Legends of Ghosts and Gods

|

PART I – LEGENDS

Kauhuhu, The Shark-God Of Molokai The Shark-Man Of Waipio Valley How Milu Became The King Of Ghosts Ke-Ao-Mele-Mele, The Maid Of The Golden Cloud The Bride From The Under-World

PART II. – DESCRIPTION

Aumakuas, Or Ancestor Ghost-Gods

APPENDIX

The advancement of a people is profoundly influenced by three factors, namely: the source and quality of their food supply; their contacts and associations with other peoples; and their religious beliefs and activities. It is, perhaps, the last factor that influences people most in matters respecting their intellectual development, especially when these beliefs and activities are laid out along rational lines. As intelligence increases, knowledge is gained concerning the various phenomena of life and the relation that man bears to the forces of nature that have an influence over him. Until such a state of intelligence is attained, the developing race conceives for itself gods, ghosts, and other supernatural forms to give it the connected relations between itself and the things and phenomena of nature which cannot be understood. Through the instrumentality of these supernatural forms, the imagination of a people is developed. Songs and legends originate, blending accounts of the lives and exploits of the living and dead with those of the supernatural beings, and in time these form literature and develop arts of great value to the people. The ethnology of the peoples of the Pacific is an interesting and profitable field for study, and especially is this true of the Hawaiians, for during the period within the knowledge of man they have shown capacity for rapid intellectual development. In the dawn of their history they had no written language, but they were rich in songs and legends, not only of their own exploits, but also of their relations with the superior influences that guided their destinies. These were repeated at fireside and feast, until the imagination of the people became directive and resourceful. So there should be little wonder that they learned readily and that their transformation under organized government and institutions was rapid. The chapters that follow are replete with the richness of the imagery peculiar to the Polynesian, and no doubt none will appreciate this volume of legends more than the people of Hawaii themselves. May it serve them as a light showing the path they have trod in passing through the valley of superstition to the high lands of truth and understanding. The author is to be congratulated because of the patience and persistence with which he has worked in this little-known field of ethnology and also for the dearness and completeness of his narrative. As this part of the world comes into the full measure of its importance may this book of "Legends of Ghosts and Ghost-gods" win wide appreciation as a contribution to our knowledge of the Pacific Islands. J. W. GILMORE,

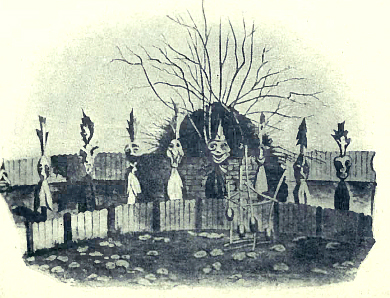

INTRODUCTIONThe legends of the Hawaiian Islands are as diverse as those of any country in the world. They are also entirely distinct in form and thought from the fairy-tales which excite the interest and wonder of the English and German children. The mythology of Hawaii follows the laws upon which all myths are constructed. The Islanders have developed some beautiful nature-myths. Certain phenomena have been observed and the imagination has fitted the story to the interesting object which has attracted attention. Now the Rainbow Maiden of Manoa, a valley lying back of Honolulu, is the story of a princess whose continual death and resurrection were invented to harmonize with the formation of a series of exquisite rainbows which are born on the mountain-sides in the upper end of the valley and die when the mist clouds reach the plain into which the valley opens. Then there were the fish of the Hawaiian Islands which vie with the butterflies of South America in their multitudinous combinations of colors. These imaginative people wondered how the fish were painted, so for a story a battle between two chiefs was either invented or taken as a basis. The chiefs fought on the mountain-sides until finally one was driven into the sea and compelled to make the deep waters his continual abiding-place. Here he found a unique and pleasant occupation in calling the various kinds of fish to his submarine home and then painting them in gay hues according to the dictates of his fancy. Thus we have a pure nature-myth developed from the love of the beautiful, one of the highest emotions dwelling in the hearts of the Hawaiians of the long ago. So, again, Maui, a wonder-working hero like the Hercules of Grecian mythology, heard the birds sing, and noted their beautiful forms as they flitted from tree to tree and mingled their bright plumage with the leaves of the fragrant blossoms. No other one of those who lived in the long ago could see what Maui saw. They heard the mysterious music, but the songsters were invisible. Many were the fancies concerning these strange creatures whom they could hear but could not see. Maui finally pitied his friends and made the birds visible. Ever since, man has been able to both hear the music and see the beauty of his forest neighbors. Such nature-myths as these are well worthy of preservation by the side of any European fairytale. In purity of thought, vividness of imagination, and delicacy of coloring the Hawaiian myths are to be given a high place in literature among the stories of nature vivified by the imagination. Another side of Hawaiian folk-lore is just as worthy of comparison. Lovers of "Jack-the-Giant-Killer," and of the many wonder-workers dwelling in the mist-lands of other nations, would enjoy reading the marvelous record of Maui, the skilful demi-god of Hawaii, who went fishing with a magic hook, and pulled up from the depths of the ocean groups of islands. This story is told in a matter-of-fact way, as if it were a fishing-excursion only a little out of the ordinary course. Maui lived in a land where volcanic fires were always burning in the mountains. Nevertheless it was a little inconvenient to walk thirty or forty miles for a live coal after the chill winds of the night had put out the fire which had been carefully protected the day before. Thus, when he saw that some intelligent birds knew the art of making a fire, he captured the leader and forced him to tell the secret of rubbing certain sticks together until fire came. Maui also made snares, captured the sun and compelled it to journey regularly and slowly across the heavens. Thus the day was regulated to meet the wants of mankind. He lifted the heavens after they had rested so long upon all the plants that their leaves were flat. There was a ledge of rock in one of the rivers, so Maui uprooted a tree and pushed it through, making an easy passage for both water and man. He invented many helpful articles for the use of mankind, but meanwhile frequently filled the days of his friends with trouble on account of the mischievous pranks which he played on them. Fairies and gnomes dwelt in the woodland, coming forth at night to build temples, or massive walls, to fashion canoes, or whisper warnings. The birds and the fishes were capable and intelligent guardians over the households which had adopted them as protecting deities. Birds of brilliant plumage and sweet song were always faithful attendants on the chiefs, and able to converse with those over whom they kept watch. Sharks and other mighty fish of the deep waters were reliable messengers for those who rendered them sacrifices, often carrying their devotees from island to island and protecting them from many dangers. Sometimes the gruesome and horrible creeps into Hawaiian folk-lore. A poison tree figures in the legends and finally becomes one of the most feared of all the gods of Hawaii. A cannibal dog, cannibal ghosts, and even a cannibal chief are prominent among the noted characters of the past. Then the power of praying a person to death with the aid of departed spirits was used, and is believed in, at the present time. Almost every valley of the island has its peculiar and interesting myth. Often there is a historical foundation which has been dealt with fancifully and enlarged into miraculous proportions. There are hidden caves, which can be entered only by diving under the great breakers or into the deep waters of inland pools, around which cluster tales of love and adventure. There are many mythological characters whose journeys extend to all the islands of the group. The Maui stories are not limited to the large island Hawaii and a part of the adjoining island which bears the name of Maui, but these stories are told in a garbled form on all the islands. So Pele, the fire-goddess, who dwelt in the hottest regions of the most active volcanoes, belongs to all, and also Kamapuaa, who is sometimes her husband, but more frequently her enemy. The conflicts between the two are often suggested by destructive lava flows checked by storms or ocean waves. It cannot be suspected that the ancient Hawaiian had the least idea of deifying fire and water--and yet the continual conflict between man and woman is like the eternal enmity between the two antagonistic elements of nature. When the borders of mist-land are crossed, a rich store of folk-lore with a historical foundation is discovered. Chiefs and gods mingle together as in the days of the Nibelungen Lied. Voyages are made to many distant islands of the Pacific Ocean, whose names are frequently mentioned in the songs and tales of the wandering heroes. A chief from Samoa establishes a royal family on the largest of the Hawaiian Islands, and a chief from the Hawaiian group becomes a ruler in Tahiti. Indeed the rovers of the Pacific have tales of seafaring which equal the accounts of the voyages of the Vikings. The legends of the Hawaiian Islands are valuable in themselves, in that they reveal an understanding of the phenomena of nature and unveil their early history with its mythological setting. They are also valuable for comparison with the legends of the other Pacific islands, and they are exceedingly interesting when contrasted with the folk-lore of other nations. The following legends treat of the worship of the lesser gods of Hawaii and of the domestic life of the Kanakas. THE AUTHOR Back to Contents PRONUNCIATION"A syllable in Hawaiian may consist of a single vowel, of a consonant united with a vowel or at most of a consonant and two vowels, never of more than one consonant. The accent of five-sixths of the words is on the penult, and a few proper names accent the first syllable. In Hawaiian every syllable ends in a vowel and no syllable can have more than three letters, generally not more than two and a large number of syllables consist of single letters-vowels. Hence the vowel sounds greatly predominate over the consonant. The language may therefore appear monotonous to one unacquainted with its force. In Hawaiian there is a great lack of generic terms, as is the case with all uncultivated languages. No people have use for generic terms until they begin to reason and the language shows that they were better warriors and poets than philosophers and statesmen. Their language, however, richly abounds in specific names and epithets. The general rule, then, is that the accent falls on the penult; but there are many exceptions and some words which look the same to the eye take on entirely different meanings by different tones, accents, or inflections. The study of these kaaos or legends would demonstrate that the Hawaiians possessed a language not only adapted to their former necessities but capable of being used in introducing the arts of civilized society and especially of pure morals, of law, and the religion of the Bible." The above quotations are from Lorrin Andrew's Dictionary of the Hawaiian Language, containing some 15,500 Hawaiian words, printed in Honolulu in 1865. Hawaiian vowels: is sounded as in father e as in they i as in marine o as in note u as in rule or as oo in moon ai when sounded as a diphthong resembles English ay au when sounded as a diphthong resembles ou as in loud The consonants are h, k, l, m, n, p, and w. No distinction is made between k and t or l and r, and w sounds like v between the penult and final syllable of a word. Back to Contents THE GHOST OF WAHAULA TEMPLEHawaiian temples were never works of art. Broken lava was always near the site. Unhewn stones were piled into massive walls and laid in terraces for altar and floors. Water-worn pebbles were carried from the beach and strewn over the floor, making a smooth place for the naked feet of the temple dwellers to pass without injury from the sharp-edged lava. Rude grass huts built on terraces were the abodes of the priests and high chiefs who visited the places of sacrifice. Elevated, flat-topped piles of stones were built at one end of the temple for the chief idols and the sacrifices placed before them. Simplicity of detail marked every step of temple erection. No hewn pillars or arched gateways of even the most primitive designs can be found in any of the temples whether of recent date or belonging to remote antiquity. There was no attempt at ornamentation even in the images of the great gods which they worshipped. Crude and hideous were the images before which they offered sacrifice and prayer. In themselves the heiaus, or temples, of the Hawaiian Islands have but little attraction. To-day they seem more like massive walled cattle-pens than places which have been used for worship. On the southeast coast of Hawaii near Kalapana is one of the largest, oldest, and best preserved heiaus. It is worthy the name of temple only as it is intimately associated with the religious customs of the Hawaiians. Its walls are several feet thick and in places ten to twelve feet high. It is divided into rooms or pens, in one of which still lies the huge sacrificial stone upon which victims--sometimes human--were slain before the bodies were placed as offerings in front of the hideous idols leaning against the stone walls. This heiau is now called Wahaula (red-mouth). In ancient times it was known as Ahaula (the red assembly), possibly denoting that at times the priests and their attendants wore red mantles in their processions or during some part of their sacred ceremonies. This temple is said to be the oldest of all the Hawaiian heiaus--except possibly the heiau at Kohala on the northern coast of the same island. These two heiaus date back in tradition to the time of Paao, the priest from Upolu, Samoa, who was said to have built them. He was the traditional father of the priestly line which ran parallel to the royal genealogy of the Kamehamehas during several centuries until the last high priest, Hewahewa, became a follower of Jesus Christ--the Saviour of the world. This was the last heiau destroyed when the ancient tabus and ceremonial rites were overthrown by the chiefs just before the coming of Christian missionaries. At that time the grass houses of the priests were burned and in these raging flames were thrown the wooden idols back of the altars and the bamboo huts of the soothsayers and the rude images on the walls, with everything combustible which belonged to the ancient order of worship. Only the walls and rough stone floors were left in the temple. In the outer temple court was the most noted sacred grave in all the islands. Earth had been carried from the mountain-sides inland. Leaves and decaying trees added to the permanency of the soil. Here in a most unlikely place it was said that all the varieties of trees then found in the islands had been gathered by the priests-- the descendants of Paao. To this day the grave stands by the temple walls, an object of superstitious awe among the natives. Many of the varieties of trees planted there have died, leaving only those which were more hardy and needed less priestly care than they received a hundred years or more ago. The temple is built near the coast on the rough, sharp, broken rocks of an ancient lava flow. In many places in and around the temple the lava was dug out, making holes three or four feet across and from one to two feet deep. These in the days of the priesthood had been filled with earth brought in baskets from the mountains. Here they raised sweet potatoes and taro and bananas. Now the rains have washed the soil away and to the unknowing there is no sign of previous agriculture. Near these depressions and along the paths leading to Wahaula other holes were sometimes cut out of the hard fine-grained lava. When heavy rains fell, little grooves carried the drops of water to these holes and they became small cisterns. Here the thirsty messengers running from one priestly clan to another, or the traveller or worshippers coming to the sacred place, could almost always find a few drops of water to quench their thirst. Usually these water-holes were covered with a large flat stone under which the water ran into the cistern. To this day these small water-places border the path across the pahoehoe[1] lava field which lies adjacent to the broken a-a lava upon which the Wahaula heiau is built. Many of them are still covered as in the days of the long ago. It is not strange that legends have developed through the mists of the centuries around this rude old temple. Wahaula was a tabu temple of the very highest rank. The native chants said,

"Enaena" means "burning with a red hot rage." The heiau was so thoroughly "tabu," or "kapu," that the smoke of its fires falling upon any of the people or even upon any one of the chiefs was sufficient cause for punishment by death, with the body as a sacrifice to the gods of the temple. These gods were of the very highest rank among the Hawaiian deities. Certain days were tabu to Lono--or Rongo, as he was known in other island groups of the Pacific Ocean. Other days belonged to Ku--who was also worshipped from New Zealand to Tahiti. At other times Kane, known as Tane by many Polynesians, was held supreme. Then again Kanaloa, or Tanaroa, sometimes worshipped in Samoa and other island groups as the greatest of all their gods--had his days especially set apart for sacrifice and chant. The Mu, or "body-catcher," of this heiau with his assistants seems to have been continually on the watch for human victims, and woe to the unfortunate man who carelessly or ignorantly walked where the winds blew the smoke from the temple fires. No one dared rescue him from the hands of the hunter of men--for then the wrath of all the gods was sure to follow him all the days of his life. The people of the districts around Wahaula always watched the course of the winds with great anxiety, carefully noting the direction taken by the smoke. This smoke was the shadow cast by the deity worshipped, and was far more sacred than the shadow of the highest chief or king in all the islands. It was always sufficient cause for death if a common man allowed his shadow to fall upon any tabu chief, i.e., a chief of especially high rank; but in this "burning tabu," if any man permitted the smoke or shadow of the god who was being worshipped in this temple to come near to him or overshadow him, it was a mark of such great disrespect that the god was supposed to be enaena, or red hot with rage. Many ages ago a young chief whom we shall know by the name Kahele determined to take an especial journey around the island visiting all the noted and sacred places and becoming acquainted with the alii, or chiefs, of the other districts. He passed from place to place, taking part with the chiefs who entertained him sometimes in the use of the papa-hee, or surf-board, riding the white-capped surf as it majestically swept shoreward--sometimes spending night after night in the innumerable gambling contests which passed under the name pili waiwai--and sometimes riding the narrow sled, or holua, with which Hawaiian chiefs raced down the steep grassed lanes. Then again, with a deep sense of the solemnity of sacred things, he visited the most noted of the heiaus and made contributions to the offerings before the gods. Thus the days passed, and the slow journey was very pleasant to Kahele. In time he came to Puna, the district in which was located the temple Wahaula. But alas! in the midst of the many stories of the past which he had heard, and the many pleasures he had enjoyed while on his journey, Kahele forgot the peculiar power of the tabu of the smoke of Wahaula. The fierce winds of the south were blowing and changing from point to point. The young man saw the sacred grove in the edge of which the temple walls could be discerned. Thin wreaths of smoke were tossed here and there from the temple fires. Kahele hastened toward the temple. The Mu was watching his coming and joyfully marking him as a victim. The altars of the gods were desolate, and if but a particle of smoke fell upon the young man no one could keep him from the hands of the executioner. The perilous moment came. The warm breath of one of the fires touched the young chief's cheek. Soon a blow from the club of the Mu laid him senseless on the rough stones of the outer court of the temple. The smoke of the wrath of the gods had fallen upon him, and it was well that he should lie as a sacrifice upon their altars. Soon the body with the life still in it was thrown across the sacrificial stone. Sharp knives made from the strong wood of the bamboo let his life-blood flow down the depressions across the face of the stone. Quickly the body was dismembered and offered as a sacrifice. For some reason the priests, after the flesh had decayed, set apart the bones for some special purpose. The legends imply that the bones were to be treated dishonorably. It may have been that the bones were folded together and known as unihipili, bones, folded and laid away for purposes of incantation. Such bundles of bones were put through a process of prayers and charms until at last it was thought a new spirit was created which dwelt in that bundle and gave the possessor a peculiar power in deeds of witchcraft. The spirit of Kahele rebelled against this disposition of all that remained of his body. He wanted to be back in his native district, that he might enjoy the pleasures of the Under-world with his own chosen companions. Restlessly the spirit haunted the dark corners of the temple, watching the priests as they handled his bones. Helplessly the ghost fumed and fretted against its condition. It did all that a disembodied spirit could do to attract the attention of the priests. At last the spirit fled by night from this place of torment to the home which he had so joyfully left a short time before. Kahele's father was the high chief of Kau. Surrounded by retainers, he passed his days in quietness and peace waiting for the return of his son. One night a strange dream came to him. He heard a voice calling from the mysterious confines of the spirit-land. As he listened, a spirit form stood by his side. The ghost was that of his son Kahele. By means of the dream the ghost revealed to the father that he had been put to death and that his bones were in great danger of dishonorable treatment. The father awoke benumbed with fear, realizing that his son was calling upon him for immediate help. At once he left his people and journeyed from place to place secretly, not knowing where or when Kahele had died, but fully sure that the spirit of his vision was that of his son. It was not difficult to trace the young man. He had left his footprints openly all along the way. There was nothing of shame or dishonor--and the father's heart filled with pride as he hastened on. From time to time, however, he heard the spirit voice calling him to save the bones of the body of his dead son. At last he felt that his journey was nearly done. He had followed the footsteps of Kahele almost entirely around the island, and had come to Puna--the last district before his own land of Kau would welcome his return. The spirit voice could be heard now in the dream which nightly came to him. Warnings and directions were frequently given. Then the chief came to the lava fields of Wahaula and lay down to rest. The ghost came to him again in a dream, telling him that great personal danger was near at hand. The chief was a very strong man, excelling in athletic and brave deeds, but in obedience to the spirit voice he rose early in the morning, secured oily nuts from a kukui-tree, beat out the oil, and anointed himself thoroughly. Walking along carelessly as if to avoid suspicion, he drew near to the lands of the temple Wahaula. Soon a man came out to meet him. This man was an Olohe, a beardless man belonging to a lawless robber clan which infested the district, possibly assisting the man-hunters of the temple in securing victims for the temple altars. This Olohe was very strong and self-confident, and thought he would have but little difficulty in destroying this stranger who journeyed alone through Puna. Almost all day the battle raged between the two men. Back and forth they forced each other over the lava beds. The chief's well-oiled body was very difficult for the Olohe to grasp. Bruised and bleeding from repeated falls on the rough lava, both of the combatants were becoming very weary. Then the chief made a new attack, forcing the Olohe into a narrow place from which there was no escape, and at last seizing him, breaking his bones, and then killing him. As the shadows of night rested over the temple and its sacred grave the chief crept closer to the dreaded tabu walls. Concealing himself he waited for the ghost to reveal to him the best plan for action. The ghost came, but was compelled to bid the father wait patiently for a fit time when the secret place in which the bones were hidden could be safely visited. For several days and nights the chief hid himself near the temple. He secretly uttered the prayers and incantations needed to secure the protection of his family gods. One night the darkness was very great, and the priests and watchmen of the temple felt sure that no one would attempt to enter the sacred precincts. Deep sleep rested upon all the temple-dwellers. Then the ghost of Kahele hastened to the place where the father was sleeping and aroused him for the dangerous task before him. As the father arose he saw this ghost outlined in the darkness, beckoning him to follow. Step by step he felt his way cautiously over the rough path and along the temple walls until he saw the ghost standing near a great rock pointing at a part of the wall. The father seized a stone which seemed to be the one most directly in the line of the ghost's pointing. To his surprise it was removed very easily from the wall. Back of it was a hollow place in which lay a bundle of folded bones. The ghost urged the chief to take these bones and depart quickly. The father obeyed, and followed the spirit guide until safely away from the temple of the burning wrath of the gods. He carried the bones to Kau and placed them in his own secret family burial cave.

The ghost of Wahaula went down to the spirit world in great joy. Death had come. The life of the young chief had been taken for temple service and yet there had at last been nothing dishonorable connected with the destruction of the body and the passing away of the spirit. Back to Contents

MALUAE AND THE UNDER-WORLDHis is a story from Manoa Valley, back of Honolulu. In the upper end of the valley, at the foot of the highest mountains on the island Oahu, lived Maluae. He was a farmer, and had chosen this land because rain fell abundantly on the mountains, and the streams brought down fine soil from the decaying forests and disintegrating rocks, fertilizing his plants. Here he cultivated bananas and taro and sweet potatoes. His bananas grew rapidly by the sides of the brooks, and yielded large bunches of fruit from their tree-like stems; his taro filled small walled-in pools, growing in the water like water-lilies, until the roots were matured, when the plants were pulled up and the roots boiled and prepared for food; his sweet potatoes--a vegetable known among the ancient New Zealanders as ku-maru, and supposed to have come from Hawaii-were planted on the drier uplands. Thus he had plenty of food continually growing, and ripening from time to time. Whenever he gathered any of his food products he brought a part to his family temple and placed it on an altar before the gods Kane and Kanaloa, then he took the rest to his home for his family to eat. He had a boy whom he dearly loved, whose name was Kaa-lii (rolling chief). This boy was a careless, rollicking child. One day the boy was tired and hungry. He passed by the temple of the gods and saw bananas, ripe and sweet, on the little platform before the gods. He took these bananas and ate them all. The gods looked down on the altar expecting to find food, but it was all gone and there was nothing for them. They were very angry, and ran out after the boy. They caught him eating the bananas, and killed him. The body they left lying under the trees, and taking out his ghost threw it into the Under-world. The father toiled hour after hour cultivating his food plants, and when wearied returned to his home. On the way he met the two gods. They told him how his boy had robbed them of their sacrifices and how they had punished him. They said, "We have sent his ghost body to the lowest regions of the Under-world." The father was very sorrowful and heavyhearted as he went on his way to his desolate home. He searched for the body of his boy, and at last found it. He saw too that the story of the gods was true, for partly eaten bananas filled the mouth, which was set in death. He wrapped the body very carefully in kapa cloth made from the bark of trees. He carried it into his rest-house and laid it on the sleeping-mat. After a time he lay down beside the body, refusing all food, and planning to die with his boy. He thought if he could escape from his own body he would be able to go down where the ghost of his boy had been sent. If he could find that ghost he hoped to take it to the other part of the Under-world, where they could be happy together. He placed no offerings on the altar of the gods. No prayers were chanted. The afternoon and evening passed slowly. The gods waited for their worshipper, but he came not. They looked down on the altar of sacrifice, but there was nothing for them. The night passed and the following day. The father lay by the side of his son, neither eating nor drinking, and longing only for death. The house was tightly closed. Then the gods talked together, and Kane said: "Maluae eats no food, he prepares no awa to drink, and there is no water by him. He is near the door of the Under-world. If he should die, we would be to blame." Kanaloa said: "He has been a good man, but now we do not hear any prayers. We are losing our worshipper. We in quick anger killed his son. Was this the right reward? He has called us morning and evening in his worship. He has provided fish and fruits and vegetables for our altars. He has always prepared away from the juice of the yellow awa root for us to drink. We have not paid him well for his care." Then they decided to go and give life to the father, and permit him to take his ghost body and go down into Po, the dark land, to bring back the ghost of the boy. So they went to Maluae and told him they were sorry for what they had done. The father was very weak from hunger, and longing for death, and could scarcely listen to them. When Kane said, "Have you love for your child?" the father whispered: "Yes. My love is without end." "Can you go down into the dark land and get that spirit and put it back in the body which lies here?" "No," the father said, "no, I can only die and go to live with him and make him happier by taking him to a better place." Then the gods said, "We will give you the power to go after your boy and we will help you to escape the dangers of the land of ghosts." Then the father, stirred by hope, rose up and took food and drink. Soon he was strong enough to go on his journey. The gods gave him a ghost body and also prepared a hollow stick like bamboo, in which they put food, battle-weapons, and a piece of burning lava for fire. Not far from Honolulu is a beautiful modern estate with fine roads, lakes, running brooks, and interesting valleys extending back into the mountain range. This is called by the very ancient name Moanalua (two lakes). Near the seacoast of this estate was one of the most noted ghost localities of the islands. The ghosts after wandering over the island Oahu would come to this place to find a way into their real home, the Under-world or Po. Here was a ghostly breadfruit-tree named Lei-walo, possibly meaning "the eight wreaths" or " the eighth wreath"--the last wreath of leaves from the land of the living which would meet the eyes of the dying. The ghosts would leap or fly or climb into the branches of this tree, trying to find a rotten branch upon which they could sit until it broke and threw them into the dark sea below. Maluae climbed up the breadfruit-tree. He found a branch where ghosts were sitting waiting for it to fall. His weight was so much greater than theirs that the branch broke at once, and down they all fell into the land of Po. He needed merely to taste the food in his hollow cane to have new life and strength. This he had done when he climbed the tree; thus he had been able to push past the fabled guardians of the pathway of the ghosts in the Upper-world. As he entered the Under-world he again tasted the food of the gods and he felt himself growing stronger and stronger. He took a magic war-club and a spear out of the cane given by the gods. Ghostly warriors tried to hinder his entrance into the different districts of the dark land. The spirits of dead chiefs challenged him when he passed their homes. Battle after battle was fought. His magic club struck the warriors down, and his spear tossed them aside. Sometimes he was warmly greeted and aided by ghosts of kindly spirit. Thus he went from place to place, searching for his boy, finding him at last, as the Hawaiians quaintly expressed it, "down in the papa-ku" (the established foundation of Po), choking and suffocating from the bananas of ghost-land which he was compelled to continually force into his mouth. The father caught the spirit of the boy and started back toward the Upper-world, but the ghosts surrounded him. They tried to catch him and take the spirit away from him. Again the father partook of the food of the gods. Once more he wielded his war-club, but the hosts of enemies were too great. Multitudes arose or, all sides, crushing him by their overwhelming numbers. At last he raised his magic hollow cane and took the last portion of food. Then he poured out the portion of burning lava which the gods had placed inside. It fell upon the dry floor of the Under-world. The flames dashed into the trees and the shrubs of ghost-land. Fire-holes opened and streams of lava burst out. Backward fled the multitudes of spirits. The father thrust the spirit of the boy quickly into the empty magic cane and rushed swiftly up to his home-land. He brought the spirit to the body lying in the rest-house and forced it to find again its living home. Afterward the father and the boy took food to the altars of the gods, and chanted the accustomed prayers heartily and loyally all the rest of their lives. Back to Contents

A GIANT'S ROCK-THROWINGA point of land on the northwestern coast of the island Oahu is called Kalae-o-Kaena which means "The Cape of Kaena." A short distance from this cape lies a large rock which bears the name Pohaku-o-Kauai, or rock of Kauai, a large island northwest of Oahu. This rock is as large as a small house. There is an interesting legend told on the island of Oahu which explains why these names have for generations been fastened to the cape and to the rock. A long time ago there lived on Kauai a man of wonderful power, Hau-pu. When he was born, the signs of a demi-god were over the house of his birth. Lightning flashed through the skies, and thunder reverberated--a rare event in the Hawaiian Islands, and supposed to be connected with the birth or death or some very unusual occurrence in the life of a chief. Mighty floods of rain fell and poured in torrents down the mountain-sides, carrying the red iron soil into the valleys in such quantities that the rapids and the waterfalls became the color of blood, and the natives called this a blood-rain. During the storm, and even after sunshine filled the valley, a beautiful rainbow rested over the house in which the young chief was born. This rainbow was thought to come from the miraculous powers of the new-born child shining out from him instead of from the sunlight around him. Many chiefs throughout the centuries of Hawaiian legends were said to have had this rainbow around them all their lives. Hau-pu while a child was very powerful, and after he grew up was widely known as a great warrior. He would attack and defeat armies of his enemies without aid from any person. His spear was like a mighty weapon, sometimes piercing a host of enemies, and sometimes putting aside all opposition when he thrust it into the ranks of his opponents. If he had thrown his spear and if fighting with his bare hands did not vanquish his foes, he would leap to the hillside, tear up a great tree, and with it sweep away all before him as if he were wielding a huge broom. He was known and feared throughout all the Hawaiian Islands. He became angry quickly and used his great powers very rashly. One night he lay sleeping in his royal rest-house on the side of a mountain which faced the neighboring island of Oahu. Between the two islands lay a broad channel about thirty miles wide. When clouds were on the face of the sea, these islands were hidden from each other; but when they lifted, the rugged valleys of the mountains on one island could be clearly seen from the other. Even by moonlight the shadowy lines would appear. This night the strong man stirred in his sleep. Indistinct noises seemed to surround his house. He turned over and dropped off into slumber again. Soon he was aroused a second time, and he was awake enough to hear shouts of men far, far away. Louder rose the noise mixed with the roar of the great surf waves, so he realized that it came from the sea, and he then forced himself to rise and stumble to the door. He looked out toward Oahu. A multitude of lights were flashing on the sea before his sleepy eyes. A low murmur of many voices came from the place where the dancing lights seemed to be. His confused thoughts made it appear to him that a great fleet of warriors was coming from Oahu to attack his people. He blindly rushed out to the edge of a high precipice which overlooked the channel. Evidently many boats and many people were out in the sea below. He laughed, and stooped down and tore a huge rock from its place. This he swung back and forth, back and forth, back and forth, until he gave it great impetus which added to his own miraculous power sent it far out over the sea. Like a great cloud it rose in the heavens and, as if blown by swift winds, sped on its way. Over on the shores of Oahu a chief whose name was Kaena had called his people out for a night's fishing. Canoes large and small came from all along the coast. Torches without number had been made and placed in the canoes. The largest fish-nets had been brought. There was no need of silence. Nets had been set in the best places. Fish of all kinds were to be aroused and frightened into the nets. Flashing lights, splashing paddles, and clamor from hundreds of voices resounded all around the nets. Gradually the canoes came nearer and nearer the centre. The shouting increased. Great joy ruled the tumult which drowned the roar of the waves. Across the channel and up the mountain-sides of Kauai swept the shouts of the fishing-party. Into the ears of drowsy Hau-pu the noise forced itself. Little dreamed the excited fishermen of the effect of this on far-away Kauai. Suddenly something like a bird as large as a mountain seemed to be above, and then with a mighty sound like the roar of winds it descended upon them. Smashed and submerged were the canoes when the huge boulder thrown by Hau-pu hurled itself upon them. The chief Kaena and his canoe were in the centre of this terrible mass of wreckage, and he and many of his people lost their lives. The waves swept sand upon the shore until in time a long point of land was formed. The remaining followers of the dead chief named this cape "Kaena." The rock thrown by Hau-pu embedded itself in the depths of the ocean, but its head rose far above the water, even when raging storms dashed turbulent waves against it. To this death-dealing rock the natives gave the name "Rock of Kauai." Thus for generations has the deed of the man of giant force been remembered on Oahu, and so have a cape and a rock received their names. Back to Contents KALO-EKE-EKE, THE TIMID TARO

A myth is a purely imaginative story. A legend is a story with some foundation in fact. A fable tacks on a moral. A tradition is a myth or legend or fact handed down from generation to generation. The old Hawaiians were frequently mythmakers. They imagined many a fairy-story for the different localities of the islands, and these are very interesting. The myth of the two taro plants belongs to South Kona, Hawaii, and affords an excellent illustration of Hawaiian imagination. The story is told in different ways, and came to the writer in the present form: A chief lived on the mountain-side above Hookena. There his people cultivated taro, made kapa cloth, and prepared the trunks of koa-trees for canoes. He had a very fine taro patch. The plants prided themselves upon their rapid and perfect growth. In one part of the taro pond, side by side, grew two taro plants--finer, stronger, and more beautiful than the others. The leaf stalks bent over in more perfect curves: the leaves developed in graceful proportions. Mutual admiration filled the hearts of the two taro plants and resulted in pledges of undying affection. One day the chief was talking to his servants about the food to be made ready for a feast. He ordered the two especially fine taro plants to be pulled up. One of the servants came to the home of the two lovers and told them that they were to be taken by the chief. Because of their great affection for each other they determined to cling to life as long as possible, and therefore moved to another part of the taro patch, leaving their neighbors to be pulled up instead of themselves. But the chief soon saw them in their new home and again ordered their destruction. Again they fled. This happened from time to time until the angry chief determined that they should be taken, no matter what part of the pond they might be in. The two taro plants thought best to flee, therefore took to themselves wings and made a short flight to a neighboring taro patch. Here again their enemy found them. A second flight was made to another part of South Kona, and then to still another, until all Kona was interested in the perpetual pursuit and the perpetual escape. At last there was no part of Kona in which they could be concealed. A friend of the angry chief would reveal their hiding-place, whileone of their own friends would give warning of the coming of their pursuer. At last they leaped into the air and flew on and on until they were utterly weary and fell into a taro patch near Waiohinu. But their chief had ordered the imu (cooking-place) to be made ready for them, and had hastened along the way on foot, trying to capture them if at any time they should try to alight. However, their wings moved more swiftly than his feet, so they had a little rest before he came near to their new home. Then again they lifted themselves into the sky. Favoring winds carried them along and they flew a great distance away from South Kona into the neighboring district of Kau. Here they found a new home under a kindly chief. Here they settled down and lived many years under the name of Kalo-eke-eke, or "The Timid Taro." A large family grew up about them and a happy old age blessed their declining days. It is possible that this beautiful little story may have grown out of the ancient Hawaiian unwritten law which sometimes permitted the subjects of a chief to move away from their home and transfer their allegiance to some neighboring ruler. Back to Contents LEGENDARY CANOE-MAKINGSome of the Hawaiian trees have beautifully grained wood, and at the present time are very valuable for furniture and interior decoration. The koa is probably the best of the trees of this class. It is known as the Hawaiian mahogany. The grain is very fine and curly and wavy, and is capable of a very high polish. The koa still grows luxuriantly on the steep sides and along the ridges of the high mountains of all the islands of the Hawaiian group. It has great powers of endurance. It is not easily worn by the pebbles and sand of the beach, nor is it readily split or broken by the tempestuous waves of the ocean, therefore from time immemorial the koa has been the tree for the canoe and surf-board of the Hawaiians. Long and large have been the canoes hewn from the massive tree trunks by the aid of the koi-pohaku, the cutting stone, or adze, of ancient Hawaii. Sometimes these canoes were given miraculous powers of motion so that they swept through the seas more rapidly than the swiftest shark. Often the god of the winds, who had special care over some one of the high chiefs, would carry him from island to island in a canoe which never rested when calms prevailed or stopped when fierce waves wrenched, but bore the chief swiftly and unfailingly to the desired haven. There is a delightful little story about a chief who visited the most northerly island, Kauai. He found the natives of that island feasting and revelling in all the abandon of savage life. Sports and games innumerable were enjoyed. Thus day and night passed until, as the morning of a new day dawned, an unwonted stir along the beach made manifest some event of very great importance. The new chief apparently cared but little for all the excitement. The king of the island had sent one of his royal ornaments to a small island some miles distant from the Kauai shores. He was blessed with a daughter so beautiful that all the available chiefs desired her for wife. The father, hoping to avoid the complications which threatened to involve his household with the households of the jealous suitors, announced that he would give his daughter to the man who secured the ornament from the far-away island. It was to be a canoe race with a wife for the prize. The young chiefs waited for the hour appointed. Their well-polished koa canoes lined the beach. The stranger chief made no preparation, Quietly he enjoyed the gibes and taunts hurled from one to another by the young chiefs. Laughingly he requested permission to join in the contest, receiving as the reward for his request a look of approbation from the handsome chiefess. The word was given. The well-manned canoes were pushed from the shore and forced out through the inrolling surf. In the rush some of the boats were interlocked with others, some filled with water, while others safely broke away from the rest and passed out of sight toward the coveted island. Still the stranger seemed to be in no haste to win the prize. The face of the chiefess grew dark with disappointment. At last the stranger launched his finely polished canoe and called one of his followers to sail with him. It seemed to be utterly impossible for him to even dream of securing the prize, but the canoe began to move as if it had the wings of a swift bird or the fins of fleetest fish. He had taken for his companion in his magic canoe one of the gods controlling the ocean winds. He was first to reach the island. Then he came swiftly back for his bride. He made his home among his new friends. The Hawaiians had many interesting ceremonies in connection with the process of securing the tree and fashioning it into a canoe. David Malo, a Hawaiian writer of about the year 1840, says, "The building of a canoe was a religious matter." When a man found a fine koa tree he went to the priest whose province was canoe-making and said, "I have found a koa-tree, a fine large tree." On receiving this information the priest went at night to sleep before his shrine. If in his sleep he had a vision of some one standing naked before him, he knew that the koa-tree was rotten, and would not go up into the woods to cut that tree. If another tree was found and he dreamed of a handsome well-dressed man or woman standing before him, when he awoke he felt sure that the tree would make a good canoe. Preparations were made accordingly to go into the mountains and hew the koa into a canoe. They took with them as offerings a pig, coconuts, red fish, and awa. Having come to the place they rested for the night, sacrificing these things to the gods. Sometimes, when a royal canoe was to be prepared, it seems as if human beings were also brought and slain at the root of the tree. There is no record of cannibalism connected with these sacrifices, and yet when the pig and fish had been offered before the tree, usually a hole was dug close to the tree and an oven prepared in which the meat and vegetables were cooked for the morning feast of the canoe-makers. The tree was carefully examined and the signs and portents noted. The song of a little bird would frequently cause an entire change in the enterprise. When the time came to cut down the tree the priest would take his stone axe and offer prayer to the male and female deities who were supposed to be the special patrons of canoe-building, showing them the axe, and saying: "Listen now to the axe. This is the axe which is to cut down the tree for the canoe." David Malo says: "When the tree began to crack, ready to fall, they lowered their voices and allowed no one to make a disturbance. When the tree had fallen, the head priest mounted the trunk and called out, 'Smite with the axe, and hollow the canoe.' This was repeated again and again as he walked along the fallen tree, marking the full length of the desired canoe." Dr. Emerson gives the following as one of the prayers sometimes used by the priest when passing along the trunk of the tree:

After the canoe had been roughly shaped, the ends pointed, the bottom rounded, and perhaps a portion of the inside of the log removed, the people fastened lines to the canoe to haul it down to the beach. When they were ready for the work the priest again prayed: "Oh, canoe gods, look you after this canoe. Guard it from stem to stern, until it is placed in the canoe-house." Then the canoe was hauled by the people in front, or held back by those who were in the rear, until it had passed all the hard and steep places along the mountain-side and been put in place for the finishing touches. When completed, pig and fish and fruits were again offered to the gods. Sometimes human beings were again a part of the sacrifice. Prayers and incantations were part of the ceremony. There was to be no disturbance or noise, or else it would be dangerous for its owner to go out in his new canoe. If all the people except the priest had been quiet, the canoe was pronounced safe. It is said that the ceremony of lashing the outrigger to the canoe was of very great solemnity, probably because the ability to pass through the high surf waves depended so much upon the outrigger as a balance which kept the canoe from being overturned. The story of Laka and the fairies is told to illustrate the difficulties surrounding canoe-making. Laka desired to make a fine canoe, and sought through the forests for the best tree available. Taking his stone axe he toiled all day until the tree was felled. Then he went home to rest. On the morrow he could not find the log. The trees of the forest had been apparently undisturbed. Again he cut a tree, and once more could not find the log. At last he cut a tree and watched in the night. Then he saw in the night shadows a host of the little people who toil with miraculous powers to support them. They raised the tree and set it in its place and restored it to its wonted appearance among its fellows. But Laka caught the king of the gnomes and from him learned how to gain the aid rather than the opposition of the little people. By their help his canoe was taken to the shore and fashioned into beautiful shape for wonderful and successful voyages. Back to Contents |

||

|

Legends of Ghosts and Gods Page 2 Back to Mo`olelo (myths/stories) |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |