Hawai`i Past and

Present

By WILLIAM R. CASTLE, JR.

New York—Dodd,

Mead and Company 1913

|

CHAPTER 6

Honolulu The American tourist to the Hawaiian Islands will probably take ship at San Francisco, although the steamers from Vancouver are also good. He must remember that from a United States port it is possible to sail to Honolulu only on a ship under American register, unless he has a through ticket to the Orient and plans merely to stop over. The first day or two out of San Francisco are usually cold, so that heavy wraps are essential, but as the rest of the trip is warm, rooms on the starboard side, getting the trade winds, are preferable.

After the hills of the Coast Range have dropped below the horizon there is almost nothing to see a whale perhaps, or porpoises, but no land and very rarely a passing ship. But to the man who has never been in the tropics the ocean, so utterly different from the North Atlantic, is a revelation. There usually are no waves, as the Atlantic traveler knows waves, but the whole surface of the sea sways gently in great, silent, lazy swells. Day by day the blue grows more intense until it becomes that brilliant, translucent, but seemingly not transparent, ultramarine that is seen only in tropical waters and that once seen is never forgotten.

On the sixth day there comes the restless feeling that one always has on approaching land. The ocean, near the Islands, loses its glassy surface, which, after a long time, is uneasily suggestive of the "painted ocean" in the "Ancient Mariner," ripples again as the ocean should, and breaks into spurts of foam. The cloud-bank ahead finally reveals the land beneath, and one sees the rocky eastern end of the Island of Oahu. To the left appears the long coast line of Molokai, but at no time near enough to be interesting, except as being more land. It is on the Island of Oahu, straight ahead, that attention is riveted, on the barren promontories, at the foot of which the surf marks its feathery, ever changing line. On the point reaching out furthest toward the east stands the magnificent Makapuu Point Light, installed in 1909, one of the most powerful lights in the world, and in a position where it is vitally necessary to mariners. All black this land looks, like rude piles of huge volcanic, storm-beaten rocks. The north side of the Island is shrouded with clouds, but, if the day is propitious, as it usually is, the clouds break again and again, revealing distant but enchanting glimpses of colour—the soft green of cane fields, the vivid yellow of salt grasses along the shore, and the purple blue of the precipitous mountains across which the trade wind is blowing masses of sparkling white and silver grey clouds. But these are only glimpses, lost as the steamer approaches the Island and, rounding the Point, proceeds westward along the southern shore.

Oahu geologically is made up of two ranges of mountains. Those in the southwestern part, the Waianae Mountains, form a group dominated by Kaala (4,040 feet), flat-topped, as though the original volcanic cone had been blown away, as it in fact may have been, since there are still vestiges of an ancient crater. The Koolau Range, forming the backbone of the Island, extends in an unbroken chain from northwest to southeast. On arriving from the north it is the geologically younger end of this range that one sees first, barren because not yet has sufficient time elapsed to allow erosion to do its full work of disintegrating the ancient lava and forming fertile soil. As the steamer rounds Koko Head, long and rounded, like a gigantic mound of desert sand, so named because of its blood-red colour in certain lights—koko means blood in the Hawaiian language—there come into view the shores of the great shallow bay of Waialae. Here, at last, is vegetation. The beach is fringed with cocoanut trees, and a little way back the land rises abruptly, breaking into deep, narrow, fertile valleys and rocky ridges that on their higher slopes lose themselves in the verdure of the mountain tops. After a half-hour skirting the coral reef that protects the bay from the great swells of the Pacific, the boat passes another promontory, Leahi, or Diamond Head, and the city of Honolulu comes into sight.

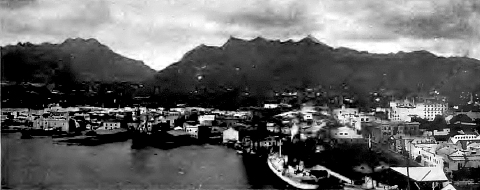

The tourist knows at last that he is surely in the tropics, knows, too, if he has travelled far, that nowhere is there a more beautiful, peaceful scene. The ocean outside the reef is blue—the same blue that it has been for days, but darker, so deeply dyed that it looks almost opaque, until one gazes straight down and catches the twisted sun rays that are gleaming far below the surface. The reef makes a sharp line of white surf, and beyond it the wide shoals are pink and green and buff, according to the nature of the sea-bottom and the angle of the light—a brilliant Oriental carpet along the shore. The mile or two of gently rising land between the beach and the spurs of the mountains is a mass of trees, the green line of them broken only by the roofs of the houses. This vegetation, a little monotonous in colour, as an artist would have made it to lead from the brilliance of the sea to the still more brilliant mountains, extends from the suburb of Waikiki, clinging about the foot of Diamond Head, past the city itself, westward, until the misty green of cane fields carries it insensibly into the still more misty, pale-bluish purple of the distant Waianae Mountains.

Back of the city, to right and left, stretches the Koolau range of mountains, not very high (3,105 feet is the highest), but seeming higher than is the case because toward the top they rise sharply; because there is the space of a few miles only from sea level to their crests; because the quality of the atmosphere and the clouds that hover almost always over and above their summits give them that crystal blue which the mind naturally associates with far vistas of lofty peaks. It is on the slopes of these mountains that one finds the hot exaggeration of tropical colour—the yellow splotches that are kukui trees, the grey of fern masses, the emerald of ohia and banana trees, made more brilliant through contrast with dashes of brick red earth.

The picture is never for two days the same. Sometimes there is an opalescent mist that is not really mist, but rather a denser atmosphere which fuses the colours. Occasionally the clouds hang sullenly over the mountains and the water along the shore is black, with streaks of pale green. Another day the trade wind is blowing—and this is true three-quarters of the time—the air sparkles, the mountains shine against a sky clean swept except where the great, lazy, cream-white and pearl-grey clouds, gathering somewhere beyond the hills, pile through the gaps and then make veils of sudden showers high in the valleys, or, sailing onward toward the south, disintegrate and disappear. The traveler knows the approach to San Francisco, to Southampton, to Madeira. The first view of Honolulu, as the steamer rounds Diamond Head, is in its own way quite equal to these; remains always in memory as a vision, lovely and radiant and supremely satisfying.

The harbour of Honolulu is not large. The entrance is 35 feet deep and 400 feet wide; the inner harbour is 35 feet deep and 900 feet wide, but this width is being extended to 1,200 feet. The water is always still. Indeed, the name Honolulu means "the sheltered" and is appropriate, since there are few severe storms and no weather affects the safety of the harbour, which, in consequence, is usually crowded with shipping. As the steamer enters the channel people watch the Japanese and Hawaiian fishing boats, usually dories painted some bright colour, that contrast with the grey tenders of the men-of-war. Near the dock the water is alive with Hawaiian boys swimming about and shouting, ready to dive for nickels and dimes, not one of which do they miss. They are marvellously dexterous swimmers and give incoming passengers amusement that is pleasanter and more unusual than looking at the undoubtedly practical but also undoubtedly ugly warehouses and United States Government storehouses which line the shore. Not much more attractive in looks is the nearby quarantine station. This, however, is an excellent modern station under Federal control and is capable of caring for SO sick people, 100 first cabin and 300 second cabin passengers, 600 immigrants, and 1,600 troops. Nor is the dock more suggestive of an exotic tropical city. White linen suits on the men, sometimes the sickly smell of sugar, always Hawaiian women with wreaths— "leis" they are called—of flowers to sell, at least make one realise, however, that one is not landing in a northern port. The piles of coal, the dust, the hurry are alike in all ports where commerce is of more importance than is the sensation-hunting tourist.

Nor is the first glimpse of the city more reassuring. Indeed it may as well be admitted that Honolulu is, architecturally, very bad; that in the business portion, where vines and trees do not hide, the ugliness is sometimes depressing. There are fine modern business blocks, as completely fireproof and as completely uninspired as any in Chicago. Next to them may be low, shoddy wood or brick buildings. Some of the newer buildings, and especially, let it thankfully be said, public buildings, such as the fire station, built of blue-grey Hawaiian stone, would be pleasant to look at anywhere, but in general the business part of the city is in that sad intermediate state which is neither trimly new nor picturesquely old. It pleases only those who live there, and then not aesthetically, but as its growth indicates material progress. This accusation of commonplaceness is true only, however, when one takes the city as a whole. Single glimpses are often wonderfully attractive—the fish market with its piles of gaudy fish, every colour of the rainbow, the different booths presided over by Hawaiians or Orientals; the sidewalk on Hotel Street, lined with Hawaiian flower-sellers with their basketfuls of cut flowers and their leis of every colour, laid in rows on the sidewalk; or some queer comer giving a vista up the Nuuanu stream; or some little wooden house lost under a great mass of bougainvillea. These, fortunately, are the things which one never forgets. In a month the commonplaceness is gone, but the beauty and the strangeness remain.

Honolulu, a city of about 50,000 inhabitants, stretches for several miles on the narrow plain between sea and mountains, reaches up into the valleys, and sometimes actually climbs the steep hillsides. The most thickly settled portion is on the slopes of Punch Bowl—so named from the shape of its crater—a comparatively recent cone, 500 feet high, thrown up by some expiring volcanic action between the spurs of the mountains and the ocean. At its base, a little to the westward, lies the business portion of the city; huddled on its higher slopes is the Portuguese settlement; to the east, as far as the suburb of Waikiki, and to the west, in the mouth of Nuuanu Valley and beyond in parts of the Palama region, are the houses of the better class of citizens. One who intends to stay more than a day or two in Honolulu should drive as soon as possible to the top of this hill, because from here one can get the best idea of the topography of city and surrounding country.

The streets, in so far as the uneven character of the land permits, are laid out at right angles. Fort Street and Nuuanu Avenue running from the sea toward the mountains, and King, Hotel, and Beretania Streets, more or less parallel to the coast, give, as being the principal thoroughfares, sufficient indication of the street plan. All, after leaving the business centre, pass between luxuriant gardens, which are never shut in by walls, but are enclosed only by low hedges, usually of red flowering hibiscus. In many parts of the city the streets are bordered with tropical flowering trees that are a glory in the late spring months. An admirable electric car service covers the entire district of Honolulu, traversing or crossing all the main streets.

This car service, which makes distance unimportant, makes also less important the situation of the hotel chosen by the tourist. In the city proper the Young Hotel, a modem stone building, and the Royal Hawaiian, standing in its own little tropical garden, are the best. There are good hotels also at Waikiki, and these, with the Pleasanton, near the mouth of Manoa Valley, are to be recommended for a prolonged stay. The Pleasanton, a residence that has been converted into a hotel, is surrounded by large and really beautiful grounds.

Of public buildings the first in importance is the Executive Building, formerly the Royal Palace. This stands near the centre of the city, on King Street, in its own open park. It is used now as the offices of the Governor and of Territorial officials and contains also the chambers of the Senate and House of Representatives. Built in 1880 of blocks of concrete, much over-ornamented, to suit the King's ideas of beauty, it follows no recognised style of architecture, would be in any northern city amazingly ugly, but standing alone as it does, with no other buildings as contrast, approached on all four sides by short avenues of superb royal palms, surrounded by splendid great trees and gay shrubs, cream-coloured, its wide, cool galleries giving an effect of lightness, it has an appropriateness that makes it almost beautiful. It is best on public holidays, when flags and bunting, flowers and brightly dressed women give the effect of gaiety that it so often had years ago when the King held public receptions or entertained his friends at native feasts. One could never take the little Court quite seriously and the impermanent "World's Fair" quality of the building that so suited the playing at royalty and that still suits the sunshine of the tropics, makes it less suitable as the theatre of legislative squabbles and as the source of heavily serious gubernatorial messages. It was as the palace of a king, unimportant in the world's sight but immensely important in his own, that the building's outward purport was best fulfilled. The interior has dignity. The entrance hall, with its portraits of kings and queens and princes, is simple and stately^ as is the excellently proportioned Chamber of Representatives, formerly the throne-room, at the right of the hall. The dining-room, reception rooms, and bedrooms have been changed beyond recognition in being remodelled to suit office needs. Around this building centres much of the later history of the Islands. It was the scene of the insurrection of 1889. On its steps the body of King Kalakaua, brought home from San Francisco, was met by the Queen Dowager and the new Queen, Liliuokalani. Here, in January, 1893, the Queen, after dissolving the legislature, let it be known that she was about to promulgate a new constitution—the fact which was the immediate cause of the revolution that resulted in the establishment of the Republic. Here, in her old throne room, in 1895, the Queen was tried for treason. Here to-day the Territorial laws are enacted.

Opposite the Executive Building stands the Court House, formerly the Government Building, where the legislature of the Kingdom held its sessions. The Court House is a long, two-story building, its two wings connected by verandas lined with Ionic columns. In front, among the palm trees, stands the statue of Kamehameha I, a spear in his hand, the cloak of royal yellow feathers over his shoulder, and a helmet of feathers on his head. The original bronze, of which this is a replica, was lost at sea, but years later was recovered and sold to the Hawaiian Government. It now appropriately stands in Kohala, on the Island of Hawaii, the last home of the great King. These two, the Executive Building and the Court House, make the official centre of the city, and, with their surroundings, it would be fair to say the picturesque centre as well.

A few steps to the east stands Kawaiahao Church, with the mausoleum of King Lunalilo beside it. This church is the impressive monument of the early missionary labour. It was dedicated in 1842 and was the royal chapel until the coming of the English Mission twenty years later. Built of blocks of coral, it is in shape a rectangle. Over the main entrance is a low, square tower, which used to have an inappropriate wooden spire. White, surrounded with huge algaroba trees, through the filmy leaves of which perpetual sunlight plays, it typifies in its Puritanic dignity and rigorous simplicity the lasting work of its founders. Behind it, in a cemetery as unpretentious as they were themselves, most of these founders are buried. Beyond, in the section of the town formerly known as the Mission, what remain of their houses are clustered. One of these, the Cooke homestead, which was the first frame house built in the Islands, is now a missionary museum. The Castle homestead, greatly enlarged from the original, one-story plaster cottage, is now used by the Y. W. C. A. Whatever one may think of missionary work in general, whatever absurd tales one may hear of the self-seeking of these particular missionaries, the imagination and the heart must be touched by this plain old church and these pathetic little old houses where, nearly a hundred years ago, a band of devoted men and women, desperately poor, separated by six months from home and friends, gave up their lives to what they believed was God's work. That their children and their grandchildren chose, most of them, to remain in this land of their birth and to enter secular life; that they have largely guided politics and business, has been a lasting blessing to the Islands. Their presence only has made the people capable of becoming normally and naturally American citizens.

Kawaiahao, which still has the largest Hawaiian congregation in the Islands, and where the services are still conducted in the Hawaiian language, is the only church in Honolulu built in a style characteristic of the tropics, a style which should be equally characteristic of Honolulu. Central Union (corner Beretania and Richards Streets), a non-sectarian church, the place of worship of most of the descendants of the missionaries, and the strongest numerically and financially in the city, is built of grey-blue native stone, but is architecturally characteristic of a New England town during the period, about twenty or thirty years ago, when buildings were most unprepossessing. St. Andrew's Cathedral (Emma Street), formerly the property of the Church of England and the seat of an English bishop, who was Royal Chaplain, now under a bishop of the American Episcopal Church, is a simple and beautiful building in a style which people are pleased to call Victorian Gothic. The Roman Catholic Cathedral (Fort Street) is a plain, square stone building, which is rapidly being ruined in appearance by the application on the outside of what is believed to be Gothic ornamentation. Like all small American cities, Honolulu has, too, meeting-houses representing most of the normal and abnormal of the Christian denominations. With one or two exceptions these buildings are unsubstantial and hideous, but are fortunately inconspicuous.

The excellent school system of the city is appropriately housed. The public grammar and high school buildings, most of them comparatively new, are built according to approved methods of school-house construction, and in their outward appearance suggest a hopeful reaction in the direction of suitable architecture. They are long, low, and cool-looking, in a style adapted from the Spanish, which is admirably suited to the surroundings. One older school is established in the Bishop homestead on Emma Street, the house where Mrs. Bishop, the last of the royal line of Kamehameha, died in 1884. It has not been changed and still looks like an expensive private house of forty years ago, but is worth a visit because of its historic associations and because of the beauty of its grounds. A little further up the same street, opposite the gloriously tropical gardens of Judge Dole, are the plain wooden buildings of the old royal school where formerly the chiefs were educated.

Mrs. Bishop, who was the finest type of Hawaiian woman, refused the throne to which she was heir and at her death left her large property for educational purposes. It has been used in building the Kamehameha School for Hawaiians, situated about two miles west of the city. Mr. Bishop, a man of power, charm, and loyalty, has supplemented her gift by adding to the school equipment a biological laboratory, by generous endowment, and by building the great Museum. Kamehameha is a semi-military school, with a membership of about 250 Hawaiian and partly Hawaiian boys. Across the street from the boys' school is situated a girls' school, with about 125 pupils. The large group of buildings of native stone, the walls covered with vines, would compare favourably with the buildings of any American school, and in their setting of trees, with the nearby mountains as a background, are unique. Here the boys are taught trades as well as elementary subjects. To see them marching to chapel in the morning, neat and manly in their grey uniforms, to watch them working at their desks or in the lathe or forge shops, or playing football on the campus, makes one understand why it is that the school turns out the most useful class of native citizens.

Another school or group of schools primarily for Hawaiians is the Mid-Pacific Institute, situated in Manoa Valley. The best known of this group is the Kawaiahao Seminary, now established in a large building of rough stone in a high, cool site, which is in every way preferable to the old situation an King Street, near Kawaiahao Church. This school was started by the missionaries and has educated many of the best Hawaiian women. Another school in this group is the Mills Institute, established about twenty-five years ago by Mr. F. W. Damon for the education of Chinese and Japanese youth. It has now broadened its scope to cover other nationalities. The Mid-Pacific Institute, which represents work of a semi-missionary character, occupies about 75 acres of land, and will probably establish other schools for the study of theology and mission work.

Only one other school need be mentioned, Oahu College, or, as it is familiarly called, Punahou, situated on Punahou Street, at the mouth of Manoa Valley. The city has grown out and surrounded it now, but when the school was started by the missionaries for the education of their children and the children of other foreigners in the Islands it was well out in the country. At Punahou most of the girls and boys who go to American colleges are prepared. It sends every year students to Harvard, Yale, the University of California, and elsewhere. The school has well-equipped buildings in a park of 90 acres. The great algaroba trees at the entrance are the finest in Honolulu; there are beautiful avenues of royal palms; a pond of wonderful pink and blue water lilies; orchards of various tropical fruits; and all this in one of the coolest situations near the city. On the hill back is the splendid athletic field where most of the football and baseball games of the city are played, a spot where spectators can look from the game over the plains to the sea and to Diamond Head.

A building of real interest, constructed of brown tufa stone from Punch Bowl and surrounded by striking gardens, is Lunalilo House. This was established by bequest of King Lunalilo as a home for aged and indigent Hawaiians, and here about a hundred of them live on and on. Some are blind; some deaf; all are decrepit. They sit in the sun under the palm trees and talk of times seventy years ago, quarrel happily and vociferously, and sometimes marry—these octogenarians and nonogenarians. They have plenty to eat, comfortable quarters, a weekly excursion to church in an omnibus, and, life having become something nearly approximate to Heaven, they see no valid reason for changing their state. Not seldom do they pass the century mark and many remember, or claim to remember, the death of the first Kamehameha.

Another monument to the generosity of a sovereign is the Queen's Hospital, near the centre of the city. In 1859, by large donations and by personal solicitation of Kamehameha IV and Queen Emma, the money for this institution was raised. It is well worth a visit on account of the beauty of its grounds, which are almost a jungle of tropical growth and contain many uncommon plants. The winding avenue of date palms could not be surpassed, and directly behind the palms are masses of most luxuriant and often sweet-smelling vegetation. If one could only look out from the jungle on wastes of golden sand instead of on busy streets it would be easy to imagine oneself in Count Landon's garden in Biskra.

There are in Honolulu two public collections of the highest importance and interest, the Bishop Museum at Kamehameha School and the Aquarium at Waikiki. The Museum, covering all aspects of the islands of the Pacific, zoological, geographical, ethnological, and historical, has become, under the able management of Mr. William T. Brigham, one of the great world museums. Its collections, which are admirably arranged, are of incomparable value to the student of science, and—which is not always the case—are keenly interesting to the layman. Here one sees the ancient royal regalia, superb yellow feather cloaks and helmets, as well as kahilis, the great feather standards of every colour, which were the insignia of rank. These regalia, which had been inherited by Mrs. Bishop, formed the nucleus of the Museum collections. Passing from the room where these are, one sees weapons of all kinds; implements of stone and of wood and of bone; life-sized groups illustrating the tenacious but nevertheless passing customs of the Hawaiians, as well as the life of other Pacific islands; innumerable birds, many of them extinct; land-shells with their exquisite colouring; specimens of flora and of fauna. The Museum is distinctly divided into a Hawaiian and a Polynesian section, but the collections are being so rapidly augmented and are so often changed that no guide can be given. There are attendants to show people about and there are handbooks. The Museum is open daily, except Sunday, and ought not to be omitted by any one who is visiting Honolulu. In its more limited way, the Aquarium at Waikiki —open every day—is of equal interest. It is said to be second in importance to the aquarium at Naples, but certainly far surpasses it in the beauty of its collection. The fish are indescribably beautiful, and some of them—which is one of the delights of an aquarium—are indescribably funny in their actions and in their expressions. And the queer Hawaiian names also are sometimes amusing. One queer little fish, for example, is named the Humuhumunukunukuapuaa. The brilliance of their colours, the extraordinary blending and striping and spotting, seemingly impossible in their combinations, yet always resulting in harmony, might well be the life study of an artist, whether sane or "futuriste." One feels that these fish have absorbed all the vivid colours of the sunshot tropical sea which was their home.

The Aquarium is at the edge of Kapi`olani Park. Here there are charming drives and walks along palm-lined avenues, between canals and ponds filled with red and white and blue and pink water lilies or with masses of the pale lavender water hyacinth, across rustic bridges to little islands dotted with fan palms, between masses of brilliant-leaved crotons or of hibiscus or of oleanders. And always through the trees there are glimpses of the distant blue mountains, always, when the wind is at rest, there is the murmur of the sea. The park covers about 125 acres, and with proper financial support could be made one of the loveliest gardens in existence. As it is, it looks and is unkempt; many of the plants are allowed to spread too much and are not properly cared for, but no lack of care can destroy the colour of the flowers nor the charm of the frame. The city controls other smaller parks, but in the tropics, where every house, however humble, has its garden, there is not the imperative need for breathing space that there is in most cities, and as down-town parks Thomas Square, of five or six acres, and Emma Square, of hardly more than an acre, serve as public gardens and places for band concerts. The other public parks are laid out, therefore, primarily as playgrounds and athletic fields.

Private gardens line all the streets, their luxuriant trees and shrubbery happily masking the houses themselves, most of which make no pretense to anything but comfort. People live out of doors, and the result is that broad vine-covered verandas or " lanais "—the Hawaiian term is used universally —are the most noticeable and characteristic features of many of the houses. The glory of the gardens is their palms—royal palms and dates principally, but also wine palms and fan palms— and their flowering trees. In the spring the Poinciana regia makes huge flaming umbrellas of orange or scarlet or crimson; the Golden Shower, sometimes a stately tree, is hung with its thousands of loose clusters of yellow bells; the Cacia nodessa spreads its great sheaves of shell-pink and white blossoms like a glorified apple-tree; the Pride of India is a mist of lavender. But at all times of the year these trees look well, and in addition to them there are gigantic banyans throwing cool purple masses of shade; algarobas with their feathery leaves through which the sunlight is pleasantly diluted and the insignificant flowers of which supply the tons of honey exported annually to England. Near the coast the ancient indigenous hao, half-tree, half-creeper, builds natural summerhouses. So thickly does this tree grow that there is fantastic truth in Mark Twain's statement that when the hao is massed at the foot of a low cliff cattle walk from the cliff brink into its topmost branches and roost comfortably, like hens. Nor is there altogether falsehood in his other statement that the cocoanut-trees which fringe Hawaiian shores look like feather-dusters struck by lightning. They do, and yet no tree is more stately than this slender spire, crowned high in the air with its cluster of graceful leaves. Stories of monkeys throwing down the nuts are only untrue because there are no monkeys. The Hawaiians, however, run up the trees almost as monkeys would to gather the fruit. The vines in Honolulu are no less striking than are the flowering trees and are in bloom more continuously. Bougainvillea, magenta or brick-red or cherry colour, grows to the tops of the highest trees and makes mounds of colour over many an unsightly barn; the bignonia grows as an impenetrable curtain of brilliant orange; there are walls of purple or yellow alamander; the " yellow vine," another bignonia, climbing high into the trees, drops its long, restless fringes of lemon-yellow flowers; the less common beaumontia holds up its pearl-white cups, pencilled with pink on the outside, each as large as a teacup. Other less noticeable vines, such as the ivory stephanotis and ylang-ylang, make the air about them heavy with their sweetness. And beneath all these the shrubs add still other colours. The hibiscus is cultivated as nowhere else, many working over it as the Dutch work over their tulips. The commonest form is the single scarlet, but there are single pink and white and yellow flowers, and others cut like coral and of the shade of coral. There are double ones, too, of pale chrome or vivid gold, or of pink, and white, and crimson like finest peonies. There are shrubs of all descriptions with coloured foliage; there are plumarias of white or orange-yellow growing out of bare branches that look like cactus; there are oleanders of all colours, and poinsettias that grow to the size of small trees. The stone wall around two sides of Oahu College is covered thickly with night-blooming cereus, and the spectacle on a moonlight night when thousands of the great white flowers are open at once is indescribably beautiful. Only the normal garden flowers are rare, and this not through any fault of soil or climate—Honolulu used to rival California in its roses—but because of plant pests that have been introduced from Japan and the American continent. These are gradually being controlled, and within a few years every Honolulu garden will again be a garden of roses. Still, there are asters the year round, carnations by the million, most of the annuals, gladioli, and lilies, so one is not at a loss to find flowers for the house.

Perhaps the best of these private gardens are those along Nuuanu Avenue, which was settle dearly, and those in the vicinity of Oahu College, although this general division does not mean that there are not good gardens in all parts of the city. One of the most satisfactory places, from the picturesque point of view, is Washington Place, the home of the Queen, near the Hawaiian Hotel. It surpasses most because the house is as good as the garden, and both express the tropics. The house has wide lanais, supported by high white columns, something in the Southern colonial style, and is simple and dignified. Around it are great trees that shut away the street, that keep the house always cool. The whole has an air of retirement expressive of the attitude of the Queen herself.

There are everywhere beautiful single gardens, stately avenues of royal palms, masses of colour, but what the visitor carries away as something which can never be forgotten is not the impression so much of any single spot as of the whole; of one great garden where many men have built their habitations—a garden in an amphitheatre of glorious mountains over which march columns of clouds that gleam white against the blue of the sky; a garden looking out over a shining, tropical ocean, peaceful, happy in the sunshine; an oasis, small but perfect, in the immense desert of the Pacific. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |