Natural History of Hawai`i

|

Being an Account of the Hawaiian People, the

Geology and Geography of the Islands, BY WILLIAM ALANSON BRYAN, B. Sc.

Honolulu, Hawai`i, The Hawaiian Gazette Co.,

Ltd. 1915

Professor of Zoology and

Geology in the College of Hawai`i; Fellow of the American Association

for the Advancement of Science; Member, The American Ornithologists

Union; National Geographic Society; American Fisheries Society; Hawaiian

Historical Society; Hawaiian Entomological Society; American Museums

Association; National Audubon Society; Seven Years Curator of

Ornithology in the Bishop Museum, etc.

SECTION ONE – THE HAWAIIAN PEOPLE CHAPTER I: Coming of the Hawaiian Race

CHAPTER 2: Tranquil Environment of Hawaii and Its Effect on the People

CHAPTER 3: Physical Characteristics of the People; Their Language, Manners and Customs

CHAPTER 4: Religion of the Hawaiians: Their Method of Warfare and Feudal Organization

CHAPTER 5: The Hawaiian House: Its Furnishings and Household Utensils

CHAPTER 6: Occupations of the Hawaiian People

CHAPTER 7: Tools, Implements, Arts and Amusements of the Hawaiians

SECTION TWO – GEOLOGY, GEOGRAPHY AND TOPOGRAPHY OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

CHAPTER 8: Coming of Pele and an Account of the Low Islands of the Group

CHAPTER 9: The Inhabited Islands: A Description of Kauai and Niihau

CHAPTER 10: Island of Oahu

CHAPTER 11: Islands of Molokai, Lanai, Maui and Kahoolawe

CHAPTER 12: Island of Hawai`i

CHAPTER 13: Kilauea, the World’s Greatest Active Volcano

CHAPTER 14: Condensed History of Kilauea 's Activity

SECTION THREE – FLORA OF THE GROUP

CHAPTER 15: Plant Life of the Sea-Shore and Lowlands

CHAPTER 16: Plant Life of the High Mountains

SECTION ONE, THE HAWAIIAN PEOPLE

CHAPTER 1: The Coming of the Hawaiian Race

Hawaiians: the First Inhabitants

The Polynesian ancestors of the Hawaiian race are believed to be the first human inhabitants to set foot on Hawaii's island shores. Inasmuch as the group comprises the most highly isolated island territory on the globe, it seems logical to infer that this sturdy race must have migrated to Hawaii from other lands. By tracing the relationship of the original inhabitants it has been found that they belong to the same race as the natives of New Zealand, Samoa, Marquesas, Society, Tonga and other islands in the southern, central and eastern Pacific.

That all the native people found over this vast Pacific region are the scattered branches of one great race, springing from a common ancestral stock, has been demonstrated in many ways. The marked similarity in the manners and customs, language and religion, as well as many peculiar physical characteristics and intellectual traits common to the inhabitants of the widely scattered Pacific islands just mentioned, leaves little doubt in the minds of those who have studied these people of the Pacific, as to their racial affinities.

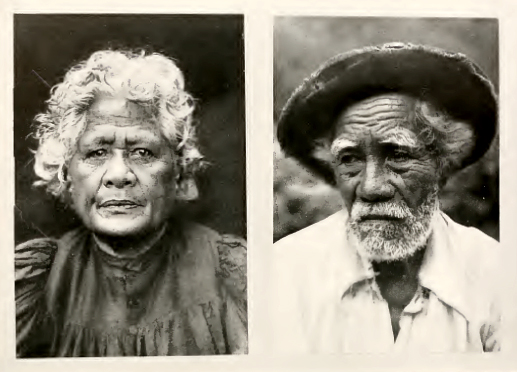

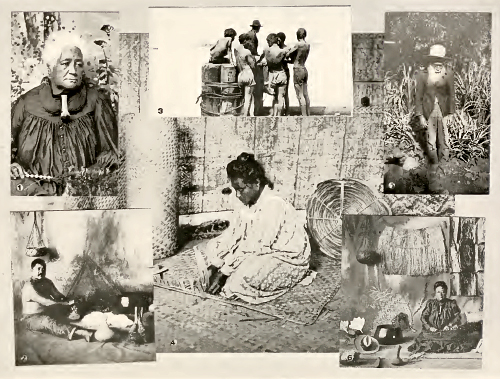

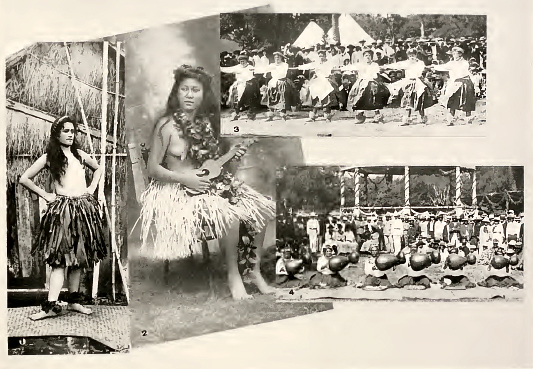

The splendid

physique of the people, their well-shaped heads, attractive features

and kindly eyes are well shown by the photographs and indicate the

strong individuality and lovable character of the race as a whole.

Old Hawaiians, especially of the better class, possessed a high type

of Polynesian culture that embraced a thorough and useful knowledge

of their isolated environment. At the time of their introduction to

European civilization, many among them were intimately acquainted

with their own history and genealogy, as well as with the fund of

information concerning their traditions, myths, arts, occupations

and practices; moreover they possessed a store of knowledge about

the islands and their natural history that at once won for the race

the respect and admiration of their European benefactors.

Polynesian Affinities

Collectively, this group of Pacific Islanders has been called by Europeans the Polynesian Race, a reference to the many islands inhabited by them. The exceedingly vexed question as to the genesis of the race as a whole and the fixing of the place from whence the progenitors of the dark-skinned kanaka people entered the Pacific has long been a subject of interesting discussion.

Since the genesis of the race is by no means a settled question it will not be profitable in this connection to dwell upon the matter farther than to say that the origin of the Polynesian race has been traced by different writers, in different ways to various places. North, South, and Middle America, as well as Papua, Malay, China, Japan and India, have each in turn been declared the cradle of this widely distributed people and each made responsible, directly or indirectly, for their presence in the Pacific Ocean.

While it is probable that the origin of the race, as a whole, will always be shrouded in doubt, there is little uncertainty as to the more immediate ancestors of the Hawaiian people. All their various affinities seem to point unerringly in the direction of the islands to the south of us. Although the Society and Samoan Islands, which are the nearest islands in any direction at present inhabited by this race, are more than two thousand miles distant, they, without doubt, form the stepping stones over which the early immigrants passed—if they are not the actual points of origin of the migrations that resulted in the settling of the Polynesian race on this, the most remote group.

Evidence of Early Immigrations

That the race existed here ages ago, perhaps far beyond the traditions of the people, is believed by some to be proven by certain geologic evidence. Whatever the geological facts may be. and the data thus far secured is by no means conclusive, the traditions of the people are more certain. They throw much light on the antiquity of the early voyages of the race and point far back into the shadowy past. Their genealogies, which were handed down from father to son with remarkable accuracy, also contribute much information that can be accepted as reasonably authentic and historic, and give a fair basis for measuring time, especially during the past four or five centuries. The comparative study of genealogical records has brought to light proof of many obscure points that had to do with the history and wanderings of the race as a whole, but their traditions are especially clear with reference to the Hawaiians themselves.

Traditional and Historical Evidence of Early Voyages

Those who have studied, the history and traditions of the Polynesians as a people regard Savaii, in the Samoan group, as the most likely center of dispersal. It is probable that at least one of the bands of early voyagers that settled on these, then presumably unpeopled islands, came from that group in very ancient times—perhaps as long ago as 500 B.C. Just why these early wanderers set out on the long perilous journey over unknown seas will never be known. It is suggested that they may have been forced from their early homes by war and driven from their course by storms. But since there was no written language, the historian, as already stated, is forced to rely for his data on legends, traditions, genealogies and such other meager scraps of information as are available.

Unfortunately, of the very early period scarcely a reliable tradition exists. We are therefore left free, within a certain measure, to construct for ourselves such tales of adventure, privation and hardship as seem sufficient to account for the appearance of the natives in this far-away and isolated land. We know that the first voyages, like many undertaken in more recent times, must have been made in open boats over an unfriendly and uncharted ocean. We know also that they survived the journey and found the land habitable when they came.

To the dim and uncertain period covering the several centuries that followed, many great primitive achievements have been ascribed. Amongst them are such tasks as the building of walled fish-ponds, the construction of certain great crude temples, the making of irrigation ditches, and the development of a distinct dialect, based of course, on their ancient mother tongue. But at last, after the lapse of centuries, perhaps many centuries, this long period of isolation and seclusion ended and communication was once more resumed with the rest of the Polynesian world. Ancient Voyages It is reliably recorded in the traditions of the race, but more especially in those of the Hawaiian people, that after many generations of separation from the outside world, communication was again taken up and many voyages were made to Kahiki—the far-away land to the south. From this time on the story of the people becomes much more definite and reliable. We not only know that intercourse was resumed between Hawaii and the islands of the South Pacific, but the names of several of the navigators and the circumstances, as well as the time when their journeys were made, also incidents of their voyages, have come down to us. In some cases the same mariner is known to have made more than a single journey. Naturally the exploits of the brave navigators of the race were made matters of record in the minds of the people and handed down from father to son in numberless songs, stories and traditions. As a matter of fact, there is evidence to prove that during the twelfth and thirteenth centuries of our Christian calendar there came an era of great unrest throughout the whole of Polynesia and a great number of voyages were made to the remote parts of the region. In fact it is asserted in the tradition of the people that "they visited every place on earth." This broad statement seems to indicate that to the Polynesian mind the world was confined to Oceanica. as they appear to have known nothing of the great continents which surrounded them on every side. At any rate, there is on record a considerable list of these voyages and an equally long list of the places where they landed, accompanied by incidents of their wanderings.

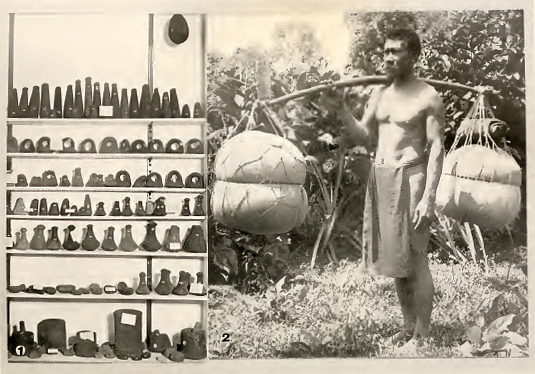

Animals and Plants Brought to Hawaii as Baggage

Our special interest in the natural history of the plants and animals of Hawaii makes this period of Pacific travel of unusual importance. It was at this time that most, if not all, of the useful plants and animals that had followed the race in their various wanderings were brought as precious baggage with them to these islands from over the sea.

Any one who has experienced the difficulties and disappointments encountered in transplanting a young breadfruit tree from one valley to another, will appreciate in a measure the difficulties that must of beset the Hawaiians in transporting living cuttings of this delicate seedless plant from far off Kahiki to these islands, yet it is practically certain that not only was the breadfruit brought here in this manner but also the banana, the taro, the mountain apple, the sugar-cane and a score or more of their other important economic plants. The wild fowl, the pig and the dog were also brought with them in the same way, in very early times, and were in a state of common domestication over the group when the islands were first visited by the white race.

Naturally there were many references in Hawaiian and Polynesian tradition to these long and tempestuous voyages. When all the circumstances surrounding these rugged feats of daring and adventure are considered, it is not too much to say that the race to which the ancient Hawaiians belonged is worthy of a special place among the most daring and skillful navigators of all times. To this day their prowess and aptitude in matters pertaining to the sea is such as to command the admiration and respect of all.

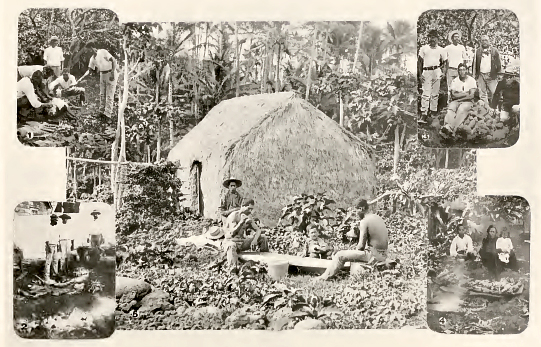

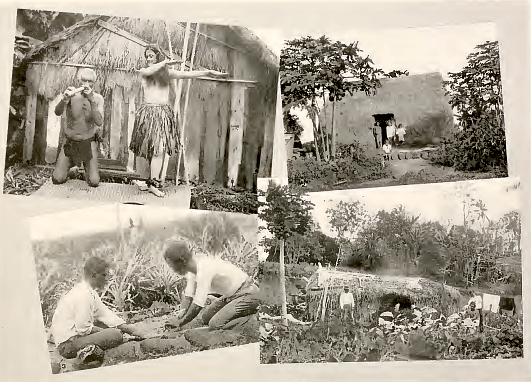

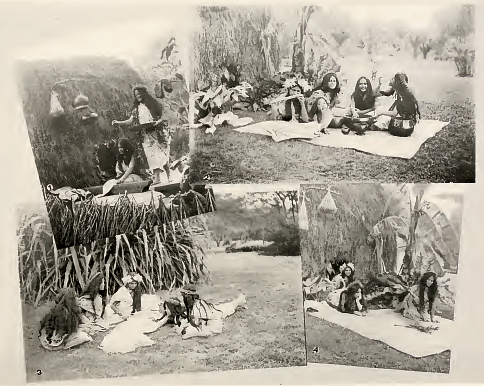

PLATE 2: HAWAIIAN GRASS HOUSE WITH TYPICAL SETTING

The house shown is in a valley near the stream and is surrounded by a few useful trees and plants, including the cocoanut, mountain apple, banana and taro. The small terraced taro ponds nearby are supplied with water drawn by ditches from the swift, rocky stream. In the extreme distance, the valley is crossed by a trestle carrying a modern irrigation flume.

Double Canoes.

The making of the large canoes employed in their important journeys by the use of stone tools alone, was by no means an ordinary task. Aside from the descriptions of their canoes handed down to us in their traditions, we know that a century ago there existed in these islands the remains of war canoes, such as we are told were used in those early voyages, that were seventy feet in length by more than three feet in width and depth, capable of carrying seventy persons from island to island. What is still more remarkable the hull in each case was carved from a single giant koa log.

The selecting of a suitable tree from among its fellows in the mountain forests, the felling and shaping of it by means of the crude stone implements of the time, and the subsequent transporting of the rough-hewn canoe to the sea by main strength, was an undertaking not to be lightly assayed; but the executing of a 2,000-mile voyage in such a craft seems almost incredible. In this connection it is well to remember that the early Polynesians made not only single canoes of monstrous proportions, but double ones by lashing two together and rudely decking over the space between them. In this ingenious way they made a craft capable of carrying a large number of people and a goodly supply of provisions.

Provisions for Long Voyages.

It is probable that in their more extended voyages, especially when they were voluntarily undertaken, the natives used the double canoe and provided the craft with a mast to which they rigged durable sails made of mats. The legendary mele telling of the coming of Hawaii-loa states that during live changes of the moon he sailed in such a craft to be rewarded at last by the sight of a new land ever after called Hawaii.

As to the supply of provisions it is to be remembered that the Polynesians have several kinds of food capable of being preserved in a compact form. The cocoanut, either fresh or dried, was an invaluable article of food, while dried fish and squid are not to be despised. The taro, breadfruit and sweet potato, or yam, are articles of daily diet, capable of being transported in an edible condition for great distances at sea. Besides cocoanut water, in the nut, to drink, they had utensils for storing fresh water and it is probable that they provided themselves with calabashes and wooden bowls specially prepared for use on their long sea journeys.

Steering a Course by the Stars

As they were expert fishermen and exceedingly hardy seamen the perils of the deep were considerably minimized. Add to this their intimate knowledge of the food to be found living everywhere in the sea at all seasons and their acquaintance with the habits and methods of capture, as well as skill in the preparation of such animals and plants as they esteemed as food, and we must conclude that they were by nature well fitted for such journeys. With such substitute food as the sea would furnish, always at hand, it was possible for them to travel far and suffer but little, for they were able to eat, not only such fresh and dried food as we have mentioned, but to relish many creatures of the sea in a raw state—as flying-fish, squid and seaweed—that would scarcely be thought of as food by a more fastidious people. Moreover, in making these journeys they were able to roughly guide their course by the stars, the sun and the moon, as they had a crude but working knowledge of astronomy. In addition to this they had a number of traditions, telling of mysterious lands, far away beyond the horizon, that served them both as an inspiration and an assurance, besides being useful to them in many ways in their practical navigation.

Establishment of the Hawaiian Race

Great care was always exercised in selecting the proper place and season for setting forth on their journeys. Once having made a successful voyage they were particular to start from the same spot in making similar journeys thereafter. In this way the south point of Hawaii as well as the southern end of the little island of Kahoolawe came to be known as the proper points from which to embark on a journey to Tahiti.

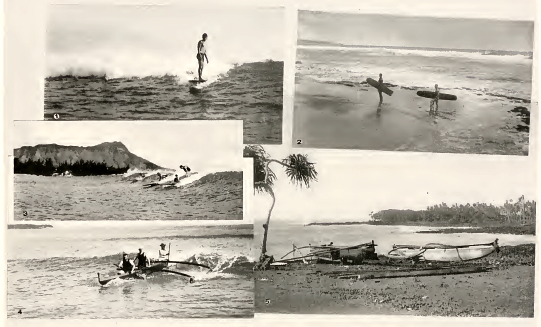

There is but little doubt that in those times they were expert navigators, who in addition to being able to guide their courses at sea by the stars, also knew the art of steering their canoes in such a fashion as to catch and ride great distances on the splendid long ocean swells, after the manner of the surf riders of less adventurous times.

Just how these striking feats of navigation were accomplished we may never know. At any rate there is every reason to believe that they were performed. We do know, however, that the perils attending them were safely passed, the difficulties of the journeys surmounted, and that those who performed them lived to tell the tale of their daring to their children, and they to their children's children. We know that through them in time the Polynesian race came to occupy a new land, established the Hawaiian people and built up a crude though worthy civilization. Back to Contents

The Natural Environment.

Without dwelling further on the remote and uncertain period which had to do with the origin and early migration of the Hawaiian people, it will be fitting to briefly consider the race in connection with their natural environment. It is well within the purpose of this sketch of the natural history of Hawaii to treat of the people as the native inhabitants, and for that reason we shall dwell upon their primitive and interesting native culture rather than their more recent political history.

In dealing with the race as a natural people it will be of interest to enumerate some of the various forces of nature among which they developed for centuries, since without doubt their environment helped to make the race what it was at the time of its discovery,—a swarthy, care-free, fun-loving, superstitious people, with a culture that, now it has been more fully studied by unbiased ethnologists and is better understood, has at last gained for the ancient Hawaiians, not only the respect, but the admiration of their more highly-cultured and fairer-skinned brothers.

Kona Weather and Trade Winds

One of the most important physical influences that has affected the people is the climate. Although the Hawaiian Islands lie at the northern edge of the torrid zone, their climate is semi-tropical rather than tropical, and is several degrees cooler than that of any other country in the same latitude. The temperature is moderate, at least ten degrees below the normal owing to the influence of the cool northeast ocean currents. The delightfully cool northeast trade wind, which is obviously the principal element in the Hawaiian climate, blows steadily during at least nine months of the year. During the remaining months the wind is variable, and occasionally storms with heavy rains that blow from the southwest, producing what is known as "Kona" (Southerly) weather. Taken through a long period, the temperature at sea level rarely rises above 90 degrees during the hottest day of the year, and seldom falls below 60 degrees for more than a few hours at a time, with the mean temperature fluctuating about 75 degrees Fahrenheit. The difference between the daily average midsummer and midwinter temperature is about 10 degrees. With reference to human comfort the temperature excels for its equableness. This fact, coupled with the refreshing trade winds that sweep over thousands of miles of cool ocean and the bright and genial warmth of the tropical sun, produces the climate of Paradise—a condition found in no other region on the globe.

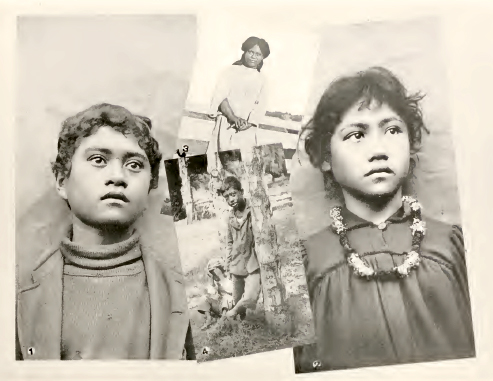

1. Hawaiian boy

with wavy hair. 2. Hawaiian girl with straight hair; the holoku or

dress is of a style introduced by the early missionaries; the lei of

necklace of flowers is of introduced red and white carnations. 3. &

4. Typical children of the country villages.

Altitude and Its Effect on Climate

In fact the Hawaiian language had no word for "weather," as it is usually understood. Nevertheless, a remarkable difference in climate is experienced in passing from one side of the islands to the other, or from lower to higher altitudes. The northeast, or windward side of the group, which is exposed to the trade winds, is cool and rainy, while the southwestern or leeward side is, as a rule, much drier and warmer. The most important variation, however, is due to altitude; the thermometer falling about four degrees for every 1,000 feet of ascent. It is therefore possible to look from the palm groves that bask in tropical warmth along the coast of Hawaii to the highest mountain peak of the group (Mauna Kea, 13,825 feet) to find it frequently snow-capped, particularly during the cooler months. As to rainfall, similar variations occur. At Honolulu the average precipitation is thirty-eight inches, at the Pali, five miles away in the mountains, 110 inches; while at Hilo, on the north side of Hawaii, it is nearly twelve feet. If the group is taken as a whole, almost every variation from warm to cold, wet to dry, windy to calm, may be found.

Effect of a Sufficient Amount of Food

The direct influence of these facts on the character of the people, however, is rather obscure. Aside from the bearing it may have had on their clothing, food and shelter it is indeed difficult to trace. Although it is the general opinion that a warm climate is not liable to be conducive to a higher culture, there is plenty of evidence to the contrary here and elsewhere, and considering the insular position of the Islands, their limited food supply, the lack of raw materials for manufacture, the absence of such metals as iron and copper and the want of domestic animals as beasts of burden, the Hawaiians achieved a remarkably high stage of development before their discovery. The degree of their development is especially shown, as we shall see, by the thoroughness with which they had explored their environment and utilized the natural raw materials which it supplied.

The easy tropical conditions, as well as the unsettled political state which surrounded them originally, were not necessarily conducive to the highest physical or mental achievements. According to Blackman, the regular recurrence of a sufficient amount of food to supply their needs may also have prevented the development of the traits of thrift and frugality that are so inbred in the races of the north. There is no doubt that the bright, warm, cheerful climate had its influence on their temperament, their health, and their home life, by diminishing the relative importance of permanent shelter, by enticing the people out of doors; and also on their morality, as we interpret it, by rendering clothing the thing least required for bodily comfort.

Inter-Island Communication.

Another important point in their environment was the fact that the inhabited islands were sufficiently numerous and near enough together to influence one another decisively, yet far enough apart to make inter-island communication difficult. The group was far enough removed from other groups to prevent frequent migrations and small enough to render a wandering life and contact with other people and tribes impossible. At the same time they were just far enough away from each other to satisfy the natural human desire for travel, adventure and experience.

Inter-Tribal Wars.

The valleys on the various islands constituted natural divisions of the land that had a marked influence on the government of the people by district chiefs who were frequently at war with one another. To offset this there were intertribal and inter-island marriages enough to produce a uniform stock throughout the group. This interchange of blood and ideas was most beneficial in bringing about the homogeneity and compactness necessary to preserve inherited habit and secure the persistence of traditions, customs and the learning of the whole people.

Agriculture and the Food Supply.

Although the valleys are usually fertile, they are limited in extent. The soil though rich, varies greatly in productiveness, and being of a porous nature, needs much water to render it valuable for the various pursuits of agriculture. To meet this demand, extensive irrigation systems were built and used by the native farmers. Besides the valley lands, there are broad tracts of rough lava and dry upland country that were of little use to the aborigines with their primitive methods of agriculture. In brief, the conditions were such as to require much labor and skill to produce sufficient food from the soil to supply their wants. For this reason, among others, their life was not the one of indolence it is sometimes thought to have been, yet conditions were uniformly more favorable to life in Hawaii than were those met within certain other groups in the Pacific to which Polynesians migrated and settled, presumably as they did in these islands.

Fauna and Flora Explored by the Hawaiians

So much must be said of the animals and plants in another connection that, though they form an important feature of environment, it will suffice here to note the salient facts. The flora furnished trees for the construction of their canoes and houses, the implements of their warfare and peaceful pursuits, the raw material for the manufacture of their clothing, nets, calabashes, medicines, and above all, a sufficient amount of wholesome food throughout the year to provide for their sustenance.

The most important animals existing on the islands at the time of their discovery by the whites were the swine and the dogs, both of which were freely used as food. There were domestic fowls of the same species as were common throughout the Polynesian islands. The waters about the group provided a never failing supply of fish food. The insects were all inconspicuous and harmless. The only game birds, as ducks and plovers, were not abundant, while the reptiles were represented by a few species of small, inoffensive lizards that were of little importance.

The Hawaiians were preeminently an agricultural people with a natural love for the soil and its cultivation. They had an appreciation of the beautiful in flower and foliage that has had an abiding influence on their homes and home surroundings. They were also skilled fishermen. The lack of animals, domestic or wild, other than the few species mentioned, prevented them from following the hunting and pastoral life, and as a result they were settled in permanent villages, usually along the coast.

Since there were no noxious insects, poisonous serpents or dangerous birds or beasts of prey, there was no occasion for the alertness and constant fear that so frequently makes life in a tropical country a never-ending strain if not an actual burden.

Food and Its Effect on the People.

While the chiefs and the more prosperous of the people were well supplied with meat, the common people had it only at rare intervals. They were forced to subsist on a diet chiefly vegetable, which was lacking in variety, and, although fat-producing, was also diffuse and bulky. To the character of their food may be attributed the habit of alternately gorging; and fasting, which was so common a trait of the ancient Hawaiians, and which is believed to have resulted in the abnormal development of the abdomen, formally so noticeable among them.

Although taro was the staff of life in Hawaii, sweet potato, or yam, also figured largely in the every day diet of the common people. Though meat was never abundant, as has been stated they were not entirely without animal food. Fish was always available, and certain kinds were often eaten raw. Fowl, pork and dogs were occasionally to be had as a change and were much esteemed as delicacies. The poi-dog, when carefully fed and fattened on poi, was regarded as even more delicious in flavor than pork. Dogs always formed an important dish at the native feasts and on such occasions large numbers of them would be baked in earth ovens.

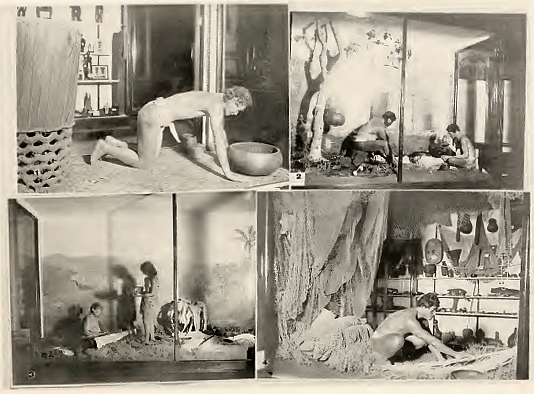

PLATE 4: PREPARING HAWAIIAN FOOD

1. Scraping and preparing a pig (puaa) for baking. 2. The earth oven (imu) hollowed out and filled with heated stones ready for the food. 3. The imu filled and closed; the heat and steam bakes the food which is wrapped in ki or banana leaves. 4. The food baked and ready to be eaten, 5. Pounding poi on a "double" board (papa kui poi), which is a shallow trough made of hard wood; "single" boards were also common. About the grass house may be seen cocoanut palm trees in the rear, papaya trees to the right and left and a small noni tree at the end of the house.

Response of the Natives to their Environment.

Looking broadly at their environment it may be said that the most decisive factors in the surroundings of the Hawaiian race were isolation, the evenness of the climate and the conditions which made the pursuit of agriculture a necessity. The latter induced a more regular and constant activity and more settled life than is found among a hunting and roving people, and in connection with the other conditions mentioned it had an important bearing on the temperament of the race. The isolation, even temperature, and always sufficient food supply must have had their effect in producing a patient, tranquil. self-reliant mind—a satisfied disposition—an even temper—a settled attachment to the soil—an aptitude and faculty for the development of their peculiar forms of learning, and above all, habits of life and customs of dress that were peculiarly suited to and the result of the gentle demands of their environment. Back to Contents

CHAPTER 3: Physical Characteristics of the People; Their Language, Manners and Customs

Stature and Physical Development of the People

At the time of the discovery of the Hawaiians they were physically one of the most striking native races in the world. Moreover, they were distinguished as being among the kindest and most gentle mannered of people, and but for the oppression of their priests and chiefs, they would undoubtedly have been among the happiest.

As a race they were tall, shapely and muscular, with good features and kind eyes. In symmetry of form the women have scarcely been surpassed, if equaled, while the men excelled in muscular strength, particularly in the region of the back and arms.

The average height of an adult Polynesian is given as five feet nine and a third inches, and the Hawaiians were well up to, if not always, that average, while individuals of unusual size, often little short of giants, were not uncommon among them. There is an authentic record of a skeleton found in a burial cave that measured six feet seven and three-quarters inches in length, and there is sufficient evidence to establish the fact that men of even larger stature were by no means unusual. Instances of excessive corpulency have been common among Hawaiians, especially among the chiefs who were always better nourished than were the common people. Having plenty to eat and little to do, they grew large and fat. This tendency to corpulency, as has been elsewhere noted, was, however, more common among the women. Many of them were perfectly enormous in size, but this is not to be wondered at since the Hawaiian ideal of female loveliness includes stoutness of figure as a fundamental requisite.

The natives, before their mixture with foreigners, were a brown race, varying in color from light olive to a rich swarthy brown. Their hair, usually raven black, was straight, wavy or curly, but never kinky. Their lips were of a little more than medium thickness, with the upper lip slightly shortened. This gave to the mouth a peculiar form that is characteristic of the race. Their teeth were sound, regular and very beautiful, a fact frequently ascribed to the character of the food they ate. The nose, a rather prominent feature, was in most cases broad and slightly flattened. The eyes of the pure-blooded Hawaiian were always black and very expressive. Their foreheads were usually high, and perhaps a trifle narrow in proportion. In general, their features were strong, good-humored, and in many instances, when combined with their splendid physiques, produced a striking and impressive personality that gave the impression of their belonging to a very superior race.

Clothing of the People.

At the time of their discovery the men wore the malo, a plain piece of tapa cloth, about the loins in the form of a T bandage. The women wore the pa'u of tapa, which was a simple piece of bark cloth, wrapped about the waist, to form a short skirt, that hung down to the knees. While the foregoing were the usual articles of dress they were by no means averse to answering the call of their environment by stalking about naked or nearly so, if a pretense offered. They were fond of certain kinds of adornment, particularly flowers, using them as garlands about their necks or as wreaths about their heads. The children while often wearing flowers about their necks, went otherwise unadorned until six or eight years of age.

Cleanliness.

Although the Hawaiians wore their tapa cloth clothing as long as it would hold together, the people as a whole took great pride in personal appearance and cleanliness. They were fond of ornaments and were skillful in their manufacture. Both sexes wore ornaments fashioned from shells, nuts and ivory about their heads and shoulders in addition to the flower garlands just mentioned. While tattooing was indulged in as a form of decoration its use in this respect was not carried to the extent that it was among the New Zealanders or the Marquesians. Its principal use in Hawaii was to denote rank or lineage, to brand a slave or sometimes as a token of mourning.

Although the chiefs were markedly superior physically and otherwise, when compared with the common people, they were, nevertheless, descendants of the same race. The difference in stature and capability which they exhibited seems to have been the natural result of their environment. Being better fed, having more leisure, and relieved of the burdens of living and in many ways pampered and protected, they escaped the marks that exposure, excessive toil, hunger, fear and superstition invariably stamp on the less fortunate of every race.

Life in the Open Air

The unusually salubrious Hawaiian climate stimulated the habit of out-of-door life, which was almost universal. The native huts were used chiefly as sleeping places and for protection from the rain. Their aquatic, athletic and sea-going habits were the growth of the open-air life they led. The love of frequent bathing, the nearness of the sea and the necessity of securing at least a part of their sustenance from the ocean, all combined in making them the most powerful and daring swimmers in the world and developed among them, perhaps, the world's most expert and intelligent fishermen.

Their Language and Alphabet

Their language was singularly deficient in generic and abstract terms, but to make up for this general deficiency it was especially rich in specific names of places and things, most of which were derivatives that were full of meaning, frequently taking account of nice distinctions. Broadly speaking the Hawaiian language was little more than a simple tribal dialect of the Polynesian tongue that was spoken with much uniformity in a large number of the Pacific island groups. In fact, there is less variation in meaning and pronunciation of the language throughout Polynesia than exists today between the Spanish and Italian tongues. Besides the language of every-day life there was a style especially appropriate for oratory and another suited to the demands of religion and poetry. Since there was no written language, not even a picture language, at the time of which we write, one of the first acts of the American missionaries was to reduce their speech to writing. For this purpose only five vowels, A, E, I, O, U, and seven consonants, H, K, L, M, N, P, W, were found necessary. In the use of these twelve letters the European pronunciation of the vowels was adopted.

The letter A is sounded as in arm; E as in they; I as in machine, and U as in rule. The diphthong AI, resembles the English ay, and AU has the sound of ow. The consonants were sounded as in English except that K is sometimes exchanged for T, and the sound of L confounded with K and D.

The dearth of consonants

and the over-plus of vowels gave to the spoken language such openness,

fluidity and richness as to be particularly noticeable to persons

unacquainted with the tongue. By some this peculiar quality of the

spoken language, by reason of its intellectual indefiniteness, perhaps,

is believed to represent, or at least reflect, the open, frank character

of the people who developed it.

PLATE 5: HAWAIIAN HOME LIFE

1. The nose flute player and hula dancer. 2. Hawaiian house on a raised stone platform. 3. Making fire by the ancient Hawaiian method: a hard stick of olomea (Perrottetia Sandwicensis) is rubbed in a groove on a soft piece of hau wood until the friction ignites the tinder-like dust that accumulates in the end of the groove. 4. A temporary house made of sugar-cane leaves. In the foreground taro and tobacco are shown, to the left a papaya, while in the background lauhala, banana, breadfruit and cocoanuts may be seen.

Genealogy and History

Their legends and traditions, many of them identical with those found in other groups in Polynesia, as has been stated, were handed down, generation after generation, by a highly honored class of genealogists and bards. Each family or clan had its respected historians and poets, and generally the position of genealogist, at least, became hereditary, to be handed down from father to son. It was the especial office of the genealogist to keep and correctly transmit the historical records of chiefly unions, births, deaths and the achievements of the more important people of their community.

In this way much of the history of the people, as well as many of their legends and much of their historical beliefs, superstitions and practices, have come down to us in fairly accurate form, often from very remote times.

Meles and Hulas

Their meles and hulas were the supreme literary achievements of the ancient historians and poets, and, as their subjects were diverse, they vary much in substance and character. Many are folk songs; some are of a religious order, being prayers or prophecies; others are name songs, composed at the birth of a chief, in his honor, recounting the exploits of his ancestors; the dirge was a favorite form of composition; others again are mere love songs, and still others are composed to or about things and places.

Although they are without rhyme or regular meter, as it is generally understood, many of them are strikingly poetic in spirit. A single example taken almost at random from the many excellent translations given by my friend. Dr. N. B. Emerson, in his book on the Hula, may serve to illustrate their appreciation of the poetic side of nature as well as to demonstrate their natural descriptive power and literary gift.

By way of introduction, we should know that Koolau is a district on the windward, or rainy, side of the Island of Oahu and that the stanza given is one taken from one of the many songs for the hula ala'a papa. It is but an episode from the story of Hiiaka on her journey to Kauai to bring the handsome prince Lohiau to the goddess Pele. Hence,—

Many find a suggestive parallelism of expression in the Hawaiian meles comparable with the Hebrew psalms, others to the rugged poetry of Walt Whitman. No better illustration of this dignified form of Hawaiian poetry can be found, perhaps, than the passage from the dirge, "In the Memory of Keeaumoku," as preserved by the Rev. William Ellis:

As so frequently happens with people gifted with a lyric talent, the Hawaiians were also possessed of an extraordinary musical talent. There were many among them at the time of their discovery that sang with skill, after their own fashion, and they were by no means slow to acquire the technique of our own more intricate written music, a fact which soon revolutionized their form of musical expression.

Marriage

Passing now to the more domestic customs of the people it may be said that among the Hawaiians, marriage was entered into with very little ceremony, except, perhaps, in the case of a few of the more important chiefs. Among all classes the relations among the sexes were very free and it is difficult to determine, with accuracy, what the exact condition was originally with reference to chastity. All the evidence goes to show that the habits of the people in this regard were far better formerly than they afterwards became. Whatever may have been brought about by the coming of white men, and we refer to the hardy seamen of the early days, it is a mistake to assume that wholesale promiscuity existed originally among them comparable to the debasing type found among certain classes in our own scheme of social civilization. Although there was much freedom on the part of both parties in the marriage relation and scarcely any restraint at all among the young previous to entering the more settled domestic arrangement, it is an error to suppose that there was an absence of a definite marital relationship, accompanied by well understood obligations between the parents and their offspring.

Polygamy

By such Hawaiians as could afford and command more than one wife, polygamy was practiced to some extent, rather more as a mark of distinction and affluence than otherwise. The poor and dependent condition of the mass of the common people, if there had been no other reasons, prevented the practice from becoming widespread among them. It is a curious and interesting fact in this connection to note that the Hawaiian called all of his relatives of the same generation as himself "brothers" and "sisters," and those of the next older—"fathers" and "mothers"; those of a younger generation "sons" and "daughters," and so on. This tendency is taken by some as indicative of the uncertain relations that existed among them, since brothers, to a certain extent, shared their wives in common, and sisters their husbands. But the marital form, where one man and one woman habitually cohabit, while yet indulging in other attachments, was the rule among them at all times and in all classes as is clearly shown by the earliest recorded facts on the subject.

It is known that in certain instances betrothals were arranged by parents and friends while the children who were the principals in the arrangement were still quite young. Among the common people, as distinguished from the chiefs, marriage was largely a matter of caprice, but among the chiefs it was a subject of serious concern, involving matters of state, public policy, position and power. Especially was this true at the mating of women of rank, since rank, position and inheritance descended chiefly, though not wholly, through the mother. For example, the offspring of a woman of noble birth would inherit her rank despite the rank of the father. But the children of a father of high rank would fail to retain their position if born to a woman of inferior position.

Marriage Among Persons of Rank

For this reason reigning families were careful to examine into the genealogy of those who were liable to join themselves with members of the more exclusive families. For reasons of policy, brothers were forced on rare occasions to marry sisters, that there might be no question as to the rank of their children.

While there was no set wedding ceremony the event was often made an excuse for a feast; and frequently, particularly among the common people, the bridegroom declared his choice by throwing a piece of tapa cloth over the bride in the presence of her relatives, or less frequently by their friends throwing a piece of tapa over both bride and groom. It is an astonishing fact, that with the exception of marriage, almost every act in the life of the people was celebrated with prayers, sacrifices and religious ceremonies. It cannot be doubted, therefore, that the marriage tie was a loose one, lightly assumed and lightly put off, and depended largely for its duration on the will of the husband. As might be expected, separation was of frequent occurrence among them: and while fond of their children, after time had given opportunity for an attachment to develop between parent and child, it was never-the-less a widespread practice among them, for mothers to part with their babies at birth, giving them freely and without reserve to relatives or friends who might express a wish tor the child.

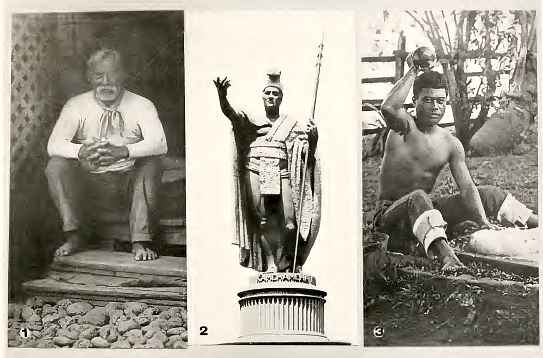

PLATE 6: HAWAIIAN TYPES

1. A sturdy old native in characteristic European dress. 2. The Hawaiian warrior Kamehameha I. From a monument in front of the Judiciary Building in Honolulu, erected, during the reign of King Kalakaua, one hundred years after the discovery of the Hawaiian Islands by Captain Cook. The statue, by an American artist, is a composite based on a painting of Kamehameha by a Russian artist and supplemented by photographs of the finest types of modern Hawaiians. The figure is shown wearing the helmet (mahiole) made of wicker-work covered with feathers; a long cloak (ahuula) of feathers attached to a fine net work of olona; about the chest and over the shoulders is draped the malo of Umi, also made of feathers on an olona foundation. About the loins is tied the common tapa malo—the covering worn by the men of ancient Hawaii when at work; in the left hand is the spear (newa), the chief implement of warfare. The Honolulu statue is a duplicate of the original which was lost in a wreck on the voyage to Honolulu. The sunken statue was subsequently raised and now stands in the court yard at Kohala, Hawaii. Four pictures in bas-relief about the base of the monument (not here shown) represents (a) canoes greeting Captain Cook at Kealakekua Bay; (b) six men hurling spears at Kamehameha; (c) a fleet of war canoes built for the invasion of Kauai, and (d) men and children on the roadside. 3. Muscular young Hawaiian.

Infanticide

There can be no doubt but that infanticide was prevalent among them and that a very large percent of the children born were disposed of in various ways by their parents, soon after their birth. Generally speaking, it appears that in Hawaii, as throughout Polynesia, the struggle for existence and life's necessities, was largely evaded by restricting the natural increase in population in this way. Whatever the cause may have been for this unusual restriction, it is quite generally admitted to have been an effective one so far as keeping the population down to where a comfortable subsistence could be had by all who were permitted by their parents to live past the perilous period of early infancy. From the purely economic point of view this artificial check was most beneficial. Freed from crowding by overpopulation, the primitive community need not live under the scourge of grinding poverty. By limiting the size of the family to the means and ability of the parents to provide, there could be enough for all.

Direct reasoning led them, therefore, to free themselves from the irksome necessity of providing more or dividing less, by restricting the increase in population to a point well within the apparent normal food supply. My friend, Dr. Titus Munson Coan, without upholding the crude methods employed in adjusting the two important factors mentioned, feels the freedom which the people enjoyed from the necessity of providing, to be the main cause of the unusual development of the genial and generous traits of the Hawaiians, and in it finds the principal source of their marital happiness. Other writers account for the practice of infanticide among the Hawaiians on the unpardonable ground of laziness—unwillingness to tike the trouble to rear children. But as we are told that parents were fond of their children and parental discipline was not rigorous, and as children were left largely to their own devices, their care could hardly be regarded as a serious burden; moreover, more girl children were destroyed than boys, indicating that the former reason was the more economic and, therefore, the more human and logical one. On the other hand it may be urged that a certain amount of brutality was always exhibited toward their own kind. The old and physically unfortunate among the common people fared roughly at the hands of the community.

Old age was despised. The insane were often stoned to death and the sick sometimes left to die of neglect or, less frequently, were put to death by their relatives.

Descent of Rank

While the descent of rank through the female line gave women a place of unquestioned importance in their social scheme and often elevated her to the highest positions in the political order, it did not save her from certain forms of social degradation directed irrevocably at all her sex. For example, her sex was excluded from the interior of their chief heiaus. At birth she was more unwelcome than her brother and more liable to be summarily sent to the grave. She was the object of the most oppressive of the regulations of the tabu system. She must not eat with men or even taste food from an oven that had been used in preparing food for them. She was not allowed in the men's eating houses, and several of the choicer food products of the islands were absolutely forbidden her. Such delicacies, for example, as turtle, pork, certain kinds of fish, cocoanuts and bananas, were reserved by the tabu for the exclusive use of the male sex. But as a sort of compensation the men attended to the preparation and cooking of the food, and women were allowed the privilege of accompanying and aiding their husbands and brothers in battle. They could manufacture bark cloth without fear of competition by the men, and they could engage in the practice of medicine, as they understood it, on equal terms with the sterner sex.

The Tabu

Reference has just been made to their tabu system. A cursory examination of it will show what a far-reaching, serious and exceedingly complicated system of penal exactions and regulations it was. No one, not even the king, was altogether free from its influence, and the common people were made to bow to its dictation at every turn of their daily lives. As an institution, the system was both religious and political, in that the violation of the tabu was a sin as well as a crime. As a punishment for its infraction the offender was liable to bring down the wrath of the gods, and they were numerous, as well as bring about his own death, which was often inflicted in an exceedingly cruel and barbarous manner. This extraordinary institution, although common throughout Polynesia, was worked out to a finer detail, and more sternly enforced in Hawaii, perhaps, than in any of the Pacific islands. For the present purpose it would be tedious to sketch the system in anything more than a general way. Suffice to say that the tabu was the supreme law of the land. In its final analysis it was a system of religious prohibition founded on fear and superstition, the interpretation and use of which was in the hands of a powerful and unscrupulous priesthood, the kahunas, who were supported with all the physical power that the kings and influential chiefs could bring to bear.

Some of the tabus were fixed and permanent, being well understood by all the people. Many such there were relating to the seasons, to the gods and to oft-repeated ceremonies. Others were special, temporary and erratic, leaving their inception in the will or caprice of the king or the pleasure of the kahunas. Some of the more burdensome were specific and directed against certain persons or objects. For example, the persons of the chiefs and priests were tabu - as were the temples and the temple idols. Some in effect were exceedingly rigid requirements, others partook more of the force and importance of regulations. There were four principal tabu periods during each month. During these periods a devout chief was expected to spend much time in the heiau. At such times women were forbidden to enter a canoe or have intercourse with the other sex until the tabu was lifted. An especial edict made it incumbent that during the whole period of her pregnancy the expectant mother must live entirely apart from her husband, in accordance with a very ancient tabu. At the periods sacred to the great gods many were put to death for infractions of the tabu, as many restrictions were promulgated and enforced at such seasons, and, through ignorance, the people were liable to disregard them.

We are informed by the people and through the records of early visitors that at such times no person could bathe, or be seen abroad during the day-time, no canoes could be launched, no fires were allowed, not even a pig could grunt, a dog bark or rooster crow for fear the tabu might be broken and fail of its purpose. Should it fail the offenders were made to pay the penalty with their lives.

Any particular place or object might be declared tabu by the proper person by simply affixing to it a stick bearing aloft a bit of tapa, this being a sufficient sign that the locality was to be avoided. The bodies of the dead were especially sacred objects and always tabu. As long as the body remained unburied it was subject to the vagaries of the system. Those who remained in the house or had to do with the corpse were defiled and forbidden to enter other houses in the village.

Owing to the tabu, two ovens must be maintained, one for the husband, the other for the wife: two houses must be built to eat in, a third to sleep in. In a thousand similar ways the system was fastened on every act of the daily life of the people to such an extent that it was ever present, dominating their every thought and deed. It oppressed their lives, curtailed their liberties, and darkened and narrowed their horizon beyond belief. Back to Contents

Complex and bewildering as was the Hawaiian system of tabus, their religious system was even more so. Moreover, the one was so intertwined with the other that the two subjects cannot be treated separated. Since the Hawaiians were naturally a highly religious people, they found many objects to worship and many ways in which to worship them. As a matter of fact, the earth, the sea and the air were filled with their amakuas, in the form of invisible being's, who wrought wonders in the powers and phenomenon of nature. The presence and power of the amakuas was evidenced to them by the thunder, lightning, wind, earthquakes and volcanoes.

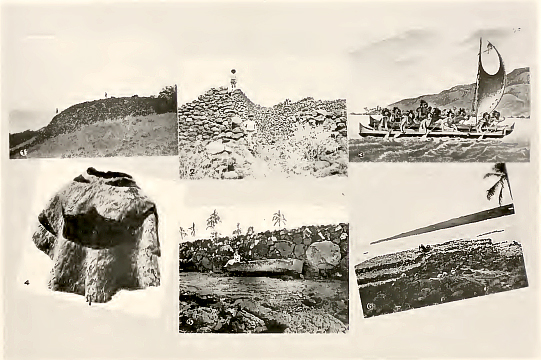

PLATE 7: HEIAUS, WAR CANOES, AND A CITY OF REFUGE

1. The Heiau of Puukihola at Kawaihae—a huge stone enclosure built by Kamehameha I. as a protection against the perils of war. Many human sacrifices were made on this altar to the great war god Kukailimoku; among others the bodies of Kamehameha 's rival, Keoua, and his followers who, on a peace mission, were treacherously slain while landing at Kawaihae from a canoe in the year 1791. 2. Entrance to the Heiau at Kawaiha. 3. Double war canoe equipped with mat sails; the gourd masks worn by the warriors are also shown. 4. Feather cloak (ahuula) worn by chiefs of importance; made of red (iiwi) and yellow (mamo and o-o) bird feathers. 5. The city of refuge, Puuhonuaa, at Honaunau; a stone wall twelve feet high and fifteen feet thick encloses seven acres of tabu ground. To such sanctuaries women and children, warriors worsted in battle, criminals and others in peril might flee for safety from their avengers. 6. Heiau of the open truncated pyramidal type; compare with the rectangular walled type shown in figs. 1 and 2.

Religion Among the Hawaiians

Of the innumerable gods in the pantheon, Ku, Kane, Lono and Kanaloa were supreme. These important gods were supposed to exist in the heavens, in invisible form, and to have been present at the beginning. They were also believed to appear on the earth in human form. In addition to these each person had his or her own titulary deity, and each occupation was presided over by a special amakua, to which worship was due. Thus the fisherman, the canoe maker, the hula dancer, the tapa maker, the bird catcher, even the thieves and the gamblers, all had presiding deities with power to prosper them in their callings and bring them good luck in their undertakings. Other deities were clothed in life in the form of numerous animals and plants. Disease and death were quite naturally regarded as the work of the gods and appreciated by the people as material evidence of their invisible powers.

Idol Worship

They worshipped their deities chiefly through idols made of wood or stone. They believed that such images represented, or in some way were occupied by the spirit of the deity that they sought to worship. The people as a whole had a rather well defined conception in regard to existence after death. They believed that each person had an invisible double. They also thought that after death the spirit lingered about in dark places in the vicinity of the body and was able to struggle in hand to hand encounters with its enemies. A nightmare was interpreted as a temporary quitting of the body by the spirit and in certain cases, through proper prayers and ceremonies, it was believed to be possible to put the soul back into the body after it had left it. This was usually accomplished by lifting the toe-nail of the unfortunate person concerned. Many places were believed to be haunted and the spirit was supposed to journey from the grave to its former abode along the path that the corpse was carried for burial.

The Future State

They had a rather indefinite notion as to the exact nature of the future state. However, they believed that the two usual conditions, misery and happiness, existed. If the soul after journeying- to the region of Wakea was not favorably received, it was forced through despair and loneliness to leap into the abode of misery, far below. Precipices from which the souls of the unhappy departed were supposed to plunge on this wild leap are occasionally pointed out at various places about the group. One at the northern point of Oahu, another at the northern extremity- of Hawaii, and a third on the western end of Maui are well known to those acquainted with Hawaiian superstition.

Heiaus

In order to propitiate their gods, or better accomplish their worship, the people through fear or at the command of the king or priests, erected numerous temples or heiaus. To many students of the race this blind fear of their gods and their chiefs, and their unreasoning acceptance of the tabu, are subjects of continual wonder. Their principal temples were of two general forms, the older being composed of rough stones laid up without mortar in the form of a low, truncated pyramid, oblong in shape, on top of which were placed the altar of sacrifice, certain grass houses, the idols of the temple and the other grotesque wooden images and objects used in their worship. The later and more common form of heiau was made by erecting four high walls of stone, surmounted with numerous images, enclosing a space occupied, as before, by the various images, oracles, sacred places and altars of worship. These temples were numerous in the more thickly settled regions on all the islands and were usually built near the shore. On Hawaii, in the region from Kailua to Kealakekua, particularly, they were very numerous and close together. The principal heiaus were dedicated to their chief gods, but many smaller ones were built, as fish heiaus, rain heiaus and the like, and were dedicated to the special god of the builder.

Where temples were found in large numbers a corresponding number of priests were to be expected. Of these there were many orders and sub-orders. They and their rights were constantly made use of by the chiefs for the purpose of terrifying the people. Through them the tabu was coupled with idol worship, and their combined cruelties, terrors and restrictions made an integral part of the general system of government.

Warfare

War among the ancient Hawaiians was one of the chief occupations and with them, as with other races, war was the "sport of kings." In making preparations for war the king, however, in addition to the council of his chiefs, had the advantage of the advice and skill of a certain class of military experts who were instructed in the traditions and wisdom of their predecessors. Being well acquainted with the methods of warfare that had been successfully resorted to by kings in former times, they were at all times among the king's most respected advisors.

Fortifications, as we understand them, were not a part of their scheme of warfare, though sites for camps and defenses were selected that possessed natural advantages in the matter of their defense against the enemy. That part of the population not actually engaged in battle was sent to strongholds, usually steep eminences or mountain retreats. In case of a rout the whole army retired to these strongholds and valiantly defended them. In addition to these natural forts, there were temples of refuge or sanctuaries to which those broken in battle, or in peril of their lives in time of peace, might flee and escape the wrath of all powers without. These temples were crude though permanent enclosures, whose gates were wide open to all comers at all times.

The Hawaiian warriors had many methods of attack and defense, depending usually on such matters as the strength of the enemy, the character of the battlefield and the plan of campaign. Their battles were generally a succession of skirmishes, the whole army seldom engaging in a scrimmage. They usually, though not always, made their attack in the daytime, generally giving battle in open fields, without the use of much real military strategy. Occasionally interisland wars occurred in the form of naval battles in which several hundred canoes were used by both sides, but as a general thing their differences were settled on land.

Practically the entire adult population was subject to a call to engage in hostilities. Only those who were incapacitated through age or from infirmity were exempt from the summons of the recruiting officer sent out by the king to gather warriors, when anything like an extensive military operation was determined upon. If occasion required, a second officer was sent to forcibly bring to camp those who refused to answer the call of the first. As a humiliation and mark of their insubordination it was a custom to slit the ears of the offenders and drive them to camp with ropes around their bodies.

Preliminary to a Battle

The army stores were usually prepared beforehand, and each warrior was expected to bring his own provisions and arms. Not infrequently notice of an impending attack was sent to the opposing forces and a battlefield mutually satisfactory to both forces selected for the engagement. The women took an active share in the important part of the work connected with the commissary; often following their husbands and brothers onto the battlefield, carrying extra weapons or calabashes of food. When the forces were assembled and all things in readiness for the fray, an astrologer was consulted by the king. If the signs were auspicious the battle would be undertaken. As the opposing armies approached each other, the king's chief priests were summoned to make the king's sacrifice to his gods. Two fires being built between the armies, the priests of each army made an offering, usually a pig which was killed by strangling. When the various religious ceremonies were over the battle would begin, the, priests accompanying the armies, bearing their idols aloft that the bodies of the first slain in battle might be properly offered to the gods. Their idols took the place of banners. During the heat of battle they would be advanced in the midst of the warriors, while the priests, supporting them, to cheer their followers and spread terror in the hearts of the enemy, would give blood curdling yells accompanying them with frightful grimaces, all of which were supposed to come from the images themselves, and to be an unmistakable token that the gods were in their midst.

In opening the attack, it is related, a single warrior would sometimes advance from the ranks, armed only with a fan and when within hailing distance would proceed to blackguard the enemy, daring them to attack him single-handed. This exasperating challenge would be answered by a number of spears being hurled at the taunting warrior, who would nimbly avoid them or seize them in his hands and hurl them back at the enemy. Such incendiary maneuvers were well calculated to precipitate trouble and not infrequently they resulted in the death of the intrepid warrior. A fierce struggle would then follow to gain possession of his body.

Their battles were often almost hand to hand encounters, lasting sometimes for days. However, they do not seem to have been very fatal. Often they resulted in routing one party or the other, the conquerors taking possession of the land and portioning it out among the victorious chiefs. A heap of stones was made over the bodies of the victorious dead, while the vanquished slain were left unburied. Captured warriors were occasionally allowed their freedom, but more frequently they were put to death or kept as future sacrifices. The women and children of the captured were made slaves and bound to the soil.

When peace was sought a branch of ki leaves or a young banana plant was borne aloft by the ambassadors as a flag of truce. When terms were arrived at a pig was sacrificed and its blood poured on the ground as an emblem of the fate of the party to the treaty who should break its conditions. The leaders of both armies would then braid a lei of maile and deposit it in a temple as a peace offering. The heralds were then sent running in all directions to announce the termination of the war, and the event would be appropriately celebrated with feasts, dancing and games.

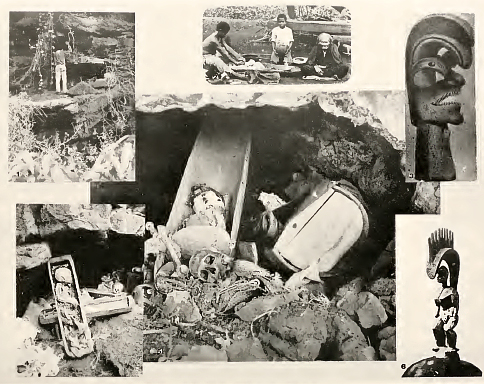

PLATE 8: BURIAL CAVES, WAR GODS AND IDOLS

1. Typical Hawaiian burial cave. The common people after death were usually secreted in caves in the neighborhood; the burial took place during the night. Great care was taken, however, to hide the bones in secret places to prevent them from being used for fish hooks and arrow points. The important bones of the kings, including the skull, leg and arm bones, were gathered from the decayed flesh, collected into a bundle, wrapped with tapa and bound up with cord; the bundle was then deified by elaborate ceremonies before the bones were placed in the most secret and inaccessible caves, often being carried from one island to another. The bones of a high chief were preserved in vault-like caves in the cliffs and not infrequently were laid at rest in the warrior's canoe together with other precious possessions belonging to the departed. 2. An aged kahuna. 3. Kukailimoku, the god of war; taken from a figure in Cook 's Voyages; other representations of this god are on exhibition in the Bishop Museum. 4. Burial cave (near view of fig. 1) showing a ''transition" burial in a coffin hewn from a log. 5. Burial cave showing portion of a canoe, mats, tapa, etc. 6. Ancient wooden idol. Prior to the landing of the missionaries idolatry was abolished and the idols of the nation hidden away in caves; later many of them were collected and burned. A number, however, were preserved and are now in museums in Hawaii, America and Europe.

The King and His Power.

The king was the recognized head of all civil and military, also ecclesiastical authority. The lands, the people, their time, their possessions, the temples, the priests, the idols, the tabus, the prophets, all belonged finally to him. Everything was his to use as he willed so long as he was in the favor of the gods. The priests, who were the only ones skilled in interpreting the oracles and learning the wishes of the gods, were also the class which determined the offerings that would placate the deities worshipped. In this way, through fear, they were able to hold no small amount of influence over the affairs of state by reason of the king's dread of the wrath of the gods of his realm.

The high priest kept the national war god and was at all times in close relation to the monarch. Other priests were charged with perpetuating the traditions of the people as well as their own medical, astronomical and general learning. Besides the regular orders of priests there was a numerous class of more irregular priests or kahunas, that were little more than sorcerers. They were able to cause the death of persons obnoxious to themselves, their clients, their chiefs or their king.

In order to pray any person to death it was only necessary for one of their kahunas to secure the spittle, the hair, a finger nail, or personal effects belonging to the intended victim, and, by means of certain rites, conjurings and prayers to the gods, to so work upon the fear and imagination of the individual as to almost invariably cause his death. As a result they were unpopular as a class and not infrequently were conspired against by the people, or themselves prayed to death by the more powerful of their cult.

The Nobility, Chiefs and Common People

In the time of which we write the population was divided into three classes, the nobility, including the kings and chiefs; the priests, including the priests, sorcerers and doctors; and the common people, made up of agriculturists, artisans and slaves taken in war. There was an impassable gulf between the classes including the chiefs and the common people.

The distinction was as wide as though the chiefs came from another race or a superior stock, yet as we have said elsewhere they were undoubtedly all of one and the same origin with the people under them. A common man could never be elevated to the rank of a chief, nor could a chief be degraded to that of a commoner. Hence the rank was hereditary in dignity at least, though not necessarily so as regards function, position or office. Within the class of the nobility, sharp distinctions were numerous and a certain seniority in dignity was maintained. As far as can be learned there was no distinction between civil, military, ecclesiastical and social headship, and there was no separation between the executive, judicial and legislative functions. The power, in an irresponsible way, was entirely centered in \ho hands of the nobility.

Since the chiefs were believed by the common people to be descended from the the gods in some mysterious and complicated way, they were supposed to be in close touch with the invisible powers. They were looked up to with superstitious awe, as being both powerful and sacred. This advantage was shrewdly employed by the ruling class in securing the respect and unquestioned submission of the common people. Death was the penalty inflicted for the slightest breach of etiquette. Through the enforcement of such submission the chiefs were able to exact the marks of distinction claimed by them from the masses, and to control and direct them through a blind rule of duty. Singularly enough the chiefs were respected while living and in most cases were revered by the people after their death.

Among the chiefs themselves there was constant bickering and class rivalry. The moi, or king of each island usually inherited his position, but the accident of birth did not guarantee that he would long remain in power, for unfortunately the assurance of his pace lay in the hands of the district chiefs under him. Seldom could they' be relied upon for unshaken fealty. Their love of power and capacity for intrigue, as a rule, was not of a common order and they were often able to demonstrate their complete mastery of the game of politics.

The important chiefs were therefore usually summoned by the king to sit in council as an advisory body when weighty matters were to be passed upon. But the immediate source of all constructive law as such, among the ancient Hawaiians, was the will of their king. Not unlike kings in more enlightened lands, they were guided in important matters by their stronger chiefs whose influence they required. These, in turn, were influenced by and dependent upon the good will of the people under them, for there was nothing to prevent the common people from transferring their personal affections and allegiance to other and more considerate chiefs. But back of the king, the chiefs, and the people was the traditional code of customary law that served as a powerful restraint on the king in preventing the promulgation of purely arbitrary decrees. The traditional law of the land related mostly to religious and customary observances, marriage, the family relation, lands, irrigation, personal property and barter. With such crimes as theft, personal revenge was the court of first resort. The aggrieved person had the right, if he so desired, to seek the aid of a kindred chief, or to resort to sorcery with the aid of his kahuna. The king, however, was the chief magistrate, with his various chiefs exercising inferior jurisdiction in their own territories.

The King and the Land

The king was regarded as the sole proprietor of the land: of the people who cultivated it, the fish of the sea,—in fact everything of the land or in the sea about it was the property of the king. The king, in short, owned everything, the people owned nothing, so that technically, the people existed in a state of abject dependence. The system that developed from this was one of complete and absolute feudalism. The king made his head chiefs his principal beneficiaries. They, in turn, established a grade of lesser chiefs or landlords, who gathered under them the common people as tenants at will. The lands being divided, those who held the land owed every service and obedience to the chieftain landlords. On these landlords the king relied for men labor munitions and materials to carry out his plans and fight his battles.

Taxes

This system was so offensive that it is said that the laborer did not receive one-third the returns due him for his toil; the lion's share of everything, even in this simple system, went to the over-lords, in the form of a tax. There was first, the royal tax that was collected by each grade paying to its superiors until the whole tax, which consisted of such articles as hogs, dogs, fish, fowl, potatoes, yams, taro, olona, feathers, and such articles of manufacture as calabashes, nets, mats, tapas and canoes, was collected. In addition to the foregoing, the people were subject to special taxes at any time, and labor taxes at all times, when they were called upon to build walls, repair fish ponds, cultivate the chief's taro ponds, or construct or repair the temples.

Besides all these, and other means of taxing the people, there were customs which made it necessary to make extraordinary presents to the king, especially when that dignitary was traveling, with the penalty that if enough presents were not brought, plunder and rapine was the consequence. With this hasty review of some of the more general and especially interesting or striking peculiarities of the Hawaiian people, as a branch of the Polynesian race, that are of importance as salient characteristics when we wish to compare them and their natural human history with that of other races of mankind, we can now pass to a brief review of their arts, occupations, ornaments, weapons, tools and kindred subjects in which they made use of the materials with which nature surrounded them. Back to Contents

CHAPTER 5: The Hawaiian House: Its Furnishings and Household Utensils

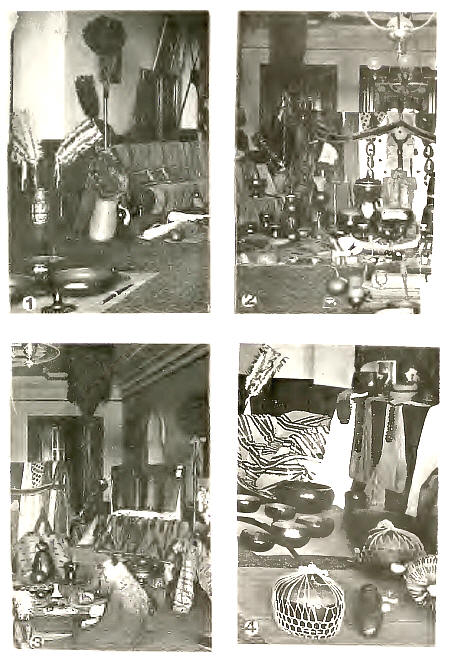

The houses of the common people were little more than single-room straw-thatched hovels, supported upon a crude frame-work of poles, the structure in many instances being scarcely sufficient to shelter the family. On the other hand, the houses of the better class, notably the chiefs and the nobility, were much superior. Being well built and neatly kept, they were not so devoid of simple comfort as their absolute lack of architectural beauty might suggest.

While their houses varied much in size and shape they were uniformly dark and poorly ventilated, being invariably without windows or doors, save the small hole left, usually on one side, through which the occupant might pass in and out in a crouching posture.

Complete Domestic Establishment

As with the various occupations that had to do with the gathering of their food and the making of their raiment, so the building of the house which sheltered them was attended by many important religious observances, the omission of any of which might result in the most serious consequences. Every stage, from the gathering of the timbers and grass in the mountains, to the last act of trimming the grass from over and around the door before it was ready for final occupancy, furnished an occasion for the intervention of the priests and the imposition of special tabus that must be satisfied before the house could be used as a dwelling.

As has been suggested elsewhere, a complete domestic establishment was made up of several conveniently grouped single-room houses that were given over to special purposes. The well-to-do Hawaiian boasted of at least six such single-room houses. The house for the family idols and the men's eating house were both always tabu to women. The women's eating house, a common sleeping house, a house for the beating of the tapa, and lastly, a separate house for the use of the women during various tabu periods made up the group. Occasionally the better houses were on a raised stone foundation, and a fence made about the group to separate them from their neighbors and to mark the limits of the sphere of domestic influence. To the foregoing might be added a house for canoes, a storehouse, and others for special purposes as might be required.

Building of a House

The building of a grass house of the better type was an important task and one that called for much skill and experience. The timbers of which it was constructed were selected with great care, different woods being preferably used for certain purposes. When trimmed of the outer bark, notched and fashioned into shape by crude stone tools they were placed into the positions which they were intended to occupy in the framework of the structure and then firmly bound together with braided ropes of ukiuki grass.