Natural History of

Hawai`i

SECTION TWO – GEOLOGY, GEOGRAPHY

AND TOPOGRAPHY OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS

|

CHAPTER 8: Coming of Pele and an Account of the Low Islands of the Group

Pele's Journey to Hawaii

There is perhaps no better way to begin an account of the natural history of the Hawaiian Islands than by recounting an Hawaiian legend that tells of the coming of Pele, that powerful mythical deity of fire and flood, feared and respected by all the ancient inhabitants of the group as the source, as well as the end, of all the wonderful volcanic phenomena with which they were familiar.

In the beginning, so one version of the legend runs, long, long ago, before things were as they now are, there was born a most wonderful child called Pele. Hapakuela was the land of her birth, a far distant land out on the edge of the sky—away, ever so far away to the southwest. There she lived with her parents and her brothers and sisters, as a happy child until she had grown to womanhood, when she fell in love and was married. But ere long her husband grew neglectful of her and her charms, and at length was enticed away from her and from their island home. After a dreary period of longing and waiting for her lover, Pele determined to set out on the perilous and uncertain journey in quest of him.

When the time came for the journey her parents, who must have been very remarkable people indeed, made her a gift of the sea to bear her canoes upon. We are told that among other wonderful gifts Pele had power to pour forth the sea from her forehead as she went. So, when all was in readiness, she and her brothers set forth together, singing, making songs, and sailing—on, on, on over the new-made sea—out over the great unknown in the direction of what we now know as the Hawaiian Islands.

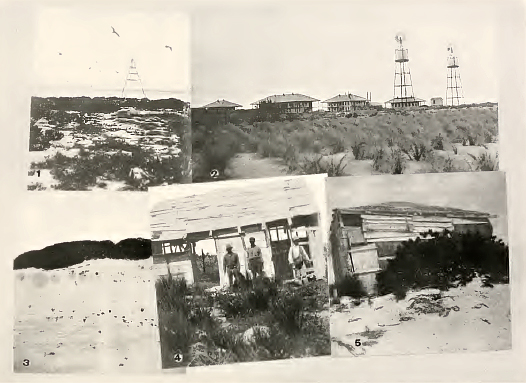

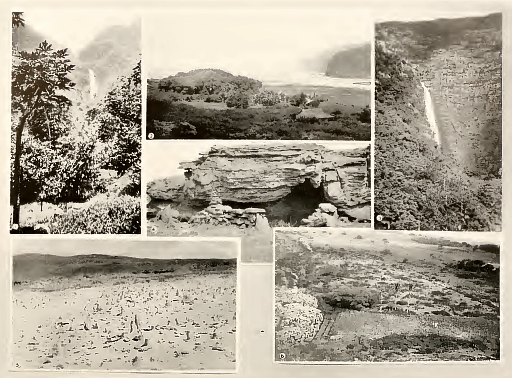

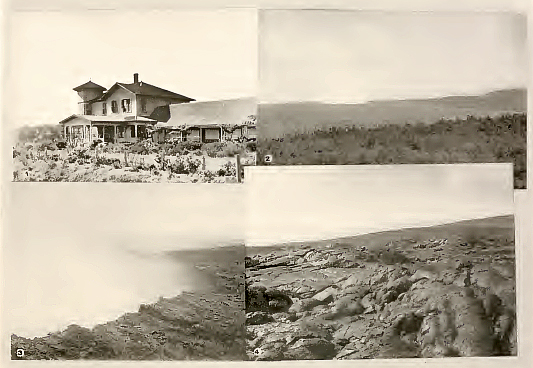

PLATE 19: VIEWS ON MIDWAY AND OCEAN ISLANDS

1. Midway Island; looking from sand islet towards green islet, showing the characteristic vegetation. 2. Showing the cable station on Midway Island. Note the growth of sand grass (Cynodon dactylon) in the foreground. 3. View on Ocean Island showing the formation of sand hills under the protection of the low bushes. 4. Hut built on green islet by Japanese bird poachers. 5. Midway Island home of Capt. Walker and family, who were shipwrecked on the island in 1887 and spent fourteen months there before being rescued. (The hut has since been burned).

But in the time of which the legend tells the islands of Hawaii were not islands at all, but were a group of vast unwatered Mountains standing on a great plain that has since become the ocean floor. There was not even fresh water on these mountains until Pele brought it. But as she journeyed in search of her husband, the waters of the sea preceded her, covering over the bed of the ocean. It rose before her until only the tops of the highest mountains were visible; all else was covered by the mighty deluge. As time went on, the water receded to the present level, and thus it was that the sea was brought to Hawaii-nei.

From her coming until now, Pele has continued to dwell in the Hawaiian Islands. According to the legend, her home was first on Kauai—one of the northern islands of the group. From there she moved to Molokai and settled in the crater Kauhako. Later she removed to Maui and established herself in the crater hill of Puulaina, near Lahaina. After a time she moved again to Haleakala, where she hollowed out that mighty crater. Finally, as a last resort, she settled in the great crater of Kilauea, on Hawaii, where she has even since made her abode.

In this way Pele came to be the presiding goddess of Kilauea and to rule over its fiery flood, and from those ancient days to the present, she has been respected as the ranking goddess of all volcanoes, with power at her command to lift islands from the sea, to rend towering mountain peaks, to make the very earth tremble at her command, to obscure the sun with stifling smoke, to cause rivers of molten rock to flow down the mountains like water, and above all to keep the fires forever burning in her subterranean abode.

This interesting legend should be regarded as a sincere effort of the Hawaiian mind to account for the presence in the islands of the primeval power they saw in the volcano and to explain certain fundamental phenomena of nature which surrounded them on every hand. Here were the islands, here were the burning mountains, here was the great sea, here were the people, the animals and the plants. Whence came they all, and how did they come to be?

Legend and Science Agree

With all our boasted science, we are still groping, as were the ancient Hawaiians, seeking an explanation of the beginning of the islands, and of the marvelous variety of life which they support. In the search, science has substituted theory for legend, and observation for myth, but when we compare the legendary course of Pele as she moved her home, from the oldest island, Kauai, to the young island, Hawaii, with the theory that geologists have worked out to account for certain basic facts in the evolution of the group, we are surprised to find that legend so closely accords with the modern accepted theory of tile succession in time of the extinction of the volcanic fires that marked the completion of one island after another, until Hawaii alone can boast of the possession of the eternal fires.

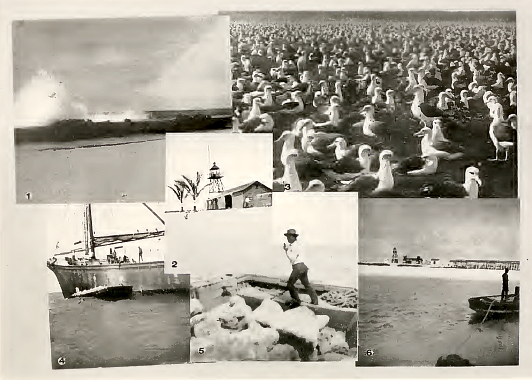

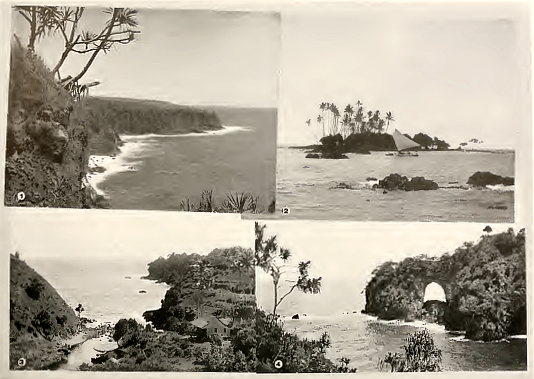

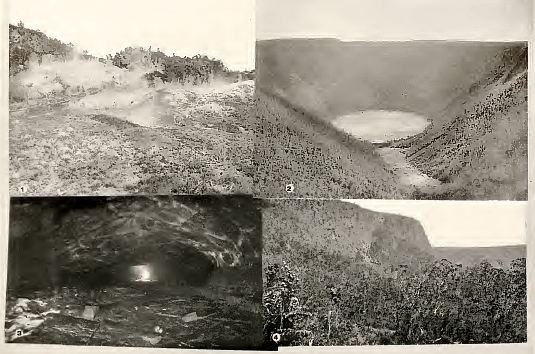

PLATE 20: VIEWS OF LAYSAN ISLAND

1. Shows the sea breaking along the rocky ledge at the southeast point. 2. The lighthouse and manager’s quarters showing two cocoanut trees brought from Strong’s Island. 3. Laysan Albatross. 4. Loading guano in a large schooner. 5. A lighter load of guano. 6. General view of the settlement on the “harbor” (west) side of the island.

Geographic Position of the Islands

Considering the Hawaiian Islands in relation to each other and to the rest of the world, we find this wonderful group of mid-Pacific islands to he made up of twenty-one islands and a number of other small islets that are contiguous to the shores of the larger ones. For the sake of convenience, the group, which stretches for about 2,000 miles from southeast to northwest, has been divided into the leeward or northwest, and the windward or inhabited chain. In the leeward islands are grouped eight low coral islands and reefs, and five of the lowest of the high islands. Beginning at the western extremity, the low group includes Ocean Island, ten feet high; Midway Island, fifty-seven feet high; Gambier Shoal, Pearl and Hermes Reef, Lisiansky Island, fifty feet high; Laysan Island, forty feet high, and Maro and Dowsett Reefs.

These are probably the tops of submerged mountains that have had their summits brought up to or above the surface of the ocean by the combined action of the hardy reef-building corals, the waves, and the transporting power of the wind. The wind has had an important part in their final form, since it has gathered up the dry soil left above the ordinary action of the wave and piled it, as at Midway, in the center of a secure enclosure, formed by an encircling coral reef, or as at Laysan, to form a sand rim about an elevated coral lagoon.

Lying between the group of low islands and forming a connecting link with the high or inhabited group, are five islands, the lowest of the high islands. They form a transition group between the coral and the volcanic islands and a second division of the leeward chain, and are made up of Gardner Island. 170 feet high; French Frigates Shoal, 120 feet high; Necker Island, 800 feet high; Frost Shoal, and Nihoa or Bird Island, 903 feet high.

Together with the low islands, they form the leeward chain of thirteen islets, reefs and shoals that have a combined area of something over six square miles, or about four thousand acres. With the exception of Midway, which is the relay station for the Commercial Pacific Cable Company's wire across the Pacific, they are uninhabited at the present time. The entire chain, with the exception of Midway, has been set aside by the federal government to form the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation, which, taken collectively, forms the largest and most populous bird colony in the world.

To many these remote, shimmering, uninhabited islands are devoid of interest; to the naturalist, however, every square foot of the surface, and all the life that inhabits them, has an interesting story to tell. The geologist finds in them subjects of the greatest interest and importance. The thrilling story of their up-building through centuries by the tireless activity of the tiny animal, the coral polyp, that by nature is endowed with the mysterious power of extracting certain elements in solution from the sea water and little by little transforming them into a reef of solid lime-stone masonry, which, in time, becomes the foundation of inhabited land is indeed most wonderful.

As the formation and growth of coral islands and reefs has been a subject profound enough to engage the attention of such thinkers as Darwin, Agassiz, Dana, Wallace, and a score of others, it is small wonder that these coral islands, which gem the surface of our summer seas, are invested with vital interest for those who feel a scientific concern in them and who are permitted to study them.

Ocean Island

The leeward chain furnishes interesting examples of the various types of coral islands. Ocean Island, the extreme western end of the Hawaiian chain, lies in 178° 29' 45" west longitude, and 28° 25' 45" north latitude, and is almost at the antipodes from Greenwich, and, as it lies in the northern limit of the coral belt, it furnishes an excellent example of a circular barrier atoll in mid-ocean. The coral rim surrounds and forms a barrier about four small sand islets and is approximately sixteen miles in circumference. The rim is broken for a mile or more on the western side, but the lagoon enclosed is too shallow to admit the entrance of sea-going ships. Over this low coral rim the curving line of white breakers beat, forming a snowy girdle about the low islets that lie protected within.

Midway Island

Midway Island is fifty-six miles to the east of Ocean Island, and, like it, is made up of a low circular coral rim or atoll, six miles in diameter, averaging five feet in height by twenty feet in width, which is open to the west. Like Ocean, it has one fair-sized sand islet and one that is covered with shrubbery. These islets lie in the southern part of the circle, about a mile apart, and are utilized as stations by the cable company. The coral rim encloses an area of about forty square miles of quiet water which attains a depth of eight fathoms. The island was discovered in 1859 by Captain Brooks, who took possession of it for the United States. Attempts to utilize it as a coaling station were abandoned after a single trial; but in 1902 it was successfully occupied by the cable company, and has since been regularly visited by vessels carrying provisions and supplies.

Just prior to my visit in 1902, which preceded the arrival of the cable by a few months, the island had been visited and devastated by a party of poachers engaged in securing birds' feathers for millinery purposes. The dead bodies of thousands of birds, ruthlessly slaughtered by them for their wings and tails, were thickly strewn over both islets. The reports made at the time, by the writer, to the State Department and various officials in Washington, was the first step in the long campaign that finally resulted in the establishment of the Hawaiian Islands Bird Reservation.

Gambier Shoal

Gambier Shoal is a circular atoll lying about half way between Midway and Pearl and Hermes Reef. The latter is an irregular oval atoll, about forty miles in circumference, which encloses a dozen small islets of shifting sand. It was discovered in 1822 by two whaling vessels, both of which were wrecked on the reef the same night within ten miles of each other, thus giving the reef its double name, and establishing a record for the locality that has served as a danger warning to mariners even to the present day.

Lisiansky, discovered in 1805 by a Russian, for whom it is named, is a small oval island composed mostly of coral sand. It is about two miles by three miles in extent and is surrounded by shallow water, but is without a central lagoon. Like Midway and Laysan, it has been visited by bird poachers from time to time. In 1905 a party of Japanese were found on the island engaged in killing birds for the millinery trade. It was estimated by the officers of the U. S. Revenue Cutter Thetis, who arrested the offenders, that they had killed three hundred thousand birds during the season.

Laysan

Laysan Island was an American discovery, made in 1828, and named by the captain for his vessel. It was taken possession of by the Hawaiian Kingdom and later proved to be a rich guano island. For years it was leased to a firm in Honolulu, which removed thousands of tons of valuable fertilizer from it. Laysan is about two miles long by a mile and a half in breadth. The writer has estimated that during the year 1902 it was inhabited by ten million sea birds that roam over the central north Pacific Ocean. This island differs from those previously considered in that it is unmistakably an elevated coral atoll, since it holds in its center a large briney lake, that has its surface slightly above the level of the sea that surrounds the island. The evidence seems to indicate that what was a low atoll at some remote period, possibly during the late Pliocene, was elevated and transformed, so that the atoll became a lake in mid-ocean surrounded by a ring of coral sand. The island is in turn practically surrounded by a coral reef with here and there an opening of sufficient size to admit a small row boat.

The harbor is on the southwest side and affords a safe anchorage in the lee of the island. The island has been more or less continuously inhabited for a number of years, and has been visited on several occasions by naturalists, so that its fauna and flora have been more fully studied and the island made more widely known than any of the other islands in the leeward chain. In another connection the remarkable bird population for which Laysan is justly famous has been referred to at some length.

The guano deposits have been very extensively worked and may now be regarded as practically exhausted. The beds were located on the inner slopes of the sand rim of the island at each end of the lake or lagoon. Originally they were from a few inches to two feet in thickness and varied greatly in the percentage of phosphate of lime—the valuable property for which they were worked. The bones and eggs of the birds whose excrement, in combination with the coral sand, formed the rich calcium phosphate or guano fertilizer, were often found in these beds in a semi-fossilized state, pointing to the way in which similar fossils have been embedded elsewhere in much older deposits.

The rate of deposition of this valuable fertilizer is necessarily very slow and is in direct proportion to the bird population. While it continues to be deposited, the amount is small as the colony has been seriously interfered with owing to the slaughter of the greater number of the large albatross, which doubtless have always been the chief factors in guano production in these waters.

Maro Reef was also the discovery of an American whaling ship in 1820. It is a rough quadrangular wreath of white breakers, about thirty-five miles in circumference, with no land in sight.

Dowsett Reef is but thirteen miles south of Maro, and like it. is evidently a young reef as compared with Laysan, since only a few rocks are awash here and there above the breakers. It was named for Captain Dowsett of the whaling brig "Kamehameha." whose vessel struck on the reef in 1872.

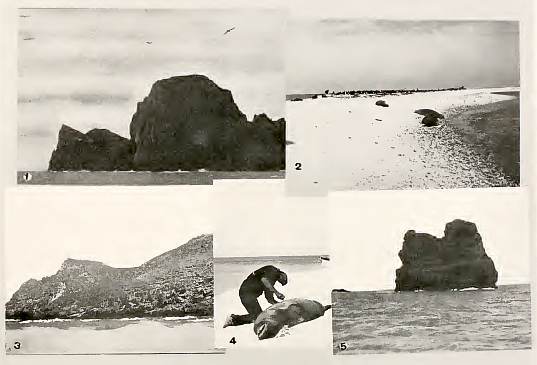

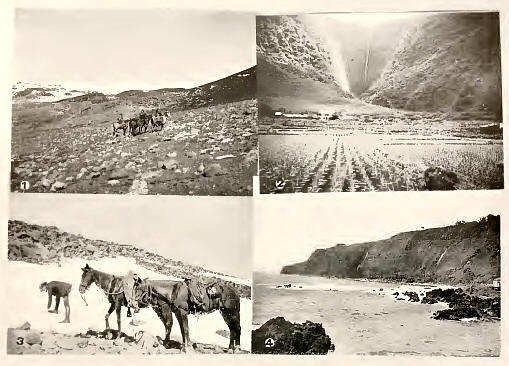

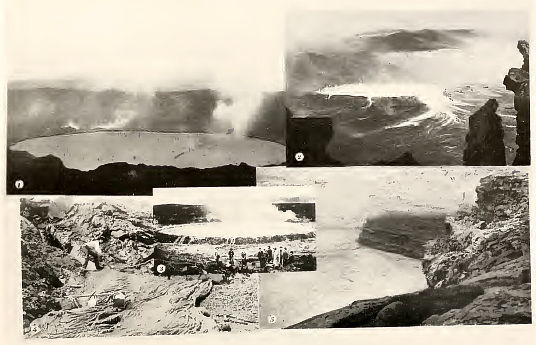

PLATE 21: REEFS AND ISLANDS IN THE LEEWARD CHAIN

1. Bird Island, Nihoa, (volcanic) from the northwest. 2. Seal on beach at Pearl and Hermes Reef. 3. Necker Island (low volcanic island) south side. 4. Skinning a seal on Pearl and Hermes Reef. 5. French Frigates Shoal (volcanic formation).

Gardner and French Frigates Shoal

Coming next to the second division of the leeward chain, we find, with the possible exception of Frost Shoal, which is thirteen miles southwest of Nihoa, that they are no longer wholly of coral formation. Gardner, the first of these islands, is a cone-shaped rock 170 feet high by 600 feet or more in diameter. There is a small island lying a short distance to the east of the main rock, but deep water comes up close to the main island on all sides, and vertical sea cliffs, sixty or seventy feet high, surround it on all sides. It was discovered by an American whaler in 1820, but has seldom been visited since. This is the first exposed evidence of volcanic rock to be met within the chain, and is of special interest, since it is more than 700 miles east and south of Ocean Island, and is at least 600 miles northwest of Honolulu. Such facts give the reader an idea of the magnificent distances one encounters in traveling through the length of the Hawaiian group. It also emphasizes the extent and magnitude of the chain of volcanic mountains submerged in the central north Pacific, of which, according to the legend of Pele's coming, previously related, and the opinion of learned geologists, only the tops of the tallest peaks are exposed.

The French Frigates Shoal is about thirty square miles in extent and was discovered by the great navigator La Perouse in 1796, and by him named for the two French frigates under his command. A striking volcanic rock, 120 feet high, rises from the lagoon, which is filled with growing reefs and shifting sand-banks. The surrounding reefs form a barrier about the volcanic point within and is perhaps the best example of this form of reef in the group.

Necker Island

Necker Island was discovered in 1786 during the same expedition that made the French Frigates Shoal first known to the world. It was named by the discoverer for the great French statesman and financier who convened the French States-General in 1781. The island, as shown by the steep sea cliffs, is the remains of a soil-capped volcanic crater, that is about 300 feet high, three-fourths of a mile in length, by 500 feet in width, at the widest part. It is surrounded by shallow water; there being an extensive shoal, principally on the south side.

This island and near-by Nihoa, or Bird Island, are of special interest as they were visited in ancient times by hunting and fishing parties from Kauai, who made the journey to it in their outrigger canoes. As Necker is 250 miles distant from the nearest inhabited island, the journey thither would seem to be one not to be lightly undertaken. But as the island was one of the few sources of supply of the coveted frigate and tropic bird feathers much used in their feather work, the journey seems to have been made more or less regularly.

The level portion on top of the island of Necker is more or less covered with a number of curiously formed stone enclosures, which may have been temples, in which have been found several remarkable stone images, fifteen inches or more in height. These, together with a number of curiously formed stone dishes with which they were associated, are now in the Bishop Museum. They are of such unusual design and workmanship as to make them appear relics of some race other than the Hawaiian. However, as the Hawaiian is the only race known to have visited these remote islands at so early a period, and as they were by nature a very religious people, there still remains the possibility that the relics, including the stone enclosures, if not of their making, were at least known to and probably made use of by them.

Nihoa

Nihoa completes the list of the leeward uninhabited islands of the Hawaiian group. It is 150 miles east of Necker and 120 miles northwest from Niihau, the nearest inhabited island. It is the highest island in the leeward chain, its summit being a pinnacle at the northwest end which rises 900 feet above the sea. The island is about a mile in length by 2,000 feet in breadth, which gives it an area of 250 acres. It is unmistakably the eroded remains of a very ancient and deeply submerged crater, the outer slopes of which have been worn away, leaving only a portion of the familiar, hollowed, volcanic bowl. The materials of which it is composed are similar to those of the high islands, and there is every evidence that it is even more ancient than Kauai.

Dr. Sereno Bishop, who visited it in 1885 as the geologist of a party, headed by the then Princess Liliuokalani, declared the island to be a pair of clinker pinnacles out of the inner cone of a once mighty volcanic dome, which has been eaten down by wind and rain for thousands of feet during unreckoned ages. From the large number of basaltic dikes which cut the island from end to end. he was led to infer that Nihoa is the result of an extremely protracted period of igneous activity. Perhaps this hoary remnant of the past may at one time have been a stately island, like those of the inhabited group with which we are familiar, that through submergence and erosion, has been reduced almost to sea level. Back to Contents

CHAPTER 9: The Inhabited Islands: A Description of Kauai and Niihau

Hawaii-nei: Position of the Inhabited Islands. The wonderful group of high, inhabited, volcanic islands over the formation, or at least the completion, of which the Hawaiians believed Pele presided, consists of the islands of Hawaii, Kahoolawe, Maui, Lanai, Molokai, Oahu, Kauai and Niihau, together with several smaller islands scattered about them. Taken collectively they form the Hawaiian group as it is generally understood, or as the natives expressed it, "Hawaii-nei," meaning all Hawaii. They are anchored far out in the middle of the north Pacific, under the Tropic of Cancer, and extend in a northwesterly direction from Hawaii, the southern most, to Niihau, a distance of about 400 miles. Honolulu, the capital and principal port of the Territory of Hawaii, is located on Oahu. The position of the Territorial observatory in the capitol grounds in Honolulu is in W. long. 157° 18' 0" and N. lat. 21° 18' 02", and is at a point about fifty miles north and west of the geographical center of the inhabited group.

Like most volcanic islands, the Hawaiian Islands lie in a more or less straight line; or to be more exact, in two nearly parallel lines, and are supposed by some to be superimposed over a great crack in the ocean's floor, and by others to rise from a submerged plateau.

Looking more broadly at the group in its relation to the rest of the world, we find the islands situated at the cross-roads of the Pacific Ocean, 2,100 miles southwest from San Francisco and eleven days' journey by the fastest train and ship, from New York. They are planted far out in the deep blue waters of the Pacific and are the most isolated islands in the world. It is twelve to eighteen thousand feet down to the ocean's floor on all sides of the group, and, as has already been said, it is believed that all of the islands are the exposed summits of gigantic mountains that rise more or less abruptly from the very bed of the Pacific Ocean.

This chain of fantastically sculptured volcanic mountain peaks, is made up of fifteen great craters, of the first magnitude, all of which at one time or another have been active. All but three of them. however, have been dead and extinct for centuries, perhaps thousands of centuries. Fortunately all three of the active volcanoes are located on Hawaii, the southernmost. and undoubtedly the youngest island of the group.

Since Honolulu is ordinarily the point of arrival and departure for trans-Pacific steamers, as well as inter-island boats, it is well to make it the center from which to study, in some detail; the main geographic, topographic and geologic features of the group.

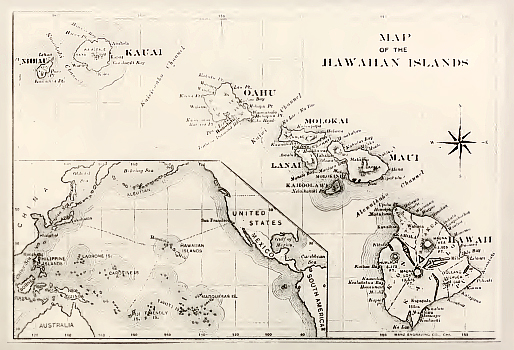

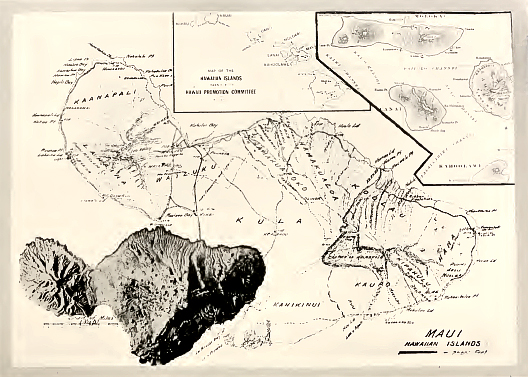

PLATE 22: MAP OF THE HIGH OR INHABITED ISLANDS OF THE HAWAIIAN GROUP

Niihau

To the northwest of Honolulu lie the islands of Niihau and Kauai. The former, the farther removed of the two, is in a northwesterly direction from Honolulu and is in line with the islands mentioned in another chapter as forming the leeward chain. It is seventeen miles west of Kauai from which it is separated by a very deep ocean channel. It is about eighteen miles long by eight miles in width, at the widest part, and has an area of ninety-seven square miles. The highest portion attains an elevation of about l,300 feet above sea level.

The island consists of a high central section called Kaeo, surrounded by a plain on three sides. On the north and west sides it is the highest and it is here that steep cliffs occur where the high land joins the summit flat. The higher part is irregular and of a basaltic origin, but is without the sharp peaks that characterize some of the larger islands. A large, natural pond near the center of the island and several smaller ponds and artificial reservoirs are found in various sections.

While Niihau shows evidence of great erosion it is evident that its moderate height and small size has prevented it receiving the abundant rainfall which has been an important factor in aging its larger companions.

A large part of the island is low, apparently of coral or aeolian origin, and is the inhabited section. The island is now utilized as a great sheep ranch, there being extensive areas of grass land, especially suited to grazing. Perhaps 150 natives, mostly comparatively new arrivals, now inhabit the island, and together with the old inhabitants, all told, are but a remnant of the thousand sturdy Hawaiians who made it their home less than seventy years ago. The island is noted in the group as the one on which is found the famous sedge from which the natives weave their serviceable soft grass mats, although the same plant occurs in suitable localities on all of the islands. The beaches are strewn with beautiful, though small, sea shells, known as Niihau shells, which are strung into long necklaces called Niihau leis.

Near Niihau are two cinder cones, Kaula on the west and Lehua on the northeast, which form small detached islands. Prof. Hitchcock says, '"The first is about the size and shape of Punchbowl, cut in two and the lower half destroyed by the waves. The concentric structure of the yellow cinders, much like the lower surface of Koko Head, is very obvious. Lehua appears to be a similar remnant, less eroded, as it has maintained about 200 degrees of its circumference instead of the 140 degrees of Kaula. Both these crater cones have the western or leeward side the hiuhest, because the trade winds drive the falling rain of ashes and lapilli in the direction of the air movement, building up a compact laminated pile of material to leeward. The subsequent erosion by the waves fashion a crescent-shaped island opening to the winds and surges upon the northeast side."

Kauai—The Garden Island

Kauai, next to the smallest of the five large islands, seems to agree with Niihau in age of formation. In fact, it is suggested that some great force has torn the smaller island away from the larger one without disturbing the strata of either. It is nearly circular and at the same time roughly quadrangular in form. Excepting the Mana flats, which seem to be uplifted coral reefs, the island could all be included within a circle, with a radius of fifteen miles, using Waialeale, the highest point, as the pivot. It is a beautiful, rich, well-watered island clothed with varied and luxuriant verdure and as such is often spoken of as the "Garden Island" of the group. Disintegration of the lava has proceeded farther here than on the other islands, a fact, taken in connection with other data, as indicating that the volcanic fires died out first at this end of the chain.

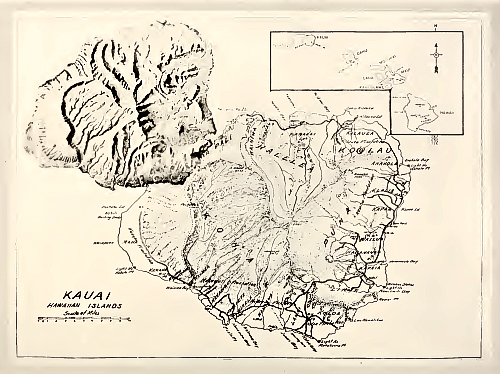

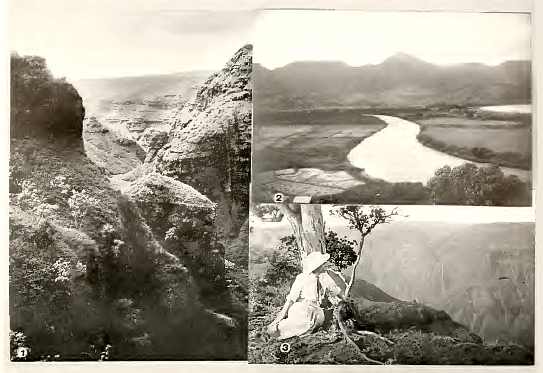

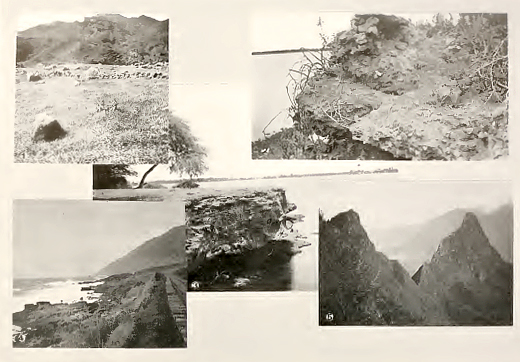

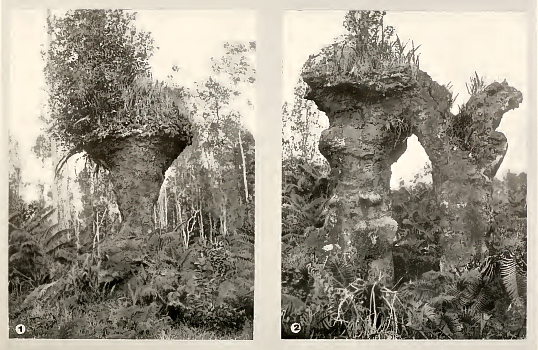

PLATE 23: VIEWS ON KAUAI

1. Wild mountain scenery along Olokele Cañon. 2. View from the mouth of the Wailua Stream. 3. The village of Hana-maulu. 4. Wailua Falls. 5. View along the east of Hanalei.

The coast is singularly regular in outline, there being no extensive bays or pronounced points or headlands. Except along the northwest side of the island, at Napali, where there are fifteen miles or more of picturesque sea cliffs, the coast lands are comparatively low and flat. The shore-line is free from coral reefs, presumably owing to the depth of water near the shore. In general the main contour of the island slopes rather gradually from the summit of Waialeale, at an elevation of 5250 feet, down to the sea, though ridges and corresponding valleys radiate spoke-like in all directions.

The eastern and northern side of the island, as is the case with all the islands, has been drenched by tropical rains for countless centuries with the result that erosion by wind and rain is most marked on that side of the island. The original slopes on the windward side of Kauai have been almost entirely eroded, leaving only a few short spur-like ridges. On the opposite or leeward side; however, the erosion is not so marked nor so far advanced, as the deep gorges with wide level spaces between them indicate. These gorges are deep and canon-like, inland, but, as they near the sea-coast, their sides become less precipitous and finally loose their character as the valley reaches the coastal plain.

Waialeale Mountain

Geologists agree that the central dome of Waialeale must have been much higher than now, and that the disintegrated lava has been washed from its summit to form the rich soil that makes up the coastal plain. The effects of erosion have been considered as perhaps the best evidence of the age of the Hawaiian mountains, and this great mountain worn to the core with its one-time lofty central crater eaten down to form a slimy bog on its summit, points to the great antiquity of the island under consideration. The gnawing action of wind and rain leaves only the more resistant ridges, as the old mountain is thus slowly eaten away. This has progressed on Kauai until only the skilled geologists can, in fancy, reconstruct its original dome-like outlines.

Everywhere in the group, but especially on Kauai, is found excellent examples of one-time solid rocks which are passing into fertile soil through the ordinary agencies of disintegration. In its earlier stages the new-formed soil is open and porous like a gravel bed. In this condition it absorbs large quantities of moisture which rapidly seep away from the surface. The power of lava soils to retain moisture varies with the mechanical state of the soil and the amount of organic matter it contains. While the soil under cultivation on Kauai is very fine, and for that reason retains water reasonably well, it is, in most cases, very red in color, indicating that it has not been discolored by the impregnation of vegetable acids, which in the forests and beds of valleys is very liable to produce a characteristic black soil.

PLATE 24: MAP OF THE ISLAND OF KAUAI

Lava Soil

Generally speaking the soil on Kauai is everywhere good, but is light and open, and requires much irrigation to make it fertile. The constant cultivation of the land does much to improve the soil, and by the addition of carefully compounded fertilizer and an abundant supply of water, enormous yields of sugarcane are secured. The growth of various crops affect the soil differently, as they remove from it varying amounts of nitrogen, phosphoric acid, potash and lime, which are the principal elements required by plants as food. Careful experiments have shown that the amount of these elements removed varies greatly even with the different varieties of cane that are grown in the islands. As a result, the care and proper fertilization of the soils of the group has been the subject of much scientific study.

While the main central dome on Kauai is the most conspicuous natural feature, there are other important elevations. The Hoary Head range, which extends down to the coast at Nawiliwili Bay, may be considered as part of the backbone of the main mountains. The highest point on this ridge, Haupu, is 2,080 feet; but between this point and the central dome the ridge is much lower, forming a pass for the Government road from Lawai to Lihue.

Secondary Volcanic Cones

A number of secondary volcanic cones on Kauai are important in the general topography of the island. The largest of these is Kilohana crater, which rises from the level Lihue plain to a height of 1,100 feet. The ejecta from this cone has been thrown over the country-side roundabout within a radius of four or five miles. In the neighborhood of Koloa are several small secondary volcanic cones within the radius of a few miles. The lava emitted by them was black and of a peculiar ropey type. Along the sea-shore the sea water forces its way under the surface and is often expelled through holes and openings in the lava in this vicinity. At favorable seasons the water spouts high in the air, forming great fountains termed "spouting horns.''

A great central forested bog, or morass, extends for miles along the top of the precipice which bounds the Wainiha Valley on the northeast. It slopes gradually to the southwest, and provides the nalural storage reservoir for the headwaters of the Waimea, Makaweli and Hanapepe rivers. This bog forms one of the least known, most dangerous and thoroughly inaccessible regions in the entire Hawaiian group. The writer, with an experienced native guide, spent three weeks in the region in the spring of 1900, and amid chilling rains and bewildering fogs, made an expedition extending through four days over miles of quaking moss-grown bog to a point designated by the guide as thesummit of Waialeale. We were never out of the dense fog during the expedition, and that we returned to our camp and to civilization at all has always seemed little short of the miraculous.

In many sections the thin turf, which covered the quagmire beneath, would tremble for yards in all directions at every step, and too often at a false step from the proper route, would give way, plunging us hip deep in the mire. Our chief concern was to locate reasonably solid ground, a necessary precaution that entailed many weary miles of wandering in the weird moss-grown wilderness, with attendant hardships and hazardous experiences that are still vivid in memory.

Cañons of Kauai

The numerous valleys and cañons of Kauai, and their attendant streams have justly been celebrated for their beauty and grandeur. Waimea is one of the finest, since it has cut its way between perpendicular walls which are several thousand feet in height at the head of the stream. The scenery along the Makaweli and Olokele cañons, tributaries of the Waimea system, and the Wainiha gorge, is the equal of the most rugged and magnificent mountain scenery anywhere in the world, and well repays the traveler for the effort made to view it.

PLATE 25: CAÑONS AND VALLEYS OF KAUAI

1. View in Olokele Cañon. 2. The Hanalei River. 3. View in Waimea Cañon.

The great Hanalei Valley, on the northern side of the island, is noteworthy for its scenery, its waterfalls and its stream, which is the largest river in the group, being navigable by small boats for about three miles. Wailua and Hanapepe are beautiful valleys, made more beautiful by their splendid waterfalls. Several of these streams, notably Hanalei, aiul the Hanapepe stream opposite it, give evidence of being drowned valleys, as in each case a broad intervale extends for a considerable distance inland.

The Napali Cliffs

The region of Napali, on the northwest side of the island, is difficult of access and, unfortunately, is seldom seen by the traveler. The section is given over by nature to a series of short, deep amphitheater-shaped gulches that show marks of profound erosion, leaving the region with some of the most awe-inspiring scenery on the islands. Returning from a cruise down the leeward chain, the writer had an opportunity to view the wonderful scenery of Napali at its best, from the vantage point of the deck of the vessel, at close range under the most favorable conditions. The late afternoon sun was lighting the bold headlands and the fantastic fjord-like valleys—in a way to accentuate every detail of the singularly charming and beautiful panoramic view. The splendor of Kalalau valley, the largest and perhaps the most wonderful of them all—a valley of grandeur, golden light, purple shadows, and sunset rainbows—was a welcome change after the daily monotony of the open sea on a long, lonely, though happy voyage.

The Barking Sands

Among the natural features of Kauai of considerable geologic interest should he mentioned the barking sands of Mana. They consist of a series of wind-blown sand hills, a half mile or more in length, along the shore at Nahili. The bank is nearly sixty feet high and through the action of the wind the mound is constantly advancing on the land. The front wall is quite steep. The white sand, which is composed of coral, shells and particles of lava, has the peculiar property, when very dry, of emitting a sound when two handfuls are clapped together, that, to the imaginative mind, seems to resemble the barking of a dog. When a horse is rushed down the steep incline of the mound a curious sound as of subterranean thunder is produced. The sound varies with the degree of heat, the dryness of the sand and the amount of friction employed; so that sounds varying from a faint rustle to a deep rumble may be produced. Attempts at explaining this rare natural phenomenon have left much of the mystery still unsolved. However, the dry sand doubtless has a resonant quality that is the basis of the peculiar manifestation, which disappears when the sand is wet. That the barking sands are found in only a couple of the driest localities in the group is also significant. Much of the shoreline of Kauai, for example, is lined with old coral reefs that have partly disintegrated into sand that forms the beaches. This sand, as aeolian deposits, is often carried inland for considerable distances, and though composed of the same material, it has none of the peculiar qualities of the sand at Mana.

Spouting Horn—Caves

The blow hole, or spouting horn, is a familiar natural curiosity fairly common in the islands. Famous ones at Koloa, mentioned above, have long been objects of interest to travelers. At half-tide, particularly during a heavy sea, the larger ones throw up fountains from openings five feet in diameter, that often rise as a column of water and spray fifty or sixty feet in height. The sound of the air as it rushes through the small crevices is most startling to the spectator, who feels the rocks beneath his feet tremble as shrill shrieks and various uncanny noises are produced by the wild rush of the water into the cave below him. These caves are usually bubbles in the lava stream, or sometimes they are formed by the washing away of the loose pieces of rock underlying the more solid outer crust of the old lava flow. The caves in the cliffs of Haena are among Kauai's numerous places of geologic interest. Two of these are at sea level and are filled with water. In one the water is fresh, in the other it is salt. In many places the roof of the caves are encrusted with mineral deposits, sometimes several inches in thickness. The lower caves can only be entered at certain tides and under favorable conditions. However, they are known to be old lava conduits and evidently extend back into the cliff for some distance.

In several places in the group, but notably in Hanapepe Valley, columnar basalt occurs. These curious prisms are from ten to eighteen inches in diameter with sides from five to seven feet in length. They are rude six-sided columns which appear to be due to the peculiar contraction of the lava, usually under pressure, as it cools. Back to Contents

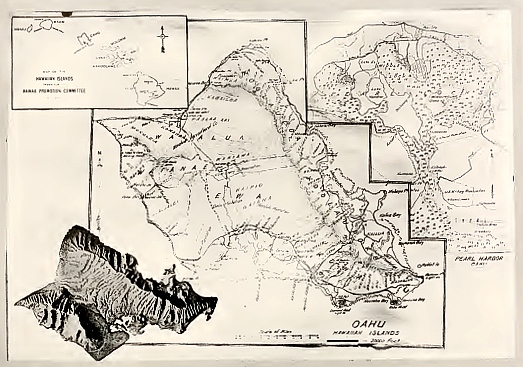

For obvious reasons the formation of Oahu, the metropolis of the group, has received much attention from various observers, with the result that its topography and geology are better known than is the case with any of the other islands.

A Laboratory in Vulcanology

Only a few of the more striking physiographic features of the island can be referred to here, but it is a fact that on Oahu the student of natural phenomena has a veritable open-air laboratory in vulcanology, stored with splendid specimens, showing practically every phase that results from volcanic activity and erosion.

Oahu is about fifty-four miles long by twenty-three broad in its greatest right angle dimensions. It has an area of 5,985 square miles, with a coast line of 177 miles, and has its highest mountain peak 4,030 feet above the sea. In outline it forms a four-sided kite-shape figure in which the four points might be said to correspond, in relative position, to the stars in the Southern Cross. Kaena, the northwest point of the island, is at the top of the cross; Makapuu, the southeast point, is at the bottom. Kahaku Point, at the northeast, and Barber's Point, at the southwest, correspond with the right and left hand stars in the astral figure. The shore-line of the island which connects these four main points is more irregular in outline than that of any other island in the group, a fact which has given to Oahu its valuable harbor facilities.

PLATE 26: MAP OF THE ISLAND OF OAHU

Honolulu Harbor—Pearl Harbor

Beginning with Honolulu Harbor, situated at the mouth of the Nuuanu stream, and about midway along the southern side of the island between Makapuu and Barber's Point, we find the most important harbor in the group. It is formed by a sight indentation of the coast-line and is protected by a coral reef that extends across the exposed sea-side. Through the reef an entrance has been kept open by the waters from Nuuanu and the adjoining stream, which, being fresh, prevents the growth of the coral. This natural entrance to the harbor, which has since been deepened and strengthened, was taken advantage of by the natives and by foreign vessels that visited the islands until, in time, the village on the shore grew into a prosperous city. The harbor derived its name not from the harbor itself, but from a small district along the Nuuanu stream a mile from the mouth—"a district of abundant calm," or "a pleasant slope of restful land," that received its name in turn from a chief called Honolulu, whose name was formed by a union of two words, 'hono,' abundance, and 'lulu,' peace or calm; hence to speak of Honolulu as a haven of abundant peace and calm is but to transfer to the harbor a poetic descriptive name derived from the adjacent land.

Along the coast a few miles to the west is the entrance to Pearl Harbor, which is an enclosed body of water made up of two main divisions, known respectively as East and West Lochs, the latter being much the larger of the two. They combine to form a channel which also carries fresh water sufficient to keep open a passage, through the protecting coral reef, to the sea. This great landlocked harbor is now being developed by the Federal government, by dredging and fortifying its channel, with a view to making of it a great naval base for the United States, as well as the finest and safest harbor in the Pacific. On the opposite or windward side of the island are located Kaneohe Bay and Kahana Bay, both with extensive coral reefs across their mouths. The former, a large, beautiful sheet of water, is partially enclosed on one side by Mokapu Point, and on the other by Kualoa headland, but unfortunately it is filled with submerged coral islands, rendering it inaccessible except to small vessels. Waialua Bay, on the northwest shore, while formed by a pronounced curve of the coast-line, is in reality little more than an open roadstead where small coasting vessels can anchor and find shelter from the northeast trades that have full sweep down that coast. Other beautiful bays of much geologic interest and significance occur at various points. Among them should be mentioned Waimea, a few miles beyond Waialua, Laie and Kailua bays on the windward coast, and Hanauma and Waialae bays between Honolulu and Makapuu Point on the south coast.

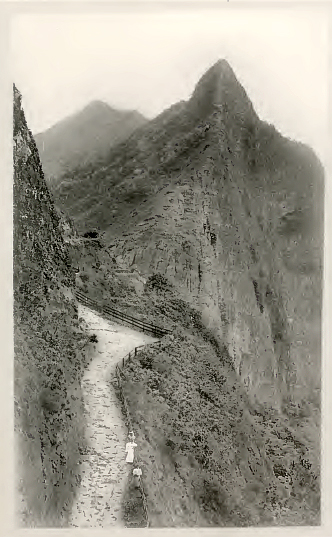

PLATE 27: VIEW IN NUUANU VALLEY NEAR THE PALI SHOWING THE PEAK OF LANIHULI

The Koolau and Waianae Mountains

Turning to the land itself we find the island formed by the union of two nearly parallel mountain chains. The Koolau Range stretches for thirty-seven miles along the northeast or windward side of the island and, extending from Kahuku to Makapuu points, forms the longest range of mountains in the Hawaiian group. Along the southwest side extends the Waianae Range, which is about one-half the length of the range along the opposite side of the island.

Without doubt, the Waianae Range is the older of the two, and with Kaala, the highest point on the island, as its central figure, the range furnishes topographic features of prime importance. Geologists believe this group of mountains to correspond in age with the central dome of Kauai and that an enormous amount of erosion has left but the skeleton of a vast dome that was much higher and more symmetrical than its time-scarred outline would now suggest.

It is thought that it was long after the Waianae Range was formed as a separate island, before the Koolau Range began to build itself up above the sea to form an annex, as it were, to the original island which had Kaala as its center. Thus, according to Dana and other geologists, Oahu was formed as a volcanic doublet—the work of two volcanoes whose adjacent sides, by lava flows and by erosion, have been united in the plains of Wahiawa, but whose forms have been so eroded that the exact position and extent of their craters has not been indicated with certainty.

The Pali

The magnitude of the second crater is perhaps best appreciated from the historic landmark and pass through the Koolau Range known as the Pali, a word signifying in Hawaiian, a steep precipice. The Pali is approached from Honolulu by a road five or six miles in length that winds up the floor of Nuuanu Valley until at an elevation of 1,207 feet, with the peak of Lanihuli (2,275 feet), on the left, and Konahuanui (3,103 feet), the highest peak in the Koolau Range, on the right, it suddenly ends in a vertical drop of 700 feet. Several miles of almost vertical basaltic cliffs,—the eroded walls of this vast crater—stretch away on either hand. The Pali is truly Oahu's scenic lion. It is a natural wonder, that as a genuine surprise has nothing to equal it in all the world. From its sheer edge, the splendid panoramic view of the windward side of the island is spread out at the observer's feet—a view of rugged mountains, of cliffs, of country side, of quiet bays, of coral strands, and of the open sea that has beggared the descriptive powers of the most gifted.

Here the observer comes to appreciate not only the stupendous constructive power of nature that has called the island into being, but also those destructive agencies which, through countless centuries have been tearing down the solid rock, disintegrating, transporting and distributing it according to well-established natural laws. With its long, vertical crater wall standing abreast of the northeast trade winds, and with the elevation and other conditions favorable to bring about an abundant rainfall, the Koolau range, on the leeward side, especially, has been furrowed from end to end into a series of deep lateral valleys, separated from each other by nearly parallel ridges that are conspicuous and significant features of the general topography of the island. The larger and more important of these valleys and ridges have a general southwesterly trend. The streams which rise in the section between the Koolau and the Waianae chain, however, are deflected by reason of the high plateau at Wahiawa so that part of them enter the sea at Waialua, while others join in the Ewa district of the island and find their outlet to the ocean through the great Pearl Lochs already mentioned.

The windward side shows plainly the full force of drenching rains and the cutting winds. For the seaward surfaces are everywhere deeply eroded and the disintegrated lava removed, leaving a series of amphitheaters, narrow promontory-like outlying ridges and cliffs that mark the more resistant cores of the solid rock.

The erosion of the Kaala dome is not so easily understood since the greater excavations are on the west side, while the slopes which are to windward, that is towards the Koolau range, are more gradual. But as the Waianae Mountains are conceded to be much older than the opposite range, it is presumed that the conditions which exist now are much modified from those that were in effect when the Waianae Range was first eaten down.

PLATE 31: NUUANU PALI

1. Nuuanu Pali from the road on the windward side looking back towards Lanihuli peak (2,275 feet); on the left of this road is Konahuanui (3,103 feet). The Pali is of great geologic, historic and scenic interest.

Smaller Basaltic Craters and Tuff-Cones

While the main ranges already discussed are of first importance in the topography of the island, the later volcanic manifestations, especially of the series of basaltic craters and tuff-cones that mark the close of volcanic activity on Oahu, form striking objects in the general contour of the island.

The tuff-cones are the most numerous and conspicuous, several being in view from Honolulu. Of these Diamond Head, or Leahi, the famous landmark often spoken of as the sphinx of the Pacific, is the most noticeable. As the traveler approaches the island for the first time Diamond Head with its imposing, rugged outline is sure to attract attention; often, too, it is the last parting glimpse of Diamond Head from the distance, as the voyager leaves the island behind, that brings the full realization to mind of all that it typifies of the life in a tropic land that has so fascinated him that, wander where he will, Oahu's shores seem always to call him back again.

PLATE 28: WAIKIKI BEACH AND DIAMOND HEAD

Waikiki beach is one of the finest bathing resorts in the world. Besides being of interest to geologists, the reef which stretches from the month of Honolulu Harbor to the point of Diamond Head is a splendid collection ground for the marine zoologist. Examples of almost all of the great orders of marine animals occur at Waikiki. These may be seen alive and , in most cases, be taken from the shallow waters on the reef or from the sand beach.

Diamond Head

Diamond Head rises in bold relief from the shore-line beyond Waikiki, to the height of 761 feet. While its sharp outline may seem to suggest to some the appropriate and accepted popular name by which the point is known far and wide, the name was, in fact, derived from the excitement created through the discovery by sailors at an early day of small calcite crystals that they thought to be diamonds.

This crater mountain looks from the outside to be solid rock, but in reality it is a great hollow oval tuff-cone, 4,000 by 3,300 feet in its diameters, with its elongation in the direction of the trade winds. Owing to the ejecta being carried by the prevailing winds when the crater was in eruption the southwest side of this and of similar cones on the island is considerably higher than is the opposite side. Inside the crater the walls slope gently to the center, where, near the eastern wall, during the wet season, there is, or at least there was, a small fresh water lake, 200 feet above the sea, that was frequented by wild fowl at the proper season.

Dr. Sereno E. Bishop made Diamond Head the basis of a study calculated to show the brief time required for the completion of tuff-cones of similar form. He concluded that such a cone "could have been created only by an extremely rapid projection aloft of its material, completed in a few hours at the most, and ceasing suddenly and finally." Taking into account the extreme regularity of its rim and the uniform dip and character of its crater he proceeded, with a mathematical calculation, to estimate that the 13,000,000,000 cubic feet of material that forms its mass could have been raised to approximately 12,000 feet, and dropped into its present position in two hours' time, and he was inclined to increase the velocity of the ejecta and reduce the time to perhaps one hour Other geologists, however, are very likely to question the soundness of the conclusions drawn by Dr. Bishop since there is unmistakable evidence that it was in eruption a number of times with intervening periods of repose.

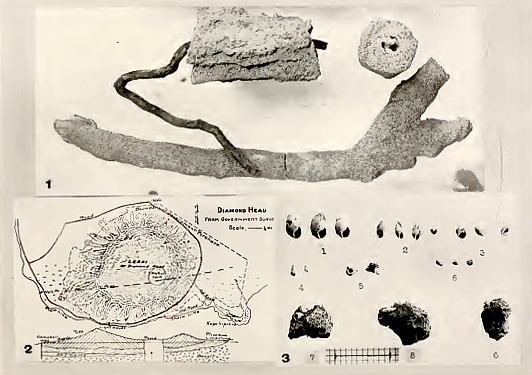

PLATE 29: SPECIMINS FROM DIAMOND HEAD

1. Roots encrusted with sand forming root casts. 2. Vertical section and plan map of Diamond Head. 3. Fossil shells from the slopes of Diamond Head crater.

Punchbowl Hill

Punchbowl Hill, with a form which suggests its name—lies just back of the city and is 498 feet high. It is similar to Diamond Head in form and structure and has in its outer wall on the town side, numerous seams filled with calcite. Much can be learned of the geology of the vicinity by the study of the cone itself and from the phenomena about it. Other tuff-cones are Tantalus, Salt Lake, and Koko Head; there are still others on the opposite side of the island at Kaneohe, as well as at the south end of the Waianae mountains at Laeloa. Some of the cones in the latter region, however, are small basaltic craters, as are also the one on Rocky Hill in Manoa Valley, and the two small craters, Muumai and Kaimuki, on the ridge back of Diamond Head, to the east of Honolulu.

Elevated Goral Reefs

Almost the entire shore-line of Oahu shows more or less evidence of elevated coral reefs. In the vicinity of Honolulu these reefs form the foundation on which much of the city it built. The elevated reefs are most extensive, however, in the vicinity of Pearl Lochs, where they are intimately associated with the sedimentary deposits, volcanic flows, decaying rock and volcanic ash. It is thought by Professor Hitchcock and others that this series of deposits began in the Pliocene period and that it and the older layers beneath may be a base on which the ejections that formed the volcanic island began to accumulate. The region about Pearl Harbor is one of much geologic interest, but is far too complicated in character to be readily interpreted by the casual visitor. Features of general interest, however, are that in many places as many as nine or ten stratified deposits may he seen in a vertical cut of forty or fifty feet, and that in the region, beds from one to three or four feel thick, of large oyster shells (Ostrea retusa) are exposed, far inland. According to the investigations of Professor Hitchcock, "the Pliocene area of Oahu coincides very nearly with the low land tract utilized for cane and sisal from Barber's Point to Koko Head; perhaps to the altitude of 300 feet entirely around the island." Small patches of the rock appear at Waianae, Waialua, Kahuku Plantation. Laie and other places on the northeast coast, the highest reef being on the southwest end of Mailiilii at 120 feet above the sea. The rock is also extensively distributed beneath the surface, as is developed in boring- artesian wells.

Age of Oahu

Dr. W. H. Dall, who also studied the deposits in the vicinity of Pearl Harbor and Diamond Head, found species of sea shells seemingly extinct, which are referable to the Pliocene. In conclusion he says, "that the reef rock of Pearl Harbor and Diamond Head limestones, are of the late Tertiary age which may accord with the Pliocene of West American shores or even the somewhat earlier, and in the region studied there was no evidence of any Pleistocene elevated reefs whatsoever. It is probable that Oahu was land inhabited by animals as early as the Eocene," which period preceded the Miocene, and marked the opening period of the Cenozoic era, or the era of modern life.

Black Volcanic Sand

Over much of the region about Honolulu, but especially on the slopes of the Punchbowl and Tantalus group of cones, are to be found extensive deposits of black ash, a volcanic product usually formed from basalt when erupted in association with much steam. The maximum thickness of the deposits is exposed at the base of the Tantalus cone, in Makiki Valley, where a bed twenty-five feet thick occurs. This coarse-grained sand has found many uses in the city; such as in making sidewalks and grading roads, and to some extent as sewers in the early days, while recently it has been found to be of some value as a fertilizer owing to the presence of potassium. The sources of the deposits referred to seems to have been Tantalus and Punchbowl; but practically all of the smaller cones have given more or less volcanic ash, which varies in fineness and color, as well as in amount, in each eruption and at different times during the same eruption. On Punchbowl especially this ash overlays the tuff, and, owing to the pronounced weathering of the latter, it seems to indicate two quite distinct periods of activity from the same source, with a long period of time between them. In the first eruption the material came up through the sea as the character of the tuff deposits indicate, while the later eruption or eruptions, including the ash, the basalt-like dikes which radiate from the rim, as well as the cinder-like beds on the upper part of the rim, found its way up a pipe within the cone from a deeper source of basalt, apparently without coming in contact with the water of the sea or its limestone deposits.

Limestone is also abundant about the crater at Diamond Head, at Koko Head, and at the Salt Lake crater, where portions of the old reef are said to be present on the inside of the crater.

A matter of considerable interest has been brought to light through the excavations and road-cuttings about the base of Diamond Head, and especially at the quarries and sand pits opened there. The material of the lower slope is a talus made up of angular fragments from the slopes above, which is cemented into a brecciated mass, showing clearly that none of the angular particles have been rounded against each other, or by the action of water. In this mass have been discovered the remains of land shells of several probably extinct species belonging to well-known genera. Dr. Hitchcock concludes that the talus breccia at Diamond Head must be much newer than the date of the eruption of the tuff, since it is composed of fragments of that material from the older eruptions that are cemented together in the more recent talus. Considerable time must have elapsed between the ejection of the older material and the presence of the shell-bearing animals because the rocks must have been decomposed sufficiently to admit the growth of some vegetation on which the mollusks could live. From observations made in the same vicinity, and data gathered elsewhere about the island, but principally from the remains of the marine shells distributed inland over its surface, the same authority concludes that the whole of the island of Oahu must have been subsequently submerged for a brief period to a depth of two to three hundred feet, presumably during the Pliocene period. If so, it is concluded that the time of deposition of the land shells, found at the foot of Diamond Head, will be fixed at a period sufficiently remote to admit enough time to have elapsed since then to account for the development elsewhere on the island of the related and varied forms of land and tree shells^ which, as we shall find in another chapter, have been much studied by many zoologists, but especially by the world-renowned evolutionist, Dr. John T. Gulick, whose pioneer work in that important field of science has added so much that is fundamental to our understanding of the great laws of organic evolution.

Geologic History of Oahu

In the preceding pages only a meager outline of the written evidence touching on the more salient points in the geologic history of Oahu has been attempted. Enough of the wonderful story has been given, however, to make it appear that the island was not in existence in its present form at the beginning, nor was it thrown up in its present form in a single mighty titanic convulsion of nature.

Let us review in their apparent natural order, some of the important chapters in nature's history of Oahu, for the facts which tell of the hoary events resulting in the formation of this wonderful island, with its charming scenery, are all written in stone, as it were, and may be read by those with skill and patience to decipher.

In the beginning, the long Pacific Ocean swells doubtless rolled without interruption over the place where the island now stands. Just how long this condition lasted we can never know, but the evidence seems sufficient to Professor Hitchcock and others to warrant the conclusion that deposits of the Tertiary, perhaps the Eocene period, form the foundation on which the volcanic mass of the original island of Kaala was formed. These eruptive deposits began to be laid down under water, but in time the cone of Kaala built itself above the ocean perhaps three thousand feet higher than the tallest peak of the Waianae Range as we know it today. In reality the range is but the remains of a great dome, more or less symetrical, that at first arose above the waters. By the erosive action of copious rains brought then as now from over the sea, it was deeply eaten away on all sides until its ancient form was very nearly effaced. During this period it slowly accumulated a stock of plants and animals from other regions, partly from other islands near and far and partly from the distant continents about the ocean.

Subsequently the island which may be called Koolau, only twenty miles to the north, was developed in a succession of eruptions, much as Kaala had developed before it, until its lavas and the soil eroded from them banked up several hundred feel about the foot of the older adjacent island-mountain, uniting the two islands into one and forming the plain of Wahiawa. It is asserted that Koolau extended farther northeast than at present and that the active center of the crater must have been beyond the foot of the Pali.

As soon as conditions became favorable, limestone began to form as coral reefs, probably first about the older island and later about them both. It has continued to be formed to the present day through the various chemical, physical and geologic agencies. Artesian well borings and other sources of information have revealed data to prove that during this immensely long period the surface of the island stood much higher than at present.

The Pali crater and a doubtful crater near the head of Nuuanu Valley give evidence of periodic activity during this time, such as the eruption of the cellular or viscular lava, the formation of olivine laccoliths, and the intrusion of dikes of solid basalt that filled in fissures in the older mass. The last evidence of activity at the Pali appears in the form of an eruption of ash, clinkers and lava.

About this time Kapuai and Makakilo craters in the Laeloa region at the east end of the Waianae Range, and perhaps one or more of the Tantalus craters, were formed. Then came the ejection of some of the lavas met with in the sinking of artesian wells and the formation of certain of the Laeloa craters, also those at Kaimuki, Manumai, and perhaps Rocky Hill, though Dr. Bishop places the eruption of the solid basalt which completely blocked the mouth of Manoa Valley at a much earlier period; but as its lower end extends a short distance over the elevated reef at Moiliili, Rocky Hill must have been in eruption after the reef was formed.

Next came the period of the eruption of the tuff craters: the Salt Lake group, Punchbowl, Diamond Head, Koko Head, the Kaneohe group and other smaller craters of similar character. During this period the tuff came up through coral reefs, the land as we know it being submerged in the region of eruption. Then followed a long period of decay and the disintegration of the older eruptions and the newer tuff-cones of sufficient duration to produce soils from them. This period culminated in the discharge of ashes from Tantalus, Punchbowl, Diamond Head, Koko Head and other members of this group of craters, which terminated usually in a more or less extensive shower of volcanic stones. Dikes were then intruded into crevices, cutting Punchbowl, Diamond Head, and the coral reefs at various points, notably at Kaena Point, Kupikipikio and Koko Head.

Time then elapsed for the accumulation of ealcarious talus breccia with soil and vegetation on the lower slope of Diamond Head sufficient to support several species of land shells. Then apparently came the depression of the whole island during which time the ocean encroached on the land above its present level, submerging the low lands about the island. This comparatively brief period left ocean deposits and slight wave markings about the new shore line, which, when the island was again elevated to its present level, was marked by ocean-flooded sand dunes—over which more recent dunes have been piled by the action of the wind. Lastly comes the long periods of disintegration, the formation of surface soil and finally human culture. While geologists may disagree, and there is much ground for disagreement, in the interpretation of the records in minor matters, all are agreed in the main points, and freely state that almost inconceivable time has elapsed since the oldest part of Oahu first emerged as a volcanic island.

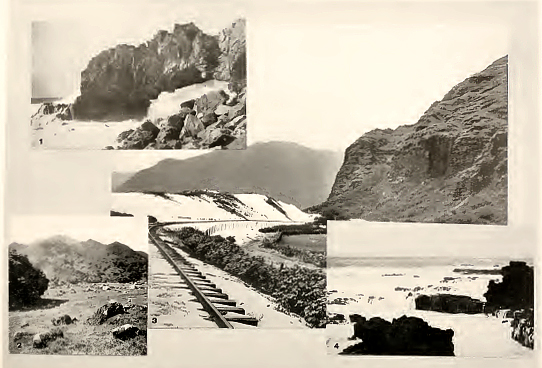

PLATE 30: SCENERY ON OAHU

1. The natural bridge at Makaloa. 2. Waianae mountains from the railway. 3. The barking sands near Makua Station. 4. Surf along the coast near Kaena Point.

Theory of the Formation of the Group

Among the various theories that have been advanced in attempts to reconstruct the past history of the group, one of great interest and significance has recently been brought forward, in a very concrete form, by Dr. Henry A. Pilsbry, that has as its basis an exhaustive study of the Hawaiian land shells.

He finds this interesting portion of the fauna belonging chiefly to a branch of a very ancient group of land mollusks that are distributed on various islands of the Pacific. As there is a marked absence of modern types of land mollusks—save those that have been introduced through commerce—he feels that the peculiar fauna cannot be considered as springing from accidental introduction in the group from time to time in the remote past. By analogy the conclusion is arrived at that "the Achatinellidae had already differentiated as a family before the beginning of the Tertiary." But the close relationship of the genera of the sub-family Amastrina and the even closer relationship of the genera of the related sub-family Achatinellina "indicate a sudden rejuvenescence of the old stock in comparatively modern time." A study of the species, varieties and forms extant show that everywhere intense local differentiation is still in progress.

Dr. Pilsbry concludes that "the logical geographic boundaries of most of the species of Achatinellida give excellent ground for the belief that the present distribution of all the larger species has been attained by their own means of locomotion and that unusual or so-called accidental carriage, as by birds, drifting trees, etc., has been so rare as to be negligible. No evidence whatever of such carriage is known to me."

After exhausting the possibilities of accidental introduction of species from island to island, the conclusion follows that all of the important islands must have been, at one time, connected by land, and that distribution of the ancestral forms of land shells from Kauai to Hawaii was effected at that time.

As the Hawaiian chain, from Ocean and Midway Islands to Hawaii, a distance of 1,700 miles, rests on a submarine ridge, the greatest depth between the islands being less than 3,000 fathoms, the distribution and subsequent isolation of the forms on the islands appear to be in accord with the theory of subsidence of the ridge supporting the entire archipelago after wide distribution of the land forms had taken place.

From the affinities and the geographic relations of the several groups of hind shells studied, our authority deduces the following sequence of events, the beginning of which is placed probably in the Mesozoic, possibly in Eocene time.

1. "The Hawaiian area from northern Hawaii to and probably far beyond Kauai formed one large island which was inhabited by the primitive Amastrina. This pan-Hawaiian land, whatever its structure, preceded the era of volcanism which gave their present topography to the islands and probably dated from the Paleozoic."

2. "Volcanic activity built up the older masses, subsidence following, Kauai being the first island dismembered from the pan-Hawaiian area."

3. "Northern Hawaii was next isolated by formation of the Alenuihala Channel, leaving the large intermediate island, which included the present islands of Oahu, Molokai, Lanai, and Maui."

4. "In the eastern end of this Oahu-Maui island arose certain genera, while another peculiar genera was evolved in the west from undoubted ancestral stock.

5. "The Oahuan and the Molokai-Lanai-Mauian areas were sundered by subsidence of the Kaiwi Channel." On Oahu the mollusean fauna bears out the generally accepted theory of two centers, probably two islands, the western or Waianae and the eastern or Koolau area. In each area, certain genera were differentiated, but later, in the later Pliocene or Pleistocene time a forested connection was established forming a faunal bridge which admitted of the mingling of the two island faunas. While the land connection endures, the forest has, in recent time, become extinct and thus the two centers are again isolated so far as forest-loving snails are concerned.

Turning to the eastern or Molokai-Lanai-Maui region, it is Dr. Pilsbry's opinion that the close relationship of their fauna indicate that they formed a single island up to late Pliocene or even Pleistocene time. The formation of the channels between Molokai, Lanai and Maui must be considered as a very recent event since they stand on a platfonn within the 100 fathom line and their faunas are very closely related.

The investigation of the island fauna and flora as conducted by various observers has brought out facts of evolution that seem in full accord with the dismemberment of the various islands as here described.

In addition to all else, the evidence of the wonderfully dissected mountains, the deeply eroded valleys, the submerged coral reefs all tend to bear out the broad conclusion that the group has evolved by the submergence of a single island, and that the isolation of the existing islands, with their peculiar, yet related plants and animals, have been formed as superimposed volcanic remnants on the older and deeply subsided larger land area.

Dr. Sereno Bishop, discussing the geology of Oahu, tentatively offered an estimate of the length of time that must have elapsed since the successive events in the geological history of the island took place. Such estimates of geologic time must of necessity be accepted only as individual guesses and the personal factor taken into account, but they have their value for those less skilled, enabling them to form a rough chronology that the mind can in a measure grasp. While scientific guesses of this nature are valuable, they are liable in each instance to fall far short of the actual time involved. Dr. Bishop's table places the time of the emergence of the Waianae Range as a volcanic mountain at one million years ago. The emergence of the Koolau Range is placed at eight hundred thousand years ago, and the extinction of the Waianae activity one hundred thousand years thereafter, while the extinction of the Koolau Range is placed five hundred thousand years back in the past. The emergence of Laeloa craters and Rocky Hill are both placed at least seventy-five thousand years ago. The time of the eruption of Punchbowl is given as forty-five thousand years ago: the small Nuuanu craters twenty thousand; Diamond Head fifteen thousand; Kaimuki twelve thousand; the Salt Lake group ten thousand; Tantalus, seven or eight thousand, while the eruption of the Koko Head group, the last of the important tuff-cones to be formed, is given as occurring but a meager five thousand years ago. The author, however, is inclined to attribute a very much greater age to Oahu than that indicated by Dr. Bishop. The foundation for such a belief is based largely on a careful physiographic study of the Waianae Mountains. It seems obvious that the deeply eroded valleys of the Waianae Range were practically completed as they are now before the slight re-elevation of the island brought the ancient reefs above the sea. These elevated reefs contain extinct fossils, probably those of Eocene time. The dawn of the Eocene is generally placed by geologists at four million years ago. How much older then must be the mountain mass in which the valleys of the Waianae region were so deeply carved before the reefs were laid down across the embayments at the mouths of their valley streams?

Artesian Wells

Reference has been made above to the artesian water supply of the island, and the important geologic facts that the sinking of five hundred or more artesian wells on Oahu has brought to light. The wealth of water, amounting to millions of gallons per hour, now poured out on what was formally in many places semiarid, and therefore, unproductive land, has been the prime factor in the modern development of the agricultural resources, not only on the island under consideration, but all the islands of the group, where conditions favorable to the development of artesian wells are found.

The erosion of the sloping volcanic lava flows in the mountains offers conditions favorable for storing in the ground much of the excess of the copious precipitation occurring in the higher altitudes. As we have seen, the strata of igneous cock exposed in the mountains are often buried several hundred feet beneath the surface when they reach the costal plain. The water which enters the exposed portion of the more porous strata, especially when the water-bearing strata lie between more impervious strata, tends by gravity to flow as underground water down to the lower levels. Eventually, this underground stream descends to the sea, often several miles distant from the point in the highlands where it was taken into the porous rock or soil.

If the lower ends of the water-bearing strata open into the sea beneath its surface, the fresh water gradually forces its way out at the lower end of the natural conduit, to mingle quietly with the water of the ocean, or, as often occurs about the shore line of the group, to bubble to the surface forming fresh water springs in the ocean.

Owing to the pressure exerted by the sea, the subterranean water moves out much more slowly than the surface water which rushes from the mountains to the sea in the form of rivers. If the pressure of the water in the underground stream is greater than the pressure exerted by the water of the sea, the stream continues to flow into the latter as fresh water. If the pressure of the ocean exceeds that exerted by the underground waters, the two waters commingle, and brackish water occurs in the underground basin. So long as the fresh water level in the underground stream or basin is maintained at a level above sea-level, the water in the underground stream or basin seems to remain free from salt.

An appreciation of the geologic conditions existing in the strata of rock underlying the island, and the need of a more abundant water supply, led to the practical utilization of this great natural resource through the development of artesian wells. The first well was sunk in 1879 by James Campbell on an island in Pearl Harbor and fresh water was secured at a depth of 240 feet. The natural principle involved in the fresh water spring and especially the spring in the ocean, was turned to practical account. To secure water, wells were driven deep enough into the earth to puncture the more or less impervious strata overlying the water-bearing strata beneath, with the result that owing to the pressure or head on the empounded water, it rose in the well, and in the lower zone about the island often overflowed to form an artificial spring or flowing artesian well. The principle involved in wells which do not overflow is the same as that in those that do; for which reason all deep wells are now called artesian. Wells in which the water is raised to the surface in pumps are liable to become brackish, through excessive pumping, while those which flow naturally seldom show a marked change in the amount of salt carried in their waters.

The water bearing stratum on Oahu at the sea-shore, is usually found to be between three and four hundred feet below tide level, and is usually a very porous basalt, capped with an overlaying impervious stratum usually of basalt. Wells drilled in the vicinity of Honolulu at an elevation above forty-two feet above the sea have to be pumped. The flowing wells are, as a rule, found at the lower levels. It is of interest to note in this connection that as a rule the shallowest wells are those bored about the ends of radiating lava ridges and that usually their depth increases the nearer they are to the sea-coast. Wells drilled in the middle of valleys are usually deeper than those at either side. All of these facts taken together indicate that the island has been submerged to considerable depth before the subsequent elevation of the raised coral reef on the costal plain about the island, and that the reefs were laid down in submerged valleys that were already deeply eroded before the reefs were formed in them.

In several places, notably at Waianae and Oahu plantations, as well as elsewhere in the group, underground streams have been encountered through horizontal tunnels driven into the mountains, and the underground water supply has been tapped near its head. The tunnel is then extended to the right and left, forming a Y-shaped drain, which brings the water to the surface, far above possible contamination with sea water. Such tunnels are usually driven at altitudes sufficient to admit of distributing the water by gravity over extensive fields well upon the slopes of the mountain. On Maui a daily flow of six million gallons has been secured in this way at an elevation of 2,600 feet. The wonderful Waiahole tunnel on Oahu, built on a modification of this principle. delivers twenty million gallons of water each twenty-four hours.

Economic Products