Natural History of

Hawai`i

SECTION THREE –

FLORA OF THE GROUP

|

Chapter 15: Plant Life of the Sea-Shore and Lowlands The plant life of these highly isolated islands has always been a subject of absorbing interest, and much has been done by botanists since the time of Cook's memorable voyages towards putting a knowledge of the flora into an orderly and systematic form. For those who contemplate a serious study of the vegetation of the islands, the important volume of Dr. Hillebrand's, of course, an essential, but for those who wish merely to know something of the more useful, familiar or conspicuous plants, without going into the subject exhaustively, a brief summary of the more salient features may here suffice. The Island Flora. We have elsewhere had occasion to refer to Hawaii-nei as being so far removed from the mainland of America and the islands of Polynesia that it is indeed difficult to account for the presence of so varied and extensive a fauna and flora. Nevertheless there is no very tangible geologic evidence, aside from the evidence of a deep subsidence, to furnish ground for a belief that the islands in past geologic time have been more closely connected with other lands than they are at present. We therefore have here, if anywhere in the world, a truly virgin flora – one of great tropical beauty and surpassing interest to students as well as to travelers and holiday seekers who ramble off into the mountains and fields or by the sea-shore in search of change from the common place of the city. Those who have studied the matter assure us that the nearest land in the Pacific that can be seriously considered as providing stepping stones that may have been instrumental in giving Hawaii her original stock of plants are the ^Marquesas. But since those islands, like all other lands and islands, are more than two thousand miles distant and are separated from the Hawaiian group by the abysmal depths of the ocean on all sides, the striking physical isolation of the group from adjacent land areas is apparent. Aside from the intercourse that the Hawaiians have had with the groups of islands to the south an intercourse that until recently resulted in the bringing to the group of all of their more important economic plants as elsewhere stated, the flora of the islands once established, seems to have developed naturally and continuously for a very long period of time. The development seems to have been continued to the present time without the complications that elsewhere result from geologic changes, or other disturbing factors either from within or without.

The southeastern, and particularly the southern part of the island, is broken by a number of parallel ridges and valleys. As the valleys are many of them but two or three miles in length the streams, which have their source in the cloud-wrapped peaks that form the dividing line of the island, are cool and beautifully clear. In many of these valleys may still be seen the remains of the old orange and breadfruit groves for which Molokai was one time famous. The heads of the valleys often end in almost vertical and deeply eroded precipices. Several of the valleys, as Moanui, have a number of large caves, which were used extensively in olden times as burial caves.

The valley of Mapulehu is the largest valley on the south side of the island. Having steep funnel-shaped sides and being opposite the great rain-soaked alley of Wailau, it is especially subject to torrential rains.

The nearby harbor of Pukoo, well to the eastern end, and the harbor of Kaunakakai, near the center of the island, are the principal ports of call on the southern side of Molokai. They are both formed by openings in the wide coral reef which extends along the greater part of the island.

The Leper Settlement

Unfortunately the whole of this island of Molokai is known as the "Leper Island." In reality only the low shelf-like promontory of Kalaupapa which jets out into the sea, a distance of three or four miles, at a point about the middle of the island on its northern side, is in any way included in the area set apart by the Territory for the isolation and care of those suffering with this disease.

The settlement forms a colony inhabited by eight hundred to one thousand persons, most of whom are lepers. The colony is completely cut off from the rest of the island by cliffs fifteen hundred or more feet in height, the steep sea-face of which is called Kalawao. The plain or shelf of Kalaupapa is crossed by several lava streams of more recent date than have been found elsewhere on the island. So it is not unlikely that this section, as stated in the legend of Pele previously mentioned, was the last point on Molokai to feel the influence of fires.

Lanai and Kahoolawe

Lanai is in plain view from both Molokai and Maui, being only nine miles west from the nearest point of the latter island.

From the vessel as it passes through the channel between the islands it appears as a single volcanic cone, that doubtless, owing to the protection furnished by the nearby island to windward, has suffered but slight erosion, though its sides are here and there furrowed by small gulches, down one of which there runs a small stream. It has an area of 139 square miles and the principal peak, which is well wooded, is given as 3,400 feet in height. It rises from near the southeastern end and slopes rather gradually to the northwest, where abrupt declivities are found. Steep cliffs also occur along the southwest shore where they are often three or four hundred feet in height. It appears that Lanai nor Kahoolawe have ever been carefully studied by geologists.

Kahoolawe, the smallest of the inhabited islands, is about twelve miles long and has an area of sixty-nine square miles. Owing to its slight elevation, and the fact that it lies in the lee of Maui, whose high mountains wring the rain-clouds dry, the surface shows but little wash and is almost level. There being no important streams or springs on the island it has never been considered of much value. In consequence it has been given over to a few goats, sheep and cattle that roam over its barren red lands at will. Plans have been considered by the Territorial government, however, which contemplate reforesting the island, as an experiment in conservation, with a view to securing scientific data on the increasing and storing of water through the agency of plant growth.

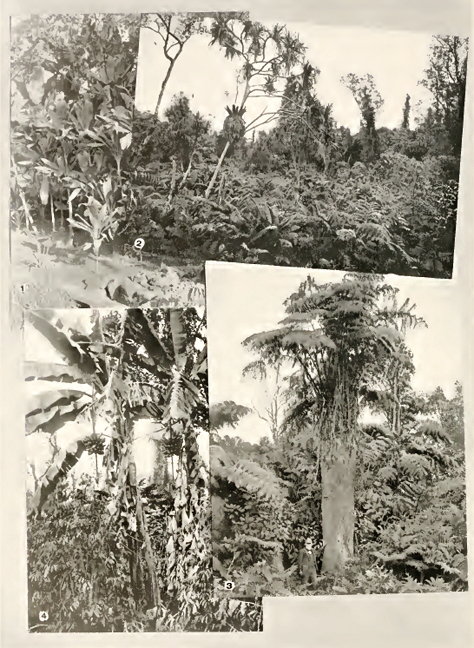

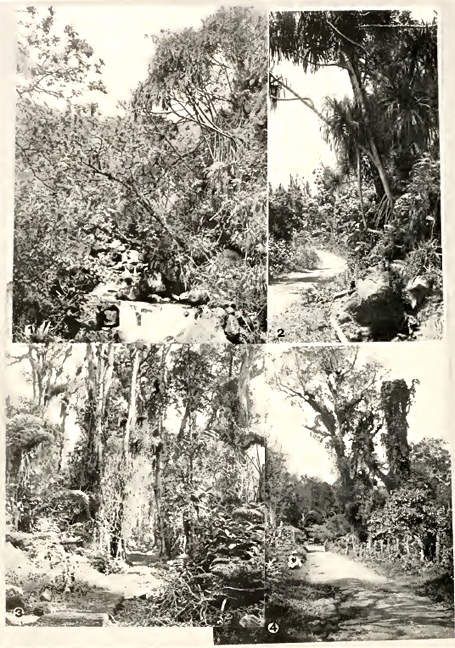

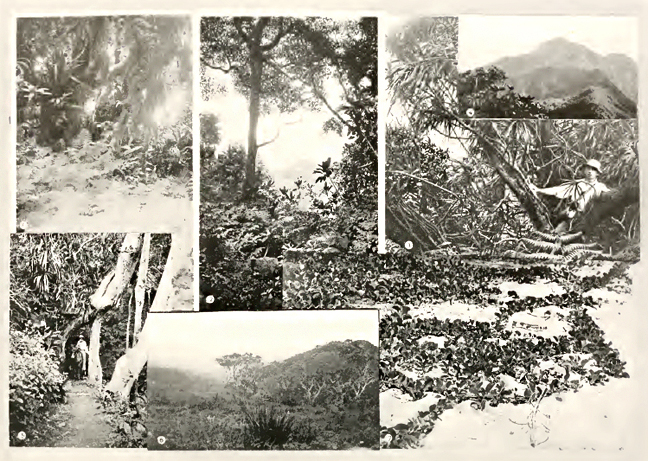

PLATE 50: VEGETATION OF THE LOWER AND MIDDLE FOREST

1. Ki (Cordyline terminalis); the leaves are still used by Hawaiians as a wrapping for food, fish, etc. In former times a strong drink was brewed from the roots. 2. Typical view in a rain forest. In the Lauhala tree (Pandanus odoratissimus) is a bird's nest fern [Ekaha] (Asplenium nidus) in its natural habitat. The Ohia (Metrosideros polymorpha) trees in the background are overrun with Ieie (Freyeinetia Arnotti) while in the foreground several genera of ferns can be recognized among them Sadleria, Cibotium, Aspleniuum, Aspidium, and the like. 3. A famous tree fern [Heii] (Cibotium Menziesii) surrounded by a jungle of Sadleria, Aspidium and other genera of ferns which abound in the moist woods of Hawaii. 4. Wild Bananas [Maia] (Musa sapicutum) and cultivated Coffee (Coffea Arabica) growing in a forest clearing.

Sources Of the movement of ocean currents and their effect as transporting agents, we know but little. Without doubt some plants are transported in this way. As is well known the existing currents in the North Pacific move in a direction that carries them toward the equator from along the shores of the colder American continent. Although Hawaii is in the direct path of this current, few indeed have been the representatives of the North American flora that have been brought to the islands. However, we are not sure that the currents have always had their present motion or direction. It is possible that in by-gone ages, long ago, the movement of the currents of the Pacific may have been reversed, so that various plants from the Australian, Polynesian and South American regions that are well known here, might have been carried to the islands by them, in one way or another. Number of Genera and Species

The ability of birds to make long and direct flights is elsewhere

referred to and without doubt they have been able to bring a small per

cent of the total plant population of the islands. But be that as it may

we find the flora of Hawaii remarkable in that, in proportion to the

entire number of plants, it has more species that are peculiar to the

group than are to be found in any other region of the same area in the

world. If we take the total number of plants, including those which have

been introduced and have become generally naturalized since the coming

of Captain Cook, and include those undoubtedly introduced by the

Hawaiians themselves, we have a grand total, for the native and

introduced flora, of approximately a thousand species of flowering

plants and a trifle over one hundred and fifty species of eryptogamie or

spore-bearing plants, making a list, including recent species, of

perhaps twelve hundred in all. These are divided by Dr. Hillebrand into

three hundred and sixty-five genera, of which three hundred and

thirty-five are flowering plants and thirty are cryptogams. It should be

remembered of course that this number is being added to and altered and

rearranged from time to time, through continued research. It is,

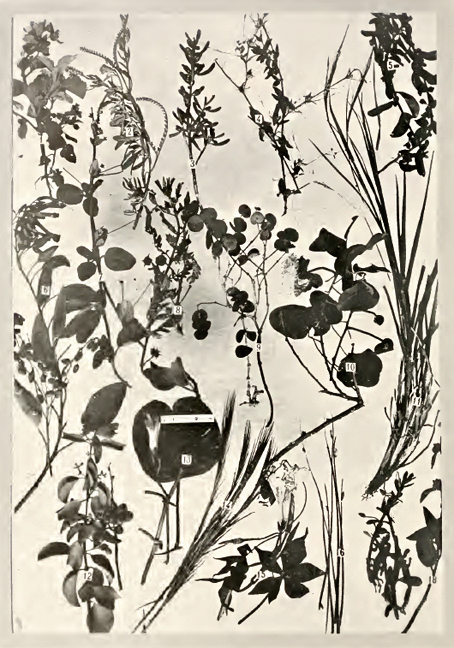

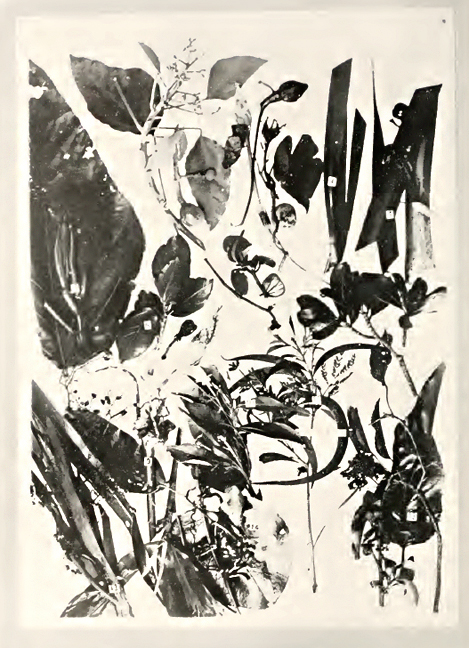

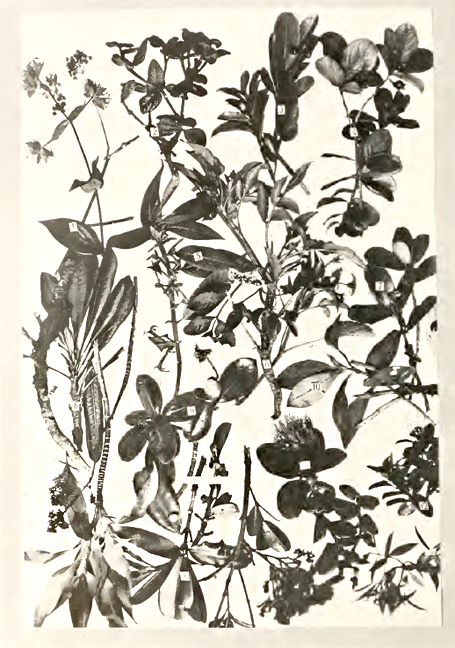

however, sufficiently accurate to indicate the character of the flora. PLATE 51. COMMON PLANTS FROM ROCKY COASTS AND SANDY SHORES

1. Ilima (Sida spinosa), a name applied to several related species. 2.

Beach Heliotrope (Heliotropium Curassavieum). 3. Pickle-weed (Batis

maritima). 4. Alena (Boerhaavia diffusa), Pauohiiaka (Jacquemontia

Sandwicasis). 6. La Platte Tobacco (Nicotiana glauca). 7. Alena (Boerhaavia

diffusa). 8. Nolu (Tribulis cistoides). 9. Akoko (Euphorbia cordata).

10. Maiapilo (Capparis Sandwichiana). 11. Pili (Andropogon = (Heteropogon)

contortus). 12. Beach Sandalwood [Iliahi] (Santalum Freyeinetianum var.

littorale). 13. Beach Morning-glory [Pohnehue] (Ipomoea pes-capra). 14.

Beach grass (Sporobolus Virginicus). 15. Five-fingered Morning-glory [Koali

ai] (Ipomoca tuberculata). 16. Carex sp. 17. Akulikuli (Sesuvium

Portulacastrum). 18. Alaalapuloa (Waltheria Americana). Endemic and Introduced Plants If we exclude from the total list as above given those known to have been introduced by the Hawaiians and Europeans we find over eight hundred and sixty species distributed over two hundred and sixty-five genera that are to be regarded as the original inhabitants of Hawaii. Of this number more than six hundred and fifty species are found nowhere in a natural state outside of Hawaii and are therefore endemic, precinctive or peculiar to the group. The number of endemic plants found on the different islands of the group varies in a way contrary to what might naturally be expected, as the number is largest on Kauai and smallest on the large island of Hawaii. This seems to be in accordance with geologic facts. Since, as has elsewhere been said, Hawaii as a whole is regarded by geologists as the youngest of the islands geologically, it is reasonable to conclude that the number of endemic plants occurring on it, or on any of the islands, furnishes a fair index to the relative age of that particular island. Thus Kauai, which stands fourth in area, stands first in her list of species, and the species are as a rule much better defined than are those on the younger islands of the group. Much that is interesting has been learned by tracing the origin and affinities of the plants of the Hawaiian group. This is done by carefully following out the relationship of the various genera, families and orders with a view to finding if possible the place from which they have been distributed in times past. Since there are no fossil plants in Hawaii it is necessary to rely entirely on the geographical method of determining the source and relationship of the native flora. If the two-thirds of the list of the plants that are found nowhere else be left out of account, we find that the remaining one-third has come from various sources, in many instances far remote from the islands, by routes often difficult to trace. On the other hand there are species that are widely distributed throughout Polynesia that are only allied to American forms. Many others are of Asiatic origin with Polynesian affinities. A small number have been contributed by Australia, while a limited number are of African origin. Si ill other species are almost world-wide in their distribution. Variation in the Flora from Island to Island

The plant life of the several islands of the group not only varies as to

the character of the flora found on each, but each individual island

varies in its flora in different localities to a certain extent, showing

adaptations that accord with variations in altitude, soil, wind and the

amount of rainfall. This is true to such a degree that no two valleys

will have exactly the same plants, and each excursion into the mountains

is liable to be rewarded by bringing to light something not seen

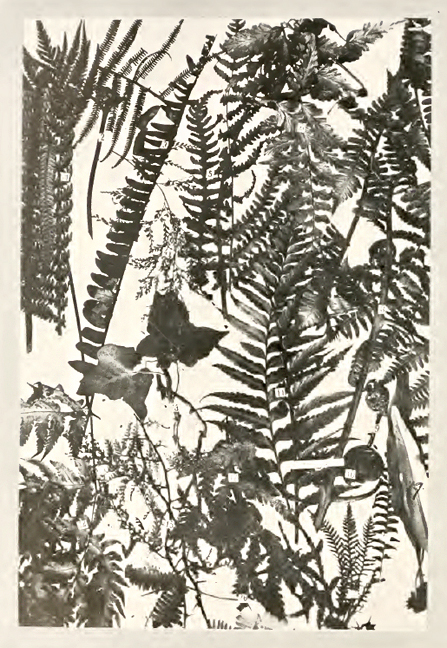

elsewhere and possibly not even known heretofore in the plant world. PLATE 52. STRIKING PLANTS IN THE HAWAIIAN FLORA

1. Hawaiian Mahogany [Koa] (Acacia koa) from the koa forest near the

volcano Kilauea. 2. Tree Ferns (Cibotium sp.) in the fern jungle near

the Volcano House. 3. Lichens on trees; a characteristic of the forests

above 2,000 feet. 4. Lauhala (Pandanus odoratissimus) by the seashore on

Hawaii. 5. Staghorn Fern [Uluhe] (Gleichenia linearis). 6. A Staghorn

Fern tangle near the volcano Kilauea. 7. Wiliwili (Erythrina monosperma).

8. Apeape (Gunnera petaloides), showing the comparative size of its

splendid leaves. Hillebrand and others have found it convenient to group the flora of the islands into different zones based mostly on the elevation they occupy. There are six of these arbitrary zones that with a little experience can easily be recognized since their floras are more or less well defined though, of course, intergrading from one zone to another to some extent. Floral Zones: The Lowland Zone For the purpose of this sketch of the flora of the Hawaiian Islands it will suffice to speak of a few of the more important plants in each zone, beginning at the sea-coast, where there is a peculiar strand vegetation, and from there make an ideal ascent of the mountains, taking one zone after another until the summit of the highest mountains have been explored. Starting with the plants of the lower zone we have species that thrive at the sea-shore, often at the very water's edge. This is known as the littoral flora and always grows along the sea-shore or the margin of brackish water, usually within sound of the sea. It seems to be indifferent to the salt in the soil. Almost all of the plants of this zone are ocean-borne and widely distributed species. As a rule they have fleshy stems and leaves and possess great vitality. They may be uprooted by the waves, borne out to sea by the tides, and carried away for long distances by the currents, to be set out again by the action of the waves on some foreign shore. The plants found growing on Midway, Laysan and Lisiansky, and in fact all the low Pacific islands and shores, are of this littoral type. On Laysan the writer collected twenty-six species that must all owe their origin to the method of transplanting just described. Common Littoral Species

There is very little variation in temperature and conditions at the

sea-shore throughout the group, and as a result we generally find the

condition of plant life fixed and uniform on all of the islands. The

same littoral species may occur wide-spread about the shore of the

different tropical islands, while the genus to which the species belongs

may be represented inland where conditions are more variable by several

species, often one or more such species being peculiar to each island

where the genus occurs. An interesting example of this is found in the

case of the genus Scavola – the naupaka of the natives with a wide

spread shore species. The species of the genus are all small shrubs

bearing white or pale blue and occasionally yellow flowers that are

peculiar in that the corolla is split along the upper side to its base.

Owing to this peculiarity the natives have woven a pretty pathetic story

alb0ut the blossom which tells of how two lovers, who had long been fond

of each other, one day quarreled and parted. As a token of the unhappy

event the maiden tore this flower down the side. This was a sign by

which her sweetheart might know that she loved him no longer, nor would

she care for him until he should find and carry to her a perfect naupaka

flower. The lover went in desperation from one bush to another and from

one island to another searching through the flowers, hoping to find a

blossom that was not torn apart. But alas, he was doomed to

disappointment and it is said that he died of a broken heart. That was

long, long ago; but the naupaka still blooms always with a slit down the

side of the flower, no doubt, as a warning to petulant maidens that it

is unsafe to interfere with the laws of nature. Be that as it may,

through the long ages since (and longer ages before) this shrub has been

blooming on the different islands, and creeping higher and higher into

the mountains, and has slowly adapted itself to the changes of soil,

elevation and climate until several distinct species and a number of

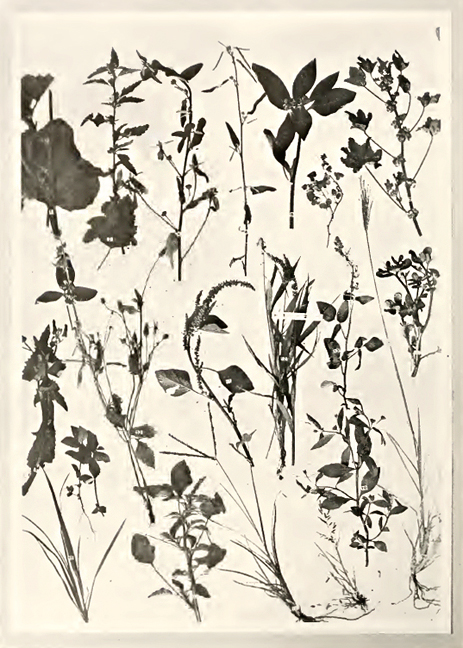

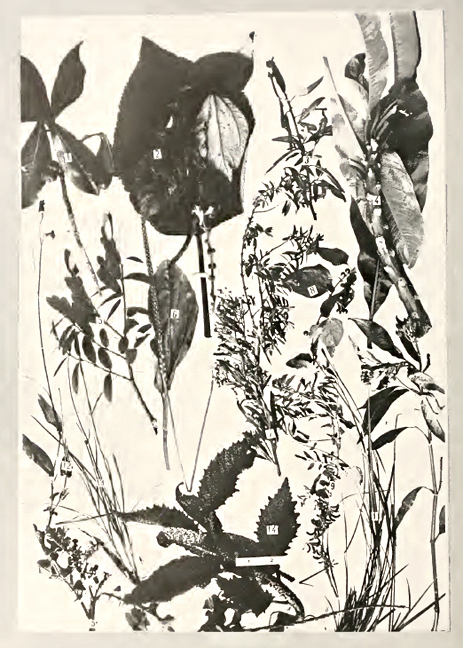

varieties have been formed. PLATE 53. TWENTY COMMON WEEDS

1. Cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium). 2. False Mallow (Malvastrum

tricuspidatum). 3-4. Common Sida (Sida spinosa). 5. Wild Euphorbia

(Euphorbia geniculata). 6. Yellow Wood-Sorrel (Oxalis corniculata). 7.

False Geranium, "Cheeses'' (Malva rotundiflora). 8. Sow Thistle [Pualele]

(Sonchus oleraceca). 9. Rattlebox (Crotalaria sp.). 10. Spanish Needles

(Bidens pilosa). 11. Common Amaranth (Euxolus viridis). 12. Stick-Tight

Grass [Piipii] (Chrysopogon verticillata). 13. Paupilipili (Desmodium

unenatum = Meiobemia uncinatus). 14. Purslane [Ihi] (Portulaca oletacea).

15. Nut Grass [Kaluha] (Kyllingia monocephala. 16. Thorny Amaranth (Amarantus

spinosus). 17. Dog's Tail or Wire Grass (Eleusine Indica). 18. Garden

Grass (Eragrostis major). 19. Eclipta alba, common about taro ponds,

etc. 20. Crow-foot (Chloris radiata). (No number) Garden Spurge

(Euphorbia pilulifera). Another characteristic plant of this zone is the sea morning-glory, the pohuehue of the natives. This species with its thick bright green leaves, lobed at the tip, that grow on thrifty creeping stems which root down from the joints, bears dusky pink flowers familiar to every one who has strolled along the sea shore anywhere in the tropics. A near relative of the above found on the sand beach on lowlands is the native island morning-glory or koali. It is recognized by its heart-shaped leaves and azure blue flowers that become reddish as they fade. The natives used its root in their medicine as a cathartic, and also used it as a poultice for bruises and broken bones.

Associated with these, often growing together with them, is a third

species of morning-glory or Convolvulus, the "koali ai." It is found in

dry rocky soils near the shore and is recognized by its having the

leaves cut into five fingers and its blossoms beautiful purplish-red

flowers. It is of more than passing interest since, as the name implies,

the natives ate its tuberous roots in times of scarcity. They also

wilted and used its .stems for coarse cordage. That the natives should

use this root as food is not so odd as it at first seems when we

remember that the sweet potato or uala, a near relative with more than

twenty varieties was one of the principle sources of vegetable food used

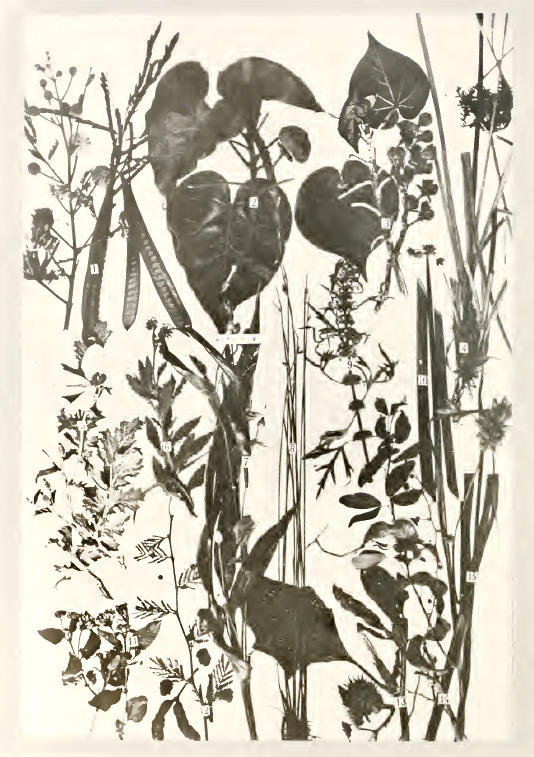

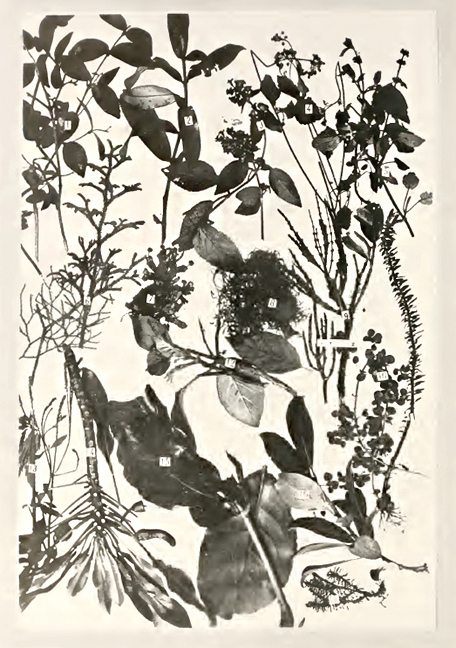

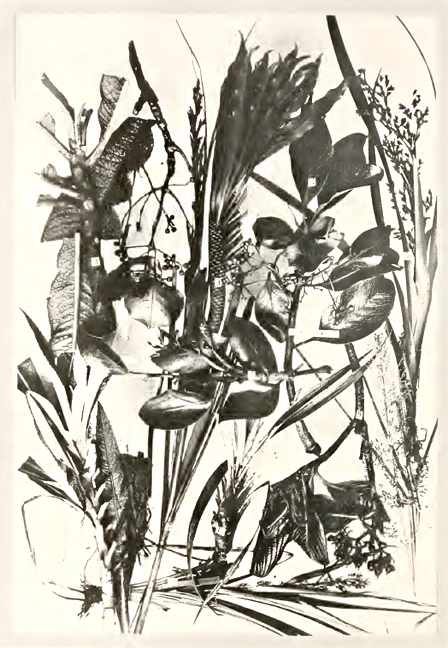

by the natives at the time of the discovery of the islands. PLATE 54. COMMON PLANTS OF THE FIELDS AND ROADSIDE (OAHU)

1. False Koa (Leucana glauca). 2. Kou (Cordia subcordata). 3. Han

(Hibiscus tiliaceus). 4. Galingale (Cyperus pennatus). 5. Mexican Poppy

[Puakala] (Argemone Mexicana). 6. Hinahina (Heliotorpium anomalum). 7.

Job's Tears (Coix lacrymajobi). 8. Sedge (sp. indet). 9. Mint (sp. indet).

10. Bullrush [Akaakai] (Seirpus lacustris). 11. Lantana (Lantana Camara).

12. Kolu (Acacia Farnesiana). 13. Jimson Weed [Kikania] (Datura

Stramonium). 14. "Opium" tree [Opiuma] (Inga dulcis = Pithe-colobium

dulee). 15. Club Rush (Scirpus palustris). Associated with the foregoing is an interesting plant, the kipu kai," one of two species of heliotrope which occurs on the low littoral zone. As the Hawaiian name implies it is invariably found near the sea. Both species, however, usually grow on the raised coral rock or the dry lava flows rather than the sand of the shore. The pure white flowers are in small compact clusters on a low prostrate, wiry stem. The close rosettes of thick silky leaves distinguishes the second species at once from the smooth-leafed larger form with the longer spikes of white flowers. Account of the pickle weed (akulikulikai) should here be taken since it is a common and conspicuous plant in brackish water marshes about Honolulu and Pearl Harbor and one that is rapidly spreading to other localities. Still another plant that is of interest, especially to the small boy, is the nohu. It is sometimes called Mahukona violet by reason of the fragrance of its flowers. The plant is a trailing hairy vine-herb with usually eight pairs of small leaflets to the leaf. The blossoms are yellow and an inch or more across. But the feature of particular interest is the horny seed pods each segment of which is armed with twin spines. The bare-footed boy who steps on one of these pods as it lies buried in the sand is liable to remember the experience for a long time. A common and interesting species in the lowlands along the shore or at the mouths of streams where the water is not too brackish is the akaakai or bulrush with its long, gradually tapering naked stems, three to six feet or more in height. But there are many plants, sedges and grasses in this zone, common on or near the sea-shore of the group, that are all so widespread in their general distribution that they form a list too extensive to receive mention here.

Such plants as the polinalina with the underside of the leaves and

flowers nearly white; the nehe, a low prostrate plant with small, thick,

veinless, silky-haired leaves; the beach sandalwood, a low shrub with

thick, fleshy, pale green leaves; the maiapilo, a straggling shrub with

smooth leaves and large showy many-stamened white flowers; the major

native cotton, a low shrub with hoary white, three-to-five-lobed leaves

and sulphur-yellow hibiscus-like flowers; the pololo or dodder, a

leafless thread-like twining parasite, as well as such trees as the milo

niu, kou, kamani and the noni are all liable to occur at or near the

strand and to attract notice. PLATE 55. VEGETATION IN THE FORESTS, ALONG THE STREAMS AND THE ROADSIDE

1. Typical scene along the mountain streams. 2. On the road to Kilanea.

3. Typical forest jungle in the middle forest zone showing the luxuriant

growth of vines. A fern stem corduroy road leads through the Ohia forest

which is draped with leie vines. To the extreme right and left are

graceful tree ferns, while in the foreground are a number of ferns and

under-shrubs characteristic of the region. 4. View along the Volcano

House road showing a number of introduced plants that have escaped into

the forest. Plants from the Sea-Shore to the Edge of the Forest The second zone begins at the sea-shore and extends back to the lower edge of the forest area and reaches up perhaps a thousand feet or more on the slopes of the mountains. This is termed the lowland zone. It is open country, usually covered with grass after a rain, with isolated trees scattered here and there, representing comparatively few genera. Being either arid, sandy or rocky the region nowhere, except possibly in the valleys and along the windward side produces anything like a luxuriant vegetation. It is in this zone that man has longest had his dwelling and has cultivated, cleared and panted most ; therefore since the coming of foreigners and the extension of irrigation and the cultivation of field crops on a large scale the native plants have all but disappeared from this costal or lowland area. They must now ])e sought in the most unpromising agricultural districts, as about the base of tuff-cones like Diamond Head; or along the lava ledges not accessible to animals ; or better still, on old lava flows too rough or too dry for tillage. One of the most common, persistent and useful of the native trees of this zone is the hau. The tree is very nearly related to the Hibiscus of the gardens from which it can be separated by the fact that in the hau the bracts of the flowers are united to form an eight-to-ten-lobed cup. It is common from the sea-shore to 1,500 feet elevation and is a freely-branching tree growing in a snarl, forming almost impenetrable thickets that sometimes completely fill small valleys. It is a favorite tree with the Hawaiians and is frequently utilized as a shade over arbors and lanais. The light wood served as outriggers for the native canoes, the tough bark made pliable rope, and the bark and flowers were used as an important medicine. The flowers are yellow one day and the next day mauve, and according to Hillebrand double blossoms are occasionally found near the sea-shore.

Very closely related to the foregoing is the milo. Like the hau the

numerous large, showy yellow blossoms make the milo an attractive tree

which often attains a height of forty feet or more. It is somewhat

difficult for the novice to recognize the tree as a distinct species.

The flower bracts, however, are free and only three-to-five in number,

and the seed pods are an inch and a half in diameter, almost as hard as

horn, and hang on the tree long after the seeds have ripened. PLATE 56. KUKUI AND COMMON PLANTS OF THE LOWER FOREST (OAHU)

1. Olona (Touchardia lat ifolia) . 2. Candlenut tree [Kukui] (Aleurites

Moluccana) . 3. Hawaiian Moon Flower (Ipomoea bona-nox). 4. Ieie (Freycinetia

Arnotti). 5. Hala-pepe (Dracaena aurea). 6. Hauhele (Hibiscus

Arnottianus) . 7. Alaal;iwaiiiui (Peperomia sp.). 8. Kopiko (Straevola

Mariniana). 9. Native Ginger [Awapuhi] (Zingiber Zerumbet). 10. Naupaka

(Straevola Chamissoniana) . 11. Koa (Acacia Koa). 12. Kalia (Elaeocarpus

bifidius) with diseased inflorescence. 13. Uki (Dianella ensifol1a). 14.

Uhi (Smilax Sandwicensis). Milo occurs generally over the Pacific islands and was formerly much used by the natives in various ways, but especially in making wooden dishes, calabashes and other household utensils. In many parts of the Pacific the tree is held in religious veneration, being planted in or about the native temples, but this does not seem to have been the case in Hawaii. Two species of native cotton are found in this zone. The one with sulphur-colored flowers is called mao; the one with brick-red flowers is the kokio of the natives. Both species, unfortunately, are rarely met with and the cultivation of either as a garden shrub would be most commendable. In this same region and belonging to the same order as the foregoing are found the four or five species of ilima. They are all low shrubs two to six feet high, with single yellow flowers. The flowers are much prized and have been used for centuries by stringing them together one on top of another on fibers of olona, to make garlands or leis. They are often called the national flower of Hawaii, having long been the favorite flower of Hawaiian royalty. The ohe is also a tree of this region, and though in no way resembling the bamboo, the latter has been given the same name by the natives. It is a low scrubby, thick-trunked tree fifteen to twenty-five feet high growing on exposed open hillsides and is one of the rarer trees of the region. The leaves are a foot long and bear from seven to ten ovate leaflets. These are lost in the winter, the flowers appearing before the leaves in the spring The wiliwili is better known than the foregoing and resembles it in shape and habit. The "coral tree," as it is often called, is to be seen in the city, though unfortunately it is becoming yearly more rare in its native habitat – the open country – where it was formerly a common tree on the rocky hills and plains in the lower open regions on all the islands. The tree rarely grows more than twenty-five feet high and belongs to the bean family, or Leguminosa. It has the trunk and limbs armed with short, stiff thorns. The broad spreading crown of stiff, gnarled, whitish branches bearing bean-like leaflets can hardly escape the attention of the observer; but should it be in flower (its flowers open before the leaves come out) the wealth of red, orange, or yellow blossoms will be a subject of admiration and remark by the merest holiday rambler. The pods are from an inch and a half to three inches in length with from one to several reddish bean shaped seeds a half inch or more in length. It is not to be mistaken for the tree in parks and grounds bearing the small disk-shaped seed called wiliwili or red sandalwoods of tropical Asia, that produces the red lense-shaped "Circassian seeds'" which are curiosities with travelers and used extensively in Hawaii for leis or necklaces. The wood of the wiliwili is very light, said to be lighter than cork, and was much used by the ancient Hawaiians for making the float log of the outrigger for their canoes and also as floats on their fish nets. Another useful plant native to this region, though not well known, is the Hawaiian soap plant or anapanapa which grows to be a large shrub with small greenish flowers. The only really common flowering plant of the islands among the small forms is the Mexican thistle or puakala. It occurs in dry rocky situations on the leeward side of the islands and grows erect and stiff and from two or six feet in height. It boldly displays the large, attractive white terminal flowers that are three inches or more in diameter. Its flowers are amply guarded with a mass of whitish prickly leaves. Though thoroughly naturalized and found by the first collectors, this thistle-poppy was undoubtedly introduced from the warmer parts of North America. One of the most characteristic and abundant native trees of the region, however, is the picturesque Pandanus, better known as lauhala or hala by the natives. It is common on the dry plains and about settlements of the lower regions everywhere, frequently growing down on the sand beach. The stout branching trunks and numerous aerial roots growing out of the trunk, as well as the base of some of the branches, are well known peculiarities of the plant. It has long linear leaves crowded into a head at the end of the branches. The leaves are of great value to the natives, since from them they plait the mats, fans, and other articles, elsewhere described, that are so serviceable. The fibrous wood of the old trees is very hard and capable of taking a high polish and in recent times has been used in making the modern turned wooden bowls or calabashes. Picturesque as the lauhala tree is, its principal charm to the natives is in the bright orange-red fruit from which they will continue to string leis so long as there are natives left to wear them. The base of the fruit contains a small, rich, edible nut – about the only native nut in Hawaii worth eating. The Pandanus occurs widespread over Polynesia. The seeds will stand saturation in sea water for months without losing their vitality. Hence they can be readily transported by ocean currents and planted by sea waves. In addition to the wide geographical range of the plant, geologists tell us that its ancestors were alive and flourishing in the Triassic period in Europe. It is said to be among the oldest and most persistent of plants, and one that in every way is fitted to take part in the pioneer work of starting plant life on a new-born oceanic island; it is therefore strange that it has not been established in some way on the low coral islands of this group. In this same lowland zone occurs the Hawaiian dodder or pololo, a species that also extends its range down to the strand. This curious member of the convolvulus family is a golden yellow leafless parasitic vine that begins life as an herb with a twining stem. When it comes into contact with a suitable tree, shrub or vine it twines itself about it, and at the place where it twines about the host plant it develops suckers which sail from the tree all the nourishment the dodder requires for its growth. Finally the roots of the parasite die and the ignoble plant continues to live on its victim much as the mistletoe does. In various places about the group as in Kau on Hawaii, it covers the bushes and the plant growth over hundreds of acres of the low lands. Introduced Plants As has been said, the region from the seashore up to and above one thousand feet elevation has been most used by man, and as a result the character of the flora has been changed by many plants, both of native and European introduction, that have here found congenial surroundings. A noteworthy example of undoubted Hawaiian introduction is the noni. It is a small tree with stout angular branches clothed with thick, smooth, green leaves six or eight inches long by half as broad. The tree is most easily recognized by its curious potato-like greenish fruits. They are fleshy and juicy, but insipid to the taste, and are very fetid while decaying. The noni occurs all over Polynesia from the strands up several hundred feet in the valleys, and in former times was cultivated as a dye plant by the Hawaiians, who secured a yellow dye from the roots and a pink dye from the bark. With the addition of salt they also secured a blue color that was very permanent. Of the plants that have escaped from European introductions only a few of the more conspicuous or interesting can be mentioned. Next to the lantana perhaps the Verbena or oi, an erect perennial three to six feet high with spikes of small lilac-blue flowers, is one of the most troublesome introductions, especially where large tracts of land are used for pasture. The cassia flower or kolu bean was an early introduction into the islands and grows luxuriantly along the road sides and elsewhere in unproductive regions. Its finely pinnate leaflets and yellow, sweet-scented ball-like flowers are characteristic of this hush, but are no better known to the cross-country rambler than are their sharp needle-like spines. India furnishes tons of the dried blossoms of this plant to commerce, and France, we are told, has plantations devoted to the culture of this or a closely allied species, the aromatic blossoms of which are much used in the manufacture of perfume. Experiments have proven that the quality of the Hawaiian grown flowers, if properly dried, excel in fragrance those grown and cured in India.

Perhaps a dozen species of Acacia are grown in Hawaii, some of which

have established themselves in the open. With these should be mentioned

several species of the genus Cassia, belonging with their cousin the

kolu to the great order of pod-bearing plants that are both wild and

cultivated. PLATE 57. CURIOUS NATIVE PLANTS

1,2,3,6,10. Showing various growth forms of common Lobelias on Oahu. 4. Ferns along the “Olympus” trail on the crest of the ridge at the head of Manoa valley; Konahuanui (3,105 feet) in the distance. 5. Silversword [Ahinahina] (Argyroxiphium Sandwicensis) from Haleakala. 7. Painui (Astelia veratroides) at the volcano Kilauea. 8. Silversword showing the silvery wool on the linear leaves. 9. Ahanui (Cladium Meyenii) at the volcano Kilauea.

Tile nearly related false koa with white ball-like blossoins often an inch in diameter is one that has escaped and become common. Its seeds known as mimosa seeds, are about the size of those of an apple and are used by the natives in making leis and other ornaments for sale to tourists. The wild indigo or iniko of the natives growing two to five feet high with small leaflets in from two to eight pairs to the leaf, is an introduced weed. It was brought in 1836 from Java by Dr. Serriere who, it is said, was able to manufacture a good grade of indigo from it. The species is of American origin, but is now grown in many countries in preference to other indigo-yielding species. This plant is frequently confused with the native plant ahuhu or auholo found growing in the same region and very closely resembling the indigo in size and general appearance. The latter, however, has the flowers and seed terminals on opposite leaves. The pods of the ahuhu are easily recognized, being two inches long and straight, while those of the indigo are a half inch long, much incurved and usually thickly crowded together on the stems. The ahuhu was much used by the natives for stupifying fish, as the plant possesses a narcotic property similar to that of digitalis. It is said to have a similar effect on the action of the heart. The common Vinca, a native of tropical America, has escaped in many places and, as about Halawa on Molokai, flourishes on the rocky hillsides in the open country below the forest line. Black-eyed Susans, or Indian licorice, known to some as prayer beads, has also escaped. The plant has leaflets in seven to ten pairs each about half an inch in length. The flowers are pink or pale purple and are followed by pods an inch or so long filled with scarlet seeds, each with a black spot at the base. The plant probably came originally from Asia, but it is now scattered everywhere. Its seeds, like so many other introduced seeds, are worn in Hawaii in the form of leis. Job's Tears, like the foregoing, no doubt escaped from the gardens of the early missionary settlers and found a congenial soil along the water ponds and waste places in the lowlands. The plant is corn-like in appearance, and the large, white, shining fruits have some resemblance to heavy drops of tears, hence its fanciful name. The plant was originally a native of eastern Asia but is now found everywhere in gardens. With the foregoing should be mentioned the Canna or Indian shot. The common species that has escaped grows along the streams and has been widely scattered about the valleys on the different islands. The flowers are generally red but are frequently yellow and are often variegated as well. The round black seeds are responsible for the English name though the plant is known to Hawaiians as aliipoe. Other species of Canna have escaped, especially on Hawaii, where this genus, which belongs in the same family as the banana, finds conditions especially favorable for its growth. Watercress is in reality a species of Nasturtium. It was an early arrival and has spread in the streams about Honolulu and the islands generally. It is the same species as that so much esteemed as a food in Europe. While it nourishes in Hawaii and is especially tine in flavor, it rarely flowers. The air-plant is another escaped plant. It grows two to five feet tall with erect fleshy stems and large, thick, ovate leaves, and has green bell-shaped nodding flowers tinged with reddish yellow. The air-plant is a familiar species in suitable localities of the lower levels. While it is a native of Africa, it flourishes here and is a well-known curiosity owing to the fact that a leaf left lying on the table will begin to grow from the crenate notches along its edge, apparently deriving its sustenance from the air. Grasses Grasses of various species, both native and introduced, form the principal field vegetation of the coastal region. No fewer than three dozen genera of grasses have been recognized in Hawaii by botanists. Many genera found in the lowlands enjoy a considerable range, extending well up into the mountains, and have numerous species of more or less importance. Of the genus Panicum fifteen species and several doubtful varieties have been recorded by Hillebrand and others. They are found in various places under varying conditions throughout the group. At least a half dozen and perhaps more introduced species belonging to this genus are common in the cultivated districts. The original manienie that formerly occupied the lowlands up to 2,000 feet elevation, belongs to a different genus from the creeping grass introduced in 1835 which is the familiar grass of the yards about the city. The former is a coarser grass creeping with ascending branches six to eight inches long bearing four to eight pairs of leaves. The latter has slender rooting stems, with four to eight pairs of alternate leaves with three to six spikes, an inch or more long, at the end of the stem. Owing to its creeping habit it has been called by the natives manienie. It forms a dense mat in pasture lands and has crowded out other grasses up to the upper limit of the lowland zone. It is of great use in dry, sandy pastures as it binds down the soil and thrives where other grasses fail, since its roots penetrate deep down in the loose soil. Like the algaroba tree, which is a similar fortuitous introduction occupying this zone, it is a most valuable acquisition to the island flora from every point of view. Two species of Paspalum occur in this zone; one, the well-known and generally despised Hilo grass, occurs in moist, heavy soils in the lower zone and grows well into the higher regions in suitable places. The Hilo grass, which is an introduced species as has been said, has crowded out almost every other species of grass where it has gained a foothold. It is a large, rank grass, taller than the native species, growing two to four feet high, and has two spikes at the top of the stem, a peculiarity separating it at once from the similar species having three to six alternately arranged spikes. The well-known pili grass is an important species in this zone, as is also the kakonakona. Two plants, formerly commonly grown in the lower zone by the Hawaiians were their calabash and bottle gourd vines. The calabash gourd is a prostrate climber with lobed leaves and large yellow flowers bearing large depressed globe-shaped red, green or yellow fruits, sometimes two feet or more in diameter. While the original country from which this useful gourd came is unknown, it was common in Hawaii at the time the islands were discovered by Cook, but does not seem to have been known in the rest of Polynesia until after the coming of the white man. As has elsewhere been explained, the hard shell of the ipu nui was made use of as containers for food, water and clothing. The bottle gourd differs from the foregoing in having the leaves undivided, the flowers white and the fruit elongate, often measuring four feet or more in length. The ipu grows on a thrifty musk-scented vine that was largely cultivated by the natives of most tropical countries and, unlike the ipu nui, it was well known all over Polynesia. The hard, woody shell of the fruit served as war masks, bula drums, containers (as water bottles) and in many other ways in the household and general economy of the primitive inhabitants. One of the ingenious arts of the ancient Hawaiians was the ornamentation of these gourds. The gourd to be ornamented was first cleared of the seeds and pulp and then coated on the outside with a thin layer of breadfruit gum, which made it impervious to water. With a sharp instrument, usually the thumbnail, the gum was carefully removed from the part where the pattern, which varied greatly in design, was to show. This done the ipu was buried in taro patch mud for a considerable period. When the color of the soil had become thoroughly set in the shell of the gourd, it was taken from the water and the remaining gum removed, leaving the desired design in two shades of rich brown indelibly dyed in the shell. The Lantana, which belongs in the lower zone, extends its range in many localities up to the three thousand foot level. The common cactus, or panini is the prickly pear of Hawaii, and is common in this region, especially on Oahu. Two species of ilima occur in the lower zone throughout the group. Their bright yellow flowers, so much used in leis, are well known to every one The smaller species is a low shrub, usually with ovate, hairy leaves, and differs from the second species which usually has heart-shaped ovate leaves that are hairy below and greenish above. Both of the foregoing have the leaves rounded at the base, while a third species has the leaves broadest about the middle. In the open edge of the forests, or occasionally descending far down into the lower zone, the ohia lehua is first met with. The ohe seldom reaches the lower forest, while its companion on the fore hills, the wiliwili, seldom reaches the thousand-foot level; but the bastard sandalwood, while it reaches the upper limit of vegetation on the highest mountains, may also occur well down into this lower zone, thus exhibiting a great vertical range in habitat. Back to Contents Chapter 16: Plant Life of the High Mountains Passing now from the lowland zone to the lower forest zone, we find it tropical in appearance. Though not sharply defined it is by common agreement said to begin at about one thousand feet elevation and to extend as a belt about the high mountains up to about three thousand feet. Plants of the Lower Forest Zone The range of the kukui is almost confined to the limits of the lower forest zone, and since it is the most abundant and conspicuous tree of the region, it is regarded as the characteristic tree of the lower forests. The pale green foliage of this useful tree sets it out in marked contrast with the darker greens, and adds a touch of variety to the Hawaiian forest that delights the eye of the beholder. The plants of this region are larger and more thrifty than those of the coastal plain, and being more numerous the open sylvan character of the zone is Well defined. The ki (now commonly written ti) is at home on the steep valley sides and in the gulches, at the lower edge of the forest zone all over the islands, and, indeed, through all Polynesia, the Malayan Archipelago and China. Specimens fifteen feet in height, with leaves from one to three feet in length and three to six or more inches in width, are not uncommon. The ki belongs to the lily order and the leaves are peculiar in having many parallel nerves diverging from a short mid rib. The large saccharine root was made use of in ancient times by the natives in making a curiously flavored beer. Later they learned a method from the sailors of distilling a strong, intoxicating drink from the soaked roots. The ki root was baked by the Hawaiians in their imus (underground ovens, elsewhere described), and eaten by them as a confection; it was their substitute for candy, now so generally eaten by all peoples. The ki root prepared in this way is very sweet, much like molasses candy; it is offered for sale in the market ill Honolulu every Saturday. Among other uses, a stalk with the leaves attached served as a flag of truce in native warfare, and the juice of the plant was used by the Hawaiian belles to stiffen their hair. The leaves, known as la-i or lauki, served and still serve as wrapping. And, since the coming of domestic animals, the plant has proved useful as fodder. Closely related to the ki or ti, belonging to the same order in fact, is the curious halapepe or cabbage tree, sometimes called a palm lily. Its chief interest lies in the fact that it helps to give the foliage that weird character which is expected of tropical verdure. The plant is the largest of the order to which it belongs, often growing twenty-five feet or more in height. It prefers the bold, rugged valley slopes and is a marked tree wherever it occurs. Its thick trunk branches freely and roots are sent out above the ground, so that the tree very much resembles the lauhala in this respect. The leaves, which are two feet or more in length, are born in crowded tufts at the ends of the branches, leaving the trunk and stem rough with leaf scars and marks of slow growth. The botanical name Dracana, meaning a “she dragon,” was given the genus to which the Hawaiian species belongs because of the dragon's-blood resin of commerce which exudes from the bark of certain species, a character shown to some extent by the sap bark of the native species. The old-time Hawaiians carved some of their hideous idols out of its soft, white wood. Another plant peculiar to the lower woods, that extends its range far beyond the line arbitrarily assigned for the upper limit of the zone, is the ieie, a climbing shrub with many of the habits of its cousin, the lauhala. It needs no introduction to the forest rambler. Climbing over the tallest trees or trailing on the ground, it often forms impenetrable thickets. The rigid stem is about an inch in diameter with numerous climbing and aerial roots. The stiff rough leaves, from one to three feet long, are crowded into a tuft at the ends of the stems. The male flowers are on two to four cob-like cylinders five or six inches long by less than an inch in diameter and are surrounded by a whirl of rose-colored leaf bracts. They are among the more showy blossoms of the woodlands. From the pendant roots the natives formerly made ropes of great strength and durability. It is usually at about this elevation that the koa is first met with, though it does not attain its maximum size and importance as a forest tree until well up in the middle forest zone. Hillebrand recognized two closely related species and several varieties; while the cabinet makers, basing their classification entirely on the character of the wood, recognize a dozen or more as curly koa, red koa, yellow koa, and so on, all of which are collectively called Hawaiian mahogany, owing to the superficial resemblance which the wood bears to that well-known cabinet material. Mahogany, by the way, is a native of Central America and the West Indies, and belongs to an entirely different order of plants, of which the introduced Pride of India is an example, but an order of which there are, so far as known, no representatives in the native flora.

The koa is a tree of rare beauty with its laurel-green, moon-shaped,

leaf-like bracts. The tree often attains a height of sixty to eighty

feet, with enormous trunks frequently six to eight feet in diameter, and

with wide-spreading branches. Canoes seventy feet long were made of a

single trunk; it was in such canoes that Kamehameha the Great made his

conquest of this group and contemplated using them in a war-like

expedition to the Society Islands two thousand seven hundred miles

distant. PLATE 58. PLANTS OF THE OPEN FIELDS AND LOWER FORESTS ON OAHU

1. Hoawa (Pittosporum glahrum). 2. Mamake (Pipturus albidus). 3. Kamole

(Jussicra villosa). 4. Lobelia [Ohia wia] (Clermontia macrocarpa). 5.

Akoko (Euphorbia multi- formis). 6. Plantain (Plantago major). 7.

Fleabane or Horse-weed [Hiohe] (Erigeron Canadensis). 8. (Solanum

triflorum). 9. Indigo [Inikoa] (Indigofera Anil). 10. Wild Ipeeae [Nuumele]

(Asclepias Curassavica) . 11. (Carex Oahuensis). 12. Painter's Brush

(Composite Family). 13. Kaluha (Kyllingia obtusifolia). 14. Lobelia (Rollandia

calycina) young. 15. Popolo (Solanum aculcatissomum. (No number) =

Lythrum maritmum. In addition to the many uses made of the wood by the natives in making canoes, calabashes and the like, it has long been esteemed as one of the choice cabinet woods. Combining as it does a rich rod wood, with a beautiful grain that is susceptible of a high polish, it is much used in the manufacture of furniture and as an inside finishing wood in public buildings. The bark is also of use in tanning leather. Botanically the koa belongs to the genus Acacia of which fully half of the known species are Australian, while the rest are scattered widely over the world, many having been introduced into Hawaii. Examples of the native Hibiscus occur, but they are rather rare plants. Four species are known; the flowers are all single and are pink, white, yellow and red respectively. One with ovate leaves and white flowers, often growing twenty-five feet tall, is found in the mountains back of Honolulu and occasionally on the other islands. All of the native species have been held in cultivation as garden shrubs and much has already been done along the line of producing new varieties by cross pollination. A closely allied genus, Hibiscadelphus, has been recently established to include three rare species found on Maui and Hawaii. The native Smilax is by no means the tender hot-house plant one might be led to expect. On the contrary, it is a robust climber with stems a third to a half inch in diameter and fifty feet in length that trail across the forest path. The leaves are three to five inches long and broadly ovate, having a width in proportion. They are easily recognized as they are dark glossy green and have five to seven parallel nerves running lengthwise of the leaf. The natives know this striking vine by various names – uhi, ulehihi and pioi being among them. It is said that they formally ate the tuberous roots in times of scarcity. Another attractive vine of the lower forest zone is the hoi or yam. The scattering large, broad, heart-shaped leaves are five to seven inches long and have from seven to eleven nerves converging towards the tip. It is a plant of wide distribution, extending its range as far as Africa. To the botanist it is of peculiar interest because of the large potato-like bulbs, called alaala by the natives that grow here and there at the base of the leaves. The large, irregular, fleshy roots of the yam were much used as food by the natives, and formerly were cultivated to supply ships calling at Hawaii before the common potato was introduced. The native ginger is a conspicuous and to a certain extent characteristic plant of this zone. Growing one or two feet high with leaves six or eight indies long, and bearing a pretty pale yellow flower on a curious cone-like inflorescence. the awapuhi often entirely covers the ground in the lower forests. The natives made no use of the horizontal fleshy root stocks, but the slimy juice from the inflorescence, being "as slippery as water off an eel was used by the beauty doctors of a former time as a dressing for the hair. This substance, as also the juice of ki, and the sap of the han tree mixed with poi for use in cooling the skin, were three of the chief cosmetics to be found on the dressing table of the Hawaiian belle. The Chinese ginger of commerce is occasionally grown in the islands in a limited way by the Orientals. A number of other species are also grown as ornamental plants. Kauila, or the more widely ranging form known by the same native name, was one of the useful woods of old Hawaii. By reason of its remarkably close, heavy grain it was especially useful in making spears, kapa beaters, and other tools and implements. The second species mentioned was formerly fairly common on the lower slopes of all of the islands, where it formed a tree fifty to eighty feet high with alternate, parallel-veined hairy leaves, and small terminal flowers. The uulai, a low, much-branching, stiff shrub with small leaflets and small white inconspicuous flowers which were followed by whitish roseapple-like fruits, was used for making arrows for the toy bows used in killing rats. The ohia, or ohia lehua, though growing best in altitudes where rain is more abundant, is common and one of the characteristic trees of the lower forest zone. From about 1,500 feet elevation to at least 6,000 and even 8,000 feet, it is an important and abundant tree, to be seen in every landscape. Often it forms dense shaded forests where the trees are festooned with vines and the ground is carpeted with moss and ferns. In such localities trees four feet in diameter and nearly one hundred feet tall are occasionally seen. Unfortunately the root system of this important forest tree is very shallow, often spreading over the surface of the hard soil beneath. As a result they are especially liable to be blown down in the high winds and heavy storms of the higher forest zones. Its wood is very hard and durable, but warps badly. With the coming of the whites it was used to some extent in the framework of their houses and as fence posts. More recently its hard and durable wood has been found to make very excellent railroad ties, street-paving blocks, and it is also much used as a hardwood flooring in dwellings. The ohia occurs on many of the important islands of Polynesia. and its many and intergrading forms long puzzled the native botanists, and it is only fair to say that their European friends have by no means satisfactorily disposed of the problems of classifying the many forms that under varying conditions occur on every island in Hawaii. They may be either trees or shrubs with leaves opposite or alternate, smooth or rough, round or linear, with flowers axillary or terminal, red or rarely yellow; in short any plant in the forest, about which there may be any doubt, is liable to be an ohia or an ohia lehua, though lehua is generally and more correctly the name of the beautiful blossoms which are composed mostly of clusters of the red pistils and stamens.

Of these flowers the natives are both fond and proud. Few indeed are the

mountain climbers that do not return at nightfall decked out with

garlands of the sweet-scented maile and bearing a lei of the beautiful

lehua to the never-forgotten ones at home. PLATE 59. THE MAILE AND ITS PLANT ASSOCIATES ON OAHU

1. Maile (Alyxia olivaeformis) . 2. Akoko (Eiiphorbia clusiaefolia). 3.

Kapana (Phyllostegia grandiflora) . 4. Composite (Sp. indet.). 5.

Phyllostegia sp. 6. Ground Pine [Wawae iole] (Lycopodium cernuum). 7.

Linu Koha (Hepatica). 8. Hepatiea. 9. Hawaiian Mistletoe [Kaumahana] (Viscum

articulatum). 10. Nertera depressa. 11. Wawae iole {Lycopodium

pachystachyou). 12. Cyrtandra sp. 13. Budleya asiatico. 14. Olia wai (Clermontia

persicaeflolia). 15. Papala (Pisonia umbellifera). 16. Kaawau (Byronia

Sandwicensis) . 17. Lycopodium serratum. It is about the modest maile vine that the sweetest perfume and the fondest memories linger. It is of the maile that the voyager first hears as ho hinds in the islands of sunshine and smiles. It is for the maile that he learns to seek on his day-long rambles in the mountains, and it is a braided strand of maile thrown about his neck at the fond parting by the shore that tells with its fresh breath of the enchanted forest, in an enchanted land, and with its lingering caress brings the dew of human tenderness to the eyes of the one departing. And at last it is the faint perfume from a withered half-forgotten keepsake, – a maile lei, that, though the oceans, and half a life time may intervene, will set the heart throbbing and make the eyes grow dim at the memory of the fond aloha that it breathes, calling the wanderer back again to the happiest of lands. The straggling, somewhat twining, inconspicuous maile shrub is common in the woods of the lower and middle regions and is recognized by the elliptical, smooth, oval leaves from one to two inches in length; by the flower which is small and yellowish and by the elliptical, fleshy, black fruits that are more than half an inch long. The maile lei is made from the finer stems which are broken off and the bark removed from the wood by chewing the stems until it will peel off readily. The perfume is not noticeable until the bark has been bruised in this manner. The ohia ai, the mountain apple, or edible ohia, belongs to a different genus, but in the same family as the true ohia. Frequently clumps of the mountain apple will occur surrounded by ohia or kukui, especially at the foot of cliff's, and besides the mountain waterfalls. It is a tree from twenty to fifty feet in height with large green leaves and red flowers followed by refreshing, crimson fruits that grow from the trunk and main branches. The awa is best known owing to the intoxicating drink the Polynesians manufactured from the large, thick, soft woody roots of a plant of the same name which was cultivated by the natives of the various groups of islands of the Pacific. The plant often grows two to four or more feet high, bearing large, alternate heart-shaped begonia-like leaves six inches long by more than that in width. It thrives in Hawaii and was always planted by the natives in the moist valleys of the lower zone. The plants were carefully cared for and the roots when gathered were used either fresh or dried. To make the drink the root, which is astringent to the taste, was first cleaned and thoroughly mixed with saliva. It was then put into a wooden bowl and a quantity of water added. After it had stood a short time the liquid was strained off: it was then ready for drinking. The effect was that of a narcotic and invariably produced stupification if taken in any quantity. Native Fiber Plants The natives formerly cultivated several other plants in the lower forest zone. Olona was one of the most important of these. The plant growls best in regions of great rainfall, usually in the wet forests on the windward side. The olona plant is a low woody perennial, with a viscid .juice, seldom growing more than a dozen feet in height. It has large ovate leaves, often a foot in length and proportionately broad. The genus is a Hawaiian one with but a single species, but botanists tell us that it belongs to the same order as the ramie, which is grown in many places as a fiber plant. The fiber, "olona," is contained in the base of the stem and is remarkably fine and straight and is entirely free from gum. In former times every chief had an olona plantation somewhere in the mountains, as the fiber from the wild plants was not vised to any extent. In raising the crop the ferns were carefully cleared away from about the patch to give the plant all the strength of the soil. The old plants were broken or rolled down to allow the young shoots to grow' straight and rapidly. When of sufficient size the crop was cut, stripped and hackled by the use of crude implements and allowed to dry and bleach until such time as the fiber was white and ready for use. Being resistant to the action of salt water it made fine rope, seines and fish lines. Certain of the natives formerly paid their taxes in olona, and it was always regarded as a valuable possession. The paper mulberry or wauke of the natives has a milky sap and is a small tree with ovate leaves. The leaves are either entire or three-lobed and usually from five to seven inches long, dentate along the edges and roughened on the upper surface. The use and culture of the plant has been explained elsewhere. It is now to be met with growing in clumps here and there through the lower open portions of the forests. Wauke is to be distinguished from the mamake, which is a low shrub seldom over ten feet high, with flowers in auxiliary clusters, that was also used in the manufacture of tapa. Mamake has the ovate leaves three to four inches long, and the sap always watery and the flowers unisexual. The leaves vary greatly in several respects, but generally are whitish beneath. The species seems to be unknown outside of this group. Sandalwood

That portion of Hawaiian history which tells of the discovery of

sandalwood in the islands, and the events which led to its being almost

wiped out as a forest tree as a consequence of its great value in

commerce, may properly be sketched here, since the iliahi furnished the

first article of export which attracted commerce to the islands.

Sandalwood is still occasionally found at rare intervals and in

out-of-the-way places in the lower forest belt on all of the islands,

though the range of the several imperfectly-defined varieties and

species extends the distribution from near the sea shore up to as high

as ten thousand feet on Maui, where the species becomes a low dense

shrub, six to ten feet high. PLATE 60: PLANTS OF THE MOUNTAINS AND ALONG THE SHORE

1. The crest of the Mapulahu-Wailan trail, Molokai (3,151 feet); showing

the character of the growth in the rain forest. 2. View from near the

.summit of the Palolo trail, Oahu; a typical mountain scene. 3. An Ieie

(Freycinetia Arnotti) jungle on Oahu. 4. Typical view of the vegetation

on the mountain ridges of Oahu. 5. A mountain path, showing a natural

graft between two neighboring Ohia trees. 6. Wiew showing the bog flora

at the head of Pelekuku valley, Molokai. 7. Sand beach, showing Pohuehue

(Ipomoca pes-caprae) trailing down to the water's edge. The delicately scented wood is from a tree usually growing from fifteen to twenty-five feet high with opposite ovate to obovate leaves two and a half to three inches long by about an inch and a half in width, which are somewhat thickened and perhaps ochraceous underneath. The flowers occur as small terminal and axillary inconspicuous cymes. The sandalwood trade began about 1792, the first authentic mention of it being made by Vancouver. It is thought that the knowledge of there being sandalwood in the islands was an accidental discovery by one Capt. Kendrick and that the wood was probably brought to his vessel with other timber as fire wood. From this time on the development of the business was rapid until in 1816 it had developed into an important industry among the natives, chiefs and foreigners. Between 1810 and 1825 the trade was at its height. The wood was at first sold in India, but later the market shifted to Canton, where the large pieces were used in manufacturing fancy articles of furniture and in carvings, and the smaller pieces made into incense. For export the green wood was cut in the mountains into logs three or four feet long. These varied from two to eight inches in diameter. The logs were carried on the heads and shoulders of the natives to the shore where they were sorted and tied into bundles weighing one hundred and thirty-three and a half pounds each. While green and wet the wood has no aromatic smell, but when dry the odor is powerful and impregnates the whole atmosphere. The bundles of sandalwood were eagerly purchased by American traders for export. The business flourished to such an extent that it is reported that during the height of the industry three hundred thousand dollars’ worth of sandalwood was exported in a single year.

The king, as well as many chiefs, engaged in this profitable business on

their own account. At about this period each man was required to deliver

to the governor of the district in which he lived one-half “peiul” of

sandalwood or else pay four Spanish dollars. PLATE 61. OHIA AND SOME OF ITS PLANT ASSOCIATES ON OAHU

1. Kadua sp., one of many Hawaiian species. 2. Ohia (Metrosideros rugosa).

3. Ohia ha (Syzygium = (Eugenia) Sandwicensis) . 4. Tall Ohelo (Vaccinium

penduliformis var.). 5. Naupaka (Scaevola mollis). 6. Kokolau (Campylotheca

sp.). 7. Akoko (Euphorbia clusieafolia). 8. Hoawa (Pittosporum.

spatleaIatum). 9. Kopiko (Straussia Kaduana) . 10. Naenae puamelemele (Dubantia

laxa). 11. Ohia lehua (Metrosideros polimiorpha, var.). 12. Metrosideros

polymorpha var. 13. Metrosideros polymorpha var. 14. Metrosideros

tremaloides. 15. Naenae (Dubautia plantaginea). 16. Alani (Pelea

elusiafolia) with tree snail attached to the leaf. 17. Syzygium =

(Eugenia) Sandwicensis with deformed inflorescence. The drain on the supply was enormous. It was not uncommon for lumbering parties of three hundred or four hundred people to go into the mountains. On Hawaii, Ellis relates that he saw two or three thousand men returning from the forest, carrying sandalwood for shipment tied on their backs with ki leaves, each one carrying two or three pieces. Even the roots were dug up in many places. As early as 1831 the business was on the decline, and by 1856 the wood had become very scarce. By 1835 the government recognized the danger of exterminating the valuable trees and steps were taken to prevent the cutting of the young wood. But according to the historian Dibble credit must be given to Kamehameha I for being the first to attempt to conserve the supply of this valuable wood. It is related that the men cut the young as well as the old trees, and that some of the small trees when brought to the shore attracted the great warrior's attention. "Why do you bring this small wood hither?" he inquired. They replied, "You are an old man and wall soon die, and we know not whose will be the sandalwood hereafter." Kamehameha then said, "Is it indeed that you do not know my sons? To them the young sandalwood belongs." Nevertheless, the drain on the forests continued until only an occasional tree was left here and there on the more rugged and inaccessible heights, and even these have suffered from the attacks of wild goats, which find its bark especially toothsome. It is said that the odor of the Hawaiian sandalwood is inferior to that from Malabar, Ceylon, and certain parts of India. The fragrant wood, called laau ala by the natives is quite heavy even after the sap has dried out. It is then a light yellow or pale brown color, and retains the scent indefinitely. While the sandalwood was the most important among the Hawaiian plants producing pleasant odors, it was by no means the only one. There were many others whose flowers, fruits, leaves, sap, bark, wood or roots furnished perfume. The most highly scented of all are the seed pods of the mokihana used in making leis. They are much esteemed as they retain their perfume when dry and hard. The best specimens of this plant, as of almost all the scented varieties of native plants, come from Kauai. For temporary adornment, the leaves and blossoms of wild ginger or awapuhi, the drupe of the lauhala or screwpine, the leaves of the maile and the fronds and stems of several species of ferns, especially the palapalai (a highly scented species) were all used because of their pleasing odors. The scent of the lipoa, a sea moss, was also used as a perfume. Cocoa nut oil, scented with sandalwood, was used to some extent on the hair and body. The bastard sandalwood or naieo is a tree common on the summit of Kaala, and the higher forest belt generally, that becomes fragrant on drying and has an odor that resembles sandalwood. After the exhaustion of the sandalwood it was exported to China for a time as a substitute for that valuable wood. The naieo is found dead in many localities at as low a level as 1,500 feet. In the lower forest region, on Oahu especially, occurs the pretty white-flowered napaka in the form of low shrub. The heads of the valleys in this region are usually marked by clumps of wild bananas, of which there are many varieties, and various species of the interesting and curious Lobelia first appears, and ferns of many species abound. A marked difference exists in the nature of the flora of this zone on the windward or wet and the lee or dry side of the islands, and the student of plant life soon learns that there are many floral districts in this zone, each of which usually has its characteristic species of plants. The Middle Forest Zone The next important area is usually designated as the middle forest zone and extends up the mountains from three to six thousand feet elevation. It is well marked by the greatest luxuriance in tree and jungle. As it is within the region of mist and clouds, it is well watered and furnishes conditions in every way suited to plant growth. It is in this zone that the native Hawaiian flora finds its fullest development. The tree ferns, the giant koa, the ohia and kamani forests are the predominating species. Though none of these larger and more important growths are wholly confined to this region, it is here that they reach their maximum of size and development. On visiting the region one is impressed at once by the number and variety of ferns to be found in this zone. Probably the most important among them are the giant tree ferns, the hapu and hapu ili and the smaller amaumau being the most striking. The hapu with trunks that are from a few inches to three feet in diameter and often fifteen to thirty feet in height are especially abundant about Kilauea and there reach their greatest development. Their plume-like fronds are often fifteen feet or more in length, giving the top a spread of more than twenty-five feet. The native name hapu has been applied to two or three closely allied species. But with the commercial importance the tree gained a few years ago through the use made of the soft, glossy, yellowish wool at the base of the young leaves, these and other large ferns have come to be known as pulu ferns, pulu being the name of the wool-like fiber from the fern. The fiber was used to some extent in stuffing mattresses and pillows, and in a small way as a surgical dressing in cases of excessive bleeding. The old-time natives made use of it in their crude attempts at embalming, human bodies buried in dry caves and elsewhere if wrapped in pulu were liable through absorption by the pulu to dry out or mummify. Giant Ferns Like several other species these giant ferns spring up again from the fallen trunk, particularly in the damp and congenial atmosphere of the middle forest. It is a common sight, along the volcano road, to see the fern stems used for walks and fences continuing their growth, by means of lateral shoots. But space is not sufficient to enumerate all or even the more interesting ferns. Botanists recognize twenty-two genera and at least one hundred and forty good species, more than half of which are confined to the islands. The great majority of these are found most abundantly in the middle forest zone of the different islands of the group. A species of considerable interest is the pala fern. It grows with glossy dark green leaves three to five feet long rising from a thick fleshy root stock. This latter abounds in starch and a mucilagious substance so that when cooked in the native fashion it made a very good food and was much used by the natives in times of scarcity. The bird's-nest fern or ekaha belongs to a large genus that is a widespread form of which there are forty species in Hawaii. The English name is therefore rather loosely applied to any species of the genus. They are common on the trunks and in forks of trees in the forests where they are striking and curious objects resembling birds' nests in many ways. They are much cultivated in the city where specimens with leaves four feet long and eight inches wide are to be seen. The common brake, kilua or eagle fern is everywhere common on all the islands from eight hundred to eight thousand feet elevation, especially on rocky ridges. The species is broken up into many varieties and occurs in one form or another all over the world. The roots of this fern were never used for food. The wild pigs, however, are very fond of them and often turn up great patches in the mountain in search of the roots, thus doing much damage to the forest. The maiden-hair fern or iwaiwa is found in the wet gulches, particularly about waterfalls on all the islands. The black, glossy stems of this fern and also of the larger closely allied species, known under the same name by the natives, was for a time used by them in making hats and baskets, several specimens being preserved in the Bishop Museum.

A conspicuous and serious impediment to travel in this region are the

tangled, forked fronds of the common uluhi or staghorn or one of its two

other closely allied species. The polished brown stem, little larger

than a slate pencil, often grows six feet or more high, forming a tangle

that may extend for miles along the ridges in the whole of the forest

one up to three or four thousand feet elevation. The stems are so tough

and have the fronds so locked together that they often form a barrier

through which it is most fatiguing to force one 's way. PLATE 62. PLANTS FROM NEAR THE SUMMIT OF KONAHUANUI, OAHU

1. Species of Lobelia (Rollandia calyeina) adult. 2. Lapalapa (Cheirodendron

platyphyllum). 3. " Kahili " Lobelia (Cyanea augustifolia). 4. Kawau (Byronia)

Sandwicensis). 5. Ahaniu (Cladium = (Baumea) meyeandra). 6. Typical

Lobelia (Lobelia hypolenea). 7. Gabuia beecheyi. 8. Ohe (Tetraplasandra

meiandra). 9. Kanawau (Broussaisia pallucida). 10. Emoloa (Eragrostis

variabilis). 11. Painui (Astelia veratroides). 12. Rhyuehospora