him on to another kaula, or prophet, or sent him back to consult some one the other side of his home. All this time he carried with him fitting presents and sacrifices, by which he hoped to gain the assistance of the gods through their priests. At last he came to the steep precipice which overlooks Kalaupapa and Kalawao, the present home of the lepers. At the foot of this precipice was a heiau, in which the great shark-god was worshipped. Down the sides of the precipice he climbed and at last found the priest of the shark-god. The priest refused to give assistance, but directed him to go to a great cave in the bold cliffs south of Kalawao. The name of the cave was Anao-puhi, the cave of the eel. Here dwelt the great shark-god Kauhuhu and his guardians or watchers, Waka and Mo-o, the great dragons or reptiles of Polynesian legends. These dragons were mighty warriors in the defence of the shark-god, and were his kahus, or caretakers, while he slept, or when his cave needed watching during his absence. Kamalo, tired and discouraged, plodded along through the rough lava fragments piled around the entrance to the cave. He bore across his shoulders a black pig, which he had carried many miles as an offering to whatever power he could find to aid him. As he came near to the cave the watchmen saw him and said: "E, here comes a man, food for the great [shark] Mano. Fish for Kauhuhu." But Kamalo came nearer and for some reason aroused sympathy in the dragons. "E hele! E hele!" they cried to him. "Away, away! It is death to you. Here's the tabu place." "Death it may be--life it may be. Give me revenge for my sons--and I have no care for myself." Then the watchmen asked about his trouble and he told them how the chief Kupa had slain his sons as a punishment for beating the drums. Then he narrated the story of his wanderings all over Molokai, seeking for some power strong enough to overcome Kupa. At last he had come to the shark-god-as the final possibility of aid. If Kauhuhu failed him, he was ready to die; indeed he had no wish to live. The mo-o assured him of their kindly feelings, and told him that it was a very good thing that Kauhuhu was away fishing, for if he had been home there would have been no way for him to go before the god without suffering immediate death. There would have been not even an instant for explanations. Yet they ran a very great risk in aiding him, for they must conceal him until the way was opened by the favors of the great gods. If he should be discovered and eaten before gaining the aid of the shark-god, they, too, must die with him. They decided that they would hide him in the rubbish pile of taro peelings which had been thrown on one side when they had pounded taro. Here he must lie in perfect silence until the way was made plain for him to act. They told him to watch for the coming of eight great surf waves rolling in from the sea, and then wait in his place of concealment for some opportunity to speak to the god because he would come in the last great wave. Soon the surf began to roll in and break against the cliffs. Higher and higher rose the waves until the eighth reared far above the waters. and met the winds from the shore which whipped the curling crest into a shower of spray. It raced along the water and beat far up into. the cave, breaking into foam, out of which the shark-god emerged. At once he took his human form and walked around the cave. As he passed the rubbish heap he cried out: "A man is here. I smell him." The dragons earnestly denied that any one was there, but the shark-god said, "There is surely a man in this cave. If I find him, dead men you are. If I find him not, you shall live." Then Kauhuhu looked along the walls of the cave and into all the hiding-places, but could not find him. He called with a loud voice, but only the echoes answered, like the voices of ghosts. After a thorough search he was turning away to attend to other matters when Kamalo's pig squealed. Then the giant shark-god leaped to the pile of taro leavings and thrust them apart. There lay Kamalo and the black pig which had been brought for sacrifice.

Kauhuhu instantly caught Kamalo and lifted him from the rubbish up toward his great mouth. Now the head and shoulders are in Kauhuhu's mouth. So quickly has this been done that Kamalo has had no time to think. Kamalo speaks quickly as the teeth are coming down upon him. "E Kauhuhu, listen to me. Hear my prayer. Then perhaps eat me." The shark-god is astonished and does not bite. He takes Kamalo from his mouth and says: "Well for you that you spoke quickly. Perhaps you have a good thought. Speak." Then Kamalo told about his sons and their death at the hands of the executioners of the great chief, and that no one dared avenge him, but that all the prophets of the different gods had sent him from one place to another but could give him no aid. Sure now was he that Kauhuhu alone could give him aid. Pity came to the shark-god as it had come to his dragon watchers when they saw the sad condition of Kamalo. All this time Kamalo had held the hog which he had carried with him for sacrifice. This he now offered to the shark-god. Kauhuhu, pleased and compassionate, accepted the offering, and said: "E Kamalo. If you had come for any other purpose I would eat you, but your cause is sacred. I will stand as your kahu, your guardian, and sorely punish the high chief Kupa." Then he told Kamalo to go to the heiau of the priest who told him to see the shark-god, take this priest on his shoulders, carry him over the steep precipices to his own heiau at Kaluaaha, and there live with him as a fellow-priest. They were to build a tabu fence around the heiau and put up the sacred tabu staffs of white tapa cloth. They must collect black pigs by the four hundred, red fish by the four hundred, and white chickens by the four hundred. Then they were to wait patiently for the coming of Kauhuhu. It was to be a strange coming. On the island Lanai, far to the west of the Maui channel, they should see a small cloud, white as snow, increasing until it covered the little island. Then that cloud would cross the channel against the wind and climb the mountains of Molokai until it rested on the highest peaks over the valley where Kupa had his temple. "At that time," said Kauhuhu, "a great rainbow will span the valley. I shall be in the care of that rainbow, and you may clearly understand that I am there and will speedily punish the man who has injured you. Remember that because you came to me for this sacred cause, therefore I have spared you, the only man who has ever stood in the presence of the shark-god and escaped alive." Swiftly did Kamalo go up and down precipices and along the rough hard ways to the heiau of the priest of the shark-god. Gladly did he carry him up from Kalaupapa to the mountain-ridge above. Quickly did he carry him to his home and there provide for him while he gathered together the black pigs, the red fish, and the white chickens within the sacred enclosure he had built. Here he brought his family, those who had the nearest and strongest claims upon him. When his work was done, his eyes burned with watching the clouds of the little western island Lanai. Ah, the days passed by so slowly! The weeks and the months came, so the legends say, and still Kamalo waited in patience. At last one day a white cloud appeared. It was unlike all the other white clouds he had anxiously watched during the dreary months. Over the channel it came. it spread over the hillsides and climbed the mountains and rested at the head of the valley belonging to Kupa. Then the watchers saw the glorious rainbow and knew that Kauhuhu had come according to his word. The storm arose at the head of the valley. The winds struggled into a furious gale. The clouds gathered in heavy black masses, dark as midnight, and were pierced through with terrific flashes of lightning. The rain fell in floods, sweeping the hillside down into the valley, and rolling all that was below onward in a resistless mass toward the ocean. Down came the torrent upon the heiau belonging to Kupa, tearing its walls into fragments and washing Kupa and his people into the harbor at the mouth of the valley. Here the shark-god had gathered his people. Sharks filled the bay and feasted upon Kupa and his followers until the waters ran red and all were destroyed. Hence came the legendary name for that little harbor--Aikanaka, the place for man-eaters. It is said in the legends that "when great clouds gather on the mountains and a rainbow spans the valley, look out for furious storms of wind and rain which come suddenly, sweeping down the valley." It also said in the legends that this strange storm which came in such awful power upon Kupa spread out over the adjoining lowlands, carrying great destruction everywhere, but it paused at the tabu staff of Kamalo, and rushed on either side of the sacred fence, not daring to touch any one who dwelt therein. Therefore Kamalo and his people were spared. The legend has been called "Aikanaka" because of the feast of the sharks on the human flesh swept down into that harbor by the storm, but it seems more fitting to name the story after the shark-god Kauhuhu, who sent mighty storms and wrought great destruction. Back to Contents

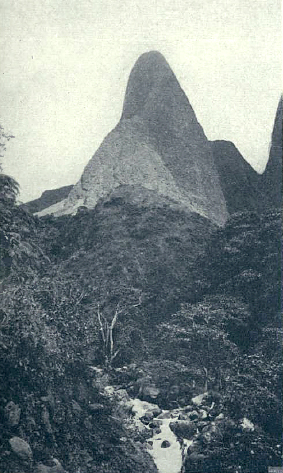

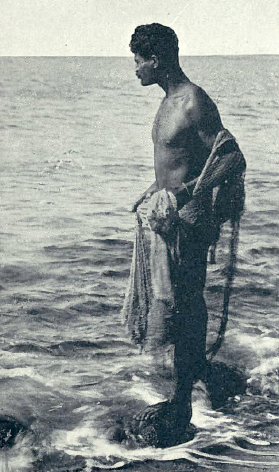

THE SHARK-MAN OF WAIPIO VALLEYThis is a story of Waipio Valley, the most beautiful of all the valleys of the Hawaiian Islands, and one of the most secluded. It is now, as it has always been, very difficult of access. The walls are a sheer descent of over a thousand feet. In ancient times a narrow path slanted along the face of the bluffs wherever foothold could be found. In these later days the path has been enlarged, and horse and rider can descend into the valley's depths. In the upper end of the valley is a long silver ribbon water falling fifteen hundred feet from the brow of a precipice over which a mountain torrent swiftly hurls itself to the fertile valley below. Other falls show the convergence of several mountain streams to the ocean outlet offered by the broad plains of Waipio. Here in the long ago high chiefs dwelt and sacred temples were built. From Waipio Valley Moikeha and Laa-Mai-Kahiki sailed away on their famous voyages to distant foreign lands. In this valley dwelt the priest who in the times of Maui was said to have the winds of heaven concealed in his calabash. Raising the cover a little, he sent gentle breezes in the direction of the opening. Severe storms and hurricanes were granted by swiftly opening the cover widely and letting a chaotic mass of fierce winds escape. The stories of magical powers of bird and fish as well as of the strange deeds of powerful men are almost innumerable. Not the least of the history-myths of Waipio Valley is the story of Nanaue, the shark-man, who was one of the cannibals of the ancient time. Ka-moho-alii was the king of all the sharks which frequent Hawaiian waters. When he chose to appear as a man he was always a chief of dignified, majestic appearance. One day, while swimming back and forth just beneath the surface of the waters at the mouth of the valley, he saw an exceedingly beautiful woman coming to bathe in the white surf. That night Ka-moho-alii came to the beach black with lava sand, crawled out of the water, and put on the form of a man. As a mighty chief he walked through the valley and mingled with the people. For days he entered into their sports and pastimes and partook of their bounty, always looking for the beautiful woman whom he had seen bathing in the surf. When he found her he came to her and won her to be his wife. Kalei was the name of the woman who married the strange chief. When the time came for a child to be born to them, Ka-moho-alii charged Kalei to keep careful watch of it and guard its body continually from being seen of men, and never allow the child to eat the flesh of any animal. Then he disappeared, never permitting Kalei to have the least suspicion that he was the king of the sharks. When the child was born, Kalei gave to him the name "Nanaue." She was exceedingly surprised to find an opening in his back. As the child grew to manhood the opening developed into a large shark-mouth in rows of fierce sharp teeth. From infancy to manhood Kalei protected Nanaue by keeping his back covered with a fine kapa cloak. She was full of fear as she saw Nanaue plunge into the water and become a shark. The mouth on his back opened for any kind of prey. But she kept the terrible birthmark of her son a secret hidden in the depths of her own heart. For years she prepared for him the common articles of food, always shielding him from the temptation to eat meat. But when he became a man his grandfather took him to the men's eating-house, where his mother could no longer protect him. Meats of all varieties were given to him in great abundance, yet he always wanted more. His appetite was insatiable. While under his mother's care he had been taken to the pool of water into which the great Waipio Falls poured its cascade of water. There he bathed, and, changing himself into a shark, caught the small fish which were playing around him. His mother was always watching him to give an alarm if any of the people came near to the bathing-place. As he became a man he avoided his companion, in all bathing and fishing. He went away by himself. When the people were out in the deep sea bathing or fishing, suddenly a fierce shark would appear in their midst, biting and tearing their limbs and dragging them down in the deep water. Many of the people disappeared secretly, and great terror filled the homes of Waipio. Nanaue's mother alone was certain that hie was the cause of the trouble. He was becoming very bold in his depredations. Sometimes he would ask when his friends were going out in the sea; then he would go to a place at some distance, leap into the sea, and swiftly dash to intercept the return of his friends to the shore. Perhaps he would allay suspicion by appearing as a man and challenge to a swimming-race. Diving suddenly, he would in an instant become a shark and destroy his fellow-swimmer. The people felt that he had some peculiar power, and feared him. One day, when their high chief had called all the men of the valley to prepare the taro patches for their future supply of food, a fellow-workman standing by the side of Nanaue tore his kapa cape from his shoulders. The men behind cried out, "See the great shark-mouth!" All the people came running together, shouting, "A shark-man!" "A shark-man!" Nanaue became very angry and snapped his shark-teeth together. Then with bitter rage he attacked those standing near him. He seized one by the arm and bit it in two. He tore the flesh of another in ragged gashes. Biting and snapping from side to side he ran toward the sea. The crowd of natives surrounded him and blocked his way. He was thrown down and tied. The mystery had now passed from the valley. The people knew the cause of the troubles through which they had been passing, and all crowded around to see this wonderful thing, part man and part shark. The high chief ordered their largest oven to be prepared, that Nanaue might be placed therein and burned alive. The deep pit was quickly cleaned out by many willing hands, and, with much noise and rejoicing, fire was placed within and the stones for heating were put in above the fire. "We are ready for the shark-man," was the cry. During the confusion Nanaue quietly made his plans to escape. Suddenly changing himself to a shark, the cords which bound him fell off and he rolled into one of the rivers which flowed from the falls in the upper part of the valley. None of the people dared to spring into the water for a hand-to-hand fight with the monster. They ran along the bank, throwing stones at Nanaue and bruising him. They called for spears that they might kill him, but he made a swift rush to the sea and swam away, never again to return to Waipio Valley. Apparently Nanaue could not live long in the ocean. The story says that he swam over to the island of Maui and landed near the village Hana. There he dwelt for some time, and married a chiefess. Meanwhile he secretly killed and ate some of the people. At last his appetite for human flesh made him so bold that he caught a beautiful young girl and carried her out into the deep waters. There he changed himself into a shark and ate her body in the sight of the people. The Hawaiians became very angry. They launched their canoes, and, throwing in all kinds of weapons, pushed out to kill their enemy. But he swam swiftly away, passing around the island until at last he landed on Molokai.

Again he joined himself to the people, and again one by one those who went bathing and fishing disappeared. The priests (kahunas) of the people at last heard from their fellow-priests of the island of Maui that there was a dangerous shark-man roaming through the islands. They sent warning to the people, urging all trusty fishermen to keep strict watch. At last they saw Nanaue change himself into a great fish. The fishermen waged a fierce battle against him. They entangled him in their nets, they pierced him with spears and struck him with clubs until the waters were red with his blood. They called on the gods of the sea to aid them. They uttered prayers and incantations. Soon Nanaue lost strength and could not throw off the ropes which were tied around him, nor could he break the nets in which he was entangled. The fishermen drew him to the shore, and the people dragged the great shark body up the hill Puu-mano. Then they cut the body into small pieces and burned them in a great oven. Thus died Nanaue, whose cannibal life was best explained by giving to him in mythology the awful appetite of an insatiable man-eating shark. Back to Contents

THE STRANGE BANANA SKINKukali, according to the folk-lore of Hawaii, was born at Kalapana, the most southerly point of the largest island of the Hawaiian group. Kukali lived hundreds of years ago in the days of the migrations of Polynesians from one group of islands to another throughout the length and breadth of the great Pacific Ocean. He visited strange lands, now known under the general name, Kahiki, or Tahiti. Here he killed the great bird Halulu, found the deep bottomless pit in which was a pool of the fabled water of life, married the sister of Halulu, and returned to his old home. All this he accomplished through the wonderful power of a banana skin. Kukali's father was a priest, or kahuna, of great wisdom and ability, who taught his children how to exercise strange and magical powers. To Kukali he gave a banana with the impressive charge to preserve the skin whenever he ate the fruit, and be careful that it was always under his control. He taught Kukali the wisdom of the makers of canoes and also how to select the fine-grained lava for stone knives and hatchets,and fashion the blade to the best shape. He instructed the young man in the prayers and incantations of greatest efficacy and showed him charms which would be more powerful than any charms his enemies might use in attempting to destroy him, and taught him those omens which were too powerful to be overcome. Thus Kukali became a wizard, having great confidence in his ability to meet the craft of the wise men of distant islands. Kukali went inland through the forests and up the mountains, carrying no food save the banana which his father had given him. Hunger came, and he carefully stripped back the skin and ate the banana, folding the skin once more together. In a little while the skin was filled with fruit. Again and again he ate, and as his hunger was satisfied the fruit always again filled the skin, which he was careful never to throw away or lose. The fever of sea-roving was in the blood of the Hawaiian people in those days, and Kukali's heart burned within him with the desire to visit the far-away lands about which other men told marvelous tales and from which came strangers like to the Hawaiians in many ways. After a while he went to the forests and selected trees approved by the omens, and with many prayers fashioned a great canoe in which to embark upon his journey. The story is not toldof the days passed on the great stretches of water as he sailed on and on, guided by the sun in the day and the stars in the night, until he came to the strange lands about which he had dreamed for years. His canoe was drawn up on the shore and he lay down for rest. Before falling asleep he secreted his magic banana in his malo, or loincloth, and then gave himself to deep slumber. His rest was troubled with strange dreams, but his weariness was great and his eves heavy, and he could not arouse himself to meet the dangers which were swiftly surrounding him. A great bird which lived on human flesh was the god of the land to which he had come. The name of the bird was Halulu. Each feather of its wings was provided with talons and seemed to be endowed with human powers. Nothing like this bird was ever known or seen in the beautiful Hawaiian Islands. But here in the mysterious foreign land it had its deep valley, walled in like the valley of the Arabian Nights, over which the great bird hovered looking into the depths for food. A strong wind always attended the coming of Halulu when he sought the valley for his victims. Kukali was lifted on the wings of the bird-god and carried to this hole and quietly laid on the ground to finish his hour of deep sleep. When Kukali awoke he found himself in the shut-in valley with many companions who had been captured by the great bird and placed in this prison hole. They had been without food and were very weak. Now and then one of the number would lie down to die. Halulu, the bird-god, would perch on a tree which grew on the edge of the precipice and let down its wing to sweep across the floor of the valley and pick up the victims lying on the ground. Those who were strong could escape the feathers as they brushed over the bottom and hide in the crevices in the walls, but day by day the weakest of the prisoners were lifted out and prepared for Halulu's feast. Kukali pitied the helpless state of his fellow-prisoners and prepared his best incantations and prayers to help him overcome the great bird. He took his wonderful banana and fed all the people until they were very strong. He taught them how to seek stones best fitted for the manufacture of knives and hatchets. Then for days they worked until they were all well armed with sharp stone weapons. While Kukali and his fellow-prisoners were making preparation for the final struggle, the bird-god had often come to his perch and put his wing down into the valley, brushing the feathers back and forth to catch his prey. Frequently the search was fruitless. At last he became very impatient, and sent his strongest feathers along the precipitous walls, seeking for victims. Kukali and his companions then ran out from their hiding-places and fought the strong feathers, cutting them off and chopping them into small pieces. Halulu cried out with pain and anger, and sent feather after feather into the prison. Soon one wing was entirely destroyed. Then the other wing was broken to pieces and the bird-god in his insane wrath put down a strong leg armed with great talons. Kukali uttered mighty invocations and prepared sacred charms for the protection of his friends. After a fierce battle they cut off the leg and destroyed the talons. Then came the struggle with the remaining leg and claws, but Kukali's friends had become very bold. They fearlessly gathered around this enemy, hacking and pulling until the bird-god, screaming with pain, fell into the pit among the prisoners, who quickly cut the body into fragments. The prisoners made steps in the walls, and by the aid of vines climbed out of their prison. When they had fully escaped, they gathered great piles of branches and trunks of trees and threw them into the prison until the body of the bird-god was covered. Fire was thrown down and Halulu was burned to ashes. Thus Kukali taught by his charms that Halulu could be completely destroyed. But two of the breast feathers of the burning Halulu flew away to his sister, who lived in a great hole which had no bottom. The name of this sister was Namakaeha. She belonged to the family of Pele, the goddess of volcanic fires, who had journeyed to Hawaii and taken up her home in the crater of the volcano Kilauea. Namakaeha smelled smoke on the feathers which came to her, and knew that her brother was dead. She also knew that he could have been conquered, only by one possessing great magical powers. So she called to his people: "Who is the great kupua [wizard] who has killed my brother? Oh, my people, keep careful watch." Kukali was exploring all parts of the strange land in which he had already found marvelous adventures. By and by he came to the great pit in which Namakaeha lived. He could not see the bottom, so he told his companions he was going down to see what mysteries were concealed in this hole without a bottom. They made a rope of the hau tree bark. Fastening one end around his body he ordered his friends to let him down. Uttering prayers and incantations he went down and down until, owing to counter incantations of Namakaeha's priests, who had been watching, the rope broke and he fell. Down he went swiftly, but, remembering the prayer which a falling man must use to keep him from injury, he cried, "O Ku! guard my life!" In the ancient Hawaiian mythology there was frequent mention of "the water of life." Sometimes the sick bathed in it and were healed. Sometimes it was sprinkled upon the unconscious, bringing them back to life. Kukali's incantation was of great power, for it threw him into a pool of the water of life and he was saved. One of the kahunas (priests) caring for Namakaeha was a very great wizard. He saw the wonderful preservation of Kukali and became his friend. He warned Kukali against eating anything that was ripe, because it would be poison, and even the most powerful charms could not save him. Kukali thanked him and went out among the people. He had carefully preserved his wonderful banana skin, and was able to eat apparently ripe fruit and yet be perfectly safe. The kahunas of Namakaeha tried to overcome him and destroy him, but he conquered them, killed those who were bad, and entered into friendship with those who were good. At last he came to the place where the great chiefess dwelt. Here he was tested in many ways. He accepted the fruits offered him, but always ate the food in his magic banana. Thus he preserved his strength and conquered even the chiefess and married her. After living with her for a time he began to long for his old home in Hawaii. Then he persuaded her to do as her relative Pele had already done, and the family, taking their large canoe, sailed away to Hawaii, their future home. Back to Contents

THE OLD MAN OF THE MOUNTAINThis is not a Hawaiian legend. It was written to show the superstitions of the Hawaiians, and in that respect it is accurate and worthy of preservation. FAR away in New England one of the rugged mountain-sides has for many years been marked with the profile of a grand face. A noble brow, deep-set eyes, close-shut lips, Roman nose, and chin standing in full relief against a clear sky, made a landmark renowned throughout the country. The story is told of a boy who lived in the valley from which the face of the Old Man of the Mountain could be most clearly seen. As the years passed, the boy grew into a man of sterling character. When at last death came and the casket opened to receive the body of an old man, universally revered, the friends saw the likeness to the stone features of the Old Man of the Mountain, and recognized the source of the inspiration which had made one life useful and honored. Near Honolulu, just beyond one of the great sugar plantations, is a ledge of lava deposited centuries ago. The lava was piled up into mountains, now dissolved into slopes of the richest sugar-land in the world. And yet sometimes the hard lava, refusing to disintegrate, thrusts itself out from the hillsides in ledges of grotesque form. On one of' these ancient lava ridges was the outline of an old man's face, to which the Hawaiians have given the name, "The Old Man of the Mountain." The laborers on the sugar-plantations, the passengers on the railroad trains, and the natives who still cling to their scattered homes sometimes have looked with superstitious awe upon the face made without hands. In the days gone by they have called it the "Akua-pohaku" (the stone god). Shall we hear the story of Kamakau, who at some time in the indefinite past dwelt in the shadow of the stone face? Kamakau means "the afraid." His name came to him as a child. He was a shrinking, sensitive, imaginative little fellow. He was surrounded by influences which turned his imagination into the paths of most unwholesome superstition. But beyond the beliefs of most of his fellows, in his own nature he was keenly appreciative of mysterious things. There was a spirit voice in every wind rustling the tops of the trees. Spirit faces appeared in unnumbered caricatures of human outline whenever he lay on the grass and watched the sunlight sift between the leaves. Everything he looked upon or heard assumed some curious form of life. The clouds were most mysterious of all, for they so frequently piled up mass upon mass of grandeur, in such luxurious magnificence and such prodigal display of color, that his power of thought lost itself in his almost daily dream of some time wandering in the shadow valleys of the precipitous mountains of heaven. Here he saw also strangely symmetrical forms of man and bird and fish. Sometimes cloud forests outlined themselves against the blue sky, and then again at times separated by months and even years, the lights of the volcano-goddess, Pele, glorified her path as she wandered in the spirit land, flashing from cloud-peak to cloud-peak, while the thunder voices of the great gods rolled in mighty volumes of terrific impressiveness. Even in the night Kamakau felt that the innumerable stars were the eyes of the aumakuas (the spirits of the ancestors). It was not strange that such a child should continually think that he saw spirit forms which were invisible to his companions. It is no wonder that he fancied he heard voices of the menehunes (fairies), which his companions could never understand. As he shrunk from places where it seemed to him the spirits dwelt, his companions called him "Kamakau," "the afraid." When he grew older he necessarily became keenly alive to all objects of Hawaiian superstition. He never could escape the overwhelming presence of the thousand and more gods which were supposed to inhabit the Hawaiian land and sea. The omens drawn from sacrifices, the voices from the bamboo dwelling-places of the oracles, the chants of the prophets, and powers of praying to death he accepted with unquestioning faith. Two men were hunting in the forests of the mountains of Oahu. Tired with the long chase after the oo, the bird with the rare yellow feathers from which the feather cloaks of the highest chiefs were made, they laid aside spears and snares and lay down for a rest. "I want the valley of the stone god," said one: "its fertile fields would make just the increase needed for my retainers, and the 'moi,' the king, would give me the land if Kamakau were out of the way." "Are there any other members of his family, O Inaina, who could resist your claim? " " No, my friend Kokua. He is the only important chief in the valley." "Pray him to death," was Kokua's sententious advice. "Good; I'll do it," said Inaina: "he is one who can easily be prayed to death. 'The Afraid' will soon die." "If you will give me the small fish-pond nearest my own coral fish-walls I will be your messenger," said Kokua. "Ah, that also is good," replied Inaina, after a moment's thought. "I will give you the small pond, and you must give the small thoughts, the hints, to his friends that powerful priests are praying Kamakau to death. All this must be very mysterious. No name can be mentioned, and you and I must be Kamakau's good friends." It must be remembered that land tenure in ancient Hawaii was almost the same as that of the European feudal system. Occupancy depended upon the will of the high chief. He gave or took away at his own pleasure. The under-chiefs held the land as if it belonged to them, and were seldom troubled as long as the wishes of the high chief, or king, were carried out. Inaina felt secure in the use of his present property, and believed that he could easily find favor and obtain the land held by the Kamakau family if Kamakau himself could be removed. Without much further conference the two hunters returned to their homes. Inaina at once sought his family priest and stated his wish to have Kamakau prayed to death. They decided that the first step should be taken that night. It was absolutely necessary that something which had been a part of the body of Kamakau should be obtained. The priest appointed his confidential hunter of sacrifices to undertake this task. This servant of the temple was usually sent out to find human sacrifices to be slain and offered before the great gods on special occasions. As the darkness came on he crept near the grass house of Kamakau and watched for an opportunity of seizing what he wanted. The two most desired things in the art of praying to death were either a lock of hair from the head of the victim or a part of the spittle, usually well guarded by the trusted retainers who had charge of the spittoon. It chanced to be "Awa night" for Kamakau, and the chief, having drunk heavily of the drug, had thrown himself on a mat and rolled near the grass walls. With great ingenuity the hunter of sacrifices located the chief and worked a hole through the thatch. Then with his sharp bone knife he sawed off a large lock of Kamakau's hair. When this was done he was about to creep away, but a native came near. Instantly grunting like a hog, he worked his way into the darkness. He saw outlined against the sky in the hands of the native the chief's spittoon. In a moment the hunter of sacrifices saw his opportunity. His past training in lying in wait and capturing men for sacrifice stood him in good stead at this time. The unsuspecting spittoon carrier was seized by the throat and quickly strangled. The spittoon in falling from the retainer's hand had not been overturned. Exultant at his success, the hunter of sacrifices sped away in the darkness and placed his trophies in the hands of the priest. The next morning there was a great outcry in Kamakau's village. The dead body was found as soon as dawn crept over the valley, and the hand-polished family calabash was completely lost. When the people went to Kamakau's house with the report of the death of his retainer, they soon saw that the head of their chief had been dishonored. A great feeling of fear took possession of the village. Kamakau's priest hurried to the village temple to utter prayers and incantations against the enemy who had committed such an outrage. Kokua soon heard the news and came to comfort his neighbor. After the greeting, "Auwe! auwe! " (Alas! alas!) Kokua said: " This is surely praying to death, and the gods have already given you over into the hands of your enemy. You will die. Very soon you will die." Soon Inaina and other chiefs came with their retainers. Among high and low the terrible statement was whispered: "Kamakau is being prayed to death, and no man knows his enemy." Many a strong man has gone to a bed of continued illness, and some have crossed the dark valley into the land of death, even in these days of enlightened civilization, simply frightened into the illness or death by the strong statements of friends and acquaintances. Such is the make-up of the minds of men that they are easily affected by the mysterious suggestions of others. It is purely a matter of mind-murder. It is no wonder that in the days of the long ago Kamakau, moved by the terror of his friends and horrible suggestions of his two enemies, soon felt a great weakness conquering him. His natural disposition, his habit of seeing and hearing gods and spirits in everything around him, made it easy for him to yield to the belief that he was being prayed to death. His strength left him. He could take no food. A strange paralysis seemed to take possession of him. Mind and body were almost benumbed. He was really in the hands of unconscious mesmerists, who were putting him into a magnetic sleep, from which he was never expected to awake. It is a question to be answered only when all earthly problems have been solved. How many of the people prayed to death have really been dissected and prepared for burial while at first under mesmeric influences! The people gathered around Karnakau's thatched house. They thought that he would surely die before the next morning dawned. Inaina and Kokua were lying on the grass under the shade of a great candlenut-tree, quietly talking about the speedy success of their undertaking. A little girl was playing near them. It was Kamakau's little Aloha. This was all the name so far given to her. She was "My Aloha," "my dear one," to both father and mother. She heard a word uttered incautiously. Inaina had spoken with the accent of success and his voice was louder than he thought. He said, "We have great strength if we kill Kamakau." The child fled to her father. She found him in the half -unconscious state already described. She shook him. She called to him. She pulled his hands, and covered his face with kisses. Her tears poured over his hot, dry skin. Kamakau was aroused by the shock. He sat up, forgetting all the expectation of death. Out through the doorway he glanced toward the west. The sinking sun was sending its most glorious beams into the grand clouds, while just beneath, reflecting the glory, lay the Old Man of the Mountain. The stone face was magnificent in its setting. The unruffled brow, the never-closing eyes, the firm lips, stood out in bold relief against the glory which was over and beyond them. Kamakau caught the inspiration. It seemed to his vivid imagination as if ten thousand good spirits were gathered in the heavens to fight for him. He leaped to his feet, strength came back into the wearied muscles, a new will-power took possession of him, and he cried: "I will not die! I will not die! The stone god is more powerful than the priests who pray to death!" His will had broken away from its chains, and, unfettered from all fear, Kamakau went forth to greet the wondering people and take up again the position of influence held among the chiefs of Oahu. The lesson is still needed in these beautiful ocean-bound islands that praying to death means either the use of poison or the attempt to terrify the victim by strong mental forces enslaving the will. In either case the aroused will is powerful in both resistance and watchfulness. Back to Contents

HAWAIIAN GHOST TESTINGManoa Valley for centuries has been to the Hawaiians the royal palace of rainbows. The mountains at the head of the valley were gods whose children were the divine wind and rain from whom was born the beautiful rainbow-maiden who plays in and around the valley day and night whenever misty showers are touched by sunlight or moonlight. The natives of the valley usually give her the name of Kahalaopuna, or The Hala of Puna. Sometimes, however, they call her Kaikawahine Anuenue, or The Rainbow Maiden. The rainbow, the anuenue, marks the continuation of the legendary life of Kahala. The legend of Kahala is worthy of record in itself, but connected with the story is a very interesting account of an attempt to discover and capture ghosts according to the methods supposed to be effective by the Hawaiian witch doctors or priests of the long, long ago. The legends say that the rainbow-maiden had two lovers, one from Waikiki, and one from Kamoiliili, half-way between Manoa and Waikiki. Both wanted the beautiful arch to rest over their homes, and the maiden, the descendant of the gods, to dwell therein. Kauhi, the Waikiki chief, was of the family of Mohoalii, the shark-god, and partook of the shark's cruel nature. He became angry with the rainbow-maiden and killed her and buried the body, but her guardian god, Pueo, the owl, scratched away the earth and brought her to life. Several times this occurred, and the owl each time restored the buried body to the wandering spirit. At last the chief buried the body deep down under the roots of a large koa-tree. The owl-god scratched and pulled, but the roots of the tree were many and strong. His claws were entangled again and again. At last he concluded that life must be extinct and so deserted the place. The spirit of the murdered girl was wandering around hoping that it could be restored to the body, and not be compelled to descend to Milu, the Under-world of the Hawaiians. Po was sometimes the Under-world, and Milu was the god ruling over Po. The Hawaiian ghosts did not go to the home of the dead as soon as they were separated from the body. Many times, as when rendered unconscious, it was believed that the spirit had left the body, but for some reason had been able to come back into it and enjoy life among friends once more. Kahala, the rainbow-maiden, was thus restored several times by the owl-god, but with this last failure it seemed to be certain that the body would grow cold and stiff before the spirit could return. The spirit hastened to and fro in great distress, trying to attract attention. If a wandering spirit could interest some one to render speedy aid, the ancient Hawaiians thought that a human being could place the spirit back in the body. Certain prayers and incantations were very effective in calling the spirit back to its earthly home. The Samoans had the same thought concerning the restoration of life to one who had become unconscious, and had a special prayer, which was known as the prayer of life, by which the spirit was persuaded to return into its old home. The Hervey Islanders also had this same conception of any unconscious condition. They thought the spirit left the body but when persuaded to do so returned and brought the body back to life. They have a story of a woman who, like the rainbow-maiden, was restored to life several times. The spirit of Kahala was almost discouraged. The shadows of real death were encompassing her, and the feeling of separation from the body was becoming more and more permanent. At last she saw a noble young chief approaching. He was Mahana, the chief of Kamoiliili. The spirit hovered over him and around him and tried to impress her anguish upon him. Mahana felt the call of distress, and attributed it to the presence of a ghost, or aumakua, a ghost-god. He was conscious of an influence leading him toward a large koa-tree. There he found the earth disturbed by the owl-god. He tore aside the roots and discovered the body bruised and disfigured and yet recognized it as the body of the rainbow-maiden whom he had loved. In the King Kalakaua version of the story Mahana is represented as taking the body, which was still warm, to his home in Kamoiliili. Mahana's elder brother was a kahuna, or witchdoctor, of great celebrity. He was called at once to pronounce the prayers and invocations necessary for influencing the spirit and the body to reunite. Long and earnestly the kahuna practised all the arts with which he was acquainted and yet completely failed. In his anxiety he called upon the spirits of two sisters who, as aumakuas, watched over the welfare of Mahana's clan. These spirit-sisters brought the spirit of the rainbow-maiden to the bruised body and induced it to enter the feet. Then, by using the forces of spirit-land, while the kahuna chanted and used his charms, they pushed the spirit of Kahala slowly up the body until "the soul was once more restored to its beautiful tenement." The spirit-sisters then aided Mahana in restoring the wounded body to its old vigor and beauty. Thus many days passed in close comradeship between Kahala and the young chief, and they learned to care greatly for one another. But while Kauhi lived it was unsafe for it to be known that Kahala was alive. Mahana determined to provoke Kauhi to personal combat; therefore he sought the places which Kauhi frequented for sport and gambling. Bitter words were spoken and fierce anger aroused until at last, by the skilful use of Kahala's story, Mahana led Kauhi to admit that he had killed the rainbow-maiden and buried her body. Mahana said that Kahala was now alive and visiting his sisters. Kauhi declared that if there was any one visiting Mahana's home it must be an impostor. In his anger against Mahana he determined a more awful death than could possibly come from any personal conflict. He was so sure that Kahala was dead that he offered to be baked alive in one of the native imus, or ovens, if she should be produced before the king and the principal chiefs of the district. Akaaka, the grandfather of Kahala, one of the mountain-gods of Manoa Valley, was to be one of the judges. This proposition suited Mahana better than a conflict, in which there was a possibility of losing his own life. Kauhi now feared that some deception might be practised. His proposition had been so eagerly accepted that he became suspicious; therefore he consulted the sorcerers of his own family. They agreed that it was possible for some powerful kahuna to present the ghost of the murdered maiden and so deceive the judges. They decided that it was necessary to be prepared to test the ghosts. If it could be shown that ghosts were present, then the aid of "spirit catchers" from the land of Milu could be invoked. Spirits would seize these venturesome ghosts and carry them away to the spirit-land, where special punishments should be meted out to them. It was supposed that "spirit catchers" were continually sent out by Milu, king of the Under-world. How could these ghosts be detected? They would certainly appear in human form and be carefully safeguarded. The chief sorcerer of Kauhi's family told Kauhi to make secretly a thorough test. This could be done by taking the large and delicate leaves of the ape-plant and spreading them over the place where Kahala Must walk and sit before the judges. A human being could not touch these leaves so carefully placed without tearing and bruising them. A ghost walking upon them could not make any impression. Untorn leaves would condemn Mahana to the ovens to be baked alive, and the spirit catchers would be called by the sorcerers to seize the escaped ghost and carry it back to spirit-land. Of course, if some other maid of the islands had pretended to be Kahala, that could be easily determined by her divine ancestor Akaaka. The trial was really a test of ghosts, for the presence of Kahala as a spirit in her former human likeness was all that Kauhi and his chief sorcerer feared. The leaves were selected with great care and secretly placed so that no one should touch them but Kahala. There was great interest in this strange contest for a home in a burning oven. The imus had been prepared: the holes had been dug, and the stones and wood necessary for the sacrifice laid close at hand. The king and judges were in their places. The multitude of retainers stood around at a respectful distance. Kauhi and his chief sorcerer were placed where they could watch closely every movement of the maiden who should appear before the judgment-seat. Kahala, the rainbow-maiden, with all the beauty of her past girlhood restored to her, drew near, attended by the two spirit-sisters who had saved and protected her. The spirits knew at once the ghost test by which Kahala was to be tried. They knew also that she had nothing to fear, but they must not be discovered. The test applied to Kahala would only make more evident the proof that she was a living human being, but that same test would prove that they were ghosts, and the spirit-catchers would be called at once and they would be caught and carried away for punishment. The spirit-sisters could not try to escape. Any such attempt would arouse suspicion and they would be surely seized. The ghost-testing was a serious ordeal for Kahala and her friends. The spirit-sisters whispered to Kahala, telling her the purpose attending the use of the ape leaves and asking her to break as many of them on either side of her as she could without attracting undue attention. Thus she could aid her own cause and also protect the sister-spirits. Slowly and with great dignity the beautiful rainbow-maiden and her friends passed through the crowds of eager attendants to their places before the king. Kahala bruised and broke as many of the leaves as she could quietly. She was recognized at once as the child of the divine rain and wind of Manoa Valley. There was no question concerning her bodily presence. The torn leaves afforded ample and indisputable testimony. Kauhi, in despair, recognized the girl whom he had several times tried to slay. In bitter disappointment at the failure of his ghost-test the chief sorcerer, as the Kalakaua version of this legend says, "declared that he saw and felt the presence of spirits in some manner connected with her." These spirits, he claimed, must be detected and punished. A second form of ghost-testing was proposed by Akaaka, the mountain-god. This was a method frequently employed throughout all the islands of the Hawaiian group. It was believed that any face reflected in a pool or calabash of water was a spirit face. Many times had ghosts been discovered in this way. The face in the water had been grasped by the watcher, crushed between his hands, and the spirit destroyed. The chief sorcerer eagerly ordered a calabash of water to be quickly brought and placed before him. In his anxiety to detect and seize the spirits who might be attending Kahala he forgot about himself and leaned over the calabash. His own spirit face was the only one reflected on the surface of the water. This spirit face was believed to be his own true spirit escaping for the moment from the body and bathing in the liquid before him. Before he could leap back and restore his spirit to his body Akaaka leaped forward, thrust his hands down into the water andseized and crushed this spirit face between his mighty hands. Thus it was destroyed before it could return to its home of flesh and blood. The chief sorcerer fell dead by the side of the calabash by means of which he had hoped to destroy the friends of the rainbow-maiden. In this trial of the ghosts the two most powerful methods of making a test as far as known among the ancient Hawaiians were put in practice. Kauhi was punished for his crimes against Kahala. He was baked alive in the imu prepared on his own land at Waikiki. His lands and retainers were given to Kahala and Mahana. The story of Kahala and her connection with the rainbows and waterfalls of Manoa Valley has been told from time to time in the homes of the nature-loving native residents of the valley. Back to Contents |

||

|

Legends of Ghosts and Gods Page 3 Back to Mo`olelo (myths/stories) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |