|

by Rev. S. B. Bishop

The President's Endeavor

To Restore The Queen

An extra session of

Congress was held in Washington from August 7th to November 3rd. There

was a general expectation that the President would give to Congress the

results of Mr. Blount's inquiries, and recommend a course of policy

towards Hawaii. But an impenetrable secrecy veiled the whole subject.

Action was deferred until it would be too late for Congress to interfere

during the extra session.

‘

Then the President

opened a new and very remarkable chapter in the history of Hawaii.

During this period of uncertainty, the ex-Queen sent Mr. E. C.

Macfarlane on a secret mission to Washington. Arriving there September

10th, he was granted long and confidential interviews both with Mr.

Blount and the Secretary of State, and thus was enabled to bring back

exclusive information in regard to the secret views of the

Administration.

Late in September the

Hon. Albert S. Willis of Louisville, Kentucky, was summoned to

Washington, where he received his appointment as Envoy Extraordinary and

Minister Plenipotentiary to Hawaii. His credentials were dated September

27th. He was for three weeks in frequent intercourse with the President

and Secretary of State, and became fully possessed of their views, as

well as familiar with the matter of Blount's Report. Mr. Willis had been

in Congress from 1876 to 1886. October 18th, he received his final

instructions, as follows :

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

WASHINGTON, October 18th, 1893

Sir: Supplementing

the general instructions which you have received with regard to your

official duties, it is necessary to communicate to you, in

confidence, special instructions for your guidance in so far as

concerns the relation of the Government of the United States towards

the de facto Government of the Hawaiian Islands.

The President deemed

it his duty to withdraw from the Senate the treaty of annexation

which has been signed by the Secretary of State and the agents of

the Provisional Government, and to dispatch a trusted representative

to Hawaii to impartially investigate the causes of the so-called

revolution and ascertain and report the true situation in those

Islands. This information was needed the better to enable the

President to discharge a delicate and important public duty.

The instructions

given to Mr. Blount, of which you are furnished with a copy, point

out a line of conduct to be observed by him in his official and

personal relations on the Islands, by which you will be guided so

far as they are applicable and not inconsistent with what is herein

contained.

It remains to

acquaint you with the President's conclusions upon the facts

embodied in Mr. Blount's reports and to direct your course, in

accordance therewith.

The Provisional

Government was not established by the Hawaiian people, or with their

consent or acquiescence, nor has it since existed with their

consent. The Queen refused to surrender her powers to the

Provisional Government until convinced that the minister of the

United States had recognized it as the de facto authority, and would

support and defend it with the military force of the United States,

and that resistance would precipitate a bloody conflict with that

force. She was advised and assured by her ministers and by leaders

of the movement for the overthrow of her government, that if she

surrendered under protest her case would afterwards be fairly

considered by the President of the United States. The Queen finally

wisely yielded to the armed forces of the United States then

quartered in Honolulu, relying upon the good faith and honor of the

President, when informed of what had occurred, to undo the action of

the minister and reinstate her and the authority which she claimed

as the constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands.

After a patient

examination of Mr. Blount's report the President is satisfied that

the movement against the Queen, if not instigated, was encouraged

and supported by the representative of this Government at Honolulu;

that he promised in advance to aid her enemies in an effort to

overthrow the Hawaiian Government and set up by force a new

government in the place, and that he kept this promise by causing a

detachment of troops to be landed from the Boston on the 16th of

January, and by recognizing the Provisional Government the next day

when it was too feeble to defend itself, and the Constitutional

Government was able to successfully maintain its authority against

any threatening force other than that of the United States already

landed.

The President has,

therefore, determined that he will not send back to the Senate for

its action thereon the treaty which he withdrew from that body for

further consideration on the 9th day of March last.

On your arrival at

Honolulu you will take advantage of an early opportunity to inform

the Queen of this determination, making known to her the President's

sincere regret that the reprehensible conduct of the American

minister and the unauthorized presence on land of a military force

of the United States obliged her to surrender her sovereignty for

the time being and rely on the justice of this Government to undo

the flagrant wrong.

You will, however,

at the same time inform the Queen that when reinstated the President

expects that she will pursue a magnanimous course by granting full

amnesty to all who participated in the movement against her,

including persons who are or have been officially or otherwise

connected with the Provisional Government, depriving them of no

right or privilege which they enjoyed before the so-called

revolution. All obligations created by the Provisional Government in

due course of administration should be assumed.

Having secured the

Queen's agreement to pursue this wise and humane policy, which it is

believed you will speedily obtain, you will then advise the

executive of the Provisional Government and his ministers of the

President's determination of the question which their action and

that of the Queen devolved upon him, and that they are expected to

promptly relinquish to her her constitutional authority. Should the

Queen decline to pursue the liberal course suggested, or should the

Provisional Government refuse to abide by the President's decision,

you will report the facts and wait further directions.

In carrying out the

general instructions, you will be guided largely by your own good

judgment in dealing with the delicate situation.

I am, etc.,

(Signed) W. Q.

GRESHAM

On the same day Mr.

Gresham addressed an official letter to the President, in which he

endorsed the conclusions of Mr. Blount's Report, and recommended the

restoration of the Queen. This document with the Report, was kept

strictly secret for one month longer, by which time it was fully

expected that Mr. Willis would have successfully executed his mission.

Gresham's letter was given to the press November 10th, and Blount's

report on November 19th, both creating an extraordinary ferment in the

United States.

Admiral Skerrett had

written July 25th to the Secretary of the Navy that "the government they

( the Provisional Government) now give the people is the best that they

ever had. I believe in their eventual success and have implicit faith in

them." On receipt of this, the Secretary reminded him of Blount's

instructions, adding the words: "Protect American citizens and American

property, but do not give aid physical or moral to either party

contending for the Government at Honolulu, Hawaiian Islands." He was

ordered to the China station in October, exchanging places with

Rear-Admiral John Irwin, who arrived at Honolulu, November 6th by the

China.

Mr. Willis arrived at

Honolulu, November 4th. A time had been carefully selected when there

would be an interval of three weeks, during which the Islands would be

cut off from communication with the United States. On the 7th, he

formally presented his credentials to President Dole, in the following

terms:

MR. PRESIDENT :

Mr. Blount, the late

Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of the United

States to your Government, having resigned his office while absent

from his post, I have the honor now to present his letter of recall,

and to express for him his sincere regret that he is unable in

person to make known his continued good wishes in behalf of your

people and his grateful appreciation of the many courtesies of

which, while here, he was the honored recipient.

I desire at the same

time to place in your hands the letter accrediting me as his

successor. In doing this I am directed by the President to give

renewed assurances of the friendship, interest, and hearty good will

which our Government entertains for you and for the people of this

island realm.

Aside from our

geographical proximity and the consequent preponderating commercial

"interests which centre here, the present advanced civilization and

Christianization of your

people, together

with your enlightened codes of law, stand today beneficial monuments

of American zeal, courage and intelligence.

It is not

surprising, therefore, that the United States were the first to

recognize the independence of the Hawaiian Islands and to welcome

them into, the great family of free nations.

The letter of credence

was as follows:

GROVER CLEVELAND,

President of the United States of America

To His Excellency

SANFORD B. DOLE, President of the Provisional Government of the

Hawaiian Islands

GREAT AND GOOD

FRIEND:

I have made choice

of Albert S. Willis, one of our distinguished citizens, to reside

near the government of your excellency in the quality of Envoy

Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary of the United States of

America. He is well informed of the relative interests of the two

countries and of our sincere desire to cultivate, to the fullest

extent, the friendship which has so long subsisted between us. My

knowledge of his high character and ability gives me entire

confidence that he will constantly endeavor to advance the interests

and prosperity of both governments, and so render himself acceptable

to your excellency.

I therefore request

your excellency to receive him favorably and to give full credence

to what he shall say on the part of the United States, and to the

assurances which I have charged him to convey to you of the best

wishes of this Government for the prosperity of the Hawaiian

Islands. May

God have your excellency in His wise keeping.

Written at

Washington, this 27th day of September, in the year 1893

Your good friend,

(Signed) GROVER

CLEVELAND

President Dole responded

in a cordial strain. The friendly tone of this language tended to lull

apprehensions which had been felt of a possibly hostile errand of, the

new Minister. The royalists were otherwise informed, and their organs

insisted that Mr. Willis had come to enforce by arms a demand for the

Provisional Government to abdicate in favor of Liliuokalani. No

intimation of such action found its way to the American press. British

agents were better informed, and a London telegram reached Auckland, N.

Z., November 2nd, and Honolulu, November 16th, that " the President was

drafting a message to Congress in favor of restoring monarchy to

Hawaii." This was the first intimation received in Honolulu of the

President's intentions. It was generally discredited. The British

cruiser Champion, Capt. Rooke, arrived 'at Honolulu, November 24th, and

the Japanese cruiser Naniwa, December 2nd.

Mr.

Willis Negotiates with the ex-Queen

Already had Mr. Willis

begun the execution of his mission, but at the outset found his action

obstructed by an unforeseen obstacle. The ex-Queen firmly refused to

concede amnesty to her opponents, as an indispensable preliminary to her

restoration. By his request, the ex-Queen visited the Minister at the

Legation on the 13th of November, and a short but important private

interview ensued, as follows :

LEGATION OF THE

UNITED STATES, HONOLULU, Nov. 16th, 1893

MR. WILLIS TO MR.

GRESHAM

Sir: In the forenoon

of Monday, the 13th instant, by prearrangement, the Queen,

accompanied by the royal chamberlain, Mr. Robertson, called at the

Legation. No one was present at the half-hour interview which

followed, her chamberlain having been taken to another room, and

Consul-General Mills, who had invited her to come, remaining in the

front of the house to prevent interruption.

After a formal

greeting, the Queen was informed that the President of the United

States had important communications to make to her and she was asked

whether she was willing to receive them alone and in confidence,

assuring her that this was for her own interest and safety. She

answered in the affirmative.

I then made known to

her the President's sincere regret that, through the unauthorized

intervention of the United States, she had been obliged to surrender

her sovereignty, and his hope that, with her consent and

cooperation, the wrong done to her and to her people might be

redressed. To this, she bowed her acknowledgments.

I then said to her,

"The President expects and believes that when reinstated you will

show forgiveness and magnanimity; that you will wish to be the Queen

of all the people, both native and foreign born; that you will make

haste to secure their love and loyalty and to establish peace,

friendship, and good government." To this she made no reply. After

waiting a moment, I continued: "The President not only tenders you

his sympathy but wishes to help you. Before fully making known to

you his purposes, I desire to know whether you are willing to answer

certain questions which it is my duty to ask?" She answered, "I am

willing." I then asked her, "Should you be restored to the throne,

would you grant full amnesty as to life and property to all those

persons who have been or who are now in the Provisional Government,

or who have been instrumental in the overthrow of your government?"

She hesitated a moment and then slowly and calmly answered: "There

are certain laws of my Government by which I shall abide. My

decision would be, as the law directs, that such persons should be

beheaded and their property confiscated to the Government." I then

said, repeating very distinctly her words, "

It is your feeling

that these people should be beheaded and their property

confiscated?" She replied, "It is." I then said to her, " Do you

full}7 understand the meaning of every word which I have said to

you, and of every word which you have said to me, and, if so, do you

still have the same opinion?" Her answer was, "I have understood and

mean all I have said, hut I might leave the decision of this to my

ministers." To this I replied, '' Suppose it was necessary to make a

decision before you appointed any ministers, and that you were asked

to issue a royal proclamation of general amnesty, would you do it?"

She answered, "I have no legal right to do that, and I would not do

it." Pausing a moment she continued. "These people were the cause of

the revolution and constitution of 1887. There will never be any

peace while they are here. They must be sent out of the country, or

punished, and their property confiscated." I then said, "I have no

further communication to make to you now, and will have none until I

hear from my Government, which will probably be three or four

weeks."

Nothing was said for

several minutes, when I asked her whether she was willing to give me

the names of four of her most trusted friends, as I might, within a

day or two, consider it my duty to hold a consultation with them in

her presence. She assented, and gave these names: J. O. Carter, John

Richardson, Joseph Nawahi and E. C. Macfarlane. I then inquired

whether she had any fears for her safety, at her present residence,

Washington Square. She replied that she did have some fears, that

while she had trusty friends that guarded her house every night,

they were armed only with clubs, and that men shabbily dressed had

been often seen prowling about the adjoining premises a schoolhouse

with large yard. I informed her that I was authorized by the

President to offer her protection either on one of our "war ships or

at the legation and desired her to accept the offer at once. She

declined, saying she believed it was best for her at present to

remain at her own residence. I then said to her that at any moment,

night or day, this offer of our Government was open to her

acceptance. The interview thereupon, after some personal remarks,

was brought to a close.

Upon reflection, I

concluded not to hold any consultation at present with the Queen's

friends, as they have no official position, and furthermore, because

I feared, if known to so many, her declarations might become public,

to her great detriment, if not danger, and to the interruption of

the plans of our Government.

Mr. J. O. Carter is

a brother of Mr. H. A. P. Carter, the former Hawaiian Minister to

the United States, and is conceded to be a man of high character,

integrity, and intelligence. He is about 55 years old. He has had no

public experience. Mr. Macfarlane, like Mr. Carter, is of white

parentage, is an unmarried man, about 42 years old, and is engaged

in the commission business. John Richardson is a young man of about

35 years old. He is a cousin of Samuel Parker, the half-caste, who

was a member of the Queen's cabinet at the time of the last

revolution. He is a resident of Maui, being designated in the

directory of 1889 as "attorney at law, stock-raiser, and proprietor

Bismark livery stable." Richardson is "half-caste." Joseph Nawahi is

a full-blooded native, practices law (as he told me) in the native

courts, and has a moderate English education. He has served twenty

years in the legislature, but displays very little knowledge of the

structure and philosophy of the Government which he so long

represented. He is 51 years old, and is president of the native

Hawaiian political club.

Upon being asked to

name three of the most prominent native leaders, he gave the names

of John E. Bush, R. W. Wilcox, and modestly added, "I am a leader."

John E. Bush is a man of considerable ability, but his reputation is

very bad. R. W. Wilcox is the notorious half-breed who engineered

the revolution of 1889. Of all these men Carter and Macfarlane are

the only two to whom the ministerial bureaus could be safely

entrusted. In conversation with Sam Parker, and also with Joseph

Nawahi, it was plainly evident that the Queen's implied condemnation

of the constitution of 1887 was fully indorsed by them.

From these and other

facts which have been developed, I feel satisfied that there will be

a concerted movement in the event of restoration for the overthrow

of that constitution, which would mean the overthrow of

constitutional and limited government and the absolute dominion of

the Queen. The law referred to by the Queen is Chapter VI, Section 9

of the Penal Code, as follows :

"Whoever shall

commit the crime of treason shall suffer the punishment of death,

and all his property shall be confiscated to the Government."

There are, under

this law, no degrees of treason. Plotting alone carries with it the

death sentence. I need hardly add, in conclusion, that the tension

of feeling is so great that the promptest action is necessary to

prevent disastrous consequences.

I send a cipher

telegram asking that Mr. Blount's report be withheld for the

present, and I send with it a telegram, not in cipher, as follows :

"Views of the first

party so extreme as to require further instructions."

I am, etc.

(Signed) ALBERT S.

WILLIS

In reporting the

foregoing interview, Mr. Willis suggested to Mr. Gresham that "Blount's

report be withheld from the public for the present" a measure of

prudence advised too late. The Auckland telegram led to influential

persons making earnest inquiries of the Minister as to his intentions.

He replied that "no

change would take place for some time. Unforeseen contingencies had

arisen, and farther communication with Washington must be had before any

thing could be done." Great speculation at once arose as to the nature

of the "contingencies" spoken of. No one guessed the truth. The

disturbance and excitement of the public mind daily increased. The

Government perfected the defenses of the Executive and Judiciary

buildings. The volunteer forces were increased and improved in

organization and equipment.

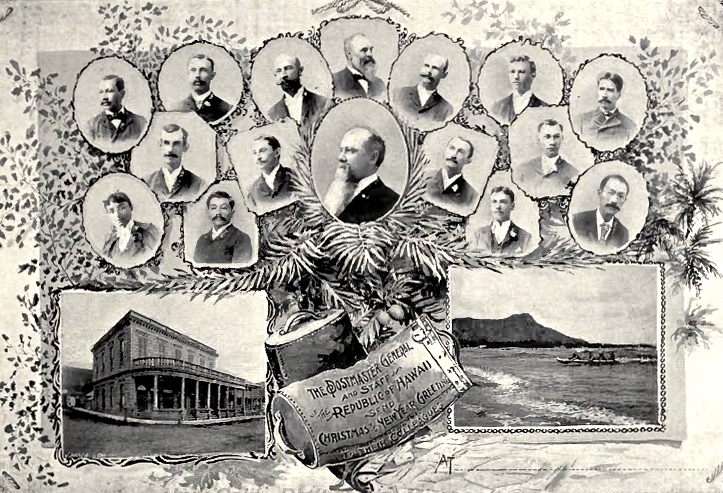

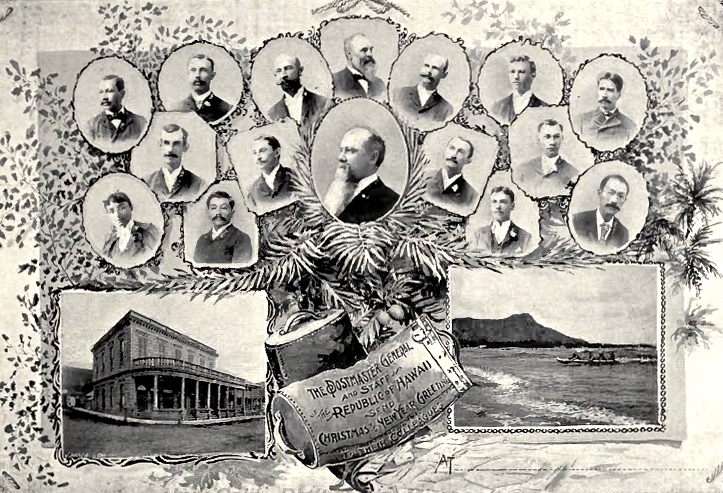

H. A. Widemann, J. O.

Carter,

W. Macfarlane, C. Spreckles, E. C.

Macfarlane

By the Monowai, November

24th, came Gresham's letter to the President, urging "the restoration of

the legitimate government " of Hawaii, on the ground of facts

established by Blount's report. On the evening of the 25th, a very large

and enthusiastic mass meeting was held in the drill shed.

Several speeches were

made by prominent men, counselling resistance to the utmost. The first

address was by Vice-President F. M. Hatch, who made a cogent argument to

show that no such arbitration as Gresham alleged had ever been or could

be held by the President, nor could his decision have any force. The

following resolutions were adopted by the assembly:

"Resolved, That we

have read with surprise and regret the recommendation of the

Secretary of State of the United States to the President, to restore

the monarchy lately existing in Hawaii.

Resolved, That we

condemn the assumption of the Secretary that the right of the

Provisional Government to exist was terminated by his refusal to

re-submit to the Senate the treaty of Union pending between the two

countries; and also his assumption that the Provisional Government

had at that very time submitted the question of its continued

existence to the arbitrament of the President or of any other power.

Resolved, That we

support to the best of our ability the Provisional Government, in

resisting any attack upon it which may be made contrary to the usage

of nations."

On November 29th,

President Dole addressed to Minister Willis the inquiry whether the

press report of Gresham's letter was correct, and what were the

intentions of the United States Government towards that of Hawaii? On

December 2nd, Mr. Willis replied that Gresham's letter "was in the

nature of a report to the President of the United States, and could only

be regarded as a domestic matter, for which the American Minister to

Hawaii was in no way responsible, and which he could not assume to

interpret." He also declined to inform President Dole of the views or

intentions of the United States Government. He had, however, assured

various persons that no action would be taken until an answer was

received to his dispatch of November 16th, which would not be due until

the arrival of the regular mail steamer of December 21st. This assurance

served to allay the public apprehensions, as it was most confidently

expected that before that date Congress would effectively interpose to

arrest the President's proceedings.

At Washington, in the

meantime, the Hawaiian Minister, L. A. Thurston, on November 21st, made

a sharp and cogent reply to Blount's attack upon himself, and exposed

the fallacy of his main position, that "but for the support of the

United States representative and troops the establishment of the

Provisional Government would have been impossible."

In the interim, Minister

Willis held occasional conferences with leading adherents of the Queen,

apparently in order to inform himself as to their characters and

opinions. On December 5th, the ex-marshal, C. B. Wilson, called on Mr.

Willis, and submitted a lengthy programme of proposed procedure to

accompany the Queen's restoration. This he said had been submitted to

leading advisers of the Queen, and had met their approval. It included a

series of measures of great severity towards all concerned in

establishing the Provisional Government.

Wilson also submitted a

long list of "tried and trusted friends of the monarchy and the nation"

who should form a council to aid the Queen in carrying out the proposed

measures and in re-establishing herself upon the throne. Upon this list

Mr. Willis made the following comment: "An analysis of the list of

special advisers, whether native or foreign, is not encouraging to the

friends of good government, or of American interests. This is true, both

of the special list of advisers, and of the supplementary list. The

Americans who for over half a century held a commanding place in the

councils of state, are ignored, and other nationalities, English

especially, are placed in charge." Herein Mr. Willis showed himself

sufficiently American to recognize considerations which Mr. Blount had

totally ignored. Congress assembled on December 4th, for its regular

session. The President's message of that date contained only a brief and

indefinite statement concerning Hawaii, the essential part of which was

as follows:

"Our only honorable

course was to undo the wrong that had been done by those

representing us, and to restore as far as practicable the status

existing at the time of our forcible intervention. Our present

Minister has received appropriate instructions to that end."

This was the first

positive information published anywhere as to the orders of Minister

Willis. It reached Honolulu on the 14th of December, by the U. S.

Revenue cutter Corwin, which had been secretly dispatched on the same

day as the Message, with orders to Minister Willis as follows :

DEPARTMENT OF STATE,

WASHINGTON, December 3d, 1893

MR. GRESHAM TO MR.

WILLIS.

Your dispatch, which

was answered by steamer on the 25th of November, seems to call for

additional instructions. Should the Queen refuse assent to the

written conditions, you will at once inform her that the President

will cease interposition in her behalf, and that while he deems it

his duty to endeavor to restore to the sovereign the constitutional

government of the islands, his further efforts in that direction

will depend upon the Queen's unqualified agreement that all

obligations created by the Provisional Government in a proper course

of administration shall be assumed, and upon such pledges by her as

will prevent the adoption of any measures of proscription or

punishment for what has been done in the past by those setting up or

supporting the Provisional Government. The President feels that by

our original interference and what followed, we have incurred

responsibilities to the whole Hawaiian community, and it would not

be just to put one party at the mercy of the other.

Should the Queen ask

whether if she accedes to conditions active steps will be taken by

the United States to effect her restoration, or to maintain her

authority thereafter, you will say that the President can not use

force without the authority of Congress.

Should the Queen

accept conditions and the Provisional Government refuse to

surrender, you will be governed by previous instructions. If the

Provisional Government asks whether the United States will hold the

Queen to fulfillment of stipulated conditions you will say, the

President acting under dictates of honor and duty, as he has done in

endeavoring to effect restoration, will do all in his constitutional

power to cause observance of the conditions he has imposed.

(Signed) GRESHAM

The Corwin was not

allowed to bring any mail matter, but a newspaper containing the

President's melange happened to be on board.

Minister Thurston at

Washington, on the day after the President's message, addressed to

Secretary Gresham a vigorous protest against the President's assumption

of authority or jurisdiction to restore the Queen or in any way to

interfere with the Government of Hawaii. He also sought in an interview

with the Secretary to learn whether Minister Willis had been empowered

to employ force in restoring the Queen. The Secretary was diplomatic,

but left the impression upon Mr. Thurston's mind that such force was not

to be used.

The attacks upon the

President's action continued in Congress and in the public press with

increasing severity. Resolutions were speedily passed by both Houses,

requesting full information on Hawaiian affairs. On the 18th of

December, President Cleveland sent to Congress a special message upon

the Hawaiian question, commending this subject to their "extended powers

and wide discretion." At that moment the business was reaching its

crisis at Honolulu.

The essential part of

the message is as follows :

To THE SENATE AND

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES:

"In my recent annual

message to the Congress, I briefly referred to our relations with

Hawaii, and expressed the intention of transmitting further

information on the subject when additional advices permitted.

Though I am not able

now to report a definite change in the actual situation, I am

convinced that the difficulties lately created both here, and

in Hawaii, and now standing in the way of a solution through

executive action of the problem presented, render it proper and

expedient that the matter should be referred to the broader

authority and discretion of Congress, with a full explanation of the

endeavor thus far made to deal with the emergency, and a statement

of the considerations which have governed my action."

After an extended

statement, based entirely on Col. Blount's report, the President

continued as follows:

DECEMBER 18th, 1893.

"I believe that a

candid and thorough examination of the facts will force the

conviction that the Provisional Government owes its existence to an

armed invasion by the United States.

A substantial wrong

has thus been done which a due regard for our national character as

well as the rights of the injured people requires that we should

endeavor to repair.

Actuated by these

desires and purposes and not unmindful of the inherent perplexities

of the situation nor of the limitation upon my power, I instructed

Minister Willis to advise the Queen and her supporters of my desire

to aid in the restoration of the status existing before the lawless

landing of the United States forces at Honolulu on the 16th of

January last, if such restoration could be effected upon terms

providing for clemency as well as justice to all parties concerned.

The conditions suggested, as the instructions show, contemplate a

general amnesty to those concerned in setting up the Provisional

Government and a recognition of all its bona fide acts and

obligations.

In short, they

require that the past should be buried, and that the restored

government should reassume its authority as if its continuity had

not been interrupted. These conditions have not proved acceptable to

the Queen, and though she has been informed that they will be

insisted upon and that, unless acceded to, the efforts of the

President to aid in the restoration of her government will cease, I

have not thus far learned that she is willing to yield them her

acquiescence. The check which my plans have thus encountered has

prevented their presentation to the members of the Provisional

Government, while unfortunate public misrepresentations of the

situation and exaggerated statements of the sentiments of our people

have obviously injured the prospects of successful executive

mediation.

I therefore submit

this communication with its accompanying exhibits, embracing Mr.

Blount's report, the evidence and statements taken by him at

Honolulu, the instructions given to both Mr. Blount and Minister

Willis, and the correspondence connected with the affair in hand.

In commending this

subject to the extended powers and of wide discretion of the

Congress, I desire, to add the assurance that I shall be much

gratified to cooperate in any legislative plan which may he devised

for the solution of the problem before us, which is consistent with

American honor, integrity and morality."

(Signed) GROVER

CLEVELAND

The

"Black Week" in Honolulu

The unexpected arrival

of the Corwin in the early morning of the 14th created intense

excitement and consternation, beginning a seven days of severest anxiety

and apprehension. A demand for the restoration of the deposed Queen was

daily expected from the American Minister. It was believed by all

parties that this demand would be supported by the naval forces of the

warships Philadelphia and Adams, under the command of Admiral Irwin. The

forces of those ships were immediately prepared and held in hourly

readiness for landing. It was evident that the President had arranged to

be beforehand with any possible interference by Congress with his

designs. The supporters of the Government were fully prepared to resist

to the utmost the attack of the United States forces. Battle was

expected at any hour, and the strain and tension grew daily more severe.

This state of things is described in detail in President Dole's letter

of specifications to Minister Willis, of January 11th, 1894. It was

subsequently proved that the coming demand was not intended to be

supported by the actual use of force, but only by an exhibition thereof.

Renewed Efforts to Mollify Royalty

On the 16th, two days

after the arrival of the Corwin, the ex-Queen came by previous

appointment to the legation at 9 A. M., accompanied by Mr. J. O. Carter

as adviser. Mr. Willis said, "The President expects and believes that

when reinstated you will show forgiveness and magnanimity." Reading over

his report of their interview of November 13th, he asked if her views

were now in any respect modified. The only concession she would make was

to remit the capital punishment of her opponents, but they and their

families must be deported, and their property confiscated.

"Their presence and that

of their children would always be a dangerous menace to herself and her

people."

She also insisted on

being reinstated with a new Constitution similar to the one she had

attempted to promulgate. She agreed to accept responsibility for the

obligations of the Provisional Government, their military expenses to be

refunded to the treasury out of their confiscated estates.

On Monday the 18th, at

Mr. Carter's solicitation, another interview was accorded to

Liliuokalani. This took place at her residence in Washington Place, in

the afternoon, Mr. Carter being present with Consul Mills as

stenographer. Mr. Carter made an address, in which he urged her to

comply - that good government seemed impossible unless Her Majesty

showed a spirit of forgiveness and magnanimity - that the movement

against her and her people embraced a a large and respectable portion of

the foreign element in this community, which could not be ignored.

The ex-Queen expressed

herself as feeling that any third attempt at revolution on the part of

those people would be very destructive to life and property; that her

people had had about all they could stand of this interference with

their rights. She continued explicitly to define her intention that

their property should be confiscated.

Mr. Willis made it clear

that the President would insist upon complete amnesty and the old

Constitution. She asked how she should know that in the future the

country should not be troubled again as it had been in the past.

The Minister replied

that the United States had no right to look into that subject or to

express an opinion upon it.

The interview

terminated, and after the report thereof had been duly attested, Mr.

Mills informed the ex-Queen that the two reports of the 16th and 18th

would be immediately forwarded to the President, and his answer when

received would be promptly made known to her. By the minister's orders,

the Corwin was put in readiness to sail that evening with his

dispatches.

All that morning of the

18th there had been increased stir of preparation on board of the

Philadelphia and the Adams. Crowds of natives thronged the wharves in

expectation of an immediate landing of the naval forces to restore the

Queen. A majority of the native policemen that morning threw up their

positions, rather than take a required oath to support the Government.

Intense alarm pervaded the city all that day.

Mr. H. F. Glade, consul

for Germany called that morning upon Mr. Willis -and asked him to say

something to allay the extreme tension of alarm which was paralyzing all

business and filling the people with terror. The Minister replied that

he was unable to say anything - that he was laboring to the utmost to

secure a result satisfactory to all parties, but did not expect to

attain that end under forty-eight hours.

The supporters of the

Government had in the mean time given the Executive the strongest

assurance of their desire and readiness to resist to the death the

United States forces in any attempt to restore the Queen. The Government

had at first felt hesitation in proposing to Americans to fire upon

their own flag. The urgent appeals of American citizens, however,

determined the Government to resist to the last, and arrangements were

made accordingly. It was well that the ex-Queen's desires to behead and

deport her opponents had been kept secret. Farther exasperation would

have been dangerous.

Mr.

Carter's Successful Mediation

In his repeated

intercourse during the day with the ex-Queen, the Minister was imagined

to be formulating the re-organization of her government. It was not

imagined that she was resisting a demand for amnesty. She continued to

be obdurate. The dispatches reporting her final refusal of the terms

were ready to go to the Corwin. Seeing this to be her last opportunity,

her faithful friend, Mr. J. O. Carter, a man of conscientious character,

again went to her and labored with her with such success that at 6 p. M.

he was enabled to carry to Mr. Willis a written assurance that she would

comply with all his conditions. The Corwin's sailing was countermanded.

No one has questioned

the integrity of Mr. Carter's intentions. But after Liliuokalani's

extreme attitude became known about beheading and confiscation, a strong

feeling arose against him for having labored so zealously to secure her

restoration, after having learned her disposition. The animosity became

so strong among Mr. Carter's former near associates who had been marked

as her victims, that he was displaced from a responsible and lucrative

business position. President Dole had that afternoon addressed to Mr.

Willis the following letter:

DEPARTMENT OF

FOREIGN AFFAIRS, HONOLULU, HAWAIIAN ISLANDS, Dec. 18th, 1893

Sir: I am informed

that you are in communication with Liliuokalani, the ex-Queen, with

a view of re-establishing the monarchy in the Hawaiian Islands and

of supporting her pretensions to the sovereignty. Will you inform me

if this report is true or if you are acting in any way hostile to

this Government.

I appreciate fully

the fact that any such action upon your part in view of your

official relations with this Government would seem impossible; but

as the information has come to me from such sources that I am

compelled to notice it, you will pardon me for pressing you for an

immediate answer.

Accept the

assurances of distinguished consideration with which I have the

honor to be sir,

Your excellency's

obedient, humble servant,

(Signed) SANFORD B.

DOLE, Minister of Foreign Affairs

Mr. Willis replied next

morning as follows:

LEGATION OF THE

UNITED STATES, HONOLULU, Dec. 19th, 1893

Sir: I have the

honor to inform you that I have a communication from my Government

which I desire to submit to the President and ministers of your

Government at any hour today which it may please you to designate.

With high regard and

sincere respect, I am, etc.,

(Signed) ALBERT S.

WILLIS

The

Demand for the Queen's Restoration

At 9:30 A. M., of the 19th, Mr. Carter

brought to Mr. Willis the ex-Queen's fully expressed agreement to all

his conditions. At 1:30 P. M., the American Minister met the President

and Executive Council at the Foreign Office, and read to them the

following communication:

Mr. PRESIDENT AND GENTLEMEN:

The President of the United States

has very much regretted the delay in the consideration of the

Hawaiian question, but it has been unavoidable. So much of it as has

occurred since my arrival has been due to certain

conditions precedent, compliance with which was required before I

was authorized to confer with you. The President also regrets, as

most assuredly do I, that any seeming secrecy should have surrounded

the interchange of views between our two Governments. I may say

this, however, that the secrecy thus far observed, has been in the

interest and for the safety of all your people.

I need hardly promise that the

President's action upon the Hawaiian question has been under the

dictates of honor and duty. It is now, and has been from the

beginning, absolutely free from prejudice and resentment, and

entirely consistent with the long-established friendship and treaty

ties which have so closely bound together our respective

Governments.

The President deemed it his duty to

withdraw from the Senate the treaty of annexation which had been

signed by the Secretary of State and the agents of your Government,

and to dispatch a trusted representative to Hawaii to impartially

investigate the causes of your revolution, and ascertain and report

the true situation in these islands. This information was needed,

the better to enable the President to discharge a delicate and

important duty. Upon the facts embodied in Mr. Blount's reports, the

President has arrived at certain conclusions and determined upon a

certain course of action with which it becomes my duty to acquaint you.

The Provisional Government was not

established by the Hawaiian people or with their consent or

acquiescence, nor has it since existed with their consent. The Queen

refused to surrender her powers to the Provisional Government until

convinced that the Minister of the United States had recognized it

as the de facto authority and would support and defend it with the

military force of the United States, and that resistance would

precipitate a bloody conflict with that force. She was advised and

assured by her ministers and by leaders of the movement for the

overthrow of her Government that if she surrendered under protest

her case would afterwards be fairly considered by the President of

the United States. The Queen finally yielded to the armed forces of

the United States then quartered in Honolulu, relying on the good

faith and honor of the President, when informed of what had

occurred, to undo the action of the Minister and reinstate her and

the authority which she claimed as the constitutional sovereign of

the Hawaiian Islands.

After a patient

examination of Mr. Blount's reports the President is satisfied that

the movement against the Queen, if not instigated, was encouraged

and supported by the representative of this Government at Honolulu ;

that he promised in advance to aid her enemies in an effort to

overthrow the Hawaiian Government and set up by force a new

government in its place, and that he kept this promise by causing a

detachment of troops to be landed from the Boston on the 16th of

January, and by recognizing the Provisional Government the next day

when it was too feeble to defend itself and the Constitutional

Government was able to successfully maintain its authority against

any threatening force other than that of the United States already

landed.

The President has

therefore determined that he will not send back to the Senate for

its action thereon the treaty which he withdrew from that body for

further consideration on the 9th day of March last.

In view of these

conclusions, I was instructed by the President to take advantage of

an early opportunity to inform the Queen of this

determination and of his views as to the responsibility of our

Government.

The President,

however, felt that "we, by our original

interference, had incurred

responsibilities to the whole Hawaiian community, and that it would

not be just to put one party at the mercy of the other. I was,

therefore, instructed, at the same time, to inform the Queen that

when

reinstated, that the President expected that she would pursue a

magnanimous course by granting fully amnesty to all who participated

in the movement against her, including persons who are or who have

been officially or otherwise connected with the Provisional

Government, depriving them of no right or privilege which they

enjoyed before the so-culled revolution. All obligations created by

the Provisional Government in due course of administration should be

assumed. In obedience to the command of the President I have secured

the Queen's agreement to this course, and I -now read and deliver a

writing signed by her and duly attested, a copy of which I will

leave with you.

(The agreement was

here read.)

It becomes my

further duty to advise you, sir, the executive of the Provisional

Government and your ministers, of the President's determination of

the question, which your action and that of the Queen devolved upon

him, and that you are expected to promptly relinquish to her

constitutional authority.

And now, Mr.

President, and gentlemen of the Provisional Government, with a deep

and solemn sense of the gravity of the situation and with the

earnest hope that your answer will be inspired by that high

patriotism which forgets all self-interest, in the name and by the

authority of the United States of America, I submit to you the

question, "Are you willing to abide by the decision of the

President?"

The Advisory Council

were immediately summoned to conference. With the utmost promptness and

unanimity, both councils voted to instruct President Dole to refuse

compliance with the extraordinary demand of Mr. Willis in such terms as

should be most fitting.

As the minister's demand

was not accompanied with any threat of coercion, as the action of the

Government was decided, as the preparation of a suitable reply would

occupy some days, and as the Alameda was due in two days with probable

news of the vigorous intervention of Congress to prevent forcible

coercion, there was a material relaxation of the tension which had been

felt for several days. The extreme crisis was past.

The Alameda arrived on

Friday the 22d. The eight days of anxiety came to an end. Congress had

powerfully intervened. The Senate had solemnly arraigned the President

for unconstitutional behavior. Messrs. L. A. Thurston, W. N. Armstrong

and H. N. Castle arrived. The word was passed ashore "All is right," and

swiftly sped up the streets at sunrise. Honolulu's "Black Week" was

over.

Dole's

Reply to Willis' Demand

On the evening of the

23d of December, the completed reply of President Dole to the strange

demand of the American Minister was placed in the hands of Mr. Willis.

The Minister's dispatches were completed and the Corwin sailed at 4 A.

M. of the 24th. She was not allowed to take any mail, public or private.

She was ordered by Mr. Willis to slow up, and enter the bay of San

Francisco at night, in order to enable the President to receive this

official communication before any intimation of its character could be

telegraphed. For several days after she was anchored out in the bay, and

no communication allowed with the shore.

Mr. Willis' precautions

were successful, and the American public for several days gained no

knowledge of the strange doings at Honolulu until January 9th.

Mr. Dole's reply was as

follows :

DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN

AFFAIRS, HONOLULU, December 23d, 1893

Sir: Your excellency's

communication of December 19th, announcing the conclusion which the

President of the United States of America has finally arrived at

respecting the application of this Government for a treaty of political

union with that country, and referring also to the domestic affairs of

these islands, has had the consideration of the Government.

While it is with deep

disappointment that we learn that the important proposition which we

have submitted to the Government of the United States, and which was at

first favorably considered by it, has at length been rejected, we have

experienced a sense of relief that we are now favored with the first

official information upon the subject that has been received through a

period of over nine months.

While we accept the

decision of the President of the United States, declining further to

consider the annexation proposition, as the final conclusion of the

present administration, we do not feel inclined to regard it as the last

word of the American Government upon this subject, for the history of

the mutual relations of the two countries, of American effort and

influence in building up the Christian civilization which has so

conspicuously aided in giving this country an honorable place among

independent nations, the geographical position of these islands, and the

important and, to both countries, profitable reciprocal commercial

interests which have long existed, together with our weakness as a

sovereign nation, all point with convincing force to political union

between the two countries as the necessary logical result from the

circumstances mentioned. The conviction is emphasized by the favorable

expression of American statesmen over a long period in favor of

annexation, conspicuous among whom are the names of W. L. Marcy, William

H. Seward, Hamilton Fish, and James G. Elaine, all former Secretaries of

State, and especially so by the action of your last administration in

negotiating a treaty of annexation with this Government and sending it

to the Senate with a view to its ratification.

We shall therefore

continue the project of political union with the United States as a

conspicuous feature of our foreign policy, confidently hoping that

sooner or later it will be crowned with success, to the lasting benefit

of both countries.

The additional portion

of your communication referring to our domestic affairs with a view of

interfering therein, is a new departure in the relations of the two

governments.

Your information that

the President of the United States expects this Government "to promptly

relinquish to her (meaning the ex-Queen) her constitutional authority,"

with the question "are you willing to abide by the decision of the

President?" might well be dismissed in a single word, but for the

circumstance that your communication contains, as it appears to me,

misstatements and erroneous conclusions based thereon, that are so

prejudicial to this Government that I can not permit them to pass

unchallenged; moreover, the importance and menacing character of this

proposition make it appropriate for me to discuss somewhat fully the

question raised by it.

We do not recognize the

right of the President of the United States to interfere in our domestic

affairs. Such right could be conferred upon him by the act of this

government, and by that alone, or it could be acquired by conquest. This

I understand to be the American doctrine, conspicuously announced from

time to time by the authorities of your Government.

President Jackson said

in his message to Congress in 1836: "The uniform policy and practice of

the United States is to avoid all interference in disputes which merely

relate to the internal government of other nations, and eventually to

recognize the authority of the prevailing party, without reference to

the merits of the original controversy."

This principle of

international law has been consistently recognized during the whole past

intercourse of the two countries, and was recently reaffirmed in the

instructions given by Secretary Gresham to Commissioner Blount on March

11, 1893, and by the latter published in the newspapers in Honolulu in a

letter of his own to the Hawaiian public. The words of these

instructions which I refer to are as follows :

"The United States claim

no right to interfere in the political or domestic affairs or in the

internal conflicts of the Hawaiian Islands other than as herein stated

(referring to the protection of American citizens) or for the purpose of

maintaining any treaty or other rights which they possess." The treaties

between the two countries confer no right of interference.

Upon what, then, Mr.

Minister, does the President of the United States base his right of

interference? Your communication is without information upon this point,

excepting such as may be contained in the following brief and vague

sentences: "She (the ex-Queen) was advised and assured by her ministers

and leaders of the movement for the overthrow of her government that if

she surrendered under protest her case would afterward be fairly

considered by the President of the United States. The Queen finally

yielded to the armed forces of the United States, then quartered in

Honolulu, relying on the good faith and honor of the President, when

informed of what had occurred, to undo the action of the minister and

reinstate her and the authority which she claimed as the constitutional

sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands."

Also, "it becomes my

further duty to advise you, sir, the Executive of the Provisional

Government, and your ministers; of the President's determination of the

question which your action and that of the Queen devolved upon him, and

that you are expected to promptly relinquish to her constitutional

authority."

I understand that the

first quotation is referred to in the following words of the second,

"which your action and that of the Queen devolved upon him" (the

President of the United States), and that the President has arrived at

his conclusions from Commissioner Blount's report. We have had as yet no

opportunity of examining this document, but from extracts published in

the papers and for reasons set forth hereafter, we are not disposed to

submit the fate of Hawaii to its statements and conclusions. As a matter

of fact no member of the executive of the Provisional Government has

conferred with the ex-Queen, either verbally or otherwise, from the time

the new Government was proclaimed till now, with the exception of one or

two notices which were sent to her by myself in regard to her removal

from the palace and relating to the guards which the Government first

allowed her and perhaps others of a like nature. I infer that a

conversation which Mr. Damon, then a member of the advisory council, is

reported by Mr. Blount to have had with the ex-Queen on January 17th,

and which has been quoted in the newspapers, is the basis of this

astounding claim of the President of the United States of his authority

to adjudicate upon our right as a government to exist.

Mr. Damon, on the

occasion mentioned, was allowed to accompany the cabinet of the former

Government, who had been in conference with me and my associates, to

meet the ex-Queen. He went informally, without instructions and without

authority to represent the Government or to assure the ex-Queen "that if

she surrendered under protest her case would afterwards be fairly

considered by the President of the United States." Our ultimatum had

already been given to the members of the ex-cabinet who had been in

conference with us. What Mr. Damon said to the ex-Queen he said on his

individual responsibility and did not report it to us. Mr. Blount's

report of his remarks on that occasion furnish to the Government its

first information of the nature of those remarks. Admitting for

argument's sake that the Government had authorized such assurances, what

was "her case" that was afterwards to "be fairly considered by the

President of the United States?"

Was it the question of

her right to subvert the Hawaiian constitution and to proclaim a new one

to suit herself, or was it her claim to be restored to the sovereignty,

or was it her claim against the United States for the alleged

unwarrantable acts of Minister Stevens, or was it all these in the

alternative; who can say? But if it had been all of these, or any of

them, it could not have been more clearly and finally decided by the

President of the United States in favor of the Provisional Government

than when he recognized it without qualification and received its

accredited commissioners, negotiated a treaty of annexation with them,

received its accredited envoy extraordinary and minister

plenipotentiary, and accredited successively two envoys extraordinary

and ministers plenipotentiary to it ; the ex-Queen in the meantime being

represented in Washington by her agent who had full access to the

Department of State.

The whole business of

the Government with the President of the United States is set forth in

the correspondence between the two governments and the acts and

statements Of the minister of this Government at Washington and the

annexation commissioners accredited to it. If we have submitted our

right to exist to the United States, the fact will appear in that

correspondence and the acts of our commissioners.

Such agreement must be

shown as the foundation of the right of your Government to interfere,

for an arbitrator can be created only by the act of two parties.

The ex-Queen sent her

attorney.to Washington to plead her claim for reinstatement in power, or

failing that for a money allowance or damages. This attorney was refused

passage on the Government dispatch boat, which was sent to San Francisco

with the annexation commissioners and their message. The departure of

this vessel was less than two days after the new Government was

declared, and the refusal was made promptly upon receiving the request

therefore either on the day the Government was declared or on the next

day. If an intention to submit the question of the reinstatement of the

ex-Queen had existed, why should her attorney have been refused passage

on this boat? The ex-Queen's letter to President Harrison dated January

18, the day after the new Government was proclaimed, makes no allusion

to any understanding between her and the Government for arbitration.

Her letter is as follows

:

"His EXCELLENCY

BENJAMIN HARRISON, President of the United States:

MY GREAT AND GOOD

FRIEND :

It is with deep

regret that I address you on this occasion. Some of my subjects

aided by aliens, have renounced their loyalty and revolted against

the constitutional Government of my Kingdom.

They have attempted

to depose me and to establish a provisional government in direct

conflict with the organic law of this Kingdom. Upon receiving

incontestable proof that his excellency the minister plenipotentiary

of the United States, aided and abetted their unlawful movements and

caused United States troops to be landed for that purpose, I

submitted to force, believing that he would not have acted in that

manner unless by the authority of the Government which he

represents.

This action on my

part was prompted by three reasons: The futility of a conflict with

the United States; the desire to avoid violence, bloodshed and the

destruction of life and property, and the certainty which I feel

that you and your Government will right whatever wrongs may have

been inflicted upon us in the premises.

In due time a

statement of the true facts relating to this matter will be laid

before you, and I live in the hope that you will judge uprightly and

justly between myself and my enemies. This appeal is not made for

myself personally, but for my people, who have hitherto always

enjoyed the friendship and protection of the United States.

My opponents have

taken the only vessel which could be obtained here for the purpose,

and hearing of their intention to send a delegation of their number

to present their side of this conflict before you, I requested the

favor of sending by the same vessel an envoy to you, to lay before

you my statement, as the facts appear to myself and my loyal

subjects.

This request has

been refused, and I now ask you that in justice to myself and to my

people that no steps be taken by the Government of the United States

until my cause can be heard by you.

I shall be able to

dispatch an envoy about the 2nd of February, as that will be the

first available opportunity hence, and he will reach you by every

possible haste that there may be no delay in the settlement of this

matter. I pray you, therefore, my good friend, that you will not

allow any conclusions to be reached by you until my envoy arrives."

I beg to assure you

of the continuance of my highest consideration.

(Signed) LlLIUOKALANI R.

Honolulu, January

18, 1893

If any understanding had

existed at that time between her and the Government to submit the

question of her restoration to the United States, some reference to such

an understanding would naturally have appeared in this letter, as every

reason would have existed for calling the attention of the President to

that fact, especially as she then knew that her attorney would be

seriously delayed in reaching Washington. But there is not a word from

which such an understanding can be predicated. The Government sent its

commissioners to Washington for the sole object of procuring the

confirmation of the recognition by Minister Stevens of the new

Government and to enter into negotiations for political union with the

United States. The protest of the ex-Queen, made on January 17, is

equally with the letter devoid of evidence of any mutual understanding

for a submission of her claim to the throne to the United States. It is

evidently a protest against the alleged action of .Minister Stevens as

well as the new Government, and contains a. notice of her appeal to the

United States.

The document was

received exactly as it would have been received if it had come through

the mail. The endorsement of its receipt upon the paper was made at the

request of the individual who brought it as evidence of its safe

delivery.

As to the ex-Queen's

notice of her appeal to the United States, it was a matter of

indifference to us. Such an appeal could not have been prevented, as the

mail service was in operation as usual. That such a notice, and our

receipt of it without comment, should be made a foundation of a claim

that we had submitted our right to exist as a government to the United

States had never occurred to us until suggested to us by your

Government. The protest is as follows :

"I, Liliuokalani, by

the grace of God and under the constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom,

Queen, do hereby solemnly protest against any and all acts done

against myself and the constitutional Government of the Hawaiian

Kingdom by certain persons claiming to have established a

provisional government of and for this Kingdom.

"That I yield to the

superior force of the United States of America, whose minister

plenipotentiary, his excellency John L. Stevens, has caused United

States troops to be landed at Honolulu, and declared that be would

support the said provisional government.

"Now, to avoid any

collision of armed forces, and perhaps the loss of life, I do, under

this protest, and impelled by said force, yield my authority until

such time as the Government of the United States shall, upon the

facts being presented to it, undo the action of its representative

and reinstate me in the authority which I claim as the

constitutional sovereign of the Hawaiian Islands."

Done at Honolulu the

17th day of January, A. D. 1893

(Signed) LlLIUOKALANI, R.

SAMUEL PARKER,

Minister of Foreign Affairs.

WILLIAM H.

CORNWELL, Minister of Finance.

JOHN F. COLBURN,

Minister of the Interior.

A. P. PETERSON,

Attorney- General.

S. B. DOLE,

ESQ., and others, Composing the Provisional Government of the

Hawaiian Government

"Received by the

hands of the late cabinet this 17th day of January, A. D. 1893.

Sanford B. Dole, chairman of executive council of Provisional

Government."

You may not be aware,

but such is the fact, that at no time until the presentation of the

claim of the President of the United States of his right to interfere in

the internal affairs of this country, by you on December 19th, has this

Government been officially informed by the United States Government that

any such course was contemplated. And not until the publication of Mr.

Gresham's letter to the President of the United States on the Hawaiian

question had we any reliable intimation of such a policy. The adherents

of the ex-Queen have indeed claimed from time to time that such was the

case, but we have never been able to attach serious importance to their

rumors to that effect, feeling secure in our perfect diplomatic

relations with your country and relying upon the friendship and fairness

of a government whose dealings with us had ever shown a full recognition

of our independence as a sovereign power, without any tendency to take

advantage of the disparity of Strength between the two countries.

If your contention that

President Cleveland believes that this Government and the ex-Queen have

submitted their respective claims to the sovereignty of this country to

the adjudication of the United States is correct, then, may I ask, when

and where has the President held his court of arbitration? This

Government has had no notice of the sitting of such a tribunal and no

opportunity of presenting evidence of its claims. If Mr. Blount's

investigation were a part of the proceedings of such a court, this

Government did not know it and was never informed of it ; indeed, as I

have mentioned above, we never knew until the publication of Secretary

Gresham's letter to President Cleveland a few weeks ago, that the

American Executive had a policy of interference under contemplation.

Even if we had known that Mr. Blount was authoritatively acting as a

commissioner to take evidence upon the question of restoration of the

ex-Queen, the methods adopted by him in making his investigations, were,

I submit, unsuitable to such an examination or any examination upon

which human interests were to be adjudicated.

As I am reliably

informed, he selected his witnesses and examined them in secret, freely

using leading questions, giving no opportunity for a cross-examination,

and often not permitting such explanations by witnesses themselves as

they desired to make of evidence which he had drawn from them. It is

hardly necessary for me to suggest that under such a mode of examination

some witnesses would be almost helpless in the hands of an astute

lawyer, and might be drawn into saying things which would be only

half-truths, and standing alone would be misleading or even false in

effect.

Is it likely that an

investigation conducted in this manner could result in a fair, full, and

truthful statement of the case in point? Surely the destinies of a

friendly Government, admitting by way of argument that the right of

arbitration exists, may not be disposed of upon an ex parte and secret

investigation made without the knowledge of such Government or an

opportunity by it to be heard or even to know who the witnesses were.

Mr. Blount came here as

a stranger and at once entered upon his duties. He devoted himself to

the work of collecting information, both by the examination of witnesses

and the collection of statistics and other documentary matter, with

great energy and industry, giving up, substantially, his whole time to

its prosecution. He was here but a few months, and during that time was

so occupied with this work that he had little opportunity left for

receiving those impressions of the state of affairs which could best

have come to him, incidentally, through a wide social intercourse with

the people of the country and a personal acquaintance with its various

communities and educational and industrial enterprises. He saw the

country from his cottage in the center of Honolulu mainly through the

eyes of the witnesses whom he examined. Under these circumstances is it

probable that the most earnest of men would be able to form a statement

that could safely be replied upon as the basis of a decision upon the

question of the standing of a government ?

In view, therefore, of

all the facts in relation to the question of the President's authority

to interfere and concerning which the members of the executive were

actors and eyewitnesses, I am able to assure your excellency that by no

action of this Government, on the 17th day of January last, or since

that time, has the authority devolved upon the President of the United

States to interfere in the internal affairs of this country through any

conscious act or expression of this Government with such an intention.

You state in your

communication "After a patient examination of Mr. Blount's reports the

President is satisfied that the movement against the Queen if not

instigated was encouraged and supported by the representative of this

Government at Honolulu ; that he promised in advance to aid her enemies

in an effort to overthrow the Hawaiian Government and set up by force a

new government in its place ; that he kept his promise by causing a

detachment of troops to be landed from the Boston on the 16th of

January, 1893, and by recognizing the Provisional Government the next

day when it was too feeble to defend itself and the Constitutional

Government was able to successfully maintain its authority against any

threatening force other than that of e United States already landed."

Without entering into a

discussion of the facts I beg to state in reply that I am unable to

judge of the correctness of Mr. Blount's report from which the

President's conclusions were drawn, as I have had no opportunity of

examining such report. But I desire to specifically and emphatically

deny the correctness of each and every one of the allegations of fact

contained in the above-quoted statement; yet, as the President has

arrived at a positive opinion in his own mind in the matter, I will

refer to it from his standpoint.

My position, is briefly,

this: If the American forces illegally assisted the revolutionists in

the establishment of the Provisional Government that Government is not

responsible for their wrong-doing. It was purely a private matter for

discipline between the United States Government and its own officers.

There is, I submit, no precedent in international law for the theory

that such action of the American troops has conferred upon the United

States authority over the internal affairs of this Government. Should it

be true, as you have suggested, that the American Government made itself

responsible to the Queen, who, it is alleged lost her throne through

such action, that is not a matter for me to discuss, except to submit

that if such be the case, it is a matter for the American Government and

her to settle between them. This Government, a recognized sovereign

power, equal in authority with the United States Government and enjoying

diplomatic relations with it, can not be destroyed by it for the sake of

discharging its obligations to the ex-Queen.

Upon these grounds, Mr.

Minister, in behalf of my Government I respectfully protest against the

usurpation of its authority as suggested by the language of your

communication.

It is difficult for a

stranger like yourself, and much more for the President of the United

States, with his pressing responsibilities, his crowding cares and his

want of familiarity with the condition and history of this country and

the inner life of its people, to obtain a clear insight into the real

state of affairs and to understand the social currents, the race

feelings and the customs and traditions which all contribute to the

political outlook. We, who have grown up here or who have adopted this

country as our home, are conscious of the difficulty of maintaining a

stable government here. A community which is made up of five races, of

which the larger part but dimly appreciate the significance and value of

representative institutions, offers political problems which may well

tax the wisdom of the most experienced statesman.

For long years a large

and influential part of this community, including many foreigners and

native Hawaiians, have observed with deep regret the retrogressive

tendencies of the Hawaiian monarchy, and have honorably striven against

them, and have sought through legislative work, the newspapers, and by

personal appeal and individual influence to support and emphasize the

representative features of the monarchy and to create a public sentiment

favorable thereto, and thereby to avert the catastrophe that seemed

inevitable if such tendencies were not restrained. These efforts have

been met by the last two sovereigns in a spirit of aggressive hostility.