Hawai`i and Its Volcanoes

|

Hawaii and Its Volcanoes by Charles H. Hitchcock, LL.D. of Dartmouth College EARTH SCIENCES LIBRARY, COPYRIGHT, 1909 BY THE HAWAIIAN GAZETTE Co., LTD PART 3: The History of the Exploration of Kilauea

Early Records of Activity at Kilauea Distribution of Volcanic Ashes about Kilauea

Eruption Of 1790 General Conclusions Concerning Both Volcanoes The Region of the Discharge of 1840 as Described by Wilkes

Eruption of 1849

Between

1855 and 1868

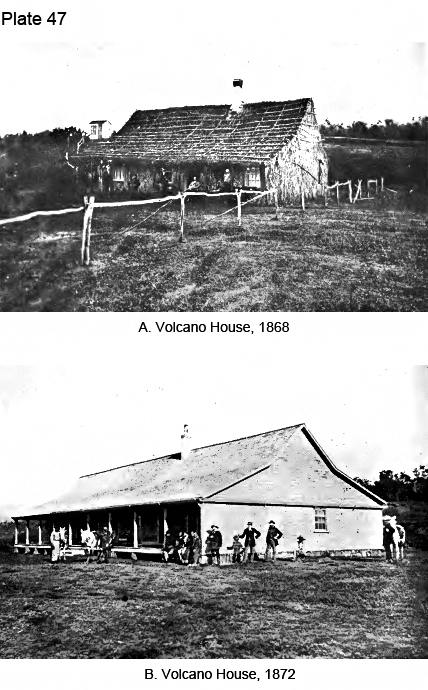

Kilauea, sometimes written Kilauea, is better known than Mauna Loa because it is more easily visited and has almost always afforded signs of volcanic activity. The altitude of its north bank at the Volcano House is given at 4,040 feet, and is easily reached by good carriage roads from Hilo on the northeast and the port of Honuapo on the southwest, being midway between these two villages. From Hilo there is also a steam railroad for three-fourths of the way, say twenty-five miles out of thirty-one. The ascent is gradual, at the rate of about one hundred and thirty feet to the mile, so that one does not realize that when standing on the brink of the caldera, he is really on the summit of a lofty mountain. There seems to exist data for a belief in a very extensive prehistoric flow from near Kilauea upon the Government road for over twenty miles southeasterly. At the higher 'elevations, from about the twenty-fifth to the thirtieth mile posts upon the Government road, the forest growth is wanting. The same is true of a broad strip of country makai of the trail used by travelers from Hilo to the volcano more than fifteen years ago. This trail, called the "worst road in the world," in my note books of 1883 and 1886, seems to have been located just outside of the forest, that belt which covers most of the country between Hilo and the Volcano. It is a magnificent growth of ohia, tree ferns, vines and other plants, answering to the appellation of jungle. The climatal conditions are favorable to its continuity over the whole of the region between the present forest and Puna; and it is our belief that the absence of vegetation is due to a large lava stream reaching from an older Kilauea to the lower limits of Olaa. There is a belt of the original growth between the caldera and the beginning of the scanty vegetation, from which immense trunks of the "Hawaiian mahogany" are now being obtained for commercial purposes. A recent trip from the ninth mile post out of Hilo on the Volcano road to Pohoiki (Rycroft's) confirmed these conclusions. Near the coast there is a dense growth of the Pandanus or louhala. Higher up it is replaced by various shrubs, especially the guava. The flow of 1840 is still conspicuous by the sparse vegetation upon it, as sufficient time has not yet elapsed to allow the complete disintegration of the basalt into soil and the consequent growth of trees; bushes appear upon the older lavas adjacent. The greater portion of this road between the flow of 1840 and the ninth mile post is situated upon a barren tract of pahoehoe, if possible more devoid of vegetation than the later stream, be cause Jess easily disintegrated. I found two small areas of the original dense forest in the midst of this barren tract. One is a mile in diameter, east of Pahoa post office; the other is much smaller, near the eighteenth mile post. Large ohias, tree ferns, ropy vines and various shrubs are as vigorous in these islands as in the upper forest, while the interspaces exhibit chiefly the pahoehoe, barren and devoid of vegetation. They are like the outliers of sandstone isolated in a flat country, and supposed to have once covered the whole region. The natural conclusion here is that the forest originally covered the whole of Puna and that a powerful flow of lava came from the barren tract east of Kilauea, burnt its way through the forest, leaving here and there islands of jungle. The general absence of vegetation would indicate that the date of the outflow is comparatively modern, recent enough to have been witnessed by the Hawaiians, and possibly preserved in legendary form. The first known reference to this volcano in the writings of Europeans is that given by Vancouver in 1794. Under date of January 11th, he writes: "As we passed the district of Opoona, (on ship board) the weather being very clear and pleasant, we had a most excellent view of Mauna Loa's snowy summit, and the range of lower hills that extend toward the east end of Owyhee. From the tops of these, about the middle of the descending ridge, several columns of smoke were seen to ascend, which Tamaahmaah and the rest of our friends said were occasioned by the subterranean fires that frequently broke out in violent eruptions, causing among the natives such a multiplicity of superstitious notions as to give rise to a religious order of persons, who perform volcanic rites, consisting of various sacrifices of the different productions of the country, for the purpose of appeasing the wrath of the enraged demon." Menzies in his sketch of the ascent of Mauna Loa refers to the "Volcano," from which smoke and ashes proceeded, making the air thick and irritating to the eyes. This was between Punaluu and Kapapala and his experiences were such as have been repeated constantly ever since. Before citing the account of the next visit to the volcano by an European, it will be well to state what has been learned from the native Hawaiian records, partly historic and partly legendary. Back to Contents Early Records of Activity at Kilauea As is well known, the first detachment of American missionaries arrived in Hawaii in 1820. They gradually made themselves familiar with the island and discovered the fact of the existence of the volcano of Kilauea. Because the natives possessed no written literature, it has been generally understood that their oral traditions transmitted from generation to generation had no scientific value. Historians have discovered that these traditions are of importance in determining the ancestry of the Hawaiians, and to some extent their chronology; and therefore credence may be given to their statements about volcanic activity. They imagined that the volcano was inhabited by certain deities, and rep resented that there were struggles among them and that they had the power to produce flows of lava, both superficially and by underground passages from the crater to the ocean. It may be said that these traditions represent the conceptions formed by the natives of the nature of the eruptions; and consequently the deeds performed can be recognized in one or another phase of volcanic activity. Furthermore, the events are said to have taken place during the reigns of particular kings and therefore make known the date of certain definite eruptions. I have not been able to investigate this history thoroughly, but have gleaned a few facts which may be added to by experts. The first information afforded by the missionaries is contained in a journal of a tour of exploration undertaken in 1823. Rev. William Ellis was an English missionary who had resided for several years in the Society Islands and had acquired a knowledge of the language of that part of the Pacific, which is very much like the Hawaiian tongue. With Rev. Daniel Tyerman and George Bennett, Ellis had explored some of the South Seas. The Hawaiian authorities invited Mr. Ellis, together with two Tahitian chiefs, to reside in Hawaii. The American Board of Commissioners of Foreign Missions took advantage of the opportunity afforded by the presence of these gentlemen to undertake the exploration of the island of Hawaii, primarily for evangelistic purposes, and incidentally for the acquisition of any knowledge of general importance. The missionaries connected with the A. B. C. F. M. who were associated with Mr. Ellis, were Reverends Asa Thurston, Artemas Bishop and Joseph Goodrich, and Mr. Harwood, an intelligent mechanic. All except Mr. Ellis arrived at Kailua, Hawaii, June 26, 1823. Before the arrival of Mr. Ellis, eight days later, the company had discovered various signs of volcanic structure, and attempted the ascent of Mauna Hualalai, but failed to reach the summit, for want of supplies. Back to Contents

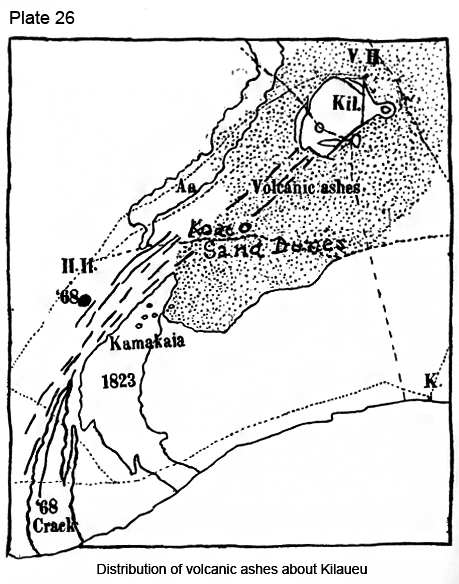

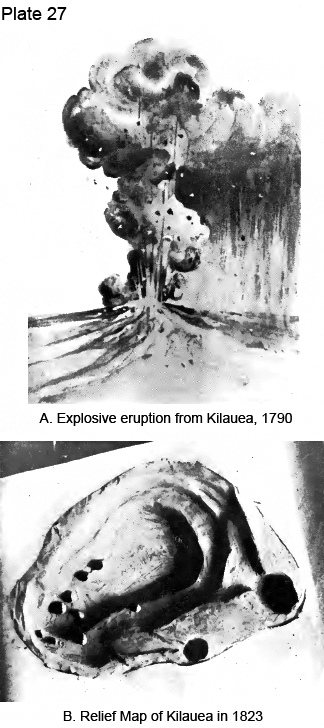

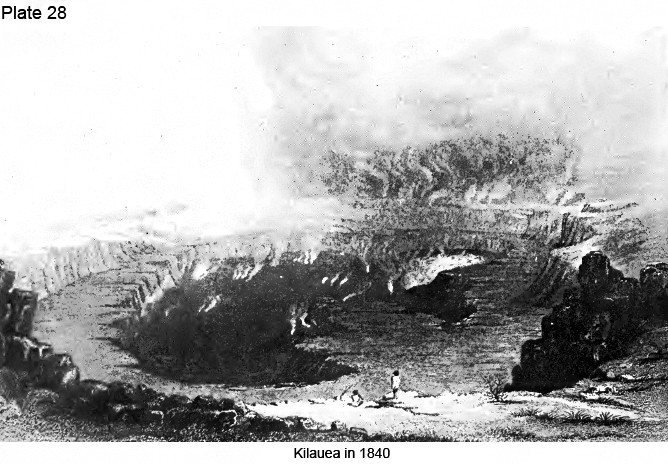

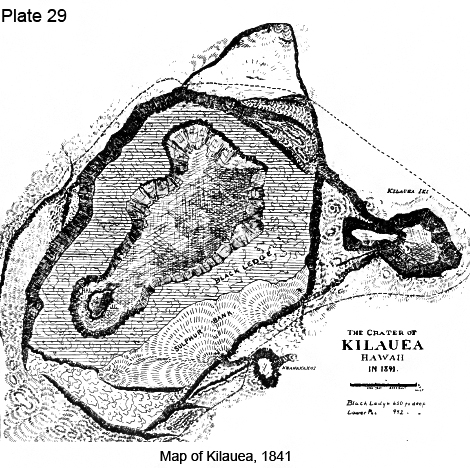

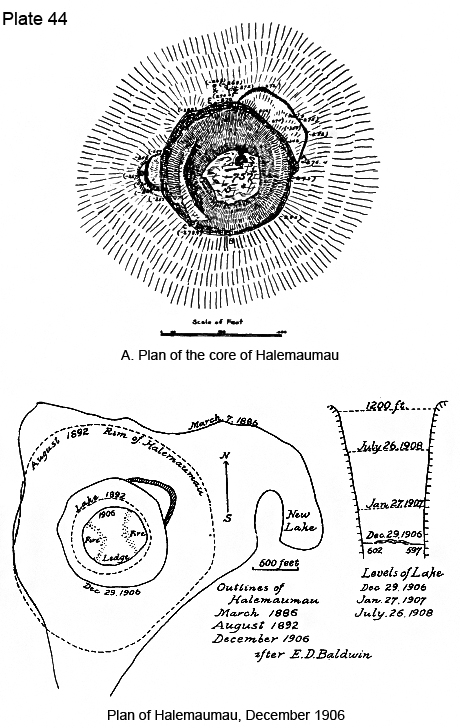

Distribution of Volcanic Ashes about Kilauea At length the journey around the island was commenced, and numerous references were made to volcanic phenomena, which need not be repeated. They journeyed through Kona and Kau till Kilauea was reached. They noted the conical hills of volcanic ashes not far from Tairitii, near Kahuku, which we now recognize as a part of the deposit blown out from Mokuaweoweo in prehistoric times. After passing the South Cape they began to see the clouds of smoke and to smell the fumes of sulphur emanating from Kilauea. From Kapapala they diverged on a side trip to Ponahohoa, a distance of five miles, where they saw the discharge that came from Kilauea in the month of March. The story was that the goddess of Pele had issued from a subterranean cavern and overflowed the lowlands of Kapapala. The inundation was sudden and violent. One canoe had been burnt and four others carried out to the sea. At Mahuka the deep torrent of lava had transported a huge rock, nearly one hundred feet high, into the water which was still visible. The ground at Ponahohoa exhibited several chasms, some of them ten or twelve feet across, from which smoke and steam was issuing. The vegetation had been scorched, and a considerable heat was still emanating from the recently ejected lava. This is the only notice we have of the 1823 eruption from Kilauea. In Plate 26 may be seen a sketch of its position and area, party of aa and partly of pahoehoe, occupying a space about fifteen miles square and surrounding the small hills known as Kearaarea. The plan is taken from the recent survey of Kapapala by E. D. Baldwin and George F. Wright, executed under the direction of Walter E. \Nail, Government surveyor. These small craters must have been formed long before this eruption, otherwise their names would not have been known. I have never seen any account of them, but they are quite conspicuous as seen from the Kau volcano road. After reaching Kaimu, several miles east of Kilauea, the deputation listened to accounts of an earthquake which had been experienced about two months earlier. The ground after several minutes of quaking had been rent for several miles in the direction north-by-east, and emitted a quantity of smoke, ashes and luminous vapor, but none of the people were injured. One house was situated directly over the chasm and the people were disturbed in their slumbers. Probably this disturbance was connected with the general eruption of 1823 from Kilauea. After Kilauea had been visited Mr. Ellis questioned the natives about its history. They represented that it had been burning from time immemorial: it often had boiled up and overflowed its banks in the earlier ages, inundating the surrounding country; but for many reigns past it had kept below the level of the surrounding plain, continually extending its surface, increasing its depth, occasionally throwing up large rocks and red-hot stones. These eruptions were always accompanied by dreadful earthquakes, loud claps of thunder and quick succeeding- lightning. No great eruption had taken place since the days of Keoua (1790), but many places near the sea had been overflowed; the streams of lava had taken subterranean courses to the shore. The first incoming of immigrants, as corroborated and dated by the historian Fornander, was in the days of Wakea, A.D. 190, when the volcano was active. The later immigration dates from A.D. 1090; and it was claimed that eruptions had taken place during every reign since that date; which may be estimated as once for every generation. The legend of Pele, detailed later, relates clearly to an eruption from Kilauea, which must have taken place a few years after 1175. About fourteen generations back, in the days of Liloa, 1420, a violent eruption broke out from Keanakakoi. As this seemed to be well known to the natives, it was probably of unusual importance, and is referred to again later. There was also an eruption at Kaimu in the days of Alapai, whose date proves to be from 1730 to 1754, according to Professor W. D. Alexander. Another tradition relates to the disturbances at Kapoho, a very interesting crater in Puna near the eastern extremity of Hawaii, belonging to Mr. Shipman, who entertained me in 1883, and later, to Mr. H. J. Lyman, whom I visited in 1899. Kapoho signifies the sunken in. It is the largest of all the craters in Puna, one mile in diameter, enclosing two hills and a pond of clear water, which is said to be quite saline. Inasmuch as Pele is represented as coming here to engage in the game of holua, it seems probable that Kapoho is connected with Kilauea. It was in the reign of Keariikukii, an ancient king of Hawaii, that Kahavari, a chief from Puna, with others, came to Kapoho to amuse themselves with sliding downhill. Many people came to witness the game, among them Pele. She challenged Kahavari to slide with her, and she was beaten. She asked for his sledge, which he refused to give her. Becoming incensed, she stamped upon the ground, whence followed an earthquake, rending the hill in sunder; and in response to her call liquid fire made its appearance, and pursued Kahavari. He had great difficulty in making his escape down the hill to the sea, whence he was closely followed by fire and stones while his family were overwhelmed. The special site of this action was the crater Kukii, a crater of black and red lapilli half a mile northeasterly from Lyman's. The scoriae are pumiceous like that on the south side of Kilauea. The time of Kahavari's domination in Puna is placed by Kalakaua at A.D. 1340 to 1380, in the resign of Kahoukapu. Another eruption was described by the natives as having been manifested about thirty-five years earlier, say 1788. There are three hills contiguous to each other, to the west of Kapoho, Honualula, Malama (Puulena) and Mariu (Kaliu). These arrested the progress of an immense torrent of lava which inundated the country to the north. This flow must have been analogous to the later discharge from Kilauea in 1840. One cannot resist the impression that the earlier eruptions were comparable with what are called the Vesuvian or explosive type of action; and Plate 27A is a humble attempt to represent the conditions attending the discharge of vapors, stones and ashes, when the whole adjacent region was covered with the ejectamenta. Back to Contents Eruption Of 1790 The account of the eruption of 1790 was compiled by Rev. Sheldon Dibble in his History of the Sandwich Islands, published at Lahainaluna in 1843. He interviewed several of the survivors of the catastrophe, and was able by repeated questionings to compile a satisfactory account of the events. It was also given by Mr. Ellis in his Journal. Rev. H. R. Hitchcock puts the date of the event at November, 1790, in the chronology of Hawaiian happenings appended to his Dictionary: others had supposed it to be a year earlier. In the earlier months of 1790 violent battles had been fought between Keoua and Kamehameha in their struggle for the supremacy, and now quite a large detachment of warriors were on the way to Kau under the leadership of Keoua, an immediate descendant of Taraiopu, a chief mentioned in Captain Cook's narrative. He took the route upon the southeast side of Kilauea and was encamped near Keanakakoi. The natives explained the disaster by the friendship of Pele for Kamehameha and hostility to Keoua. Soon after sunset there were repeated earthquakes, the rising of a column of dense black smoke followed by the most brilliant flames, and streams of lava spouted up in fountains and immense rocks were ejected to a great height. A volley of smaller stones thrown with great force followed the larger ones, striking some of the soldiers, and bursting like bomb shells, accompanied by lightning. Many of the people were killed by the falling fragments and others were buried beneath masses of scoriae and ashes. The natives did not dare to proceed. On the second and third nights there were similar disturbances. Not intimidated by this event Keoua continued his march, separating for safety into three companies. The advance party experienced a severe earthquake and a dense cloud rose out of the crater accompanied by electric discharges. The cloud excluded the light of day, but the darkness became more terrible because of the glare of the red-hot lava below and the flashes of lightning above. Soon afterwards there was a destructive shower, extending for miles around, of sand and cinders. A few persons were burned to death and others were seriously injured. All experienced a suffocating sensation and hastened on as rapidly as possible. The hindmost company which was nearest to the volcano seemed to suffer the least, and hastened forward after the eruption, congratulating themselves upon their escape. On reaching their comrades of the second company, said to be four hundred in number (Ellis says eighty), they were greatly surprised to find them all dead, although they retained life-like postures. Not one of the party survived, except a lone pig. The suddenness and totality of the destruction reads like the story of the disaster at Martinique, pouring down from Mont Pele; especially as Dibble adds: "A blast of sulphurous gas, a shower of heated embers, or a volume of heated steam would sufficiently account for this sudden death. Some of the narrators, who saw the corpses, affirm that though in no place deeply burnt, yet they were thoroughly scorched.” On their return, after the final battle in Kau, in about ten days’ time, the bodies were still entire and showed no signs of decay except a hollowness of the eyes. They were never buried, and one of the missionaries is reported to have seen many years afterwards a human skull lying in the volcanic sand Keoua himself surrendered to Taiana upon the hill of Makanao, one of the buttes in Hilea, described in connection with the caldera of Mohokea. It has been tacitly assumed that the place where the soldiers were destroyed was near Kilauea. The question arises would not the party have taken the regular road from Puna to Kau. If so, they would have been situated about five miles south from Kilauea. This trail is indicated upon Plate 26 by the dotted line leading from the east border of the map to the sand dunes, close by Koae and thence to the Halfway House. The first part of this trail follows a fault line. It would seem not improbable that the eruption came from some vent now concealed from view, because of the distance from Kilauea; but if all the material indicated upon the map as ashes and tuff came out in 1790, there could be no doubt as to its calamitous effect upon the army, for there is an enormous deposit of volcanic ashes, pumice, scoriae, lava bombs, stones and rocks spread over several miles between Keanakakoi and the road from Puna to Kau. It must be scores of feet in thickness. Were it removed; who knows how much farther the caldera beneath extends to the south and southwest!

This deposit must have been laid down by an eruption of the most violent type in prehistoric times long before the passage of the troops of Keoua from Hilo to Kau in 1790. It was a truly terrific discharge, fully equal to anything ever sent out from Vesuvius; and this enables us to affirm that Kilauea has sometimes belonged to the explosive class of volcanoes and has not always been the tame creature of today. Professor J. D. Dana explored the same region in 1887, and was fully persuaded that the material thrown out was connected with the historic event of 1790. "The distribution of the ejected stones, ashes and scoria all around Kilauea seems to show that the whole bottom of the pit was in action; yet the southern, as usual, most intensely so." The heavy compact basalts and their large use indicate that the more deep seated rocks along the conduit of the volcano had been torn off by the violent projectile action. "It was an explosive eruption of Kilauea such as has not been known in more recent times." Professor Dana observed three varieties of volcanic products about Kilauea that seemed to have been ejected explosively from the crater. At the base from twenty to twenty-five feet of yellowish brown tuff including very fine sand well exposed to view near fissures. Above the tuff are two or three feet of coarse conglomerate, including large stones; and on the summit twelve to sixteen inches thickness of a brownish sponge-like scoria, analogous to pumice, in pieces from half an inch across to two or three inches. Less than two per cent of this scoria is solid: it is a network like thread lace. One solid inch of the basalt glass would make a layer of scoria sixty inches thick. Because of its lightness it will float in water and may be easily carried off by the wind. It is most abundant south and west from the volcano; and may be seen near Uwekahuna and at the Volcano House. The stones are about the Volcano House and to the south of the caldera. Towards Keanakakoi, the ejected stones of one and two cubic feet are common; others are larger. The largest one seen contained one hundred cubic feet, and must weigh over eight tons. Stones like this are conspicuous from one-eighth to one-half a mile away from Kilauea. Some of them have been observed upon Uwekahuna. They consist of the more solid basalts of the neighborhood, usually of a gray color and somewhat vesicular. Some carry olivine and all appear to belong to early periods of formation. The tuffs and many stones make up the bulk of the cliffs to the south of the caldera. The recent (1907) map of Kapapala shows finely the distribution of this eolian deposit to the south and southeast. Not less than twenty square miles have been covered by it; extending for five miles southerly and southwesterly, or as far as to the ancient cone of Koae. There are several volcanic cones such as Kearaarea or Kamakaia in the midst of extensive fissures, both old and new. To the south of Koae are many large sand dunes that have been blown from the ash accumulations. On the other side of the fissures as one follows the regular road to Kau from Kilauea for nearly four miles, there are numerous patches of fine-grained drab tuff from two or three to six or more inches in extent with scoriaceous pieces and pisolitic spherules which are less conspicuous than the others, but of the same general character and age. Similar materials may be seen at the saw mill for koa lumber two miles from the Volcano House, and for four or five miles towards Glenwood, so that he entire area covered by the debris of explosive eruptions is estimated at more than sixty square miles. They are six feet thick in the new road around Kilauea iki. The following section has been made out: At the surface, small gravel stones with soil; Gravel two feet thick; Sand, becoming black below; Another foot thickness of sand; Pumice, a few inches thick, sometimes in pockets ; Rubble stones, some as large as cobbles; Underlying rock. The black seams are suggestive of a vegetable growth, indicating a lengthy period when plants were able to spread naturally from ,the surroundings, only to be covered later by the volcanic rain. The enormous area thus covered with explosive material renders it probable that the comparatively mild discharge of 1790 was inadequate to account for so extensive an inundation. There must have been several such discharges, perhaps recurring during centuries of time. Only a tithe of the stones spread over the surface would have been needed to destroy a much larger detachment than that suffocated in 1790. It would seem more consonant with the facts to connect the prolific tuffaeous and scoriaeous discharges with the days of Liloa rather than of Keoua; and perhaps Keanakakoi may have been the vent through which the discharge came. Certain observations made in 1905 may be significant here: Opposite Keanakakoi in the pit of Kilauea there was formerly exhibited upon the maps a "sulphur bank," now mostly covered by the black ledge. A narrow promontory still extends westerly to the south of Halemaumau, terminating at Kapuai and only slightly elevated, and covered with eolian debris. At the southwest end of the wall from Poli o Keawe there is an abrupt change from basalt to scoriae, and as you climb to this rock from the gravel a marked fault appears with a S.W. direction. On looking backwards there is a noticeable dip of the layers towards the old sulphur bank-perhaps of ten degrees. The fault seems to be the same with that figured by Professor W. H. Pickering. It seems apparent that the tuffs came from Keanakakoi, unless they represent the inward slope of the material blown out from Kilauea, such as falls toward the vent in tuff cones. Most of the cliff encircling the south curve of Kilauea is composed of similar materials. Dr. Brigham speaks of several shallow pits in this tuff that were made by the falling down or washing into fissures the finer parts of the sand and gravel. All these facts impress one with the magnitude and unusual character of the materials erupted about Keanakakoi. While there has been uncertainty about the date and origin of the various Kau accumulations of dust, it is refreshing to be able to present the views of Mr. E. D. Baldwin, obtained recently as the result of his survey for the Kapapala map. He finds that much of the fine volcanic ash has been derived from a Kilauean source; while there were earlier discharges in lower Kau and at Ka Lae not thus accounted for. These have been mentioned elsewhere in connection with the history of Mauna Loa. Back to Contents E. D. Baldwin upon the Yellow Ashes of Kau As to the sources of the yellow ash eruption, I would state, that I found a partial old yellow cone in among the Kamakaia hills, or the hills some three miles back of the Halfway House. The first source of the 1823 flow was three miles above these hills, from a long fissure, and then it seems to have broken out again, in its line of flow at these hills, forming the two larger cones. Near the large cone are two ancient cones, surrounded by the new lava, one of these was completely spattered and plastered over by the ejections from the large cone; it was on this cone, while riding along its base, that my horse broke through the crust, and while floundering around for a footing brought up large quantities of yellow tufa, of exactly the same nature as the black tufa, only it was of a beautiful yellow ocher color. On investigation I found that a large portion of this cone was composed of the same material. About a mile below Kamakaia hills, in the middle of the 1823 flow, is what we call the yellow cone. This cone had attracted my attention several times from a distance, as being of a yellowish color on all sides that we had observed it from. I thought, of course, that like the little sharp cone, Puu Kou, between it and the Kamakaia hills, it was a portion of the 1823 lava flow, but when we went out to the cone, we found that it was the top of an old cone sticking up through the 1823 flow, which flow had run all around the same, and into the crater of the cone. This cone was very interesting, its formation was exactly the same as all of the dark colored tufa cones, with the exception of color, which was entirely of the yellow tufa, which, when crushed in the hand to fine powder, had exactly the same appearance as the Kau yellow soils. In the crater of the cone were the same brilliantly red tufas that you find in the craters of all other cones. The top of the cone stands forty or fifty feet above the 1823 flow, and must be several hundred feet in circumference at the flow line. At this point the land lays more or less level, with a gentle slope towards the sea, so that the 1823 flow seems to have piled up to a great height and spread out to over a mile wide; showing that this was a very large cone in its original state. There are further evidences of the yellow eruptions some ten miles from these cones mentioned above. The great hill Puu Kapukapu, at the sea coast, is largely composed of the Kau yellow soil, also just to the Kau side of this hill, is the great hill Puu Kaone, having a low flat top, containing sixty acres of first class agricultural land, composed entirely of the Kau yellow soil of a depth of over thirty feet, as observed in the little rain-washed gullies on the same. Also on the face of the great pali or fault line, near the top, on a line towards Kamakaia hills from Puu Kapukapu, I noticed a large yellow patch. None of the sources of the yellow eruptions, that I have mentioned, would account for the lower Kau yellow soil, and that on the Kau side of Ka Lae or South Point, as the prevailing winds in this district seem to sweep from the volcano (Kilauea) down past the Kamakaia hills, and from there they meet the winds coming around from the sea coast, which seem to turn the air currents inland again. My theory is, that at some ancient period, there was a great line of yellow eruptions, extending from Puu Kapukapu (near Keauhou), past the Kamakaia hills to the lower portion of Kau, and that the sources of this yellow eruption in the lower part of Kau have been covered up with later flows, or other volcanic action, and that the great beds of yellow soil that we find today all over Kau, were blown there from these sources, before they were covered up. All of the yellow soil on the Pahala plantation, or towards the volcano from Pahala, is directly on the line of the prevailing winds from the direction of Kamakaia hills, Yellow cone, and a short ways below the same. I have especially noticed in the cuts on the Volcano-Kau road, just above the Pahala mill, that the old aa formation seems to be full of this yellow dust. If one will go and study the action of the wind on the great masses of volcanic sand being blown, at present, from Kilauea towards Kamakaia hills, it will be noted that when this sand strikes an aa flow, its forward progress is stopped, until it has filled and sifted into all of the little crevices of the aa. From Kilauea to near Kamakaia hills is a nearly barren field of pahoehoe, and the sand is driven along this space at a great pace, until it reaches the aa at the Kamakaia hills, and there it has been blocked up and is in many cases forming numerous sand dunes. Some of these sand dunes are very extensive, being four or five hundred feet long and over fifty feet high. Back to Contents Ellis' Description of Kilauea The first edition of the Journal of the Tour Around Hawaii was published in 1825. Eight years later it was reprinted with additions and emendations as Polynesian Researches, in four volumes and some of the original statements were modified. There were English editions also. I will utilize the additions and corrections given in the later edition. "We found ourselves," he says, "on the edge of a steep precipice (Uwekahuna) with a vast plain before us, seven and one-half miles in circumference, and sunk at least eight hundred feet below its original level. The surface of this plain was uneven, and strewed over with large stones and volcanic rocks. A place was found at the north end where a descent to the plain below was found practicable, and even yet the stones gave way under their feet causing them to fall and receive bruises. The rocks were of a light red and gray lava, vesicular, and lying in horizontal strata, varying in thickness from one to forty feet. In a small number of places the different strata of lava were also rent in perpendicular or oblique directions, from the top to the bottom, either by earthquakes or other violent convulsions of the ground connected with the action of the adjacent volcano. The immense gulf has the form of a crescent two miles long from northeast to southwest and a mile in width. The bottom was covered with lava, and the southwest and northern parts of it were one vast flood of burning matter, in a state of terrific ebullition, rolling to and fro its "fiery surge" and flaming billows. Fifty one conical islands (spiracles), of varied form and size, containing as many craters, rose either round the edge or from the surface of the burning lake. Twenty-two constantly emitted columns of gray smoke or pyramids of brilliant flame; and several of these at the same time vomited from their ignited mouths streams of lava, which rolled in blazing torrents down their black indented sides into the boiling mass below." Next follows a paragraph added in the later edition, a theoretical deduction. "The existence of these conical craters led us to conclude that the boiling caldron of lava before us did not form the focus of the volcano; that this mass of melted lava was comparatively shallow; and that the basin in which it was contained was separated, by a stratum of solid matter, from the great volcanic abyss, which constantly poured out its melted contents through these numerous craters into this upper reservoir. We were further inclined to this opinion from the vast column of vapor continually ascending from the chasms in the vicinity of the sulphur banks and pools of water, for they must have been produced by other fire than that which caused the ebullition in the lava at the bottom of the great crater; and also by noticing a number of small craters in vigorous action, situated high up the sides of the great gulf, and apparently quite detached from it. The streams of lava which they emitted rolled down into the lake and mingled with the melted mass, which, though thrown up by different apertures, had perhaps been originally fused in one vast furnace.'' "The sides of the gulf before us, although composed of different strata of ancient lava were perpendicular for about (nine) hundred feet (as calculated by Lieut. Malden later) and rose from a wide horizontal ledge of solid black lava of irregular breadth, but extending completely round. Beneath this ledge the sides sloped gradually towards the burning lake, which was, as nearly as one could judge, three or four hundred feet lower. It was evident that the large crater had been recently filled with liquid lava up to the black ledge, and had by some subterranean canal emptied itself into the sea, or upon the lowland on the shore." And he goes on to suggest that this discharge was what they had seen at Ponahoahoa a short time previously. This eruption is reported at one time two moons and at another five moons earlier than that date of August 1st. I have already presented a figure illustrating this flow to the southwest. It has been difficult to be entirely satisfied with some of the details offered in this sketch, because of repetitions, and of differences in the accompanying sketches. The first are explained by the supposition that to the original statement additions were made by others of the party; and the second may be due to the artist or engraver who make changes to suit fancy. The earlier account of all the Hawaiian volcanoes have been more or less influenced by a supposed similarity to Vesuvius. Instead of reproducing the sketches, I will present a restoration of what seem to me to be the true delineation of the cliffs, the black ledge and the lakes of fire, as they appeared in 1823, Plate 27B. The verbal description of the volcano given above by Mr. Ellis represents things as seen from Uwekahuna, but the views published must have been taken from the opposite side of the pit, showing the place on which he stood when he obtained his impressions. The descriptions of the two sulphur banks correspond to what have been seen later by others. The one at the north end was said to be about one hundred and fifty yards long, and thirty feet high at the maximum, showing much sulphur mixed with red clay. The ground was hot; fissures seamed the surface through which thick vapors continually ascended. Fine crystals of sulphur appeared in acicular light yellow prisms near the surface; those lower down were of an orange-yellow color in single or double tetrahedral pyramids an inch long. Ammonium sulphate, alum and gypsum frequently incrusted the stems. The other sulphur bank was larger and the sulphur more abundant, but they did not find time to examine it carefully. Both these banks correspond to what is now called a solfatara. The view by night was impressive. "The agitated mass of liquid lava, like a flood of melted metal, raged with tumultuous whirl. The lively flame that danced over its undulating surface, tinged with sulphureous blue, or glowing with mineral red, cast a broad glare of dazzling light on the indented sides of the insulated craters, whose roaring mouths, amid rising flames and eddying streams of fire, shot up, at frequent intervals, with very loud detonations, spherical masses of fusing lava or bright ignited stones." Mr. Ellis correctly named the rock, calling it basalt containing fine grains of feldspar and augite, with olivine. He also found zeolites and described the volcanic glass called Pele's hair by the natives. He conceived it to have been produced by a separation of fine spun threads from the boiling fluid, and when borne by the smoke above the edges of the crater had been wafted by the winds over the adjacent plain. He examined several of the small craters, which from above had appeared like mole hills, and found them to be from twelve to twenty feet high. The outside was composed of bright shining scoria and the inside was red with a glazed surface. He also entered several tunnels through which the lava had flowed into the abyss, and correctly ascribes their origin to the formation of the roof and sides by the cooling of the exterior, while the liquid for a time continued to flow in the inside. Professor Dana thinks that the fan figured on the west wall in the first sketch of the south end of the volcano was one of these tunnels, but it seems to me that it was only a fan of gravelly scoriae. It appeared as an isolated cone in the second sketch, detached from the wall, probably because the engraver did not know what else to do with it. Dr. S. E. Bishop tells me that this fan was very conspicuous when he first visited the volcano seventy years ago, and at his suggestion I looked for it in 1905 and could identify its location. Probably the tunnels were upon the eastern side, where later flows, such as those made in 1832, are still in evidence. These tunnels were represented as being hung with red and brown stalactitic lava, while the floor appeared like one continued glassy stream. The riffle of the surface was as well defined as if the lava had suddenly stopped and become indurated before it had time to settle down to horizontality. It would appear from what has been stated that there was more than one lake of fire at this time, and that there was a great abyss into which the surplus lava from the higher lake and the streams through the tunnels had accumulated. Mr. Ellis also speaks of the two side craters Keanakakoi and Kilauea iki, thus proving that these names were in use in 1823, and he seems to have been the originator of the expression "black ledge," which represented the level assumed by the molten lava before the recent discharge to the southwest. He speaks of many masses of grey basaltic rock, weighing from one to four and five tons, and surmised that they had been ejected from the great crater during some violent eruption. Not to present more of his truthful descriptions, I will refer only to his final speculation of the extent of the present subterranean fires. The whole island of Hawaii was said to be "one complete mass of lava, or other volcanic matter in different stages of decomposition. Perforated with innumerable apertures in the shape of craters, the island forms a hollow cone over one vast furnace, situated in the heart of a stupendous submarine mountain, rising from the bottom of the sea," etc. Back to Contents The Belief in Pele The apprehensions uniformly entertained by the natives of the fearful consequences of Pele's anger prevented their paying very frequent visits to the vicinity of her abode; and when, on their inland journeys, they had occasion to approach Kilauea, they were scrupulously attentive to every injunction of her priests, and regarded with a degree of superstitious veneration and awe the appalling spectacle which the crater and its appendages presented. The violations of her sacred abode, and the insults to her person, of which we had been guilty, appeared to them, and to the natives in general, acts of temerity and sacrilege; and, notwithstanding the fact of our being foreigners, we were subsequently threatened with the vengeance of the volcanic deity under the following circumstances. "Some months after our visit to Kirauea, a priestess of Pele came to Lahaina, in Maui, where the principal chiefs of the islands then resided. The object of her visit was noised abroad among the people, and much public interest excited. One or two mornings after her arrival in the district, arrayed in her prophetic robes, having the edges of her garments burnt with fire, and holding a short staff or spear in her hand, preceded by her daughter, who was also a candidate for the office of priestess, and followed by thousands of the people, she came into the presence of the chiefs; and having told who she was, they asked what communications she had to make. She replied that, in a trance or vision, she had been with Pele, by whom she was charged to complain to them that a number of foreigners had visited Kilauea; eaten the sacred berries; broken her houses, the craters; thrown down large stones, etc. to request that the offenders might be sent away and to assure them, that if these foreigners were not banished from the islands, Pele would certainly in a given number of days, take vengeance, by inundating the country with lava, and destroying the people. She also pretended to have received in a supernatural manner, Rihoriho's approbation of the request of the goddess. The crowds of natives who stood waiting the result of her interview with the chiefs were almost as much astonished as the priestess herself, when Kaahumanu, and the other chiefs, ordered all her paraphernalia of office to be thrown into the fire, told her the message she had delivered was a falsehood, and directed her to return home, cultivate the ground for her subsistence, and discontinue her deceiving the people. This answer was dictated by the chiefs themselves. The missionaries at the station, although they were aware of the visit of the priestess, and saw her, followed by the thronging crowd, pass by their habitation on the way to the residence of the chiefs, did not think it necessary to attend or interfere, but relied entirely on the enlightened judgment and integrity of the chiefs, to suppress any attempt that might be made to revive the influence of Pele over the people; and in the result they were not disappointed, for the natives returned to their habitations, and the priestess soon after left the island, and has not since troubled them with threatenings of the goddess. "On another occasion, Kapiolani, a royal princess, the wife of Naihe, chief of Kaavaroa, was passing near the volcano, and expressed her determination to visit it. Some of the devotees of the goddess met her and attempted to dissuade her from her purpose; assuring her that though foreigners might go there with security, yet Pele would allow no Hawaiian to intrude. Kapiolani, however, was not to be thus diverted, but proposed that they should all go together; and declaring that if Pele appeared, or inflicted any punishment, she would then worship the goddess, but proposing that if nothing of the kind took place, they should renounce their attachment to Pele, and join with her and her friends in acknowledging Jehovah as the true God. They all went together to the volcano; Kapiolani, with her attendants, descended several hundred feet towards the bottom of the crater, where she spoke to them of the delusion they had formerly labored under in supposing it inhabited by their false gods; they sang a hymn, and after spending several hours in the vicinity, pursued their journey. What effect the conduct of Kapiolani, on this occasion, will have on the natives in general, remains to be discovered." Back to Contents

KAPIOLANI

(Kapiolani was the daughter of Keawemauhile, the former king of Hilo,

slain by Keoua in 1790.) When from the terrors of nature a people Have fashioned and worshipped a Spirit of Evil, Blest be the voice of the teacher who calls to them, "Set yourselves free!"

Noble the Saxon who hurled at his idol A valorous weapon in olden England! Great, and greater, and greatest of women, Island heroine, Kapiolani, Clomb the mountain, and flung the berries, And dared the Goddess, and freed the people Of Hawaii! This people – believing that Pele the Goddess, Would swallow in fiery riot and revel On Kilauea, Dance in a fountain of flame with her devils, Or shake with her thunders and shatter her island, Rolling her anger Through blasted valleys and flowing forest In blood-red cataracts down to the sea!

Long as the lava light glares from the lava lake, Dazing the starlight; Long as the silvery vapor in daylight Over the mountain floats, will the glory Of Kapiolani be mingled with either On Hawaii. What said her Priesthood, "Woe to this island if ever a woman should handle Or gather the berries of Pele! Accursed were she!

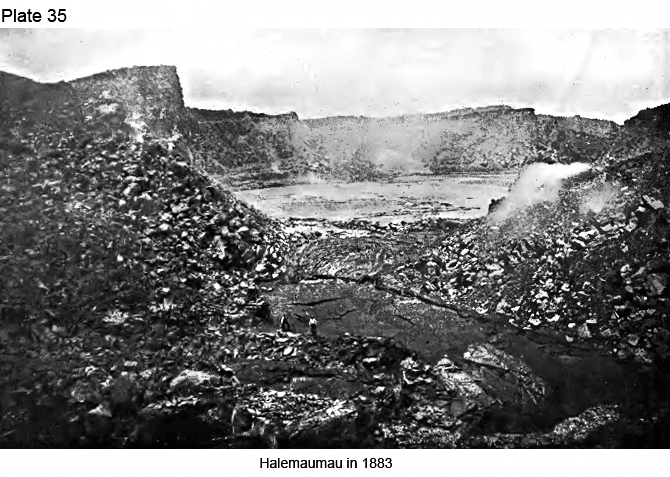

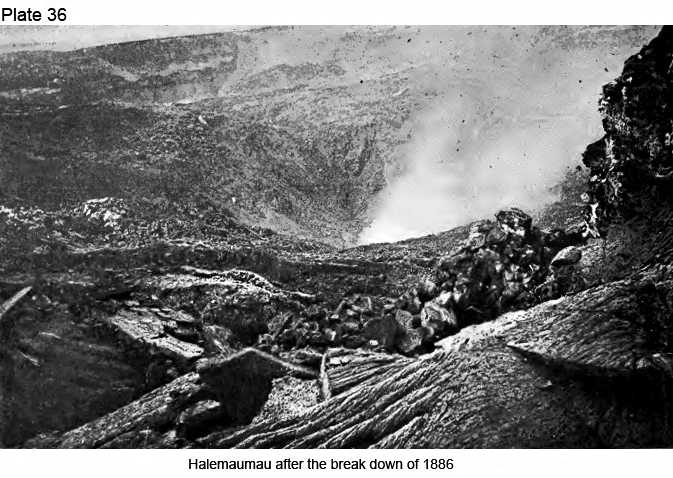

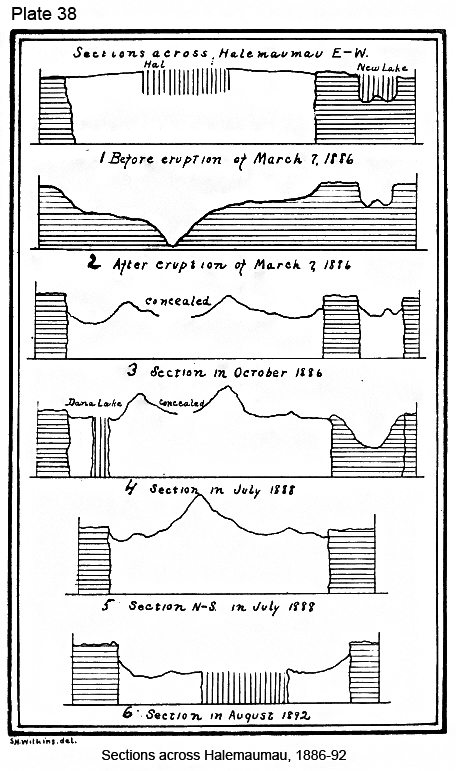

And woe to this island if ever a woman Should climb to the dwelling of Pele the Goddess! Accursed were she!" One from the sunrise dawned on His people, And slowly before Him vanished shadow-like Gods and Goddesses, None but the terrible Pele remaining, As Kapiolani ascended her mountain, Baffled her priesthood, broke the tabu, Descended the crater, Called on the Power adored by the Christian, And crying, "I dare her! Let Pele avenge herself!" Into the flame dashed down the berries, And drove the demon from Hawaii! Back to Contents The True Story of Pele King Kalakaua recovered from the traditions handed down for many generations the true story of Pele, and has presented it in his book under the heading of The Apotheosis of Pele. It seems that there was a large family, five brothers and nine sisters, emigrating from Tahiti during the reign of Kamiole the usurper about A.D. 175. Their names are given by Ellis as follows: Kamohoarii; Tapohaita hiora (the explosion in the place of life); Teuaatepo (the rain of night); Tanehetiri (husband of thunder or thundering Tane) and Teoahitamatana (fire-thrusting child of war). These were all brothers, two of them like Vulcan being humpbacked. The sisters were Pele, the principal goddess; Makorewawahiwa (fiery-eyed canoe breaker); Hiataholani (heavenrending cloud holder); Hiatanoholani (heaven-dwelling cloud holder); Hiatata aravamata (quick-glancing-eyed cloud holder, or the cloud holder whose eyes turn quickly and look frequently over her shoulders); Hiatahoiteporiopele (the cloud holder embracing or kissing the bosom of Pele); Hiatatabuenaena (the red-hot mountain holding or lifting clouds); Hiatatareia (the weather 'garland-encircled cloud holder); and Hiataopio (young cloud holder). This family with many others in their train settled about Kilauea. Pete was a valiant warrior. Kamapuaa was attracted by the merits of Pele, visiting Kilauea, and made proposals to become her guest and suitor. In many of the annals he is represented as half human and half hog-but Kalakaua explains that he was simply a rough, stalwart man with coarse black bristly hair of unprepossessing appearance, and called a half hog in derision. Pete rejected his proposals with contempt, calling him a hog and the son of a hog. A combat ensued, and the Pele family were worsted, and retreated to one of the long volcanic tunnels marking the course of an earlier lava flow ,and the entrance was closed. The party consisted of two men and eighteen women and children. Kamapuaa finally discovered the retreat and dug down into it from above. Just then there came a flow of lava which drove away the besiegers, who believed the people within the cave had been destroyed. Because of this timely eruption it was believed that Pele had the power of calling up the fire, and she became apotheosized as a goddess. As time went on the various eruptions were ascribed to some of Pete's movements. The whole island was considered bound to pay tribute; and if the proper offerings were not given to her votaries the caldera would be filled with lava and made to follow the delinquents. Back to Contents Kilauea in 1824 In 1824 Kilauea was visited by E. Loomis, June 16th, who came from the southwest. After reaching a point two miles from the crater he was annoyed by smoke blowing in his face, accompanied by sulphur fumes. The air, too, was filled with fine particles of sand, rendering it necessary to protect his face from their impact; and the surface of the ground was covered by it, his feet sinking into it six or eight inches at every step. From crevices five miles west of the crater smoke was issuing, and occasionally the forced ejection was great enough to produce an irregular hissing sound. At the southwest end of the volcano the smoke was so dense that little could be seen, and farther on much rain fell. He took the road on the east side. From two hundred and fifty to three hundred feet below the edge was a level platform, extending entirely around the crater, which was evidently the "black ledge" of Ellis. This platform was fifteen rods wide where he descended, probably near the "sulphur banks" as now designated. He had little difficulty in reaching the black ledge. Having now descended six hundred feet, Mr. Loomis walked upon the lower platform whose surface was smooth, though not level, rising in heaps like cocks of hay and broken by innumerable fissures. The lava was black, porous like pumice, and traversed by crevices emitting very hot steam. Proceeding eight or ten rods he reached another escarpment of two hundred or three hundred feet deep leading to the floor of the most active portion, from which smoke and flames of fire were issuing. There seemed to be small craters (spiracles) where the fire burst forth attended by a horrid noise. He was quite disappointed in not finding this lowest platform a mass of liquid fire, as it had been the year previous. The surface had become hard, and he presumed he could have walked over it safely but he did not descend to it as the sides were too steep to allow of a comfortable passage. This record is quite important, as it shows a period of comparative quiet at the center of eruption following the intense activity reported by Ellis in the previous year. Back to Contents Visit of Lord Byron In the year 1825, July 28th, a party from the "Blonde" visited the crater, Lord George Anson Byron being the leader. Others were Rev. C. C. Stewart and Lieut. Malden, the historians, and R. Dampier, the artist. The hut used by the company was situated upon the narrow plain between Kilauea and Kilauea iki. It had been erected a year or two earlier for the accommodation of Kapiolani. Lieut. Malden calculated the height of the upper cliff, Uwekahuna, to be nine hundred feet above the black ledge, and the depth of the lower pit at six hundred feet, a total of 1,500 feet. The circumference of the edge of the black ledge was from five to seven miles and that of the top from eight to ten miles Mr. Stewart speaks of the black ledge as a kind of gallery, in some places only a few feet, in others many rods wide. The gulf below contains as many as sixty small conical craters, many in constant action. The tops and sides of two or three of these are covered with sulphur, showing mingled shades of yellow and green. The upper cliffs on the northern and western sides are of a red color. Those on the eastern side are less precipitous and are largely composed of sulphur. The south end was wholly obscured by smoke which was impenetrable. The chief seat of action seemed to be at the southwestern end (Halemaumau). To the north of this is one of the largest of the smaller craters-one hundred and eighty feet high-an irregularly shaped inverted funnel of lava covered with clefts, orifices and tunnels, from which bodies of steam escaped with deafening explosion, while pale flames, ashes, stones and lava were propelled with equal force and noise from its ragged and yawning mouth. On the evening of the following day (29th) after terrific noises and tremblings of the ground, "a dense column of heavy black smoke was seen rising from the crater directly in front of us – the subterranean struggle ceased – and immediately afterwards flames burst front a large cone, near which we had been in the morning, and which then appeared to have been long inactive. Red-hot stones, cinders and ashes, were also propelled to a great height with immense violence; and shortly after the molten Java came boiling up, and flowed down the sides of the cone and over the surrounding scoriae, in two beautifully curved streams." At the same time a lake of molten lava two miles in circumference made it appearance. Rev. Artemas Bishop, in December, states that the pit was not so deep as in 1823 at the time of Ellis' visit by as much as four hundred feet. There were also Jakes of lava, frequently discharging gusts of vapor and smoke with great noise. As an evidence of oft repeated eruptions from Kilauea, the natives remarked to Mr. Bishop, that after rising a little higher the lava would discharge itself towards the sea through some subterranean aperture. Rev. Mr. Stewart visited Kilauea again in October, 1829. The lower pit had been filled up more than two hundred feet, and there was more fire at the northern end. Many of the cones had disappeared, but he was greatly interested in two of them – each one about twenty feet high – tapering from a point above to a base sixty feet in circumference. They were hollow, with steam, vapors and flame issuing from crevices and roaring so as to merit the appellation of "blow holes," or "spiracles," as named by G. Paulett Scrape. Back to Contents Visit of Hiram Bingham Rev. Hiram Bingham spent thirty hours at the volcano October 20th and 21st, 1830. He represented the altitude to be 4,000 feet, ten thousand below Mauna Loa. Six hundred feet below the rim "stretched around horizontally a vast amphitheater gallery of black indurated lava," on which a hundred thousand people might stand. The lake of fire was one thousand feet deep. "The fiercely whizzing sound of gas and steam, rushing with varying force through obstructed apertures in blowing cones, or cooling crusts of lava, the laboring, wheezing struggling, as of a living mountain, breathing fire and smoke and sulphurous gas from his lurid nostrils, tossing up molten rocks or detached portions of fluid lava, and breaking up vast indurated masses with varied detonations, all impressively filled us with awe. "The great extent of the surface of the lava lake; the numerous places on it where the fiery element was displaying itself, the conical mouths here and there, discharging glowing lava over flowing and spreading its waves around, or belched out in detached and molten masses that were shot forth with detonations, perhaps by the force of gases struggling through from below the surface, while the vast column of vapor and smoke ascended up toward heaven ,and the coruscations of the emitted brilliant lava illuminated the clouds that passed over the terrific gulf, all presented by night a splendid and sublime panorama of volcanic action, probably nowhere else surpassed." He descended from the northeast side to the black ledge, and to the lava lake, which "presented cones, mounds, plains, vast bridges of lava recently cooled, pits and caverns, and portions of considerable extent in a movable and agitated state." Near the center is a large mound, from the top of which lava poured out in every direction in a series of circular waves. The outermost wave solidifies, when another one follows, perhaps passing over the first; then others follow as if in a series of pulsations from the "earth's open artery" at the top of the mound. The capillary glass was observed, and its formation understood. "It is formed, I presume, by the tossing off of small detached portions of lava of the consistence of molten glass, from the mouths of cones, when a fine vitreous thread is drawn out between the moving portion and that from which it is detached. The fine spun product is then blown about by the wind, both within and around the crater, and is collected in little locks or tufts." In July, 1831, Mr. Goodrich visited Kilauea and says that "the crater had been filled up to the black ledge, and about fifty feet above it, about nine hundred feet in the whole," since his first visit in 1823. Back to Contents Eruption of 1832 The accounts of the eruption of 1832 are sufficiently full to enable us to know that the disturbances in Kilauea near the lakes of fire correspond to those manifested at other eruptive periods. According to the statements that have already been cited, the lower pit had been filled up with lava to the amount of nine hundred feet since the discharge of 1823. Rev. Joseph Goodrich visited the locality in November and says that the lava "had now again sunk down to nearly the same depth as at first, leaving as usual a boiling caldron at the south end. The inside of the crater had entirely changed. In January – preceding-about the 12th as nearly as I can ascertain – the volcano commenced a vigorous system of operations, sending out volumes of smoke; and the fires so illumined the smoke that it had the appearance of a city enveloped in one general conflagration." A day or two later there were six or eight smart earthquakes, repeated for two or three days. These may have been concerned more particularly with the emissions on the plain between the two craters of Kilauea and Kilauea iki. On descending into the caldera, Mr. Goodrich speaks of the molten lava at the south end – "an opening in the lava sixty to eighty rods long, and twenty or thirty wide." About twenty feet below the brink this liquid mass was "boiling, foaming and dashing in billows against the rocky shore. The mass was in motion, running from north to south at the rate of two or three miles an hour; boiling up as a spring at one end, and running to the other." He speaks of this mass as a lake, and says that the liquid lava is incrusted by its own cooling, just as ice is formed over rivers in cold climates. As the ice in rivers crashes against the shores, so this crust is forced against the bank and distorted. The lava crusts melt and reform while "gaseous matter is forced through, scattering the liquid fire in every direction." There were also two islands in this lake. This, however, must have been after the discharge of the liquid from the bottom of the pit. There is absolutely no testimony from any source, of this eruption, save the statement that it ran away about January 12th. Whether it appeared at the surface, filled up some subterranean cavity or flowed under the sea is entirely unknown. Before its disappearance the lava rose about fifty feet above the black ledge of 1823, thus building up a platform believed to be nine hundred feet above the molten lake. From Mr. Goodrich's statements the depth of the bottom must have been 1,750 feet from the top of the wall. This is confirmed by an entry in the private diary of Rev. W. P. Alexander who visited the volcano January 12, 1833, two months later than Mr. Goodrich, who says the crater was two thousand feet deep. He does not speak of any black ledge; whence it is inferred that this terrace must have been very narrow, as in 1823. Mr. Alexander was disappointed in not finding the principal furnace in lively action while he was at the bottom of the pit; but by the time he had returned to the summit a furious action had commenced and molten lava spouted far into the air with a roaring sound. The following day the boiling caldron was found to be 3,000 feet long, 1,000 wide, and spouting in jets forty or fifty feet high. The manifestations of igneous activity in another part of the area, at this time, January, 1832, as reported by Mr. Goodrich and confirmed by later observations of the effects produced, were unlike any others that have been seen at Kilauea. "The earthquakes rent in twain the walls of the crater on the east side from the top to the bottom, producing seams from a few inches to several yards in width, from which the region around was deluged with lava. The chasms" (were developed) "within a few yards of where Mr. Stewart, Lord Byron, myself and others had slept," the spot being the "Hut" on Malden's map, "so that the spot where I have lain quietly many times is entirely overrun with lava." Back of it, at right angles with the main chasm, and about half way up the precipice, there was a vent a quarter of a mile in length from which the lava issued which had destroyed the Hut. This fissure thus was parallel with the edge of Kilauea Upon Mr. Dodge's map the lava is represented as starting from an orifice below the edge of Poli o Keawe, spreading out like a fan so as to include the Hut, and then turning westerly so as to pour into Kilauea; and there was so much of it that it makes a tongue-like projection into the contour of the lower plain just at the northern end of the sulphur banks. Professor Dana was greatly impressed by the appearance of these cooled and hollow streams, as he saw them in 1840. "The angle of descent of these streams was about thirty-five degrees; and yet the streams were continuous. The ejection had been made to a height of four hundred feet at a time when the pit below was under building lavas and ready for discharge. Elsewhere about the upper walls, and also about those of the lower pit, no scoria was seen. The surfaces of walls are those of fractures, brought into sight by subsidences; and the rocks of the layers were as solid as the most solid of lavas. Moreover, no scoria intervened between the beds of lava even in the walls of the lower pit, each new stream having apparently melted the scoria-crust of the layer it flowed over; and no beds of cinders or volcanic ashes were anywhere to be seen in alternation with the beds of lava. While the cooled lava streams over the bottom were of the smooth-surfaced kind, and would be called pahoehoe, there was the important distinction into streams having the scoria-crust just mentioned, and those having the exterior solid with no separate crust – facts that pointed to some marked difference in conditions of origin." The floor of Kilauea iki is covered by as many as fifty hummocks fifteen or twenty feet high. They arrested the attention of Professor W. H. Pickering in 1905, who conceives them to illustrate the process of construction of Kilauea itself as well as elevations on the surface of the moon. He says, "The surface of the crater floor of Kilauea iki seems to have solidified into a layer six to ten inches in depth and distinct from the portions below it. A liquid core forced up from below raised this surface layer locally, and shattered it into separate pieces like cakes of ice. This core in the case of the smaller craterlets was sometimes only two or three feet in diameter, and could be seen beneath the shattered surface. In one instance its summit seemed to have an almost globular form, five feet in diameter. If the volcanic forces beneath these craterlets had been more intense, it is probable that the issuing lava would have completely destroyed them, forming a series of crater pits into which the lava would have subsequently retreated. In the southwest part of the floor two such pits were found, perhaps fifteen feet in depth by thirty in diameter, down into which a stream of lava had poured, but had solidified without filling them up." Kilauea iki, according to Mr. Dodge's map, is 3,300 feet from east to west and 2,800 feet from north to south, and is seven hundred and forty feet deep, or eight hundred and sixty-seven feet below the Volcano House, from which it is about a mile distant. It is best reached by descending the north wall, making use of ropes in the steepest part of the slope. It is now (1909) encircled by a carriage road from the Volcano House. This was the original name given to it by the natives, iki, meaning little, and was used by Mr. Ellis in his Journal, and by most travelers. Professor Brigham called it Poli o Keawe, and applied the Kilauea iki to Keanakakoi; and was followed by Captain Dutton. On questioning reliable natives in 1883 about the nomenclature, I found that Mr. Ellis was right in his early application of these names, and that the expression Poli o Keawe, signifying the bosom of Keawe, should be applied to the bluff overlooking Kilauea between the two side pits. Keanakakoi was derived from ana, a cave, and koi an axe or adze: meaning a chipping axe cave, because stone implements had been manufactured here in primitive times. The same name is applied to the famous locality for the manufacture of implements situated near the summit of Mauna Kea. On further investigation I have discovered that Professor Brigham has improperly represented that Mr. Goodrich endorsed two names relating to Kilauea. The first is Halemaumau and the second is Poli o Keawe. He has made an abstract of Mr. Goodrich's statement, as partially quoted above, into two sentences amounting to seventy-eight words, including the two geographical names, and has included the whole in quotation marks. Neither of the expressions Halemaumau or Poli o Keawe were used by Mr. Goodrich, although he describes both the localities. Professor Brigham probably did not intend to intimate that Mr. Goodrich used the words indicated. It is worthy of note that for a short time eruptions may have taken place simultaneously from Kilauea and Mokuaweoweo in 1832. The first one commenced action January 12th and the second June 20th. We have, however, no definite statement from any one that the discharge from Kilauea continued as late as to the opening of the fire streams upon Mauna Loa, though it is not improbable. Back to Contents Between 1832 and 1840 The next visit to Kilauea recorded was by Mr. David Douglass in 1834. He found two molten lakes – the more northern three hundred and nineteen yards in diameter; the more southern, 1,190 x 700 yards in extent, and heart-shaped. The larger one occasionally boiled with terrific grandeur, throwing up jets estimated to be from twenty to seventy feet high. “Nearby stood a chimney forty feet high, which occasionally discharged its steam as if all the steam-engines in the world were concentrated in it." Professor Dana says this is a good description of a blowing cone, though this name had not been used so early. Mr. Douglass measured the velocity of the movement in the lava by timing the rapidity of blocks of stone thrown upon the surface of the stream, just as one may estimate the velocity of water by the chips upon the top. This proved to be nearly three and a quarter miles per hour. Mr. Douglass used the barometer to determine the depths of the black ledge and pit. As the mean of two calculations he found the depth from Uwekahuna to the former to be seven hundred and fifteen feet, and to the bottom of the pit 1,077 feet, or three hundred and sixty-two feet below the black ledge. In addition to this he said it was forty-three feet more to the liquid lavas. This proves that there had been a renewal of the lava from the pit in 1832, and his other observations represent that the lower portion was larger and deeper than after the eruption of 1840. Douglass has been discredited because he seemed to have exaggerated the size and activity of Mokuaweoweo in a letter written to Dr. Hooker, dated three days later than the very reasonable account of the phenomena mentioned above. It has been suggested that he wrote the latter under the influence of temporary hallucination. Charles Burnham says the crater was eight hundred feet deep over the whole surface in 1835 with no cones over seventy-five feet high. A very large lake visible from the hut. From the record book June 17, 1881. In August, 1837 – Mr. S. N. Castle of Honolulu visited Kilauea, and reported that the lower pit below the black ledge was nearly filled up, and he also found active cones in all parts of the caldera. In May, 1838 – Captains Chase and Parker visited the volcano and some account of their trip was compiled by E. C. Kelley for the American Journal of Science. The lavas had nearly filled up the lower pit. Over its floor, about four square miles in •extent, there were twenty-six cones, eight of which were throwing out cinders and molten lava. Six small lakes were in evidence. The largest one was probably identical with the later Halemaumau, upon whose surface an island of solid lava "heaved up and down in the liquid mass, and rocked like a ship on a stormy sea." They also noted the oscillations in the heat, so obvious to later visitors. The lake which had been boiling violently became covered by a mass of black scoriae; but this obscuration was temporary, for very soon this crust commenced cracking, black plates floated upon the surface like cakes of ice upon water, and probably disappeared. At the last moment of observation about a quarter of the floor gave way and became a vast pool of liquid lava. An elaborate drawing of the volcano as it seemed at that time accompanies the sketch, prepared by a New York artist, who evidently incorporated into it the features of Vesuvius. It was taken from the south end, shows the great south lake and the floating island, and is of value because it indicates the nearly complete obliteration of the black ledge. In August or September of the same year Count Strzelecki measured the height of the north-northeast wall with a barometer, finding it to be six hundred feet. Nothing is said about the black ledge, whence it may be inferred that it was not visible. Six craters filled with molten lava are mentioned, four of them three or four feet high, one forty feet and the other one hundred and fifty. Five of these had areas of twelve thousand feet each; and the sixth contained nearly a million and had the name of Haumaumau, and was encircled by a wall of scoriae fifty yards high. He said that the lava rose and sunk in all the lakes simultaneously – an observation that has never been confirmed in the later history. The language descriptive of the craters filled with lava might be interpreted to correspond with the occasional manifestation of a lake supported upon a rim consisting of the cooled liquid, as shown particularly in 1894. Like Mr. Douglass Count Strzelecki has given in the Hawaiian Spectator a more extravagant account of Kilauea, besides the reasonable one abridged above from a book upon New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land published seven years later. He was the first author to use the name Hau-mau-mau (Halemaumau). The latest visit to the volcano previous to the great eruption in 1840 was made by Captain John Shepherd, R. N., September 16, 1839. He mentions several cones and small lakes on the floor of the pit on the way to the great lake. The black ledge was "obliterated": there were cones twenty to thirty feet high emitting lava and vapors with loud detonations; and the Great Lake, supposed to be Halemaumau, though incorrectly stated to be on the east side, was a mile and a half long, within a cone a hundred r88 feet high. There was an apparent flow of the liquid from south to north and spray thrown up from thirty to forty feet. Back to Contents The Eruption of 1840 This was the most important of all the discharges from Kilauea since the country has been known to us. Our sources of information are the statements of Rev. Titus Coan, Captain Charles Wilkes and Professor J.D. Dana. None of these gentlemen were on the spot at the time, but obtained their information from good authorities while the phenomena were fresh in mind. Rev. Mr. Coan happened to be absent in Oahu at the time of the eruption. He had visited the volcano before and was familiar with its features; so that he was qualified to test the statements of the natives. The great basin below the black ledge had been filled to overflowing, and as much as fifty feet thickness had accumulated above the platform. The whole area of the pit is represented as an entire sea of ignifluous matter, with waves dashing against the walls sufficiently energetically as to detach great masses of the overhanging rocks. No one dared to approach near the fiery mass. Mr. Coan believed the statements correct, because not a single part of the lava seen after the eruption was like what had been visible before: all had been melted down and recast. It was May 30th when the inhabitants of Puna first observed indications of fire. On the following day the fire greatly augmented. On the third day, June 1st, the lava began to flow off in a northeasterly direction. By the evening of June 3rd the burning river had reached the sea and discharged over a cliff near Nanawale for three weeks. There were slight and repeated shocks of earthquakes near the volcano, for several successive days; but none were noticed at Hilo. The first appearance of the lava was at a small pit about six miles distant from Kilauea, in the forest. The lava rose in this opening about three hundred feet, and then sank down when there was a discharge below. Remnants of this material were observed by Mr. Coan. Then there were other small ejections in fissures nearby. Others appeared, some two or three miles away, and finally upon June 1st began the principal outflow, twenty-seven miles from Kilauea, eleven from the sea, and 1,244 feet above tide water. A further account of the eruption is given in the words of Mr. Coan: “The source of the eruption is in a forest and was not discovered at first, though several foreigners have attempted it.” "From Kilauea to this place the lava flows in a subterranean gallery probably at the depth of a thousand feet, but its course can be distinctly traced all the way, by the rending of the crust of the earth into innumerable fissures and by the emission of smoke, steam and gases. The eruption in this old crater is small, and from this place the stream disappears again for the distance of a mile or two when the lava again gushes up and spreads over an area of about fifty acres. Again it passes underground for two or three miles, when it reappears in another old wooded crater, consuming the forest and partly filling up the basin.” “Once more it disappears, and flowing in a subterranean channel, cracks and breaks the earth, opening fissures from six inches to ten or twelve feet in width, and sometimes splitting the trunk of a tree so exactly that its legs stand astride at the fissure. At some places it is impossible to trace the subterranean stream on account of the impenetrable thicket under which it passes. After flowing underground several miles, perhaps six or eight, it again broke out like an overwhelming flood, and sweeping forest, hamlet, plantation and everything before it, rolled down with resistless energy to the sea, where leaping a precipice of forty or fifty feet, it poured itself in one vast cataract of fire into the deep below, with loud detonations, fearful hissings, and a thousand unearthly and indescribable sounds.” “Imagine to yourself a river of fused minerals, of the breadth and depth of Niagara, and of a deep gory red, falling in one emblazoned sheet, one raging torrent into the ocean.” “The atmosphere in all directions was filled with ashes, spray, gases, etc., while the burning lava as it fell into the water was shivered into millions of minute particles, and being thrown back into the air fell in showers of sand on all the surrounding country. The coast was extended into the sea for a quarter of a mile, and a pretty sand beach and a new cape were formed! Three hills of scoria and sand were also formed in the sea, the lowest about two hundred and the highest about three hundred feet.” "For three weeks this terrific river disgorged itself into the sea with little abatement. Multitudes of fishes were killed, and the waters of the ocean were heated for twenty miles along the coast. The breadth of the stream where it fell into the sea, is about half a mile, but inland it varies from one to four or five miles in width, conforming, like a river, to the fall of the country over which it flowed. The depth of the stream will probably vary from ten to two hundred feet, according to the inequalities of the surface over which it passed. During the flow, night was converted into day on all eastern Hawaii; the light was visible for more than one hundred miles at sea; and at the distance of forty miles fine print could be read at midnight.” "The whole course of the stream from Kilauea to the sea is about forty miles. The ground over which it flowed descends at the rate of one hundred feet to the mile. The crust is now cooled, and may be traversed with care, though scalding steam, pungent gases and smoke are still emitted in many places. In pursuing my way for nearly two days over this mighty smouldering mass, I was more and more impressed at every step with the wonderful scene. Hills had been melted down like wax; ravines and deep valleys had been filled; and majestic forests had disappeared like a feather in the flame. On the outer edge of the lava, where the stream was more shallow and the heat less vehement, and where of course the liquid mass cooled soonest, the trees were mowed down like grass before the scythe, and left charred, crisp, smouldering and only half consumed. There are numerous vertical holes in the lava, almost as smooth as the calibre of a cannon, which represent the trunks of trees; they were too green to burn when the lava flowed around them but succumbed later to subaerial decay.” "During the progress of the descending stream, it would often fall into some fissure, and forcing itself into apertures, and under massive rocks and even hillocks and extended plots of ground, and lifting them from their ancient beds, bear them with all their superincumbent mass of soil, trees, etc., on its viscous and livid bosom, like a raft on the water. When the fused mass was sluggish, it had a gory appearance like clotted blood, and when it was active it resembled fresh and clotted blood mingled and thrown into violent agitation. Sometimes the flowing lava would find a subterranean gallery diverging at right angles from the main channel, and pressing into it would flow off unobserved, till meeting with some obstruction in its dark passage, when, by its expansive force, it would raise the crust of the earth into a domelike hill of fifteen or twenty feet in height, and then bursting this shell, pour itself out in a fiery torrent around. A man who was standing at a considerable distance from the main stream, and intensely gazing on the absorbing scene before him, found himself suddenly raised to the height of ten or fifteen feet above the common level around him, and he had but just time to escape from his dangerous position, when the earth opened where he had stood, and a stream of fire gushed out." Back to Contents