History of the Hawaiian or Sandwich Islands

by James Jackson Jarves

|

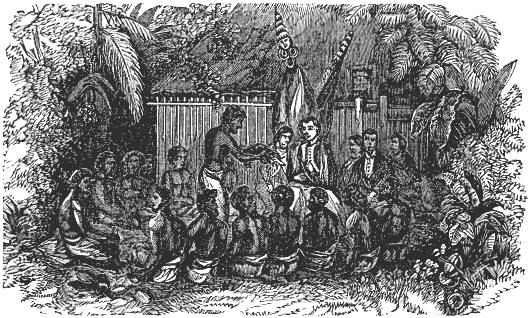

HISTORY OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS CHAPTER 5 Visits to the Hawaiian Islands previous to Cook Anson's chart Spaniards acquainted Shipwreck at Kealakeakua Bay Ships seen First appearance of Cook His reception Astonishment of islanders Effects of visit War on Maui Cook's re-appearance First notice of Kamehameha Cook's arrival at Kealakeakua Bay His deification Remarks Native hospitality Thefts Cook's desecration of the temple Growing dislike of natives Ships sail Return Succeeding events Cook's death Ledyard's account Native do Review of proceedings Recovery of bones Peace Departure of ships Touch at Oahu Arrive at Kauai Wars Attacked by natives Visit Niihau Final departure There are substantial reasons for believing that the Hawaiian Islands were visited by Europeans two centuries or more before the era of Cook. Among the natives the knowledge of such events has been perpetuated in numerous traditions, which coincide with so much collateral evidence as to place it beyond doubt. It is impossible to ascertain the precise time of these visits, though from the reigns to which they are referred, and the few particulars which have been preserved relative to them, they must have been long anterior to that of the English navigator. If their original discoverers were the Spaniards, as is highly probable, they were acquainted with their position previous to the seventeenth century. According to an old authority, Quiros sighted them in 1696, on a voyage from Manila to New Spain. In a chart of that period, taken by Admiral Anson from a Spanish galleon, a cluster of islands called La Mesa, Los Majos, La Desgraciada, is found delineated, in the same latitude as the Hawaiian Islands, and bearing the same relative situation to Roca Partida as on modern charts, though several hundred miles farther eastward. As the Spanish charts of that time were not remarkable for accuracy, the discoveries of Quiros, Mendana and others, in the Pacific, being also placed in the same relative nearness to the coast of America, this may have been an error, either of calculation, the engravers, or of design. Lying directly in the course of their rich Manila galleons, they would have afforded a secure retreat for the buccaneers and their numerous naval enemies; consequently it would have been a matter of policy to have confined the knowledge of their situation to their own commanders navigating these seas. As their number was small, rarely more than one ship annually following that track, it is no matter of surprise that they should have become forgotten, or perhaps the memory of them revived only at intervals, by their being seen at a distance. Their first visitors must have discovered that there were no mineral treasures to reward a conquest; and little else in those days sufficed to tempt the Spanish hidalgo to new scenes of adventure and hardship. The name of one, Mesa, which means table, agrees very well with the flat appearance of Mauna Loa on Hawaii, seen at a great distance. Captain King, in approaching it, called it "table-land." The fact that no other group of islands exists in their vicinity strengthens the supposition in regard to the identity of the cluster upon the Spanish chart, with the modern Hawaiian Islands. We must look for further proof from the aborigines themselves. Cook found in the possession of the natives of Kauai two pieces of iron; one a portion of a hoop, and the other appeared to be part of the blade of a broadsword. The knowledge and use of iron was generally known. These relics may have been the fruit of the voyages of the natives themselves, to some of the islands more to the westward, which had been visited by Europeans, or they may have drifted ashore attached to some portion of an wreck. But it is more probable that they were left by foreigners themselves, a supposition which coincides with traditions. The long time which had elapsed since their first arrival and the small store of property brought with them, would naturally account for so little having survived the multifarious purposes, to which, from its great utility, it was applied. The value attached to these foreign articles must have led to frequent contests for their possession, which would greatly add to their chances of being lost. Tradition states that ships were seen, many generations back, to pass the islands at a distance. They were called moku, "islands," a name which vessels of every description have since retained. We have several accounts of the arrival of different parties of foreigners. In the reign of Kahoukapu a kahuna, "priest," arrived at Kohala, the northwest point of Hawaii. He was a white man, and brought with him a large and a small idol, which by his teachings and persuasions, were enrolled in the Hawaiian calendar of gods and a temple erected for them. Paao, such was his name, soon acquired power and influence, which he exercised in the cause of humanity, by inducing the king to spare the life of one of his sons who had been ordered to execution. Kahoukapu reigned eighteen generations of kings previous to Kamehameha I. As few died natural deaths, their reigns were short, probably not averaging above ten to fifteen years each. If such were the case, it would bring the arrival of Paao to somewhere between the years 1530 and 1600, a period brilliant in the annals of Spanish maritime discovery in the Pacific. From 1568 to 1595, Mendana crossed the ocean twice, and fell in with several groups. Quiros, a few years afterward, discovered Tahiti, New Hebrides and many other islands. It is not an unreasonable conjecture to suppose that some zealous friar, at his own request, was left upon Hawaii, in the hope of converting the natives to the Roman Catholic faith, or he may have been the sole survivor of a shipwreck. The idols were possibly an image and crucifix, though no traces of the latter have been discovered. Opili, the son of Paao, succeeded him in his religious offices. During his life a party of white men are said to have landed on the southwest part of the island, and gone inland, and taken up their abode in the mountains. The natives viewed them with mysterious dread, doubtful whether they were of divine or merely human origin. Opili was sent for, and his advice asked as to the manner of opening an intercourse and propitiating them. By his directions great quantities of provisions were prepared and sent them, in solemn procession. Opili, with several others of distinction, walked at the head of the party, bearing white flags, symbolical of their peaceful intentions. The strangers seeing this, ventured from their retreat. The baked pigs and potatoes and other dainties were deposited on the ground, and the carriers retreated a short distance. When the foreigners approached, Opili spoke to them. The presents were gladly received, and a conversation the particulars of which unfortunately were not preserved, kept up for some time. It seems that Opili conversed freely with them, which was supposed by the natives to have been owing to a miraculous gift of language, but he probably had acquired from his father some knowledge of his tongue. The strangers were ever after regarded as gods, and treated with the utmost respect, though they did not remain on the island. Tradition states not how they embarked. The principal personage was called malihini; this term is still common to the Marquesan, Society and Hawaiian Islands, and is used to designate a stranger, guest or visitor. Another, and more precise tradition, relates that a few years after the departure of the former party, another arrived at Kealakeakua Bay, on the west side of Hawaii. Their boat had no masts or sails, but was painted, and an awning was spread over the stern. They were all clad in white and yellow cloth, and one wore a plumed hat. At his side hung a long knife, "pahi" which term is still applied to a sword. This party remained, and formed amicable alliances with the natives, and by their superior skill and knowledge, soon rose to be chiefs and famed warriors, and for a considerable period governed Hawaii. In the reign of Kealiiokaloa, son of Umi, thirteen generations of kings before Cook's arrival, which, according to the previous calculation, would bring it near the year 1620, a vessel, called by the natives Konaliloha, arrived at Pale Keei, on the south side of Kealakeakua Bay, Hawaii. Here, by some accident, she was drawn into the surf and totally wrecked. The captain, Kukanaloa, and a white woman, said to be his sister, were the only persons who were saved. Upon reaching the beach, either from fear of the inhabitants, to return thanks for their safety, or perhaps from sorrow, they prostrated themselves, and remained a long time in that position. Where this took place is known at the present day by the appellation of Kulou, "bowing down." The shipwrecked strangers were hospitably received, invited to the dwellings of the natives, and food placed before them. As runs the tradition, the following question was asked, "have you ever seen this kind of food?" To which they replied, "we have it growing in our country." By what means they thus freely conversed, it is not known, though the Opili before mentioned may have again acted as interpreter. Bananas, breadfruit and ohias, "wild apples," were given them, which they ate with much satisfaction. They formed connections with the native Hawaiians, and gave birth to a mixed race, from which a number of chiefs and common people are said to have descended. Kaikioewa, the late governor of Kauai, was reputed to have been one of their descendants. It would now be a matter of much interest to know the actual fate of this, the first white woman who landed on these shores; but more than the above will probably never be known. Another statement speaks of two vessels wrecked on the northeast coast of Hawaii, and that none of the crews were saved, being either lost in the surf or murdered as soon as they landed. There is a tradition extant of a ship that touched at Maui about this period, and it is possible upon further examination, the same or others were seen at the leeward islands, as one could not be visited without a knowledge being obtained of their neighbors. In clear weather, from certain points, several islands were within the range of the eye. Though these traditions are somewhat inconsistent in a few particulars, they are quite as explicit as those that relate to their national history. The last of these visits can be referred to a period nearly a century and a half prior to Cook's arrival; a time quite sufficient to have dimmed the recollection of events and thrown a mystery over the whole. Enough has been preserved to establish the fact that centuries since, vessels visited these islands, and parties of white men landed on them and left progeny, whose descendants are distinguished even to this day, by their lighter skin, and brown or red curly hair, called ehu. A party of white men called Hea, are said to have roamed wild in the mountains, occasionally making inroads upon the more fertile districts, much to the terror of the inhabitants, particularly the females. The graceful form of the helmets and the elegance of the feathered mantles, so unlike the usual rude arts of the islanders, bearing as they did a striking resemblance, in form, to those formerly worn among the Spaniards, would seem to have derived their origin from visitors of that nation. If they were not originally the result of European taste, they formed a singular deviation from the general costume of Polynesia. The skill displayed in their martial rnanoeuvres, their phalanxes of bristling spears, their well drawn up lines of battle, all savor of foreign improvement, and may be ascribed to hints received from those, who, like waifs, were cast upon their shores, and to which they were the forerunners of a civilization destined eventually to spread over the whole group. How far their influence may have extended in improving other arts, it is impossible to ascertain; but some, particularly the good taste and pretty patterns found among their cloths, the fine polish of their wooden bowls, appear to have owed their perfection to a similar cause. That a few rude sailors or adventurers should not have been able to have revolutionized their system of religion, even if inclined, is not strange; though doubtless their influence, compared with the bloody superstitions among which they were thus cast, was in some degree humanizing. In Paao, the priest, we perceive this principle forcibly illustrated in preventing the death of a doomed man. This individual having been the son of a king, may have been the reason of its being recorded in their traditions, while less conspicuous cases of merciful interference were forgotten in the long catalogue of succeeding cruelties and crimes. I have already alluded to the striking analogies between many of their religious customs and traditions and those of early Jewish rites and scriptures. It is impossible to say that even these were not derived from these strangers in their attempt to impress upon them a purer ritual and better faith. But the fact that we find in their traditions no traces of ideas of a triune deity, of an earth-born Savior and of the Virgin Mary and other prominent points more likely to have been preached to savages by Roman Catholics than an observance of the ceremonies of Judaism, leads either to the conclusion that if once heard they have since been wholly forgotten, or we must refer those customs and traditions to a period which it would be vain even to hope to penetrate with the probability of arriving at any solution of so interesting an historical inquiry. To whatever extent these islands may have been known to the Spanish navigators or stragglers across the vast Pacific, from the earlier part of the sixteenth to the middle of the seventeenth century, who from ignorance or design, left the world unacquainted with their importance, it does not detract from the credit due to the energy and ability displayed by their English successor, Captain Cook. He was probably unaware of their true position; and if to Columbus the discovery of America is to be attributed, equally to Cook is that of the Hawaiian group. Both were simply rediscoveries; the former owing rather to the comprehensive genius of a mind that dared to originate and soar beyond his age; the latter, from actively pursuing the track of discovery, and infusing into its course renewed life and vigor. In following other and important designs, he was brought in contact with this valuable group. So long a period had elapsed since the eyes of the natives had been greeted with sights foreign to their own islands, that the memory of them had become obscure, and perhaps with the generality forgotten. The appearance of Cook's ships, when he first made Niihau and Kauai, on the 19th of January, 1778, was to their unsophisticated senses, novel, fearful and interesting. Canoes filled with wondering occupants, approached, but no inducement could prevail upon them to go on board, though they were not averse to barter. Iron was the only article prized in exchange; the use of other things was unknown and even ornaments at first despised. On the following evening, the ships came to anchor in Waimea Bay, on the south side of Kauai. As the islanders were not generally apprised of their arrival until morning, their surprise was then extreme. They asked of one another, " what is this great thing with branches? "Some replied, "it is a forest which has moved into the sea." This idea filled them with consternation. Kaneonea and Keawe, the chief rulers, sent men to examine the wonderful machines, who returned and reported abundance of iron, which gave them much joy. Their description of the persons of the seamen was after this manner: "foreheads white, bright eyes, rough garments, their speech unknown, and their heads horned like the moon;" supposing their hats to be a part of their heads. Some conjectured them to be women. The report of the great quantity of iron seen on board the ships excited the cupidity of the chiefs, and one of their warriors volunteered to seize it, saying, "I will go and take it, as it is my business to plunder." He went, and in the attempt was fired upon and killed. In the account of the commencement of the intercourse between the two races, I adhere principally to the description since given by the native historians, of the sensations and singular ideas produced in the minds of their ancestors, by the novel appearance of the strangers. It is seldom, where the disparity of power and knowledge is great, that both sides are heard. In this instance, the knowledge of writing, acquired before that generation had altogether passed away, served to preserve the memory and incidents of the strange events fresh in the minds of their children, and has given to the world the opportunity to draw just inferences from mutual relations. Both dwell with emphasis upon those circumstances which to each were the most surprising; though from the greater novelty, the astonishment was far more among the natives than their visitors, and they have recorded in their simple narratives, many trifling circumstances which were not thought worthy of place in the more enlightened accounts. Cook does not mention the death of the warrior-thief, but states that on the evening before the ships anchored, he sent some boats ashore to select a watering-place. The party, upon landing, were pressed upon by the natives, who attempted to seize their arms, oars and other articles, in consequence of which, the commanding officer gave orders to fire, which was done, and one man killed. This produced no hostility from the natives, as it accorded with their own ideas of justifiable retaliation. Throughout all the intercourse, though the natives manifested the greatest respect and kindness toward their visitors, and both parties indulged in a lucrative trade, yet their propensity for thieving was continually manifested. Perfectly ready to yield their own property or persons to the gratification of the whites, it was but natural that, without any sense of shame or wrong, they should desire the same liberties. Theft or lying were to them no crimes. Success in either was a virtue, and it was not until several severe lessons in regard to the enormity of the former had been received, that their discretion got the better of temptation. During the visit, which lasted but a few days, the commander manifested a laudable humanity, in endeavoring to shield the population from the evil effects which so inevitably result from connection between foreign seamen and the native females. But his efforts were vain. If the discipline of his own crew could have been strictly enforced, the eagerness of the women was not to be repressed. The native history thus accounts for its commencement, by which it will be seen that however praiseworthy the desires of the commanders of these expeditions may have been, the licentious habits of the natives themselves were sure to counteract them. The night after the attempt of Kapupua, the warrior-thief, many guns were discharged. The noise and fire were imagined to proceed from the god Lono, or Cook, and they at first thought of fighting him. But this design was frustrated by the advice of a female chief, who counseled them "not to fight the god, but gratify him, that he might be propitious." Accordingly she sent her own daughter, with other women, on board, who returned with the seeds of that disease, which so soon and so fatally spread itself throughout the group. On February 2nd, the ships sailed from Niihau, where they had spent the greater portion of their stay, for the Northwest Coast of America. During this time they became acquainted with the existence of Oahu, having seen it at a distance, but received no information of the more windward islands. This visit was auspicious of the great revolution which the islands were destined to undergo. It had commenced on the one side with theft and prostitution, which had been repaid by death and disease. Still the superior knowledge, humanity and forbearance of the whites had been seen and acknowledged, and their first moral lessons in the distinctions of property, the foundation of all commercial prosperity, received. The wonderful news spread rapidly. It soon reached Oahu, whence one Moho, a Hawaiian, carried the particulars to Kalaniopuu, king of Hawaii. The strange spectacle of the vessels, with their sails, spars and flags, were minutely described. "The men," he said, "had loose skins (their clothes) angular heads, and they were gods indeed. Volcanoes belching fire, burned at their mouths tobacco pipes and there were doors in their sides for property, doors which went far into their bodies pockets into which they thrust their hands, and drew out knives, iron, beads, cloth, nails, and everything else." In his description, which he gave second handed, he appears to have considered the ships, equally with their crews, as animated beings, or else to have so blended the two, as to have forgotten their appropriate distinctions; an error into which savages readily fall, and which accounts for the great abundance of fables and confused description which usually pervades their stories. He also mimicked their speech, representing it as rough, harsh and boisterous. A small piece of canvas had been procured by the chief of Kauai, which he sent as a present to the king of Oahu, who gallantly gave it to his wife. She wore it in a public procession, in the most conspicuous part of her dress, where it attracted the greatest attention. During the interval between Cook's first and last visit, a war had broken out between Hawaii and Maui, in which Kalaniopuu the Terreoboo of Cook, and Teraiobu of Ledyard the king of Hawaii, contested the sovereignty of the latter island with Kahekili Titeree the reigning prince. On this occasion, Kamehameha accompanied him. This is the first notice we have of this celebrated man, then a mere youth; but at that early age he gave evidence of courage and enterprise. On the 26th of November, 1778, a battle had been fought between the contending parties, which proved favorable to Kalaniopuu. The victors on the eve of the same day returned to Wailuku, on the north side of Maui, to refresh their forces. When the morning dawned, the stranger "islands and gods," of which they had heard, appeared in view. Cook's vessel stood in near the shore, and commenced a traffic, which the natives entered into freely and without much surprise, though observing the port-holes, they remarked to each other, "those were the doors of the things of which we have heard, that make a great noise." Kalaniopuu sent Cook off a present of a few hogs, and on the 30th went himself in state to make a visit. Kamehameha accompanied him, and with a few attendants remained all night, much to the consternation of the people on shore, who, as the vessel stood to sea, thought he had been carried off, and bitterly bewailed his supposed loss. The following morning their young chief was safely landed, and Cook, ignorant of the rank of his visitor, sailed for Hawaii, which had been discovered the previous day. On the 2nd of December, he arrived off Kohala, where his ships created much astonishment among the simple islanders. " Gods, indeed," they exclaimed; "they eat the flesh of man mistaking the red pulp of water-melons for human substance and the fire burns at their mouths." However, this opinion of their divine character did not deter them from exchanging swine and fruit for pieces of iron hoop. The definition which civilized man applies to the word God, and the attributes ascribed to the Divinity, differ materially from those of the savage. With him, any object of fear, power or knowledge is a god, though it might differ not materially from his own nature. The ancients deified their illustrious dead, and as in the case of Herod, applied the title, god, to the living. In neither case can it be supposed to denote more than an acknowledged superiority, or the strongest expression of flattery. While the Hawaiians bowed in dread to powerful deities, which in their hardened understandings filled the place of the Christian's God, they worshiped a multitude of inferior origin, whom they ridiculed or reverenced, and erected or destroyed their temples, as inclination prompted. Hence their willingness at Waimea, to fight Cook or their god Lono, as they deemed him; the readiness with which they were diverted from their purpose to try more winning means to gratify him, and the alternate love, fear and hostility with which he was afterward regarded. Cook continued his course slowly around the east end of the island, occasionally trading with the natives, whose propensity to thieving was overcome only by exhibiting the dreadful effects of fire-arms. On the 17th of January, 1779, he came to anchor in Kealakeakua Bay, in the district of Kona, the reputed spot of the landing of the Spanish adventurers two centuries before. Kalaniopuu was still engaged on Maui in preserving his conquest. At the bay it was a season of taboo, and no canoes were allowed to be afloat; but when the ships were seen, the restrictions were removed, as Lono was considered a deity, and his vessels temples. The inhabitants went on board in great crowds, and among them Palea, a high chief, whose favorable influence was secured by a few acceptable presents. The seamen employed in caulking the vessels were called the clan of Mokualii, the god of canoe-makers, and those who smoked, for it was the first acquaintance they had with tobacco, were called Lono-volcano. As at Kauai, the women were the most assiduous visitors, though great numbers of both sexes flocked around Cook to pay him divine honors. Among them was a decrepid old man, once a famed warrior, but now a priest. He saluted Captain Cook with the greatest veneration, and threw over his shoulder a piece of red cloth. Stepping back, he offered a pig, and pronounced a long harangue. Religious ceremonies similar to this were frequently performed before the commander. Great multitudes flocked to the bay. Ledyard computes their number at upwards of fifteen thousand, and states that three thousand canoes were counted afloat at once. The punctilious deference paid Cook when he first landed, was both painful and ludicrous. Heralds announced his approach and opened the way for his progress. A vast throng crowded about him; others more fearful, gazed from behind stone walls, from the tops of trees, or peeped from their houses. The moment he approached they hid themselves, or covered their faces with great apparent awe, while those nearer prostrated themselves on the earth in the deepest humility. As soon as he passed, all unveiled themselves, rose and followed him. As he walked fast, those before were obliged to bow down and rise as quickly as possible, but not always being sufficiently active, were trampled upon by the advancing crowd. At length the matter was compromised, and the inconvenience of being walked over avoided by adopting a sort of quadruped gait, and ten thousand half clad men, women and children were to be seen chasing or fleeing from Cook, on all fours. On the day of his arrival, Cook was conducted to the chief heiau and presented in great form to the idols. He was taken to the most sacred part, and placed before the principal figure, immediately under an altar of wood, on which a putrid hog was deposited. This was held toward him, while the priest repeated a long and rapidly enunciated address, after which he was led to the top of a partially decayed scaffolding. Ten men, bearing a large hog, and bundles of red cloth, then entered the temple and prostrated themselves before him. The cloth was taken from them by a priest, who encircled Cook with it in numerous folds, and afterward offered the hog to him in sacrifice. Two priests, alternately and in unison, chanted praises in honor of Lono; after which they led him to the chief idol, which, following their example, he kissed. Similar ceremonies were repeated in another portion of the heiau, where Cook, with one arm supported by the high priest, and the other by Captain King, was placed between two wooden images and anointed on his face, arms and hands with the chewed kernel of a cocoanut, wrapped in a cloth. These disgusting rites were succeeded by drinking awa, prepared in the mouths of attendants, and spit out into a drinking vessel; as the last and most delicate attention, he was fed with swine-meat which had been masticated for him by a filthy old man. No one acquainted with the customs of Polynesia could for a moment have doubted that these rites were intended for adoration. Captain King, in his account of this affair, only surmises that such may have been the intention, but affects to consider it more as the evidence of great respect and friendship. The natives say that Cook performed his part in this heathen farce, without the slightest opposition. The numerous offerings, the idols and temples to which he was borne, the long prayers, recitations and chants addressed to him, must have carried conviction to his mind that it was intended for religious homage, and the whole ceremony a species of deification or consecration of himself. If this were not enough, the fearful respect shown by the common people, who, if he walked out, fled at his presence, or fell and worshiped him, was sufficient to have convinced the most skeptical mind. What opinion then can be entertained of a highly gifted man, who could thus lend himself to strengthen and perpetuate the dark superstitions of heathenism? The apology offered was the expediency of thus securing a powerful influence over the minds of the islanders, an expediency that terminated in his destruction. While the delusion of his divinity lasted, the whole island was heavily taxed to supply the wants of the ships, or contribute to the gratification of their officers and crews, and, as was customary in such gifts, no return expected. Their kindnesses, and the general jubilee which reigned, gave a most favorable impression of native character to their visitors. Had their acquaintance with the language been better, and their intercourse with the common people more extensive, it would have appeared in its true light, as the result of a thorough despotism. On the 19th, Captain Cook visited another I heiau, or more properly a residence of the priests, with the avowed expectation of receiving similar homage; nor was he disappointed. Curiosity, and a desire to depict the scene, seemed to have been his motives in this case, for he took an artist with him, who sketched the group. Ever afterward, on landing, a priest attended him and regulated the religious ceremonies which constantly took place in his honor; offerings, chants and addresses met him at every point. For a brief period he moved among them, an earthly deity; observed, feared and worshiped. The islanders rendered much assistance in fitting the ships, and preparing them for their voyages, but constantly indulged in their national vice, theft. The highest chiefs were not above it, nor of using deception in trade. On the 24th of January, Kalaniopuu arrived from Maui, on which occasion a taboo was laid upon the natives, by which they were confined to their houses. By this, the daily supply of vegetables was prevented from reaching the vessels, which annoyed their crews exceedingly, and they endeavored, by threats and promises, to induce the natives to violate the restriction. Several attempted to do so, but were restrained by a chief, who, for thus enforcing obedience among his own subjects, had a musket fired over his head from one of the ships. This intimidated him, and the people were allowed to ply their usual traffic. Kalaniopuu and his chiefs visited Captain Cook on the 26th, with great parade. They occupied three large double canoes, in the foremost of which were the king and his retinue. Feathered cloaks and gaudy helmets glanced in the bright sunlight, and with their long, shining lances, gave them a martial appearance. In the second came the high priest and his brethren, with their hideous idols; the third was filled with offerings of swine and fruits. After paddling around the ships to the solemn chanting of the priests, the whole party made for the shore, and landed at the observatory, where Captain Cook received them in a tent. The king threw his own cloak over the shoulders of Cook, put his helmet upon his head, and in his hand a curious fan. He also presented him with several other cloaks, all of great value and beauty. The other gifts were then bestowed, and the ceremony concluded by an exchange of names, the greatest pledge of friendship. The priests then approached, made their offerings, and went through the usual religious rites, interspersed with chants and responses by the chief actors.

Kamehameha was present at this interview. Captain King describes his face as the most savage he ever beheld; its natural ugliness being heightened by a "dirty brown paste or powder," plastered over his hair. The formalities of this meeting over, the king and a number of his chiefs were carried in the pinnace to the flag-ship, where they were received with all due honors. In return for the magnificent presents, Cook gave Kalaniopuu a linen shirt and his own hanger. While these visits were being exchanged, profound silence was observed throughout the bay and on the shore. Not a canoe was afloat, nor an inhabitant to be seen, except a few who lay prostrate on the ground. The taboo interdicting the inhabitants from visiting the ships was removed at the request of Captain Cook, so far as it related to the men. No relaxation could be obtained for the women, who were forbidden all communication with the whites; the result of some unusual precaution, either to prevent the increase of venereal disease, which had already worked its way to the extremities of the group, or of an unwonted jealousy. The same boundless hospitality and kindness continued. All their simple resources were brought into requisition to amuse the followers of Lono, who, in companies or singly, traversed the country in many directions, receiving services and courtesy everywhere, which to the givers were amply repaid by their gracious reception. Not withstanding this good feeling, they contrived, as heretofore, to pilfer; for which small shot were fired at the offenders, and finally one was flogged on board the Discovery. On the 2nd of February, at the desire of the commander, Captain King proposed to the priests to purchase for fuel the railing which surrounded the top of the heiau. In this, Cook manifested as little respect for the religion in the mythology of which he figured so conspicuously, as scruples in violating the divine precepts of his own. Indeed, throughout his voyages, a spirit regardless of the rights and feelings of others, when his own were interested, is manifested, especially in the last cruise, which is a blot upon his memory. It is an unpleasant task to disturb the ashes of one whom a nation reveres; but truth demands that justice should be dispensed equally to the savage, and to the civilized man. The historian cannot so far prove false to his subject, as to shipwreck fact in the current of popular opinion. When necessary, he must stem it truthfully and manfully. To the great surprise of the proposer, the wood was readily given, and nothing stipulated in return. In carrying it to the boats, all of the idols were taken with it. King, who from the first doubted the propriety of the request, fearing it might be considered an act of impiety, says he spoke to the high priest upon the subject, who simply desired that the central one might be restored. If we are to believe him, no open resentment was expressed for this deed, and not even opposition shown. This is highly improbable, when the usual respect entertained by the natives for their temples and divinities is considered; and in no case could their religious sentiments have been more shocked. If they were silent, it was owing to the greater fear and reverence with which they then regarded Cook. Ledyard, who was one of the party employed to remove the fence, gives a much more credible account, and which differs so much from the other, that it is impossible to reconcile the two. King, in his narrative of this and subsequent events, manifests a strong desire to shield the memory of his commander from all blame. Consequently, he passes lightly over, or does not allude to many circumstances which were neither creditable to his judgment nor humanity. Ledyard, in his relation, states that Cook offered two iron hatchets for the fence, which were indignantly refused, both from horror at the proposal, and the inadequate price. Upon this denial, he gave orders to his men, to break down the fence and carry it to the boats, while he cleared the way. This was done, and the images taken off and destroyed by a few sailors, in the presence of the priests and chiefs, who had not sufficient resolution to prevent this desecration of their temple, and insult to the names of their ancestors. Cook once more offered the hatchets, and with the same result. Not liking the imputation of taking the property forcibly, he told them to take them or nothing. The priest to whom he spoke, trembled with emotion, but still refused. They were then rudely thrust into the folds of his garment, whence, not deigning to take them himself, they were taken, at his order, by one of his attendants. During this scene, a concourse of natives had assembled, arid expressed their sense of the wrong in no quiet mood. Some endeavored to replace the fence and images, but they were finally got safely on board. About this juncture, the master's mate of the Resolution had been ordered to bring off the rudder of that ship, which had been sent ashore for repairs. Being too heavy for his men, he requested the assistance of the natives. Either from sport or design, they worked confusedly and embarrassed the whites. The mate angrily struck several. A chief who was present, interposed. He was haughtily told to order his men to labor properly. This he was not disposed to do, or if he had done, his people were in no humor to comply. They hooted and mocked at the whites; stones began to fly, and the exasperated crew snatched up some treenails that laid near by, and commenced plying them vigorously about the heads and shoulders of their assailants. The fray increased, and a guard of marines was ordered out to intimidate the crowd; but they were so furiously pelted with stones, that they gladly retired, leaving the ground in possession of its owners. Other causes were at work augmenting the dissatisfaction, which the near departure of the ships alone prompted them to conceal. Familiarity tends greatly to destroy influence even with the most powerful. Cook and his companions had become common objects, and the passions they constantly displayed, so like their own, lessened the awe with which they were at first regarded. The death and burial ashore of a seaman had greatly shaken their faith in their divine origin. The most cogent reason operating to create a revulsion of feeling, was the enormous taxes with which the whole island was burdened to maintain them. Their offerings to senseless gods were comparatively few, but daily and hourly were they required for Cook and his followers. They had arrived lean and hungry they were now fat and sleek qualities which seemed only to increase the voracious appetites of the seamen. The natives, really alarmed at the prospect of a famine, for their supplies were never over-abundant for themselves, by expressive signs urged them to leave. The glad tidings that the day for sailing was nigh, soon spread, and the rejoicing people, at the command of their chief, prepared a farewell present of food, cloth and other articles, which in quantity and value, far exceeded any which had heretofore been received. They were all taken on board, and nothing given in recompense. The magnitude of the gifts from the savage, and the meanness of those from the white men, must excite the surprise of any one who peruses the narrative of this voyage. As a return for the wrestling and boxing matches, the natives were entertained with a display of fire-works, which created the greatest alarm and astonishment. They very naturally considered them flying devils, or spirits, and nothing impressed them more forcibly with the great superiority of the arts and power of the white men. On the 4th of February, the ships sailed, but were becalmed in sight of land during that and the following day, which gave Kalaniopuu a fresh occasion to exercise his hospitality, by sending off a gift of fine hogs and many vegetables. His first and last intercourse being similar acts, while his friendship, during the whole visit, was of the utmost service to the exhausted crews. But the joy of the inhabitants was destined to be of short duration. In a gale that occurred shortly after, the foremast of the Resolution was sprung, which obliged the vessels to return. They anchored in their former situation on the 11th of the same month, and sent the spar and necessary materials for repairing it ashore, with a small guard of marines. Their tents were pitched in the heiau formerly occupied. The priests, though friendly, expressed no great satisfaction at this event, but renewed their good services by proclaiming the place taboo. The damaged sails, with the workmen, were accommodated in a house belonging to them. Cook's reception this time presented a striking contrast to his last. An ominous quiet everywhere prevailed. Not a native appeared to bid them welcome. A boat being sent ashore to inquire the cause, returned with the information that the king was away, and had left the bay under a strict taboo. The sudden appearance of the ships had created a suspicion of their intentions. Another visit as expensive as the former, would entirely have drained their resources. Intercourse was soon renewed, but with a faintness which bespoke its insincerity. The connections formed by many of their females with the foreigners, to whom some were attached, served, so says native authority, to exasperate the men. The former injudicious violation of the taboos, both by seamen and officers, sometimes ignorantly, and often in contempt of what appeared to them whimsical and arbitrary restrictions, had aroused the prejudices of the mass. The women in particular had been tempted, though shuddering at the expected consequences, to violate the sacred precincts of the heiau, which had been placed at the disposal of Cook for an observatory and workshop, upon the condition that no seaman should leave it after sunset, and no native be allowed to enter it by night. The immunity from supernatural punishment with which these restrictions had been broken through on both sides, at first secretly, then openly, had encouraged further disregard of their religious observances. As no attempts had been made on the part of the officers to prevent these infringements, the mutual agreement to which was considered by the chiefs in the light of a sacred compact, they felt a natural irritation. The most sacred portion of the heiau had been used as a hospital, and for a sail-loft; with the natives, highly sacrilegious acts; and they manifested their disapprobation by burning the house which stood there, as soon as the shore party evacuated it. From these and similar causes, all amicable feeling soon came to an end. Disputes arose in traffic. The bay was again laid under taboo. Affairs went on smoothly until the afternoon of the 13th, when some chiefs ordered the natives who were employed in watering the ships, to disperse; at the same time, the natives gave indications of an attack, by arming themselves with stones. Captain King approaching with a marine, they were thrown aside, and the laborers suffered to continue their work. Cook, upon being informed of these particulars, gave orders, if the natives threw stones, or behaved insolently, to fire upon them with balls. Soon after, muskets were discharged from the Discovery at a canoe, which was being paddled in great haste for the shore, closely pursued by one of the ship's boats. In the narrative, a bold theft is said to have been the occasion of this proceeding. The natives state it was caused by their expressing dissatisfaction on account of the women, and that the foreigners seized a canoe belonging to Palea, who, in endeavoring to recover it, was knocked down with a paddle by one of the white men. This occurred during the absence of Cook, as he, with King and a marine, had endeavored, by running along the beach, to cut off the flying canoe, but arrived too late to seize the occupants. They then followed the runaways for some miles into the country, but being constantly misled by the people, they gave over their futile chase. The narrative agrees with the native account in the other particulars. The officer in charge of the pursuing boat was on his return with the goods which had been restored, when, seeing the deserted canoe, he seized it. Palea, the owner, at the same instant arrived, and claimed his property, denying all knowledge of the robbery. The officer refused to give it up; and in the scuffle which ensued, the chief was knocked down by one of the crew. The natives, who had hitherto looked quietly on, now interfered with showers of stones, which drove the whites into the water, where they swam to a rock out of reach of missiles. The pinnace was seized and plundered, and would soon have been destroyed, had not Palea, who had recovered from the stunning effects of the blow, exerted his authority and drove away the crowd. He then made signs to the crew to come and take the pinnace, which they did; he restored to them all the articles which could be obtained, at the same time expressing much concern at the affray. The parties separated in all apparent friendship, but mutual suspicion prevailed. Cook prepared for decisive measures, and ordered every islander to be turned out of the ships. The guards were doubled at the heiau. At midnight a sentinel fired upon a native, who was detected skulking about the walls. Palea taking advantage of the darkness, either in revenge for his blow, or avaricious of the iron fastenings, stole one of the Discovery's cutters which was moored to a buoy. Early the ensuing morning, Sunday, the 14th, Cook determined upon a bold and hazardous step to recover the boat. It was one which he had on previous occasions successfully practiced. His intention was to secure the king or some of the royal family, and confine them on board until the cutter was restored, and as hostages for future good conduct. This could be done only by surprise or treachery. Blinded by self-confidence to the peril of the attempt, he trusted for its success to the reverence of the natives for his person. If the cutter could not be recovered by peaceable means, he gave orders to seize every canoe which should endeavor to leave the bay. Clerke, the second in command, on whom the duty devolved to lead the shore expedition, being too ill, begged Cook to take the command. To this he agreed. The account by Ledyard of the transactions that followed, of which he was an eye-witness, being near his commander when he fell, is so explicit, and agrees so well with the statements of the natives, that I give it entire:

The following, translated from Hawaiian documents, briefly recounts the particulars:

Captain King's relation differs not materially from those given. He states that Cook, after conversing with Kalaniopuu, though he was satisfied that he was innocent of the theft, still determined to persevere in his original design. Accordingly he invited him, with his two sons, to spend the day on board the Resolution, to which they readily consented; the boys had actually embarked, when their mother, with many tears, dissuaded the party from going. He also attributes Cook's endeavors to stop the firing of the men to his humanity. The day before he had given orders to the marines to fire upon the people, if they behaved even insolently; and it is more reasonable to suppose that he had become alarmed for his own safety, and wished not farther to exasperate the natives. His look inspired consternation to the last; and it was not until his back was turned that he received his death-blow. Such was the fate of this celebrated navigator, who has identified his name with the islands which he made known to the world. By his own profession he is regarded as a martyr to his adventurous courage; while his self-denial, patience, skill and enterprise in carrying out his adventurous voyages, receive merited praise from all. The melancholy circumstances attending his untimely end, created at the time so deep a sympathy in the minds of not only his own countrymen, but of all maritime nations, as to entirely exclude inquiry into its causes, and to throw a veil over faults, which otherwise would have been conspicuous, and exhibited his character in a more faithful light. While it is not my desire to detract from the fame lawfully his due, yet I cannot, with his biographers, gloss over the events which occurred at the Hawaiian Islands. Perhaps most of the errors he committed are to be attributed to his temper, which, to use the cautious words of his attached friend and companion, King, "might have been justly blamed." No one ever made the acquaintance of the aborigines of a heretofore unknown land, under more novel, yet favorable circumstances. Public feeling had been alive for many generations, with the expectation of an old and beloved king, to be restored to them, invested with the attributes of divinity. When Cook arrived, not a doubt existed that he was that god. The resources of the natives were placed at his disposal. All that kindness, devotion and superstition could effect among a barbarous people was his. No other navigator experienced a similar welcome. He had met with a hostile spirit elsewhere, but here, so warm was his welcome, and so general the joy that prevailed, that the worst features of savage nature were masked; and, in consequence, a favorable opinion formed of their domestic life and government, which later and more extended investigations have not been able to verify. Through all his intercourse, he had but one occasion of complaint, theft. Have the natives no charge to bring against him? With his influence, much might have been done toward enlightening their minds in the fundamental principles of religion; or at all events he could have done as at a later period did Vancouver a junior officer then with him whose justice and benevolence form a strong contrast to the course of Cook. By the former they were told of the existence of one God, the Creator alike of them and the whites. From the supposed character of the latter, his instructions would have carried with them the force of revelation, and their effect could not have been otherwise than beneficial. What his course was has been shown.* Pilfering and insolence were met with death, either dealt or ordered so to be, without the slightest attempt to distinguish between the guilty and innocent. A chief, in executing a law of his sovereign, was intimidated by the firing of a musket over his head; an abuse sufficient to aggravate the most forbearing race. The remonstrances of the men for the treatment of their women met with equal injustice. No adequate returns for the great quantity of food consumed were made. It was given at first as a tribute to their newly returned god, and ever after expected on the same terms. Yet all these aggravations did not arouse the spirit of the people to resistance; not even the contempt so openly cast upon their religion and temple, until the greatest of insults was shown, in attempting to imprison their king, and to carry him off from amid his own subjects, in utter violation of all justice. If this attempt had succeeded, it would not have promoted a hospitable reception for the next visitors. But even this might have been forgiven, had not a high chief, who was peaceably crossing the bay, ignorant of the cause for which the boats were stationed, been killed by the fire of one of them. At this wanton murder, the people could no longer restrain their passions, though Lono was in their eyes a god, and immortal. They slew him. His body was carried into the interior, the bones cleaned and the flesh burned, except the heart and liver which some hungry children stole in the night and ate, supposing them to belong to a dog. All will unite in deploring a result, which from far less aggravation in a civilized community, would have terminated quite as fatally; with savages, it is astonishing it did not sooner occur. As soon as the news of the attack on Cook's party reached the other side of the bay, where were the observatory and the spars and sails of the Resolution, the natives in the vicinity commenced an assault upon the small force stationed to defend them. After being repulsed, they agreed to a truce, in which all the property belonging to the ships was carried on board. "Such was the condition of the ships, and the state of discipline, that Captain King feared for the result, if a vigorous attack had been made during the night." All reverence for Lono being now terminated, the natives appeared in their true character. They endeavored to allure small parties ashore, and insulted the comrades of the slain with the most contemptuous looks and gestures; at the same time displaying their clothes and arms in insolent triumph. A breastwork was also erected on the beach, and the women sent inland. Intercourse however was re-established, with the design of obtaining the corpse of Cook and the cutter. Several natives came off from time to time to the ships, declaring their innocence, and informed the commander, Clerke, of the warlike preparations ashore. Two individuals, on the night of the 15th, brought off a portion of the flesh of Captain Cook, weighing nine or ten pounds. The remainder, they said, had been burnt, and the bones were in possession of the chiefs. The next day additional insults were received, and a man, wearing Cook's hat, had the audacity to approach the ships, and throw stones, in bravado. The crews not being in a temper for further forbearance, with the permission of their commander, fired some of the great guns at the natives on shore. The islanders had previously put themselves under cover, so that not much damage was done. A few were killed, and Kamehameha was slightly wounded by a blow received from a stone, which had been struck by one of the balls. On the 17th, the boats were sent ashore, strongly manned, to water; but the annoyance experienced from the natives was so great, that the work proceeded slowly, although under the fire of the heavy guns from the ships. In all their attacks, the islanders displayed desperate bravery. Orders were at last given to fire some houses, in doing which the whole village, with the property of the friendly priests, was consumed. The sailors, imitating the revengeful passions of their opponents, perpetrated many cruelties. A man, attended by a dozen or more boys, bearing the usual insignia of peace, approached and was fired upon. This did not stop them; and when they reached the commanding officer, the herald was found to be the priest who had performed the services at the consecration of Captain Cook, and who had always showed himself a friend. He came to expostulate on the ingratitude of the treatment he and his brethren had received. The men, who had brought off the remains of Cook, had assured them, from the captains of the ships, that their property and persons should be respected. Relying upon this pledge, they had not, with the other inhabitants, removed their effects to a place of security, and from trusting to their promises had lost their all. The narrative does not state that he had received any satisfaction from those for whom he had exerted himself so much. While the hostilities were continued between the two parties, numbers of women remained cheerfully on board the ships, exhibiting not the slightest emotion at the heads of their countrymen which were brought off, or concern for their relatives ashore. While the village was burning, they exclaimed, "a very fine sight." A fact which powerfully illustrates the deep degradation of their sex, which could thus find amusement in the sufferings of their fellows and injuries to their country. On the evening of the 18th, messengers were sent to sue for peace; they carried with them the usual presents, which were received with the assurance that it would be granted, when the remains of Cook were restored. From them it was learned that all the bodies of the marines who fell had been burnt, except the limb-bones, which were distributed among the inferior chiefs. The hair of Captain Cook was in the possession of Kamehameha. After dark, provisions were sent to the ships, with which were two large presents from the much injured but forgiving priest. As peace was now considered declared, the natives ceased all hostilities, and mingled freely with the whites, who however remained closely upon guard. All of the bones of Captain Cook that could then be recovered, were brought on board the next day, neatly wrapped in fine tapa, ornamented with black and white feathers. Presents accompanied them. On the 21st, his gun, shoes, and some other trifles, were brought by one of the high chiefs, who represented Kalaniopuu and Kamehameha, as desirous of peace. He informed the commanders that six of the chiefs, some of whom were their best friends, had been killed. A difference of opinion prevailed among the natives as to the expediency of continuing hostile measures; but peace was finally agreed upon. The remains, which had been with so much difficulty procured, were committed to the deep on the 21st, with military honors. During this scene, the bay was deserted by the natives; but the succeeding day, on the assurance that all ill-will was then buried, many visited the ships and others sent presents of eatables. In the evening the ships sailed. On the 27th, they touched at Oahu, and a party landed on the northwest side; but meeting only a few inhabitants they sailed immediately for Kauai, and came to anchor, March 1st, off Waimea, in their old station. Here their welcome was by no means cordial. The disease which they had introduced had occasioned many deaths and much suffering. The island presented the usual spectacle of savage contention and warfare. The goats which had been left by Cook as a gift, which might eventually have proved serviceable to the inhabitants, had increased to six, but had become a source of contention between Keawe and Kaneonea. Both parties maintained their claims by force, and a battle had been fought, in which Kaneonea was worsted. A misfortune among barbarians is more likely to beget enemies than friends, as the unfortunate chief soon experienced. The goats were destroyed, but not with them the disagreement, of which they had proved the innocent cause. Keawe having allied himself to another powerful chief, aspired to the sole sovereignty. Cook being dead, the ships experienced such trouble as has commonly been received from the South Sea islanders, when no superstitious restraint, or knowledge of the superior power of the white race, existed. This was greatly aggravated by the absence of the principal chiefs. The men employed in watering were annoyed by crowds of natives, who pressed rudely upon them, and finally endeavored to wrench the muskets of the soldiers from their hands. They would not suffer the watering to proceed, unless a great price was given; demanding a hatchet for every cask of water. Neither had they forgotten their old trade. While some amused themselves by tripping up the sailors, pulling them backward by their clothes, and like vexatious tricks, others stole their hats, buckets, and one seized Captain King's cutlass from his side and made his escape. Gaining courage by the impunity with which they had thus far proceeded, they made more daring demonstrations. The casks, however, were filled, placed in the pinnace, and all embarked, excepting King and two others, when a shower of stones compelled them hastily to follow. The marines in the boat then fired two muskets, which wounded one man severely. This enraged the natives, and they prepared for a fresh attack; but the authority of some chiefs who made their appearance, drove them back. No further disturbance was experienced. The chiefs of Keawe's party paid Captain Clerke a visit, and made him several curious and valuable presents, among which were fish hooks, made from the bones of Kalaniopuu's father, who had been killed in an unsuccessful attempt to subdue Oahu. A dagger made from iron taken from a timber that had recently floated ashore, was also brought. On the 8th of March, the ships stood over to Niihau, where they remained but four days. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |