History of Later

Years

of the Hawaiian Monarchy

|

History of Later

Years of the Hawaiian Monarchy, and the Revolution of 1893 PREFACE Inquiries are continually being made for a brief, clear and dispassionate history of the Revolution of 1893 and of the events that led up to it. The lapse of time has already moderated the bitterness of party spirit, and made it possible to form a juster estimate of the chief actors on both sides of that controversy. A brief sketch of the salient political events of 1887, was written for Col. J. H. Blount at his own request, and afterwards republished by the Hawaiian Gazette Co. At their request the writer reluctantly consented to continue his sketch through Kalakaua's reign and that of Liliuokalani until the eve of the Revolution of 1893, and afterwards to draw up a more detailed account of the revolution and of the subsequent events of that year. The testimony of the principal witnesses on both sides has been carefully sifted and compared, and no pains has been spared to arrive at the truth. The writer, while not professing to be a neutral, has honestly striven not "to extenuate aught or set down aught in malice," but to state the facts as nearly as possible, in their true relations and in their just proportions. The official documents on both sides bearing on the case are given in full, including the report of Col. J. H. Blount to the President of the United States, and the report of the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations, drawn up by Senator Morgan of Alabama. W. D. ALEXANDER

Part 1 The Decadence of the Hawaiian Monarchy

Part 2 Under the Provisional Government

Part 3 History of the Insurrection of January 1895, by Mr. W. R, Farrington

Part 4 Commercial Enterprises of Honolulu

The Reigns of Kalakaua and Liliuokalani It is true that the germs of many of the evils of Kalakaua's reign may be traced to the reign of Kamehameha V. The reactionary policy of that monarch is well known. Under him the "recrudescence" of heathenism commenced, as evinced by the Pagan orgies at the funeral of his sister, Victoria Kamamalu, in June, 1866, and by his encouragement of the lascivious hulahula dancers and of the pernicious class of Kahunas or sorcerers. Closely connected with this reaction was a growing jealousy and hatred of foreigners.

During Lunalilo's brief reign, 1873-74, this feeling was fanned into a flame by several causes, viz., the execution of the law for the segregation of lepers, the agitation caused by the proposal to cede the use of Pearl Harbor to the United States, and the famous mutiny at the barracks. This disaffection was made the most of by Kalakaua, who was smarting under his defeat in the election of January, 8, 1873. Indeed, his manifesto previous to that election appealed to this race prejudice. Thus he promised, if elected, "to repeal the poll tax," "to put native Hawaiians into the Government offices," "to amend the Constitution of 1864," etc. "Beware," he said, "of the Constitution of 1852, and the false teaching of the foreigners, who are now seeking to obtain the direction of the Government, if Lunalilo ascends the throne." Walter Murray Gibson, formerly Mormon apostle and shepherd of Lanai, then professional politician and editor of that scurrilous paper the Nuhou, was bitterly disappointed that he had been ignored in the formation of Lunalilo's cabinet. Accordingly he took the role of an agitator and attached himself to Kalakaua's party. They were both disappointed at the result of the barracks mutiny, which had undoubtedly been fomented by Kalakaua.

Upon Lunalilo's untimely death, February 3, 1874. as no successor to the throne had been appointed, the Legislature was summoned to meet on the 12th, only nine days after his death. The popular choice lay between Kalakaua and the Queen-Dowager Emma. The Cabinet and the American party used all their influence in favor of the former, while the English favored Emma, who was devoted to their interest. At the same time Kalakaua's true character was not generally understood. The natives knew that his family had always been an idolatrous one. His reputed grandfather, Kamanawa, had been hanged, October 20, 1840, for poisoning his wife, Kamokuiki. Under Kamehameha V., he had always been an advocate of absolutism, and also of legalizing the furnishing of alcoholic liquors to natives. While he was postmaster a defalcation occurred, which was covered up, while his friends made good the loss to the Government. Like Wilkins Micawber, he was impecunious all his life, whatever the amount of his income might be. He was characterized by a fondness for decorations and military show long before he was thought of as a possible candidate for the throne. It was believed, however, that if Queen Emma should be elected there would be no hope of our obtaining a reciprocity treaty with the United States. The movement in favor of Queen Emma carried the day with the natives on Oahu, but had not time to spread to the other islands. It was charged, and generally believed that bribery was used by Kalakaua's friends to secure his election. Be that as it may, the Legislature was convened in the old court-house (now occupied by Hackfeld & Co.) and elected Kalakaua King by 39 votes to 6.

A howling mob, composed of Queen Emma's partizans, had surrounded the court-house during the election, after which they battered down the back-doors, sacked the building, and assaulted the representatives with clubs. Messrs. C. C. Harris and S. B. Dole held the main door against them for considerable time. The mob, with one exception, refrained from violence to foreigners, from fear of intervention by the men-of-war in port. The cabinet and the marshal had been warned of the danger, but had made light of it. The police appeared to be in sympathy with the populace, and the volunteers, for the same reason, would not turn out. Mr. H. A. Pierce, the American Minister, however, had anticipated the riot, and had agreed with Commander Belknap, of the U. S. S. Tuscarora, and Commander Skerrett, of the Portsmouth, upon a signal for landing the troops under their command. At last Mr. C. R. Bishop, Minister of Foreign Affairs, formally applied to him and to Major Wodehouse, H. B. M.'s Commissioner, for assistance in putting down the riot. A body of 150 marines immediately landed from the two American men-of-war, and in a few minutes was joined by seventy men from H. B. M.'s corvette Tenedos, Capt. Ray. They quickly dispersed the mob and arrested a number of them without any bloodshed. The British troops first occupied Queen Emma's grounds, arresting several of the ringleaders there, and afterwards guarded the palace and barracks. The other Government buildings, the prison, etc., were guarded by American troops until the 20th.

The next day at noon Kalakaua was sworn in as King, under the protection of the United States troops. By an irony of fate the late leader of the anti-American agitation owed his life and his throne to American intervention, and for several years he depended upon the support of the foreign community. In these circumstances he did not venture to proclaim a new constitution ( as in his inaugural speech he had said he intended to do), nor to disregard public opinion in his appointments. His first Minister of Foreign Affairs was the late Hon. W. L. Green, an Englishman, universally respected for his integrity and ability, who held this office for nearly three years, and carried through the treaty of reciprocity in the teeth of bitter opposition.

The following October Messrs. E. H. Allen and H. A. P. Carter were sent to Washington to negotiate a treaty of reciprocity. The Government of the United States having extended an invitation to the King, and placed the U. S. S. Benicia at his disposal, he embarked November 17, 1874, accompanied by Mr. H. A. Pierce and several other gentlemen. They were most cordially received and treated as guests of the nation. After a tour through the Northern States the royal party returned to Honolulu February 15, 1875, in the U. S. S. Pensacola. The treaty of reciprocity was concluded January 30, 1875, and the ratifications were exchanged at Washington June 3, 1875. The act necessary to carry it into effect was not, however, passed by the Hawaiian Legislature till July 18, 1876, after the most stubborn opposition, chiefly from the English members of the house and the partisans of Queen Emma, who denounced it as a step toward annexation. It finally went into effect September 9, 1876.

The first effect of the reciprocity treaty was to cause a "boom" in sugar, which turned the heads of some of our shrewdest men and nearly caused a financial crash. Among other enterprises the Haiku irrigation ditch, twenty miles in length, which taps certain streams flowing down the northern slopes of East Maui and waters three plantations, was planned and carried out by Mr. S. T. Alexander, in 1877. About that time he pointed out to Col. Claus Spreckels the fertile plain of Central Maui, then lying waste, which only needed irrigation to produce immense crops. Accordingly, in 1878, Mr. Spreckels applied to the cabinet for a lease of the surplus waters of the streams on the northeast side of Maui as far as Honomanu. They flow through a rugged district at present almost uninhabited. The then Attorney-General. Judge Hartwell, and the Minister of the Interior, J. Mott Smith, refused to grant him a perpetual monopoly of this water, as they state it. Up to this time the changes in the cabinet had been caused by disagreements between its members, and had no political significance. In the mean time, Mr. Gibson, after many months of preparation, had brought in before the Legislature a motion of want of confidence in the ministry, which was defeated June 24, by a vote of 26 to 19. On the night of July 1, Messrs. Claus Spreckels and G. W. Macfarlane had a long conference with Kalakaua at the Hawaiian Hotel on the subject of the water privilege, and adjourned to the palace about midnight. It is not necessary to give the details here, but the result was that letters were drawn up and signed by the King, addressed to each member of the cabinet, requesting his resignation, without stating any reason for his dismissal. These letters were delivered by a messenger between 1 and 2 o'clock in the morning. Such an arbitrary and despotic act was without precedent in Hawaiian history. The next day a new cabinet was appointed, consisting of S. G. Wilder, Minister of the Interior; E. Preston, Attorney-General; Simon Kaai, Minister of Finance; and John Kapena, Minister of Foreign Affairs. The last two positions were sinecures, but Kaai as a speaker and politician had great influence with his countrymen. The new cabinet granted Mr. Spreckels the desired water privilege for thirty years at $500 per annum. The opium license and free liquor bills were killed. The actual premier, Mr. Wilder, was probably the ablest administrator that this country has ever had. He infused new vigor into every department of the Government, promoted immigration, carried out extensive public improvements, and at the legislative session of 1880 was able to show cash in the treasury sufficient to pay off the existing national debt. But his determination to administer his own department in accordance with business methods did not suit the King. Meanwhile Gibson spared no pains to make himself conspicuous as the soi-disant champion of the aboriginal race. He even tried to capture the "missionaries," "experienced religion," held forth at sundry prayer meetings, and spoke in favor of temperance.

The professional lobbyist, Celso Caesar Moreno, well known at Sacramento and Washington, arrived in Honolulu November 14, 1879, on the China Merchants' Steam Navigation Company's steamer Ho-chung, with the view of establishing a line of steamers between Honolulu and China. Soon afterwards he presented a memorial to the Hawaiian Government asking for a subsidy to the proposed line. He remained in Honolulu about ten months, during which time he gained unbounded influence over the King by servile flattery and by encouraging all his pet hobbies. He told him that he ought to be his own prime minister, and to fill all Government offices with native Hawaiians. He encouraged his craze for a ten-million loan, to be spent chiefly for military purposes, and told him that China was the "treasure house of the world," where he could borrow all the money he wanted. The King was always an active politician, and he left no stone unturned to carry the election of 1880. His candidates advocated a ten-million loan and unlimited Chinese immigration. With Moreno's assistance he produced a pamphlet in support of these views, entitled "A reply to ministerial utterances."

In the Legislature of 1880 was seen the strange spectacle of the King working with a pair of unscrupulous adventurers to oust his own constitutional advisers, and introducing through his creatures a series of bills, which were generally defeated by the ministry. Gibson had now thrown off the mask, and voted for everyone of the King and Moreno's measures. Among their bills which failed were the ten-million loan bill, the opium-license bill, the free-liquor bill, and especially the bill guaranteeing a bonus of $1,000,000 in gold to Moreno's Trans Pacific Cable Company. The subsidy to the China line of steamers was carried by the lavish use of money; but it was never paid. Appropriations were passed for the education of Hawaiian youths abroad, and for the coronation of the King and Queen. At last on the 4th of August, Gibson brought in a motion of "want of confidence," which, after a lengthy debate, was defeated by the decisive vote of 32 to 10. On the 14th, the King prorogued the Legislature at noon, and about an hour later dismissed his ministers without a word of explanation, and appointed Moreno, Premier and Minister of Foreign Affairs; J. E. Bush, Minister of the Interior; W. C. Jones, Attorney-General; and Rev. M. Kuaea, Minister of Finance.

Moreno was generally detested by the foreign community, and the announcement of his appointment created intense excitement. For the first time the discordant elements of the foreign community were united, and they were supported by a large proportion of the natives. The three highest and most influential chiefs Queen Dowager Emma, Ruth Keelikolani and Bernice Pauahi Bishop joined in condemning the King's course. Two mass meetings were held at the Kaumakapili church, and a smaller one of foreigners at the old Bethel church, to protest against the coup d'ιtat. The diplomatic representatives of the United States, England and France General Comly, Major Wodehouse and M. Ratard raised their respective flags over their legations, and declared that they would hold no further official intercourse with the Hawaiian Government as long as Moreno should be premier. On the side of the King, R. W. Wilcox, Nawahi and others harangued the natives, appealing to their jealousy of foreigners. The following manifesto is a sample :

After four days of intense excitement, the King yielded to the storm. Moreno's resignation was announced on the 19th, and his place filled ad interim by J. E. Bush. On the 30th, Moreno left for Europe, with three Hawaiian "youths" under his charge, viz., R. W. Wilcox, a member of the late Legislature, 26 years of age, Robert Boyd and James K. Booth. It was afterwards ascertained that he bore a secret commission as minister plenipotentiary and envoy extraordinary to all the great powers, as well as letters addressed to the Governments of the United States, England and France, demanding the recall of their representatives. A violent quarrel had broken out between him and his disappointed rival, Gibson who purchased the P. C. Advertiser printing office with Government money. September 1, and conducted that paper thenceforth as the King's organ. Mr. W. L. Green was persuaded to accept the vacant place of minister of foreign affairs September 22. In a few days, he discovered what had been done, and immediately notified the representatives of the three powers concerned of the insult that had been offered them. A meeting was held at his office between the foreign representatives on the one side and himself and J. E. Bush on the other, at which the letters in question were read. The result was that Mr. Green resigned and compelled the resignation of his colleagues.

Mr. Claus Spreckels, who arrived September 5, took an active part in these events and in the formation of the new ministry, which consisted of W. L. Green, Minister of Foreign Affairs; H. A. P. Carter, Minister of the Interior; J. S. Walker, Minister of Finance, and W. N. Armstrong, Attorney-General. Their first act was to annul Moreno's commission, and to send dispatches, which were telegraphed from San Francisco to Washington, London and Paris, disavowing the demands which he had sent. Moreno, however, proceeded on his journey and finally placed the Hawaiian youths, one in a military and two in a naval school in Italy.

The King immediately began to agitate his project of a trip around the world. As it was known that he was corresponding with Moreno, it was arranged that Mr. C. H. Judd should accompany him as Chamberlain, and Mr. W. N. Armstrong as Commissioner of Immigration. He was received with royal honors in Japan, Siam, and Johore. On the King's arrival in Naples. Moreno made an audacious attempt to take possession of His Majesty and dispense with his companions, but he met with more than his match in Armstrong. The royal party visited nearly all the capitals of Europe, where the King added a large number of decorations to his collection, and took particular note of military matters and court etiquette. An Austrian field battery which took his eye, afterwards cost this country nearly $120,000. During the King's absence his sister, Mrs. Dominis, styled Liliuokalani, acted as regent. He returned to Honolulu, October 29, 1881, where he had a magnificent reception, triumphal arches, torches blazing at noonday, and extravagant adulation of every description.

During the King's absence he had kept up a correspondence with his political workers at home, and after his return he produced another pamphlet in Hawaiian, advocating a ten-million loan. Gibson's paper had been filled with gross flattery of the King and of the natives, and had made the most of the smallpox epidemic of 1881 to excite the populace against the ministry. Just before the election of 1882, a pamphlet appeared, containing a scathing exposure of his past career (especially in connection with the Mormon Church), backed by a mass of documentary evidence. Gibson's only reply was to point to his subsequent election by a large majority of the native voters of Honolulu. Only two other white men were elected on the islands that year. It was the first time that the race issue had superseded all other considerations with the native electorate.

The Legislature of 1882 was one of the weakest and most corrupt that ever sat in Honolulu. At the opening of the session Minister Carter was absent in Portugal, negotiating a treaty with the Government of that country. It was soon evident that the Ministry did not control a majority of the House, but the King did. After an ineffectual attempt to quiet Gibson by offering him the Presidency of the Board of Health with a salary of $4000, they resigned May 19th, and Gibson became Premier. His colleagues were J. E. Bush, lately of Moreno's cabinet; Simon Kaai, who drank himself to death; and Edward Preston, Attorney-General, who was really the mainstay of the Cabinet. One of their first measures was an act to convey to Claus Spreckels the crown lands of Wailuku, containing some 24,000 acres, in order to compromise a claim which he held to an undivided share of the crown lands. He had purchased from Ruth Keelikolani, for the sum of $10,000, all the interest which she might have had in the crown lands as being the half-sister of Kamehameha IV., who died intestate. Her claim had been ignored in the decision of the Supreme Court and the Act of 1865, which constituted the crown lands. Instead of testing her right by a suit before the Supreme Court, the Ministry thought it best to accept the above compromise, and carried it through the Legislature. The prohibition against furnishing intoxicating liquor to natives was repealed at this session, and the consequences to the race have been disastrous. The ten-million loan bill was again introduced, but was shelved in committee and a two-million loan act substituted for it. The appropriation bill was swelled to double the estimated receipts of the Government, including $30,000 for coronation expenses, $30,000 for Hawaiian youths in foreign countries, $10,000 for a Board of Genealogy, besides large sums for the military, foreign embassies, the palace, etc. At the last moment a bill was rushed through, giving the King sole power to appoint district justices, through his creatures, the governors, which had formerly been done only "by and with the advice of the Justices of the Supreme Court." This was another step toward absolutism. Meanwhile Gibson defended the King's right to be an active politician, and called him "the first Hawaiian King with the brains and heart of a statesman." At the same time it was understood that Claus Spreckels backed the Gibson ministry and made them advances under the Loan Act.

Kalakaua had always felt dissatisfied with the manner in which he had been sworn in as a King. He was also tired of being reminded that he was not a King by birth, but only by election. To remedy this defect he determined to have the ceremony performed over again in as imposing a manner as possible. Three years were spent in preparations for the great event, and invitations were sent to all rulers and potentates on earth to be present in person or by proxy on the occasion. Japan sent a commissioner, while England, France and the United States were represented by ships of war. The ceremony took place February 12, 1883, nine years after Kalakaua's inauguration. Most of the regalia had been ordered from London, viz., two crowns, a scepter, ring and sword, while the royal feather mantle, tabu stick and kahili or plumed staff, were native insignia of rank. A pavilion was built for the occasion, as well as a temporary amphitheatre for the spectators. The Chief Justice administered the oath of office and invested the King with the various insignia This ceremony was boycotted by the high chiefs, Queen Emma, Ruth Keelikolani and Mrs. Bernice Pauahi Bishop, and by a large part of the foreign community, as an expensive and useless pageant intended to aid the King's political schemes to make himself an absolute monarch, The coronation was followed by feasts, a regatta and races, and by a series of nightly hula hulas, i.e., heathen dances, accompanied by appropriate songs. The printer of the coronation hula programme, which contained the subjects and first lines of these songs, was prosecuted and fined by the court on account of their gross and incredible obscenity.

During this year Mr. J. M. Kapena was sent as Envoy Extraordinary to Japan, while Mr. C. P. laukea, with H. Poor as secretary, was sent to attend the coronation of the Czar Alexander III. at Moscow, and afterwards on a mission to Paris, Rome, Belgrade, Calcutta and Japan, on his way around the world. Kalakaua was no longer satisfied with being merely a King of Hawaii, but aspired to what Gibson termed the "Primacy of the Pacific." Captain Tripp and F. L. Clarke were sent as royal commissioners to the Gilbert Islands and New Hebrides to prepare the way for a Hawaiian protectorate; and a parody on the "Monroe Doctrine" was put forth in a grandiloquent protest addressed to all the great powers by Mr. Gibson, warning them against any further annexation of the islands in the Pacific Ocean, and claiming for Hawaii the exclusive right ''to assist them in improving their political and social condition," i, e., a virtual protectorate of the other groups.

The King was now impatient to have his "image and superscription" on the coinage of the realm, to add to his dignity as an independent monarch. As no appropriation had been made for this purpose, recourse was had to the recognized "power behind the throne." Mr. Claus Spreckels purchased the bullion, and arrangements were made with the San Francisco mint for the coinage of silver dollars and fractions of a dollar, to the amount of one million dollars' worth, to be of identical weight and fineness with the like coins of the United States. The intrinsic value of the silver dollar at that time was about 84 cents. It was intended, however, to exchange this silver for gold bonds at par under the Loan Act of 1882. On the arrival of the first installment of the coin the matter was brought before the Supreme Court by Messrs. Dole, Castle and W. 0. Smith. After a full hearing of the case, the court decided that these bonds could not legally be placed except for par value in gold coin of the United States, and issued an injunction to that effect on the Minister of Finance, December 14, 1883. The Privy Council was then convened, and declared these coins to be of the legal value expressed on their face, subject to the legal-tender act, and they were gradually put into circulation. A profit of $150,000 is said to have been made on this transaction.

Mr. Gibson's first Cabinet went to pieces in little over a year. Simon Kaai was compelled to resign in February, 1883, from "chronic inebriety," and was succeeded by J. M. Kapena. Mr. Peterson resigned the following May from disgust at the King's personal intermeddling with the administration, and in July Mr. Bush resigned in consequence of a falling out with Mr. Gibson. For some time "the secretary stood alone," being at once Minister of Foreign Affairs, Attorney-General and Minister of the Interior ad interim; besides being a President of the Board of Health, President of the Board of Education and member of the Board of Immigration, with nearly the whole foreign community opposed to him. The price of Government bonds had fallen to 75 per cent, with no takers, and the treasury was nearly empty. At this juncture (August 6) when a change of Ministry was looked for, Mr. C. T. Gulick was persuaded to take the portfolio of the Interior, and a small loan was obtained from his friends. Then to the surprise of the public, Colonel Claus Spreckels decided to support the Gibson Cabinet, which was soon after completed by the accession of Mr. Paul Neumann.

Since 1882 a considerable reaction had taken place among the natives, who resented the cession of Wailuku to Spreckels, and felt a profound distrust of Gibson. In spite of the war cry "Hawaii for Hawaiians," and 'the lavish use of Government patronage, the Palace party was defeated in the elections generally, although it held Honolulu, its stronghold. Among the Reform members that session were Messrs. Dole, Rowell, Smith, Hitchcock, the three brothers, Godfrey, Cecil and Frank Brown, Kauhane, Kalua, Nawahi, and the late Pilipo, of honored memory. At the opening of the session the Reform party elected the speaker of the house, and controlled the organization of the committees. The report of the Finance committee was the most damaging exposure ever made to a Hawaiian Legislature. A resolution of "want of confidence" was barely defeated (June 28) by the four Ministers themselves voting on it.

An act to establish a national bank had been drawn up for Colonel Spreckels by a well-known law firm in San Francisco, and brought down to Honolulu by ex-Governor Lowe. After "seeing" the King, and the usual methods in vogue at Sacramento, the ex-Governor returned to San Francisco, boasting that " he had the Hawaiian Legislature in his pocket." But as soon as the bill had been printed and carefully examined, a storm of opposition broke out. It provided for the issue of a million dollars worth of paper money, backed by an equal amount of Government bonds deposited as security. The notes might be redeemed in either silver or gold. There was no clause requiring quarterly or semi-annual reports of the state of the bank. Nor was a minimum fixed of the amount of cash to be reserved in the bank. In fact, most of the safeguards of the American national banking system were omitted. Its notes were to be legal tender except for customs dues. It was empowered to own steamship lines and railroads, and carry on mercantile business, without paying license fees. It was no doubt intended to monopolize or control all transportation within the Kingdom, as well as the importing business from the United States. The charter was riddled both in the house and in the chamber of commerce, and indignation meetings of citizens were held until the King was alarmed, and finally it was killed on the second reading by an overwhelming majority. On hearing of the result, the sugar king took the first steamer for Honolulu, and on his arrival "the air was blue full of strange oaths, and many fresh and new." On second thought, however, and after friendly discussion, he accepted the situation, and a fair general banking law was passed, providing for banks of deposit and exchange, but not of issue.

At the same session a lottery bill was introduced by certain agents of the Louisiana company. It offered to pay all the expenses of the leper settlement for a license to carry on its nefarious business, besides offering private inducements to venal legislators. In defiance of the public indignation, shown by mass meetings, petitions, etc., the bill was forced through its second reading, but was stopped at that stage and withdrawn, as is claimed, by Col. Spreckels' personal influence with the King. Kalakaua's famous "Report of the Board of Genealogy" was published at this session. An opium-license bill was killed, as well as an eight-million dollar loan bill, while a number of excellent laws were passed. Among these were the currency act and Dole's homestead law. The true friends of the native race had reason to rejoice that so much evil had been prevented.

During the next few years the country suffered from a peculiarly degrading kind of despotism. I do not refer to the King's personal immorality, nor to his systematic efforts to debauch and heathenize the natives to further his political ends. The coalition in power defied public opinion and persistently endeavored to crush out or disarm all opposition, and to turn the Government into a political machine for the perpetuation of their power. For the first time in Hawaiian history faithful officers who held commissions from the Kamehamehas were summarily removed on suspicion of "not being in accord" with the cabinet, and their places generally filled by pliant tools. A marked preference was given to unknown adventurers and defaulters over natives and old residents. Even contracts (for building bridges, for instance) were given to firms in foreign countries. The various branches of the civil service were made political machines, and even the Board of Education and Government Survey came near being sacrificed to "practical politics." All who would not bow the knee received the honorable sobriquet of " missionaries." The demoralizing effects of this regime, the sycophancy, hypocrisy and venality produced by it have been a curse to the country ever since. The Legislature of 1884 was half composed of office-holders, and wires were skillfully laid to carry the next election. Grog shops were now licensed in the country districts, to serve as rallying points for the "National party." The Gibsonian papers constantly labored to foment race hatred among the natives and class jealousy among the whites. Fortunately, one branch of the Government, the Supreme Court, still remained independent and outlived the Gibson regime.

The election of 1886 was the most corrupt one ever held in this Kingdom, and the last one held under the old regime. During the canvass the country districts were flooded with cheap gin, chiefly furnished by the King, who paid for it by franking other liquor through the Custom House free of duty, and thereby defrauding the Government of revenue amounting to $4749.35. Out of twenty-seven Government candidates twenty-three were office-holders, one a last year's tax assessor and one the Queen's secretary. There was only one white man on the Government ticket, viz., the premier's son-in-law.

An opium-license bill was introduced towards the end of the session by Kaunamano, one of the King's tools, and after a long debate carried over the votes of the Ministry by a bare majority. It provided that a license for four years should be granted to "some one applying therefor" by the Minister of the Interior, with the consent of the King, for $30,000 per annum. The object of this provision was plainly seen at the time, and its after consequences were destined to be disastrous to its author. Mr. Dole proposed an amendment that the license be sold at public auction at an upset price of $30,000, which, however, was defeated by a majority of one, only one white man, F. H. Hayselden, voting with the majority. Another act was passed to create a so-called "Hawaiian Board of Health," consisting of five kahunas, appointed by the King, with power to issue certificates to native kahunas to practice " native medicine."

The King had been convinced that, for the present, he must forego his pet scheme of a ten-million loan. A two-million loan bill, however, was brought in early in the session, with the view of obtaining the money in San Francisco. The subject was dropped for a time, then revived again, and the bill finally passed September 1. Meanwhile, the idea of obtaining a loan in London was suggested to the King by Mr. A. Hoffnung, of that city, whose firm had carried on the Portuguese immigration. The proposal pleased the King, who considered that' creditors at so great a distance would not be likely to trouble themselves much about the internal politics of this little Kingdom. Mr. H. R. Armstrong, of the firm of Skinner & Co., London, visited Honolulu to further the project, which was engineered by Mr. G. W. Macfarlane in the Legislature. Two parties were now developed in that body, viz., the Spreckels' party, led by the Ministry, and the King's party, which favored the London loan. The small knot of independent members held the balance of power. The two contending parties brought in two sets of conflicting amendments to the loan act, of which it is not necessary to give the details. As Kaulukou put it, "the amendment of the Attorney-General provides that if they want to borrow any money they must pay up Mr. Spreckels first. He understood that the Government owed Mr. Spreckels $600,000 or $700,000. He has lent them money in the past, and were they prepared to say to him, "We have found new friends in England to give him a slap in the face." On the other side, Mr. J. T. Baker " was tired of hearing a certain gentleman spoken of as a second King. As this amendment was in the interest of that gentleman he voted against it." Allusions were also made to the reports that the waterworks were going to be pledged to him. When the decisive moment arrived, the independents cast their votes with the King's party, defeating the ministry by 23 votes to 14. The result was that the cabinet resigned that night, after which Gibson went on his knees to the King and begged to be reappointed. The next morning, October 14, to the surprise of every one and to the disgust of his late allies, Gibson reappeared in the house as premier, with three native colleagues, viz., Aholo, Kanoa and Kaulukou. But from this time on he had no real power, as he had neither moral nor financial backing. The helm of state had slipped from his hands. Mr. Spreckels called on the King, returned all his decorations, and shook off the dust from his feet. The Legislature appropriated $100,000 for a gunboat and $15,000 to celebrate the King's fiftieth birthday. In this brief sketch it is impossible to give any idea of the utter want of honor and decency that characterized the proceedings of the Legislature of 1886. The appropriation bill footed up $3,856,755.50, while the estimated receipts were $2,336,870.42.

