History of Later

Years

of the Hawaiian Monarchy

PART 3

|

|

HISTORICAL SKETCH OF THE ATTEMPT TO OVERTHROW THE REPUBLIC BY THE ADHERENTS OF LILIUOKALANI IN JANUARY, 1895

COMPILED BY WALLACE W. FARRINGTON

CHAPTER 1

Rise And Fall Of The Rebellion

The unfriendly attitude of the American Administration toward the Republic and the withdrawal of the United States man-of-war from the Honolulu harbor early in September, gave the adherents of Liliuokalani, who sought to re-establish Monarchical rule in the Islands, renewed assurance that theirs might be a winning cause and the spirit of conspiracy became so thoroughly established that a number of private detectives were kept in the employ of the Marshal of the Islands watching those who were suspected as possible leaders in a revolutionary movement. During the closing weeks of the year 1894, the evidence obtained by the police department made the government apprehensive of trouble, though just what form it would take, and to place the leaders in the movement was beyond the power of the officials. Many supporters of the government were disposed to criticize the Marshal as being unnecessarily cautious, but as subsequent events showed, it was by the untiring vigilance of Marshal Hitchcock that the most deep seated, and if successful, the most disastrous revolution the country has ever known, was nipped in the bud, the plot laid bare and the plotters brought to justice.

With the first days of the year 1895 came daily and steadily increasing evidence of an attempt to overthrow the Republic. The keeper of the lookout station on Diamond Head reported that he had been requested not to signal the arrival of the steamer Waimanalo off the harbor. On Thursday night, Jan. 3rd, a mysterious gathering of natives was broken up at Kakaako on the water front of the city. On the following Saturday night a large number of natives were noticed coming into the city from the outlying districts, and saloons, generally crowded with natives and half-whites on Saturday evenings, were well nigh deserted.

Sunday afternoon, January 6, 1895, the Marshal received positive information of a gathering of natives and the location of a quantity of arms at the house of Henry Bertlemann, about five miles from the city on the road running around the base of Diamond Head. Deputy Marshal Arthur M. Brown was sent out to watch the place and note those going and coming. About five o'clock in the afternoon Captain Robert Parker, senior captain of the police and a squad of native police were sent out with a warrant to search the premises. Arriving near the house they found it guarded and were fired on as they approached. This was an unexpected reception and they retreated.

Charles L. Carter, Alfred Carter, James B. Castle and A. L. C. Atkinson, who were living at Waikiki, heard the firing and armed with rifles, ran quickly toward the Bertlemann place to render aid. They met Deputy Marshal Brown with Captain Parker and the police at the entrance of the lane leading from Kapiolani Park. Mr. Atkinson was sent to town with a message, and with its reinforcement the party again returned toward the Bertlemann house. They met no resistance on entering the yard and proceeded to the house where they found Bertlemann in the sitting room, quietly reading.

Deputy Marshal Brown entered the house, made known his mission, and at the request of Bertlemann read the search warrant. Meanwhile other members of the party went around the house. As Mr. Carter and Mr. Castle approached the canoe shed, which is perhaps twenty-five feet from the house toward the sea, they saw forms in the shed and Mr. Carter rushed toward the entrance followed by Mr. Castle and Alfred Carter. Firing immediately began, Charles Carter being wounded in the breast. On entering the shed he fell and at that time undoubtedly received the fatal shot in the abdomen.

The firing became general, the native police being engaged with a number of the rebels firing from a clump of trees. Those in the canoe house quickly scattered and ran up the beach, firing as they went. The two men captured by the police were taken into the house and with Bertlemann placed under guard.

Charles Carter, who was by this time suffering from most agonizing pain, was laid on a bed in the house. The two native police, Holi and Logan who had been wounded in the scrimmage were also taken into the house where the small searching party stood watch over the prisoners and awaited assistance from the town.

The news that fighting was going on at Waikiki reached town between half past seven and eight o'clock while a large proportion of the people wore at the evening services of the churches. Marshal Hitchcock realizing that he had trouble of a serious nature on his hands called out the Citizens' Guard, the military was also ordered to rendezvous and within two hours of sounding the first alarm, the government had fully one thousand men under arms guarding the streets of the city.

A Cabinet meeting was immediately called at the police station and the advisability of declaring martial law discussed. There was a decided difference of opinion which resulted in an adjournment till the morning. Meanwhile a party of regulars under Lieut. King was sent to the Bertlemann house, and with the volunteer companies at their posts of rendezvous and the Citizens' Guard patrolling the streets the government waited for developments. Little or nothing was known of the plans or extent of the uprising. It was apparent the rebels had arms and plenty of them, but as to the number gathered at Diamond Head, their leaders and organization, the prospect of armed bands of men attacking the city from other directions, or the possibility of an uprising in the town with mobs fighting in the streets, the government knew nothing. The threatened outbreak had come come and the government must be prepared to meet force with force, was the epitome of the situation Sunday night, January 6th.

The government forces consisted of two companies of regulars, five of volunteers, including a company of Sharpshooters, the Citizens' Guard, native police and mounted patrol, in all aggregating about 1200 men. All but the Citizen's Guard were armed with regulation Springfield or Winchester rifles, the members of the last organization furnishing their own arms. The Citizens' Guard having a regular company organization under Capt. F. B. McStocker, was subject to orders from the Marshal or Attorney-General as an emergency auxiliary of the police department.

The right of writ of habeas corpus is hereby suspended and Monday morning, January 7th, at 5:30 o'clock, Charles L. Martial Law is instituted and established throughout the Carter died from wounds received in the fight of the previous Island of Oahu, to continue until further notice, during which night. This was a sad and unexpected blow to the community as it had been generally reported that his injuries were not of a serious nature. The funeral occurred on the afternoon of the same day. Charles Lunt Carter, the eldest son of H. A. P. and Sybil A. Carter, was born in Honolulu, November 30, 1864. His early education was obtained in schools of his native country, after which he attended the Michigan School of Law at Ann Arbor, graduating in 1887. He returned to Honolulu and became prominent in legal and political circles, and in 1893 was a member of the Commission sent to Washington to petition the annexation of the Islands to the United States. He was prominent in framing the Constitution of the Republic, and at the election of 1894 was elected representative to the Legislature from the Fourth District of Oahu.

In the early morning of the 7th, preparations were made to attack the force of rebels. The Cabinet held an early session and the following proclamation of Martial Law was issued:

It became evident that the active force of the rebellious element was entrenched at Diamond Head, and parties were sent out to make attacks by way of Waikiki, the Moiliili road and from the sea. The government field pieces backed up by the sharp musketry proved effective in driving the rebels toward the top of Diamond Head where they were located when the night of the 7th fell.

Within the city of Honolulu business was practically suspended, nearly all the clerks and heads of the business houses being on guard in the city or in the field. No steamers or vessels were allowed to depart, and a strict guard was kept all along the water front. About noon the Marshal began to arrest the men prominent in the Royalist cause, and by nightfall about twenty had been put in prison, including Charles Clark, who was known as one of the "hangers on" of the ex-Queen since the overthrow, and who proved a valuable witness for the government.

At the time of his arrest, a large assortment of arms nine rifles and five pistols of the finest workmanship were taken from Washington Place. Mrs. Dominis had left her residence early in the morning and with Mrs. Nowlein, one of her attendants, had gone to Ewa.

During the afternoon of January 7th, several of the rebels were captured, and from them it was learned that the insurgents were under the command of Robert Wilcox and Samuel Nowlein, with Carl Widemann, W. H. C. Greig and Louis Marshall as Lieutenants. Wilcox had received military instruction in Italy during the days of King Kalakaua, and had always displayed a revolutionary turn of mind, having been the leader of the fiasco of 1887. Samuel Nowlein served in the military under the Monarchy, and after the overthrow of 1893 had lived at Washington Place as a retainer of the ex-Queen. Widemann was the son of Judge H. A. Widemann, one of the ex-Queen's Commissioners to President Cleveland. Greig and Marshall were young clerks in business houses of Honolulu. With the exception of Marshall all these men were half-caste Hawaiians, the latter being of American parentage. Their followers were made up principally of natives and half-castes who had been day laborers about the city.

Early on the morning of the 8th, it was discovered that the rebels under cover of darkness and by reason of their superior knowledge of passes in the mountains, had escaped from Diamond Head and were endeavoring to mass their forces in one of the valleys back of Honolulu Startling rumors from the Ewa district to the effect that a filibuster party was landing near Waianae led to the dispatch of a detail from the Sharpshooters under Capt. J. A. King on the steamer Claudine to cruise about the threatened district. The story proved to be a canard, and the party returned early in the evening. Another expedition by water was made under command of Hon. H. P. Baldwin on the steamer Ke Au Hou to ascertain the condition of affairs on the other Islands, it having been rumored that an uprising would take place on Maui, simultaneously with that in Honolulu. This expedition returned on the evening of the 9th, having found everything quiet on the other Islands.

The movements of the military companies were centered on an endeavor to locate the rebel forces, and prevent their escape beyond the confines of the valleys back of the city. It soon became evident that the rebel leaders had little control over their men whose principal desire was to get away from the fighting front. On the afternoon of Wednesday, a lively skirmish was precipitated by an attempt to surround some of Wilcox's men in Manoa valley. This resulted in one rebel killed, one wounded, two taken prisoners and the final escape of the principal part of the band into Pauoa valley. The advantage of the rebels lay in their familiarity with the passes in the sharp mountain ridges that separate the valleys and the ability of the native to pick his way through the lantana thickets, which to the white man are practically impenetrable. By Wednesday night it was very apparent that so far as any offensive movement on the part of the rebels was concerned, the fighting was finished. Men taken prisoners told of days and nights in the mountains without food or shelter. They had been armed with Winchester carbines and a good portion of the men had no idea how to manipulate the guns, much less do effective work with them.

From this time on the efforts of the government forces were expended in capturing the rebel leaders, Wilcox, Nowlein, Widemann, Marshall, Greig and Lot Lane. Arrests among the whites in and about the city were constantly being made by virtue of the evidence drawn from those taken prisoners in the field and arrests made in the city. It was clear to the conspirators that the government was receiving correct information, which fact caused not a little consternation in the ranks of upwards of two hundred men who were imprisoned during the first two weeks of the rebellion.

January 14th was a notable day. In the forenoon, Nowlein, Widemann, Greig and Marshall surrendered themselves to the authorities, and during the afternoon Robert Wilcox was captured in the outskirts of the city. The men were haggard and worn and appeared thankful to escape with their lives. Feeling among the government supporters was at highest tension and it was generally demanded that the leaders of the insurrection suffer the death penalty. The murder of Charles Carter and the anarchist plan of attack, which, if carried out, must have resulted in the indiscriminate death of women and children accentuated this feeling, and again, it was believed that stern measures would put an end to the series of periodical political imbroglios from which the country had suffered during the past ten years.

Although it was the general impression that ex-Queen Liliuokalani was thoroughly conversant with every preliminary move in the plot to overthrow the Republic, and was in fact a co-conspirator, the government officials, although keeping a close watch on the woman, refrained from putting her under arrest until unquestionable evidence was obtained connecting her with the affair. On the forenoon of January 16th, Deputy Marshal Brown and Senior Captain Parker of the police force served a military warrant on the ex-Queen at her Washington Place residence. She offered no protest and accompanied them to the Executive Building, where she was taken into custody by Lieut. Col. J. H. Fisher, commanding the military forces and placed under guard in one of the commodious rooms of her former palace. Mrs. Charles Wilson accompanied her as an attendant and all possible was done to insure her comfort in the new quarters. The evening of the same day, Captain Parker and Deputy Marshal Brown accompanied by Charles Clark as a guide, searched the premises and unearthed a small arsenal consisting of eleven pistols, thirteen Springfield rifles, twenty-one Winchester rifles, five swords, thirty-eight full belts of pistol cartridges, one thousand loose cartridges and twenty-one dynamite bombs. A number of the bombs were made of cocoanut shells filled with giant powder, but the greater proportion were iron shells filled with giant powder and small bird shot, with cap and fuse ready for immediate use. These, with the draft of a new Constitution and Commissions for officials of the government that was to be instituted, left no doubt as to the knowledge of the ex-Queen Liliuokalani of the plans of the revolutionists.

Trial Of The Political Prisoners

The problem of bringing the political prisoners to justice was a matter entailing quite as much careful thought a*id discretion, as unearthing the plot of the conspirators, and putting down the rebellion. The prisoners anticipated little more consideration than would be received at the hands of a drum-head court martial, but notwithstanding the government was firm in its determination to impress upon them the serious nature of the crime committed, there was no disposition to administer punishment with radical haste or without due attention to the testimony of each defendant. Under advisement of the Executive and Advisory Councils, President Dole, by the constitutional authority vested in him as Commander-in-chief of the armed forces, caused to be issued on January 16th, an order for a Military Commission "to meet at Honolulu, Island of Oahu, on the 17th day of January, A. D. 1895, at 10 A. M., and thereafter from day to day for the trial of such prisoners as may be brought before it on the charges and specifications to be presented by the Judge Advocate."

The officers of the Court were:

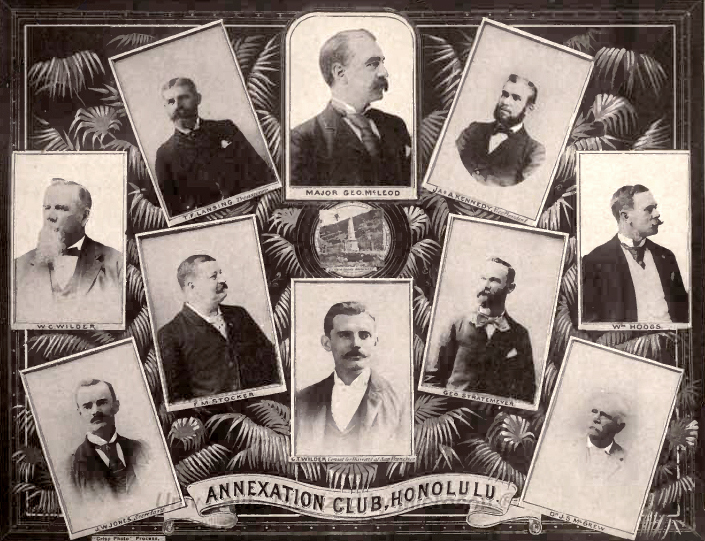

Colonel William Austin Whiting, First Regiment, N. G. H. Lieutenant-Colonol J. H. Fisher, First Regiment, N. G. H. Captain C. W. Ziegler, Company F, N. G. H. Captain J. M. Camara, Jr., Company C, N. G. H. Captain J. W. Pratt, Adjutant, N. G. H. Captain W. C. Wilder, Jr., Company D, N. G. H. First Lieutenant J. W. Jones, Company D, N. G. H. Captain William A. Kinney, Aide-de-Camp on General Staff, Judge Advocate.

Colonel Whiting and Captain Kinney were commissioned as officers of the National Guard under an act passed by the Advisory Council authorizing the Commander-in-Chief to fill vacancies by appointment during martial law. Mr. Whiting was a Judge in the Circuit Court and Mr. Kinney a member of the Honolulu bar who had assisted the Government in obtaining evidence against those implicated in the uprising. The other members of the Commission were regularly elected line officers of the military forces and had been members of the National Guard since its organization in 1893.

The trials were held in the Legislative Hall of the Executive building and were open to the general public, special accommodations also being made for the attendance of the diplomatic corps. No restrictions were placed upon the press of the country, except that no comments on the conduct of the trials or the testimony offered was allowed.

The first men brought before the Commission were Henry F. Bertelmann, W. Lane, James Lane, Carl Widemann, W. H. C. Greig, Louis Marshall, Robert W. Wilcox and Sam Nowlein, charged with "Treason, by abetting, procuring, counselling, inciting and aiding others to commit treason, and to engage in open rebellion against the Government of the Republic of Hawaii, and by attempting by force and arms to overthrow and destroy the same, and by levying war against the same." The prisoners were allowed counsel, Paul Neumann acting as the leading attorney throughout the trials. Other lawyers who appeared as counsel at different times, were Antone Rosa, S. K. Ka-ne, J. Kaulukou and Jas. A. Magoon.

One of the first moves of the counsel was to raise objection to the jurisdiction of the Commission on the following grounds: "That no military or other law exists in the Hawaiian Islands under which a Military Commission is authorized to try any person for a statutory crime. That under the proclamation of martial law the general authority of the Courts of the Republic created by the Constitution continues, and they have authority to conduct all business which comes properly before them, and have the sole authority to try persons accused of offenses such as are specified in the charges before the Commission."

Lawyer Neumann, in defending his objection, called attention to the fact that the limit of martial law is in the Commander-in-Chief. If such was the case, then the accused were not given the rights allowed under the Constitution. He claimed that the Military Commission had no right to try a crime committed against the Republic of Hawaii, which had Civil Courts in which fair trial would be given. The accused had a right to appeal to the country and its laws. There was nothing to show that the Commission had any right to act unless it showed the exigency. The rebellion was a thing of the past.

The Judge-Advocate stated that martial law is a law of necessity, in which the question of necessity rests in the discretion of the Executive and nobody can call it in question. The right had been exercised; there was nothing more to say.

Referring to the section of the order which allowed the Courts to proceed with routine business, Captain Kinney said, "Sound common sense clearly shows what the intention was, and no man need err therein, though a fool." He refused to argue whether the Executive exercised the right of law judiciously.

Answering the objection that the rebellion had been put down and no actual hostilities existed, Captain Kinney said, " God knows whether they do or not. No one knew whether they did when men hurried from their beds on the night of January 6th No man is yet assured of where we stand."

The Commission overruled the objection and the trial proceeded. Bertlemann, Wilcox and Nowlein pleaded guilty to charges and specifications. The others declined to plead on advice of counsel. The Government's case was strengthened by confessions made by Samuel Nowlein, organizer of the military rebel forces; Henry Bertleman, at whose house the first outbreak 'occurred, and Captain Davis, George Townsend and Charles Warren, who assisted in landing arms. The trial of these eight leaders in the field was completed on Saturday the 19th. With the exception of Nowlein and Bertlemann each of the prisoners went on the witness stand and made statements as to their connection with the rebellion. The counsel for the defense made a strong plea for clemency of the prisoners, most of whom were Hawaiian born. Judge-Advocate Kinney in his argument laid great stress on the fact that the time and opportunity had come to put an end to the biennial uprising to which the country had been subjected. Those representing and supporting the present and only lawful government demanded a fair, just and reasonable decision at the hands of the Commission. None of the findings of the Commission were made public till the trials were completed.

On Monday, January

21st, the Commission began the trial of Charles T. Gulick, William H.

Rickard, Thomas B. Walker and William T. Seward. These men were among

the prime movers of the revolt, although they took no part in the open

hostilities. Gulick and Seward were of American parentage, the latter

having served in the Union forces during the War of the Rebellion.

Gulick was a descendant of one of the prominent missionary families; was

a member of the Honolulu liar and took an active part in politics under

the Monarchy, serving at one time as Minister of the Interior. Rickard

and Walker

were of English parentage, the former being at one time numbered among

the well-to-do sugar planters of the country. Of late years he had lost

heavily and was practically bankrupt. Walker was a contractor and

builder, who, after the down-fall of the Monarchy, gave quite as much

attention to plotting against the Government as to his business affairs.

These four organizers of the rebellion were called to answer to the charge of treason. Gulick, Seward and Rickard plead not guilty to each charge and specification. Walker pleaded guilty to the specifications charging him with aiding and abetting rebellion and procuring munitions for the insurgents.

The trial of these four men lasted four days, during which time the witnesses for the Government laid bare the plot of the rebellion, over which these men had practically acted as supervisors.

Among the witnesses who gave the most damaging evidence were Nowlein and Bertlemann, Captain Davies, captain of the Steamer Waimanalo which was used in landing the arms; John Cummins, with whom "Major" Seward had lived during the greater part of his residence in the islands, and William F. Kaae, who had acted as private secretary to Liliuokalani during her residence at Washington place.

The evidence presented showed that Seward had made a trip to San Francisco in December of 1894, procured the arms and ammunition and arranged for shipment to Honolulu. Rickard had assumed the task of looking after the arms on their arrival. Gulick acted as legal adviser, having assisted in drafting the Constitution and Cabinet Commission for the new Government.

Walker, besides being an all round instigator, had provided for the manufacture of dynamite bombs which were to be used in the street fighting. To him had been assigned the task of leading the forces that were to attack the police station. Statements to this effect were made by Walker himself, who went on the stand as a witness in order to protect members of his family from being brought before the commission as witnesses.

On the last day of the trial Gulick made a written statement in which he denied having taken any part in or having any knowledge of the plottings against the Republic. It was proved conclusively however, that he had not only drafted the constitution, and forms for cabinet commissions and martial law orders, but meetings of the leaders had been held at his house and he had been in close touch with nearly every move of the royalists in their plans to overthrow the Republic. The evidence submitted by the prosecution was so complete, that, beyond the statement of Gulick the defense had very little to offer. As in the previous cases, the plea of the defense was for clemency. The Judge-Advocate in his closing arguments on the case, drew attention to the manner in which these men of intelligence had pushed the ignorant native into the brunt of the fight, having been careful to screen their own connection with the affair in case of the failure of the natives, but ready at the first evidence of success to come to the front and claim the glory. As for the sympathy of the accused for the natives, the Judge Advocate held that if their sympathy had led them to put fire brands in the hands of the natives it should have led them to go to the field and exercise a controlling hand. "Carter lost his life through the lack of control of the natives; certainly these leaders should have thought of the women or children in the town who would be exposed to the same danger. There was nothing manly, nothing patriotic, except possibly among the natives who went blindly to the front. The criminal act of the accused was worse than that of pirates, as they were not on the pirate deck."

On the afternoon of the' 23d of January, the first lot of natives, twelve in number, captured in the field was brought before the court on the charge of treason. The principal defense of these men as well as the majority of the rank and file of the insurgents who were brought before the court later, was that they had been forced into the fight by the foreign and half white leaders. While it is true that they were willing participants and were possibly inspired by a feeling of loyalty to the ex-Queen, had they been less under the influence of liquor, better aware of the enormity of the crime committed and the punishment to which they were liable on account of their action, it is highly probable that they would have withheld from joining the insurgent forces. The trials of the natives were slow and tedious, nearly every prisoner being enthused with a desire to question witnesses and make lengthy statements of their connection with the uprising. A second lot of thirteen natives was brought into court on the evening of Thursday the 24th, their trial continuing through the week.

The first man to be placed on trial for Misprison of Treason was John F. Bowler, a contractor and builder of Honolulu, who has always been quite prominent in politics. Counsel Neumann at the opening of this case made a strong fight against the jurisdiction of the Court, additional objections to those presented at previous trials being offered as follows:

Judge-Advocate Kinney marked the usage of martial law as different times as follows:

This trial and those for Misprison of Treason that were to follow came more correctly under the second definition.

Mr. Kinney closed by stating that it was due only to a rule of law that Bowler was not charged with treason. The Commission overruled the objections to its jurisdiction in this as in the preceding cases.

The evidence brought out in the two days' trial showed that Bowler had been aware of the plot of the insurgents, and to him had been delegated the capture of the telephone offices. The non-arrival in the city of Nowlein's forces was apparently all that prevented his taking an active part in the fighting. Bowler, however, made a statement asserting his innocence and ignorance of all plans and intentions of the insurgents.

On the afternoon of January 29, the trial of Volney V. Ashford for Misprison of Treason was opened. Outside the trial of the ex-Queen this was one of the hardest fought legal battles of the trials. The defense endeavored to break down the evidence of Samuel Nowlein who, it was understood, was to be one of the principal witnesses against Liliuokalani. All attempts in this direction were futile, however, it being shown that Ashford had acted as one of Nowlein's advisors and was conversant of the proposed outbreak. V. V. Ashford had always been active in politics, and with his brother C. W. Ashford, was always known as a rebellious spirit. He had been prominent in military circles during the reign of the Monarchy, and at one time was forced to leave the country for his participation in political plottings. After the overthrow he returned and immediately became affiliated with the royalist cause.

The most prominent persons brought before the Court from this on were ex-Queen Liliuokalani and Jonah Kalanianaole commonly known as "Prince Cupid." Their trial will be dealt with more fully in succeeding chapters. Outside these the time of the Commission was taken up principally with the trial of natives who had been connected with the affair, either as active participants in the field or guards and messengers during and previous to the outbreak.

The trial of the last case brought before the Commission ended March 1. The Commission did not adjourn sine die, however, until March 18, when all the men against whom the government held serious charges had left the country, and many who had been imprisoned during the outbreak were released.

During its session of thirty-six days, 191 prisoners were brought before the Commission. Of the 176 prisoners charged with treason five were acquitted, and in the cases of sixty-four, notably the natives on guard at Washington Place and witnesses who turned States evidence, sentence was suspended. Only two of the fifteen charged with Misprison of Treason were acquitted.

The first of the sentences were made public on February 12, when a number of natives found guilty of treason were sentenced to five years imprisonment at hard labor. A few days latter followed the sentences of Volney V. Ashford and John F. Bowler, convicted of Misprison of Treason, Ashford being sentenced to one year's imprisonment with $1,000 fine, and Bowler to five years' imprisonment and $5,000 fine. On Saturday, February 23, the sentences of the leaders were published as follows: Charles T. Gulick, W. H. Seward, Robert Wilcox, Samuel Nowlein and Henry Bertlemann, each thirty-five years' imprisonment at hard labor, with a fine of $10,000. The Military Commission had sentenced these men to suffer the death penalty, which sentence was commuted by the President as above. Sentences were suspended in the cases of Nowlein and Bertlemann, they having given important evidence. The other leaders sentenced were: T. B. Walker, thirty years and $5,000 fine; Carl Widemann, thirty years and $10,000 fine; W. H. C. Greig, twenty years and $10,000 fine; Louis Marshall, twenty years and $10,000 fine. The ex-Queen was sentenced to five years' imprisonment with $5,000 fine and Jonah Kalanianaole, commonly known as "Prince Cupid" to one year with $1,000 fine. J. A. Cummins received the same sentence as ex-Queen Liliuokalani but was released on payment of fine. The sentences of the others who were mostly natives and half castes, ranged all the way from five months to five years imprisonment, the fine, as a rule, being stricken out by the President.

Abdication And Trial Of Liliuokalani

When it became apparent that all hopes of the restoration of ex-Queen Liliuokalani had been irretrievably blighted, it became general! y rumored that the ex-Regent was prepared to make a formal abdication of her claims as the only lawful ruler of the people of Hawaii a claim to which she had adhered most tenaciously from the day of the overthrow. During her detention in the Executive Building she was in constant touch with her friends and advisers, through her agent Charles B. Wilson, who was allowed free access to her apartments by the military authorities.

On the afternoon of January 24th, the members of the Cabinet were informed that the ex-Queen had an official document which it was desired should be presented to the Executive.

They signified their willingness to listen to any communication which the now military prisoner might submit. During the latter part of the day a copy of the following correspondence was put in the hands of Attorney-General Smith. The letter was drawn by Judge A. S. Hartwell who had been consulted by Messrs. Wilson, Parker and Neumann regarding the matter, and acted as advising counsel for them. Judge Hartwell also attended the execution of the document:

On the 24th day of January, A. D. 1895, the foregoing was in our presence read over and considered carefully and deliberately by Liliuokalani Dominis, and she, the said Liliuokalani Dominis, thereupon in our presence declared that the same was a correct, exact and full statement of her wishes and acts in the premises, which statement she declared to us that she desired to sign and acknowledge in our presence as her own free act and deed, and she thereupon signed the same in our presence, and declared the same to be her free act and deed, in witness whereof we have at the request of the said Liliuokalani Dominis, and in her presence, hereunto subscribed our names is attesting witnesses, at the Executive building, in Honolulu on the Island of Oahu, this '24th day of January, A. D. 1893.

The effect of this letter of abdication was not as sensational as might be anticipated at first thought. In fact the move came about two years too late to attract extraordinary attention. In the eyes of the Government, this lady was in much the same position as a private citizen who had communicated to them concerning a change of opinion in politics. With the people, her undoubted knowledge of the plot of the proposed revolution and her "abdication" being forthcoming only when she found herself hemmed in from every side, gave her scant sympathy, consequently this belated action did not inspire the confidence in the honest intention of the move which would have resulted, had it been made at an earlier day.

The Executive submitted the letter to the Advisory Councils and later made the following reply:

That there was a latent hope that the letter of abdication would influence the government to act with leniency toward the political offenders, and the ex-Queen in particular seems highly probable. Liliuokalani had, however, been given the opportunity to retire to private life and live quietly and comfortably among her people. This opportunity had been set aside, and not until, balked on every hand in her attempts to regain her throne, did she come to realize how sweet was the freedom which she had forfeited.

Whatever hope may have existed in her mind was ill-founded, however. On Tuesday, February 5th. Liliuokalani Dominis was brought before the Military Commission charged with Misprison of Treason. The trial which occupied the greater part of four days was marked by sharp legal sparring and a flood of objections from the attorney for the defense. Among the principal witnesses against the ex-Queen were Samuel Nowlein and Charles Clark, both of whom had been "hangers on" about Washington Place since 1893, also William Kaae, who had acted as private secretary to Liliuokalani. Nowlein testified to having had charge of the arms and dynamite bombs and making arrangements to station guards about the place on the night of the outbreak. Clark had been in charge of the place during Nowlein's absence and informed Liliuokalani of the progress of the movements in the city, Kaae, the private secretary, testified to having drawn up the Commissions for the Cabinet officers of the new government, as follows:

R. W. WILCOX, Minister Foreign Affairs SAM NOWLEIN, Minister of Interior CHARLES T. GULICK, Minister of Finance C. W. ASHFORD, Attorney-General. ANTONE ROSA and V. V. ASHFORD, Associate Justices

A. S. CLEGHORN, Oahu

D.

KAWANANAKOA, Maui

That these Commissions were signed by the ex-Queen was further proven by the entry in her private diary December 28th: "Signed eleven Commissions today." Kaae had written out the forms for the Commissions, proclamations and the new Constitution, under the direction of C. T. Gulick and the ex-Queen. On Thursday, the third day of the trial, the defense submitted the following statement notwithstanding Liliuokalani had gone on the stand and made denial of any knowledge whatsoever of an attempt to restore her to the throne.

The statement was inspired by her legal adviser and was undoubtedly prepared with a view to strengthening the ex-Queen's case, not so much with the Military Commission as with the people abroad. Among her own people this statement tended to wipe out what conciliatory feeling her formal abdication may have engendered. The statement is given in full:

At the opening of the trial on Friday morning, Counsel Newmann was informed by the Commission that the following portions of his client's statement must be stricken out:

Objection was made, and overruled, to any section being stricken out without rejecting the whole statement. The arguments of the counsel for defense and the Judge-Advocate occupied the greater part of the closing day of the trial. The argument of Captain Kinney was one of the master efforts of the trial, in which the fallacies of the ex-Queen's statement were pointed out and the evidence of a desire to create sympathy, on account of alleged injuries, not only among her own people but among the citizens of foreign countries. The trial closed on the afternoon of February 7th, and the ex-Queen was returned to her apartments in the Executive building where she remained under military guard until allowed to return to her Washington Place resident on parole pardon.

Landing Arms And General Scheme Of Rebel Plot

On December 3d, 1894, Major Win. H. Seward returned from San Francisco where he had arranged for the purchase of the arms for the revolutionists and their shipment to the Islands on the schooner H. C. Wahlberg Capt. Mathew Martin commanding.

Where the funds for the purchase of the arms came from was not brought out during the trials. It is highly probable that the money was obtained by an assessment on the members of the royalist party who were either directly or indirectly interested in the success of the revolt.

Immediately after the arrival of Seward arrangements were made to receive and conceal the arms until they could be distributed among the natives. The men picked to take charge of the natives employed in this work were George Townsend and Charlie Warren a native. These men were stationed on the windward side of the island near Makapuu point. The schooner was sighted on December 19th, and after landing the revolvers and a portion of the ammunition on Rabbit island, again put to sea, where the remainder of the munitions of war were to be transferred to the steamer Waimanalo, Capt. Davis commanding, and brought into the harbor of Honolulu. The revolvers were hurried in the sands on Rabbit island and later brought to Honolulu by natives and distributed among those who were to take part in the uprising.

Captain Davis was engaged by W. H. Rickard and was promised a reward of $10,000, if the arms were successfully landed. The transfer of rifles and ammunition from the schooner to the Waimanalo was made on New Years day some twenty miles off Rabbit island. After going to the island to give notice that the arms had been secured, the steamer put to sea, and arrived off Diamond Head on the evening of the second of January. W. H. Rickard went on board, and the steamer again put to sea, it being the intention to land the arms at points along the water front of Honolulu and begin the fight on the night of January 3d. Arriving again off Diamond Head, the evening of the third, word was sent to the steamer that the men gathered at Kakaako to receive the arms had been discovered and the steamer cargo must be landed near Diamond Head. This was accordingly done, and the arms buried in the sand on the beach beyond Diamond Head.

The original plan of attack was for the arms to be landed at Kakaako, and at the fish market both places being on the city water front. The fighting was to begin immediately. White men in the city were to lead the natives, capture the station house, electric light station and telephone offices, establish posts at the junction of the streets and prevent the Citizens Guard and members of the volunteer companies from reaching their places of rendezvous. The landing on the water front having been prevented, the time for the attack was set for 2 o'clock Monday morning, January 7th.

Nowlein was to march upon the city from Waikiki; simultaneously with his movement, bands of natives led by whites were to come in from other points in the outskirts, and these parties were to be joined by natives and white royalists living in the city, and combine in a general assault upon the Government building. The surprise of Sunday night had of course disconcerted the leaders. The white royalists who were to have joined in the fight kept as quiet as possible, and made every attempt to clear their skirts of any semblance of having been associated with the affair in any way. The freedom with which liquor was dealt out to the natives, the lack of anything approaching organization in their ranks, the proposed use of dynamite bombs, and the ignorance of the natives of the use of fire arms all went to prove that, had the rebels reached the city before the government forces were able to rendezvous the morning of January 7th, 1895, would have been characterized indiscriminate slaughter in the streets of Honolulu.

Forcible And Voluntary Deportation Of Exiles

In the forcible deportation of J. Cranstoun, A. E. Meuller and J. B. Johnstone on Saturday, February 2nd, the Government made an arbitrary move which met with considerable adverse criticism, not because it was believed that the character of the men did not justify the act, but rather on account of the danger of serious diplomatic complications arising from the expulsion from the country without trial. The three men had been arrested during the early days of the outbreak for being parties to the plan to destroy public buildings with dynamite.

Johnstone had been in the employ of the Government as a detective, at the same time being hand in glove with those interested in upsetting the Republic. None of the men held any considerable amount of a property and might well be classed in the floating population of the country. On Friday these prisoners were removed from the prison to the station house, and about noon Saturday they were put on board the steamer Warrimoo of the Canadian Australian line. All three protested against their treatment and asked to see their national representatives.

Johnstone was of English birth, Mueller, German, and Craustoun claimed to be an American citizen by naturalization. The American Minister strove to impress upon the Government officials that they were making a great mistake by their arbitrary action but under advice of their foreign representatives, the German and Englishmen were inclined to accept the inevitable. The officers of the Government remained firm and having put the men on the steamer kept them there guarded by police until the vessel was well outside the harbor. On arrival in British Columbia, the exiles brought suit for damages against the steamship line for conveying them out of the country.

The cases of Cranstoun and Mueller are now going through the usual processes of law in the court of Victoria, B. C. Johnstone's claim has been withdrawn to await the verdict of the court in the cases of his brother exiles. Claims for damages were also filed with the home Governments, but none of the latter claims have been pressed up to the present time.

The position of the Hawaiian Government in the deportation of Cranstoun, Mueller and Johnstone is defined as follows in a memorandum of the law, given by General A. S. Hartwell to William A. Kinney who was retained as counsel by the Government:

In re Cranstoun, Muller and Johnstone, exiled from the Hawaiian Islands by order of President Dole, acting as Commander-in-chief of the national forces of Hawaii, during the prevalence of martial law upon the Island of Oahu of the Republic of Hawaii upon suspicion based upon facts known to the Hawaiian Government, that they were persons dangerous to the community, and implicated in the rebellion against the Government.

When the Military Commission had completed the trial of the more prominent participants in the rebellion, the desire of many citizens of the Republic to have severe punishment meted out to each and every prisoner began to cool. Those who were calling for the lives of the rebels at the outset were quite satisfied with deportation, light imprisonment or unrestricted release of those remaining. Rather than continue the trials until all those in prison had been dealt with, the Government gave many of the prisoners the option of leaving the country or going before the Commission. Most of those remaining were white residents to whom the prison life was, naturally enough, decidedly distasteful. They were totally in the dark as to the evidence which the Government could bring in at the trial, and rather than run the chances of continued imprisonment a good proportion were glad to escape by leaving the country. Each one accepting this option signed a statement similar to the following, which act, British Commissioner Hawes stated to the English subjects in the presence of the Marshal, "was a practical admission of guilt:"

"Whereas, I, __, am now held in confinement for complicity in the recent insurrection against the Hawaiian Government, and have expressed a desire to leave the country not to return, provided said Government shall in its clemency consent to such expatriation, now, therefore I, the said in consideration of the Hawaiian Government, immediately upon being released, it being understood and agreed by me that said charge is no wise withdrawn nor in any sense discontinued, do hereby agree that when allowed to leave the custody of the Marshal, I shall and will leave the Hawaiian Islands by the leaving Honolulu for February, 1895, and will not return during my life time without the written consent of the Minister of Foreign Affairs or other officer having charge of said department, approved by the Marshal."

The men who took this option were as follows: L. J. Levey, Fred. Harrison, George Ritman, John C. White, P. M. Rooney, Fred. H. Redward, Frank Honeck, Charles Creigliton, Arthur White, Arthur McDowall, A. Carriane, Fred. W. Wundenburg, Michael Cole Bailey, C. W. Ashford, C. Klemme, Harry von Werthern, John Kadin, James Brown, A. P. Peterson, P. G. Camarinos and Nichols Peterson. These men were released about a week before their departure so as to give them an opportunity to put their business affairs in order. The first lot of eleven went to San Francisco on the steamer Australia, February 23, and the others followed during the next month, with the exception of one or two whose homes were in Australia.

Later in the year V. V. Ashford, Louis Marshal and W. H. C. Greig who had been sentenced by the military court were released from prison on condition that they leave the country. With the exception of these three together with C. W. Ashford, Cranstoun, Mueller and Johnstone, all those deported were granted leave to return to the country before the end of the year.

Pardon Of Prisoners

It was hardly two months after the Military Commission held its final session when a movement was set on foot to influence the President and his advisers to exercise their prerogative and grant pardons to the political prisoners. The plea was first made by former royalist leaders and, in consequence of the apparent disposition of former enemies of the Government to accept the political situation, received not a little support from many who had stood by the Republic from its inception. It was also argued that such a course would conciliate the native population, and create a more united people.

The quiet condition of the community lent force to the plea for clemency and on the Fourth of July, 1895, almost six months after the fight in which Charles Carter was killed, forty-five of the "rank and file" of the natives incarcerated in consequence of their connection with the rebellion, were granted conditional pardons. Each and every pardon contained the following provisions: "Such sentence is suspended, and the said may go at large, subject to remand upon the order of the President."

On the same day the sentences of the leaders were commuted as follows: W. H. C. Greig, from twenty to fifteen years; T. B. Walker, thirty to fifteen years; Carl Widemann, thirty to fifteen years; Louis Marshall, twenty to fifteen years; W. H. Seward, thirty to twenty years; W. H. Rickard, thirty to twenty years; R. W. Wilcox, thirty to twenty years; and C. T. Gulick, thirty to twenty years.

In granting these pardons members of the Executive endeavored to impress upon those who had been released that upon their good behavior after obtaining their liberty depended the attitude of the Government toward the leaders of the revolt, who remained in prison.

It was not many weeks after this first act of clemency that the advocates of general pardon began to make themselves heard. The effect abroad, the strength of the Republic, its ability to maintain itself against all foes, and the conciliatory effect of such a move were the leading arguments presented. Those who opposed the general pardon held that such a move would be a practical admission that the insurrection itself, the "war" for its suppression, the lengthy continuance of martial law, the extended sessions of the military court with its extreme sentences were all in the nature of a farce and would place the officers of the Government as the leading lights in an opera bouffe.

In the face of arguments pro and con the Government held to its original policy of granting conditional pardons according as the peaceful condition of the country gave evidence that political leaders had deserted the policy of attempting to gain their ends by force of arms. Accordingly on the 5th of September the President and Cabinet went before the Council of State with the recommendation that conditional pardons be granted ex-Queen Liliuokalani, Carl Widemann, Prince "Cupid" and forty-six others. The recommendation received the sanction of the Council of State, and on Friday, September 7th, the prisoners named were released. In releasing the ex-Queen the Government made the extra condition that she reside at Washington Place and not change her residence without permission from the Government; also that she attend no political gatherings nor hold political meetings at her house. Some months later the Government gave the ex-Queen permission to reside anywhere on the Island of Oahu that suited her pleasure.

As Thanksgiving Day approached the friends of the remaining prisoners renewed their efforts to secure the release of the leaders who 'of all those sentenced by the Military Commission were the only ones remaining within the prison walls. Petitions for pardons signed by Hawaiians and foreigners were placed before the President and letters were received from the men in prison in which they admitted their connection with the rebellion, expressed regret for their political mistakes and signified their willingness to take the oath to the Republic, and be numbered among its supporters.

The petitions with the recommendations of the Executive were placed before the Council of State and as a result, on the 28th of November W. H. Rickard, T. B. Walker, and five natives were released from prison upon the same conditions as previous pardons had been granted. There now remained in prison but eight of the men who took part, directly or otherwise, in the revolt. Among this number were R. W. Wilcox, C. T. Gulick, W. H. Seward and J. F. Bowler.

After having released men quite as seriously implicated in the revolt as those who remained in prison, the people of the country were unanimously in favor of the Government making a clean sweep and allowing all the prisoners to go free. The Executive waited, however, until January 1, 1896, when the last prisoners, leaders and all, who had been sentenced by the Military Court were released from prison and allowed to go and come at their pleasure within the country, provided they kept free from political alliances made with a view to attempting the overthrow of the established Government.

This magnanimous policy of the Government toward its former enemies was generally applauded abroad and was received with more or less favor at home, although many of the staunch supporters of the Government believed it the final act of placing the stamp of farcial procedure upon the work of the Military Commission. As to the good or evil effects of the action of the Government upon the peculiar political conditions of Hawaii, time alone will demonstrate. If void of any other results, this action and the fact that it was sanctioned by a good proportion of the men who shouldered guns in support of the Government, shows with what readiness the people of Hawaii forget political differences even though those differences call for the defense of principle by resort to armed force.

Diplomatic Complications

Immediately the Military Court closed its sessions, the foreigners who had been arrested during martial law began to lay plans for obtaining indemnity for what they considered unjust imprisonment. Some of these men had been sentenced by the court but the larger proportion of claimants was among those who had accepted the option of leaving the country and still others who had been arrested during the early days of the revolt and detained in prison until the excited condition of the community had subsided.

The enemies of the Government were quite jubilant over the prospect for a time as it was believed that these claims would result in serious diplomatic complications and condemning the action of the Republic by foreign powers.

The first claims to be heard from by the Government were those of W. H. Rickard and T. B. Walker. These men, of British birth, gave affidavits that they had not become naturalized citizens of Hawaii notwithstanding they had exercised full rights of citizenship and held public office under the monarchy. This claim was regarded by Hawaiian officials as preposterous and upon searching the records it was found that both Walker and Rickard had taken out Hawaiian letters of naturalization. These facts were placed before the British Government and early in August British Commissioner Hawes informed Minister Hatch that the British Government recognized the claim of the Republic as to the citizenship of Rickard and Walker, hence the British Government had no interest in them.

At the request of the British Commissioner his Government had been supplied with the evidence taken at the military trials. Early in August another request was made calling upon the Hawaiian Government to set aside the verdict of the Military Court in the case of V. V. Ashford. The British Government admitted the validity of the court, also that the trials were conducted in an impartial manner. It was held, however, that Mr. Ashford had been convicted upon the evidence of an accomplice, hence the request. The Hawaiian Government took the matter under advisement and up to July 1, 1896, it was still a subject for diplomatic correspondence.

Of those claiming the protection of the British Government who did not appear before the Military Court the following have presented claims that have been brought to the attention of the Hawaiian Government: C. W. Ashford, Fred Harrison, G. Carson Kenyon, Lewis J. Levey, A. McDowall, F. H. Redward, W. I. Reynolds, T. W. Rawlins, E. B. Thomas, M. C. Bailey, and Charles E. Dunwell. Of other nationalities, George Lyeurgus and P. G. Camarinos, citizens of Greece, Edmund Norrie, a Dane, Manoel Gil dos Reis, Portuguese. James Durrell and George L. Ritman, Jr., Americans, have lodged claims for indemnity. The demands of the Grecian Government have been made through Great Britain.

The first case to be urged by the United States was that of James Durrell, an American negro who had been arrested for endeavoring to incite Portuguese to join the ranks of the insurgents. As a result of Durrell's application to his Government the following extraordinary communication was received by the Minister of Foreign Affairs:

The general tenor of this letter, the demand being made before a statement from the Hawaiian Government had been obtained was regarded by the people at large as another evidence of President Cleveland's wholesome dislike for the Republic. The Government, however, took the matter under advisement, made a thorough investigation in order to ascertain the strength of the "prima facie claim" and the case is still the subject of diplomatic correspondence. In fact the evidence taken by the Government in all the cases against those who lodged claims, has been forwarded to the respective governments that have taken up the cause of their injured citizens.

Further evidence of the apparently unfriendly attitude of the United States was found in the release of the schooner Wahlberg, by order of the Secretary of State. The Hawaiian Government held that the act of this American ship conveying the arms to Hawaii for the overthrow of the Republic, was in direct violation of neutrality laws. The American Government took no notice of the claim and released the captain and his ship from custody, notwithstanding the Hawaiian Government had sent an attorney and witnesses to San Diego to aid the prosecution of the case.

Great Britain has pursued a less abrupt course, except possibly in the claim that the verdict in the case of V. V. Ashford should be set aside. The correspondence in this case has not been made public although it is generally understood among the supporters of the Government that the executive officials of the country will not attempt to set aside the action of a court the validity of whose formation and subsequent action has been accepted by Great Britain and upheld by the unanimous decision of the Supreme Court of Hawaii.

The validity of the Military Commission was brought to test before the Supreme Court of the Hawaiian Islands through habeas corpus proceedings to secure the release of J. C. Kalanianaole, "Prince Cupid," convicted of misprision of treason and sentenced to one year's imprisonment at hard labor and to pay a fine of one thousand dollars. The petition was filed May 20, 1895 and the case was argued before the full bench, Chief Justice Judd and Justices Bickerton and Frear, at the special May Term. Paul Neumann appeared for the petitioner and A. S. Hartwell and Lorrin A. Thurston for respondent. No sufficient ground being shown for the discharge of the petitioner he was remanded to the custody of the Government.

The briefs of counsel together with the decision of the court by Justice Frear have been published in book form. The syllabus of the court decision is given as follows:

Shortly after the close of the Military Commission's work the Executive and Advisory Councils passed an Indemnity Act and other laws relating to judicial investigation of claims against the government, sedition and to "persons having certain lawless intentions." These were passed without a dissenting vote and were duly signed by the President. |

|

|

Part 4: Commercial Enterprises Back to Contents Back to History |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |