Old Time Hawaiians and their Work

|

COPYRIGHT, 1912, BY MARY S. LAWRENCE DEDICATED TO THE BOYS AND GIRLS OF THE HAWAIIAN RACE This book was written primarily to supply the children of Hawaii with a history of their own race. It ought to be of interest also to children in America, who know so much about their Indian neighbors, but have only a vague conception of the Hawaiian, whose interests are so closely linked with their own. The First People And How They Came

Umi, The

Mountain King Powerful Enemies Of Kamehameha I Kahekili, the "Thunder of Maui" Powerful Friends Of Kamehameha I Kalanimoku, Called The "Iron Cable Of Hawaii" Kamehameha II, Who Overthrew Idolatry Noble Women Who Aided The Spread Of Christianity Keopuolani, the "Gathering Of The Clouds Of Heaven" Kaahumanu, the "Feather Mantle" Kapiolani, the "Arch Of Heaven" Kamehameha III, Who Gave The People The First Written Constitution Bernice Pauahi Bishop, The Princess Who Might Have Been Queen The Hawaiian Islands occupy a central position in the North Pacific Ocean and lie just within the tropics. They are about 2,100 miles from San Francisco and 4,703 miles from Manila. The islands form a chain rather than a group, and extend from northwest to southeast for a distance of 380 miles. The eight inhabited ones have a combined area of 6,454 square miles. In the order of size they are Hawaii, Maui, Oahu, Kauai, Molokai, Lanai, Niihau, and Kahoolawe. Honolulu, the capital, is on the island of Oahu, and has a population of about 45,000. The first inhabitants migrated from Polynesia about the sixth century after Christ. After the thirteenth century the voyages ceased, and the islands were cut off from communication with other countries until 1555, in which year they were discovered by the Spanish, who kept the discovery a secret. In 1778, the English rediscovered them and made them known to the rest of the world. At that time Kamehameha I was a young chief. In 1795, he united all the windward islands (Oahu, Molokai, Maui, Lanai, Kahoolawe, and Hawaii) under one rule, and, in 1810, Kauai was ceded to him. He gave the people a firm government and did away with the wars of petty chiefs. He recognized the superiority of foreigners, and courted their friendship to further his aims and to advance his country. A new epoch begins during the reign of his son Liholiho, who became Kamehameha II (1819-1824). In 1819 idolatry was overthrown, and the following year saw the introduction of Christianity. Its influence was felt during the reign of Liholiho's brother Kauikeaouli, who ruled as Kamehameha III (1825-1854). The missionaries reduced the language to writing, and used their influence toward good laws and a written constitution. The next two rulers, Kamehameha IV (1855-1863) and Kamehameha V (1863-1872), were sons of the queen regent Kinau, and grandsons of Kamehameha I. The former, with his wife, Queen Emma, will be gratefully remembered for founding Queen's Hospital in Honolulu. Kamehameha V disapproved of some of the reforms of Kamehameha III. During his reign a new constitution was framed requiring educational and property qualifications for voters. William C. Lunalilo, a grandnephew of Kamehameha I, became the next ruler (1873-1874). In his will he provided for the Lunalilo Home for Aged and Poor Hawaiians. As he was the last of the Kamehamehas, the legislature chose his successor from the descendants of two of the Kona chiefs. David Kalakaua (1874-1891) made a journey around the world to gain knowledge concerning the immigration of laborers for the plantations. This was because of the reciprocity treaty of 1876, which gave an impetus to the sugar industry. The treaty gave Pearl Harbor into the control of the United States, and the latter admitted Hawaiian sugar free from duty. Kalakaua was succeeded by his sister Liliuokalani (1891-1893). She attempted to change the constitution so as to restore the old powers of royalty. The revolution which followed resulted in the overthrow of the monarchy and the establishment of a republic with Sanford B. Dole as president. On August 12, 1898, the islands were annexed to the United States, and in 1900 they were organized as a territory. Their central position has made them of importance from both a military and a commercial standpoint. As a possession of the United States they have become widely known for the beauty and grandeur of their scenery, and each year brings" an increasing number of Americans to their shores. An interest in the Hawaiian of to-day naturally leads to an interest in his ancestors and in the part which they played in the making of Hawaii.

About seven hundred years ago a crowd of people were gathered on the shore of one of the islands of Hawaii. They were dark-skinned, with coal-black hair, and wore little clothing in that mild climate. The men had malos l about their loins, and the short tapa skirts of the women came just below their knees. They were talking loudly and pointing out to sea, where a large double canoe could be seen through the morning mist. They could hear the command "Hoe, hoe!" and could see the flash of many paddles. Then the strange sea bird was carried ashore on a huge breaker, amid the shouts of the people. Manuia, the fisherman, forgot everything in his excitement. He watched the chief and his family alight. The chief's wife carried a bundle wrapped in tapa, which she held carefully, although she looked exhausted. Keha, the village chief, received them kindly and took them into his royal palace. Manuia then turned to watch the pilot and the hardy paddlers. He admired their skill and daring, and crept as near as possible to hear their stories. He knew that they had come from the far-away Kahiki, where he had longed to go. As they ate and drank they recounted their experiences. "We have been many moons on the water," said one, between huge mouthfuls of the refreshing poi. “The fierce wind gods tried to wreck us. Our priest offered many prayers to Kane-huli-koa, and we made offerings to him. Then he brought mild winds and sent many fish near for us to spear. At the end the voyage it was hard, for our food was scarce and the nights were cold. Our chief is a brave alii to bring us here safely. His singer is even now composing a mele in memory of the voyage." As darkness descended Manuia remembered his home. As he neared his canoe he heard a child's cries, and to his astonishment found a wee baby rolled up in tapa in the bow of the boat. He did not connect the baby with the bundle which he had seen in the queen's arms. He did not even wonder where it came from, for his faith in the gods was so great that he accepted it at once as a present from them, and hurried home to tell his family of his strange adventure. There was much excitement over the new baby, and all the neighbors rushed in to get a look at it. They chattered away in a noisy chorus, but all seemed to agree that it was a gift of the gods. It was a common thing for people to adopt children, and Lehua, the wife, took her new charge as a matter of course. As she unrolled the tapa she said : "The baby must have come from Kahiki. See, the tapa is a different pattern from ours! It is not so fine in quality as some that I have made." The baby was called Keikiwai, which means "water child," and was brought up with the other children, unconscious of his foreign birth. Manuia's children lived in the water most of the time. Keikiwai learned to swim as soon as he could walk. It was not long before he could catch the little fishes, which he ate raw. He could dive and float and swim with his feet interlocked. Sometimes he stayed under water so long that his sister Leilehua was alarmed. He was fearless, and always did what his older brother, Kaipo, dared him to do. On land he often ran races with Kaipo. Although the latter was taller, Keikiwai made his little legs go so fast that he usually won. One day the children were surf riding. " See the little keiki, " exclaimed Lehua, who was taking a sun bath with Manuia after a vigorous swim. Manuia looked. There was Keikiwai standing on his surf board, balancing himself fearlessly as he rode in on a huge breaker. Then he changed his position and stood on his head. " Why, that is better than I can do," said the proud father, excitedly. "But wait! he will have a tumble before he reaches shore." On came the child. Every one stopped to watch him, for it took much skill to keep his position. As he neared the shore he gave his board a mighty push which sent it upon dry land, and then dived into the water and disappeared from sight. The people cheered, for few experienced men could have done better in so rough a sea. " He is surely a child of the sea god," said Manuia;" I will take him to fish with Kaipo and me." After that, while Leilehua was helping her mother make tapa or weave mats, Keikiwai went with his father and brother to catch fish. Manuia could do many things, and he taught his boys how to make weapons and tools, to cultivate taro, to build canoes. But he loved the sea best, and had become famous as a daring fisherman. So of course he wanted his sons to know all about the sea. Kaipo was content to fish from the canoe with a net or with a hook and line, but Keikiwai liked best to dive into the water and spear the fish. One day Manuia and Kaipo were busy with the fish net and did not notice the approach of a large man-eating shark. Keikiwai saw the striped pilot fish first and seized a spear. Then he quietly slid into the water and lay still. It was not long before the huge shark discovered him. The boy remained motionless until the big jaws opened wide; then with a quick movement, he thrust the spear into the dangerous throat, pushing it with all his strength. Manuia turned just in time to see that the shark was dead. There was no prouder boy in the village that day than Keikiwai. His mother rewarded him with a large calabash of poi, some dried shrimps, and some baked sweet potatoes. Leilehua rubbed noses with him and wept for joy. She made lets of the lehua blossom, which she put around his neck. Even the pig seemed to know that he was the favored one, and came up to be petted by him. For many days after that Keikiwai was busy making a lei of the shark's teeth. He had to bore a hole through each tooth, and this took much patience. Then he made fishhooks from the bones. These trophies were incentives to do more brave deeds. One day Keikiwai and Kaipo took presents of fish and tapa to the great chief, Keha. On their way home they passed a fishpond. "Always tabu," said Keikiwai discontentedly, pointing to the white tapa waving in the breeze, which meant that no one should dare to catch any fish. " Keha has too many fish. I defy the tabu." Thereupon he snatched an ama-ama, or mullet, and crammed it down his throat. " Flee to the mountains! " cried Kaipo, very excitedly. “The priest was looking. Run!" Keikiwai needed no second warning. He saw the priest and knew that, if caught, he would be offered in sacrifice to the great god Ku. Already men had started in pursuit of him. Dogs barked, people shouted, and a crowd collected. It was an exciting race. To Kaipo's great relief Keikiwai gradually gained on his pursuers, and he was far ahead of them when, at the foot of the mountain, he disappeared in the dense foliage. With gigantic leaps he bounded forward. It was hard to make headway through the tall ferns and shrubs which grew thickly between the trees. The shouts of his pursuers goaded him onward and upward. Sometimes the loose rocks gave no foothold, and he slipped back. Often he saved himself by clinging to some tough vine. His climb led him across the winding trail. Once he almost ran into a party of men who were on their way to the adz factory, up near the top of the mountain. Keikiwai's sudden appearance startled them as he leaped into the thicket. To the left of him he heard men felling the tall forest trees. He could hear the thud of their adzes, also their laughs and shouts. He knew that they were getting material for a grass house which Keha had ordered for himself. Keikiwai turned to the right so as to avoid them. Higher and higher he climbed. The mountain became steeper, and his bare skin was bruised and scratched, but he dared not stop. At last he reached an open space separated from his pursuers by a high precipice. Here, at last, he felt secure. He drank greedily from a mountain stream which tumbled noisily over the rocks. After satisfying his hunger with ohelo berries and mountain apples, he fell into a deep slumber.

After his meal he made a cape of ti leaves, for his malo was not much protection from the cold wind. He did not pick the lehua blossoms for because he knew that if he did, it would be sure to rain, and he feared a BANANA TREE drenching. The sun set suddenly and there was no twilight, so Keikiwai hastily rebuilt his fire and made himself a bed of soft grass. He did not feel sorry that he had offended the gods, but he feared punishment. He believed that the god who made his home near by would hurl stones uponhis head. So he built an altar of stones and offered as sacrifice some ohelo berries which he had picked. Then he muttered a prayer and fell asleep. Keikiwai awoke with a start. The great god had come to him in a dream and had threatened him. He glanced at the altar, and there was the food untouched. " Ku is angry," he muttered, as he shook with fear; "I may not like the tabus, but if the great gods make them, I must obey them. I will give myself in sacrifice." He stood up where he could see his surroundings and look for his pursuers. As he watched the sun break its way through the clouds behind the mountains, the grandeur of the scene seemed to soothe him. " Ku will not kill me, but will help me to flee to the puuhonua, where no one can harm me." Then, raising his voice, he called, " Help! " and the echoing " Help " was a direct answer which gave him courage. Keikiwai knew that dangers lay ahead of him, for his pursuers would not give up the search. They would guard the paths to the puuhonua, for there, if he reached it, they dared not touch him. He had to climb down a steep cliff, and pass a village where he might be recognized. He made a long swing of the tough convolvulus vine and tied one end securely. Down, down he let himself until he was on a level with a jutting rock about ten feet from him. To swing himself and then leap to the rock was the work of a moment. His quick ear caught the sound of falling water, and he scrambled to the edge of the falls. Twenty feet or more below him was a pool of deep water. The dive from above was mere play for him, and the cool water was refreshing. Shaking himself like a wet dog, he hurried on. Sometimes he pushed through the dense foliage ; more often he leaped from stone to stone in the stream. The sound of drums encouraged him, for if the people of the village were merrymaking, there was a chance of his passing by unnoticed. He crawled behind the bushes and peered through. He saw the people on the beach watching four girls dancing the hula. Their slow, rhythmic movements were so graceful that he forgot his danger in the enjoyment of the moment. Then the dance became livelier, the drums beat faster and louder, and Keikiwai took this chance to pass by, unseen. In his haste he stumbled over a sleeping pig, whose squeals attracted the people standing near by. Unfortunately, his pursuers were among them. They had forgotten their mission when the drums began to beat, but the sight of Keikiwai aroused them to action, and they rushed after him. Keikiwai breathed a silent prayer to Ku, and it gave him courage, but the others were starting out fresh, while he had already gone a long way. Once he glanced back and saw that they were gradually gaining on him. Ahead of him could be seen the welcome walls of the puuhonua. He dared not turn his head again, but the shouts told him that he was still several yards ahead. On and on he flew, and on and on flew his pursuers. He had nearly reached the open gate when he tripped upon a stone and down he went. The foremost man was almost upon him. He never could have told afterwards whether he rolled or crawled or slid into safety, but he knew that the priest drove the others back ; then he lost consciousness. He was kept in the house of refuge for several days. After being purified by prayer and sacrifice he was allowed to go home unharmed. You would suppose that his family would have been mourning for him while he was in danger, but people in those days did not think much about each other, nor did they worry, but lived from day to day. When he returned, however, they greeted him with tears of joy, for they loved him as much as they were capable of loving. Several weeks later Keikiwai could be seen on the lanai mending his papa holua. He heard the herald blowing his conch shell and stopped work to hear the message. He knew that the chief, Keha, had something of importance to tell the people. This is what he heard: "To-morrow the alii Kaolani visits Keha. Games will be played in his honor, and many presents of food are expected from the people." Keikiwai wanted to join the holua race. "It is only for those of noble birth," said the messenger, and passed on to spread the news. Lehua had been watching her son and noticed his disappointed face. She had observed of late how manly he was growing and with what dignity he carried himself. He had always been a leader among his playmates. Moreover, his life had been spared when he broke the tabu. These facts seemed to prove that he was no ordinary child. Lehua was not troubled; she knew that Kaolani was the chief who had arrived the night that her baby came. He had not gone back to Kahiki, but had settled on the next island. Now was the time to act. She crawled through the low doorway and groped about until she found an old calabash which had not been touched for years. She brought it out and opened it before Keikiwai. It contained a piece of tapa. " This is yours," she said, and she told him how Manuia had found him. The next day Keikiwai was late for the races, so when he arrived in his plain malo no one noticed the papa kolua in his hand. Everybody was watching the royal party, who sat on mats under the spreading branches of a hau tree. Keha wore a red-feather helmet, a gift from his guest. His long red-feather cape with yellow border was thrown back, showing his palaoa and his red malo. His beautiful wife sat next to him. Her red and yellow pau was of the choicest tapa. Yellow feather lets, interwoven with maile, crowned her long black hair, and around her neck were lets of the fresh ilima. The guests had seats near by. They were also gorgeously dressed. Retainers stood near, who saw that they had every comfort. Keha acted as judge. Each chief who was to race carried his own papa Iwlua and in turn stepped before the judge and recited his genealogy. This was to make sure that all were of noble rank. The last chief had finished and started up the hill when Keikiwai came forward. The people showed much concern, for they all recognized him as a common fisherman. Would Keha have him killed for attempting to race with chiefs? Handing the tapa to Keha, he told his story and asked if he might join the race. Keha passed the tapa over to Kaolani and his wife Kalei. Tears of joy sprang to the eyes of Kalei. " This is the tapa which I made for my little water baby before we left Kahiki, and when he was born at sea I wrapped him in it This must be our child whom we thought the cruel shark god, Moku-halii, had devoured. Go into the race, my son, and show yourself worthy of your ancestors." Drums beat loudly as Keikiwai bounded up the hill. Many of the chiefs recognized him, and did not like the idea of racing with him. "Ho, ho, my akakane" said the nearest one scornfully,” you had better slide on a surf board and get your nurse to race with you." There was no time for Keikiwai to answer. The signal was given and on they ran. It was a pretty sight to see each one jump upon his narrow sled at the brow of the hill. Down they came, and the spectators held their breath with excitement It took much skill to keep balanced, and several upset and rolled over and over in the slippery grass. Keikiwai forgot the crowds. He strained every nerve to keep his balance. Once he almost lost it, but saved himself by steering differently. Then on he went faster than before. Slowly he gained upon some of the chiefs who had been ahead, for in the long run his skill counted for more than their experience. One by one he outdistanced them, and at the end he came in just a little ahead of the foremost one. It was an exciting race, for no one knew until the end how it was going to turn out. Keikiwai heard the loud cheering, but he was too exhausted to care. Retainers carried him to the royal lanai, where they lomi-lomied him and rubbed him with coconut oil. He lay there dazed but happy, for it was a new and delightful experience to be cared for in this fashion. They dressed him in a red malo and put a palaoa around his neck. After the games came the luau or feast. Great preparations had been made for this important occasion. The royal guests sat on the ground around a table of fern leaves, and Keikiwai was placed at one end next to his new-found father. He saw the women eating in another place, but this did not seem strange to him ; with all classes of people it was tabu for men and women to eat together, and ever since he was four years old he had taken all his meals with men only. But it did seem queer to be eating with chiefs, for he was accustomed to approach them on his hands and knees. He watched his father closely, otherwise he would have drunk from the finger bowls, which were passed before and after the meal. Keikiwai was hungry, and he enjoyed this chance to eat certain kinds of food which were tabu for the common people. He had roast pig and dog, many kinds of raw fish, pink poi, baked sweet potatoes with red salt, luau, sea urchins, crabs, and kulolo, which was a taro and coconut pudding. After eating he took a sip of awa, then hurriedly seized a calabash of water and gulped it down. " What bitter stuff!" he said to himself. "I hope that my being a chief will not make it necessary for me to drink it." Keha had planned to have a grand hula after the luau. "We must not stay," said Kaolani, "for my kahuna says that the gods favor an early departure." Keikiwai rushed forward to launch the canoe, but his father stopped him. " You are a royal guest. Let your retainers wait upon you." Then, seeing the young man's look of disappointment, he added: " There are many kinds of work that a chief can do. At home you can build canoes, and fish, and swim. The people are proud of a chief who can excel in doing things." It was late at night when the royal party reached home, but all the people were on the beach to greet them. They fell prostrate before Keikiwai also, for they could tell at once that he too was a chief. Manuia's family had lived in one house. In Keikiwai's new home there were so many houses that he was confused. He soon learned that he must keep out of the women's eating house and the house for tapa beating. But the heiau, the men's eating house, and the sleeping house were all open to him. It was not long before he got used to his new home. Keikiwai never tired of having his father tell him stories. He asked many questions about Kahiki, and learned that he had a brother who was still living in that strange country. This made Keikiwai resolve that when he was able he would go back to Kahiki and bring his brother to live in Hawaii. "Many of the chiefs who came from the South Seas were warlike," said Kaolani. “They took land away from the native chiefs and caused many cruel wars. I settled in this valley, where the people were without a chief, so they were glad to see me. The native chiefs have formed a society called the aha alii, to protect each other from the unworthy. When you grow to be a man, if you are brave, you may become a member." Keikiwai had been taught to be a brave warrior, and he felt anxious for the time to come when he could have a hand-to-hand contest with a rival chief, and grasp the palaoa from the dying man's neck. But the stories of Kahiki set him to thinking. He began to feel that a daring voyage in search of his long-lost brother was better than fighting. " When I am a chief," he said, " I will build a big double canoe and

bring my brother back with me."

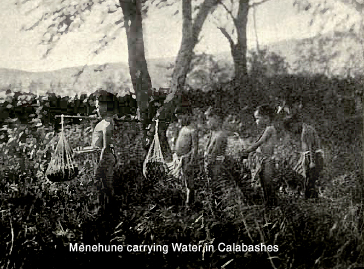

A long time before Keikiwai lived people were making journeys back and forth between the different islands in the Pacific Ocean. In time they reached all of them. Large double canoes were built for long voyages. The trunks of two trees were hollowed out and fastened together by crosspieces upon which a platform was raised. Sometimes the canoes were made of planks joined together. The paddlers sat in the canoes, and the passengers of rank were made as comfortable as possible upon mats spread out over the platform. A three-cornered sail was made of strips of matting and was a help to the paddlers. These canoes were from fifty to a hundred feet long and six or eight feet deep. A large company of people went on these voyages. The chief took his family, retainers to wait upon them, priests with their idols, musicians for entertainment, a pilot, and the paddlers. Enough food was taken to last for many days. The pigs, dogs, and hens were carried alive, while the pandanus and breadfruit were preserved in rolls of matting. Gourds served as water bottles. Many times these bold seamen were blown upon new islands by a storm or by a strong current. After going once the pilots learned the way, so that they could travel back and forth. The paddlers kept time to music and followed the direction which was signaled by the pilot with a bunch of grass. He steered partly by making a definite angle with the currents caused by the trade winds, but his surest guide was the stars. Sometimes as many as fifteen canoes would form a squadron. Then the pilot in the leading canoe would guide them all. In the daytime they spread out in a broad line so that they might not miss the islands, but at night they kept close together to avoid separation. About fifteen hundred years ago a bold seaman named Hawaii-loa reached the Hawaiian Islands, sailing from the west. Many people believe that he came first and named the islands after himself, and then returned for his family so that they could all make the new country their home. He may have brought the first large gourd and planted it ; certainly that variety is not found in the South Seas, where most of the people came from. Wakea and his wife Papa came also in those early times. Legends tell us that they came from Savaii in Samoa, that they named the islands after their old home, and even that they created the earth. They introduced the tabu system. The tabus were many laws, mostly foolish ones, which the common people had to obey. There were also tabus for the chiefs and priests, but these were not so many in number. If the tabus were broken the gods were supposed to be angry, and the offender was put to death by order of the priest. Often there was a reason for the first tabu, as, for instance, one upon food that was scarce, but the tabu was kept after the food became plentiful. These tabus made it easy for the chief and the priest to have all the power in their own hands. For many years no more people came to the Hawaiian Islands. At this time, so the old legends tell us, the Menehunes, or fairies, lived in the forests, and came out stealthily at night to build heiaus and fishponds and canoes.

Paao was a priest who came from Upolu in Samoa. His voyage is important because he made many changes in Hawaiian customs. He brought new gods and more tabus. He brought the puloulou, or tabu sticks, and changed the shape of the heiaus, making them four-sided instead of triangular, as they had been before. He built one in Kohala and another in Puna, both upon the island of Hawaii. He found no chief of high rank in the new country, so he returned to Samoa and brought back a chief named Pili, who is supposed to be the direct ancestor of the Kamehameha family. Moikeha was a famous chief. He sailed from Hawaii to the south, and probably visited the Society Islands. Upon his return he left his adopted son Laa in the strange country. Later on, his son Kila was sent to bring Laa back to Hawaii. Laa-mai-Kahiki returned and brought the first kaekeeke, a large drum made from a hollow section of a coconut tree, and having one end covered with shark's skin. Years afterwards Moikeha's grandson Kahai took a journey to the South Seas, and returned with the first breadfruit trees, which he planted at Kualoa on Oahu. These were only a few of the many travelers. Not only did they bring new plants and other things, but they changed the ideas of the people.

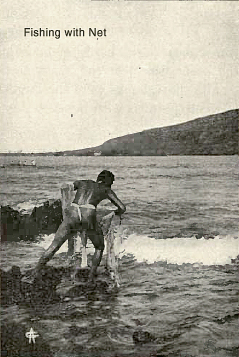

Because the people lived near the sea and needed fish for food, they became expert fishermen. They learned the haunts and habits of all the fish, also the location of rocks and shoals. They fished with hook and line, with nets, with spears, with fishing sticks and fishing baskets.

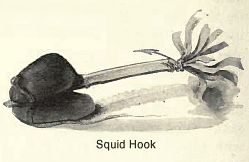

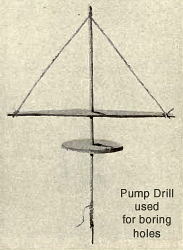

Fishhooks were made of bone, shell, ivory, or tortoise shell, and the only tool used in shaping them was a stone file. Sometimes bone and shell were used together, in which case holes were bored with a pump drill, and cord was drawn through to tie the parts together. The hooks were of different shapes and sizes for different kinds of fish. The barb of the hook was sometimes inside, sometimes outside, and sometimes there were barbs in both places. In some hooks the point was near the shaft, and in others it was not. The shark hooks were the largest ones, and were often of wood, pointed with bone. For catching squid, a shell and a stone sinker of about the same shape and size were fastened upon opposite sides of one end of a stick. A bone hook at the other end was concealed by leaves. The cord came through the shell.

Fishlines were made of olona cord. The kaa was a slender cord fastened securely to the shank of the hook, and to it was tied the ako, or line of heavier cord. With a bamboo pole, and a reel made of the neck of a broken gourd bottle, the fisherman of long ago was as well equipped as the average boy of to-day. Nets People often used to fish with nets made of olona cord. The olona was a shrub which grew wild in gulches and was often cultivated by the people. It can be found today growing wild upon Tantalus, the highest mountain in the Koolau Range, and in other parts of the islands. The fibers were used for cord.

These nets were drawn into large circles in the water and held up with sticks. At the top were floats of hau or of wiliwili, and at the bottom were stone sinkers. Fish were driven into the enclosure with ropes, or with branches having

a fringe of leaves tied at intervals. Bag nets had wooden rims and

handles, and were used to scoop up the fish.

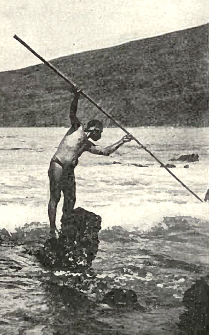

One of the most exciting ways of fishing was with a spear. This was a pole of hard wood six or seven feet long and pointed at one end. Sometimes several points were tied to the end. Spears were used when men dived under water as Keikiwai did when he killed the shark. They were also used to spear the fish in shallow water at night. In that case a torch was carried to attract the fish.

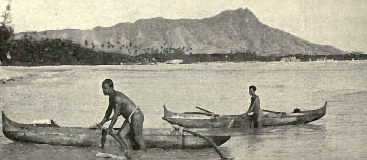

The making of a canoe was important, and needed the favor of the gods. So the canoe builders went first to the kahuna, who offered sacrifice and prayers to different gods. The kahuna then went with the men to help them find the right tree in the forest ; sometimes they climbed several thousand feet above sea level before they found it. For the best canoes he chose koa, which is a hard wood. He watched the elepaio, or woodpecker, and chose some tree that the bird did not bore into. This was rudely shaped, and then ropes were tied to it, and it was dragged down to the seashore. The canoe was made long and narrow so that it would go swiftly. It was hollowed out with a special right-handed or left-handed adz which had been invented by one of the canoe gods.

The ama, or outrigger, was a steadier, made of a curved log of wiliwili,

which was fastened to the canoe with iako, or branches of the hau tree.

Most of the canoes were less than 50 feet long. The fishing canoe of

Kamehameha V is in the Bishop Museum. It held four men besides the king,

and its dimensions are: length, 35.5 feet; depth outside, 27 inches;

inside, 23.5 inches; width outside, 23 inches; inside, 17.5 inches;

center of canoe to center of outrigger, 10.7 feet. The paddle was

usually 5 feet long, the blade 12 x 20 inches. The launching of a canoe needed the services of the kahuna. A sacrifice was offered, and then the owner and the kahuna stood at the bow of the boat. The latter recited a long prayer while the canoe was being launched. Any noise at that time was a bad sign ; perfect silence meant that the canoe was safe.

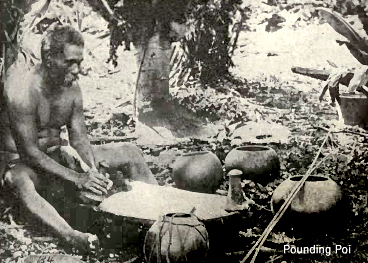

The cultivation of it required much labor. Upland taro was raised in dry soil, but the most common variety grew in wet soil. When the farmers started taro patches they divided the land near a stream into squares arranged in terraces so that the water could run from one to the other. Then these patches were separated by banks of earth and stones, and the surface was trodden down to make it water-tight. Water was carried from the stream by means of ditches. After the weeds were pulled out, the ground was soaked and harrowed, and the huli, or top sprouts, were planted in rows in the muddy soil. When the taro was well started, water was let in, and kept there until the taro was ripe. For six months it was weeded, but after that, weeding would have injured the plant. In twelve or fifteen months the leaves began to turn yellow. The people first trampled between the plants to loosen the roots, and then pulled them up. The leaves and roots were cut off with a sharp shell knife, and the stem with the new shoot was thrown on the bank for the next planting. People who lived on the kula, or dry lands, depended upon upland taro and sweet potatoes for food. The upland taro grew upon dry soil and needed no special watering. The tool for digging was the o-o, a stick of hard wood sharpened at one end. The stems were planted in rows. There were many varieties of sweet potatoes. After planting them in hills the family would sometimes leave them to grow without any attention, and go off to visit their friends. In four or five months they would return to find that the crop was ripe and ready for eating. Then it was their turn to entertain visitors.

The Hawaiians made fire by friction. They made a groove in a small stick of soft dry wood, usually from the hau tree. Inserting the point of a small sharpened stick of hard wood into the groove, they rubbed it quickly back and forth. In a short time the wood was charred, and in about a min ute smoke began to come and a tiny flame appeared. This was fanned until it set fire to the end of a roll of twisted tapa.

Banana stumps were pounded flat and placed upon the hot stones. Then the food, wrapped in leaves, was put between layers of banana or ti leaves. These were covered with about six inches of leaves and dirt. A small opening was left for water to be poured in to steam the food. Taro was cooked in different ways. The root, baked in ti leaves, was eaten as a vegetable. Luau, or Hawaiian spinach, was made from the young leaves baked in ti leaves.

Besides being necessary for cooking, fire was also used to give light and to dry out the house during the rainy season. Lamps were lava cups filled with oil and had tapa wicks. Candles were strings of kukui nuts, ten or twelve nuts being strung upon the midrib of a coconut leaf. The top one was lighted first, and burned about three minutes. Then the candle would be inverted to set the next nut afire, and the burned nut would be knocked off. Torches were made of four or five candles fastened together in pandanus leaves. In damp weather the fire was built in the center of the room upon stones, and the smoke escaped through the doorway.

The Hawaiian women had one advantage in growing their own dishes. They

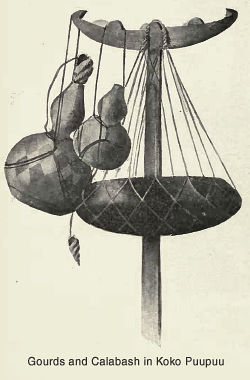

often tied bandages on the young fruit and made it grow The gourd was light and durable and had many uses. The bottle gourds with long necks held water at home, while the short-necked ones served the same purpose on journeys or in the canoe. Sometimes the neck of a bottle was filled with loose fibers and served as a strainer. The large gourds were used to make calabashes for holding food, and also as trunks, and for drums, rattles, and the like.

To make a calabash, a block of wood, carefully chosen and roughly trimmed, was soaked for months in mud or in a stream of water. Then the outside was shaped with a stone adz. It was polished first with coral, then with smooth stones, and lastly with dried breadfruit leaves. This gave it a beautiful finish. Finally the core was cut out with a small stone adz, leaving the walls less than an inch thick. Calabashes were made of many varieties of wood and in many shapes and sizes. Some held only a pint, others as much as ten gallons. Bowls, or calabashes, held poi, pudding, and other food. Finger bowls, used by the upper classes, had a projection to remove the sticky poi from between the fingers, which were used as fork or spoon. Other finger bowls had a compartment for water, and one for leaves upon which the fingers were dried. Flat dishes for meat occasionally had carved images at the ends. Spittoons were made with handles. People today appreciate the beautiful handwork on these old calabashes and pay much more for them than for the modern machine-turned ones. Some of them are worth a great deal of money.

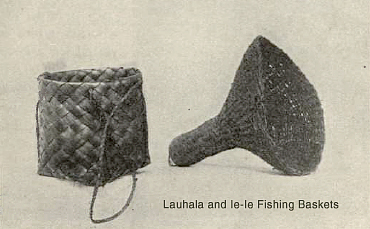

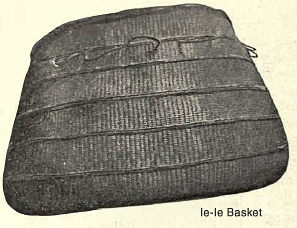

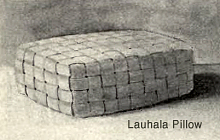

A long time ago the people made baskets out of ie-ie roots. The few of these that are now in the Bishop Museum show beautiful workmanship. Sometimes a basket was woven tightly over a gourd. When baskets were made from the coconut leaf, the midrib was split to form the top, and its end was the handle. The leaf was split and woven. The lauhala baskets are very light and durable, but they are not so beautiful as the old baskets were. The leaves of the hala tree were dried, then cut into strips and carefully scraped with a shell scraper. They were plainly woven.

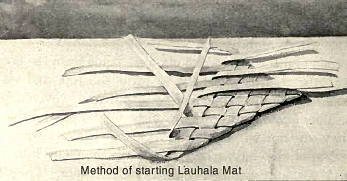

The most common variety of mats were made of lauhala. The leaves were prepared as for baskets ; then the women wove the mats by hand, beginning in one corner and working diagonally across. This plain weave could be skillfully patched by weaving in new strips. The makaloa mats were more beautiful, as well as stronger and firmer, than the lauhala ones. The makaloa sedge grew in marshy places on Niihau and Kauai. The mats had to be woven of young sedge. The stem was straw-colored, with its lower portion red. Other colors were made with vegetable dyes.

Captain Cook saw the following varieties: a white mat with red stripes and figures interwoven on one side ; a mat of pale green spotted with squares of red; a straw-colored one spotted with green ; and one made of beautiful stripes of red and brown.

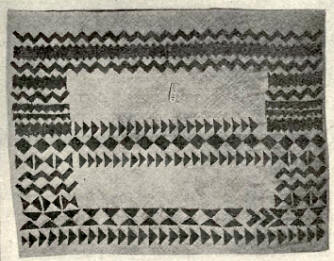

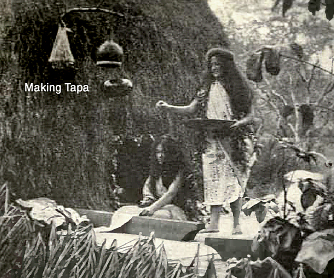

In Hawaii the wauke fibers were generally used. The wauke was found wild, but it grew best when it was cared for. Slips were planted here and there between the rocks. As the shrubs grew, their branches spread. A year or two after planting they were cut down by the men, and the bark was divided into long strips. Women rolled these strips with the inside surface exposed so as to let the sap evaporate, and then, having scraped off the outer bark with a sharp shell, they soaked the bundles in the stream. After soaking, the tapa was beaten on a smooth stone with a round mallet; this felted the fibers together. When it had been soaked again, it was beaten on a wooden log with a mallet having patterns on four sides, to give it an even texture. All this time it was kept moist with water. The tapa could be made any size or shape by overlapping strips and beating them together. Tapa was bleached in the sun to make it white. Coloring matter was made from soil, or from berries or roots pounded in a stone mortar with a vegetable oil and mixed with water. Tapa was colored by soaking it in this dye. A perfume was made of sandalwood, or of pandanus seeds steeped in a vegetable oil. Tapa soaked in this became waterproof, but it did not last long. There were many different patterns upon the tapa, made up of lines and figures without any special meaning. These patterns were stamped with a bamboo stamp or painted with a brush. The brush was a piece of bamboo split at one end. Another kind of brush was made from a section of the pandanus fruit frayed at one end. The brush was dipped into a calabash of paint, held over the tapa in the right hand, and pressed down with the left hand. It was so well guided by the eye that one cannot tell where the parts were joined. Sometimes a rope, a sea urchin, or a breadfruit leaf soaked in paint was pressed upon the tapa. The women had a grass house, built especially for tapa making, which was tabu for the men ; but in pleasant weather they preferred to work out of doors. One woman often worked by herself, with her children perhaps to help her. Sometimes the women would signal from one valley to another by a special way of beating. Tapa beaters worshiped the goddess Lauhuki, and offered sacrifices to her so that she would help them in their work.

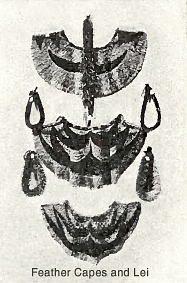

The capes, helmets, and idols were made by tying the feathers to olona netting, which was the work of women. The rows of feathers were so close together that the work looked like the breast of a dove. The edges were kept smooth by reversing the feathers at the border. The capes were shaped by fastening small pieces of netting together, and then the feathers were tied on. Some capes were made of one color, others had a border of a contrasting color, while some had crescents or figures of still was drawn first upon white tapa, and circles were made true with a cord. The highest chiefs wore long capes which reached to their ankles, while the lesser chiefs wore short capes over their shoulders. Many of the capes are now in the Bishop Museum and are worth thousands of dollars. The most valuable one is made of the orange-colored feathers of the mamo, a bird which is now extinct. It was worn by Kamehameha I, and was at least one hundred years in the making.

The feather idols were made in the same way as the helmets, and hoops were put inside to make the head firm. The faces were hideous with their wide, gaping mouths lined with shark's teeth.

These feathers were so valuable that when not in use they were taken from the handles and carefully stored away in calabashes. A lei was made by tying small feathers tightly to a strong cord of oloua. Usually the feather lei was all of one color, but sometimes there were bands of red and yellow. These lets were worn only by women of the nobility and were carefully kept in joints of bamboo when not in use.

The people did not need much clothing in that mild climate. They used tapa and matting for clothes, and shells, seeds, or flowers for decoration. Women wore the pau, which was made from a piece of tapa about four yards long and one yard wide. It was made in several layers, often beautifully colored red, yellow, or black. The pau was usually worn as a short skirt. It was wound around the body several times, and the end was tucked in at the waist or drawn up over one shoulder. A cord at the waist made it more secure ; and when a smooth pebble was rolled up in the top edge and tucked under the cord there was no need for buttons and buttonholes. A convenient way to put on the pau was to spread it out on the grass and roll up in it.

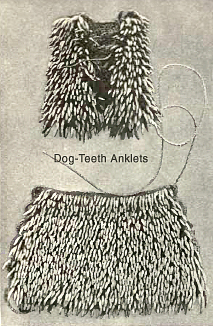

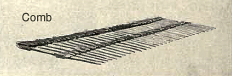

Some of the people tattooed their bodies. They got the idea from the natives of the South Seas. They thought because it attracted attention that it was beautiful. All the people liked to wear leis, or wreaths, which they made from flowers, vines, seeds, shells, shark's teeth, and even from human hair. These they wound around their heads or about their necks. Bracelets and anklets were made of dog's or hog's teeth or of shells. The nobility wore the feather capes and helmets and the necklace with palaoa (a hook-shaped pendant of ivory or whale tooth fastened to many cords of closely braided human hair) on special occasions. These things were a sign of rank.

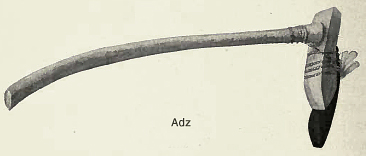

The adz maker first tested his stone to be sure that there were no flaws in it ; then he separated the flakes from the rock with a pebble for a hammer. With a clinkstone chisel he chipped it into shape and then ground off the edges with a stone grindstone. The handle was made later from a branch of hau or of other wood. Notice in the picture how a piece of tapa is between the adz and the handle, and how securely it is tied with olona or with coconut fibers. The art of adz making was a secret handed down from father to son. It was protected by special gods, and each factory had a heiau, or temple, in which sacrifices could be offered to these gods. The largest adzes, weighing as much as twelve pounds, were used for felling trees. Different sizes were needed for hollowing canoes, building houses, etc. Some were less than an ounce in weight and were used in carving idols.

The chief had carpenters among his retainers. When a new house was built they acted as lunas, or overseers, and the common people did the work without pay. The strong men brought the timber from the forests for the posts and framework. The women and children gathered a huge pile of grass and ferns for thatching, and the old men made a cord of coconut fibers and wound it into balls to be used for tying the parts together. In some houses a floor was made of smooth pebbles. The posts for the two long sides were put in parallel rows, perhaps five in a row. The main poles at the ends and midway between the others were higher and notched at the top to fit the ridgepole which connected them. Small poles connected the ridgepole with the side posts. Sticks were put erect and crosswise between the posts and tied securely. The house was sometimes thatched with leaves, but more usually with grass. Small bundles were tied to the framework so that the roots turned upwards and were inside. The thatching was done from the bottom upwards. Carpenters finished the edges with fern stems. The doorway was low, and had grass carefully braided around the opening. The door was of rudely cut boards fastened to cross boards with wooden pegs. Sometimes the front rafters were extended and fastened to posts, making a lanai, or porch thatched with leaves. Often the lanai was separate from the house. The common folk had houses made just like those of the alii, or chiefs, only they were smaller, fewer, and not so well finished. Each family had to build its own house, unless the neighbors were willing to help. In each village was a special carpenter to finish the edges of the roof and the corners; he was paid in advance with presents. It was not long before a grass house had to be rethatched, and in a hard Kona storm the roof often leaked. House building needed the favor of the gods, requiring the services of a priest, for which he received presents, the people building the house, he making offerings and prayers to the gods. Often the priest was the first one to sleep in a new house ; it was then his custom to offer prayers to keep out the evil spirits.

Fishlines were stored in bottle gourds with long necks, and leis in joints of bamboo. The walls were ornamented with useful things such as spears, daggers, adzes, bows and arrows, o-os, and brooms. The kahili, or broom, was made of the midribs of coconut leaves tied together at one end. Women squatted down when they swept.

The old songs, or meles, had neither rime nor meter. The people sang deep down in their throats, and used only two or three tones. A good singer had to be able to breathe deeply, for the phrases were very long. These meles were composed by the bards. They taught them to their sons, who passed them on to their children, and in that way many of them have come down to us. It is only through these songs that we know anything at all about the life of the past. The songs were made up of flowery words, and were prayers, dirges, love songs, and name songs which were composed at the birth of a chief to tell who his ancestors were. We know that the first drums were brought from the South Seas by Laa-mai-Kahiki. Other and smaller drums were made of coconut shells or wooden calabashes covered on one side with shark's skin. The Hawaiians had wind instruments also. Perhaps the thought of making such instruments came to them when they heard the wind blowing through the reeds.

Perhaps the twang of the bowstring might have led people to think of string instruments. The ukeke was a bow of flexible wood having several strings of coconut or olona fiber. In those days people were as fond of dancing as they were of swimming. Public dancers were usually a few women who were trained for this work. They wore decorated pau, leis of flowers and vines and shells around their necks or on their heads, and bracelets and anklets of teeth. The dancers kept time to music and often acted out the song as it was chanted. At first the hula was in honor of the gods or in praise of the chiefs, and the dancers worshiped the goddess Laka. Later its purpose was changed and it became corrupt. The old-time Hawaiians were fond of games, and their outdoor sports made them strong and alert. The games in the water helped them to be better fishermen. Little babies were taught to swim, and they always liked to play in the water. Boys became experts in jumping from high precipices, and in diving, floating, and swimming under water or with their feet interlocked. Surf riding is still the national sport. Many of us know by experience how hard it is to keep our board on the edge of the wave and to steer it so that the wave carries us along. In those days the boards were larger, and riders could change their position while surfing. They liked to stand as they rode in. Sometimes they rode the surf in frail canoes, which is the most popular way at the present time. The wooden surf boards were painted black. After being used they were dried in the sun, rubbed with coconut oil, wrapped in tapa, and hung inside the house.

Maika was played upon a similar kahua with a polished stone called the ulu-maika. This stone was circular, thicker in the center so that it would roll well. One game was to roll it between sticks which were thirty or forty yards away. Sometimes the players rolled it as far as possible, the best ones making a distance of about one hundred rods. After a game the ulu-maika was carefully dried and wrapped in tapa.

Konane was a little like checkers, only more difficult. The checkers were black and white pebbles, and the papamu or board was usually of stone, with indentations for the squares. Kamehameha I was fond of this game, and often played for hours at a time without saying a word. He was so skillful that no one could win from him.

Children had many games of their own much like the games which you enjoy. They played with jackstones and flew kites. Panapana was played by bending the midrib of a coconut leaf into a bow and then letting it snap as far as possible. Boys often turned somersaults in the grass or on the sand. They could tie many kinds of knots, and played a game called hei that was like cat's cradle.

Back to Mo`olelo (myths/stories) and Mēheuheu (customs)

Long ago, in the fifteenth century, a little boy named Umi lived in a village of East Hamakua on Hawaii. His mother was of low birth, and he was brought up like the other boys of the village. But he was different from them, for he was larger and stronger, and he became the leader in all the games.

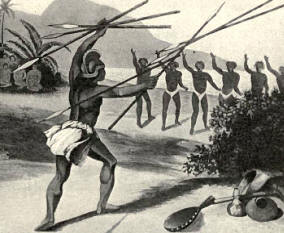

"I have a secret to tell you," she said. " Your father is the alii kapu, or highest chief of Hawaii, and his name is Liloa. He left these signs of royalty for you to have when you grew to be a man. Show them to him, and he will know that you are his son." Umi decided to go at once to Waipio, where Liloa lived, and force his way into the presence of the alii. This required great courage, for Umi knew that if Liloa did not recognize him, he would be killed. It was a long walk from Hamakua to Waipio. When he arrived, hot and tired, he decided to make himself known at once. He climbed over the fence, and entered the palace through Liloa's private doorway, in defiance of the tabu sticks at the entrance. The retainers rushed after him to kill him for his daring, but he ran faster than they. Once inside, it was not difficult to recognize the alii and Umi rushed forward and jumped into his lap. Liloa was angry until he noticed the malo and the sacred palaoa which Umi wore. "What is your name? " he said. "Are you Umi? " “Yes," was the answer, as Liloa held him close. " I am Umi, your son." “Where is your mother?" "It was she who sent me to you." Liloa publicly acknowledged Umi as his son. The lad lived at court and had many retainers to wait upon him. He and his half brother, Hakau, both fond of games, were leaders of the young chiefs in wrestling, drawing the bow, and in hurling the pololu, or long spear. When Umi led one party and Hakau the other, the side which Umi led always won. That made Hakau jealous of his brother. When Liloa died he left the throne to Hakau because he was the oldest son. Umi was to be Hakau's prime minister. Upon his deathbed, Liloa said, " Thou, Hakau, wilt be the chief ; and thou, Umi, wilt be his man." Hakau was a cruel alii, and treated Umi so badly that he left Waipio and lived in secret with people who did not know his high rank. Hakau grew worse and worse, until at last he insulted two old men who had been advisers of his father. They found out that Umi was at Laupahoehoe, so they complained to him and induced him to raise an army and march against Hakau. The latter was killed, and the people welcomed Umi as their deliverer and chief. Let us see how much power a chief had. He was like a god to the people, who got down upon their hands and knees when he appeared. He owned all the land and everything upon the land. His power was as great as that of Pharaoh in the days of old. One man could not look after all the people, so Hawaii was divided into six districts, with a chief at the head of each. These chiefs divided the lands in their districts among chiefs of lower rank, and these divided among the common people, who did all the hard work. The common people had to pay taxes in presents to the chief. Once a year a taxgatherer was sent out to collect mats, poi, tapa, hogs, and other products. He kept a record of the wealth of the land and of the taxes that each man paid, by making loops and knots of different kinds upon long cords. Strange to say, he was just as accurate as we are to-day with our written records. When the chief wanted laborers to build a canoe or a palace, or to work upon his taro patch, the people had to leave their own work and do his bidding without pay. Moreover, offerings had to be made to the priest and to the many gods. When all this had been done, the people could have what was left for themselves. When Umi came to the throne a cruel cousin of his ruled on the western coast. Umi defeated him in a battle fought on the highlands between Mauna Loa and Hualalai. In memory of this battle Umi had seven pyramids and a heiau built upon the site of his victory. Six pyramids represented the six districts, and each man brought a stone; the seventh one was for himself, the heiau being in the center. The ruins of these huge buildings can be seen to-day ; they are called Ahua a Umi, or the "Heaps of Umi." Umi made his headquarters in the mountains, and hence was called the Mountain King. Umi changed the capital from Waipio to Kailua in Kona, where part of his time was spent. He married the daughter of the king of Maui, who sent a large fleet of war canoes to escort her to Hawaii. After her father's death her older brother, who took the throne, was cruel to the younger brother. In behalf of the younger brother, Umi took a fleet of war canoes and landed at Hana. He captured the fort of Kauwiki, on the top of a high hill. This fort has been the scene of many battles since that time, but only the bravest chiefs have been able to take it. Then Umi met the Maui king in battle, defeated him, and gave the throne to the younger brother, who is remembered to-day because of the paved road which he built around East Maui. Remains of this road can still be seen.

Kamehameha I was born one stormy night in November, 1736, at Halawa, Kohala. People listened to the thunder with awe, and said that the gods were trying to tell them that they had sent a great warrior chief into the world. We know little about his boyhood. One story tells us that when he was a wee baby he was stolen from his mother's side in the night and carried away by a chief named Naeole. Although this chief kept him in secret, the king of Hawaii, Alapai, found out where he was about five years later, and ordered the child to be brought to him. Nevertheless, Naeole, according to the tradition, brought another child and kept Kamehameha. Part, at least, of Kamehameha's boyhood was spent at his home in Halawa, Kohala. There he and his companions played many games. He grew to be strong and fearless, and led the others in wrestling and in hurling the spear, also in surf riding and coasting. He was not ashamed of work. He had a field called Kamehameha, and in it he planted taro and sweet potatoes. His friends followed his lead, and each one had a field named for himself. He delighted in overcoming obstacles. At Halawa a steep precipice about one hundred feet high made it impossible for people to draw up their canoes. So he and his companions cut a road to the sea through the hard rock with no tool better than the stone adz. Another time they dug for water. They were through several layers of hard rock before they would give up, and then only because it was impossible to succeed. A grove of noni trees was planted by Kamehameha "before his beard had grown." The fruit and leaves are valuable as medicine, and the sap makes a yellow dye used for coloring tapa. Near his home was a heiau where he worshiped the terrible war god Kukailimoku. He was careful to keep the tabus and to favor the gods. His father, Keoua, was half brother to the king, Kalaniopuu, who became ruler when Alapai died. This king asked his young nephew to help him in his many fierce wars. Kalaniopuu had to fight against powerful chiefs on Hawaii to get his kingdom. He fought with the kings of Maui for possession of the fort of Kauwiki, which he held for twenty years. At last Kahekili, the king of Maui, kept the soldiers from getting water until they had to surrender. Let us leave Kamehameha I and go back to the time when Umi's son was ruling. It was then that a strange ship was wrecked off the rocky coast of Keei in South Kona, Hawaii. The captain and his sister were the only ones who were saved. In thankfulness they knelt upon the beach, and stayed so long in that position that the people named the spot Kulou, which means " kneeling." The natives received them very kindly, and they spent the rest of their lives as Hawaiians. At that time the sixteenth century many Spanish ships were sailing the Pacific. We believe that this ship was one of those which were lost in severe storms and never heard from. In 1555, not many years later, another Spanish ship stopped at the islands on its way from Mexico to the Philippines. Juan Gaetano, the captain, located them upon his chart, but he kept his discovery a secret. Now let us return to our story of Kamehameha I. It was in 1778, while he was with his uncle, that the islands were discovered by James Cook, an English naval captain, on his way north from the South Seas. This discovery was most important, because he made the islands known to the rest of the world. He saw Oahu first, then sailed on and landed at Kauai and also at Niihau. The natives were filled with wonder at sight of the strange ships, and one of them exclaimed, "It is a forest that has moved out into the sea." The two ships stayed only long enough to trade nails and pieces of iron for food and water, and then sailed on to the north. Messengers were sent to the other islands to tell of the strange visitors. Kalaniopuu was on Maui fighting against Kahekili when the news reached him. One of the messengers said: " The men are white; their skins are loose and folding ; their heads are strangely shaped; they are gods, volcanoes, for fire and smoke issue from their mouths ; they have doots in the sides of their bodies into these openings they thrust their hands and take out iron, beads, nails, and other treasures; and we cannot understand their strange speech." The ships came in the following year to spend the winter in the sunny isles, anchoring on the west coast of Maui. Kalaniopuu was still there, and Kamehameha was with him. Several of the chiefs boarded the ships, and Kamehameha the fearless accepted an invitation to stay all night. The ships then went on to Hawaii and anchored at Kealakeakua Bay. The natives believed that Captain Cook was their god Lono, who had left the islands many years before and had promised to return. Captain Cook allowed them to worship him and received rich presents, giving little in return. Kalaniopuu shortened his stay upon Maui. Upon his arrival at Kealakeakua he visited the ships formally. His party were in three large double canoes. First came the one with the king and his chiefs dressed in bright red and yellow feather cloaks and helmets, and carrying spears. In the second canoe was the high priest, guarding the brilliant war god, and the other priests carrying more idols. The last canoe was filled with pigs, coconuts, and breadfruit. The fleet paddled around the ships while the priests chanted prayers and hymns. Captain Cook received them on shore. The king presented the captain with several beautiful feather capes, a helmet, and the food that was in one canoe ; in return he received from the captain a linen shirt and a cutlass.

Captain Cook had made many daring voyages for England. About fifty years after his death the English government sent money for the erection of a monument to his memory. It stands at Kealakeakua Bay, as near as possible to the spot where he fell Because of Cook's sudden death it was more than seven years before any other ships visited the islands. His discoveries, however, showed the people of England and France that they could make money by getting furs from the Indians along the west coast of America and selling them in Canton, China. English ships were the first to stop at the islands on the way across the ocean. They found it a convenient place to get fresh water and provisions. Soon many ships came, especially in the winter, on their way to China. These visitors taught the people many new things. Sometimes they took Hawaiian boys as sailors to strange lands. Many of the sailors were rough men who sold firearms and strong drink, while others brought plants and animals and helped the natives to learn better ways of living. Captain George Vancouver had been with Captain Cook ; fourteen years later he came again, and in two years made three visits. We have not gone quite so far as this in our story of Kamehameha, but let us glance ahead while we are telling about foreign ships. When Captain Vancouver came he sailed along the Kona coast. Kamehameha had defeated his enemies on Hawaii and was on the other side of the island. The English captain visited several islands. On Hawaii he was received by Kaiana and Keeaumoku, chiefs under Kamehameha, and gave them presents of orange trees, grapevines, and other useful plants and trees. On Kauai, the young chief Kaumualii visited his ship. The second time that Vancouver came he brought some cows and sheep from California. He gave Kamehameha a bull and a cow, strange animals to the Hawaiians. Vancouver anchored at Kealakeakua Bay and was kindly received by Kamehameha, who saw from the first that much could be learned from foreigners. Vancouver liked the king, whom he remembered from his visit with Cook. He had thought at that time that Kamehameha had a savage expression; but he had changed, and his face showed that he was cheerful, generous, and good. Kamehameha visited the ship formally. With eleven double canoes under his command, he stood in the bow of the largest and foremost one, where he could be seen by all. He wore the same linen shirt that Captain Cook had given to Kalaniopuu so many years before, but over it was the long feather cape made of choice mamo feathers which is now in the Bishop Museum. His height and dignity were increased by the gorgeous helmet which he wore. He fixed his eyes upon the paddlers, who kept perfect time as they circled the ship ; then, at a command from him, all but the largest canoe drew up in line at the stern of the ship and remained motionless. At another command the thirty-six paddlers in his own canoe rowed rapidly until they were exactly opposite the gangway, and then stopped suddenly just in time for the chief to step to the ship where Vancouver waited to greet him. On Vancouver's last visit he brought more cattle and sheep, and had Kamehameha put a tabu upon them to last for ten years. He would not sell firearms, and tried to stop the cruel wars, but in vain. His carpenters built for Kamehameha the first vessel constructed on the islands, the Britannia, which was only thirty-six feet long, but was of great value to Kamehameha when he set out to conquer all the islands. Vancouver promised to come again and bring missionaries to teach about the one true God, and workmen to teach the different trades. The chiefs on Hawaii had a council at which they put their country under the protection of the king of England. Vancouver's plans to return were never carried out, but Kamehameha did not forget them. Years later, when he was king of all the islands, he sent a present of a feather cape to King George III, and dictated a letter reminding the king that Vancouver had promised to send a man-of-war armed with brass guns and filled with foreign goods. Let us see what happened to Kamehameha after the death of Kalaniopuu, who had left his throne to his son Kiwalao. Kamehameha received second place and was to have charge of the war god. He had lands on the western side of the island. Kiwalao was a weak king and soon became jealous of his powerful cousin, so Kamehameha left the court and lived quietly at his old home in Kohala. It was not long before Kiwalao's uncle and brother convinced him that the division of the land was not fair, because Kamehameha had the Kona side, where the fishing was best. They joined against Kamehameha. One of the latter's friends warned him, and he raised an army to meet theirs. Kiwalao was killed in the battle of Mokuohai. It was nine years before Kamehameha got control of the whole island. He fought many wars against powerful chiefs, but at last he became high chief of all the island. He also fought long and bitterly against Kahekili, the Maui chief of whom we have already heard, but he could not get Maui, and Kahekili could not get Hawaii. It was then that Vancouver came and tried in vain to make these two kings friends. Kamehameha was not satisfied with one island. Many hundreds of years before, there had been a chief of Hawaii named Kalaunuiohua. He planned to conquer all the islands, and his large fleet of war canoes took Maui, Molokai, and Oahu ; but at Kauai he was badly beaten, and his plans to found a united kingdom fell to pieces. Now Kamehameha waited until the death of Kahekili before he raised a fleet for the same purpose. His war canoes stretched four miles along the shore, and in his army were sixteen thousand men. He had the aid of foreign cannon and firearms, and sixteen foreigners to handle them. It was the largest army that had ever been raised in the islands. They conquered Maui and Molokai without difficulty, but on Oahu a terrible battle was fought in Nuuanu Valley. We shall hear more of that battle later, but now it is enough to know that Kamehameha routed the enemy. The fleet, which now started for Kauai, was driven back by a storm. Another large fleet was raised, but this time a sickness broke out among the warriors and they could not go. Kaumualii, the Kauai king, planned to defend his island; later, however, he decided to offer it to Kamehameha. The latter said, "Keep it until my son becomes ruler, and then it shall belong to him." One chief on Hawaii rebelled, and Kamehameha I returned to that island and defeated him. Kamehameha had a way of making friends of his enemies. He gave the people peace and tried to have the country prosperous again, but of course the best land went to the chiefs who had been faithful to him. In many ways the government was much like that in the time of Umi, for Kamehameha owned all the land and had the powers of a feudal lord. He gave the highest offices to people whom he could trust. Chiefs who might become discontented were kept near him where he could watch them. He also had spies in different parts of his kingdom. We shall learn more later about the four Kona chiefs who had always been his best friends. He kept these for his chief advisers. His prime minister was Kalanimoku a chief who had once fought against him. Kalanimoku was chosen because of his ability, although he was a chief of low rank. Foreigners called him William Pitt, and he liked the name. Priests collected the taxes and saw that the laws were obeyed. The tabus were seldom broken, because fear of punishment had so strong a hold upon the people. There had never before been such good laws against theft, murder, and other crimes. The saying was that old men and children could sleep in the highways without fear. Kamehameha was always fair to foreigners ; he encouraged them to stay in his country and to teach his people new things. Kamehameha granted lands free from rent to foreigners if they would stay and cultivate them and bring in new plants and seeds. A Spaniard named Marin had a piece of land on which he raised many things. He had oranges, roses, pineapples, and vegetables. He brought the first mangoes, beans, figs, grapes, and avocado pears. The common natives worked small farms subject to the chiefs, and raised taro, yams, and sweet potatoes, as they had done for many years. They began also to raise Indian corn and vegetables. Kamehameha himself was sometimes seen at work in the field. Long ago the only useful animals were pigs and dogs. Foreigners had brought in cattle, sheep, and goats, and Kamehameha had wisely put a tabu upon the cattle and sheep for a term of years. Before his death they had become numerous and supplied the people with mutton, beef, and milk. An American captain brought the first horses, and the people soon became expert riders. Kamehameha was fond of riding and kept five horses for his own use. Foreigners taught the different trades. The king had carpenters, masons, blacksmiths, bricklayers, and tailors in his service, most of whom had been American sailors. Some of these were hard workers, but many of them were lawless men who distilled liquor and did harm to the people. Kamehameha saw the advantage of trading, and soon learned the values of money, weights, and measures, so that foreigners could not cheat him. He encouraged ships to stop at the island. At first they came for supplies ; then they carried sandalwood from the forests and sold it in Canton. Pearls and mother-of-pearl were also exported. Kamehameha bought great quantities of foreign goods, which he stored in the two large stone houses near his home. Honolulu, in 1809, was a village of about a hundred grass houses. The only shade trees were the hau and the coconut palm. At Lahaina the king had a stone house built by foreigners, but in Honolulu he lived in a series of grass houses, which he -liked better. His home was on the seashore, separated from the public by a high fence mounted with sixteen guns. Shortly before the close of Kamehameha I's reign a fort was built at Honolulu at the foot of Fort Street. Russians had started to build a fort on Kauai, and Kamehameha, thinking that they had plans to take the islands, drove them away. John Young was an English seaman from an American vessel, who had been detained on the islands, and who had always been a great help to the king. He now advised the prime minister, Kalanimoku, to have a fort at Honolulu so as to protect the islands. The walls of the fort were twenty-five feet thick and twelve feet high. The cannon which surmounted them were of different sizes, as they had been bought from different ships. In the grass houses within the fort the business of the government was carried on. From the flagstaff waved the Hawaiian flag. At first, this resembled the British flag; but during the War of 1812 Kamehameha was told that Americans would think that he sided with England, so he changed the flag. The picture shows how it resembles both the English and the American flags. The eight red, white, and blue stripes represent the eight largest islands. One of the king's weavers was an English sailor named Campbell, who tells about Kamehameha's way of living as follows: "The king's mode of life was very simple ; he breakfasted at eight, dined at noon, and supped at sunset. "His principal chiefs being always about his person, there were generally twenty or thirty persons present; after being seated upon mats spread upon the floor, at dinner a dish of poi or taro pudding was set before each of them, which they ate with their fingers. This, fare, with salt fish and consecrated pork from the heiau, formed the whole of the repast, no other food being permitted in the king's house. A plate, knife, and fork, with boiled potatoes, were, however, always set down before Moxley (the interpreter) and me, by his Majesty's orders. The breakfast and supper consisted of fish and sweet potatoes. The respect paid to the king's person, to his house, and even to his food, formed a remarkable contrast to the simplicity of his mode of living. Whenever he passed, his subjects were obliged to uncover their heads and shoulders. hen his food was carried from the cooking house, every person within the hearing of the call Noho ("sit down"), given by the bearers, was obliged to uncover himself and squat down." Kamehameha had several residences, but the last seven years of his life were spent at Kailua on Hawaii. He died in 1819, when he was eighty-two years of age. People showed their grief in the old way, by being lawless, by knocking out their front teeth, and by wailing loudly. His bones were secretly hidden. Kamehameha I stands out as the greatest character in Hawaiian history. He did not break away from the old customs, but little by little he changed the manner of living and prepared the country for civilization and Christianity. He was ahead of his times, and may be said to connect the old and the new order of things. During the reign of Kalakaua, one hundred years after Cook's discovery, the government decided to put aside ten thousand dollars for a bronze statue of Kamehameha. A portrait of the king taken by a Russian artist, with pictures of fine-looking Hawaiians, was sent to an American sculptor in Italy, who executed the work. On the voyage to Honolulu the ship containing the statue was wrecked near the Falkland Islands, so a duplicate was made. It stands in front of the Judiciary Building in Honolulu. Years later the sunken statue was raised, and this is now standing in the courtyard in Kohala. At the base are four pictures in bas-relief. They represent canoes greeting Captain Cook at Kealakeakua Bay ; six men hurling spears at Kamehameha; a fleet of war canoes built for the invasion of Kauai ; and old men and children safe on the roadsides. Back to Contents Back to Royalty Pages

Keoua, a half brother of Kiwalao, was of higher rank than Kamehameha, He and his uncle, Keawe-mauhili, were the chiefs who had made Kiwalao anxious to take the best fishing grounds from Kamehameha. Keoua was the one who started the war by destroying property. After King Kiwalao was killed in the battle of Mokuohai, Keoua fled to Kau, and his uncle fled to Hilo and Puna. There were then three powerful chiefs, each anxious to get all the power. At that time Kamehameha was called to Maui. While there he received news that his cousin and uncle had quarreled, and that the uncle, Keawe-mauhili, had been killed in battle. Keoua, it was said, was planning to take Kamehameha's land, so the latter hurried home. Keoua was too powerful for Kamehameha to defeat. Something happened, however, which made Kamehameha believe that the war god and the volcano goddess were both on his side. Keoua's army, in marching from Hilo to Kau, had to pass the mighty volcano of Kilauea. Here was the abode of the dread fire goddess Pele. As they marched by, the army threw stones into the crater. The next day the earth began to shake, and flames, ashes, and stones were hurled into the air. The noise was much louder and more terrible than thunder. The army was in three divisions. The front ranks reeled to and fro as the earth shook, but no harm came to them. When the last division hurried on they came across the middle division, who had not been able to escape. They had all been suffocated by the poisonous gases. Keoua lost heart after that awful event. Kamehameha rejoiced that the war god favored him, and built a heiau in honor of this god at Kawaihae. Soon after this, Kamehameha sent for Keoua to come and make peace. They had been enemies for nine years. Keoua arrived in a large double canoe, but just as he was about to land, he was stabbed to death by Keeaumoku, one of Kamehameha's chiefs. Some of his followers were also killed, and the bodies were offered in sacrifice to the war god in the new heiau. We wish that he had been defeated in a different way, and that this stain could be removed from the character of the great Kamehameha.