Hawaiian

Antiquities (Mo`ōlelo Hawai`i)

By David Malo,

Honolulu Hawaiian Gazette Co., Ltd.

|

CHAPTER 15

The Fishes

There are many distinct species of fish in Hawaii. All products of the ocean, whether they move or do not move, are called fish (i'a).1 There are also fish in the inland waters.

The mosses in fresh and salt water are classed with the fish (as regards food). There are many varieties of moss, which are named from their peculiarities, from color, red or black, or from their flavor. The o-o-pu (a small eel-like fish), and the shrimp (opae) are the fish of fresh water.

The fish from shoal and from deep water differ from each other. Some fish are provided with feet, some are beset with sharp bones and spines. Some fish crawl slowly along, clinging to the rocks, while others swim freely about, of which there are many different kinds, some small, some peaked (o-e-o-e; this is also the name of a fish); some flattened, some very flat, some long, some white, some red, many different species in the ocean.

The following fish have feet with prongs: the hihiwai, elepi (a four-footed sea-animal), ele-mihi2 the kukuma (a whitish crab), the kumimi (a poisonous crab), the papa, the pa-pai (a wholesome crab), papai-lanai, the lobster or ula, the alo, the popoki, the ounauna, and the shrimp or opae. These are all good food save the kumimi. That is poisonous and is not eaten.

I will now mention some fish that are beset with spines: the ina, hawae, and wana3 the ha-uke-uke, and the hakue. These fish are all fit to be eaten; their flesh is within their shell. The kokala, oopu-hue and keke are also fish that are covered with spines; they move swiftly through the water and are eaten as food. Death is sometimes caused by eating the oopu-hue.4

The following fish are covered with heavy shells: the pipipi (one of the Nerita, which is excellent eating. TRANSLATOR), the alea-alea, the aoa, the kuanaka, the pupu (a generic name for all shells at the present time), the kuoho, the pu-hookani or conch, the pupu-awa, the olepe (a bivalve), the ole, the oaoaka, the nahana-wele, the uli, the pi-pi, the maha-moe, the opihi, the cowry or leho, the pana-pana-puhi, the pupu-loloa. This is of course not the whole list of what are called fish.

The following are fish that move slowly: the naka, the ku-alakai, the ku-nou-nou, the kona-lelewa, the loli or beche de mer, the mai-hole. the kua-naka, the mini-ole, the lepe-lepe-ohina. These are not fish of fine quality, though they are eaten.

The following small-fry are seen along shore they are swift of motion: the young (pua or flowers) of the mullet or anae (when of medium size it is called ama-ama), of the awa, aholehole, hinana, nehu, iao, piha, opuu-puu ohua-palemo, paoa, oluhe-luhe, ohune, moi-lii, and the akeke. All of these fish are used as food. Doubtless I have omitted the mention of some.

The following fish have bodies with eminences or sharp protuberances (kino oeoe): the paeaea, paniho-loa, olali, hinalea, aki-lolo, ami, mananalo, awela, maha-wela, hou, hilii, omalemale, o-niho-niho opule, lau-ua, ulae, aoao-wela, upa-palu, uhu-eleele, lao, palao, oama. and the aawa. No doubt I have omitted some of them. These fish are excellent eating.

The following fish have flattened bodies: the aloi-loi, ku-pipi, ao-ao-nui, mai-i-i, kole, manini, mamamo, mao-mao, lau-hau,5 laui-pala, mai-ko, maao, humu-humu, kihi-kihi, kika-kapu, ka-pu-hili, oili-lapa, pa-kii, paa-paa, uwi-wi, umauma-lei, walu; and probably these are not all of them. These fish are good eating.

The following are fish with bodies greatly flattened: the kala, palani, nanue, piha-weu-weu, pa-kukui, and the api.

The following fish have bodies of a silvery color: the ahole (same as the ahole-ahole} , anae (full grown mullet), awa, uoa, o-io, opelu, mo-i, u-lua, ulua-mohai, a-ku, ahi, omaka, kawa-kawa, moku-le-ia, la-i, and the hoana, all of which are good eating.

The following are fish with long bodies: the ku-pou-pou, aha, nunu, a'u-a'u, wela, wolu, ono, aulepe, ha-uli-uli; these fish are used as food.

The following fish have bodies of a red color: the a-ala-ihi, u-u, moano, weke (of a pink, salmon and fawn color, a fine fish), a-we-o-we-o,6 ku-mu, pa-ko-le-ko-le, uhu-ula, pa-ou-ou, o-pa-ka-pa-ka, ula-ula, ko-a-e, pihu-weu-weu, o-ka-le-ka-le, muku-muku-waha-nui. These fish are all wholesome food; though probably my list is not complete.

The following fish are furnished with rays or arms (awe-awe); the octopus (he-e), and the mu-he-e (squid?) which are eaten; also the he-e-ma-ko-ko which is bitter.

The following sea-animals have a great resemblance to each other: the sea-turtle or honu, from whose shell is made an instrument useful in scraping olona bark, also in making hair comps in modern times; the e-a, a species of sea-turtle, whose shell was used in making fish-hooks. The honu is excellent eating, but the flesh of the ea is poisonous.

The mano or shark has one peculiarity, he is a man-eater. His skin is used in making drums for the worship of idols, also for the hula and the ka-eke-eke drum. The ka-ha-la and the mahi-mahi are quite unlike other fishes. Their flesh is excellent eating.

The following are fish that breathe on the surface of the ocean: the porpoise or na-ia, nuao, pa-hu, and the whale (ko-hola). The kohola or whale was formerly called the pa-lao-a.7 These fish, cast ashore by the sea, were held to be the property of the king. Both the honu and the ea come to the surface to breathe.

The following fish are provided with (long fins like) wings: the lolo-au ma-lola (the flying-fish), the puhu-kii, lupe, hihi-manu, haha-lua, and the hai-lepo. These fishes are all used as food, but they are not of the finest flavor. No doubt many fish have failed of mention.

CHAPTER 16

The Tapas, Malos, Paus And Mats Of The Hawaiians

Tapa was the fabric that formed the clothing of the Hawaiians. It was made from the bark of certain plants, wauke, mamake, maaloa, and poulu, the skin of young bread-fruit shoots.1 Wauke (Broussonetia papyrifera) was extensively cultivated and the preparation and manufacture of it was as follows: It was the man's work to cut down the branches, after which the women peeled off (uhole) the bark and, having removed the cortex, put the inner bark to soak until it had become soft.

After this it was beaten on the log (kua) with a club called i-e (or i-e kuku. The round club, hohoa, was generally used in the early stage of preparation) until it was flattened out. This was continued for four days, or much longer sometimes, and when the sheet (being kept wet all the time) had been worked until it was broad and thin, it was spread out and often turned, and when dry this was the fabric used as blankets, loin-skirts (pa-u) for the women, and, when made into narrower pieces, as loin-cloths (malos) for the men.2

The mamake (Pipturus albidus) was another of the plants whose bark was made into tapa and used as blankets, malos and pa-us. This was a tree that grew wild in the woods. It was collected by the women who stripped off the bark and steamed it in the oven with pala-a, (a fern that yielded a dark-red coloring matter). If not steamed and stained with pala-a the tapa made from it was called kapa-kele-wai.

Like wauke, it was first soaked until pulpy, when it was beaten on the tapa-log with a club until it had been drawn out thin this might require three or four days after which it was spread out to dry in the sun, and was then used as sheets or blankets, clothing, malos, pans. The mamake made a very durable tapa and could be worn a long time.

The bark of the maaloa and po-ulu, the bark of tender bread-fruit shoots were also beaten into tapa. The method of manufacture was the same as that of wauke and mamake. There were many varieties of tapa, sheets, blankets, robes, malos, pa-us, etc., which the women decorated in different patterns with black, red, green, yellow and other colors.

If, after being stained with the juice of kukui-root, called hili, it was colored with an earth, the tapa was called pu-lo'u; another name for it was o-u-holo-wai.

If the tapa was colored with ma'o (Gossypiuui tomentosum) it was called ma'o-ma'o, green. If stained with the hoolei, (Ochrosia sandwicensis) it took on a yellow color. If unstained the tapa was white. If red cloth was mixed with it in the beating, the tapa was called pa'i-ula, or red-print.3

There was a great variety of names derived from the colors (and patterns) stamped upon them by the women.

The loin-skirts (pau) of the women were colored in many different ways. If stained with turmeric, the pan was called kama-lena, if with cocoanut, it was called hala-kea4 Most of the names applied to the different varieties of pan were derived from the manner in which the women stained (and printed) them.5

In the same way most of the names applied to varieties of the malo were likewise derived from the manner of staining (and printing) them. If stained with the noni (Morinda citrifolia) it was a kua-ula, a red-back, or a pu-kohu-kohu or a pua-kai, seaflower. A pau dyed with turmeric was soft, while some other kinds of pau were stiff. The names applied to pans were as diverse as the patterns imprinted on them; and the same was the case with the malo, of which one pattern was called puali and another kupeke.

These were the fabrics which the ancient Hawaiians used for their comfort, and in robing themselves withal, as loin-girdles for the men, and as loin-skirts for the wromen.

They braided mats6 from the leaves of a tree called the hala (pandanus). The women beat down the leaves with sticks, wilted them over the fire, and then dried them in the sun. After the young leaves (muo) had been separated from the old ones (laele) the leaves were made up into rolls.

This done (and the leaves having been split up into strips of the requisite width) they were plaited into mats. The young leaves (mu-o)7 made the best mats, and from them were made the sails for the canoes. Mats were also made from the makaloa, a fine rush, which were sometimes decorated with patterns inwrought (pawehe). A mat of superior softness and fineness was made from the naku, or tule.

These things were articles of the greatest utility, being used to cover the floor, as clothing, and as robes. This work was done by the women, and was a source of considerable profit; so that the women who engaged in it were held to be well off, and were praised for their skill. Such arts as these were useful to the ancient Hawaiians and brought them wealth.

From the time of Kamehameha I down to the present reign of Kamehameha III we have been supplied with cloth imported from foreign lands. These new stuffs we call lole (to change). It has many names according to the pattern.

CHAPTER 17

The Stone Ax And The New Ax

The ax of the Hawaiians was of stone. The art of making it was handed down from remote ages. Ax-makers were a greatly esteemed class in Hawaii nei. Through their craft was obtained the means of felling trees and of cutting and hewing all kinds of limber used in every sort of wood-work. The manner of making an ax was as follows:

The ax-makers (poe ka-ko'i) prospected through the mountains and other places in search of hard stones suitable for ax-making, carrying with them certain other pieces of hard stone, some of them angular and some of them round in shape, called haku ka-koi, to be used in chipping and forming the axes.

After splitting the rock and obtaining a long fragment, they placed it in a liquor made from vegetable juices (wai-laau)1 which was supposed to make it softer, and this accomplished, they chipped it above and below, giving it the rude shape of an ax.

The lower part of the ax which is rounded (e polipoli ana) is termed the pipi; the upper part which forms an angle with it is termed the hau-hana. When the shape of the thing has been blocked out, they apply it to. the grind-stone, hoana,2 sprinkled with sand and water. The upper side and the lower side were ground down and then the edge was sharpened. The joiner's ax (koi kapili) had a handle of hau, or some other wood.

The next thing was to braid some string, to serve as a lashing, to fit the handle to the ax, to wrap a protecting cloth (pale) about it (in order to save the lashing from being cut by the chips), and lastly, to bind the ax firmly to the handle, which done, the ax was finished. The ax now became an object of barter with this one and that one, and thus came into the hands of the canoemaker.

The shell called o-le3 served as an ax for some purposes, also a hard wood called ala-hee. There were a few axes made from (scraps of) iron, but the amount of iron in their possession was small. It was with such tools as these that the Hawaiians hewed out their canoes, house-timber and did a great variety of wood-work. The ax was by the ancients reckoned an article of great value. How pitiful!

Now come new kinds of axes from the lands of the white man. But iron had reached Hawaii before the arrival of the foreigner, a jetsam iron which the chiefs declared sacred to the gods. (He hao pae, ua hai na 'lii i na kua kii.)

There was, however, very little iron here in those old times. But from the days of Kamehameha I down to those of Kamehameha III, iron has been abundant in this country.

Iron is plentiful now, and so are all kinds of iron tools, including the kitchen-ax, the hatchet, the adze, broad-ax, chisel, etc.

These are the new tools which have been imported. The stone ax (koi-pohaku) is laid aside.

CHAPTER 18

The Alii And The Common People

The physical characteristics of the chiefs and the common people of Hawaii nei were the same; they were all of one race; alike in features and physique.1 Commoners and alii were all descended from the same ancestors, Wakea and Papa. The whole people were derived from that couple. There was no difference between king and plebeian as to origin. It must have been after the time of Wakea that the separation of the chiefs from the people took place.

It is probable that because it was impossible for all the people to act in concert in the government, in settling the difficulties, lifting the burdens, and disentangling the embarrassments of the people from one end of the land to the other that one was made king, with sole authority to conduct the government and to do all its business. This most likely was the reason why certain ones were selected to be chiefs. But we are not informed who was the first one chosen to be king; that is only a matter of conjecture.

The king was appointed (hoonoho ia mai; set up would be a more literal translation) that he might help the oppressed who appealed to him, that he might succor those in the right and punish severely those in the wrong. The king was over all the people; he was the supreme executive, so long, however, as he did right.

His executive duties in the government were to gather the people together in time of war, to decide all important questions of state, and questions touching the life and death of the common people as well as of the chiefs and. his comrades in arms. It was his to look after the soldiery. To him belonged the property derived from the yearly taxes, and he was the one who had the power to dispossess commoners and chiefs of their lands.

It was his to assess the taxes both on commoner and on chiefs and to impose penalties in case the land-tax was not paid. He had the power to appropriate, reap or seize at pleasure, the goods of any man, to cut off the ear of another man's pig, (thus making it his own). It was his duty to consecrate the temples, to oversee the performance of religious rites in the temples of human sacrifice, (na heiau poo-kanaka, oia hoi na luakini) that is, in the luakini, to preside over the celebration of the Makahiki festival, and such other ceremonies as he might be pleased to appoint.

From these things will be apparent the supremacy of the king over the people and chiefs. The soldiery were a factor that added to the king's pre-eminence. It was the policy of the government to place the chiefs who were destined to rule, while they were still young, with wise persons, that they might be instructed by skilled teachers in the principles of government, be taught the art of war, and be made to acquire personal skill and bravery.

The young man had first to be subject to another chief, that he might be disciplined and have experience of poverty, hunger, want and hardship, and by reflecting on these things learn to care for the people with gentleness and patience, with a feeling of sympathy for the common people, and at the same time to pay due respect to the ceremonies of religion and the worship of the gods, to live temperately, not violating virgins (aole lima koko kohe),2 conducting the government kindly to all.

This is the way for a king to prolong his reign and cause his dynasty to be perpetuated, so that his government shall not be overthrown. Kings that behave themselves and govern with honesty, their annals and genealogies will be preserved and treasured by the thoughtful and the good.

Special care was taken in regard to chiefs of high rank to secure from them noble offspring, by not allowing them to form a first union with a woman of lower rank than themselves, and especially not to have them form a first union with a common or plebeian woman (wahine noa).

To this end diligent search was first made by the genealogists into the pedigree of the woman, if it concerned a high born prince, or into the pedigree of the man, if it concerned a princess of high birth, to find a partner of unimpeachable pedigree; and only when such was found and the parentage and lines of ancestry clearly established, was the young man (or young woman) allowed to form his first union, in order that the offspring might be a great chief.

When it was clearly made out that there was a close connection, or identity, of ancestry between the two parties, that was the woman with whom the prince was first to pair. If the union was fruitful, the child would be considered a high chief, but not of the highest rank or tabu. His would be a kapu a noho, that is the people and chiefs of rank inferior to his must sit in his presence.

A suitable partner for a chief of the highest rank was his own sister, begotten by the same father and mother as himself. Such a pairing was called a pi'o (a bow, a loop, a thing bent on itself); and if the union bore fruit, the child would be a chief of the highest rank, a ni nau pi'o, so sacred that all who came into his presence must prostrate themselves. He was called divine, akua. Such an alii would not go abroad by day but only at night, because if he went abroad in open day (when people were about their usual avocations), every one had to fall to the ground in an attitude of worship,

Another suitable partner for a great chief was his half sister, born, it might be of the same mother, but of a different father, or of the same father but of a different mother. Such a union was called a naha. The child would be a great chief, niau-pio; but it would have only the kapu-a-noho (sitting tabu).

If such unions as these could not be obtained for a great chief, he would then be paired with the daughter of an elder or younger brother, or of a sister. Such a union was called a hoi (return). The child would be called a niau-pio, and be possessed of the kapu-moe.

This was the practice of the highest chiefs that their first born might be chiefs of the highest rank, fit to succeed to the throne.

It was for this reason that the genealogies of the kings were always preserved by their descendants, that the ancestral lines of the great chiefs might not be forgotten; so that all the people might see clearly that the ancestors on the mother's side were all great chiefs, with no small names among them; also that the father's line was pure and direct. Thus the chief became peerless, without blemish, sacred (kuhau-lua, ila-ole, hemolele).

In consequence of this rule of practice, it was not considered a thing to be tolerated that other chiefs should associate on familiar terms with a high chief, or that one's claim of relationship with him should be recognized until the ancestral lines of the claimant had been found to be of equal strength (manoanoa, thickness) with those of the chief; only then was it proper for them to call the chief a maka-maka (friend, or intimate maka means eye).

Afterwards, when the couple had begotten children of their own, if the man wished to take another woman or the woman another man even though this second partner were not of such choice blood as the first, it was permitted them to do so. And if children were thus begotten they were called kaikaina, younger brothers or sisters of the great chief, and would become the backbone (iwi-kua-moo) , executive officers (ila-muku) of the chief, the ministers (kuhina) of his government.

The practice with certain chiefs was as follows: if the mother was a high chief, but the father not a chief, the child would rank somewhat high as a chief and would be called an alii papa (a chief with a pedigree) on account of the mother's high rank.

If the father was a high chief, and the mother of low rank, but a chiefess, the child would be called a kau-kau-alii.3 In case the father was a chief and the mother of no rank whatever, the child would be called a kulu, a drop; another name was ua-iki, a slight shower; still another name was kukae-popolo. (I will not translate this). The purport of these appellatives is that chiefish rank is not clearly established.

If a woman who was a kaukau-alii, living with her own husband, should have a child by him and should then give it away in adoption to another man, who was a chief, the child would be an alii-poo-lua, a two-headed chief.

Women very often gave away their children to men with whom they had illicit relations.4 It was a common thing for a chief to have children by this and that woman with whom he had enjoyed secret amours. Some of these children were recognized and some were not recognized.

One of these illegitimates would be informed of the fact of his chiefish ancestry, though it might not be generally known to the public. The child in such case, was called an alii kuauhau (chief with an ancestry), from the fact that he knew his pedigree and could thus prove himself an alii.

Another one would merely know that he had alii blood in his veins, and on that account perhaps he would not suffer his clothing to be put on the same frame or shelf as that of another person. Such an one was styled a clothes-rack-chief (alii-kau-holo-papa) , because it was in his solicitude about his clothes-rack that he distinguished himself as an alii.

If a man through having become a favorite (punahele) or an intimate (aikane) of an alii, afterwards married a woman of alii rank, his child by her would be called a kau-kau-alii,5 or an alii maoli (real alii).

A man who was enriched by a chief with a gift of land or other property was called an alii lalo-lalo, a low down chief. Persons were sometimes called alii by reason of their skill or strength. Such ones were alii only by brevet title.

The great chiefs were entirely exclusive, being hedged about with many tabus, and a large number of people were slain for breaking, or infringing upon, these tabus. The tabus that hedged about an alii were exceedingly strict and severe. Tradition does not inform us what king established these tabus. In my opinion the establishment of the tabu-system is not of very ancient date, but comparatively modern in origin.

If the shadow of a man fell upon the house of a tabu-chief, that man must be put to death, and so with any one whose shadow fell upon the back of the chief, or upon his robe or malo, or upon anything that belonged to the chief. If any one passed through the private doorway of a tabu-chief, or climbed over the stockade about his residence, he was put to death.6

If a man entered the alii's house without changing his wet malo, or with his head smeared with mud, he was put to death. Even if there were no fence surrounding the alii's residence, only a mark, or faint scratch in the ground hidden by the grass, and a man were to overstep this line unwittingly, not seeing it, he would be put to death.

When a tabu-chief ate, the people in his presence must kneel, and if any one raised his knee from the ground, he was put to death. If any man put forth in a kio-loa7 canoe at the same time as the tabu-chief, the penalty was death.

If any one girded himself with the king's malo, or put on the king's robe, he was put to death. There were many other tabus, some of them relating to the man himself and some to the king, for violating which any one would be put to death.

A chief who had the kapu-moe, as a rule, went abroad only at night; but if he travelled in daytime a man went before him with a flag calling out "kapu! moe!" whereupon all the people prostrated themselves. When the containers holding the water for his bath, or when his clothing, his malo, his food, or anything that belonged to him, was carried along, every one must prostrate himself; and if any remained standing, he was put to death. Kiwalao was one of those who had this kapu-moe.

An alii who had the kapu-wohi8 and his kahili-bearer, who accompanied him, did not prostrate himself when the alii with the kapu-wohi came along; he just kept on his way without removing his lei or his garment.

Likewise with the chief who possessed the kapu-a-noho, when his food-calabashes, bathing water, clothing, malo, or anything that belonged to him, was carried along the road, the person who at such a time remained standing was put to death in accordance with the law of the tabu relative to the chiefs.

The punishment inflicted on those who violated the tabu of the chiefs was to be burned with fire until their bodies were reduced to ashes, or to be strangled, or stoned to death. Thus it was that the tabus of the chiefs oppressed the whole people.

The edicts of the king had power over life and death. If the king had a mind to put some one to death, it might be a chief or a commoner, he uttered the word and death it was.

But if the king chose to utter the word of life, the man's life was spared.

The king, however, had no laws regulating property, or land, regarding the payment or collection of debts, regulating affairs and transactions among the common people, not to mention a great many other things.

Every thing went according to the will or whim of the king, whether it concerned land, or people, or anything else not according to law.

All the chiefs under the king, including the konohikis who managed their lands for them, regulated land-matters and everything else according to their own notions.

There was no judge, nor any court of justice, to sit in judgment on wrong-doers of any sort. Retaliation with violence or murder was the rule in ancient times.

To run away and hide one's self was the only resource for an offender in those days, not a trial in a court of justice as at the present time.

If a man's wife was abducted from him he would go to the king with a dog as a gift, appealing to him to cause the return of his wife, or the woman for the return of her husband, but the return of the wife, or of the husband, if brought about, was caused by the gift of the dog, not in pursuance of any law. If any one had suffered from a great robbery, or had a large debt owing him, it was only by the good will of the debtor, not by the operation of any law regulating such matters that he could recover or obtain justice. Men and chiefs acted strangely in those days.

There was a great difference between chiefs. Some were given to robbery, spoliation, murder, extortion, ravishing. There were few kings who conducted themselves properly as Kamehameha I did. He looked well after the peace of the land.

On account of the rascality (kolohe) of some of the chiefs to the common people, warlike contests frequently broke out between certain chiefs and the people, and many of the former were killed in battle by the commoners. The people made war against bad kings in old times.

The amount of property which the chiefs obtained from the people was very great. Some of it was given in the shape of taxes, some was the fruit of robbery and extortion.

Now the people in the out-districts (kua-aina) were as a rule industrious, while those about court or who lived with the chiefs were indolent, merely living on the income of the land. Some of the chiefs carried themselves haughtily and arrogantly, being supported by contributions from others without labor of their own. As was the chief, so were his retainers (kanaka).

On this account the number of retainers, servants and hangers-on about the courts and residences of the kings and high chiefs was very great. The court of a king offered great attractions to the lazy and shiftless.

These people about court were called pu-ali9 or ai-alo (those who eat in the presence), besides which there were many other names given them. One whom the alii took as an intimate was called ai-kane. An adopted child was called keiki hookama.

The person who brought up an alii and was his guardian was called a kahu; he who managed the distribution of his properly was called a puu-ku. The house where the property of the alii was stored was called a hale pa-paa (house with strong fence). The keeper of the king's apparel (master of the king's robes), or the place where they were stored, was called hale opeope, the folding house.

The steward who had charge of the king's food was called an 'a- i-puu-puu, calloused-neck. He who presided over the king's pot de chambre was called a lomi-lomi, i.e., a masseur. He who watched over the king during sleep was called kiai-poo, keeper of the head. The keeper of the king's idol was called kahu-akua.

The priest who conducted the religious ceremonies in the king's heiau was a kahuna pule. He who selected the site for building a heiau and designed the plan of it was called a kuhi-kuhi puu-one.10 He who observed and interpreted the auguries of the heavens was called a kilo-lani. A person skilled in strategy and war was called a kaa-kaua. A counselor, skilled in statecraft, was called a kalai-moku (kalai, to hew; moku, island.) Those who farmed the lands of the king or chiefs were kono-hiki.

The man who had no land was called a kaa-owe.11 The temporary hanger-on was called a kua-lana (lana, to float. After hanging about the alii's residence for a time, he shifted to some other alii. TRANSLATOR); another name for such a vagrant was kuewa (a genuine tramp, who wheedled his way from place to place). The servants who handled the fly-brushes kahili, about the king's sleeping place were called haa-kue; another name for them was kua-lana-puhi; or they were called olu-eke-loa-hoo-kaa-moena.12

Beggars were termed auhau-puka13 or noi (a vociferous beggar), or makilo (a silent beggar), or apiki.14

One who was born at the residence of the king or of a chief was termed a kanaka no-hii-alo, or if a chief, alii no-hii-alo (noho i ke alo). A chief who cared for the people was said to be a chief of aau-loa15 or of mahu-kai-loa. A man who stuck to the service of a chief through thick and thin and did not desert him in time of war, was called a kanaka no kahi kaua, a man for the battle-field. This epithet was applied also to chiefs who acted in the same way.

People who were clever in speech and at the same time skillful workmen were said to be noeau or noian. There are many terms applicable to the court, expressive of relations between king and chiefs and people, which will necessarily escape mention.

As to why in ancient times a certain class of people were ennobled and made into aliis, and another class into subjects (kanaka), why a separation was made between chiefs and commoners, has never been explained.

Perhaps in the earliest times all the people were alii16 and it was only after the lapse of several generations that a division was made into commoners and chiefs; the reason for this division being that men in the pursuit of their own gratification and pleasure wandered off in one direction and another until they were lost sight of and forgotten.

Perhaps this theory will in part account for it: a handsome, but worthless, chief takes up with a woman of the same sort, and, their relatives having cast them out in disgust, they retire to some out of the way place; and their children, born in the back-woods amid rude surroundings, are forgotten.17

Another possible explanation is that on account of lawlessness, rascality, dishonorable conduct, theft, impiousness and all sorts of criminal actions that one had committed, his fellow chiefs banished him, and after long residence in some out of the way place, all recollection of him and his pedigree was lost.18

Another reason no doubt was that certain ones leading a vagabond life roamed from place to place until their ancestral genealogies came to be despised, (wahawaha ia) and were finally lost by those whose business it was to preserve them. This cause no doubt helped the split into chiefs and commoners.

The commoners were the most numerous class of people in the nation, and were known as the ma-ka-aina-na; another name by which they were called was hu (Hu, to swell, multiply, increase like yeast.) The people who lived on the windward, that was the back, or koolau side of any island, were called kua-aina or back-country folks, a term of depreciation, however.

The condition of the common people was that of subjection to the chiefs, compelled to do their heavy tasks, burdened and oppressed, some even to death. The life of the people was one of patient endurance, of yielding to the chiefs to purchase their favor. The plain man (kanaka) must not complain.

If the people were slack in doing the chief's work they were expelled from their lands, or even put to death. For such reasons as this and because of the oppressive exactions made upon them, the people held the chiefs in great dread and looked upon them as gods.

Only a small portion of the kings and chiefs ruled with kindness; the large majority simply lorded it over the people.

It was from the common people, however, that the chiefs received their food and their apparel for men and women, also their houses and many other things. When the chiefs went forth to war some of the commoners also went out to fight on the same side with them.

The makaainana were the fixed residents of the land; the chiefs were the ones who moved about from place to place. It was the makaainanas also who did all the work on the land; yet. all they produced from the soil belonged to the chiefs; and the power to expel a man from the land and rob him of his possessions lay with the chief.

There were many names descriptive of the makaainanas. Those who were born in the back districts were called kanaka no-hii-kua (noho-i-kua) , people of the back. The man who lived with the chief and did not desert him when war came, was called a kanaka no lua-kaua, a man for the pit of battle.

The people were divided into farmers, fishermen, house-builders, canoe-makers (kalai-waa), etc. They were called by many different appellations according to the trades they followed.

The (country) people generally lived in a state of chronic fear and apprehension of the chiefs; those of them, however, who lived immediately with the chief were (to an extent) relieved of this apprehension.19

After sunset the candles of kukui-nuts were lighted and the chief sat at meat. The people who came in at that time were called the people of lani-ka-e,20 Those who came in when the midnight lamp was burning (ma ke kui au-moe) were called the people of pohokano. This lamp was merely to talk by, there was no eating being done at that time.

The people who sat up with the chief until day-break (to carry-on, tell stories, gossip, or perhaps play some game, like konane. TRANSLATOR) ) were called ma-ko-u21 because that was the name of the flambeau generally kept burning at that hour.

There were three designations applied to the kalai-moku, or counselors of state. The kalaimoku who had served under but one king was called lani-ka'e. He who had served under two kings was called a pohokano, and if one had served three kings he was termed a ma-ko'u. This last class were regarded as being most profoundly skilled in state-craft, from the fact that they had had experience with many kings and knew wherein one king had failed and wherein another had succeeded.

It was in this way that these statesmen had learned by experience that one king by pursuing a certain policy had met with disaster, and how another king, through following a different policy had been successful. The best course for the king would have been to submit to the will of the people.

CHAPTER 19

Life In The Out-Districts And At The King's Residence

The manner of life in the out-districts was not the same as that about the residence of the chief. In the former the people were cowed in spirit, the prey of alarm and apprehension, in dread of the chiefs man.

They were comfortably off, however, well supplied with everything. Vegetable and animal food, tapa for coverings, girdles and loin-cloths and other comforts were in abundance.

To eat abundantly until one was sated and then to sleep and take one's comfort, that was the rule of the country. Sometimes, however, they did suffer hunger and feel the pinch of want The thrifty, however, felt its touch but lightly; as a rule they were supplied with all the comforts of life.

The country people were well off for domestic animals. It was principally in the country that pigs, dogs and fowls were raised, and thence came the supply for the king and chiefs.

The number of articles which the country (kua-aina) furnished the establishments of the kings and chiefs was very great. The country people were strongly attached to their own homelands, the full calabash,1 the roasted potatoes, the warm food, to live in the midst of abundance. Their hearts went out to the land of their birth.

It was a life of weariness, however; they were compelled at frequent intervals to go here and there, to do this and that work for the lord of the land, constantly burdened with one exaction or another.

The country people2 were humble and abject; those about the chiefs overbearing, loud-mouthed, contentious.

The wives of the country people were sometimes appropriated by the men about court, even the men were sometimes separated from their country wives by the women of the court, and this violence was endured with little or no resistance, because these people feared that the king might take sides against them. In such ways as these the people of the kua-aina were heavily oppressed by the people who lived about court.3

Some of the country people were very industrious and engaged in farming or fishing, while others were lazy and shiftless, without occupation. A few were clever, but the great majority were inefficient. There was a deal of blank stupidity among them.

These country people were much given to gathering together for some profitless occupation or pastime for talk's sake (hoolua nui), playing the braggadocio (hoo-pehu-pehu), when there was nothing to back up their boasts (oheke wale). The games played by the country people were rather different from those in vogue at court or at the chief's residence. Some people preferred the country to the court.

Many people, however, left the country and by preference came to live near the chiefs. These country people were often oppressive toward each other, but there was a difference between one country district and another.

The bulk of the supplies of food and of goods for chiefs and people was produced in the country districts. These people were active and alert in the interests of the chiefs.

The brunt of the hard work, whether it was building a temple, hauling a canoe-log out of the mountains, thatching a house, building a stone-wall, or whatever hard work it might be, fell chiefly upon the kua-ainas.

Life about court was very different from that in the country. At court the people were indolent and slack, given to making excuses (making a pretense of) doing some work, but never working hard.

People would stay with one chief awhile and then move on to another (pakaulei). There was no thrift; people were often hungry and they would go without their regular food for several days. At times there was great distress and want, followed by a period of plenty, if a supply of food was brought in from the country.

When poi and fish were plentiful at court the people ate with prodigality, but when food became scarce one would satisfy his hunger only at long intervals (maona kalawalawa. Kawalawala is the received orthography). At times also tapa-cloth for coverings and girdles, all of which came from the country, were in abundance at court.

At other times people about court, on account of the scarcity of cloth, were compelled to hide their nakedness with rnalos improvised from the narrow strips of tapa (hipuupuu)4 that came tied about the bundles of tapa-cloth. A man would sometimes be compelled to make the kihei which was his garment during the day, serve him for a blanket by night, or sometimes a man would sleep under the same covering with another man. Some of the people about court were well furnished with all these things, but they were such ones as the alii had supplied.

Of the people about court there were few who lived in marriage. The number of those who had no legitimate relations with women was greatly in the majority. Sodomy5 and other unnatural vices6 in which men were the correspondents, fornication and hired prostitution7 were practiced about court.

Some of the sports and games indulged in by the people about court were peculiar to them, and those who lived there became fascinated by the life. The crowd of people who lived about court was a medley of the clever and the stupid, a few industrious workers in a multitude of drones.

Among those about court there were those who were expert in all soldierly accomplishments, and the arts of combat were very much taught. Many took lessons in spear-throwing (lono-maka-ihe8,) spear-thrusting, pole-vaulting (ku-pololu9) , single-stick (kaka-laau10), rough-and-tumble wrestling (kaala11), and in boxing (kui-alua).12 All of these arts were greatly practiced about court.

In the cool of the afternoon sham fights were frequently indulged in; the party of one chief being pitted against the party of another chief, the chiefs themselves taking part.

These engagements were only sham fights and being merely for sport were conducted with blunted spears, (kaua kio) or if sharp spears were used it was termed kaua pahu-kala. These exercises were useful in training the men for war.

In spite of all precautions many of the people, even of the chiefs, were killed in these mock battles. These contests were practiced in every period in the different islands to show the chiefs beforehand who among the people were warriors, so that these might be trained and brought up as soldiers, able to defend the country at such time as the enemy made war upon it. Some of the soldiers, however, were country people.

One of the games practiced among the people about court was called honuhonu13. Another sport was lou-lou14. Another sport was uma15. Hakoko, wrestling; kahau16, lua17. The people who attended the chiefs at court were more polite in their manners than the country people, and they looked disdainfully upon country ways. When a chief was given a land to manage and retired into the country to live, he attempted to keep up the same style as at court.

The people about court were not timid nor easily abashed; they were not rough and muscular in physique, but they were bold and impudent in speech. Some of the country people were quite up to them, however, and could swagger and boast as if they had been brought up at court.

There was hardly anybody about court who did not practice robbery, and who was not a thief, embezzler, extortionist and a shameless beggar. Nearly every one did these things.

As to the women there was also a great difference between them. Those who lived in the country were a hard-working set, whereas those about court were indolent.

The women assisted their husbands; they went with them into the mountains to collect and prepare the bark of the wauke, mamake, maaloa and bread-fruit, and the flesh of the fern-shoot (pala-holo18) to be made into tapa. She beat out these fibres into tapa and stamped the fabrics for paus and malos, that she and her husband might have the means with which to barter for the supply of their wants.

The country women nursed their children with the milk of their own breasts, and when they went to any work they took them along with them. But this was not always the case; for if a woman had many relations, one of them, perhaps her mother (or aunt), would hold the child. Also if her husband was rich she would not tend the child herself; it would be done for her by some one hired for the purpose, or by a friend.

The indolent women in the country were very eager to have a husband who was well off, that they might live without work. Some women offered worship and prayers to the idol gods that they might obtain a wealthy man, or an alii for a husband. In the same way, if they had a son, they prayed to the idols that he might obtain a rich woman or a woman of rank for his wife, so that they might live without work.

It was not the nature of the women about court to beat tapa or to print it for paus and malos. They only made such articles as the alii specially desired them to make.

All the articles for the use of the people about court, the robes, malos, paus, and other necessaries (mea e pono ai) were what the chiefs received from the people of the country.

One of the chief employments of the women about court was to compose meles in honor of the alii19 which they recited by night as well as by day.

CHAPTER 20

Concerning Kauwa

There was a class of people in the Hawaiian Islands who were called kauwa, slaves. This word kauwa had several meanings. It was applied to those who were kauwa by birth as well as those who were alii by birth.

Kauwa was a term of degradation and -great reproach. But some were kauwa only in name; because the younger brother has always been spoken of as the kauwa of the elder brother. But he was not his kauwa in fact. It was only a way of indicating that the younger was subject to the older brother.

So it was with all younger brothers or younger sisters in relation to their elder brothers or elder sisters, whether chiefs or commoners.

Those who had charge of the chief's goods or who looked after his food were called kauwa. Their real name was 'a-'i-pu'u-pu'u and they were also called kauwa; but they were kauwa only in name, they were not really slaves.

There were people who made themselves kauwa, those who went before the king, or chief, for instance, and to make a show of humbling themselves before him said, "We are your kauwa." But that was only a form of speech.

Again people who lived with the rich were sometimes spoken of as their kauwa. But they were not really kauwa; that term was applied to them on account of their inferior position.

Mischievous, lawless people (poe kolohe) were among those who were sometimes called kauwa, and it was the same with the poor. But they were not the real kauwa; it was only an epithet applied to them.

When one person quarreled with another he would sometimes revile him and call him a kauwa; but that did not make him a real kauwa, it was only an epithet for the day of his wrath, anger and reviling.

The marshals or constables (ilamuku) of the king were spoken of as his kauwa, but they were not really kauwa. There were then many classes of people called or spoken of as kauwa, but they were kauwa only in name, to indicate their inferior rank; they were not really and in fact kauwa. The people who were really and in fact kauwa were those who were born to that condition and whose ancestors were such before them. The ancestral line of the people (properly to be) called kauwa from Papa down is as follows:

The name kauwa was an appellation very much feared and dreaded. If a contention broke out between the chiefs and the people and there was a fracas, pelting with stones and clubbing with sticks, but they did not exchange reviling epithets and call each other kauwa, the affair would not be regarded as much of a quarrel.

But if a man or a chief contended with his fellow or with any one, and they abused each other roundly, calling one another kauwa; that was a quarrel worth talking about, not to be forgotten for generations.

The epithet kauwa maoli, real slave, was one of great offense. If a man formed an alliance with a woman, or a woman with a man, and it afterwards came out that that woman or that man was a kauwa, that person would be snatched away from the kauwa by his friends or relatives without pity.

If a chief or a chiefess lay with one who was a kauwa, not knowing such to be the fact, and afterwards should learn that the person was a kauwa, the child, if any should be born, would be dashed to death against a rock. Such was the death dealt out to one who was abhorred as a kauwa.

The kauwa class were so greatly dreaded and abhorred that they were not allowed to enter any house but that of their master, because they were spoken of as the aumakua of their master.

Those who were kauwa to their chiefs and kings in the old times continued to be kauwa, and their descendants after them to the latest generations; also the descendants of the kings and chiefs, their masters, retained to the latest generation their position as masters. It was for this reason they were called aumakua, the meaning of which is ancient servant (kauwa kahiko). They were also called akua. i.e., superhuman or godlike (from some superstitious notion regarding their power). Another name applied to them was kauwa lepo, base-born slave (lepo, dirt. "Mud-sill"); or an outcast slave, kauwa haalele loa, which means a most despised thing.

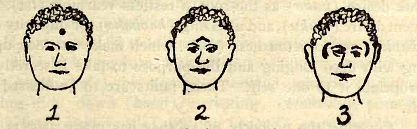

Those kauwa who were tattooed on the forehead were termed kauwa lae-puni, slaves with bound foreheads; or they were called kauwa kikoni, the pricked slave; or kauwa makawela, red-eyed slave. These were most opprobrious epithets.

If a person of another class had a child by one of these au-makuas or kauwas, the term no'u was applied to it, which meant that it also was a kauwa to the same master.

Some people of other classes, and of the alii class as we'll, formed connections with kauwas, either through ignorance or through concupiscence, or because they happened to have met a fine-looking woman or man of the kauwa class. In this way some aliis, as well as others, became entangled (hihia). Children begotten of such a union were termed ula-ula-ili, red skin (from the sun-burn acquired by exposure through neglect and nakedness). Men and women who were kauwa were said to be people from the wild woods (nahelehele) , from the lowest depths no lalo liio loa).

It was for this reason that the rank of the first woman or man with whom a great chief or chiefess was paired, was so carefully considered beforehand by those skilled in genealogies (kuauhau), who knew the standing of the woman or man in question, whether an alii or a kauwa.

For the same reason great chiefs were sometimes paired with their elder sisters (or elder brothers, as the case might be), with some member of their own family, lest by any chance they might unite with a kauwa.

It was for this reason also that the genealogies of the aliis were always carefully preserved, that it might be clear who were free from the taint of kauwa blood, that such only might be paired with those of alii rank.

It was a matter likely to cause the death of a high chief to have it said of him that he was an alii kauwa. In such a case the most expert genealogists would be summoned to search the matter to the bottom. Genealogists were called the wash-basins of the aliis, in which to cleanse them. The kauwa class were regarded as a defilement and a stench.

A female kauwa was an outcast and was not allowed to enter the eating house of a female chief.

CHAPTER 21

Wrong Conduct And Right Conduct (Na Hewa Me Na Pono)

The Ancient Idea of Morality.

There are many kinds of wrong committed by men, if their number were all told; but a single stem gives birth to them all. The thought that proceeds from, the mind is the parent that begets a multitude of sins.1

When the heart proposes to do wrong then doubtless it will commit a sin; and when it purposes to do right, then no doubt, it will do right; because from the heart (naau, bowels) comes good and from the heart also comes evil. But some evils light down of themselves (lele wale mai), and so do some good things.

If the eye sees a thing, but the heart does not covet it, no wrong is done. But if the eye observes and the heart covets a certain thing, a great many thoughts will arise within having inordinate desire (kuko) as the root, a restless yearning (lia), a vehement desire (uluku), and a seizing (hookaha); or duplicity (hoo-maka-uli'i) and covetousness (iini), which make one look upon a thing with deep longing and the purpose to take it secretly and appropriate it to one self. These faults are to be classed with theft.

Coveting the property of another has many aspects to it, a spying upon another, lying in ambush on his trail, plotting, treachery, deceit, trickery with the intent to murder secretly in order to get someone's goods. All of these things come under the head of robbery and are of the nature of murder (pepehi wale) .

If one has determined to enrich himself at another's expense the evil has many shapes. The first thing is covetousness (pakaha), filching, thrusting one's self on the hospitality of one's neighbor (kipa wale), stripping another of his property (hao wale), appropriating his crops (uhuki wale), theft, robbery and other wrong deeds of that nature.

If a man wishes to deal truthfully with another and afterwards finds that things have been misrepresented to him, there are many things involved in that. In the first place there is deceit (hoo-punipuni), lying (waha-he'e), slander (alapahi) , falsehood (palau), the lie jestful (ku-kahe-kahe) t the lie fluent (palolo). the lie unclothed, (kokahe), the lie direct, (pahilau), and many other things of like sort.

If a person seeks to find fault with another there are many ways of doing it, the chief of which is slander (aki, biting), defamation (ahiahi), making false accusations (niania), circulating slanders (holoholo oleo), vilifying (makauli'i) , detraction (kaa-mehai, belittling (kuene), tale-bearing (poupou-noho-ino), ensnaring (hoowalewale), misleading (luahele), treachery (ku-makaia), fault-finding (hoolawehala) , malice (opu-inoino) , scandal-mongering (lawe-olelo-wale) , reviling (paonioni) and a host of other things of the same sort.

If one has evil thoughts against another there are a great many ways in which they may express themselves. The first is anger (huhu), indignation (inaina), sarcasm (a-aka), scolding (keke), fault-finding (nana), sourness (kukona), bitterness (na-hoa), fretfulness (makona) , rudeness (kalaea) , jealousy (hoo-lili) , scowling (hoomakue), harshness hookoikoi), intimidation (hooweliweli) and many other ways.

If a man wished to kill an innocent person there are many ways in which he can do it, first to simply beat him to death (pepehi wale), by stoning (hailuku), whipping (hahau) r knocking him down (kulai), garroting (umiwale), pounding; with his fists (kuku'i wale), smiting (papa'i), wrestling (hako'o-ko'o), stirring up a fight (hookonokono) , and many other similar ways.

These were all sins, clearly understood to be very wrongs but those who did these things were not suitably punished in the old times. If any one killed another, nothing was done about it there was no law. It was a rare thing for any one to be punished as at the present time.2

t should be remarked here that in ancient times indiscriminate sexual relations between unmarried persons (moe o na mea kaawale), fornication, keeping a lover (moe ipo), hired prostitution (moe kookuli), bigamy, polyandry, whoredom (moe hoo-kama-kama), sodomy (moe aikane), and masturbation were not considered wrong, nor were foeticide and idol-worship regarded as evils.

The following things were held to be wrong, hewa, both in men and women: to change husband or wife frequently; (ko-aka); to keep shifting from place to place, to be a glutton or to in men and women: to change husband or wife frequently; gossip (palau-alelo); to be indolent and lazy, to be an improvident vagabond (aea, kuonoono-ole); to be utterly shiftless (lima-liina-piiau); to go about getting food at other people's houses (koalaala-make-hewa) these and other like actions were really wrong, hewa.

The following practices were considered hewa by the landlord, that one should give himself up to the fascinations of sport and squander his property in puhenehene; sliding the stick (pahee); bowling the ulu-maika; racing with the canoe, on the surf-board or on the holua-sled, that one should build a large house, have a woman of great beauty for his wife, sport a fine tapa, or gird one's self with a fine malo.

All of these things were regarded as showing pride, and were considered valid reasons for depriving a man of his lands, because such practices were tantamount to secreting wealth.

If a landlord, or land agent, who farmed the land for an alii (kono-hiki) had to wife a woman who did no work, neither beating out or printing tapa, doing nothing in fact, but merely depending on what her husband produced, such a non-producer was called a polo-hana-ole, and it would be counted a hewa, and a sufficient reason why the man should be turned out of his lands.

Mere complaining and grumbling, with some other misfortunes are evils that come of themselves. There are other ills of the same sort which I have not mentioned.

There was a large number of actions that were considered essentially good (pono maoli) , and the number of persons who did them was very considerable, in spite of which there lighted down upon them the misfortune that when they looked upon the things belonging to another their heart lusted after them. The right course in such a case is to resist the temptation, not to pursue the object of one's desire, to cease thinking about it and touch it not.

To act justly without trespassing or deceiving, not frequenting another's house, not gazing wistfully upon your neighbor's goods nor begging for anything that belongs to him that is the prudent course.

The following actions were considered worthy of approbation; to live thriftily, not to be a vagabond, not to keep changing wives, not to be always shifting from one chief to another, not to run in debt.

It was reckoned a virtue for a man to take a wife, to bring up his children properly, to deal squarely with his neighbors and his landlord, to engage in some industry, such as fanning, fishing, house-building, canoe-making, or to raise swine, dogs and fowls.

It was also deemed virtuous not to indulge in sports, to abstain from such games as puhenehene, pahee, bowling the maika, running races, canoe-racing, surf-riding, racing on the holua-sled, and to abstain from the tug-of-war and all other games of such sort.

The practice of these virtues was a great means of bettering one's self in this life and was of great service.

The farmer and the fisherman acquired many servants and accumulated property by their labors. For this reason the practice of these callings was regarded as most commendable.

The worship of idols was regarded as a virtue by the ancients, because they sincerely believed them to be real gods. The consequence was that people desired their chiefs and kings to be religious (haipule) . The people had a strong conviction that if the king was devout, his government would abide.

Canoe-building was a useful art. The canoe was of service in enabling one to sail to other islands and carry on war against them, and the canoe had many other uses.

The priestly office was regarded with great favor, and great faith was reposed in the power of the priests to propitiate the idol-deities, and obtain from them benefits that were prayed for.

The astrologers, or kilo-lani, whose office it was to observe the heavens and declare the day that would bring victory in battle, were a class of men highly esteemed. So also were the kuhi-kuhi-puu-one, a class of priests who designated the site where a heiau should be built in order to insure the defeat of the enemy.

The kaka-olelo, or counselors who advised the alii in matters of government, were a class much thought of; so also were the warriors who formed the strength of the army in time of battle and helped to rout the enemy.

Net-makers (poe ka-upena) and those who made fishing lines (hilo-aha) were esteemed as pursuing a useful occupation. The mechanics who hewed and fashioned the tapa log, on which was beaten out tapa for sheets, girdles and loin-cloths for men and women were a class highly esteemed. There were a great many other actions that were esteemed as virtuous whether done by men and women or by the chiefs; all of them have not been mentioned.

CHAPTER 22

The Valuables And Possessions Of The Ancient Hawaiians

The feathers of birds were the most valued possessions of the ancient Hawaiians. The feathers of the mamo were more choice than those of the o o because of their superior magnificence when wrought into cloaks (ahu). The plumage of the i'iwi, apapane and amakihi were made into ahu-ula, cloaks and capes, and into mahi-ole, helmets.

The ahu-ula was a possession most costly and precious (makamae), not obtainable by the common people, only by the alii. It was much worn by them as an insignia in time of war and when they went into battle. The ahu-ula was also conferred upon warriors, but only upon those who had distinguished themselves and had merit, and it was an object of plunder in every battle.

Unless one were a warrior in something more than name he would not succeed in capturing his prisoner nor in getting possession of the ahu-ula and feathered helmet of a warrior. These feathers had a notable use in the making of the royal battle-gods.1 They were also frequently used by the female chiefs in making or decorating a comb called huli-kua, which was used as an ornament in the hair.

The lands that produced feathers were heavily taxed at the Makahiki time, feathers being the most acceptable offering to the Makahiki-idol. If any land failed to furnish the full tale of feathers due for the tax, the landlord was turned off (hemo). So greedy were the alii after fathers that there was a standing order (palala) directing their collection.

An ahu-ula made only of mamo feathers was called an alaneo and was reserved exclusively for the king of a whole island, alii ai moku; it was his kapa wai-kaua or battle-cloak. Ahu-ulas were used as the regalia of great chiefs and those of high rank, also for warriors of distinction who had displayed great prowess. It was not to be obtained by chiefs of low rank, nor by warriors of small prowess.

The carved whale-tooth, or niho-palaoa, was a decoration worn by high chiefs who alone were allowed to possess this ornament. They were not common in the ancient times, and it is only since the reign o-f Kamehameha2 I that they have become somewhat more numerous. In battle or on occasions of ceremony and display (hookahakaha) an alii wore his niho-palaoa. The lei-palaoa (same as the niho-palaoa) was regarded as the exclusive property of the alii.

The kahili, a fly-brush or plumed staff of state was the emblem and embellishment of royalty. Where the king went there went his kahili-bearer (paa-kahili), and where he stopped there stopped also the kahili-bearer. When the king slept the kahili was waved over him as a fly-brush. The kahili was the possession solely of the alii.

The canoe with its furniture was considered a valuable possession, of service both to the people and to the chiefs. By means of it they could go on trading1 voyages to other lands, engage in fishing, and perform many other errands.

The canoe was used by the kings and chiefs, as a means of ostentation and display. On a voyage the alii occupied the raised and sheltered platform in the waist of the canoe which was called the pola, while the paddle-men sat in the spaces fore and aft, their number showing the strength of the king's following.

Cordage and rope of all sorts (na kaula), were articles of great value, serviceable in all sorts of work. Of kaula there were many kinds. The bark of the hau tree was used for making lines or cables with which to haul canoes3 down from the mountains as well as for other purposes. Cord aha made from cocoanut fibre was used in sewing and binding together the parts of a canoe and in rigging it as well as for other purposes. Olona fibre was braided into (a four or six-strand cord called) lino, besides being made into many other things. There were many other kinds of rope (kaula).

Fishing nets (upena) and fishing lines (aho) were valued possessions. One kind was the papa-waha, which had a broad mouth; another was the aei (net with small meshes to take the opelu); the kawaa net (twenty to thirty fathoms long and four to eight deep, for deep sea fishing); the kuu net (a long net, operated by two canoes); and many other varieties.

Fish-lines, aho, were used in fishing for all sorts of fish, but especially for such fine large fish as the ahi and the kahala. The aho was also used in stitching together the sails (of matting) and for other similar purposes.

The ko'i, or stone ax, was a possession of value. It was used in hewing and hollowing canoes, shaping house-timbers and in fashioning the agriculture spade, the o o, and it had many other uses.

The house was esteemed a possession of great value. It was the place where husband and wife slept, where their children and friends met, where the household goods of all sorts were stored.

There were many kinds of houses: the mua for men alone, the noa, where men and women met, the halau for the shelter of long things, like canoes, fishing poles, etc., and there were houses for many other purposes.

Tapa was a thing of value. It was used to clothe the body, or to protect the body from cold during sleep at night. The malo also was a thing of great service, girded about the loins and knotted behind, like a cord, it was used by the men as a covering for the immodest parts.

Another article of value was the pau; wrapped about the loins and reaching nearly to the knees it shielded the modesty of the women.

Pigs, dogs and fowls were sources of wealth. They were in great demand as food both for chiefs and common people, and those who raised them made a good profit.

Any one who was active as a farmer or fisherman was deemed a .man of great wealth. If one but engaged in any industry he was looked upon as well off.

The man who was skilled in the art of making fish-hooks (ka-makau) was regarded as fore-handed. The fish-hooks of the Hawaiians were made of human bones, tortoise shell and the bones of pigs and dogs.

The names of the different kinds of hooks used in the ancient times would make a long list. The hoonoho4 was an arrangement of hooks made by lashing two bone hooks to one shank (they were sometimes placed facing each other and then again back to back).

The kikii (in which the bend of the hook followed a spiral; the lua-loa (sometimes used for catching the aku); the nuku (also called the kakaka. It consisted of a series of hooks attached to one line), the kea'a-wai-leia (for ulna). The bait was strewn in the water and the naked hook was moved about on the surface); the au-ku'u (a troll-hook, having two barbs, used to take the ulna); the maka-puhi (about the same as the au-ku'u, but with only one barb); the kai-anoa (used in the deep sea composed of two small hooks, without barbs; the omau (about the same as the kea'a-wai-leia but more open, with no barb, for the deep sea); the mana (a hook for the eel); the kohe-lua (also called kohe-lua-a-pa'a, a hook with two barbs); the hulu (having a barb on the outside); the kue (a very much incurved hook, used to take the oio, &c.); the hui-kala (a large hook with two barbs, one without and one within); the hio-hio (a minute hook of mother o' pearl, for the opelu); the lawa which was used for sharks.

Such were the names of the fish-hooks of the ancients, whether made of bone or of tortoise shell (ea). In helping to shape them the hard wood of the pua and the rough pahoehoe lava rock were used as rasps.

The oo (shaped like a whale-spade) was an instrument useful in husbandry. It was made of the wood of the ulei, mamane, omolemole, lapalapa (and numerous other woods including the alahe'e).

Dishes, ipu, to hold articles of food, formed part of the wealth, made of wood and of the gourd; umeke to receive poi and vegetable food; ipu-kai, bowls or soup-dishes, to hold meats and fish, cooked or raw, with gravies and sauces; pa-laau platters or deep plates for meats, fish, or other kinds of food; hue-wai bottle-gourds, used to hold water for drinking. Salt was reckoned an article of value.

A high value was set upon the cowry shell, leho,5 and the mother o' pearl, pa6, by the fishermen, because through the fascination exercised by these articles the octopus and the bonito were captured.

Mats, moena (moe-na), constituted articles of wealth, being used to bedeck the floors of the houses and to give comfort .to the bed.

A great variety of articles were manufactured by different persons which were esteemed wealth.

At the present time many new things have been imported from foreign countries which are of great value and constitute wealth, such as neat cattle, horses, the mule, the donkey, the goat, sheep, swine, dogs, and fowls.

New species of birds have been introduced, also new kinds of cloth, so that the former tapa-cloth has almost entirely gone out of use. There are also new tools, books, and laws, many new things.

CHAPTER 23

The Worship Of Idols

There was a great diversity as to cult among" those who worshipped idols in Hawaii nei, for the reason that one man had one god and another had an entirely different god. The gods of the aliis also differed one from another.

The women were a further source of disagreement; they addressed their worship to female deities, and the god of one was different from the god of another. Then too the gods of the female chiefs of a high rank were different from the gods of those of a lower rank.

Again the days observed by one man differed from those observed by another man, and the things that were tabued by one god differed from those tabued by another god. As to the nights observed by the alii for worship they were identical, though the things tabued were different with the different alii. The same was true in regard to the female chiefs.

The names of the male deities worshipped by the Hawaiians, whether chiefs or common people, were Ku, Lono, Kane, and Kanaloa; and the various gods worshipped by the people and the alii were named after them. But the names of the female deities we're entirely different.

Each man worshipped the akua that presided over the occupation or profession he followed, because it was generally believed that the akua could prosper any man in his calling. In the same way the women believed that the deity was the one to bring good luck to them in any work.

So also with the kings and chiefs, they addressed their worship to the gods who were active in the affairs that concerned them; for they firmly believed that their god could destroy the king's enemies, safeguard him and prosper him with land and all sorts of blessings.

The manner of worship of the kings and chiefs was different from that of the common people. When the commoners performed religious services they uttered their prayers themselves, without the assistance of a priest or of a kahu-akua. But when the king or an alii worshipped, the priest or the keeper of the idol uttered the prayers, while the alii only moved his lips and did not say a word. The same was true of the female chiefs; they did not utter the prayers to their gods.1

Of gods that were worshipped by the people and not by the chiefs the following are such as were worshipped by those who went up into the mountains to hew out canoes and timber: Ku-pulupulu2 Ku-ala-na-wao3, Ku-moku-halii4, Ku-pepeiao-loa, Ku-pepeiao-poko, Ku-ka-ieie, Ku-palala-ke, Ku-ka-ohia-laka.5 Lea6, though a female deity, was worshipped alike by women and canoe-makers..

Ku-huluhulu-manu was the god of bird-catchers, bird snares (poe-ka-manu)7, birds limers and of all who did featherwork..

Ku-ka-oo was the god of husbandmen.

Fishermen worshipped Ku-ula8 also quite a number of other fishing-gods. Hina-hele was a female deity worshipped both by women and fishermen.

Those who practiced sorcery and praying to death or anaana worshipped Ku-koae, Uli and Ka-alae-nui-a-Hina9. Those who nourished a god, an unihi-pili8, for instance or one who was acted upon by a deity, worshipped Kalai-pahoa.

Those who practiced medicine prayed to Mai-ola, Kapu-alakai and Kau-ka-hoola-mai were female deities worshipped by women and practitioners of medicine.

Hula-dancers worshipped Laka; thieves Makua-aihue; those who watched fish-ponds, Hau-maka-pu'u; warriors worshipped Lono-maka-ihe; soothsayers and those who studied the signs, of the heavens (kilokilo) worshipped the god Kuhimana.

Robbers worshipped the god Kui-alua; those who went to sea in the canoe worshipped Ka-maha-alii. There were a great many other deities regarded by the people, but it is not certain that they were worshipped. Worship was paid, however, to sharks, to dead persons, to objects celestial and objects terrestrial. But there were people who had no god, and who worshipped nothing; these atheists were called aia.

The following deities were objects of definite special worship by women: Lau-huki was the object of worship by the women who beat out tapa. La'a-hana was the patron deity of the women who printed tapa cloth. Pele and Hiiaka were the deities of certain women. Papa and Hoohoku11, our ancestors were worshipped by some as deities. Kapo and Pua had their worshippers. The majority of women, however, had no deity and just worshipped nothing.

The female chiefs worshipped as gods Kiha-wahine, Waka, Kalamaimu, Ahimu (or Wahimu), and Alimanoano. These deities were reptiles or Moo.

The deities worshipped by the male chiefs were Ku, Lono, Kane, Kana-loa, Kumaikaiki, Ku-maka-nui, Ku-makela, Ku-maka'aka'a, Ku-holoholo-i-kaua, Ku-koa, Ku-nui-akea, Ku-kaili-moku12, Ku-waha-ilo-o-ka-puni, Ulu, Lo-lupe this last was a deity commonly worshipped by many kings. Besides these there was that countless rout of (woodland) deities, kini-akua, lehu-akua, and mano-akua13 whose shouts were at times distinctly to be heard. They also worshipped the stars, things in the air and on the earth, also the bodies of dead men. Such were the objects of worship of the kings and chiefs.

The following gods were supposed to preside over different regions: Kane-hoa-lani (or Kane-wahi-lani) ruled over the heavens; the god who ruled over the earth was Kane-lu-honua; the god of the mountains was Ka-haku-o; of the ocean Kane-huli-ko'a.

The god of the East was Ke-ao-kiai, of the West Ke-aohalo, of the North Ke-ao-loa, of the South Ke-ao-hoopua. The god of winds and storms was Laa-mao-mao.

The god of precipices (pali) was Kane-holo-pali, of stones Kane-pohaku, of hard basaltic stone Kane-moe-ala, of the house Kane-ilok'a-hale14 (or Kane-iloko-o) , of the fire-place Kane-moe-lehu15, of fresh water Kane-wai-ola.

The god of the doorway or doorstep was Kane-hohoio16 (Kane-noio according to some). The number of the gods who were supposed to preside over one place or another was countless.

All of these gods, whether worshipped by the common people or by the alii, were thought to reside in the heavens. Neither commoner nor chief had ever discerned their nature; their coming and their going was unseen; their breadth, their length and all their dimensions were unknown.

The only gods the people ever saw with their eyes were the images of wood and of stone which they had carved with their own hands after the fashion of what they conceived the gods of heaven to be. If their gods were celestial beings, their idols should have been made to resemble the heavenly.

If the gods were supposed to resemble beings in the firmament, birds perhaps, then the idols were patterned after birds, and if beings on the earth, they were made to resemble the earthly.

If the deity was of the water, the idol was made to resemble a creature of the water, whether male or female17. Thus it was that an idol was carved to resemble the description of an imaginary being, and not to give the actual likeness of a deity that had been seen.

And when they worshipped, these images, made after the likeness of various things, were set up before the assembly of the people; and if then prayer and adoration had been offered to the true god in heaven, there would have been a resemblance to the popish manner of worship. Such was the ancient worship in Hawaii nei, whether by the common people or by the kings and chiefs. There was a difference, however, between the ceremonies performed by the common people at the weaning of a child and those performed by a king or chief on a similar occasion.

CHAPTER 24

Religious Observances Relating To Children

Here is another occasion on which worship was paid to the gods. After the birth of a child it was kept by the mother at the common house, called noa, and was nursed with her milk besides being fed with ordinary food.

When it came time for the child to be weaned, it was provided with ordinary food only, and was then taken from the mother and installed at the mua, or men's eating house. In regard to this removal of the child to the mua the expression was ua ka ia i mua. The eating tabu was now laid upon the child and it was no longer allowed to take its food in the company of the women.