Hawai`i and Its Volcanoes

|

Hawaii and Its Volcanoes by Charles H. Hitchcock, LL.D. of Dartmouth College EARTH SCIENCES LIBRARY, COPYRIGHT, 1909 BY THE HAWAIIAN GAZETTE Co., LTD PART 2: The History of the Exploration of Mauna Loa CONTENTS:

Mauna Loa The First Known Attempt to Ascend Mauna Loa Mokuaweoweo Between 1832 And 1843 The Wilkes Party Upon Mauna Loa The Eruption of 1852, described in verse by Titus Coan Eruption of March, 1852, by J. Fuller

The

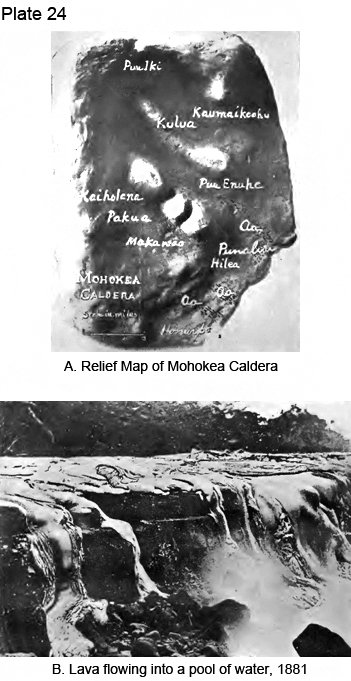

Eruption of 1859 Mokuaweoweo between 1868 and 1880 Visits of W. C. Merritt and E. P. Baker in 1888 Professor Ingall's Observations The Vents and Fissures Situated upon a Watershed Notes upon the Kahuku Lava Flow of 1907 Mohokea Compared with Haleakala Phases in the Development of Hawaiian Calderas Volcanic Ash of Hawaii and Its Source Order of Events in the History of Mohokea Eruptions of Lava from the Lower Levels This term is applied to an immense dome seventy-four by fifty three miles in its two diameters as measured at the sea level, and 13,650 feet in altitude. Its mass extends downwards more than 16,000 feet farther to the level of the submarine plain at the bottom of the sea upon which the whole Hawaiian Archipelago is situated. That would be a cone 30,000 feet in height and as much as a hundred miles wide within which are one or more conduits leading to the reservoir of lava which supplied the material for the various eruptions. It is probable that the cone may rest upon sediments of Tertiary age, like the sister island of Oahu. The first word is equivalent to Mount, and the second signifies great or long. Some authors prefer to say Mount Loa rather than Mauna Loa. The natives call the caldera at the summit Mokuaweoweo. The great dome, so far as can be judged, is composed of overlapping sheets of basalt, both aa and pahoehoe. Those at the surface are of known age, or certainly younger than those that are deep seated. There are no large canyons upon its surface produced by the erosion of streams, because the deposition of the sheets is so recent. Above 10,000 feet there is scarcely any vegetation. The expanse is entirely composed of basalt showing evidences of many interlacing streams of lava. The surface is nearly level for the extent of four or five square miles. Mr. Ellis who explored Hawaii in 1823 has nothing to say of Mokuaweoweo, while he writes fully of Kilauea. Pele is located definitely at Kilauea. I have not yet discovered any native traditions respecting eruptions from the larger volcano. It may be that the earlier explorers were not aware of the character of Mauna Loa. Ellis represents it as covered by snow throughout the year. It is uninhabitable, and therefore its eruptions would not usually be fraught with disaster to the inhabitants, and thus would be scarcely mentioned in the traditions. When Hawai`i shall have been studied carefully it will be possible to give the sequence of several pre-historic eruptions. One of these is Keamoku, an expanse on the north side of the mountain adjacent to and underlying the flow of 1843. The fact that it is distinguished upon the Government map indicates that the surveyors were impressed by its recency. It starts from the cone of Kokoolau 8,000 feet high, and terminates at the altitude of 3,000 feet at the hill whose name is now applied distinctively to the flow itself. Its area is very much the same with that of the well known eruption of 1843, extending down hill for twenty-one miles, the first third of the way proceeding due north, and then to the northwest. The area of 1843 laps over the edge of Keamoku. I find very nearly the same name applied to an aa flow on the opposite side of the mountain, along which the new Kau Volcano road runs for several miles. This is supposed to be connected with a broad stream starting just below Puu Ulaula seven miles east of Mokuaweoweo. Upon most of the maps this stream is represented to have the date of 1823, and to have been connected with the discharge from Kilauea of that date, described by Mr. Ellis. This gentleman, however, makes no allusion to the existence of any recent stream descending from Puu Ulaula in that year, nor does he have anything to say about eruptions from Mauna Loa. Back to Contents

Early Historic Eruptions The first considerable knowledge of the Hawaiian Islands was acquired by Captain Cook in 1778-9. From the narrative illustrative of this expedition I find the following description of the features of a part of Hawaii, which all who are familiar with the island will recognize as truthful. "The 13 coasts of Kaoo present a prospect of the most horrid and dreary kind, the whole country appearing to have undergone a total change from the effects of some dreadful convulsion. The ground is everywhere covered with cinders, and intersected in many places with black streaks, which seem to mark the course of a lava that has flowed, not many ages back, from the mountain Roa to the shore. The southern promontory looks like the mere dregs of a volcano. The projecting headland is composed of broken and craggy rocks, piled irregularly on one another and terminating in sharp points." Back to Contents The First Known Attempt to Ascend Mauna Loa John Ledyard, the famous traveler, was one of the seamen of Captain Cook's party in 1779 when they were anchored off Kealakekua. I will quote the greater part of his narrative from A Journal of Captain Cook's last voyage to the Pacific Ocean and in quest of a northwest passage between Asia and America. Printed and sold by Nathaniel Patton, Hartford, Conn., 1783, On the 26th of January I sent a billet on board to Cook, desiring his permission to make an excursion into the interior parts of the country, proposing, if practicable, to reach the famous peak that terminated the height of the island. My proposal was not only granted, but promoted by Cook, who very much wanted some information respecting that part of the island, particularly the peak, the tip of which is generally covered with snow and had excited great curiosity. He desired the gunner of the Resolution, the botanist sent out by Mr. Banks and Mr. Simeon Woodruff, to be of the party. He also procured us some attendants among the natives to assist us in carrying our baggage and directing us through the woods. It required some prudence to make a good equipment for this tour, for though we had the full heat of a tropical sun near the margin of the island, we knew we should experience a different temperament in the air the higher we advanced towards the peak, and that the transition would be sudden, if not extreme. We therefore took each of us a woolen blanket, and in general made some alteration in our dress, and we each took a bottle of brandy. Among the natives who were to attend us was a young chief whose name was O'Crany and two youths from among the commonalty. Our course lay eastward and northward from the town, and about two o'clock in the afternoon we set out. When we had got without the town, we met an old acquaintance of mine (who ought indeed to have been mentioned before). He was a middle aged man, and belonged to the order of their Mida or priesthood, his name was Kunneava. We saluted each other, and the old man asked with much impatient curiosity where we were going; when we had informed him he disapproved of our intention, told us that we could not go as far as we had proposed, and would have persuaded us to return; but finding we were determined in our resolves, he turned and accompanied us; about two miles without the town the land was level, and continued of one plain of little enclosures separated from each other by low broad walls. Whether this circumstance denoted separate property, or was done only to dispense with the lava that overspread the surface of the country, and of which the walls were composed, I cannot say, but probably it denotes a distinct possession. Some of these fields were planted, and others by their appearance were left fallow. In some we saw the natives collecting the coarse grass that had grown upon it during the time it had lain unimproved, and burning it in detached heaps. The sweet potatoes are mostly raised here, and indeed are the principal object of their agriculture, but it requires an infinite deal of toil on account of the quantity of lava that remains on the land, notwithstanding what is used about the walls to come at the soil, and besides they have no implements of husbandry that we could make use of had the ground been free from the lava. If anything can recompense their labor it must be an exuberant soil, and a beneficent climate. We saw a few patches of sugar cane interspersed in moist places, which were but small. But the cane was the largest and as sweet as any we had ever seen; we also passed several groups of plantain trees. These enclosed plantations extended about three miles from the town, near the back of which they commenced and were succeeded by what we called the open plantations. Here the land began to rise with a gentle ascent that continued about one mile, when it became abruptly steep. These were the plantations that contained the breadfruit trees. After leaving the breadfruit forests we continued up the ascent to the distance of a mile and a half further, and found the land there covered with wild fern, among which our botanist found a new species. It was now near sundown, and being upon the skirts of these woods that so remarkably surrounded this island at a uniform distance of four or five miles from the shore, we concluded to halt, especially as there was a hut hard by that would afford us a better retreat during the night than what we might expect if we proceeded. When we reached the hut we found it inhabited by an elderly man, his wife and daughter, the emblem of innocent uninstructed beauty. They were somewhat discomposed at our appearance and equipment, and would have left their house through fear had not the Indians (natives) who accompanied us persuaded them otherwise, and at last reconciled them to us. We sat down together before the door, and from the height of the situation we had a complete retrospective view of our route, of the town, of part of the bay and one of our ships, besides an extensive prospect on the ocean, and a distant view of three of the neighboring islands. It was exquisitely entertaining. Nature had bestowed her graces with her usual negligent sublimity. The town of Kireekakooa and our ship in the bay created the contrast of art as well as the cultivated ground below, and as every object was partly a novelty it transported as well as convinced. As we had proposed remaining at this hut the night, and being willing to preserve what provisions we had ready dressed, we purchased a little pig and had him dressed by our host who rinding his account in his visitants bestirred himself and soon had it ready. After supper we had some of our brandy diluted with the mountain water, and we had so long been confined to the poor brackish water at the bay below that it was a kind of nectar to us. As soon as the sun set we found a considerable difference in the state of the air. At night a heavy dew fell and we felt it very chilly and had recourse to our blankets notwithstanding we were in the hut. The next morning when we came to enter the woods we found there had been a heavy rain though none of it had approached us notwithstanding we were within 200 yards of the skirts of the forest. And it seemed to be a matter of fact both from the information of the natives and our own observations that neither the rains or the dews descended lower than where the woods terminated, unless at the equinoxes or some periodical conjuncture, by which means the space between the woods and the shores were rendered warm and fit for the purposes of culture, and the sublimated vegetation of tropical productions. We traversed these woods by a compass keeping a direct course for the peak, and was so happy the first day as to find a foot-path that trended nearly our due course by which means we traveled by estimation about 15 miles, and though it was no extraordinary march had circumstances been different, yet as we found them, we thought it a very great one for it was not only exceedingly miry and rough but the way was mostly an ascent, and we had been unused to walking, and especially to carrying such loads as we had. Our Indian companions were much more fatigued than we were, though they had nothing to carry, and what displeased us very much would not carry anything. The occasional delays of our botanical researches delayed us something. The sun had not set when we halted yet meeting with a situation that pleased us, and not being limited as to time we spent the remaining part of the day as humour dictated, some botanizing and those who had fowling pieces with them in shooting; for my part I could not but think the present appearance of our encampment claimed a part of our attention, and therefore set about some alterations and amendments. It was the trunk of a tree that had fell by the side of the path and lay with one end transversely over another tree that had fallen before in an opposite direction, and as it measured 22 feet in circumference and lay 4 feet from, the ground, it afforded very good shelter except at the sides which defect I supplied by large pieces of bark and a good quantity of boughs which rendered it very commodious, and we slept the night under it much better than we had done the preceding, notwithstanding there was a heavy dew and the air cold; the next morning we set out in good spirits hoping that day to reach the snowy peak, but we had not gone a mile forward before the path that had hitherto so much facilitated our progress began not only to take a direction southward of west but had been so little frequented as to be almost effaced. In this situation we consulted our Indian convoy, but to no purpose. We then advised among ourselves and at length concluded to proceed by the nearest rout without any beaten track, and went in this manner about 4 miles further finding the way even more steep and rough than we had yet experienced, but above all impeded by such impenetrable thickets as would render it impossible for us to proceed any further. We therefore abandoned our design and returning in our own track reached the retreat we had improved the last night, having been the whole day in walking about 10 miles, and had been very assiduous too. We found the country here as well as at the seashore universally overspread with lava, and also saw several subterranean excavations that had every appearance of past eruption and fire. The next day about two o'clock in the afternoon we cleared the woods by our old rout, and by six o'clock reached the tents, having penetrated about 24 miles and we supposed within II of the peak. Our Indians were extremely fatigued though they had no baggage, and we were well convinced that though like the stag and the lion they appear fit for expedition and toil, yet like those animals they are fit for neither, while the humbly mule will persevere in both. According to an attitude of the quadrant, the Peak of Owyhee is 35 miles distant from the surface of the water, and its perpendicular elevation nearly 2 miles. The island is exactly 90 leagues in circumference, is very nearly of a circular form, and rises on all sides in a moderate and pretty uniform ascent from the water to the Peak, which is sharp and caped, as I have before observed, with snow, which seems to be a new circumstance, and among us not altogether accounted for. As a truth and a phenomenon in natural philosophy I leave it to the world. Owyhee has every appearance in nature to suppose it once to have been a volcano. Its height, magnitude, shape and perhaps its situation indicate not only that, but that its original formation was effected by such a cause. The eastern side of the island is one continued bed of lava from the summit to the sea, and under the sea is 50 fathoms water some distance from the shore; and this side of the island utterly barren and devoid of even a single shrub. But there is no tradition among the inhabitants of any such circumstance. Back to ContentsVancouver's Exploration The next English expedition to the Hawaiian Islands after the death of Captain Cook was that commanded by George Vancouver in the year 1793-4, published in 1798. Vancouver had visited the islands before, having been connected with the staff of Captain Cook. King George the Third commissioned him to explore distant lands for a term of four years and to aid, so far as possible, in the improvement of the early nationalities. Thus he was the agent of the importation of domestic cattle into Hawaii. The Hawaiian King placed a kapu upon them for ten years, which proved effectual for their continuance. At the present date it is possible to obtain descendants of these early cattle just as lions and elephants may be hunted in Africa. Sheep were also turned loose in the forests by Vancouver, but they did not survive long because they were hunted down by dogs. Other domestic animals that have reverted to the wild state are swine, horses, dogs, poultry and turkeys. Upon the eleventh of January, 1794, Vancouver observed columns of smoke arising from Kilauea, which were recognized as volcanic exhalations. After reaching the anchorage of Karakakooa parties were organized to explore the interior, under the direction of Archibald Menzies, the distinguished botanist. They first ascended Hualalai, or Worroway, which they found to be a volcano over 8,000 feet high, with several small well defined craters upon its summit, which were figured in the narrative. A second trip penetrated the forest between Hualalai and Mauna Loa for a distance of sixteen miles. Finally the successful attempt was made to ascend Mauna Loa. Vancouver did not present the results of this trip in his narrative, for some unexplained reason. Being fully persuaded that the manuscript account of this exploration must be in existence, I authorized Dr. Henry Woodward, the well known English geologist, to search for it in London, and through his efforts have come into possession of a copy. Because of its great value as a record of the first attempt to climb this mountain by Europeans, and of the condition of the volcano at that time, it is herewith presented in full. Back to Contents Archibald Menzies' Journal

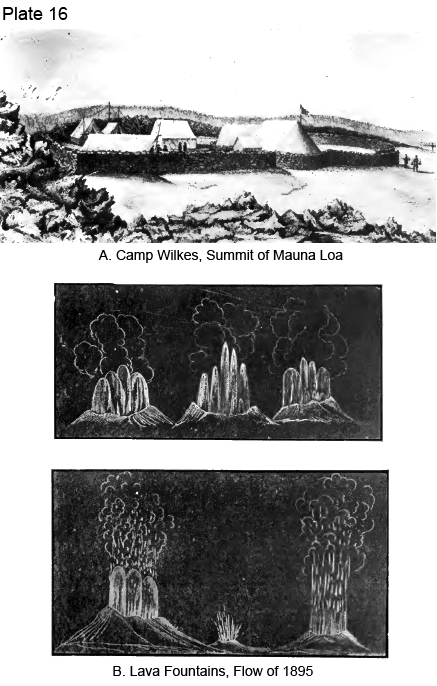

Other Statements The natives of Captain Wilkes' party in 1841 stated that there had been an eruption from the north Pohaku o Hanalei sixty years earlier, or about 1780. This accords with the specific statement of Keaweehu the bird catcher and guide who said there had been an eruption upon the mountain shortly after the death of Captain Cook. John Turnbull in his narrative of a voyage around the world from 1800 to 1804, says that as he was leaving Karakakooa, January 21, 1803, he had a full view of some eruptions from the volcanic center of the island of Owhyhee. This must have been upon the west or north side of Mokuaweoweo. He adds that "many parts of the surface of the island are covered with lava, calcined stones, black dust and ashes emitted by former eruptions." An indefinite statement was made by G. Poulett Scrope in his classic work upon volcanoes published in 1825. Upon his map he colors the Hawaiian Archipelago as volcanic: he says nothing of the observations of Ellis which were the only testimony from observations made on the island before that date; but remarks that navigators in the Pacific Ocean had seen lava flowing down the sides of Mauna Loa. Whether he made reference to the two instances quoted cannot be proved. It is very probable that Mokuaweoweo showed less activity after 1780 and before 1832 than in the decades since. Back to Contents Mokuaweoweo Between 1832 And 1843 Rev. Joseph Goodrich is authority for the statement that lava flowed from several vents about the summit on June 20, 1832. Light was observed from Lahaina on Maui, a hundred miles to the northwest. Lava was seen coming out of the sides of the mountain in different places. Discharges of red hot lava were seen on every side of the mountain. This would seem to indicate that these flows were like all the later ones, not from the summit, but from some weak spot lower down. The reflection of fire upon the clouds at the first was probably regarded as evidence of a flow from the summit. Earthquakes were noted on Hawaii during the summer and quite an important display of activity was manifested at Kilauea, probably a few months earlier (Jan. 12). The impression prevails that these eruptions from Mokuaweoweo and Kilauea were simultaneous; and to reach this conclusion we must believe that the writing Jan. was a printer's error for June, in the account of Kilauea. The records are meagre with respect to the location of this flow. The Government map shows a small area upon the south side of the caldera, and close to it, with the label of 1832. I have questioned everybody as to the authority for this representation, and no one connected with the Survey can give the information. Our doubt respecting this reference comes from the unusual position immediately adjacent to Mokuaweoweo. None of the eruptions on record later are so situated; they are lower down. Mr. Green refers its altitude to 13,000 feet in a table, but makes no remark concerning it in his text. The light was seen at Lahaina by Mr. Goodrich. That might have been the illumination always seen at the beginning of every flow. If the discharge was upon the south side it would not be very conspicuous from Maui. Mr. E. D. Baldwin suggests that there is a flow of recent lava, judging from its appearance, just inside o the great prehistoric Keamuku flow, arising near the beginning of the 1852 stream, which would have been visible from Lahaina, and might possibly have been erupted at this time. Keamoku is also well situated to answer the conditions even better, should the flow have been sufficiently recent. In 1834 the summit was visited by Dr. David Douglas, an exploring naturalist. Some of his statements have been discredited because of apparent exaggeration of the terrific activity of Mokuaweoweo. He used instruments for the determination of altitudes and areas. He represented that there were great chasms in the pit that he could not fathom, even with a good glass when the air was clear. Upon the east side he used a line and plummet, and obtained the figure of 1,270 feet for the height of the precipice. The southern part of the crater presented an old looking lava. He heard hissing sounds apparently connected with internal fire. The greatest portion of this huge dome was said to be a gigantic mass of slag, scoriae and ashes. Dr. Douglas lost his life shortly after his return from Mokuaweoweo. As his remains were found in a pit where wild cattle were entrapped it was supposed at first that he had accidentally fallen into it and was gored to death; but recently it has been ascertained that he had been thrown into this pit Jan. 27, 1834, by a bullock hunter named Ned Gurney, an Australian convict. This statement comes from Bolabola, an Hawaiian who was ten years old at the time of the homicide. He and his parents were intimidated by Gurney, so that fifty or sixty years passed before he was willing to testify to the nature of the transaction. S. E. Bishop says of this locality: In March, 1836, I looked into the pit where David Douglas perished. It was close to the inland trail from Waimea to Laupahoehoe, on the N. N. E. side of Mauna Kea, ten or fifteen miles northwest of Laupahoehoe and in the woods. Back to ContentsThe Wilkes Party Upon Mauna Loa The most elaborate attempt to take observations upon Mauna Loa was that of the United States exploring expedition in 1840-41. Captain Wilkes, the officer in command of the expedition, wished to apply the best apparatus of his time for the determination of geodetic positions and altitudes besides observing the volcanic phenomena and mapping the country. His ship anchored at Hilo. The party started December 14, 1840, and the last of them returned to Hilo, Jan. 23, 1841, making an absence of fortytwo days. Twenty-eight days were spent upon Mauna Loa; six days were required to make the ascent and two for the descent to Kilauea. At the beginning the company was to be compared to a caravan. It consisted of two hundred bearers of burdens, forty hogs, a bullock and bullock hunter, fifty bearers of poi, twentyfive with calabashes of different shapes and sizes, from six inches to two feet in diameter. Some of the bearers carried the scientific apparatus, others parts of the house to be erected on the summit, tents, knapsacks and culinary utensils. There were lame horses and as many hangers on as there were laborers. The natives moved under the direction of Dr. G. P. Judd, without whose help the expedition would have been a failure. After the start thirty more natives were added to the company so as to equalize the burdens. After passing Kilauea the number of the party was somewhat reduced, but there were still three hundred persons in all to be provided with food and water. Sickness and accidents led to the establishment of the Recruiting Station or hospital at the altitude of 9,745 feet. All the party experienced more or less of mountain sickness. The final encampment was on the edge of the pit of Mokuaweoweo, and the party suffered much from the inclement weather. There were a dozen separate tents and houses, all surrounded by a high stone wall. These are shown in Plate16A. Fifty men were detailed from the vessel to complete the undertaking. The serviceable natives returned down the mountain after the necessary articles had been brought up, and came back after the termination of the observations in order to transport this valuable apparatus back to the ship.

The following facts were stated about the mountain: Its whole area was of lava, chiefly of very ancient date, rough and seemingly indestructible, made up of streams that had flowed from the central vents for many ages. Both pahoehoe and clinkers (aa) abounded. Wilkes concluded that the clinkers were formed in the great pit where they were broken and afterwards ejected with the more fluid material. Their progress would have continued till the increased bulk and attendant friction arrested the stream. Pahoehoe seemed to have flowed from the clinker masses that had been stranded. The crater was likened to an immense caldron, boiling over the rim, and discharging the molten mass and scoria which had floated on its top.

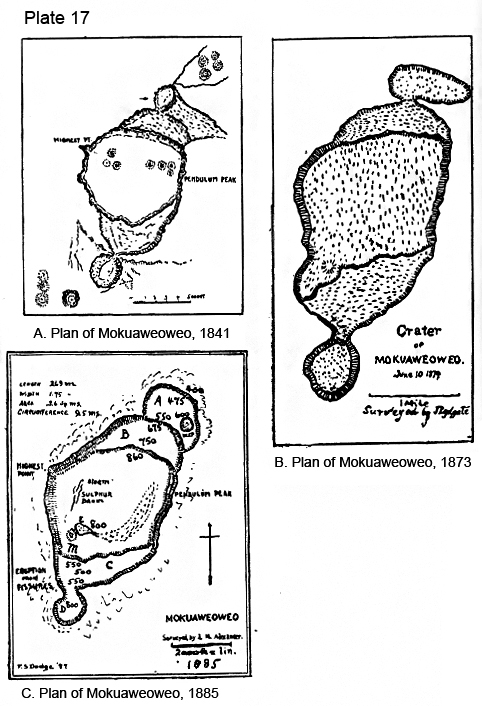

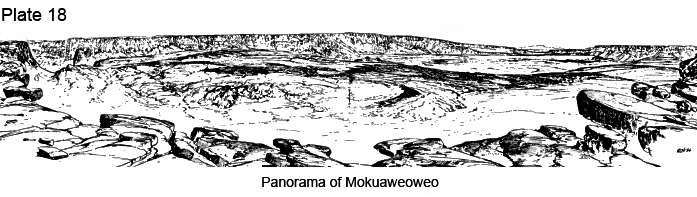

From the plan of Mokuaweoweo as given by Wilkes, Plate I7A, the following points may be made. The central part is the deepest, seven hundred and eighty-four feet by the west bank and four hundred and seventy feet by the east. This part is 9,000 feet in diameter nearly circular. The bottom is flat, with ridges from ten to fifty feet high, alternating with deep chasms and pahoehoe. Skirting this pit on both the north and south sides are lunate platforms apparently two-thirds as high as the summit rim, both together having an area perhaps half that of the main depression, and their outer rims coincide with the outline of the whole caldera. Just outside of both are smaller pits, the northern one two hundred feet and the southern nearly three hundred feet in diameter. The last has the name of Pohaku o Hanalei from Wilkes, showing seventy layers of basalt in the walls, and a cooled stream of lava that came from the larger crater. A smaller pit-crater is mapped to the south. There are many deep fissures about these pits and the lava has a very fresh appearance, being suggestive of obsidian. From the Pohaku o Hanalei a great steam crack points southerly. The highest point in the rim is opposite the encampment, with the altitude of 13,780 feet, three hundred and forty feet higher than at the station, which had the name of Pendulum Peak. Mauna Kea proved to be one hundred and ninety-three feet higher than Mauna Loa. Water boiled at 187° F. at Pendulum Peak. For some reason the main axis of Mokuaweoweo was placed at N. and S. instead of N. 26 E. It differed from Kilauea in the absence of a black ledge and a boiling lake and the evidences of heat were scant. There was one cinder cone at least upon the floor. Sodium and calcium sulphates, magnesium and calcium carbonates, ammonium sulphates and sulphurous gases were met with in the pit. The clinkers were compared to the scoriae from a foundry, in size from one to ten feet square, armed on all sides with sharp points. The fragments are loose with a considerable quantity of the vitreous lava mixed with them. As to origin, both the smooth and rough varieties are conceived to have been ejected in a fluid state from the terminal (summit) crater. The "clinkers" are seldom found in heaps, but lie extended in beds for miles in length, sometimes a mile wide, and occasionally raised from ten to twenty feet above the general slope of the mountain. The "clinkers" were formed in the crater itself, broken up by contending forces, ejected with the more fluid lava, which carried it down the mountain slope until arrested by the accumulating weight or by the excessive friction. They were streams of lava: and this opinion was fortified by the observation that pahoehoe came out from underneath the masses of clinkers wherever they had stopped. The crater was an immense caldron boiling over the rim. No facts are presented in favor of this view, and the idea was evidently borrowed from the conception of what a volcano should be. There had been no signal eruption previous to 1840 when the characteristic stream flows of this mountain had been developed. Back to ContentsEruption of 1843 According to Dr. Andrews, smoke was first seen from Hilo above the summit, January 9th. The next night a brilliant light appeared above the summit like a beacon fire. By day great volumes of smoke were poured forth, and for a week there was a fire by night. The summit fire was then transferred to a point near the ridge leading towards Hilo about 11,000 feet high. The lava flowed from two craters toward Mauna Kea, according to Mr. Coan, who ascended to the source of the flow. It was supposed at first that the eruption was an overflow from' the summit: this was before the behavior of the flows from very high up the mountain was understood. The lava spread out broadly from about the altitude of 11,000 feet to the base of the dome, and then rolled in a northwesterly direction towards Kawaihae more than sixteen miles. The lowest point of the stream in the saddle between Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea was near Kalaieha or the Humuula sheep station. Though so stated by Mr. Coan, the map does not indicate that a branch of the stream was directed toward Hilo. The greatest width of the stream was four and a half miles. The beginning of the outflow was less than a mile and a half from Pohaku Hanalei. It trespassed slightly upon the Keamoku flow, which started from Kokoolau at an unknown period and moved twenty miles to the Trig, station Keamoku, from 7,800 to 3,300 feet altitude. After the refrigeration of the surface of the lava, the melted material continued to flow under cover for more than six weeks. The angle of descent for the whole distance is six degrees, but occasionally there were steep pitches of twenty-five degrees. Large stones thrown upon the surface did not sink but were rapidly transported downwards and lost to sight. Mounds, ridges and cones were thrown up, from which steam, gases and hot stones were thrown. On March 6th snow was found upon the summit. During this eruption there was no sign of sympathy with it at Kilauea. From a native newspaper, Ka Hae Hawaii (The Hawaiian Banner), Rev. W. D. Westervelt has made the following translation of an account of the eruption of 1843, m tne Paradise of the Pacific, November, 1908. The eruption of January 10, 1843, was described by Mr. Coan. In the morning while it was still entirely dark a small flame of Pele fire was seen on the summit of Mauna Loa, on the northeastern shoulder of the mountain. Soon afterward the fire opened another door and the lava rushed down the side directly opposite Mauna Kea. Two 'branches were pouring forth lava, filling the place between the two mountains, covering it with fire like the spreading out of an ocean. One branch went toward the foothills of Hualalai and the other toward Mauna Kea until the flow came to the foot of the mountain, when it divided, one part going toward Waimea and one toward Hilo. Four weeks this eruption continued without cessation. The fires could not come to the sea coast, but filled up the low places of the mountain and spread out all over the different plains. Then it was imprisoned. Brilliant fires were noted at the summit in May, 1849, after the unusual activity in Kilauea. These lasted for two or three weeks, but there was no evidence of accompanying earthquakes or discharge of lava. Back to ContentsMokuaweoweo in 1851 There was a small flow on the west side of the summit commencing August 8, 1851. The smoke and fire were visible at Hilo. From Kona the light was gorgeous and glorious. Detonations were heard during the eruption, like the explosion of gases or rending of rocks. According to Professor Brigham, who visited the site in 1864, the starting point was 1,000 feet below the summit or two hundred feet below the floor of the caldera. The stream was ten miles long and less than a mile in width. Most of the lava was pahoehoe, with some aa, and seemed to have cooled rapidly. The course was westward, following very closely an earlier prehistoric flow reaching down to Kealakeakua. The eruption continued but three or four days. Back to Contents Eruption of 1852 The preceding eruption was really the opening scene of a fine exhibition six months later which started on the north side of the mountain, February i7th. On February 2Oth, the chief flow had shifted to another place about 10,000 feet above the sea level. The escaping lava rose at first in a lofty fountain, and then flowed easterly twenty miles. I quote quite extensively from Mr. Coan; Amer. Jour. Science, 1852.

Without specifying matters relating to the party and circumstances, I quote the text farther on:

In July Mr. Coan again visited the flow. The fires had ceased. A kind of pumice was very plentiful, beginning ten miles from the cone. It grew more and more abundant till the source of the flow was reached where it covered everything to the depth of five to ten feet. Messrs. H. Kinney and Fuller visited the source of this flow in March. Mr. Kinney described jets rising, from four hundred to eight hundred feet and represented the existence of a deep unearthly, roar, comparable to that of Niagara, heard a long distance away. The heat also created terrific whirlwinds. The two gentlemen agreed that the diameter of the crater from which the fountain rose was about 1,000 feet; the height of the crater from one hundred to one hundred and fifty feet; height of the fountain two hundred to seven hundred feet, rarely below three hundred; and the diameter of the fountain from two hundred to three hundred feet. The jet sometimes became a Gothic spire of two hundred feet, then after subsiding stood at three hundred feet with points comparable to architectural ornaments. Rev. D. B. Lyman of Hilo confirmed these estimates. The lava streams sometimes seem to have been two hundred to three hundred feet thick. Rev. E. P. Baker of Hilo visited the scene of this overflow in 1889 and found a single red cone in the midst of much pumice. There seemed to have been only one outlet. The lower part of the stream consisted of aa changing to pahoehoe higher up. Back to ContentsThe Eruption of 1852, described in verse by Titus Coan, and published in the Friend