Hawai`i Past and

Present

By WILLIAM R. CASTLE, JR.

New York—Dodd,

Mead and Company 1913

|

CHAPTER 7

Oahu

The Island of Oahu, halfway between Kauai and Maui, contains 598 square miles and is the third in size of the group. The shore line is extremely irregular and the Island, therefore, has more harbours than any of the others. The low coastal plains are usually uplifted coral reefs and there is also much growing coral around the Island. There are two mountain ranges, one running the length of the Island from northwest to southeast, the other forming the southwestern portion. These ranges, very differently affected by erosion, give varied scenery. Honolulu, the only important town, is the natural centre for excursions, most of which can be made in half a day or a day by carriage or by automobile.*

First to be seen are some of the many valleys cutting the leeward slope of the principal mountain range, valleys of infinite variety, and all beautiful. Of these the most accessible and thoroughly characteristic are Manoa, the first valley to the east, and Nuuanu, back of the city. Manoa is very broad, with an undulating floor running back to the base of the mountains, which rise abruptly. Konahuanui (3,105 feet), at the left, is the highest peak of the range, and Olympus— unfortunate misnomer—at the right, appears only a little lower. From the mountains long ridges descend gently to the plain, the sides of the valley, however, being steep and rocky. The lower part of Manoa, which is reached by the electric cars, is being rapidly built over, but beyond the houses are taro patches, groves of banana, masses of wild guava, and jungles of lantana. Nothing could be more serenely lovely than the semicircle of mountains, the green of all tints—^yellow of kukui, neutral of lehua and ferns, and emerald of ohia— shading into blue as the hills rise higher. The trade wind clouds drifting across the summits disperse in misty showers that keep the valley always fresh and yet hardly obscure the sunlight.

Very different is Nuuanu Valley. This is a narrow cut through the mountains, affording the only route, except that around the coast, to the windward side of the Island. An excellent road winds up the valley; after it leaves the lower, inhabited part, between fields of long grass that ripple in the wind like waves, between lines of tropical trees and rocks overgrown by vines. Behind there is always the ocean and on either side, and ahead. the mountains, apparently blocking the way. After a rain hundreds of miniature waterfalls spray over the sides of the valley, only to be blown away before reaching the bottom. Quite suddenly, about six miles from the city, one reaches the Pali, the precipice 1,600 feet high, over which the conqueror Kamehameha drove the army of the King of Oahu. On turning a sharp corner the south side of the Island is gone and one looks down on the windward coast. It is one of the most unexpected and amazingly beautiful views in the world. The narrow northern coastal plain is buttressed on one side by the abrupt precipitous mass I of mountains, and on the other is washed by the sea. Little islands along the shore break the even surface of the water. The plain is dark with wild guava bushes, or tinted by the yellow-green of cane fields, or checkered with the grey of pineapples, or cut with great red gashes where the earth is exposed. The mountains reach on and on, it first bare, bleak precipices, then torn into sombre gorges, deep purple-blue, forbidding and fascinating. One looks and looks, and the colours shift, and the islets glow more brightly or are blurred for an instant in a sudden spray of rain, and the sea changes ceaselessly like a great opal, and the surf makes white, waving fringes on the yellow sand. Gradually one becomes conscious that the road, which seemed suddenly to end, continues down the mountains, cut in tortuous line around the precipices. And then one inevitably goes on a little further in order to look back and so to get the full, overwhelming impression of the towering cliffs. Little mountains these are, when compared to the Alps, and yet in all Switzerland there is no view more wonderful, more varied, more memorable than this, because there is no view that more stirs the imagination. Later, when the scene has become a memory, one asks oneself why this is, and the answer is, perhaps, the Sea. The far, naked horizon, the tireless surge of the waters, the consciousness that for four thousand miles to the north and to the west there is nothing but this endless, breathing ocean—the power of it; and against this seemingly resistless force only the ragged volcanic mountains of a lonely island, breasting winds and waves. There is something to inspire in the thought. And then, if it was afternoon, the sun shot golden spears of light through the clouds over the western mountains, making the plain between the dark gorges and the sea all radiant, and the gold glimmered on the waves. So later one can realise that, after all, it is not the conflict, but the harmony of these elemental forces that is so impressive.

No view in Oahu is as spectacularly beautiful, as stirring, as that sudden vision from the Pali. Others are as lovely, more peaceful, perhaps more permanently satisfying. Pre-eminent among these is the prospect from Mt. Tantalus, back of Honolulu, where people are beginning to build summer cottages. From behind Punch Bowl the road (not open to automobiles) winds upward along the lower ridges, which have been reforested with eucalyptus, Australian wattle, and other trees, skirts the last steep cone of the mountain, and loses itself in the native forest, almost a jungle, that covers a maze of tiny valleys and old volcanic cones. From the slopes of Tantalus one gets the whole sweep of ocean from Diamond Head, and beyond, to Barber's Point, the southern end of the Island. Just below. Punch Bowl holds up its empty crater. West and east from the city stretch the undulating plains with their diversity of vegetation. Far to the right is the silver line of Pearl Harbour, and beyond it the faint blue mass of the Waianae Mountains. Through trees on the nearer ridges Diamond Head stands out, yellow-brown against the metallic blue of the sea. From almost everywhere one sees it—this hill guarding the eastern approach—low, long, and kindly, dignified as an ancient, titanic lion asleep, its forepaws washed by the waves. One grows to love it and to look for it as the key-note and index of every view. At the Pali an hour at a time is enough. It is a framed picture, clear-cut and masterly in the drawing, exciting to the imagination, but finally almost tiring in its perfection. The view from Tantalus has no frame except the horizon. One looks away from the mountains but feels them as a background. There is always something new to be discovered in the picture. There is a serenity about it that is infinitely restful. Jean Jacques Rousseau would have sobbed violently and loudly at the Pali. On Tantalus he would have smiled, if he knew how to smile, or if tears were his inevitable method of expression, they would at least have been silent, happy tears.

There are many drives or automobile trips to be made near Honolulu. One, passing through Waikiki, follows the corniche road around Diamond Head, to Waialae, with its excellent school for boys who cannot afford the tuition fee at Punahou, its wild and beautiful valley (only to be reached on horseback), and its great cocoanut groves; then back through the new residence district of Kaimuki. Good roads lead into some of the valleys and to the new residence sections on the heights to the west and the east of the city. A delightful drive is westward to Moanalua, with its queer little twin craters, one half-filled by a salt lake, its rice fields, its excellent polo ground, and its gardens, one of which, that of Mr. S. M. Damon, is large, admirably laid out, and well kept, and IS often open to the public, as are the great private gardens of Italy.

The railway that will eventually make the circuit of the Island, after leaving Honolulu, passes through Moanalua, cuts across the cane fields of the Honolulu Plantation, makes almost the circuit of Pearl Harbour, passes Oahu and Ewa Plantations, rounds Barber's Point, and, from Waianae, follows the western shore of the Island through Waialua to Kahuku, the northwestern point, and then, turning eastward, ends about ten miles beyond the point. From the windows of the train (the left-hand side is best) one gets as good an idea of this part of the Island as can be obtained on a three-hour railroad trip. A few miles from Honolulu one reaches Pearl Harbour, with its ten or more square miles of deep water, perhaps the finest land-locked harbour in the world. Its shores are low, deeply indented, sloping gradually upward at the north and west. In places the cane fields extend to the very edge of the water. In places there are bits of almost barren plain where only lantana grows—the pest of the Islands, that on the mainland is so tenderly cultivated in many a garden for the sake of its pretty mauve and pink or white and scarlet flowers. In the harbour are low islands, bare, or spotted with trees and occasional houses. On the flat eastern banks are the government buildings, barracks and shops, and the great drydock. On the Peninsula, in the western part of the harbour, is a colony of summer cottages, each with its trees and garden, where many Honolulu people go for week-ends to enjoy the excellent bathing and boating. Nothing could be prettier than the view from here, across the still water, dotted with sailboats and canoes and, now that the dredging of the entrance has been finished, bearing great grey battleships and cruisers; across the water to the cloud-capped mountains beyond the cane fields, and far to the eastward Diamond Head, distant but still beautiful, jutting into the sea.

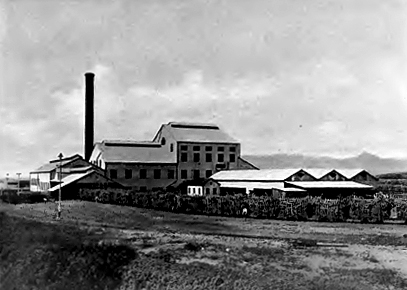

From Pearl Harbour the train cuts across the broad cane fields of the Ewa Plantation, fields that in the flowering season are a sea of waving pale violet plumes, like feathery pampas flowers. The huge mill and pumping stations of the plantation may be visited. Beyond, on the barren plains that slope upward to the Waianae Mountains, there are fields of sisal, each plant looking like a rosette of spears protruding from the ground. Through scrub algaroba forests, where honey bees are raised, the railroad passes around the southern end of the Island to a very narrow plain, sometimes hardly more than a causeway between mountains and ocean, and across the mouths of broad valleys which run deep into the heart of the range. In these valleys is grown most of the cane of the Waianae Plantation. At the end of the mountains, on the western sea, is Waialua, a pretty little village between the two ranges, where, on the beach, a delightful hotel serves good luncheons and provides clean, comfortable quarters for those who can stay a few days to enjoy the splendid surf bathing or to go goat or wild turkey shooting in the mountains. The view of Kaala, with its surrounding peaks and gorges, is very good from the beach in front of Haleiwa Hotel. The Waialua Plantation is large and is, for Oahu, unusually picturesque on account of the hills and ravines over which the cane grows. The ditch which carries water from the mountains, and the reservoir supplying it, are an interesting piece of engineering work.

Beyond Waialua, again along the narrow seaboard, the surf dashes almost to the windows of the cars. The mountains, not so high, are more mugged and barren. Over the rocks in one place, however, one catches a glimpse of the tops of rubber trees, part of a young plantation. Along the rocky shore Hawaiian fishermen are often seen, bronze in colour, dressed only in the ancient loin cloth, casting their nets into the waves. They come probably from Waimea, where, in a valley a few miles beyond Waialua, is one of the few remaining primitive Hawaiian settlements. In this valley two members of Vancouver's party, Lieutenant Hargest and Mr. Gooch, an astronomer, were murdered. Their ship had stopped for water and the two had wandered inland to explore the country. It was at a time (1792) when the Hawaiians were particularly bitter against foreigners. The little valley, with its ruined temple and its grass houses, is more typical of Hawaii before 1800 than anything in the Island. The air grows cooler as the hills recede, the breeze fresher, until, at the north point of the Island, there is a steady, strong wind blowing in across the ocean from the northeast, a wind full of life, a sea wind, purer than any other. It tatters the leaves of the cane on the Kahuku Plantation, but does not hurt the cane itself, and the moisture of it brings out all the colours in trees and flowers. The manager of the plantation is a New England man, and back of his house are masses of wonderful hollyhocks, almost the only ones on the Island.

The automobile road from Honolulu around the Island follows the line of the railroad to Kahuku, except from Pearl Harbour to Waialua, where, instead of following the coast, it crosses the plateau between the two mountain ranges. Here, at an altitude of about 1,000 feet, are stationed U. S. Cavalry and Infantry quarters, and at almost all hours of the day troops may be seen drilling on some part of the plain. On the other side of the road from the encampment are thousands of acres of pineapples, the fruit from which is sent to all parts of the world. Further on, the road climbs down and up again through grim, barren gorges that have been torn out by centuries of sudden rainstorms. The largest of these gulches is Kipapa, the scene of one of the bloodiest of ancient battles. Beyond the dam which holds back the water for the Waialua Plantation the road descends in long turns to the Haleiwa Hotel, and from here to Kahuku follows once more the line of the railroad.

The northern point of the Island marks the end of the first half of the one-day automobile trip of ninety miles around this part of the Island. It is, perhaps, the more varied, but certainly the less beautiful half of a trip that in European guidebooks would be double starred. Six miles beyond Kahuku the road passes Laie, the Mormon settlement. Several hundred Mormons live here, most of them Hawaiians, who raise sugar cane to be ground at the Kahuku mill, and who practise their religion more strictly in accord with the civil law than is reputed to be the case among the Mormons in Utah. The coast soon becomes narrower; the mountains rise more perpendicularly; the valleys are more like cañons. One of them, Kaliuaa, is so narrow that at the base of the waterfall at its southern end only a thin lozenge of sky is visible. A side excursion on foot to this valley is well worth the rough walk of about two miles. It is filled with ohia trees, which are often laden with their red, somewhat tasteless, but cool and refreshing fruit. Natives, on entering the gorge, always pick the large polished leaves of the ohia and lay them crossed on the ground as a charm to prevent rocks falling from the cliffs. The waterfall itself is thin and high, sliding in a groove down the solid rock. There is a legend to account for this groove that the demigod Kamapuaa, in trying to escape from a king who was chasing him for stealing chickens, fled into the valley and, reaching its precipitous end, dragged his canoe up the face of the rock, thus marking it forever.

The ocean on this northern side of the Island seems to be of a quite different character. Instead of a choppy sea, variegated in colour, as on the southern shore, it is an even, deep blue, and stately billows like those in mid-ocean roll in, to sweep noiselessly over the broad beaches of white sand. The hills press more and more closely to the water, except where the flat valley bottoms give space for the cultivation of rice and taro. Glimpses up these valleys reveal a more luxuriant vegetation than on the leeward slopes, because the mountains intercept much of the rainfall.

It is not until reaching Kualoa Point that one gets the most glorious view—the reverse of that seen from Nuuanu Pali. Kaneohe Bay, deep, protected by coral reefs, and dotted with islands, many of which are the peaks of submerged volcanic hills, lies straight ahead beyond another, shorter point. Between sea and mountains is a broken plain. There are no more valleys, the mountains rising like a continuous, blue, crenellated wall to beat back the wind and to catch the water in the clouds that drift in from sea. This wall of rock, which, beyond the Pali, reaches out into the sea at Mokapu Point, looks almost semicircular, and it is possible that instead of being the work of erosion only, it is the magnificent ruins of some stupendous ancient crater, the other half of which has sunk into the sea. The less spectacular theory, that it is the result of centuries of beating by wind and rain, may be true, but whatever the causes the final panorama is superb.

The road clings to the shore. The mountains grow more and more impressive, partly through contrast, as they are seen across the tender green of rice fields or the grey of pineapples, partly because they really become higher as one travels southeastward. More and more is the imagination stirred; more and more is there mystery in the blacker shadows that reach over the plain. One believes the Hawaiian legend that on a certain night of every year the conqueror Kamehameha marches with his ghostly army along the face of these hills and that all those who see the glimmer of the spears in the moonlight and who hear the trampling of the feet must surely die. At Ahuimanu—in English the "gathering place of birds"—there is an old house, at the end of a branch road leading for a couple of miles directly away from the shore. It was built by the first French Bishop of Honolulu as a place to which he might retire for meditation and prayer. It stands close to the foot of the precipices and is shadowed with aged trees. From its windows one looks up and up until the rocks are hidden in the clouds. They might reach the sky for all one knows, and one very soon gets to believe that they do. Only for a few hours does the sun reach this solitary farmhouse. The only sounds are the murmur of streams and the roar of the wind as it strikes the mountain wall. It is a sombre spot in a way, and yet there is an unworldly, almost superhuman fascination about it that somehow sets off this secluded corner of the Island as something quite apart from all the rest. It is shut in, a place in which to dream—the Bishop knew what he was doing when he built—whereas the southern slopes are full of sunshine in which are all the simple realities of life.

The road turns away from the sea at last, crosses a plain covered with pineapples and leads straight toward the precipice, which is no less abrupt here than elsewhere, though not so high. The ascent would seem impossible were it not that one can see the road—a line twisting and turning around the rough face of the rocks. And a good road it proves to be, in spite of the hairpin turns, which in late years have been eliminated as much as is humanly possible. As one ascends the view grows broader, less detailed, more full of blending colours. The wind roars through the gap above. A long curve around the face of the cliff that juts out from the main range, rocks rising perpendicularly at the left of the road and at the right descending in a sheer drop of several hundred feet, one last look over blue ocean, variegated plain, and dark blue mountains, and then suddenly through the gap with the wind and before one lies peaceful Nuuanu Valley, descending gently to the city and the southern sea. In an instant the whole character of the scene has changed. It is no longer grand, but lovely; black mountain shadows are left behind, and before are sunshine and waving yellow grasses. No one since Dr. Johnson, with his definition of mountains as "considerable protuberances," could make the circuit of Oahu without enthusiasm, and even Dr. Johnson, though he pretended to despise, had a habit of seeking out wild scenery in which to spend his holidays. No motor excursion of a hundred miles covers more varied or more beautiful country than does this.

The trip around the shorter, southeastern end of the Island can only be made as a whole on horseback, since the Waimanalo Pali at the eastern point has only a trail across it. It is an interesting drive, however, along the shore eastward from Honolulu. Beyond Diamond Head is the wide, sandy plain of Waialae, with its algaroba trees and its cocoanuts; back of it deep valleys cut into the mountains. Beyond, at Niu, which is the last of the fertile valleys, there are interesting ancient burial caves easily reached from the road by a five minutes' scramble up the ridge. Koko Head, like Diamond Head and Punch Bowl, an old mud volcano, here juts into the ocean. From it, unless the day is misty, one gets a good view of the Island of Molokai across the channel, of the little Island of Lanai, with the higher mountains of west Maui between. Koko Head itself is absolutely barren, as is the land beyond it, a mass of rocks and lava make a tremendous fight for liberty. Very few of them are man-eaters, but the possibility of only one makes a man as cautious about swimming in an unprotected bay like this as the presence of a single man-eating tiger would make him cautious about wandering through the woods at night. Fortunately the shark hates shallow water, since in it he must turn over, either to attack or to defend himself, and the result is that no sharks cross the coral reefs which protect many parts of the Islands. Swimming at Waikiki and at other bathing resorts is, therefore, as safe as swimming in Y. M. C. A. pools. A story widely believed that sharks attack only white men, avoiding the dark-skinned natives, is false. The natives certainly are less easily seen in the water, and the legend may have arisen from the fact that the Hawaiians are fearless. They are marvellous swimmers and will sometimes dive under a shark and stab it in the belly, the only vulnerable part. The fact remains, however, as has been sadly proved more than once, that if a man-eater happens to see a Hawaiian who has got too far away from his canoe no agility can save him.

Beyond Koko Head a new carriage road winds upward over the wild desolation of rocks to the hill above the great lighthouse at Makapuu Point, at the extreme eastern end of the Island. From here the roughest kind of trail leads down the sand. Just under Koko Head to the east is a wonderful little horseshoe-shaped bay, very deep and often very rough, as the waves from the channel sweep through its narrow mouth. This is a favourite goal for the exciting sport of shark fishing. The sharks are caught with spears attached to heavy cord and, after being speared, Waimanalo Pali, directly over the water. Soon after reaching the bottom of the cliffs the trail strikes another carriage road that winds over a beautiful rolling seaboard and then, avoiding the cape which marks the eastern boundary of the great Koolau half-basin, it strikes back through the hills to the foot of Nuuanu Pali. This trip is a very short one as compared to that around the northern end of the Island—thirty miles as against nearly a hundred—but takes as long on account of the difficult pass. It is perhaps as beautiful, but is somewhat a repetition of the other trip, except for the barren plains beyond Koko Head. The trip to Waimanalo may best be taken as a side trip from the foot of Nuuanu Pali, and the excursion to the lighthouse and back to Honolulu made on a separate day, thus avoiding the really dangerous trail at Makapuu Point.

For those able to take rough walks Oahu offers innumerable opportunities. First and easiest, because of the good trails, are the many tramps that can be taken in the vicinity of Mt. Tantalus, back of Honolulu. An excellent trail branches to the left from the Tantalus Road just behind Punch Bowl. It follows the right-hand ridge of Pauoa, a shallow valley that extends only two or three miles into the mountains. Across the valley, on the western ridge, is Pacific Heights, a recently formed residence section, reached by electric cars. The bottom of the valley is lovely to look down upon, with its kitchen gardens and its bright green taro patches, the whole terraced and laid out in rectangles. The trail winds along the face of the ridge, now in the open, now through bits of forest; drops a little to cross the marshy plateau, overgrown with guavas, at the head of the valley; turns to the left, climbs again for a short distance, and comes out suddenly and unexpectedly over Nuuanu Valley, about two-thirds of the way from Honolulu to the Pali. Here there is an almost sheer drop of a thousand feet or more, which is, however, overgrown with trees and ferns and vines. The view of the valley is superb, and looking to the right one can see through the gap to the ocean on the other side of the Island. From here the trail turns toward the mountains again and continues northeastward, always overlooking Nuuanu Valley or the gorges that lead into it, and always winding its way upward through magnificent native forests. There are great kukui trees with leaves like the maple, but larger and cream coloured underneath; huge ferns that arch their fronds over the path; the ie-ie vine with its yellow candles surrounded by whorls of scarlet leaves; clumps of wild bananas; lehua trees with their flowers like pink flames; shrubs of mokihana, the berries and leaves of which are as sweet and as pungent as lavender. At last the path emerges from the forest on to a knife-like ridge that leads to the main mountain mass. Here one looks down a dizzy height into Nuuanu on one side, southward over the maze of hills back of Tantalus, and on the other side into Manoa Valley and the distant round crater of Diamond Head. Straight ahead is the peak of Konahuanui, a hard but safe climb of an hour, with no clearly defined trail. From Honolulu to the foot of the peak and back would take five to six hours. From here another path leads around the head of Manoa Valley to Olympus and so, with a stiff but wonderful climb, down the windward side of the range into Koolau. This, trip, returning by way of Nuuanu Pali, is a long day's tramp. Another trail branches off after passing the head of Manoa, and crossing a knife ridge—not safe for those unused to mountain climbing—leads into the head of Palolo Valley and to a queer little crater, overgrown with ferns, which seems lost in the mountains. From here this trail turns south and leads along the ridge to Kaimuki, a new residence section back of Diamond Head. The round trip takes about nine hours.

These are only a few of hundreds of invigorating walks, but are the only ones with well-defined trails. The mountains are public lands; there is little danger of getting lost or of running into serious difficulty, unless one actually attempts to cross the range. The only rule when in doubt as to the way home is to go toward the sea—in general southwestward—and always to keep on top of the ridges. This may mean an occasional long detour, but the valley bottoms are almost certain to have waterfalls which are quite impassable. It is always a temptation to go down into the valley, where the way looks easier, but it means invariably a very hard climb to get back again to the top of the ridge. Although the greatest altitude is only 4,000 feet, the peaks are steep, and many of them give real mountain work. On the main range these peaks are usually covered with ferns, vines, and tough shrubs, which make the climbing easier for the amateur, but not safer, because he is more careless. In the Waianae Range many of the points are of bare rock that is a test for the most expert. From the northeast side of the Island the precipices are inaccessible, except in a very few places, but from any point on the southern and western sides the crest of the range can be reached by walkers who are willing to fight their way through masses of undergrowth—an undertaking safe in almost no other tropical country. For the strong walker the field is, therefore, almost inexhaustible.

Aside from Honolulu itself, and the drives in its environs, there is one trip, that around the Island by automobile, which should not be missed by any one who visits the Territory. Omitting the walks, there is certainly enough to fill every moment of one's time for a week, but only those who stay longer and who are willing to go out of the beaten track can realise the full beauty of Oahu or understand its charm. |

||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links |