Hawaiian

Antiquities (Mo`ōlelo Hawai`i)

By David Malo,

Honolulu Hawaiian Gazette Co., Ltd.

|

CHAPTER 29

Concerning The Ceremonies On The Death Of A King

On the death of a king, one who was at the head of the government, the ceremonies were entirely different from those performed on the death or any other alii whatsoever.

When the king was dead his heir was removed to another district, because that in which his death took place was polluted by the corpse.

The kuni1 priests took a part of the flesh of the dead king's body to be used as maunu in their incantations against those who had prayed him to death. The body was then taken to the mua2 house in the presence of the multitude and laid in the heiau, that it might be deified and transformed into an au-makua.

The ceremony was performed by the kahuna hui working under the rite of Lolupe,3 who was the god of the kahuna hui. It was believed that Lolupe was the deity who took charge of those who spoke ill of the king, consigning them to death, while the souls of those who were not guilty of such defamation he conducted to a place of safety (ola, life).

The service of the deity Lolupe was in one branch similar to the ceremony of kuni (or anaana) . The deification of the corpse and imparting godlike power to it was another branch of the priests' work, and was accomplished in the following manner.

The dead body was first wrapped in leaves of banana, wauke and taro, a rite which was called kapa lau, garment of leaves,

The body being thus completely enveloped, a shallow pit was dug and the body was buried therein about a foot below the surface, after which a fire was made on the ground the whole length of the grave.

This was kept constantly burning for about ten days, during which time the prayer called pule hui was continually recited. By that time the body had gone into decay and that night the bones were separated from the flesh and worship was performed to secure their deification after the following manner.4

After disinterment the bones were dissected out and arranged in order, those of the right side in one place, those of the left side in another, and, the skull-bones being placed on top, they were all made up into a bundle and wrapped in tapa.

The flesh which had gone to decay (pala-kahuki) and all the corruptible parts were called pela (pelapela, foul, unclean) and were cast into the ocean. It was by night that this pela was thrown into the ocean, on a tabu night. On that night no one from the village must go abroad or he might be killed by the men who were carrying forth the pela to consign it to the ocean.

After this was accomplished, the bones were put in position and arranged to resemble the shape of a man, being seated in the house until the day of prayer, when their deification would take place and they would be addressed in prayer by the kahunas of the mua. The period of defilement was then at an end; consequently the king's successor was permitted to return, and the apotheosis of the dead king being accomplished, he was worshipped as a real god6 (akua maoli.)

His successor then built for the reception of the bones a new heiau, which was called a hale poki, for the reason that in it was constructed a net-work to contain the bones, which, being placed in an upright position, as if they had been a man, were enshrined in the heiau as a god.

After this these bones continued to be a god demanding worship, and such a deity was called an au-makua. Common people were sometimes deified,5 but not in the same manner as were kings.

It was believed that it was the gods who led and influenced the souls of men. This was the reason why a real god, an akua maoli,6 was deemed to be a spirit, an uhane (or) this is the reason why it was said that the soul of the king was changed into a real god, (oia ka mea e olelo ai ka uhane i akua maoli.)

CHAPTER 30

The Medical Treatment Of The Sick

The medical treatment of the sick was a matter that belonged to the worship of the gods. When any one was seized with an illness a messenger was dispatched to the kahuna who practiced medicine, kahuna lapaau, taking with him an offering for mai-ola,1 the god of medicine.

When the messenger came before the kahuna the latter inquired regarding the disease, and having learned about it, before beginning the treatment, he forbade certain articles of food to the sick man.

The sick man must not eat the squid, moss, bêche de mer, loli, a certain fish called kualaka'i, nor the ina, wana, or haukeke, echini, nor the pipipi,2 the small sea-shell, Nerita, which is much eaten; all of these were forbidden, together with such other fish as the kahuna saw fit.

When the sick man had agreed to these restrictions, the kahuna began his treatment by administering some sort of potion,

After the treatment had continued a while, if the kahuna saw that the disease was about to let up he went and slept for a night in the mua3 that he might worship the god of medicine and so he might obtain a sign from the deity whether the sick man would recover or die.

He took with him to the mua a certain kind of moss (limu kala probably), also some pipipi shells, such things in fact as he had forbidden the man to partake of. If rain fell during the night, he regarded it as an unpropitious omen, in which case he spent another night there.

If, however, there was no rain that night the kahuna accepted the omen as favorable, and at daybreak he lighted a fire and performed the ceremony called pu-limu.4 He also baked a fowl, as an offering to the au-makua, of which only the kahuna ate. Two dogs also were baked, one for the mua, or men's house, and one for the noa or common sleeping house. Five sheets of tapa-cloth were used to cover the oven5 for the mua, and five to cover the oven for the noa. When the animals were baked, the men assembled at the mua and ate their portion of the sacrifice in company with the sick man, at the same time paying their worship to the god of medicine. Likewise the women in the noa house at the same time worshipped the female god of medicine. (On Molokai this was La'a-uli.)

After the ceremony of the pu-limu fire was over, the medical treatment of the patient was resumed. For a cathartic the juice of the koali (a convolvulus) was used; as an emetic was administered a vegetable juice called pi'i-ku (obtained from the fresh green stems of the ku-kui nut.) The enema was sometimes employed. Another remedy was the popo kapai.6 To reduce fever a draught of raw taro-juice or yam-juice, called apu-kalo or apu uhi,7 was found to be of service.

The next thing was to make a hut called hale hau, which was done with sticks of hau wood and was arched on top. The sick man was removed to this little hut and given a steam-bath, after which he was bathed in sea-water and then nourishment was administered. After this the ceremony of the pipipi fire was performed which was very similar to the pu-limu fire. A fowl was then sacrificed to the aumakua; a dog was baked for the mua and another for the noa. Five tapas were used in covering the oven for the mua and five to cover that for the noa. When all this had been done the prognosis of the sick one was again considered.

If it was seen that the patient was somewhat relieved (maha), the kahuna took the next step, which was to put the. patient to bed and perform the ceremony called hee mahola.8 If rain fell that night it was a bad omen and the kahuna then informed the sick man that he must die, because the omens derived from the hee mahola ceremony were adverse.

If, on the other hand, no rain fell that night the kahuna assured the man he would live. "The hee mahola has been attended with favorable omens. You will surely recover."

The following morning a fire, called ahi mahola, was lighted, the squid was cooked, and the prayer called pule hee, having been offered by the kahuna, the patient ate of the squid and thus ended the medical treatment and the incantations (hoomana.)

The treatment of a sick alii was different from that described above. Every time the alii took his medicine the kahuna offered prayer.

Only after the repetition of this prayer did the alii swallow his medicine.

The hee mahola9 ceremony was thought to be the thing to disperse (hehee) disease and bring healing to the body. When an alii had recovered from a malady he built a heiau, which was called either a Lono-puha10 or a kolea-muku.11 Such were the incantations in connection with the treatment of disease. When the work of the kahuna was done he was rewarded for his professional services.

Necromancy Necromancy, kilokilo uhane, was a superstitious ceremony very much practiced in Hawaii nei. It was a system in which bare-faced lying and deceit were combined with shrewd conjecture, in which the principal extorted wealth from his victims by a process of terrorizing, averring, for instance, that he had seen the wraith of the victim, and that it was undoubtedly ominous of his impending death. By means of this sort great terror and brooding horror were made to settle on the minds of certain persons.

The sorcerer, kahuna kilokilo, would announce that the wraith or astral body of a certain one had appeared to him in spectral form, in a sudden apparition, in a vision by day, or in a dream by night.

Thereupon he called upon the person whose wraith he had seen and stated the case, saying, "Today, at noon, while at my place, I saw your wraith. It was clearly yourself I saw, though you were screening your eyes.

"You were entirely naked, without even a malo about your loins. Your tongue was hanging out, you eyes staring wildly at me. You rushed at me and clubbed me with a stick until I was senseless. I was lucky to escape from you with my life.

"Your au-makua is wroth with you on this account. Perhaps he has taken your measure and found you out, and it is probably he who is rushing you on, and has led you to this action which you were seen to commit just now.

"Now is the proper time, if you see fit, to make peace with me, whilst your soul still tarries at the resting place of Pu'u-ku-akahi.1 Don't delay until your soul arrives at the brink of Ku-a-ke-ahu2 There is no pardon there. Thence it will plunge into Ka-paaheo,2 the place of endless misery."

At this speech of the kahuna kilokilo, the man whose soul was concerned became greatly alarmed and cast down in spirit, and he consented to have the kahuna perform the ceremony of kola, atonement, for him.

The kahuna then directed the man whose soul was in danger first to procure some fish as an offering at the fire-lighting (hoa ahi ana.) The fish to be procured were the kala, the weke, the he'e or octopus, the maomao, the palani, also a white dog, a white fowl, awa, and ten sheets of tapa to be used as a covering for the oven.

When these things had been made ready the kahuna proceeded to perform the ceremony of lighting the fire (for the offering) that was to obtain pardon for the man's sin (hala.)

The priest kept up the utterance of the incantation so long as the fire-sticks were being rubbed together; only when the fire was lighted did the incantation come to an end. The articles to be cooked were then laid in the oven, and it was covered over with the tapa.

When the contents of the oven were cooked and the food ready for eating, the kahuna kilokilo stood up and repeated the pule kala, or prayer for forgiveness :

After this prayer the one in trouble about his soul ate of the food and so did the whole assembly. This done, the kahuna said, "I declare the fire a good one (the ceremony perfect), consequently your sins are condoned, and your life is spared, you will not die." The kahuna then received his pay. If one of the chiefs found himself to be the victim of kilokilo, he pursued the same plan.

House-building was a matter that was largely decided by incantation (hooiloilo ia), there were also many other matters that were controlled by the same superstition, enterprises that could not succeed without the approval of kilokilo.

The makaula, or prophet, was one who was reputed to be able to see a spirit, to seize3 and hold it in his hand and then squeeze it to death. It was claimed that a makaula could discern the ghost of any person, even of one whose body was buried in the most secret place.

The makaula made a spirit visible by catching it with his hands; he then put it into food and fed it to others. Any one who ate of that food would see the spirit of that person, be it of the dead or of the living. The makaula did not deal so extortionately with his patrons as did the kilokilo-uhane.

The makaulas termed the spirits of living people.4 The oio comprised a great number (or procession) of spirits. A single spirit was a kakaola. The spirit of a person already dead was termed a kino-wailua.

The kaula5 prophets or foretellers of future events, were supposed to possess more power than other class of kahunas. It was said that Kane-nui-akea was the deity who forewarned the kaulas of such important events as the death of a king (alii ai au-puni), or of the overthrow of a government. These prophesies were called wanana.

The kaulas6 were a very eccentric class of people. They lived apart in desert places, and did not associate with people or fraternize with any one. Their thoughts were much taken up with the deity.

It was thought that people in delirium, frenzy, trance, or those in ecstasy (poe hewahewa) were inspired and that they could perceive the souls or spirits of men the same as did the kaulas or the makaulas, i.e., prophets and soothsayers. Their utterances also were taken for prophesies the same as were those of the kaula.

It was different, however, with crazy folks (pupule) and maniacs (hehena): they were not like prophets, soothsayers and those in a state of exaltation, i.e., the hewahewa. Crazy people and maniacs ate filth, and made an indecent exposure of themselves. Those in a state of exaltation, prophets and soothsayers did not act in this manner. There were many classes of people who were regarded as hewahewa, (i.e., cranky or eccentric.) This was also the case with all those who centered their thoughts on some fad or specialty (some of them were perhaps monomaniacs) some of them were hewahewa and some were not.

A spirit that enters into a person and then gives forth utterances is called an akua noho, that is an obsident deity, because it is believed that it takes possession of (noho maluna), the individual.

If, after death a man's bones were set in position along with an idol, and then his spirit came and made its residence with the bones, that was an akua noho, though specifically termed an unihipili2 or an aumakua.2

There was a large number of deities that took possession of people and through them made utterances. Pua and Kapo were deities of this sort. What they said was not true, but some persons were deceived by the speeches they made, but not everyone.

Kiha-wahine, Keawe-nui-kauo-hilo, Hia, and Keolo-ewa were akua noho who talked.

Pele and Hiiaka also were akua noho, as well as many other deities. But the whole thing was a piece of nonsense.

There were many who thought the akua noho a fraud, but a large number were persuaded of its truth. A great many people were taken in by the trickeries of the kahus of these obsident gods, but not everybody.

The kahus of the shark-gods would daub themselves with something like ihee-kai (turmeric or ochre mixed with salt water), muffle their heads with a red, or yellow, malo, and then squeak and talk in an attenuated, falsetto tone of voice. By making this kind of a display of themselves and by fixing themselves up to resemble a shark, they caused great terror, and people were afraid lest they be devoured by them. Some people were completely gulled by these artifices.

The kahus of the Pele deities also were in the habit of dressing their hair in such a way as to make it stand out at great length, then, having inflamed and reddened their eyes, they went about begging for any articles they took a fancy to, making the threat; "If you don't grant this request Pele will devour you. Many people were imposed upon in this manner, fearing that Pele might actually consume them.

From the fact that people had with their own eyes seen persons bitten by sharks, solid rocks, houses and human beings melted and consumed in the fires of Pele, the terror inspired by this class of deities was much greater than that caused by the other deities.

The majority of people were terrified when such deities as Pua3 and Kapo4 took possession of them as their kahu, for the reason that, on account of such obsession, a person would be afflicted with a swelling of the abdomen (opu-ohao) which was a fatal disease. Many deaths also were caused by obstruction of the bowels (pani), the result of their work. It was firmly believed that sucli deaths were caused by this class of deities.

Hiiaka5 caused hemorrhage from the head of the kahu of whom she took possession. Sometimes these deities played strange tricks when they took up their residence in any one ; they would, for instance, utter a call so that the voice seemed to come from the roof of the house.

The offices of the akua noho were quite numerous. Some of them were known to have uttered predictions that proved true, so that confidence was inspired in them; others were mere liars, being termed poo-huna-i-ke-aouli, which merely meant tricksters, (heads in the clouds.)

Faith in the akua noho was not very general; there were many who took no stock in them at all. Sometimes those who were skeptical asked puzzling questions (hoohuahua lau) of the akua noho, at the same time making insulting gestures (hoopoo-kahua) such as protruding the thumb between the fore and middle finger, or swelling out the cheek with the tongue doing this under the cover of their tapa robe; and if the akua noho, i.e., the kahuna, perceived their insolence they argued that he was a god of power (mana); but if he failed to detect them they ridiculed him.

Others who were skeptical would wrap up some article closely in tapa and then ask the akua noho, "What is this that is wrapped up in this bundle?" If the akua noho failed to guess correctly the skeptic had the laugh on the akua noho.

There was a large number, perhaps a majority of the people, who believed that these akua noho were utter frauds, while those who had faith in them were a minority.6

The consequence was that some of those who practiced the art of obsession, or hoonohonoho akua, were sometimes stoned to death, cruelly persecuted and compelled to flee away.

It is said that some practiced this art of hoonohonoho akua in order to gain the affections of some man or woman.

The practice of hoonohonoho akua was of hoary antiquity and a means of obtaining enormous influence in Hawaii nei.

Some of these miserable practices of the ancient Hawaiians were no doubt due to their devotion to worthless things, (idols?)

The house was a most important means of securing the wellbeing of husband, wife 'and children, as well as of their friends and guests.

It was useful as a shelter from rain and cold, from sun and scorching heat. Shiftless people oft times lived in unsuitable houses, claiming that they answered well enough.

Caves, holes in the ground and overhanging cliffs were also used as dwelling places by some folks, or the hollow of a tree, or a booth. Some people again sponged on those who had houses. Such were called o-kea-pili-mai1 or unu-pehi-iole.2 These were names of reproach. But that was not the way in which people of respectability lived. They put up houses of their own.

Their way was to journey into the mountains, and having selected the straightest trees, they felled them with an axe and brought them down as house-timber. The shorter trees were used as posts, the longer ones as rafters. The two end posts, called pou-hana,3 were the tallest, their length being the same as the height of the house.

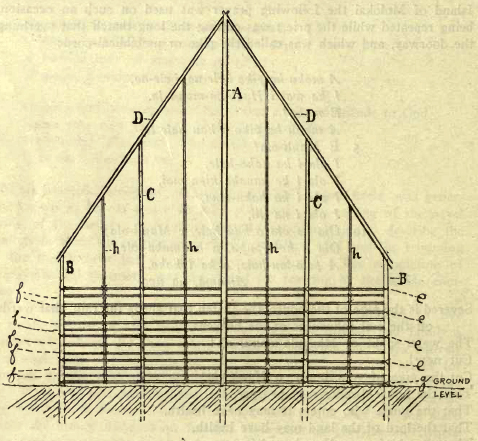

FIG. 1: Interior View of Gable of Hawaiian House

The posts standing alongside of the pouhana, called kukuna, rays, were not so high as the hana.4 The kaupaku, ridge-pole, was a rafter that ran the whole length of the house. On top of the ridge-pole was lashed a pole that was called the kua-iole. The upright posts within the house were called halakea. The small sticks to which the thatch was lashed were called a ho. This completes the account of the timbers and sticks of the house.

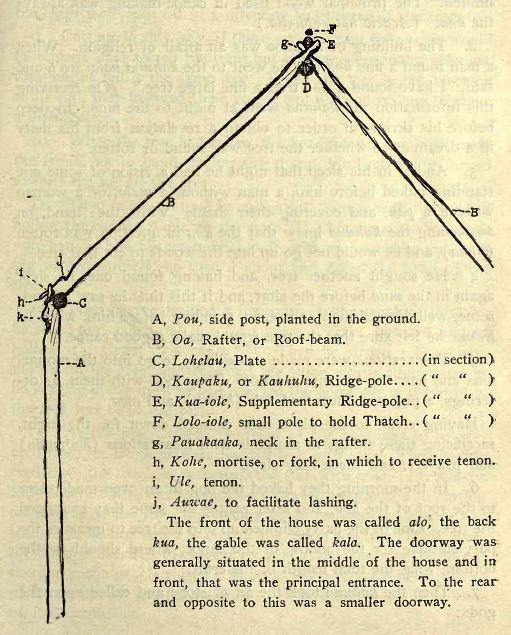

The house-posts, or pou, and the roof-beams, or o'a, were jointed to fit each other in the following manner. At the upper end and at the back of each post was fashioned a tenon (wahi oioi), and just below it and also on the back of the post, was cut a neck, leaving a chin-like projection above, called an auwae (chin.) Corresponding to this at the lower end of each rafter, or roof-beam (o'a), was fashioned a mortise in the shape of a prong to receive the tenon of the post; likewise at the same end, and at the back of the rafter, was cut another chin-like projection, or auwae. (Fig. 2.)

FIG. 2: Showing Tenon and Mortise joining Rafters, oa, of Roof to the Uprights, Pou, of the side of the house, also Ridge-pole, etc., in section

The corner posts having been first planted firmly in the ground, a line was stretched from one post to another at top and bottom to bring the posts in line with each other. The corner posts having been first planted firmly in the ground, a line was stretched from one post to another at top and bottom to bring the posts in line with each other.

Then the spaces between one post and another were measured and made equal, and all the posts on one side were firmly planted; then those on the other side; after which the plate, or lohelau, of the frame was laid on top of the posts from one corner post to another.

The posts were then lashed to the plates, lohelau, after which the tall posts at each end of the house, pouhana, were set up. This done, the kau-paku, ridge-pole, was laid in its place and lashed firmly with cord, and then the posts called halakea, uprights that supported the ridge-pole, were set inplace. After this the rafters, or o'a, were laid in position and measured to see at what length they must be cut off.

The rafters were then taken down and cut to the proper length. A neck having been worked at the upper end of each rafter, they were lashed firmly in position, after which the kua-iole, a sort of supplementary ridge-pole, was fastened above the real ridge-pole.

The different parts of the frame were now bound together with cord, and the small poles, called aho5 on which to bind the thatch, were lashed in place. This done, the work of putting on the thatching was begun. The thatch was sometimes of pili grass, sometimes sugar-cane leaves, and sometimes the leaves of the ti plant, according to circumstances.6

The next thing was to thatch and bonnet the ridge-pole, after which the opening for a doorway was made, and the door itself was constructed. In making a door the top and bottom pieces were rabbetted along the edge, and then the ends of the boards were set into the grooves.

Holes were drilled through the end along the groove with a drill of human bone, into which holes wooden pegs were then driven. The middle part was sewed together with cord. The door-frame was then constructed, having a grooved piece above and below in which the door was to slide. After this a fence, or pa} was put up to surround the house and its grounds.

On the completion of this part of the work, the kahuna pule, or priest was sent for to offer the prayer at the ceremony of trimming the thatch over the door. This prayer was called the pule kuwa7 and when it had been recited the man entered into his house and occupied it without further ado (me ka oluolu).

It was the custom among all respectable people, the chiefs, the wealthy, those in good standing (koikoi) and in comfortable circumstances to have their houses consecrated with some religious ceremony before living in them.

People who were of no account (lapuwale) did not follow this practice. They went in and occupied their houses without any such ceremony. Such folks only cared for a little shanty, anyway ; the fire-place was close to their head, and the poi-dish conveniently at hand; and so, with but one house, they made shift to get along.

People who were well off, however, those of respectability, of character, persons of wealth or who belonged to the alii class, sought to do everything decorously and in good style; they had separate8 houses for themselves and for their wives.

There was a special house for the man to sleep in with his wife and children (hale noa), also a number of houses specially devoted to different kinds of work, including one for the wife to do her work in (hale kua). There was the halau or canoe-house, the aleo9 a kind of garret or upper story, in which to stow things, also the amana, consisting of three houses built about a court.

This way of living corresponded with what the Hawaiians regarded as decent and respectable.

The bowls and dishes, ipu, used by the ancient Hawaiians in house-keeping were either of wood or of gourd, (pohue).

Those who were skilled in the art carved bowls and dishes out of different woods; but the kou was the wood generally used for this purpose. After the log had been fashioned on the outside it was either deeply hollowed out as a calabash, or umeke, or as a shallow dish or platter, an ipukai, to hold fish or meat. A cover also was hollowed out to put over the ipukai and the work was done.

The dish was then rubbed smooth within and without with a piece of coral, or with rough lava (oahi), then with pumice, or a stone called oio. After this charcoal was used, then bamboo leaf, and lastly it was polished with bread-fruit leaf and tapa – the same was done to the cover, and there was your dish. Sometimes a koko or net, was added as a convenient means of holding and carrying, and the work was then complete. The umeke was used for holding poi and vegetable food (ai) , the ipukai to hold meats and fish (ia).

The calabash, or pohue, was the fruit of a vine that was specially cultivated. Some were of a shape suited to be umeke, or poi containers, others ipukai, and others still to be used as hue-wai or water-containers. The pulp on the inside of the gourd was bitter; but there was a kind that was free from bitterness. The soft pulp within was first scraped out ; later, when the gourd had been dried, the inside was rubbed and smoothed with a piece of coral or pumice, and thus the calabash was completed. A cover was added and a net sometimes put about it.

In preparing a water-gourd, or hue-wai, the pulp was first rotted, then small stones were shaken about in it, after which it was allowed to stand with water in it till it had become sweet.

Salt was one of the necessaries and was a condiment used with fish and meat, also as a relish with fresh food. Salt was manufactured only in certain places. The women brought sea-water in calabashes or conducted it in ditches to natural holes, hollows, and shallow ponds (kaheka) on the sea-coast, where it soon became strong brine from evaporation. Thence it was transferred to another hollow, or shallow vat, where crystallization into salt was completed.

The papalaaii was a board on which to pound poi.

Water, which was one of the essentials of a meal, to keep one from choking or being burned with hot food, was generally obtained from streams (and springs), and sometimes by digging wells.

Vegetables (ai), animal food (i'a), salt and water – these are the essentials for the support of man's system.

Sharks' teeth were the means employed in Hawaii nei for cutting the hair. The instrument was called niho-ako-lauoho. The shark's tooth was firmly bound to a stick, then the hair was bent over the tooth and cut through with a sawing motion. If this method caused too much pain another resource was to use fire.

For mirrors the ancient Hawaiians used a flat piece of wood highly polished, then darkened with a vegetable stain and some earthy pigment. After that, on being thrust into the water, a dim reflection was seen by looking into it. Another mirror was made of stone. It was ground smooth and used after immersion in water.

The cocoanut leaf was the fan of the ancient Hawaiians, being braided flat. An excellent fan was made from the loulu-palm leaf. The handle was braided into a figured pattern. Such were the comforts of the people of Hawaii nei. How pitiable!

There are a great many improvements now-a-days. The new thing in houses is to build them of stone laid in mortar mortar is made of lime mixed with sand. In some houses the stones are laid simply in mud.

There are wooden houses covered with boards, and held together with iron nails; there are also adobe houses (lepo i omoo-mo ia); and houses made of cloth. Such are the new styles of houses introduced by the foreigners (haole).

For new dishes and containers, ipu, we have those made of iron, ipuhao, and of earthenware or china, ipu keokeo. But some of the new kinds of ware are not suited to fill the place of the run eke or calabash.

The new instrument for hair-cutting which the haole has introduced is of iron; it is called an upa, scissors or shears (literally to snap, to open, or to shut); a superior instrument this. There are also new devices in fans that will open and shut; they are very good.

The newly imported articles are certainly superior to those of ancient times.

The Hawaiian wa'a, or canoe, was made of the wood of the koa tree. From the earliest times the wood of the bread-fruit, kukui, ohia-ha, and wiliwili was used in canoe-making, but the extent to which these woods were used for this purpose was very limited. The principal wood used in canoe-making was always the koa. (Acacia heterophylla.)

The building of a canoe was an affair of religion. When a man found a fine koa tree he went to the kahuna kalai wa'a and said, "I have found a koa tree, a fine large tree." On receiving this information the kahuna went at night to the mua,1 to sleep before his shrine, in order to obtain a revelation from his deity in a dream as to whether the tree was sound or rotten.

And if in his sleep that night he had a vision of some one standing naked before him, a man without a malo, or a woman without a pan, and covering their shame with the hand, on awakening the kahuna knew that the koa in question was rotten (puha), and he would not go up into the woods to cut that tree.

He sought another tree, and having found one, he slept again in the mua before the altar, and if this time he saw a handsome, well dressed man or woman, standing before him, when he awoke he felt sure that the tree would make a good canoe.

Preparations were made accordingly to go into the mountains and hew the koa into a canoe. They took with them, as offerings, a pig, cocoanuts, red fish (kumu), and awa.

Having come to the place they camped down for the night, sacrificing these things to the gods with incantations (hoomana) and prayers, and there they slept.

In the morning they baked the hog in an oven made close to the root of the koa, and after eating the same they examined the tree. One of the party climbed up into the tree to measure the part suitable for the hollow of the canoe, where should be the bottom, what the total length of the craft.

Then the kahuna took the ax of stone and called upon the gods:

"O Ku-pulupulu2 Ku-ala-na-wao3 Ku-moku-halii4 Ku-ka-ieie;5 Ku-palalake,6 Ku-ka-ohia-laka''7

These were the male deities.

Then he called upon the female deities:

"O Lea8 and Ka-pua-o-alaka'i9 listen now to the ax. This is the ax that is to fell the tree for the canoe."

The koa tree was then cut down, and they set about it in the following manner: Two scarfs were made about three feet apart, one above and one below, and when they had been deepened, the chips were split off in a direction lengthwise of the tree.

Cutting in this way, if there was but one kahuna, it would take many days to fell the tree; but if there were many kahunas, they might fell it the same day. When the tree began to crack to its fall, they lowered their voices and allowed no one to make a disturbance.

When the tree had fallen, the head kahuna mounted upon the trunk, ax in hand, facing the stump, his back being turned toward the top of the tree.

Then in a loud tone he called out, "Smite with the ax and hollow the canoe! Give me the malo!"10 Thereupon the kahuna's wife handed him his ceremonial malo, which was white; and, having girded himself, he turned about and faced the head of the tree.

Then having walked a few steps on the trunk of the tree, he stood and called out in a loud voice, "Strike with the ax and hollow it! Grant us a canoe!''11 Then he struck a blow with the ax on the tree, and repeated the same words again; and so he kept on doing until he had reached the point where the head of the tree was to be cut off.

At the place where the head of the tree was to be severed from the trunk he wreathed the tree with ie-ie. Then having severed from the trunk he wreathed the tree with ie-ie, (Freycinetia Scandens). Then having repeated a prayer appropriate to cutting off the top j0f the tree, and having again commanded silence and secured it, he proceeded to cut off the top of the tree. This done, the kahuna declared the ceremony performed, the tabu removed; thereupon the people raised a shout at the successful performance of the ceremony, and the removal of all tabu and restraint in view of its completion.

Now began the work of hewing out the canoe, the first thing being to taper the tree at each end, that the canoe might be sharp at stem and stern. Then the sides and bottom (kua-moo) were hewn down and the top was flattened (hola). The inner parts of the canoe were then planned and located by measurement.

The kahuna alone planned out and made the measurements for the inner parts of the canoe. But when this work was accomplished the restrictions were removed and all the craftsmen took hold of the work (noa ka oihana o ka wa'a).

Then the inside of the canoe was outlined and the pepeiao, brackets, on which to rest the seats, were blocked out, and the craft was still further hewn into shape. A maku'u,12 or neck, was wrought at the stern of the canoe, to which the lines for hauling the canoe were to be attached.

When the time had come for hauling the canoe down to the ocean again came the kahuna to perform the ceremony called pu i ka wa'a, which consisted in attaching the hauling lines to the canoe-log. They were fastened to the maku'u. Before doing this the kahuna invoked the gods in the following prayer:

"O Ku-pulupulu, Ku-ala-na-wao, and Ku-moku-halii! (look you after this canoe. Guard it from stem to stern until it is placed in the halau)." After this manner did they pray.

The people now put themselves in position to haul the canoe. The only person who went to the rear of the canoe was the kahuna, his station being about ten fathoms behind it. The whole multitude of the people went ahead, behind the kahuna no one was permitted to go ; that place was tabu, strictly reserved for the god of the kahuna kalai wa'a.

Great care had to be taken in hauling the canoe. Where the country was precipitous and the canoe would tend to rush down violently, some of the men must hold it back lest it be broken; and when it got lodged some of them must clear it. This care had to be kept up until the canoe had reached the halau, or canoe-house.

In the halau the fashioning of the canoe was resumed. First the upper part was shaped and the gunwales were shaved down; then the sides of the canoe from the gunwales down were put into shape. After this the mouth (waha) of the canoe was turned downwards and the iwi kaele, or bottom, being exposed, was hewn into shape. This done, the canoe was again placed mouth up and was hollowed out still further (kupele maloko). The outside was then finished and rubbed smooth (anai ia). The outside of the canoe was next painted black (paele ia).13 Then the inside of the canoe was finished off by means of the koi-owili, or reversible adze (commonly known as the kupa-ai ke'e).

After that were fitted on the carved pieces (na laau) made of ahakea or some other wood. The rails, which were fitted on to the gunwales and which were called mo'o (lizards) were the first to be fitted and sewed fast with sinnet or aha.

The carved pieces, called manu, at bow and stern, were the next to be fitted and sewed on, and this work completed the putting together of the body of the canoe (ke kapili ana o ka wa'a. It was for the owner to say whether he would have a single or double

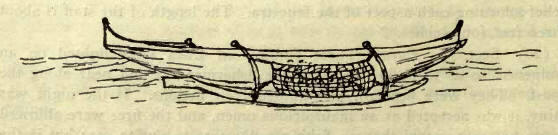

If it was a single canoe or kaukahi, (cross-pieces), and a float, called ama, were made and attached to the canoe to form the outrigger.

The ceremony of lolo-wa'a, consecrating the canoe, was the next thing to be performed in which the deity was again approached with prayer. This was done after the canoe had returned from an excursion out to sea.

The canoe was then carried into the halau where were lying the pig, the red fish, and the cocoanuts that constituted the offering spread out before the kahuna. The kahuna kalai-wa'a then faced towards the bows of the canoe, where stood its owner, and said, "Attend now to the consecration of the canoe (lolo ana o ka wa'a), and observe whether it be well or ill done."

Then he prayed :

When the kahuna had finished his prayer he asked of the owner of the canoe, ''How is this service, this service of ours?" Because if any one had made a disturbance or noise, or intruded upon the place, the ceremony had been marred and the owner of the canoe accordingly would then have to report the ceremony to be imperfect. And the priest would then warn the owner of the canoe, saying, "Don't you go in this canoe lest you meet with a fatal accident."

If, however, no one had made a disturbance or intruded himself while they had been performing the lolo17 ceremony, the owner of the canoe would report "our spell is good" and the kahuna would then say, "You will go in this canoe with safety, because the spell is good" (maikai ka lolo ana). If the canoe was to be rigged as part of a double canoe the ceremony and incantations to be performed by the kahuna were different. In the double canoe the iakos used in ancient times were straight sticks. This continued to be the case until the time of Keawe,19 when one Kanuha invented the curved iako and erected the upright posts of the the pola.

When it came to making the lashings for the outrigger of the canoe, this was a function of the utmost solemnity. If the lashing was of the sort called kumu-hele, or kumu-pau it was even then tabu; but if it was of the kind called kaholo, or Luukia (full name pa-u o Luukia), these kinds, being reserved for the canoes of royalty, were regarded as being in the highest degree sacred, and to climb upon the canoe, or to intrude at the time when one of these lashings was being done, was to bring down on one the punishment of death.

When the lashings of the canoe were completed a covering of mat was made for the canoe (for the purpose of keeping out the water) which mat was called a pa-u.24

The mast (pou or kia) was set up in the starboard canoe, designated as ekea, the other one being called ama. The mast was stayed with lines attached to its top. The sail of the canoe, which was called la, was made from the leaves of the pandanus, which were plaited together, as in mat-making.

The canoe was furnished with paddles, seats, and a bailer. There were many varieties of the wa'a. There was a small canoe called kioloa.19 A canoe of a size to carry but one person was called a koo-kahi, if to carry two a koo-lua, if three a koo-kolu, and so on to the the koo-wahi for eight.

The single canoe was termed a kau-kahi, the double canoe a kau-lua. In the time of Kamehameha I a triple canoe named Kaena-kane, was constructed, such a craft being termed a pu-kolu. If one of the canoes in a double canoe happened to be longer than its fellow, the composite craft was called a ku-e-e.

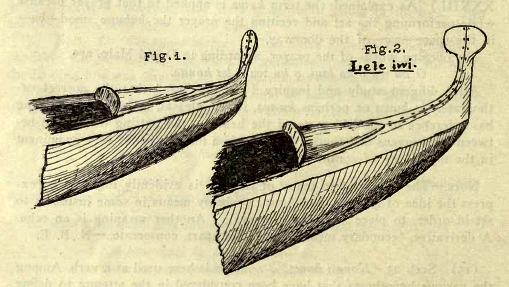

In case the carved bow-piece, manu-ihu, was made very broad the canoe was called a lele-iwi.20 (See fig: 2.) A canoe that was short and wide was called a pou. Canoes were designated and classified after some peculiarity. If the bow was very large the canoe would be termed ihu-nui;22 one kind was called kupeulu.

In the reign of Kamehameha I were constructed the canoes called peleleu.23 They were excellent craft and carried a great deal of freight. The after part of these crafts were similar in construction to an ordinary vessel (i.e. was decked over). It was principally by means of such craft as these that Kamehameha succeeded in transporting his forces to Oahu when he went to take possession of that part of his dominion when he was making his conquests.

In these modern times new kinds of sea-going craft have multiplied, large, fine vessels they are, which we call moku (an island, a piece cut off).

A ship was like a section of the earth quietly moving through the water. On account of their great size, when the first ships arrived here, people flocked from remote districts to view them. Great were the benefits derived from these novel craft, the like of which had never been seen before.

Some of these vessels, or moku, were three-masted, some two-masted, some schooner-rigged, and some had but one mast.

The row boat, or wa'a-pa (wa'a-pa'a), is one of this new kind of craft. But even some of these new vessels, including row-boats, sometimes perish at sea.

It is not, however, so common an occurrence for this to happen to them as it used to be for canoes to founder in every part of this ocean.

The efforts of the kings to secure offspring were associated with the worship of the gods; but these religious performances related only to the first born,1 because such held the highest rank as chiefs.

In the case of high chiefs the affair was conducted as follows; a high chief of the opposite sex was sought out and, after betrothal, the two young people were at first placed (hoonoho)2 under keepers in separate establishments, preparatory to pairing for offspring, the purpose being to make the offspring of the highest possible rank. Worship was paid to the gods, because it was firmly believed that the genius, power and inspiration (mana) of a king was like that of a god.

When the princess had recovered from her infirmity and had purified herself in the bath, she was escorted to the tent made of tapa, which had been set up in an open place in the sight of all the people.

To her now came the prince, bringing with him his akua kaai.3 This akua kaai was set up outside of the tent, where were keeping watch the multitude of the people, and the assembled priests were uttering incantations and praying to the gods that the union of the two chiefs might prove fruitful.

When the princess has returned from her bath, the prince goes in unto her and remains in her company perhaps until evening, by which time the ceremony called hoomau keiki is completed. Then the prince takes his leave, the princess returns home, the people disperse, the kahunas depart, the chiefs retire and the tent is taken down. This ceremony is enacted only in the case of the very highest chiefs, never those of inferior rank.

If after this it is found that the princess is with child, there is great rejoicing among all the people that a chief of rank has been begotten. If the two parents are of the same family, the offspring will be of the highest possible rank.4

Then those who composed meles (haku mele5) were sent for to compose a mele inoa that should eulogise and blazon the ancestry of the new chief to-be, in order to add distinction to him when he should be born.

And when the bards had composed their meles satisfactorily (a holo6 na mele), they were imparted to the hula dancers to be committed to memory. It was also their business to decide upon the attitudes and gestures, and to teach the inoa to the men and women of the hula (i.e. the chorus).

After that the men and women of the hula company danced and recited the mele inoa of the unborn chief with great rejoicing, keeping it up until such time as the prince was born ; then the hula-performances ceased.

When the time for the confinement of the princess drew near the royal midwives (themselves chiefesses) were sent for to take charge of the accouchement and to look after the mother. As soon as labor-pains set in an offering was set before the idol (the akua kaai named Hulu), because it was believed to be the function of that deity to help women in labor.

When the expulsory pains became very frequent,7 the delivery was soon accomplished; and when the child was born, the father's akua kaai was brought in attended by his priest. If the child was a girl, its navel-string was cut in the house; but if a boy, it was carried to the heiau, there to have the navel-string cut in a ceremonious fashion.

When the cord had first been tied with olona, the kahuna, having taken the bamboo (knife), offered prayer, supplicating the gods of heaven and earth and the king's kaai gods, whose images were standing there. The articles constituting the offering, or mohai, were lying before the king, a pig, cocoanuts, and a robe of tapa. The king listened attentively to the prayer of the kahuna, and at the right moment, as the kahuna was about to sever the cord, he took the offerings in his hands and lifted them up.

Thereupon the kahuna prayed as follows:

The kahuna then took the bamboo between his teeth and split it in two (to get a sharp cutting edge), saying:

Thereupon he applies the bamboo-edge and severs the cord; and, having sponged the wound to remove the blood (kupenu, with a pledget of soft olona fibre, oloa, the kahuna prays:

When the prayer of the kahuna was ended, the royal father of the child himself offered prayer to the gods:

The king then dashed the pig against the ground and killed it as an offering to the gods, and the ceremonies were ended.

The child was then taken back to the house and was provided with a wet nurse who became its kahu. Great care was taken in feeding the child, and the kahus were diligent in looking after the property collected for its support. The child was subject to its kahu until it was grown up. The young prince was not allowed to eat pork until he had been initiated into the temple service, after which that privilege was granted him. This was a fixed rule with princes.

When the child had increased in size and it came time for him to undergo the rite of circumcision, religious ceremonies were again performed. The manner of performing circumcision itself was the same as in the case of a child of the common people, but the religious ceremonies were more complicated.

When the boy had grown to be of good size a priest was appointed to be his tutor, to see to his education and to instruct him in matters religious; and when he began to show signs of incipient manhood, the ceremony of purification (huikala) was performed, a heiau was built for him, and he became a temple worshipper (mea haipule) on his own account. He was then permitted to eat of pork that had been baked in an oven outside of the heiau, but not of that which had been put to death by strangulation, in the manner ordinarily practiced, and then baked in an oven outside of the heiau without religious rites. His initiation into the eating of pork was with prayer.

Such was the education and bringing up of a king's son. The ceremonies attendant on the education and bringing up of the daughters were not the same as those above described; but the ceremony of cutting the navel-string, as well as some other ceremonies, was performed on them. The ceremonies, however, were not of the same grade as in the case of the first born, because it was esteemed as a matter of great importance by kings, as well as by persons of a religious turn of mind, that the first born should be devoted to the service of the gods.

The birth of a first child was a matter of such great account that after such birth chiefish mothers and women of distinction, whether about court or living in the back districts, underwent a process of purification (hooma'ema'e) in the following manner.

After the birth of the child the mother kept herself separate from her husband and lived apart -from him for seven days ; and when her discharge was staunched she returned to her husband's house.

During this period she did not consort with her husband, nor with any other man; but there was bound about her abdomen a number of medicinal herbs, which were held in place by her malo. This manner of purification for women after childbirth was termed hoopapa.

While undergoing the process of purification the woman did not take ordinary food, but was supported on a broth made from the flesh of a dog. On the eighth day she returned to her husband, the discharge (walewale) having by that time ceased to flow.

The woman, however, continued her purification until the expiration of an anahulu, ten days, by which time this method of treatment, called hoopapa, was completed. After that, in commemoration of the accomplishment of her tabu, the woman's hair was cut for the first time.8

Thus it will appear that from the inception of her pregnancy, she had been living in a state of tabu, or religious seclusion, abstaining from all kinds of food that were forbidden by her own or her husband's gods. It was after this prescribed manner that royal mothers, and women of rank, conducted themselves during the period of their first pregnancy. Poor folks did not follow this regime.

The women of the poor and humble classes gave birth to their children without paying scrupulous attention to matters of ceremony and etiquette (me ka maewaewa ole).

CHAPTER 36

The makahiki1 was a time when men, women and chiefs rested and abstained from all work, either on the farm or elsewhere. It is was a time of entire freedom from labor.

The people did not engage in the usual religious observances during this time, nor did the chiefs; their worship consisted in making offerings of food. The king himself abstained from work on the makahiki days.

There were four days, during which every man, having provided himself with the means of support during his idleness, reposed himself at his own house.

After these four days of rest were over, every man went to his farm, or to his fishing, but nowhere else, (not to mere pleasure-seeking), because the makahiki tabu was not yet ended but merely relaxed for those four days. It will be many days before the makahiki will be noa, there being four moons in that festival, one moon in Kau, and three moons in Hooilo.

The makahiki period began in Ikuwa, the last month of the period called Kau, and the month corresponding to October, and continued through the first three months of the period Hooilo, to-wit: Welehu, Makalii and Kaelo, which corresponded with November, December and January. During these four months, then, the people observed makahiki, refraining from work and the ordinary religious observances.

There were eight months of the year in which both chiefs and commoners were wont to observe the ordinary religious ceremonies, three of them being the Hooilo months of Kaulua, Nana, and Welo, corresponding to February, March and April; and five, the Kau months of Ikiiki Kaaona, Hinaiaeleele, Hilinaehu, and Hilinama, which corresponded to May, June, July, August and September.

During these eight months of every year, then, the whole people worshipped, but rested during the four Makahiki months. In this way was the Makahiki observed every year from the earliest times.

Many and diverse were the religious services which the alii and the commoners offered to their gods. Great also was the earnestness and sincerity (hoomaopopo maoli ana) with which these ancients conducted their worship of gods.

Land was the main thing which the kings and chiefs sought to gain by their prayers and worship (hoomana), also that that they might enjoy good health, that their rule might be established forever, and that they might have long life. They prayed also to their gods for the death of their enemies.

The common people, on the other hand, prayed that the lands of their alii might be increased, that, their own physical health might be good, as well as the health of their chiefs. They prayed also that they might prosper in their different enterprises. Such was the burden of their prayers year after year.

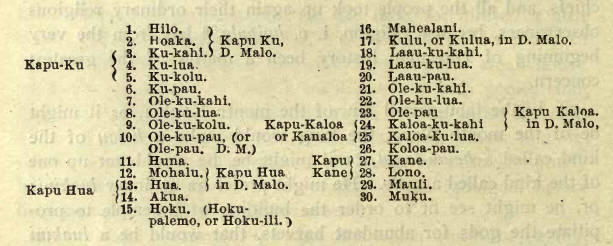

During the tabu-days of Ku (the 3rd, 4th, and 5th of each month), in the month of Ikuwa (corresponding to October) flags were displayed from the heiaus (temples), to announce the coming of the makahiki festival; the services at the royal heiaus were suspended, and the chiefs and people who were wont to attend the worship, betook themselves to sports, games and the pursuit of pleasure. But the priests, the kahus (keepers) of images and the ruler at the head of the government pursued another course.

There were twelve months, consisting of nine times forty days, in a year; and four tabu-periods, or pules, in each month. Two nights and a day would be tabu, and at the end of the second night the tabu would be off.

During the tabu of Hua, (the 13th, and 14th days), in the month Ikuwa, was performed the ceremony of breaking the cocoanut2 of the king. This was part of the observance of Makahiki and was to propitiate the deity. When this had been done he went to his pleasures.

When the Ku-tabu of the month of Welehu had come it went by without religious service; but on the Hua-tabu of that month the commoners, and the chiefs of lower ranks performed the ceremony of breaking the cocoanut-dish. The temples were then shut up and no religious services were held.

In the succeeding days the Makahiki-taxes were gotten ready against the coming of the tax-collectors for the districts known as okanas, pokos, kalanas, previously described, into which an island was divided.

It was the duty of the konohikis to collect in the first place all the property which was levied from the loa for the king; each konohiki also brought tribute for his own landlord, which was called waiwai maloko.

On Laaukukahi (18th day), the districts were levied on for the tax for the king, tapas, pa-us, malos, and a great variety of other things.

Contributions of swine were not made, but dogs were contributed until the pens were full of them. The alii did not eat fresh pork during these months, there being no temple service. They did, however, eat such pork as had previously been dressed and cured while services were being held in the temples.

On Laaupau, (20th day), the levying of taxes was completed, and the property that had been collected was displayed before the gods (hoomoe ia): and on the following day (Olekukahi), the king distributed it among the chiefs and the companies of soldiery throughout the land.

The distribution was as follows: first the portion for the king's gods was assigned, that the kahus of the gods might have means of support; then the portion of the king's kahunas; then that for the queen and the king's favorites, and all the aialo who ate at his table. After this, portions were assigned to the remaining chiefs and to the different military companies.

To the more important chiefs who had many followers was given a large portion; to the lesser chiefs, with fewer followers, a smaller portion. This was the general principle on which the division of all this property was made among the chiefs, soldiery (puali) and the aialo.

No share of this property, however, was given to the people. During these days food was being provided against the coming of the Makahiki, preparations of cocoanut mixed with taro or breadfruit, called kulolo, sweet breadfruit-pudding, called pepeiee, also poi, bananas, fish, awa, and many other varieties of food in great abundance.

On the evening of the same day, Olekukahi, the feather gods were carried in procession, and the following evening, Olekulua, the wooden gods were in turn carried in procession. Early the following morning, on the day called Olepau, (23rd), they went at the making of the image of the Makahiki god, Lonomakua This work was called ku-i-ke-pa-a.

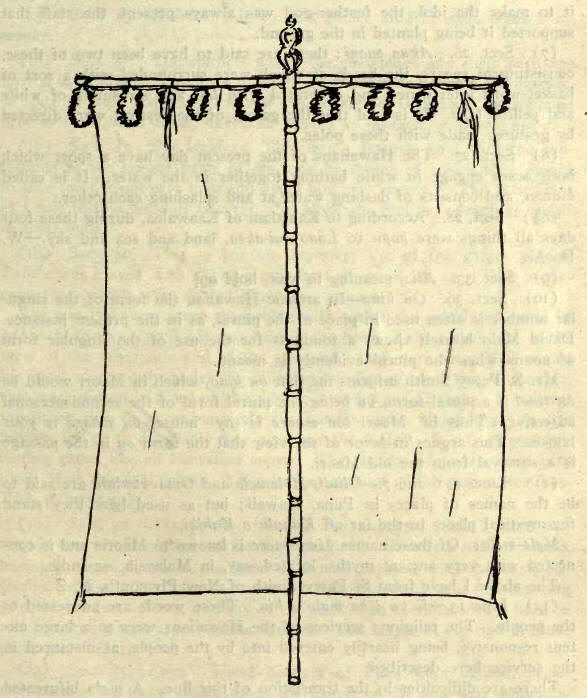

This Makahiki-idol was a stick of wood having a circumference of about ten inches and a length of about two fathoms. In form it was straight and staff-like, with joints carved at intervals resembling a horse's leg; and it had a figure carved at its upper end.

A cross-piece was tied to the neck of this figure, and to this cross-piece, kea, were bound pieces of the edible pala3 fern. From each end of this cross-piece were hung feather leis that fluttered about, also feather imitations of the kaupu5 bird, from which all the flesh and solid parts had been removed.

The image was also decorated with a white tapa4 cloth made from wauke kakahi, such as was grown at Kuloli. One end of this tapa was basted to the cross-piece, from which it hung down in one piece to a length greater than that of the pole. The width of this tapa was the same as the length of the cross-piece, about sixteen feet.

The work of fabricating this image was called kuikepaa.6 The following night the chiefs and people bore the image in grand procession, and anointed it with cocoanut oil. Such was the making of the Makahiki god. It was called Lonomakua (father Lono), also the akua loa. This name was given it because it made the circuit of the island.

Captain Cook was named Lono after this god, because of the resemblance the sails of his ship bore to the tapa of the god.

There was also an akua poko (short god); so called because it was carried only as far as the boundary of the district and then taken back; also an akua paani7 (god of sports), which accompanied the akua loa in its tour of the island and was set up to preside at the assemblies for boxing, wrestling, and other games. By evening of that same day (Olepau), the making of the akua loa was completed.

On the morning following the night of Olepau, fires were lighted along the coast all round the island, and everybody, people and chiefs, went to bathe and swim in the ocean, or in fresh water; after which they came to bask and warm themselves about the fires, for the weather was chilly. The bathing was continued until daylight. This practice was called hiuwai.8

The Makahiki tabu began on sunrise of that same day, Kaloa-kukahi, (the 24th). Everybody rested from work, scrupulously abstaining even from bathing in the ocean or in a fresh water stream. One was not permitted to go inland to work on his farm, nor to put to sea, for the purpose of fishing in the ocean. They did no work whatever during those days. Their sole occupation was to eat and amuse themselves. This they continued to do for four days.

That same day (Kaloa-kukahi) the Makahiki god came into the district it had to be carried by men, however. The same day also the high priest at Kaiu (said to be a place in Waimea, where was a famous shrine) began the observance of a tabu which was to continue for five days. His eyes were blindfolded with tapa during that whole time, and only at its expiration were they unbound to allow him to look upon the people.

By the time the Makahiki god had arrived, the konohikis set over the different districts and divisions of the land, known as kalanas, okanas, pokos, and ahu-puaas, had collected the taxes for the Makahiki, and had presented them as offerings to the god; and so it was done all round the island.

This tax to the Makahiki god consisted of such things as feathers of the oo, mamo, and i'iwi, swine, tapas and bundles of pounded taro, paiai, to serve as food for those who carried the idol. On the large districts a heavy tax was imposed, and on the smaller ones a lighter tax. If the tax of any district was not ready in time, the konohiki was put off his land by the tax-collector. The konohiki was expected to have all the taxes of the district collected beforehand and deposited at the border of the ahu-pua'a, where was built an altar.

In making its circuit of the island the akua-loa always moved in such a direction as to keep the interior of the island to its right; the akua-poko so as to keep it on the left; and when the latter had reached the border of the district it turned back. During the progress of the Makahiki god the country on its left, i.e., towards the ocean, was tabu; and if any one trespassed on it he was condemned to pay a fine, a pig of a fathom long; his life was spared.

As the idol approached the altar that marked the boundary of the ahu-puaa a man went ahead bearing two poles, or guidons, called alia.

The man planted the alia, and the idol took its station behind them. The space between the alia was tabu, and here the konohikis piled their hookupu, or offerings, and the tax-collectors, who accompanied the akua-makahiki, made their complaints regarding delinquent tax-payers. All outside of the alia was common ground (noa).

When enough property had been collected from the land to satisfy the demands of the tax-collector, the kahuna who accompanied the idol came forward and uttered a prayer to set the land free. This prayer was called Hainaki and ran as follows:

By this ceremony the land under consideration was sealed as free. The idol was then turned face downwards and moved on to signify that no one would be troubled, even though he ventured on the left hand side of the road, because the whole district had been declared free from tabu, noa. But when the idol came to the border of the next ahu-puaa the tabu of the god was resumed, and any person who then went on the left hand side of it subjected himself to the penalties of the law. Only when the guardians of the idols declared the land free did it become free.

This was the way they continued to do all round the island; and when the image was being carried forward its face looked back, not to the front.

When the Makahiki god of the alii came to where the chiefs were living they made ready to feed it. It was not, however, the god that ate the food, but the man that carried the image. This feeding was called hanai-pu and was done in the following manner.

The food, consisting of kulolo, hau, preparations of arrowroot, bananas, cocoanuts and awa, (for such were the articles of food prepared for the Makahiki god), was made ready beforehand, and when the god arrived at the door of the alii's house, the kahunas from within the house, having welcomed the god with an aloha, uttered the following invocation:

Welcome now to you, O Lono! (E weli ia oe Lono, ea!)

Then the kahuna and the people following the idol called out, Nauane, nauane, moving on, moving on. Again the kahunas from within the house called out, Welcome to you, O Lono! and the people with the idol answered, moving on, moving on (Nauane, nauane,) Thereupon the kahunas from within the house called out, This way, come in! (Hele mai a komo, hele mai a, komo.)

Then the carrier of the idol entered the house with the image, and after a prayer by the kahuna, the alii fed the carrier of the image with his own hands, putting the food into the man's mouth, not so much as suffering him to handle it, or to help himself in the least. When the repast was over the idol was taken outside.

Then the female chiefs brought a malo, and after a prayer by the kahuna, they proceeded to gird it about the god. This office was performed only by the female chiefs and was called Kai-olo-a.

By this time the god had reached the house of the king, the means for feeding the god were in readiness, and the king himself was sitting in the mystic rite of Lono (e noho ana ke alii nui i ka lui o Lono); and when the feeding ceremony of hanaipu had been performed the king hung about the neck of the idol a niho-palaoa. This was a ceremony which the king performed every year. After that the idol continued on its tour about the island.

That evening the people of the villages and from the country far and near assembled in great numbers to engage in boxing matches, and in other games as well, which were conducted in the following manner.

The whole multitude stood in a circle, leaving an open space in the centre for the boxers, while chiefs and people looked on.

As soon as the tumult had been quieted and order established in the assembly, a number of people on one side stood forth and began a reviling recitative: "Oh you sick one, you'd better lie abed in the time of Makalii (the cold season). You'll be worsted and thrown by the veriest novice in wrestling, and be seized per lapides,17 you bag of guts you."

Then the people of the other side came forward and, standing in the midst of the assembly, reviled the first party. Thereupon the two champions proceeded to batter each other; and whenever either one was knocked down by the other, the whole multitude set up a great shout.

This performance was a senseless sport, resulting in wounds and flowing of blood. Some struggled and fought, and some were killed.

The next day, Koloa-kulua (25th), was devoted to boxing, holua, sledding, rolling the maika stone, running races (kukini), sliding javelins (pahee),18 the noa or puhenehene and many other games, including hula dancing.

These sports were continued the next day, which was Kaloa-pau, and on the morning of the following day, Kane, the akua-poko,19 reached the border of the district, traveling to the left, and turning back, arrived home that evening. The akua-loa kept on his way about the island with the god of sport (akua-paani.)

The return of the akua-poko was through the bush and wild lands above the travelled road, and they reacehd the temple sometime that evening. Along its route the people came trooping after the idol, gathering pala fern and making backloads of it. It is said that on the night of Kane the people gathered this fern from the woods as a sign that the tabu was taken from the cultivated fields.

The keepers of the god Kane, whether commoners or chiefs, made bundles of luau that same night, and having roasted them on embers, stuck them up on the sides of their houses, after which their farms were relieved from tabu, and they got food from them.

The kahus of Lono also did the same thing on the night Lono (28th), after which their farms also were freed from tabu and they might take food from them. Likewise the kahus of the god Kanaloa did the same thing on the night of Mauli (29th). This ceremony was called o-luau, and after its performance the tabu was removed from the cultivated fields, so that the people might farm them. But this release from tabu applied only to the common people; the king and chiefs practiced a different ceremony.

With the alii the practice was as follows: On the return of the akua-poko, which was on the day Kane (27th), pala fern was gathered; and that night the bonfire of Puea20 was lighted - Puea was the name of an idol deity - and if the weather was fair and it did not rain that night, the night of Puea, it was an omen of prosperity to the land. In that case, on the following morning, on the day Lono (28th), a canoe was sent out on a fishing excursion; and on its return, all the male chiefs and the men ate of the fresh fish that had been caught; but not the women. On that day also the bandages, which had covered the eyes of the high-priest were removed.

On the morning of Mauli (29th) the people again went after pala-fern, and at night the fire of Puea was again lighted. On the morning of the next day, Muku, the last of the month, the fishing canoe again put to sea. The same thing was repeated on the following day, Hilo, which was the first of the month, the new month Makalii, and that night the fires of Puea were again lighted, and the following morning the fishing-canoe again put to sea.

The same programme was followed the next day, and the next, and the day following that, until the four Ku (3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th), as well as the four days of the Ole-tabu, (7th, 8th, 9th, and 10th) were accomplished. On each of these days a fresh supply of pala-fern was gathered; each night the signal fires of Puea burned, and on each following morning the fishing canoe put forth to get a fresh supply of fish. This was also done on Huna (11th); and that day the queen and all the women ate of the fresh fish from the ocean. This observance was termed Kala-hua.21

On the morning of Mohalu (12th), the tabu set in again and continued through the days Hua, Akua, and Hoku, during which period no canoe was allowed to go fishing. On the following day, Mahealani, the Makahiki god returned from making the circuit of the island.

On that day the king for the first time again bathed in the ocean. It was on the same evening that the Makahiki god was brought back to the luakini.22

That same evening the king sailed forth in a canoe accompanied by his retinue and his soldiery, to meet the Makahiki god on his return from his tour, a ceremony which was called ka-lii.23

When the king came to where the Makahiki god was, behold there was a large body of men, with spears in their hands, drawn up at the landing as if to oppose him.

The king was accompanied on this expedition by one of his own men who was an expert in warding off spears. This man went forward in advance of the king. And as the king jumped ashore, one of the men forming the company about the Makahiki god came on the run to meet him, holding in his hands two spears bound at their points with white cloth called oloa.

One of these he hurled at the king and it was warded off by the one who went in advance. The second spear was not thrown, the man merely touched the king with it.

That same afternoon they had a sham-fight with spears, which was termed a Kane-kupua. After that the king went into the temple of Waiea24 to pay his respects to the Makahiki god Lono-makua, as well as to the akua-poko.

When the king came into the presence of these gods he offered a pig as a sacrifice. It was put upon the lele before the idols, and then the king went home for the night.

The next day was kulu (17th), and that evening a temporary booth, called a hale kamala, of lama, wood, was put up for Kahoalii25 directly in front of the temple, Waiea, and in it Kahoalii spent the night. This hut was called the net-house of Kahoalii (ka hale koko o Kahoalii),

That same night a very fat pig, called a puaa hea, was put into the oven along with preparations of cocoanut, called kulolo, and at daybreak, when the process of cooking was complete, all the people feasted on it; and if any portion was left over, it was carefully disposed of. This was on the morning of Laau-kukahi, and that same day the following work was done:

Namely, the entire dismantling of the Makahiki idols, leaving nothing but the bare images; after which they and all their appurtenances were bundled up and deposited in the luakini. The men who carried the idols were then fed, and the kahunas closed the services of the day with prayer.

A net with large meshes was then made, which, being lifted by four men supporting it at the four corners, was filled with all kinds of food, such as taro, potatoes, bread-fruit, bananas, cocoanuts, and pork, after which the priests stood forth to pray.

When the kahuna in his prayer uttered the word hapai (lift), the men lifted the net and shook it back and forth, to make the food drop through the meshes, such being the purpose of the ceremony. This was called the net of Maoloha.26 If the food did not drop from the net, the kahuna declared there would be a famine in the land; but if it all fell out he predicted that the season would be fruitful.

A structure of basket-work, called the waa-auhau27 was then made, which was said to represent the canoe in which Lono returned to Tahiti.

The same day also a canoe of unpainted wood, called a waa kea, was put to sea and coursed back and forth. After that the restrictions of the Makahiki were entirely removed and every one engaged in fishing, farming, or any other work.

On that same day orders were given that the timber for a new heiau, called a kukoae28 should be collected with all haste. The next day was Laau-kulua, and on the evening of the following day, Laau-pau, the 20th, the king announced the tabu of Kalo-ka-maka-maka, which was the name of the prayer or service. This pule, or service, continued until Kaloa-kulua, the 25th, when it came to an end, was noa.

On the morning of Kaloa-pau, 26th, the king performed the ceremony of purification. He had built for himself a little booth, called a hale-puu-puu-one29 performing its ceremony of consecration and ending it that day; then another small house, or booth, called oeoe30, then a booth covered with pohue vine; then one called palima31; and last of all a heiau called kukoa'e-ahuwai.32 Each of these was consecrated with prayer and declared noa on that same day by the king, in order to purify himself from the pleasures, in which he had indulged, before he resumed his religious observances.

On the morning of the next day, which was Kane (27th), the king declared the tabu of the heiau he had built, which was of the kind called kukoa'e, because it was the place in which he was to cleanse himself from all impurities, haumia, and in which he was to eat pork. This heiau was accordingly called a kukoa'e in which to eat pork, because in it the king resumed the use of that meat.

During the tabu period of Ku, in the month of Kaelo, people went their own ways and did as they pleased; prayers were not offered. During the tabu period of Hua in Kaelo the people again had to make a hookupu for the king. It was but a small levy, however, and was called the heap of Kuapola. (Ka pu'u o Kuapola.)

It was in this same tabu-period that Kahoalii33 plucked out and ate an eye from the fish aku34 together with an eye from the body of the man who had been sacrificed. After this the tabu was removed from the aku and it might be eaten; then the opelu in turn became tabu, and could be eaten only on pain of death.

During this same tabu or pule the king and the high priest slept in their own houses. (They had been sleeping in the heiau.) On the last day of the tabu-period the king and kahuna-nui, accompanied by the man who beat the drum, went and regaled themselves on pork. The service at this time was performed by a distinct set of priests. When these services were over the period of Makahiki and its observances were ended, this being its fourth month. Now began the new year.35

In the tabu-period of Ku of the month Kaulua, the king, chiefs, and all the people took up again their ordinary religious observances, because religion, i.e. haipule, has from the very beginning of Hawaiian history been a matter of the greatest concern.

In the tabu-period Ku, of the month Kaulua, or it might be of the month Nana, the king would make a heiau of the kind called a heiau-loulu, or it might be, he would put up one of the kind called a ma'o. He might prefer an ordinary luakini; or, he might see fit to order the building of a temple to propitiate the gods for abundant harvests, that would be a luakini houululu ai; or he might order the building of a war-temple, a luakini kaua.37 It was a matter which lay with the king.

It was a great undertaking for a king to build a heiau of the sort called a luakini, to be accomplished only with fatigue and redness of the eyes from long and wearisome prayers and ceremonies on his part.

There were two rituals which the king in his eminent station used in the worship of the gods; one was the ritual of Ku, the other that of Lono. The Ku-ritual was very strict (oolea), the service most arduous (ikaika). The priests of this rite were distinct from others and outranked them. They were called priests of the order of Ku, because Ku was the highest god whom the king worshipped in following their ritual. They were also called priests of the order of Kanalu, because that was the name of their first priestly ancestor. These two names were their titles of highest distinction.

The Lono-ritual was milder, the service more comfortable. Its priests were, however, of a separate order and of an inferior grade. They were said to be of the order of Lono (moo-Lono), because Lono was the chief object of the king's worship when he followed the ritual. The priests of this ritual were also said to be of the order of Paliku.

If the king was minded to worship after the rite of Ku, the heiau he would build would be a luakini. The timbers of the house would be of ohia. the thatch of loulu-palm or of tiki grass. The fence about the place would be of ohia with the bark peeled off. The lananu'u-mamao1 had to be made of ohia timber so heavy that it must be hauled down from the mountains. The same heavy ohia timber was used in the making of the idols for the heiau.

The tabu of the place continued for ten days and then was noa; but it might be prolonged to such an extent as to require a resting spell, hoomahanahana;2 and it might be fourteen days before it came to an end. It all depended on whether the aha3 was obtained. If the aha was not found the heiau would not soon be declared noa. In case the men took a resting spell, a dispensation was granted and a service of prayer was offered to relax the tabu, after which the heiau stood open.

The body of priests engaged in the work stripped down the leaves from a banana-stalk as a sign that the tabu was relaxed: and when the Ku-tabu of the next month came round, the tabu of the heiau was again imposed. Thus it was then that if the aha was procured the services of prayer came to an end; otherwise people and chiefs continued indefinitely under tabu and were not allowed to come to their women-folk.

The tabu might thus continue in force many months, possibly for years, if the aha were not found. It is said that Umi was at work ten years on his heiau before the aha was found, and only then did they again embrace their wives. This was the manner of building a heiau-luakini from the very earliest times; it was noa only when the aha had been found. It was indeed an arduous task to make a luakini; a human sacrifice was necessary, and it must be an adult, a law-breaker ( lawe-hala ) .