From the report of the Minister of Finance for 1888 we learn that Mr. H. R. Armstrong, who had come to Honolulu as the agent of the London syndicate, was appointed agent of the Hawaiian Government to float the loan. He was also appointed Hawaiian Consul-General for Great Britain, while Mr.A. Hoffnung, previously referred to, was made Charge d'Affaires. In the same report we find that the amount borrowed under the loan act of 1886 in Honolulu was $771,800 and in London $980,000. Of the former amount $630,000 was used to extinguish the debt owed to Col. Spreckels. By the terms of the loan act the London syndicate was entitled to 5 per cent, of the proceeds of the bonds which they disposed of, as their commission for guaranteeing them at 98 per cent. But it appears that in addition to this amount 15,000, or about $75,000, was illegally detained by them and has never been accounted for. The Legislature of 1888 appropriated the sum of $5,000 to defray the expenses of a lawsuit against the financial agents, to recover the $75,000 thus fraudulently retained. The matter was placed in the hands of Col. J. T. Griffin, who advised the Government that it was not expedient to prosecute the case. The $75,000 has therefore been entered on the books of the treasury department as a dead loss. Since then Mr. H. R. Armstrong's name has ceased to appear in the Government directory among those of the Consuls-General.

As before stated, the King now acted as his own prime minister, employing Gibson to execute his schemes and defend his follies. For the next eight months he rapidly went from bad to worse. After remaining one month in the cabinet Mr. Kaulukou was transferred to the Marshal's office, while Mr. Antone Rosa was appointed Attorney-General in his place and J. M. Kapena made Collector-General. The limits of this brief sketch forbid any attempt to recount the political grievances of this period. Among the lesser scandals were the sale of offices, the defrauding of the customs revenue by abuse of the royal privilege, the illegal leasing of lands in Kona and Kau to the King without putting them up to auction, the sale of exemptions to lepers, the gross neglect of the roads, and misapplication of road money, particularly of the Queen street appropriation. Efforts to revive heathenism were now redoubled under the pretense of cultivating "national" feeling. Kahunas were assembled from the other islands as the King's birthday approached, and "night was made hideous" with the sound of the hula drum and the blowing of conchs in the palace yard. A foreign fortune teller by the name of Rosenberg acquired great influence with the King.

This was founded September 24, 1886. A charter for it was obtained by the King from the Privy Council, not without difficulty, on account of the suspicion that was felt in regard to its character and objects. According to its constitution it was founded forty quadrillions of years after the foundation of the world, and twenty-four thousand seven hundred and fifty years from Lailai, the first woman. Its by-laws are a travesty of Masonry, mingled with pagan rites. The Sovereign is styled Iku Hai; the secretary, Iku Lani; the treasurer, Iku Nuu. Besides these were the keeper of the sacred fire, the anointer with oil, the almoner, etc. Every candidate had to provide an "oracle," a kauwila wand, a ball of olona twine, a dried fish, a taro root, etc. Every member or "mamo" was invested with a yellow malo or pau (apron) and a feather cape. The furniture of the hall comprised three drums, two kahilis or feathered staffs, and two puloulous or tabu sticks. So far as the secret proceedings and objects of the society have transpired, it appears to have been intended partly as an agency for the revival of heathenism, partly to pander to vice, and indirectly to serve as a political machine. Enough leaked out to intensify the general disgust that was felt at the debasing influence of the palace.

The sum of $15,000 had been appropriated by the Legislature of 1886 towards the expenses of the celebration of His Majesty's fiftieth birthday, which occurred November 16, 1886. Extensive preparations were made to celebrate this memorable occasion, and all office holders were given to understand that every one of them was expected to "hookupu" or make a present corresponding to his station. At midnight preceding the auspicious day a salute was fired and bonfires were lighted on Punchbowl Hill, rockets were sent up, and all the bells in the city set ringing. The reception began at 6 A. M. Premier Gibson had already presented the King with a pair of elephant tusks mounted on a koa stand with the inscription: "The horns of the righteous shall be exalted." The Honolulu police marched in and presented the King with a book on a velvet cushion containing a bank check for $570. The Government physicians, headed by F. H. Hayselden, Secretary of the Board of Health, presented a silver box containing $1,000 in twenty-dollar gold pieces. The Custom House clerks offered a costly gold-headed cane. All officials paid tribute in some shape. Several native benevolent societies marched in procession, for the most part bearing koa calabashes. The school children, the fishermen and many other natives marched through the throne room, dropping their contributions into a box. It is estimated that the presents amounted in value to $8,000 or $10,000. In consequence of the Hale Naua scandal, scarcely any white ladies were seen at this reception. In the evening the Palace was illuminated with electric lights, and a torchlight parade of the Fire Department took place, followed by fireworks at the Palace. On the 20th, the public were amused by a so-called historical procession, consisting chiefly of canoes and boats carried on drays, containing natives in ancient costume, personating warriors and fishermen, mermaids draped with sea moss, hula dancers, etc., which passed through the streets to the Palace. Here the notorious Hale Naua or "Kilokilo" society had mustered, wearing yellow malos and pans or aprons over their clothes, and marched around the Palace, over which the yellow flag of their order was flying. On the 23d a luau or native feast was served in an extensive lanai or shed in the Palace grounds, where 1500 people are said to have been entertained. This was followed by a jubilee ball in the Palace on the 25th. The series of entertainments was closed by the exhibition of a set of "historical tableaux" of the olden time at the Opera House, concluding with a hulahula dance, which gave offense to most of the audience. No programme was published this time of the nightly hulahulas performed at the Palace.

In pursuance of the policy announced in Gibson's famous protest to the other great powers, and in order to advance Hawaii's claim to the "primacy of the Pacific," Hon. J. E. Bush was commissioned on the 23d of December, 1886, as Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to the King of Samoa and the King of Tonga, and High Commissioner to the other independent chiefs and peoples of Polynesia. He was accompanied by Mr. H. Poor, as Secretary of Legation, and J. D. Strong, as artist and collector for the Government museum. They arrived at Apia, January 3d, 1887, and were cordially received by King Malietoa on the 7th, when they drank kava with him and presented him with the Grand Cross of the Order of Oceania. Afterwards, at a more private interview, Bush intimated to Malietoa that he might expect a salary of $5,000 or $6,000 under a Hawaiian protectorate. A house was built for the Legation at the expense of the Hawaiian Government. A convention was concluded February 17th, between King Malietoa and the Hawaiian Envoy, by which both parties bound themselves "to enter into a political confederation," which was duly ratified by Kalakaua and Gibson, "subject to the existing treaty obligations of Samoa," March 20th, 1887. "The signature was celebrated," says Robert Louis Stevenson, "in the new house of the Hawaiian Embassy with some original ceremonies. Malietoa came attended by his ministers, several hundred chiefs ( Bush says 60 ), two guards and six policemen. Laupepa (Malietoa), always decent, withdrew at an early hour; by those that remained all decency appears to have been forgotten, and day found the house carpeted with slumbering grandees, who had to be roused, doctored with coffee and sent home. Laupepa remarked to one of the Embassy, "If you come here to teach my people to drink, I wish you had stayed away." The rebuke was without effect, for still worse stories are told of the drunken orgies that afterwards disgraced the Hawaiian Embassy.

About this time Mr. J. T. Arundel, an Englishman, engaged in the copra trade, visited Honolulu in his steamer, the Explorer, a vessel of 170 tons, which had been employed in plying between his trading stations. The King who was impatient to start his new navy, to maintain "Hawaiian primacy," had put the Reformatory School under the charge of Captain G. E. Jackson, a retired navigating lieutenant in the British navy, with the view of turning that institution into a naval training school. The old Explorer was purchased for $20.000, and renamed the Kaimiloa. She was then altered and fitted out as a man-of-war at an expense of about $50,000, put into commission March 28th, and placed under the command of Captain Jackson. The crew was mainly composed of boys from the Reformatory School, whose conduct, as well as that of their officers, was disgraceful in the extreme. The Kaimiloa sailed for Samoa, May 18th, 1887. On the preceding evening a drunken row had taken place on board, for which three of the officers were summarily dismissed. The after history of the expedition was in keeping with its beginning. As Stevenson relates: "The Kaimiloa was from the first a scene of disaster and dilapidation, the stores were sold; the crew revolted; for a great part of a night she was in the hands of mutineers, and the Secretary lay bound upon the deck." On one occasion the Kaimiloa was employed to carry the Hawaiian Embassy to Atua, for a conference with Mataafa, who had remained neutral, but she was followed and watched by the German corvette Adler. "Mataafa was no sooner set down with the Embassy than he was summoned and ordered on board by two German officers." Another well-laid plan to detach the rebel leader, Tamasese, from his German "protectors" was foiled by the vigilance of Captain Brandeis. At length Bismarck himself was incensed, and caused a warning to be sent from Washington to Gibson, in consequence of which Minister Bush was recalled July 7th, 1887. Mr. Poor was instructed to dispose of the Legation property as soon as possible, and to send home the attaches, the Government curios, etc., by the Kaimiloa, which arrived in Honolulu, September 23d. She was promptly dismantled, and afterwards sold at auction, bringing the paltry sum of $2,800. Her new owners found her a failure as an inter-island steamer, and she is now laid up in the "naval row."

The facts of this case were stated in the affidavit of Aki, published May 31st, 1887, and those of Wong Leong, J. S. Walker and Nahora Hipa, published June 28th, 1887, as well as in the decision of Judge Preston in the case of Loo Ngawk et at., executors of the will of T. Aki vs. A. J. Cartwright et al., trustees of the King. I have already spoken of the opium license law, which was carried by the royalist party in the Legislature of 1886, and signed by the King in spite of the vigorous protests from all classes of the community. As this law had been saddled with amendments, which rendered it nearly unworkable, a set of regulations was published October 15th, 188fi, providing for the issue of permits to purchase or use opium by the Marshal, who was to retain half the fee and the Government the other half. The main facts of the case, as proved before the court, are as follows: Early in November, 1886, one, Junius Kaae, a palace parasite, informed a Chinese rice-planter named Tong Kee, alias Aki, that he could have the opium license granted to him if he would pay the sum of $60,000 to the King's private purse, but that he must be in haste because other parties were bidding for the privilege. With some difficulty Aki raised the money, and secretly paid it to Kaae and the King in three instalments between December 3d and December 8th, 1888. Soon afterwards Kaae called on Aki and informed him that one, Kwong Sam Kee, had offered the King $75,000 for the license, and would certainly get it, unless Aki paid $15,000 more. Accordingly Aki borrowed the amount and gave it to the King personally on the llth. Shortly after this another Chinese syndicate, headed by Chung Lung, paid the King $80,000 for the same object, but took the precaution to secure the license before handing over the money. Thereupon Aki, finding that he had lost both his money and his license, divulged the whole affair, which was published in the Honolulu papers. He stopped the payment of a note at the bank for $4,000, making his loss $71,000. Meanwhile Junius Kaae was appointed to the responsible office of Registrar of Conveyances, which had become vacant by the death of the lamented Thomas Brown. As was afterwards ascertained, the King had ordered a $100,000 gunboat from England, through Mr. G. W. Macfarlane, but the negotiations for it were broken off by the revolution. On the 12th of April, 1887, Queen Kapiolani and the Princess Liliuokalani, accompanied by Messrs. C. P. laukea, J. H. Boyd, and J. O. Dominis, left for England to attend the celebration of the jubilee held upon the fiftieth anniversary of the accession of Her Majesty Queen Victoria. They returned on the 26th of July, 1887.

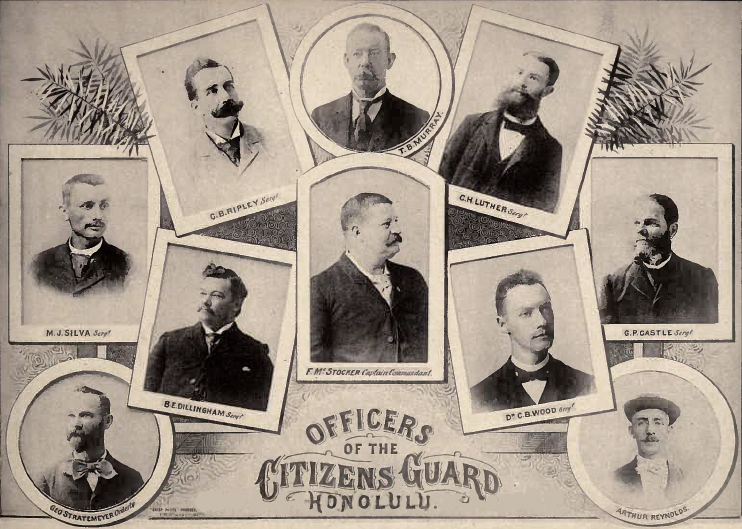

The exposure of the two opium bribes and the appointment of the King's accomplice in the crime as Registrar of Conveyances helped to bring matters to a crisis, and united nearly all tax-payers not merely against the King but against the system of government under which such iniquities could be perpetrated. In the spring of 1887, a secret league had been formed in Honolulu, with branches on the other islands, for the purpose of putting an end to the prevailing misrule and extravagance, and of establishing a civilized government, responsible to the people through their representatives. Arms were imported, and rifle clubs sprang up all over the islands. In Honolulu a volunteer organization, known as the " Rifles," wag increased in numbers, and brought to a high state of efficiency under the command of Col. V. V. Ashford. It is supposed that the league now numbered from 800 to 1,000 men, while its objects had the sympathy of the great majority of the community. It was at first expected that monarchy would then be abolished, and a republican constitution was drawn up. As the time for action approached, the resident citizens of the United Slates, Great Britain and Germany addressed memorials to their respective governments, through their representatives, declaring the condition of affairs to be intolerable. As is the case in all such movements, the league was composed of average men, actuated by a variety of motives, but all agreed in their main object. Fortunately, the "spoils wing" of the party failed eventually to capture either branch of the Government, upon which a number of them joined the old Gibsonian party and became bitter enemies of reform. Some members of the league, including Col. Ashford, were in favor of a sudden attack upon the Palace, but this advice was overruled, and it was decided to first hold a public mass meeting, to state their grievances, and to present specific demands to the King. Accordingly, on the afternoon of the 30th of June, 1887, all business in Honolulu was suspended, and an immense meeting was held in the armory, on Beretania street, composed of all classes, creeds, and nationalities, but united in sentiment as never before or since. The meeting was guarded by a battalion of the Rifles fully armed. A set of resolutions was passed unanimously, declaring that the Government had " ceased through incompetency and corruption to perform the functions and to afford the protection to personal and property rights for which all governments exist," and demanding of the King the dismissal of his cabinet, the restitution of the $71,000 received as a bribe from Aki, the dismissal of Junius Kaae from the land office, and a pledge that the King would no longer interfere in politics. A committee of thirteen was sent to wait on His Majesty with these demands. His troops had mostly deserted him, and the native populace seemed quite indifferent to his fate. He called in the representatives of the United States, Grent Britain, Prance, and Portugal, to whom he offered to transfer his powers as King. This they refused, but advised him to lose no time in forming a new cabinet and signing a new constitution. Accordingly he sent a written reply the next day, which virtually conceded every point demanded. The new cabinet, consisting of Godfrey Brown, Minister of Foreign Affairs ; L. A. Thurston, Minister of the Interior ; W. L. Green, Minister of Finance ; and C. \V. Ashford, Attorney-General, was sworn in on the same day, July 1st, 1887.

As the King had yielded, the republican constitution was dropped, and the constitution of 1864 revised in such a way as to secure two principal objects, viz., to put an end to autocratic rule by making the Ministers responsible only to the people through the Legislature and to widen the suffrage by extending it to foreigners, who till then had been practically debarred from naturalization. I have given the details in another paper. Mr. Gibson was arrested July 1st, but was allowed to leave on the 5th by a sailing vessel for San Francisco. Threats of lynching had been made by some young hot heads, but fortunately no acts of violence or revenge tarnished the revolution of 1887. An election for members of the Legislature was ordered to he held September 12th, and regulations were issued by the new ministry, which did away with many abuses, and secured the fairest election that had been held in the islands for twenty years. The result was an overwhelming victory for the Reform^party, which was a virtual ratification of the new constitution. During the next three years, in spite of the bitter hostility and intrigues of the King, the continual agitation by demagogues, and repeated conspiracies, the country prospered under the most efficient administration that it had ever known.

It has been seen that on the 30th of June, 1887, Kalakaua promised in writing that he would "cause restitution to be made" of the $71,000 which he had obtained from Aki, under a promise that he ( Aki ) should receive the license to sell opium, as provided by the Act of 1886. The Reform cabinet urged the King to settle this claim before the meeting of the Legislature, and it was arranged that the revenues from the Crown lands should be appropriated to that object. When, however, they ascertained that his debts amounted to more than $250,000 they advised the King to make an assignment in trust for the payment of all claims pro rata. Accordingly, a trust deed was executed November 21, 1887, assigning all the Crown land revenues and most of the King's private estate to three trustees for the said purpose, on condition that the complainant would bring no petition or bills before the Legislature, then in session. Some three months later these trustees refused to approve or pay the Aki claim, on which Aki's executors brought suit against them in the Supreme Court. After a full hearing of the evidence, Judge Preston decided that the plea of the defendants that the transaction between Aki and the King was illegal could not be entertained, as by the constitution the King "could do no wrong," and "could not be sued or held to account in any court of the Kingdom.'' Furthermore, as the claimants had agreed to forbear presenting their claim before the Legislature in consideration of the execution of the trust deed, the full court ordered their claim to be paid pro rata with the other approved claims. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |