History of Later

Years

of the Hawaiian Monarchy

SUPPLEMENT A.

|

|

Report of Col. J. H. Blount

HONOLULU, H. L, July 17th, 1893

To The HON. WALTER Q. GRESHAM, Secretary of State, Washington, D. C.

Sir: On the 11th of March, 1893, I was appointed by the President of the United States as Special Commissioner to the Hawaiian Islands. At the same time the following instructions were given to me by you:

On the 29th of the same month I reached the City of Honolulu. The American Minister, the Hon. John L. Stevens, accompanied by a committee from the Annexation Club, came on board the vessel which had brought me. He informed me that this club had rented an elegant house, well furnished, and provided servants and a carriage and horses for my use; that I could pay for this accommodation just what I chose, from nothing up. He urged me very earnestly to accept the offer. I declined it, and informed him that I should go to a hotel.

The committee soon after this renewed the offer, which I again declined.

Soon afterward the ex-Queen, through her Chamberlain, tendered her carriage to convey me to my hotel. This I courteously declined.

I located myself at the Hawaiian Hotel. For several days I Was engaged receiving calls from persons of all classes and of various political views. I soon became conscious of the fact that all minds were quietly and anxiously looking to see what action the Government of the United States would take, The troops from the Boston were doing military duty for the Provisional Government. The American flag was floating over the Government building. Within it the Provisional Government conducted its business under an American protectorate, to be continued, according to the avowed purpose of the American- Minister, during negotiations with the United States for annexation.

My instructions directed me to make inquiries which, in the interest of candor and truth, could not be done when the minds of thousands of Hawaiian citizens were full of uncertainty as to what the presence of American troops, the American flag and the American protectorate implied. It seemed necessary that all these influences must be withdrawn before those inquiries could be prosecuted in a manner befitting the dignity and power of the United States.

Inspired with such feelings and confident no disorder would ensue, I directed the removal of the flag of the United States from the Government building and the return of the American troops to their vessels. This was accomplished without any demonstration of joy or grief on the part of the populace.

The afternoon before, in an interview with President Dole, in response to my inquiry, he said that the Provisional Government was now able to preserve order, although it could not have done so for several weeks after the proclamation establishing it.

In the evening of the same day the American Minister called on me with a Mr. Walter G. Smith, who, he said, desired to make an important communication to me and whom he knew to be very intelligent and reliable. Thereupon Mr. Smith, with intense gravity, informed me that he knew beyond doubt that it had been arranged between the Queen and the Japanese Commissioner that if the American flag and troops were removed the troops from the Japanese man-of-war Naniwa would land and reinstate the Queen.

Mr. Smith was the editor of the Hawaiian Star, established by the Annexation Club for the purpose of advocating annexation. The American Minister expressed his belief in the statement of Mr. Smith, and urged the importance of the American troops remaining on shore until I could communicate with you and you could have the opportunity to communicate with the Japanese Government and obtain from it assurances that Japanese troops would not be landed to enforce any policy on the Government or people of the Hawaiian Islands.

I was not impressed much with these statements. When the Japanese Commissioner learned that the presence of the Japanese man-of-war was giving currency to suggestions that his Government intended to interfere with domestic affairs here, he wrote to his Government asking that the vessel be ordered away, which was done. He expressed to me his deep regret that any one should charge that the empire of Japan, having so many reasons to value the friendship of the Government of the United States, would consent to offend that Government by interfering in the political conflicts in these islands, to which it was averse.

In the light of subsequent events I trust the correctness of my action will be the more fully justified. The Provisional Government left to its own preservation, the people freed from any fear of free intercourse with me in so far as my action could accomplish it, the disposition of the minds of all people to peace pending the consideration by the Government of the United States as to what should be its action in connection with affairs here, cleared the way for me to commence the investigation with which I was charged.

The causes of the revolution culminating in the dethronement of the Queen and the establishment of the Provisional Government, January 17th, 1893, are remote and proximate. A brief presentation of the former will aid in a fuller apprehension of the atter.

On the 18th of February, 1874, David Kalakaua was proclaimed King. In 1875 a treaty of commercial reciprocity between the United States and the Hawaiian Islands was ratified, and the laws necessary to carry it into operation were enacted in 1876. It provided, as you are aware, for the free importation into the United States of several articles among which was muscavado, brown, and all other unrefined sugars, syrups of sugar cane, melada, and molasses, produced in the Hawaiian Islands.

From it there came to the islands an intoxicating increase of wealth, a new labor system, an Asiatic population, an alienation between the native and white races, an impoverishment of the former, an enrichment of the latter, and the many so-called revolutions, which are the foundation for the opinion that stable government cannot be maintained.

In the year 1845, under the influence of white residents, the lands were so distributed between the Crown, the Government, the chief?, and the people as to leave the latter with an insignificant interest in lands, 27,830 acres.

The story of this division is discreditable to King, chiefs, and white residents, but would be tedious here. The chiefs became largely indebted to the whites, and thus the foundation for the large holdings of the latter was laid.

Prior to 1876 the Kings were controlled largely by such men as Dr. Judd, Mr. Wyllie, and other leading white citizens holding positions in their Cabinets.

A King rarely changed his Cabinet. The important offices were held by white men. A feeling of amity existed between the native and foreign races unmarred by hostile conflict. It should be noted that at this period the native generally knew how to read and write his native tongue, into which the Bible and a few English works were translated. To this, native newspapers of extensive circulation contributed to the awakening of his intellect. He also generally read and wrote English.

From 1820 to 1866 missionaries of various nationalities, especially American, with unselfishness, toil, patience, and piety, had devoted themselves to the improvement of the natives. They gave them a language, a religion, and an immense movement on the lines of civilization. In process of time the descendants of these good men grew up in secular pursuits. Superior by nature, education, and other opportunities, they acquired wealth. They sought to succeed to the political control exercised by their fathers. The reverend missionary disappeared. In his stead there came the Anglo-Saxon in the person of his son, ambitious to acquire wealth and to continue that political control reverently conceded to his pious ancestor. Hence, in satire, the native designated him a "missionary," which has become a campaign phrase of wonderful potency. Other white foreigners came into the country, especially Americans, English, and Germans. These, as a rule, did not become naturalized and participate in the voting franchise. Business and race affiliation occasioned sympathy and co-operation between these two classes of persons of foreign extraction.

Does this narration of facts portray a situation in a Government in whole or in part representative favorable to the ambition of a lender who will espouse the native cause? Would it be strange for him to stir the native heart by picturing a system of political control under which the foreigner had wickedly become possessed of the soil, degraded free labor by an uncivilized system of coolie labor, prostituted society by injecting into it a people hostile to Christianity and the civilization of the nineteenth century, exposed their own daughters to the evil influences, of an overwhelming male population of a degraded type, implanted Japanese and Chinese women almost insensible, to feelings of chastity, and then loudly boasted of their Christianity?

On the other hand, was it not natural for the white race to vaunt their wealth and intelligence, their Christian success in rescuing the native from barbarism, their gift of a Government regal in name but containing many of the principles of freedom; to find in the natives defective intelligence, tendencies to idolatry, to race prejudice, and a disposition under the influence of white and half-white leaders to exercise political domination; to speak of their thriftlessness in private life and susceptibility to bribes in legislative action; to proclaim the unchasteness of native women, and to take at all hazards the direction of public affairs from the native?

With such a powerful tendency to divergence and political strife, with its attendant bitterness and exaggerations, we must enter upon the field of inquiry pointed out in your instructions.

It is not my purpose to take up this racial controversy at its birth, but when it had reached striking proportions and powerfully acted in the evolution of grave political events culminating in the present status. Nor shall I relate all the minute details of political controversy at any given period, but only such and to such extent as may illustrate the purpose just indicated.

It has already appeared that under the Constitution of 1852 the Legislature consisted of two bodies one elected by the people and the other chosen by the King and that no property qualifications hindered the right of suffrage. The King and people through the two bodies held a check on each other.

It has also been shown that in 1864 by a royal proclamation a new Constitution, sanctioned by a Cabinet of prominent white men, was established, restricting the right of suffrage and combining the representative and nobles into one body. This latter provision was designed to strengthen the power of the Crown by removing a body distinctly representative. This instrument remained in force twenty-three years. The Crown appointed the nobles generally from white men of property and intelligence. In like manner the King selected his Cabinet. These remained in office for a long series of years and directed the general conduct of public affairs.

Chief Justice Judd of the Supreme Court of the Hawaiian Islands, in a formal statement, uses this language:

The record discloses thirteen Cabinets. Two of these were directly forced on him by the reformers. Of the others, six were in sympathy with the reformers and eminent in their confidence. The great stir in Cabinet changes commenced with the Gibson Cabinet in 1882. He was a man of large information, free from all suspicion of bribery, politically ambitious, and led the natives and some whites.

It may not be amiss to present some of the criticisms against Kalakaua and his party formally filed with me by Prof. W. D. Alexander, a representative reformer.

On the 12th of February, 1874, Kalakaua was elected King by the Legislature. The popular choice lay between him and the Queen Dowager.

In regard to this, Mr. Alexander says that "the Cabinet and the American Party used all their influence in favor of the former, while the English favored Queen Emma, who was devoted to their interest."

Notwithstanding there were objections to Kalakaua's character, he says: "It was believed, however, that if Queen Emma should be elected there would be no hope of our obtaining a reciprocity treaty with the United States."

He gives an account of various obnoxious measures advocated by the King which were defeated.

In 1882 he says the race issue was raised by Mr. Gibson, and only two white men were elected to the Legislature on the Islands.

A bill prohibiting the sale of intoxicating liquors to natives was repealed at this session.

A $10,000,000 loan bill was again introduced, but was shelved in committee. The appropriation bill was swelled to double the estimated receipts of the Government, including $30,000 for coronation expenses, besides large sums for military expenses, foreign embassies, etc.

A bill was reported giving the King power to appoint District Justices, which had formerly been done by the Justices of the Supreme Court.

A million of dollars of silver was coined by the King, worth 84 cents to the dollar, which was intended to be exchanged for gold bonds at par, under the loan act of 1882. This proceeding was enjoined by the court. The Privy Council declared the coin to be of the legal value expressed on their face, subject to the legal-tender act, and they were gradually put into circulation. A profit of $150,000 is said to have been made on this transaction.

In 1884 a reform Legislature was elected. A lottery bill, an opium-license bill and an $8,000,000 loan bill were defeated.

In the election for the Legislature of 1886 it is alleged that by the use of gin, chiefly furnished by the King, and by the use of his patronage, it was carried against the reform party; that out of twenty-eight candidates, twenty-six were office holders - one a tax assessor and one the Queen's secretary. There was only one white man on the Government ticket - Gibson's son-in-law. Only ten reform candidates were elected. In this Legislature an opium bill was passed providing for a license for four years, to be granted by the Minister of the Interior, with the consent of the King, for $30,000 per annum.

Another act was passed to create an Hawaiian Board of Health, consisting of five native doctors, appointed by the King, with power to issue certificates to native kahunas (doctors) to practice medicine.

A $2,000,000 loan bill was passed, which was used largely in taking up bonds on a former loan.

It is claimed that in granting the lottery franchise the King fraudulently obtained $75,000 for the franchise, and then sold it to another person, and that subsequently the King was compel led to refund the same.

These are the principal allegations on which the revolution of 1887 is justified.

None of the legislation complained of would have been considered a cause for revolution in any one of the United States, but would have been used in the elections to expel the authors from power. The alleged corrupt action of the King could have been avoided by more careful legislation and would have been a complete remedy for the future.

The rate of taxation on real or personal property never exceeded 1 per cent.

To all this the answer comes from the reformers: "The native is unfit for government, and his power must be curtailed."

The general belief that the King had accepted what is termed the opium bribe and the failure of his efforts to unite the Samoan Islands with his own kingdom had a depressing influence on his friends, and his opponents used it with all the effect they could.

The last Cabinet prior to the revolution of 1887 was antireform. Three of its members were half castes; two of them were and are recognized as lawyers of ability by all.

The amendments in the Constitution of 1887 disclose:

First: A purpose to take from the King the power to appoint nobles and to vest it in persons having $3,000 worth of unencumbered property or an annual income above the expense of living of $600. This gave to the whites three-fourths of the vote for nobles and one-fourth to the natives.

The provisos to the fourth section of Article 59 and Article 62 have this significant application. Between the years 1878 and 1886 the Hawaiian Government imported from Madeira and the Azores Islands 10,216 contract laborers, men, women, and children. Assume, for convenience of argument, that 2,000 of these were males of twenty years and upward. Very few of them could read and write. Only three of them were naturalized up to 1888, and since then only five more have become so. The remainder are subjects of Portugal. These were admitted to vote on taking the following oath and receiving the accompanying certificate:

I, the undersigned, Inspector of Elections, duly appointed and commissioned, do hereby certify that _____, aged , a native of , residing at _____, in said district, has this day taken before me the oath to support the Constitution of the Hawaiian Kingdom, promulgated and proclaimed on the 7th day of July, and the laws of said kingdom.

These ignorant laborers were taken before the election from the cane fields in large numbers by the overseers before the proper officer to administer the oath, and then carried to the polls and voted according to the will of the plantation manager. Why was this done? In the language of Chief Justice Judd, "to balance the native vote with the Portuguese vote." This same purpose is admitted by all persons here. Again, large numbers of Americans, Germans, English, and other foreigners un naturalized were permitted to vote under the foregoing form.

Two-thirds of this number were never naturalized, but voted under the above form of oath and certificate. They were citizens of the United States, Germany, and Great Britain, invited to vote under this Constitution to neutralize further the native voting strength. This same action was taken in connection with other European populations.

For the first time in the history of the country the number of nobles is made equal to the number of representatives. This furnished a veto power over the representatives of the popular vote to the nobles, who were selected by persons mostly holding allegiance, and not subjects of the kingdom. The election of a single representative by the foreign element gave to it the Legislature.

The power of appointing a cabinet was left with the King. His power to remove one was taken away. The removal could only be accomplished by a vote of want of confidence by a majority of all the elective members of the Legislature. The tenure of office of a cabinet minister henceforth depends on the pleasure of the Legislature, or, to speak practically, on the favor of certain foreigners, Americans and Europeans. Then it is declared that no act of the King shall have any effect, unless it be countersigned by a member of the cabinet, who by that signature makes himself responsible.

Power is taken from the King in the selection of nobles, not to be given to the masses, but to the wealthy classes, a large majority of whom are not subjects of the kingdom. Power to remove a cabinet is taken away from him, not to be conferred on a popular body, but on one designed to be ruled by foreign subjects. Power to do any act was taken from the King, unless by a member of the cabinet. This instrument was never submitted to the people for approval or rejection, nor was it ever contemplated by its friends and promoters, and of this no man will make issue.

Prior to this revolution, large quantities of arms bad been brought by a secret league from San Francisco, and placed among its members. The first election under this Constitution took place with the foreign population well armed and the troops hostile to the crown and people. The result was the election of what was termed a reform Legislature. The mind of an observer of these events notes henceforth a division of the people by the terms native and foreigner. It does not import race hostility simply. It is founded rather upon the attempted control of the country by a population of foreign origin and zealously holding allegiance to foreign powers. It had an alliance with natives of foreign parentage, some of whom were the descendants of missionary ancestors. Hence the terms "foreigner" and "missionary" in Hawaiian politics have their peculiar significance.

Foreign ships of great powers lying in the harbor of Honolulu to protect the persons and property of their citizens, and these same citizens left by their Government without reproof for participation in such events as I have related, must have restrained the native mind, from a resort to physical force. Its means of resistance was naturally what was left of political power.

In 1890 a Legislature was elected in favor of a new Constitution. The calculation of the reformers to elect all the nobles failed, owing to a defection of whites, especially among the intelligent laboring classes in the City of Honolulu, who were qualified to vote for nobles under the income clause. The cabinet installed by the revolution was voted out. A new Cabinet in harmony with the popular will, was appointed and remained in power until the death of the King in I891. In 1892 another Legislature was elected. Thrum's Handbook of Information for 1893, whose author, a reformer and annexationist, is intelligent, and in the employ of the Provisional Government, and whose work is highly valued by all persons, says, concerning the election:

The result brought to the Legislature three rather evenly balanced parties. This, with an admixture of self-interest in certain quarters, has been the means of much delay in the progress of the session, during which there have been no less than three new cabinets on "want-of-confidence" resolutions.

Judge Widemann of the National Reform Party divides the Legislature up thus: "Three parties and some independents the National Reform, Reform, and Liberal." There were nine members of the National Reform Party, fourteen members of the Reform, twenty-one Liberals, and four independents.

The Liberals favored the old mode of selecting nobles, the National Reform Party was in favor of a new Constitution reducing the qualification of voter for nobles, and the Reform Party was in opposition to both these ideas.

There were a number of members of all these faction-aspiring to be cabinet officers. This made certain individuals ignore party lines and form combinations to advance personal interests. The Reform Party seized upon the situation and made such combinations as voted out cabinet after cabinet until finally what was termed the Wilcox Cabinet was appointed. This was made up entirely of reformers. Those members of the National Reform and Liberal Parties who had been acting with the Reform Party to this point, and expecting representational the cabinet, being disappointed, set to work to vote out this cabinet, which was finally accomplished.

There was never a time when the Reform Party had any approach to a majority of members of the Legislature.

Let it be borne in mind that the time now was near at hand when the Legislature would probably be prorogued. Whatever cabinet was in power at the time of the prorogation had control of public affairs until a new Legislature should assemble two years afterward and longer, unless expelled by a vote of want of confidence.

An anti-reform cabinet was appointed by the Queen. Some faint struggle was made toward organizing to vote out this cabinet, but it was abandoned. The Legislature was prorogued. The reform members absented themselves from the session of that day in manifestation of their disappointment in the loss of power through the cabinet for the ensuing two years. The letters of the American Minister and naval officers stationed at Honolulu in 18J2 indicate that any failure to appoint a Ministry of the Reform Party would produce a political crisis. The voting out of the Wilcox Cabinet produced a discontent among the reformers verging very closely toward one, and had more to do with the revolution than the Queen's proclamation. The first was the foundation, the latter the opportunity.

In the Legislatures of 1890 and 1892, many petitions were filed asking for a new Constitution. Many were presented to the King and Queen. The discontent with the Constitution of 1887 and eagerness to escape from it controlled the elections against the party which had established it. Divisions on the mode of changing the Constitution, whether by legislative action or by Constitutional Convention, and the necessity for a two-thirds vote of the Legislature to effect amendments, prevented relief by either method. Such was the situation at the prorogation of the Legislature of 1892.

This was followed by the usual ceremonies at the palace on the day of prorogation - the presence of the Cabinet, Supreme Court Judges, Diplomatic Corps, and troops.

The Queen informed her cabinet of her purpose to proclaim a new Constitution, and requested them to sign it.

From the best information I can obtain the changes to the Constitution of 1887 were as follows:

Her Ministers declined to sign, and two of them communicated to leading reformers (Mr. L. A. Thurston, Mr. W. O. Smith, and others) the Queen's purpose and the position of the cabinet. Finding herself thwarted by the position of the cabinet, she declared to the crowd around the palace that she could not give them a new Constitution at that time on account of the action of her Ministers, and that she would do so at some future time. This was construed by some to mean that she would do so at an early day when some undefined, favorable opportunity should occur, and by others when a new Legislature should assemble and a new cabinet might favor her policy, or some other than an extreme and revolutionary course could be resorted to.

It seems that the members of the Queen's Cabinet, after much urging, prevailed upon her to abandon the idea of proclaiming a new Constitution. The co-operation of the cabinet appears to have been, in the mind' of the Queen, necessary to give effect to her proclamation. This method had been adopted by Kamehameha V, in proclaiming the Constitution of 1864. The Constitution of 1887 preserved this same form, in having the King proclaim that Constitution on the recommendation of the cabinet, which he had been prevailed upon by a committee from the mass meeting to appoint.

The leaders of the movement urged the members of the Queen's Cabinet not to resign, feeling assured that until they had done so the Queen would not feel that the power rested in her alone to proclaim a new Constitution. In order to give further evidence of her purpose to abandon the design of proclaiming it, a proclamation was published on the morning of the 16th of January, signed by herself and her Ministers, pledging her not to do so and was communicated to Minister Stevens that morning.

The following papers were among the files of the legation when turned over to me:

On the same day a mass meeting of between fifteen hundred and two thousand people assembled, attended by the leading men in the Liberal and National Reform parties, and adopted resolutions as follows:

Resolved, That the assurance of her Majesty the Queen contained in this day's proclamation is accepted by the people as a satisfactory guarantee that the Government does not and will not seek any modification of the Constitution by any other means than those provided in the organic law.

Resolved, That, accepting this assurance, the citizens here will give their cordial support to the Administration and indorse them in sustaining that policy.

To the communication inclosing the Queen's proclamation just cited, there appears to have been made no response. On the next day, as if to give further assurance, the following paper was sent to Mr. Stevens:

On the back of the first page of this communication, written in pencil, is the word "Declined." Immediately under the signature of the Attorney-General, also in pencil is written "1:30 to 1:45," and at the end on the second and last page this sentence, written in ink, appears:

"Received at the U. S. Legation about 2 P.M."

The cabinet itself could not be moved for two years, and the views of its members were well known to be against establishing a new Constitution by proclamation of the Queen and cabinet.

Nearly all of the arms on the Island of Oahu, in which Honolulu is situated, were in the possession of the Queen's Government. A military force, organized and drilled, occupied the station house, the barracks, and the palace the only points of strategic significance in the event of a conflict. The great body of the people moved in their usual course.

Women and children passed to and fro through the streets, seemingly unconscious of any impending danger, and yet there were secret conferences held by a small body of men, some of whom were Germans, some Americans, and some native-born subjects of foreign origin.

On Saturday evening, the 15th of January, they took up the subject of dethroning the Queen and proclaiming a new Government, with a view of annexation to the United States.

The first and most momentous question with them was to devise some plan to have the United States troops landed. Mr. Thurston, who appears to have been the leading spirit, on Monday sought two members of the Queen's Cabinet and urged them to head a movement against the Queen, and to ask Minister Stevens to land the troops, assuring them that in such an event Mr. Stevens would do so. Failing to enlist any of the Queen's Cabinet in the cause, it was necessary to devise some other mode to accomplish this purpose. A committee of safety, consisting of thirteen members, had been formed from a little body of men assembled in W. O. Smith's office. A deputation of these, informing Mr. Stevens of their plans, arranged with him to land the troops if they would ask it "for the purpose of protecting life and property." It was further agreed between him and them that in the event they should occupy the Government Building and proclaim a new Government he would recognize it. The two leading members of the committee, Messrs. Thurston and Smith, growing uneasy as to the safety of their persons, went to him to know if he would protect them in the event of their arrest by the authorities, to which he gave his assent.

At the mass meeting called by the Committee of Safety on the 16th of January, there was no communication to the crowd of any purpose to dethrone the Queen or to change the form of Government, but only to authorize the committee to take steps to prevent consummation of the Queen's purposes and to have guarantees of public safety. The Committee on Public Safety had kept their purposes from the public view at this mass meeting and at their small gatherings for fear of proceedings against them by the Government of the Queen.

After the mass meeting had closed, a call on the American Minister for troops was made in the following terms, and signed indiscriminately by Germans, by Americans, and by Hawaiian subjects of foreign extraction:

The response to that call does not appear in the files or on the records of the American Legation. It therefore cannot speak for itself. The request of the committee of safety was, however, consented to by the American Minister. The troops were landed.

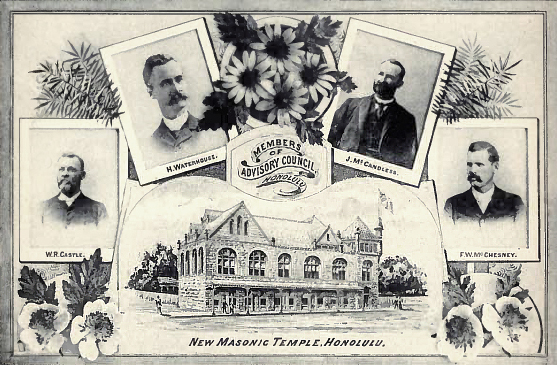

On that very night the committee assembled at the house of Henry Waterhouse, one of its members, living the next door to Mr. Stevens, and finally determined on the dethronement of the Queen, selected its officers, civil and military, and adjourned to meet the next morning.

Col. J. H. Soper, an American citizen, was selected to command the military forces. At this Waterhouse meeting it was assented to by all that Mr. Stevens had agreed with the committee of safety that in the event it occupied the Government building and proclaimed a Provisional Government he would recognize it as a de facto government.

When the troops were landed on Monday evening, January 16, about 5 o'clock, and began their march through the streets with their small arms, artillery, etc., a great surprise burst upon the community. To but few was it understood. Not much time elapsed before it was given out by members of the committee of safety that they were designed to support them.

At the palace, with the cabinet, amongst the leaders of the Queen's military forces, and the great body of the people who were loyal to the Queen, the apprehension came that it was a movement hostile to the existing Government. Protests were filed by the minister of foreign affairs and by the governor of the island against the landing of the troops.

Messrs. Parker and Peterson testify that on Tuesday at 1 o'clock they called on Mr. Stevens, and by him were informed that in the event the Queen's forces assailed the insurrectionary forces he would intervene.

At 2:30 o'clock of the same day the members of the Provisional Government proceeded to the Government building in squads and read their proclamation. They had separated in their march to the Government building for fear of observation and arrest. There was no sign of an insurrectionary soldier on the street The committee of safety sent to the Government building a Mr. A. S. Wilcox to see who was there, and on being informed that there were no Government forces on the grounds, proceeded in the manner 1 have related and read their proclamations.

Just before concluding the reading of their instrument fifteen volunteer troops appeared. Within a half hour afterward some thirty or forty made their appearance.

A part of the Queen's forces, numbering 224, were located at the station house, about one-third of a mile from the Government building. The Queen, with a body of 50 troops, was located at the palace, north of the Government building about 400 yards. A little northeast of the palace and some 200 yards from it, at the barracks, was another body of 272 troops. These forces had 14 pieces of artillery, 386 rifles, and 16 revolvers. West of the Government building and across a narrow street were posted Capt. Wiltse and his troops, these likewise having artillery and small-arms.

The Government building is in a quadrangular-shaped piece of ground surrounded by streets. The American troops were so posted as to be in front of any movement of troops which should approach the Government building on three sides, the fourth being occupied by themselves. Any attack on the Government from the east side would expose the American troops to the direct fire of the attacking force. Any movement of troops from the palace toward the Government building in the event of a conflict between the military forces would have exposed them to the fire of -the Queen's troops. In fact, it would have been impossible for a struggle between the Queen's forces and the forces of the committee of safety to have taken place without exposing them to the shots of the Queen's forces. To use the language of Admiral Skerrett, the American troops were well located if designed to promote the movement for the Provisional Government and very improperly located if only intended to protect American citizens in person and property.

They were doubtless so located to suggest to the Queen and her counsellors that they were in co-operation with the insurrectionary movement, and would when the emergency arose manifest it by active support.

It did doubtless suggest to the men who read the proclamation that they were having the support of the American minister and naval commander and were safe from personal harm. Why had the American minister located the troops in such a situation and then assured the members of the committee of safety that on their occupation of the Government building he would recognize it as a government de facto, and as such give it support? Why was the Government building designated to them as the place which, when there proclamation was announced therefrom, would be followed by his recognition. It was not a point of any strategic consequence. It did not involve the employment of a single soldier.

A building was chosen where there were no troops stationed, where there was no struggle to be made to obtain access, with an American force immediately contiguous, with the mass of the population impressed with its unfriendly attitude. Aye, more than this before any demand for surrender had even been made on the Queen or on the commander or any officer of any of her military forces at any of the points where her troops were located, the American minister had recognized the Provisional Government and was ready to give it the support of the United States troops!

Mr. Damon, the vice-president of the Provisional Government and a member of the advisory council, first went to the station house, which was in command of Marshal Wilson. The cabinet was there located. The vice-president importuned the cabinet and the military commander to yield up the military forces on the ground that the American minister had recognized the Provisional Government and that there ought to be no blood shed.

After considerable conference between Mr. Damon and the ministers he and they went to the Government building. The cabinet then and there was prevailed upon to go with the vice-president and some other friends to the Queen and urge her to acquiesce in the situation. It was pressed upon her by the ministers and other persons at that conference that it was useless for her to make any contest, because it was one with the United States; that she could file her protest against what had taken place and would be entitled to a hearing in the city of Washington. After consideration of more than an hour she finally concluded, under the advice of her cabinet and friends, to order the delivery up of her military forces to the Provisional Government under protest. That paper is in the following form:

All this was accomplished without the firing of a gun, without a demand for surrender on the part of the insurrectionary forces until they had been converted into a de facto government by the recognition of the American minister with American troops, then ready to interfere in the event of an attack.

In pursuance of a prearranged plan, the Government thus established hastened off commissioners to Washington to make a treaty for the purpose of annexing the Hawaiian Islands to the United States.

During the progress of the movement the committee of safety alarmed at the fact that the insurrectionists had no troops and no organization, dispatched to Mr. Stevens three persons, to wit: Messrs. L. A. Thurston, W. C. Wilder and H. F. Glade, "to inform him of the situation and ascertain from him what if any protection or assistance could be afforded by the United States for the protection of life and property, the unanimous sentiment and feeling being that life and property were in danger." Mr. Thurston is a native-born subject; Mr. Wilder is of American origin, but has absolved his allegiance to the United States and is a naturalized subject; Mr. Glade is a German subject.

The declaration as to the purposes of the Queen contained in the formal request for the appointment of a committee of safety in view of the facts which have been recited, to wit, the action of the Queen and her cabinet, the action of the Royalist mass meeting, and the peaceful movement of her followers, indicating assurances of their abandonment, seem strained in so far as any situation then requiring the landing of troops might exact.

The request was made, too, by men avowedly intending to overthrow the existing government and substitute a provisional government therefor, and who, with such purpose in progress of being effected, could not proceed therewith, but fearing arrest and imprisonment and without any thought of abandoning that purpose, sought the aid of the American troops in this situation to prevent any harm to their persons and property. To consent to an application for such a purpose without any e American minister, with naval forces under his command, could not otherwise be construed than as complicity with their plans.

The committee, to use their own language, say: " We are unable to protect ourselves without aid, and, therefore, pray for the protection of the United States forces."

In less than thirty hours the petitioners have overturned the throne, established a new government, and obtained the recognition of foreign powers.

Let us see whether any of these petitioners are American citizens, and if so whether they were entitled to protection, and if entitled to protection at this point whether or not subsequently thereto their conduct was such as could be sanctioned as proper on the part of American citizens in a foreign country.

Mr. Henry E. Cooper is an American citizen; was a member of the committee of safety; was a participant from the beginning in their schemes to overthrow the Queen, establish a Provisional Government, and visited Capt. Wiltse's vessel, with a view of securing the aid of American troops, and made an encouraging report thereon. He an American citizen, read the proclamation dethroning the Queen and establishing the Provisional Government.

Mr. F. W. McChesney is an American citizen; was co-operating in the revolutionary movement, and had been a member of the advisory council from its inception.

Mr. W. C. Wilder is a naturalized citizen of the Hawaiian Islands, owing no allegiance to any other country. He was one of the original members of the advisory council, and one of the orators in the mass meeting on the morning of January 16.

Mr. C. Bolte is of German origin, but a regularly naturalized citizen of the Hawaiian Islands.

Mr. A. Brown is a Scotchman and has never been naturalized.

Mr. W. O. Smith is a native of foreign origin and a subject of the Islands.

Mr. Henry Waterhouse, originally from Tasmania, is a naturalized citizen of the Islands.

Mr. Theo. F. Lansing is a citizen of the United States, owing and claiming allegiance thereto. He has never been naturalized in this country.

Mr. Ed. Suhr is a German subject.

Mr. L. A. Thurston is a native-born subject of the Hawaiian Islands, of foreign origin.

Mr. John Emmeluth is an American citizen.

Mr. W. R. Castle is a Hawaiian of foreign parentage.

Mr. J. A. McCandless is a citizen of the United States never having been naturalized here.

Six are Hawaiians subjects; five are American citizens; one English and one German. A majority are foreign subjects.

It will be observed that they sign as "Citizens' committee of safety."

This is the first time American troops were ever landed on these islands at the instance of a committee of safety without notice to the existing government.

It is to be observed that they claim to be a citizens' committee of safety and that they are not simply applicants for the protection of the property and lives of American citizens. The chief actors in this movement were Messrs. L. A. Thurston and W. O. Smith.

Alluding to the meeting of the committee of safety held at Mr. W. R. Castle's on Sunday afternoon, January 15, Mr. W. O. Smith says:

"After we adjourned Mr. Thurston and I called upon the American minister again and informed him of what was being done. Among other things we talked over with him what had better be done in case of our being arrested, or extreme or violent measures being taken by the monarchy in regard to us.

"We did not know what steps would be taken, and there was a feeling of great unrest and sense of danger in the community. Mr. Stevens gave assurance of his earnest purpose to afford all the protection that was in his power to protect life and property. He emphasized the fact that while he would call for the United States troops to protect life and property, he could not recognize any government until actually established."

Mr. Damon, the vice-president of the Provisional Government, origin, led and directed by two native subjects of the Hawaiian returning from the country on the evening of the 16th, and seeing the troops in the streets, inquired of Mr. Henry Waterhouse, "Henry, what does all this mean?

"To which he says, if he "remembers rightly," Mr. Waterhouse replied, "It is all up!" On being questioned by me as to his understanding of the expression, "It is all up," he said he understood from it that the American troops had taken possession of the island.

Mr. C. L. Carter, at the government house, assured Mr. Damon that the United States troops would protect them. Mr. Damon was astonished when they were not immediately marched over from Arion Hall to the government building and became uneasy. He only saw protection in the bodily presence of the American troops in this building. The committee of safety, with its frequent interviews with Mr. Stevens, saw it in the significance of the position occupied by the United States troops and in the assurance of Mr. Stevens that he would interfere for the purpose of protecting life and property, and that when they should have occupied the government building and read their proclamation dethroning the Queen and establishing the Provisional Government he would recognize it.

The committee of safety, recognizing the fact that the landing of the troops under existing circumstances could, according to all law and precedent, be done only on the request of the existing Government, having failed in utilizing the Queen's Cabinet, resorted to the new device of a committee of safety made up of Germans, British, Americans, and natives of foreign Islands.

With these leaders, subjects of the Hawaiian Islands, the American minister consulted freely as to the revolutionary movement and gave them assurance of protection from danger at the hands of the royal Government and forces.

On January 17, the following communication, prepared at the station house, which is one-third of a mile from the Government building and two-thirds of a mile from the residence of the American minister, was sent to him:

In it will be observed the declaration that the Provisional Government is claiming to have had his recognition. The reply of Mr. Stevens is not to he found in the records or files of the legation, but on those records appears the following entry:

This communication was received at the station house and read by all of the ministers and by a number of other persons. After this Mr. Samuel M; Damon, the vice-president of the Provisional Government, and Mr. Bolte, a member of the advisory council, came to the station house and gave information of the proclamation and asked for the delivery up of the station house, the former urging that the government had been recognized by the American minister, and that any struggle would cause useless bloodshed.

The marshal declared that he was able to cope with the forces of the Provisional Government and those of the United States successfully if the latter interfered, and that he would not surrender except by the written order of the Queen. After considerable conference, the cabinet went with Messrs. Damon and Bolte to the Government building and met the Provisional Government, and there indicated a disposition to yield, but said that they must first consult with the Queen.

The members of the Queen's cabinet, accompanied by Mr. Damon, preceded by the police, and met the Queen. There were also present Messrs. H. A. Widemann, Paul Neumann, E. C. Macfarlane, J. O. Carter, and others.

As to what occurred there I invite your attention to the following statement, made by the vice-president of the Provisional Government, and certified by him to be correct:

All the persons present except Mr. Damon formally state and certify that in this discussion it was conceded by all that Mr. Stevens had recognized the Provisional Government. This Mr. Damon says he does not clearly recollect, but that he is under the impression that at that time the Provisional Government had been ecognized. Save Mr. Damon, these witnesses testify to the impression made on their minds and on that of the Queen that the American minister and the American naval commander were co-operating in the insurrectionary movement. As a result of the conference, there was then and there prepared the protest which has been cited.

The time occupied in this conference is indicated in the following language by Mr. Damon:

We went over (to the Palace) between 4 and 5 and remained until 6 discussing the situation.

Mr. Damon and the cabinet returned to the Provisional Government, presented the protest, and President Dole indorsed on the same:

After this protest the Queen ordered the delivery of the station house, where was an important portion of the military forces, and the barracks, where was another force.

The statements of many witnesses at the station house and at the conference with the Queen, that the reply of Mr. Stevens to the cabinet on the subject of recognition had taken place, are not contradicted by Mr. Damon; but when inquired touching these matters, he uses such expressions as "I can not remember. It might have been so."

Mr. Damon says that he is under the impression that he knew when he went to this conference with the Queen that the recognition had taken place.

Mr. Bolte, another member of the Provisional Government, in a formal statement made and certified to by him, shows very much confusion of memory, but says: "I can not say what time in the day Mr. Stevens sent his recognition." He thinks it was after sunset.

Mr. Henry Waterhouse, another member of the Provisional Government, says: "We had taken possession of the barracks and station house before the recognition took place."

It will be observed that I have taken the communication of the Queen's ministers and the memorandum of Mr. Stevens as to his reply and the time thereof, to wit: "Not far from 5 p. m. I did not think to look at my watch."

This information was then transmitted to the station house, a distance of two-thirds of a mile, and before the arrival of Messrs. Damon and Bolte. This fact is supported by nine persons present at the interview with Mr. Damon and Mr. Bolte.

Then another period of time intervenes between the departure of Mr. Damon and Mr. Bolte. Then another period of time intervenes between the departure of Mr. Damon and the cabinet, passing over a distance of one-third of a mile to the Government Building. Then some further time is consumed in a conference with the Provisional Government before the departure of Mr. Damon . and the cabinet to the palace, were was the Queen. The testimony of all persons present proves that the recognition by Mr. Stevens had then taken place. Subsequent to the signing of the protest occurred the turning over of the military to the Provisional Government.

Inquiry as to the credibility of all these witnesses satisfies me as to their character for veracity, save one person, Mr. Colburn. He is a merchant, and it is said he makes misstatements in business transactions. No man can reasonably doubt the truth of the statements of the witnesses that Mr. Stevens had recognized the Provisional Government before Messrs. Damon and Bolte went to the station house.

Recurring to Mr. Stevens' statement as to the time of his reply to the letter of the cabinet, it does not appear how long before this reply he had recognized the Provisional Government.

Some witnesses fix it at three and some at half-past three. According to Mr. Damon he went over with the cabinet to meet the Queen between four and five, and taking into account the periods of time as indicated by the several events antecedent to this visit to the palace, it is quite probable that the recognition took place in the neighborhood of three o'clock. This would be within one-half hour from the time that Mr. Cooper commenced to read the proclamation establishing that Government, and allowing twenty minutes for its reading, in ten minutes thereafter the recognition must have taken place.

Assuming that the recognition took place at half-past three there was not at the Government building with the Provisional Government exceeding 60 raw soldiers.

In conversation with me Mr. Stevens said that he knew the barracks and station-house had not been delivered up when he recognized the Provisional Government; that he did not care anything about that, for 25 men, well armed, could have run the whole crowd.

There appears on the files of the legation this communication:

After the recognition by Mr. Stevens, Mr. Dole thus informs him of his having seen the Queen's Cabinet and demanded the surrender of the forces at the station-house. This paper contains the evidence that before Mr. Dole had ever had any conference with the Queen's ministers, or made any demand for the surrender of her military forces, the Provisional Government had been recognized by Mr. Stevens.

On this paper is written the following:

This is the only reference to it to be found on the records or among the files of the legation. This memorandum is not dated.

With the Provisional Government and its forces in a two-acre lot, and the Queen's forces undisturbed by their presence, this formal, dignified declaration on the part of the President of the Provisional Government to the American minister, after first thanking him for his recognition, informing him of his meeting with the Queen's cabinet and admitting that the stationhouse had not been surrendered, and stating that his forces may not be sufficient to maintain order, and asking that the American commander unite the forces of the United States with those of the Provisional Government to protect the city, is in ludicrous contrast with the declaration of the American minister in his previous letter of recognition that the Provisional Government was in full possession of the Government buildings, the archives, the treasury, and in control of the Hawaiian capital.

In Mr. Steven's dispatch to Mr. Foster, No. 79, January 18, 1893, is this paragraph:

Read in the light of what has immediately preceded, it is clear that he recognized the Provisional Government very soon after the proclamation of it was made. This proclamation announced the organization of the Government, its forms and officials. The quick recognition was the performance of his pledge to the committee of safety. The recognition by foreign powers, as herein stated, is incorrect. They are dated on the 18th, the day following that of Mr. Stevens.

On the day of the revolution neither the Portuguese charge d'affaires nor the French commissioner had any communication, written or oral, with the Provisional Government until after dark, when they went to the Government building to understand the situation of affairs. They did not then announce their recognition.

The British minister, several hours after Mr. Stevens' recognition, believing that the Provisional Government was sustained by the American minister and naval forces, and that the Queen's troops could not and ought not to enter into a struggle with the United States forces, and having so previously informed the Queen's cabinet, did go to the Provisional Government and indicate his purpose to recognize it.

I can not assure myself about the action of the Japanese commissioner. Mr. Stevens was at his home sick, and some one evidently misinformed him as to the three first.

In a letter of the Hawaiian commissioners to Mr. Foster, dated February 11, is this paragraph:

Mark the words, "and after the abdication by the Queen and the surrender to the Provisional Government of her forces." It is signed L. A. Thurston, W. C. Wilder, William R. Castle, J. Marsden, and Charles L. Carter.

Did the spirit of annexation mislead these gentlemen. If not, what malign influence tempted President Dole to a contrary statement in his cited letter to the American minister?

The Government building is a tasteful structure, with ample space for the wants of a city government of 20,000 people. It is near the center of a 2-acre lot. In it the legislature and supreme court hold their sessions and the cabinet ministers have their offices.

In one corner of this lot in the rear is an ordinary two story structure containing eight rooms. This building was and the Government survey office. In another corner is a small wooden structure containing two rooms used by the board of health.

These constitute what is termed in the correspondence between the Provisional Government and the American minister and the government of the United States "government departmental buildings."

Whatever lack of harmony of statement as to time may appear in the evidence, the statements in documents and the consecutive order of events in which the witnesses agree, all do force us to but one conclusion that the American minister recognized the Provisional Government on the simple fact that it had entered a house designated sometimes as the Government building and sometimes as Aliiolani Hale (sic), which had never been regarded as tenable in military operations and was not so regarded by the Queen's officers in the disposition of their military forces, these being at the station house, at the palace, and at the barracks.

Mr. Stevens consulted freely with the leaders of the revolutionary movement from the evening of the 14th. These disclosed to him all their plans. They feared arrest and punishment. He promised them protection. They needed the troops on shore to overawe the Queen's supporters and Government. This he agreed to and did furnish. The had few arms and no trained soldiers. They did not mean to fight. It was arranged between them and the American minister that the proclamation dethroning the Queen and organizing a provisional government should be read from the Government building and he would follow it with a speedy recognition. All this was to be done with American troops provided with small-arms and artillery across a narrow street within a stone's throw. This was done.

Then commenced arguments and importunities to the military commander and the Queen that the United States had recognized the Provisional Government and would support it; that for them to persist involved useless bloodshed.

No soldier of the Provisional Government ever left the two acre lot.

The Queen finally surrendered, not to these soldiers and their leaders but to the Provisional Government on the conviction that the American minister and the American troops were promoters and supporters of the revolution, and that she could only appeal to the Government of the United States to render justice to her.

The leaders of the revolutionary movement would not have undertaken it but for Mr. Stevens' promise to protect them against any danger from the Government. But for this their mass meeting would not have been held. But for this no request to land the troops would have been made. Had the troops not been landed no measures for the organization of a new Government would have been taken.

The American minister and the revolutionary leaders had determined on annexation to the United States, and had agreed on the part each was to act to the very end.

Prior to 1887 two-thirds of the foreigners did not become naturalized. The Americans, British and Germans especially would not give up the protection of those strong governments and rely upon that of the Hawaiian Islands. To such persons the constitution of 1887 declared: "We need your vote to overcome that of our own native subjects. Take the oath to support the Hawaiian Government, with a distinct reservation of allegiance to your own." Two-thirds of the Europeans and Americans now voting were thus induced to vote in a strange country with the pledge that such act did not affect their citizenship to their native country. The purport and form of this affidavit appear in the citations from the constitution of 1887 and the form of oath of a foreign voter.

The list of registered voters of American and European origin, including Portuguese, discloses 3,715; 2,091 of this number are Portuguese. Only eight of these imported Portuguese have ever been naturalized in these islands. To this should be added 106 persons, mostly negroes, from the Cape Verde Islands, who came here voluntarily several years prior to the period of state importation of laborers.

The commander of the military forces of the Provisional Government on the day of the dethroning of the Queen and up to this hour has never given up his American citizenship, but expressly reserved the same in the form of oath already disclosed and by a continuous assertion of the same.

The advisory council of the Provisional Government, as established by the proclamation, consisted of John Emmeluth, an American, not naturalized; Andrew Brown, a Scotchman, not naturalized; C. Bolte, naturalized; James F. Morgan, naturalized; Henry Waterhouse, naturalized; S. M. Damon, native; W. G. Ashley, an American, not naturalized; E. D. Tenney, an American, not naturalized; F. M. McChesney, an American, not naturalized; W. C. Wilder, naturalized; J. A. McCandless, an American, not naturalized; W. R. Castle, a native; Lorrin A. Thurston, a native; F. J. Wilhelm, an American, not naturalized.

One-half of this body, then, was made up of persons owing allegiance to the United States and Great Britain.

The annexation mass meeting of the 16th of January was made up in this same manner.

On the 25th of February, 1843, under pressure of British naval forces, the King ceded the country to Lord George Paulet, "subject to the decision of the British Government after full information." That Government restored their independence. It made a deep impression on the native mind.

This national experience was recalled by Judge Widemann, a German of character and wealth, to the Queen to satisfy her that the establishment of the Provisional Government, through the action of Capt. Wiltse and Mr. Stevens, would be repudiated by the United States Government, and that she could appeal to it. Mr. Damon urged upon her that she would be entitled to such a hearing. He was the representative of the Provisional Government, and accepted her protest and turned it over to President Dole. This was followed by large expenditures from her private purse to present her cause and to invoke her restoration.

That a deep wrong has been done the Queen and the native race by American officials pervades the native mind and that of the Queen, as well as a hope for redress from the United States, there can be no doubt.

In this connection it is important to note the inability of the Hawaiian people to cope with any great powers, and their recognition of it by never offering resistance to their encroachments.

The suddenness of the landing of the United States troops, the reading of the proclamation of the Provisional Government almost in their presence, and the quick recognition by Mr. Stevens, easily prepared her to the suggestion that the President of the United States had no knowledge of these occurrences and must know of and approve or disapprove of what had occurred at a future time. This, too, must have contributed to her disposition to, accept the suggestions of Judge Widemann and Mr. Damon. Indeed, who could have supposed that the circumstances surrounding her could have been foreseen and sanctioned deliberately by the President of the United States.

Her uniform conduct and the prevailing sentiment amongst the natives point to her belief as well as theirs that the spirit of justice on the part of the President would restore her crown. The United States troops, it appears, were doing military duty for the Provisional Government before the protectorate was assumed, just as afterwards. The condition of the community at the time of the assumption of the protectorate was one of quiet and acquiescence, pending negotiations with the United States, so far as I have been able to learn.

A few days before my arrival here news of the withdrawal by the President from the Senate of the treaty of annexation and his purpose to send a commissioner to inquire into the revolution was received.

An organization known as the Annexation Club commenced to obtain signatures to a petition in favor of annexation. This work has been continued ever since.

The result is reported on July 9th, 1893, thus:

The Portuguese have generally signed the annexation rolls. These, as I have already stated, are nearly all Portuguese subjects. A majority of the whites of American and European birth who have signed the same roll are not Hawaiian subjects and are not entitled to vote under any laws of the Kingdom.

The testimony of leading annexationists is that if the question of annexation were submitted to a popular vote, excluding all persons who could not read or write except foreigners (under the Australian ballot system, which is the law of the land) that annexation would be defeated.

From a careful inquiry I am satisfied that it would be defeated by a vote of at least two to one. If the votes of persons claiming allegiance to foreign countries were excluded, it would be defeated by more than five to one.

The undoubted sentiment of the people is for the Queen, against the Provisional Government and against annexation. A majority of the whites, especially Americans, are for annexation.

The native registered vote in 1890 was 9,700; the foreign vote was 3,893. This native vote is generally aligned against the annexation whites. No relief is hoped for from admitting to the right of suffrage the overwhelming Asiatic population. In this situation the annexation whites declare that good government is unattainable.

The controlling element in the white population is connected with the sugar industry. In its interest the Government here has negotiated treaties from time to time for the purpose of securing contract laborers for terms of years for the plantations, and paid out large sums for their transportation and for building plantation wharves, etc.

These contracts provide for compelling the laborer to work faithfully by fines and damage suits brought by the planters against them, with the right on the part of the planter to deduct the damages and cost of the suit out of the laborer's wages. They also provide for compelling the laborer to remain with the planter during the contract term. They are sanctioned by law and enforced by civil remedies and penal laws. The general belief amongst the planters at the so-called revolution was that, notwithstanding the laws against importing labor into the United States in the event of their annexation to that Government, these laws would not be made operative in the Hawaiian Islands on account of their peculiar conditions. Their faith in the building of a cable between Honolulu and San Francisco, and large expenditures at Pearl Harbor in the event of annexation have also as much to do with the desire for it.

In addition to these was the hope of escape from duties on rice and fruits and receiving he sugar bounty, either by general or special law.

The repeal of the duty on sugar in the McKinley act was regarded a severe blow to their interests, and the great idea of statesmanship has been to do something in the shape of treaties with the United States, reducing their duties on agricultural products of the Hawaiian Islands, out of which profits might be derived. Annexation has for its charm the complete abolition of all duties on their exports to the United States.

The annexationists expect the United States to govern the islands by so abridging the right of suffrage as to place them in control of the whites.

The Americans, of what is sometimes termed the better class, in point of intelligence, refinement, and good morals, are fully up to the best standard in American social life. heir homes are tasteful and distinguished for a generous hospitality. Education and religion receive at their hands zealous support. The remainder of them contain good people of the laboring class and the vicious characters of a seaport city. These general observations can be applied to the English and German population.

The native population, numbering in 1890, 40,622 persons, contained 27,901 able to read and write. No country in Europe, except perhaps Germany and England, can make such a showing. While the native generally reads and writes in native and English, he usually peaks the Kanaka language. Foreigners usually acquire it. The Chinese and Japanese learn to use it and know very little English.

Among the natives there is not a superior class, indicated by great wealth, enterprise, and culture, directing the race, as with the whites. This comes from several causes.

In the distribution of lands most of it was assigned to the King, chiefs, some whites, and to he Government for its support. Of the masses 11,132 persons received 27,830 acres about two and a half acres to an individual called Kuleanas. The majority received nothing. The foreigners soon traded the chiefs out of a large portion of their shares, and later purchased from the Government, government lands and obtained long leases on the crown lands. Avoiding details it must be said that the native never held much of the land. It is well known that it has been about seventy years since he commenced to emerge from idolatry and the simplicity of thought and habits and immoralities belonging to it. National tradition has done little for him, and before the whites led him to education its influence was not operative. Until within the last twenty years white leaders were generally accepted and preferred by the King in his election of cabinets, nobles, and judges, and native leadership was not wanted.

Their religious affiliations are with the Protestant and Catholic churches. They are overgenerous, hospitable, almost free from revenge, very courteous especially to females. heir talent for oratory and the higher branches of mathematics is unusually marked. In person they have large physique, good features and the complexion of the brown races. hey have been greatly advanced by civilization, but have done little towards its advancement. The small amount of thieving and absence of beggary are more marked than amongst the best races of the world. What they are capable of under fair conditions s an unsolved problem.

Idols and idol worship have long since disappeared.

The following observations in relation to population are presented, though some repetition will be observed:

The population of the Hawaiian Islands can best be studied, by one unfamiliar with the native tongue, from its several census reports. A census is taken every six years. The last report is for the year 1890. From this it appears that the whole population numbers 9,990. This number includes natives or, to use another designation, Kanakas, half-castes persons containing an admixture of other than native blood in any proportion with it), Hawaiian-born foreigners of all races or nationalities other than natives, Americans, ritish, Germans, French, Portuguese, Norwegians, Chinese, Polynesians, and other nationalities.

(In all the official documents of the Hawaiian Islands, whether in relation to population, ownership of property, taxation, or any other question, the designation "American," Briton," "German," or other foreign nationality does not discriminate between the naturalized citizens of the Hawaiian Islands and those owing allegiance to foreign countries.)

Americans number 1,928; natives and half-castes, 40,612; Chinese, 15,301; Japanese, 2,360; Portuguese, 8,602; British, 1,344; Germans, 1,034; French, 70; Norwegians, 27; Polynesians, 588, and other foreigners. 419.

It is well at this point to say that of the 7,495 Hawaiian-born foreigners 4,117 are Portuguese, 1,701 Chinese and Japanese, 1,617 other white foreigners, and 60 of other nationalities.

There are 58,714 males. Of these 18,364 are pure natives and 3,085 are half-castes, making together 21,449. Fourteen thousand five hundred and twenty-two 14,522) are Chinese. The Japanese number 10,079. The Portuguese contribute 4,770. These four nationalities furnish 50,820 of the male population.

The Americans 1,298 The British 982 The Germans 729 The French 46 The Norwegians 135

These five nationalities combined furnish 3,170 of the total male population.

The first four nationalities when compared with the last five in male population are nearly sixteenfold the largest in number.

The Americans are to those of the four aforementioned group of nationalities as 1 to 39 - nearly as 1 to 40.

Portuguese have been brought here from time to time from the Madeira and Azores Islands by the Hawaiian Government as laborers, on plantations, just as has been done in elation to Chinese, Japanese, Polynesians, etc. They are the most ignorant of all imported laborers, and reported to be very thievish. They are not pure Europeans, but a commingling of many races, especially the negro. Very few of them can read and write. Their children are being taught in the public schools, as all races are. It is wrong to class them as Europeans.

The character of the people of these islands is and must be overwhelmingly Asiatic. Let it not be imagined that the Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese disappear at the end of their contract term.

In 1890 the census report discloses that the only 4,695 persons owned real estate in these islands. With a population estimated at this time at 95,000, the vast number of landless people here is discouraging to the idea of immigrants from the United States being able to find encouragement in the matter of obtaining homes in these islands.

The landless condition of the native population grows out of the original distribution and not from shiftlessness. To them homesteads should be offered rather than to strangers.

The census reports of the Hawaiian Islands pretend to give the native population from the period when Capt. Cook was here until 1890. These show a rapid diminution in numbers, which, it is claimed, indicate the final extinction of the race. Very many of these reports are entirely conjectural and others are carelessly prepared. That of 1884 is believed by many intelligent persons here to overstate the native strength and, of course, to discredit any comparison with that of 1890.

All deductions from such comparisons -arc discredited by an omission to consider loss from emigration. Jarves, in his history of the Hawaiian Islands,- published in 1847, says:

"Great numbers of healthy Hawaiian youths have left in whale ships and other vessels and never returned. The number annually afloat is computed at 3,000. At one time 400 were counted at Tahiti, 500 in Oregon, 50 at Paita, Peru, besides unknown numbers in Europe and the United States."

In 1850 a law was passed to prohibit natives from leaving the islands. The reason for it is stated in the following preamble.

"Whereas, by the census of the islands taken in 1849, the population decreased at the rate of 8 per cent in 1848, and by the census taken in 1850 the population decreased at the rate of 5^ per cent in 1849; whereas the want of labor is severely felt by planters and other agriculturists, whereby the price of provisions and other produce has been unprecedentedly enhanced, to the great prejudice of the islands; whereas, many natives have emigrated to California and there died in great misery; and, whereas, it is desirable to prevent such loss to the nation and such wretchedness to individuals, etc."

This act remained in force until 1887. How effective it was when it existed there is no means of ascertaining. How much emigration of the native race has taken place since its repeal does not appear to have been inquired into by the Hawaiian Government. Assuming that there has been none and that the census tables are correct, except that of 1884, the best opinion is that the decrease in the native population is slight now and constantly less. Its final extinction, except by amalgamation with Americans, Europeans, and Asiatics, may be dispensed with in all future calculations.

My opinion, derived from official data and the judgment of intelligent persons, is that it is not decreasing now and will soon increase.

The foregoing pages are respectfully submitted as the connected report indicated in your instructions. It is based upon the statements of individuals and the examination of public documents. Most of these are hereto annexed.

The partisan feeling naturally attaching to witnesses made it necessary for me to take time for forming a correct judgment as to their character. All this had to be done without the counsel of any other person.

Mindful of my liability to error in some matters of detail, but believing in the general correctness of the information reported and conclusions reached, I can only await the judgment of others.

I am, sir, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

Report of the Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs in Relation to the Hawaiian Islands

Mr. Morgan submitted the following report from the Committee on Foreign Relations:

The following resolution of the Senate defines the limits of the authority of the committee in the investigation and report it is required to make:

The witnesses were examined under oath when it was possible to secure their appearance before the committee, though in some instances affidavits were taken in Hawaii and other places, and papers of a scientific and historic character will be appended to this report and presented to the Senate for its consideration.

The committee did not call the Secretary of State, or any person connected with the Hawaiian Legation, to give testimony. It was not thought to be proper to question the diplomatic authorities of either government on matters that are, or have been, the subject of negotiation between them, and no power exists to authorize the examination of the minister of a foreign government in an}' proceeding without his consent.

The resolutions include an inquiry only into the intercourse between the two governments, and regard the conduct of the officers of the United States as a matter for domestic consideration in which Hawaii is not concerned, unless it be that their conduct had some unjust and improper influence upon the action of the people or Government of that country in relation to the revolution.