Hawaiian

Antiquities (Mo`ōlelo Hawai`i)

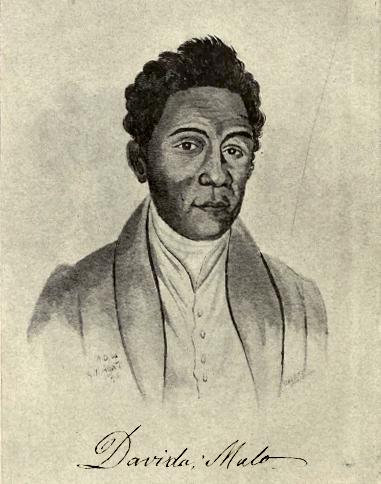

By David Malo,

Honolulu Hawaiian Gazette Co., Ltd.

Translated

from the Hawaiian

by Dr. N. B. Emerson 1898

|

Introduction

The second edition of the Mo`ōlelo Hawai`i, which appeared in 1858, was compiled by Rev. J. F. Pogue, who added to the first edition extensive extracts from the manuscript of the present work, which was then the property of Rev. Lorrin Andrews, for whom it had been written, probably about 1840. David Malo's Life of Kamehameha I, which is mentioned by Dr. Emerson in his life of Malo, must have been written before that time, as it passed through the hands of Rev. W. Richards and of Nahienaena, who died December 30, 1836. Its disappearance is much to be deplored.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER 1

General Remarks On Hawaiian History

The traditions about the Hawaiian Islands handed down from remote antiquity are not entirely definite; there is much obscurity as to the facts, and the traditions themselves are not clear. Some of the matters reported are clear and intelligible, but the larger part are vague.

The reason for this obscurity and vagueness is that the ancients were not possessed of the art of letters, and thus were: unable to record the events they witnessed, the traditions handed! down to them from their forefathers and the names of the lands in which their ancestors were born. They do, however, mention by name the lands in which they sojourned, but not the towns and the rivers. Because of the lack of a record of these matters it is impossible at the present time to make them out clearly.

The ancients left no records of the lands of their birth, of what people drove them out, who were their guides and leaders, of the canoes that transported them, what lands they visited in their wanderings, and what gods they worshipped. Certain oral traditions do, however, give us the names of the idols of our ancestors.

Memory was the only means possessed by our ancestors of preserving historical knowledge; it served them in place of books and chronicles.

No doubt this fact explains the vagueness and uncertainty of the more ancient traditions, of which some are handed down correctly, but the great mass incorrectly. It is likely there is greater accuracy and less error in the traditions of a later date.

Faults of memory in part explain the contradictions that appear in the ancient traditions, for we know by experience that "the heart is the most deceitful of all things."

When traditions are carried in the memory it leads to contradictory versions. One set think the way they heard the story is the true version; another set think theirs is the truth; a third set very likely purposely falsify. Thus it comes to pass that the traditions are split up and made worthless.

The same cause no doubt produced contradictions in the genealogies (moo-ku-auhau). The initial ancestor in one genealogy differed from that in another, the advocate of each genealogy claiming his own version to be the correct one. This cause also operated in the same way in producing contradictions of the historical traditions; one party received the tradition in one way, another party received it in another way.

In regard to the worship of the gods, different people had different gods, and both the worship and the articles tabued differed the one from the other. Each man did what seemed to him right, thus causing disagreement and confusion.

The genealogies have many separate lines, each one different from the other, but running into each other. Some of the genealogies begin with Kumu-lipo 1 as the initial point; others with Pali-ku 2; others with Lolo 3; still others with Pu-anue 4; and others with Ka-po-hihi 5. This is not like the genealogy from Adam, which is one unbroken line without any stems.

There are, however, three genealogies that are greatly thought of as indicating the Hawaiian people as well as their kings, These are Kumn-lipo, Pali-ku, and Lolo. And it would seem as if the Tahitians and Nuuhivans had perhaps the same origin, for their genealogies agree with these.

Formation Of The Land (Cosmogony)

It is very surprising to hear how contradictory are the accounts given by the ancients of the origin of the land here in Hawaii.

It is in their genealogies (moo-ku-auhau) that we shall see the disagreement of their ideas in this regard.

In the moo-ku-auhau, or genealogy named Pu-anue, it is said that the earth and the heavens were begotten (hanau maoli mai).

It was Kumukumu-ke-kaa who gave birth to them, her husband being Paia-a-ka-lani. Another genealogy declares that Ka-mai-eli gave birth to the foundations of the earth (mole o ka honua), the father being Kumu-honua.

In the genealogy of Wakea it is said that Papa gave birth to these Islands. Another account has it that this group of islands were not begotten, but really made by the hands of Wakea himself.

In the genealogy called Kumu-lipo it is said that the land grew up of itself, not that it was begotten, nor that it was made by hand.

In these days certain learned men have searched into and studied up the origin of the Hawaiian Islands, but whether their views are correct no one can say, because they are but speculations.

These scientists from other lands have advanced a theory and expressed the' opinion that there was probably no land here in ancient times, only ocean; and they think that the Islands rose up out of the ocean as a result of volcanic action.

Their reasons for this opinion are that certain islands are known which have risen up out of the ocean and which present features similar to Hawaii nei. Again a sure indication is that the soil of these Islands is wholly volcanic. All the islands of this ocean are volcanic, and the rocks, unlike those of the continents, have been melted in fire. Such are their speculations and their reasoning.

The rocks of this country are entirely of volcanic origin. Most of the volcanoes are now extinct, but in past ages there were volcanoes on Maui and on all the Islands. Back to Contents

The Origin Of The Primitive Inhabitants Of Hawaii Nei

In Hawaiian ancestral genealogies it is said that the earliest inhabitants of these Islands were the progenitors of all the Hawaiian people.

In the genealogy called Kumu-lipo it is said that the first human being was a woman named La'ila'i and that her ancestors and parents were of the night (he po wale no), that she was the progenitor of the (Hawaiian) race.

The husband of this La'ila'i was named Ke-alii-wahi-lani (the king who opens heaven); but it is not stated who were the parents of Ke-alii-wahi-lani, only that he was from the heavens; that he looked down and beheld a beautiful woman, La'ila'i, dwelling in Lalawaia; that he came down and took her to wife, and from the union of these two was begotten one of the ancestors of this race. And after La'ila'i and her company it is again stated in the genealogy called Lolo that the first native Hawaiian (kanaka) was a man named Kahiko. His ancestry and parentage are given, but without defining their character; it is only said he was a human being (kanaka).

Kupulanakehau was the name of Kahiko's wife; they begot Lihauula and Wakea. Wakea had a wife named Haumea, who was the same as Papa. In the genealogy called Pali-ku it is said that the parents and ancestors of Haumea the wife of Wakea were pali (precipices). With her the race of men was definitely established.

These are the only people spoken of in the Hawaiian genealogies; they are therefore presumably the earliest progenitors of the Hawaiian race. It is not stated that they were born here in Hawaii. Probably all of these persons named were born in foreign lands, while their genealogies were preserved here in Hawaii.

One reason for thinking so is that the countries where these people lived are given by name and no places in Hawaii are called by the same names. La'ila'i and Ke-alii-wahi-lani lived in Laiowaia; Kahiko and Kupu-lana-ke-hau lived in Kamawae-lualani; Wakea and Papa lived in Lolo-i-mehani.

There is another fact mentioned in the genealogies, to-wit: that when Wakea and Papa were divorced from each other, Papa went away and dwelt in Nuu-meha-lani. There is no place here in Hawaii called Nuu-meha-lani. The probability is that these names belong to some foreign country. Back to Contents

CHAPTER 4

Of The Generations Descended From Wakea

It is said that from Wakea down to the death of Haumea there were six generations, and that these generations all lived in Lolo-i-mehani; but it is not stated that they lived in any other place; nor is it stated that they came here to Hawaii to live.

Following these six generations of men came nineteen generations, one of which, it is supposed, migrated hither and lived here in Hawaii, because it is stated that a man named Kapawa, of the twentieth generation, was born in Kukaniloko, in Waialua, on Oahu.

It is clearly established that from Kapawa down to the present time generations of men continued to be born here in Hawaii; but it is not stated that people came to this country from Lolo-i-mehani; nor is it stated who they were that first came and settled here in Hawaii; nor that they came in canoes, waa; nor at what time they arrived here in Hawaii.

It is thought that this people came from lands near Tahiti and from Tahiti itself, because the ancient Hawaiians at an early date mentioned the name of Tahiti in their meles, prayers, and legends.

I will mention some of the geographical names given in meles: Kahiki-honua-kele1 Anana-i-malu,2 Holani3 Hawa-ii, Nuu-hiwa; in legends or kaaos, Upolu, Wawau, Kukapuaiku, Kuaihelani; in prayers, Uliuli, Melemele, Polapola, Haehae, Maokuululu, Hanakalauai.

Perhaps these names belong to lands in Tahiti. Where, indeed, are they? Very likely our ancestors sojourned in these lands before they came hither to Hawaii.

Perhaps because of their affection for Tahiti and Hawaii they applied the name Kahiki nui to a district of Maui, and named this group (pae-aina) Hawaii. If not that, possibly the names of the first men to settle on these shores were Hawaii, Maui, Oahu, Kauai, and at their death the islands were called by their names.

The following is one way by which knowledge regarding Tahiti actually did reach these shores: We are informed (by historical tradition) that two men named Paao and Makua-kaumana, with a company of others, voyaged hither, observing the stars as a compass; and that Paao remained in Kohala, while Makua-kaumana returned to Tahiti.

Paao arrived at Hawaii during the reign of Lono-ka-wai4 the king of Hawaii. He (Lono-ka-wai) was the sixteenth in that line of kings, succeeding Kapawa.

Paao continued to live in Kohala until the kings of Hawaii became degraded and corrupted (hewa); then he sailed away to Tahiti to fetch a king from thence. Pili5 (Kaaiea) was that king and he became one in Hawaii's line of kings (papa alii).

It is thought that Kapua in Kona was the point of Paao's departure, whence he sailed away in his canoe; but it is not stated what kind of a canoe it was. In his voyage to Hawaii, Pili was accompanied by Paao and Makua-kaumana and others. The canoes (probably two coupled together as a double canoe) were named Ka-nalo-a-mu-ia. We have no information as to whether these canoes were of the kind called Pahi.6

Tradition has it that on his voyage to this country Pili was accompanied by two schools of fish, one of opelu and another of aku and when the wind kicked up a sea, the aku would frisk and the opelu would assemble together, as a result of which the ocean would entirely calm down. In this way Pili and his company were enabled to voyage till they reached Hawaii. On this account the opelu and the aku were subject to a tabu in ancient times. After his arrival at Hawaii, Pili was established as king over the land, and his name was one of the ancestors in Hawaii's line of kings.

There is also a tradition of a man named Moikeha, who came to this country from Tahiti in the reign of Kalapana, king of Hawaii.

After his arrival Moikeha went to Kauai to live and took to wife a woman of that island named Hinauulua, by whom he had a son, to whom he gave the name Kila.

When Kila was grown up he in turn sailed on an expedition to Tahiti, taking his departure, it is said, from the western point of Kahoolawe, for which reason that cape is to this day called Ke-ala-i-kahiki (the route to Tahiti).

Kila arrived in safety at Tahiti and on his return to these shores brought back with him Laa-mai-kahiki."7 On the arrival of Laa was introduced the use of the kaekeeke8 drum. An impetus was given at the same time to the use of sinnet in canoe lashing (aha hoa waa), together with improvements in the plaited ornamental knots or lashings, called lanalana.9 The names I have mentioned are to be numbered among the ancestors of Hawaiian kings and people, and such was the knowledge and information obtained from Tahiti in ancient times, and by such means as I have described was it received.

The Hawaiians are thought to be of one race with the people of Tahiti and the Islands adjacent to it. The reason for this belief is that the people closely resemble each other in their physical features, language, genealogies, traditions (and legends), as well as in (the names of) their deities. It is thought that very likely they came to Hawaii in small detachments.

It seems probable that this was the case from the fact that in Tahiti they have large canoes called pahi; and it seems likely that its possession enabled them to make their long voyages to Hawaii. The ancients are said to have been skilled also in observing the stars, which served them as a mariner's compass in directing their course.

The very earliest and most primitive canoes of the Hawaiians were not termed pahi, nor yet were they called moku (ships); the ancients called them waa.

It has been said, however, that this race of people came from the Iewa10 the firmament, the atmosphere; from the windward or back of the island (kua o ka moku).

The meaning of these expressions is that they came from a foreign land, that is the region of air, and the front of that land is at the back of these islands.

Perhaps this was a people forced to flee hither by war, or driven in this direction by bad winds and storms. Perhaps by the expression lewa, or regions of air, Asia is referred to; perhaps this expression refers to islands they visited on their way hither; so that on their arrival they declared they came from the back (the windward) of these islands.

Perhaps this race of people was derived from the Israelites, because we know that certain customs of the Israelites were practiced here in Hawaii.

Circumcision, places of refuge, tabus (and ceremonies of purification) relating to dead bodies and their burial, tabus and restrictions pertaining to a flowing woman, and the tabu that secluded a woman as defiled during the seven days after childbirth all these customs were formerly practiced by the people of Hawaii.

Perhaps these people are those spoken of in the Word of God as "the lost sheep of the House of Israel," because on inspection we clearly see that the people of Asia are just like the inhabitants of these islands, of Tahiti and the lands adjacent.

CHAPTER 5 Names Given To Directions Or The Points Of The Compass The ancients named directions or the points of the compass from the course of the sun. The point where the sun rose was called kukulu1 hikina. and where the sun set was called kukulu komohana. If a man faces towards the sunset his left hand will point to the south, kukulu hema, his right to the north kukulu akau. These names apply only to the heavens (lani), not2 to the land or island (mokupuni) . These points were named differently when regard was had to the borders or coasts (aoao) of an island. If a man lived on the western side of an island the direction of sun-rising was termed uka, and the direction of sun-setting kai, so termed because he had to ascend a height in going inland, uka, and descend to a lower level in going to the sea, kai. Again, north, kiikulu akau, is also spoken of as luna, or i-luna (up), and south is spoken of as lalo ( down), the reason being that that quarter of the heavens, north, when the (prevailing) wind blows is spoken of as up, and the southern quarter, towards which it blows, is spoken of as down. As to the heavens, they are called the solid above, ka paa iluna,3 the parts attached to the earth are termed ka paa ilalo, the solid below; the space between the heavens and the earth is sometimes termed ka lewa, the space in which things hang or swing. Another name is ka hookui,4 the point of juncture, and another still is ka halawai, i.e. the meeting. To a man living on the coast of an island the names applied to the points of compass, or direction, varied according to the side of the island on which he lived. If he lived on the eastern side of the island he spoke of the west as uka, the east as kai. This was when he lived on the side looking east. For the same reason he would term South akau because his right hand pointed in that direction, and north he would term hema5, i.e. left, because his left hand pointed that way. In the same way by one living on the southern exposure of an island, facing squarely to the south, the east would be called hema, left, akau, the west. So also to one living on the northern face of an island the names applied to the points of compass are correspondingly all changed about. Here is another style of naming the east: from the coming of the sun it is called the sun arrived, ka-la-hiki, and the place of the sun's setting is called ka-la-kau, the sun lodged. Accordingly they had the expression mai ka la hiki a ka la kau, from the sun arrived to the sun lodged; or they said mai kela paa a keia paa,6 from that solid to this solid. These terms applied only to the borders, or coasts, of an island, not to the points of the heavens, for it was a saying "O Hawaii ka la hiki, o Kauai ka la kau," Hawaii is the sun arrived, Kauai is the sun lodged. The north of the islands was spoken of as "that solid," kela paa, and the south of the group as "this solid," keia paa. It was in this sense they used the expression "from that firmament or solid to this firmament." According to another way of speaking of directions (kukulu), the circle of the horizon 'encompassing the earth at the borders of the ocean, where the sea meets the base of the heavens, kumu lani. this circle was termed kukulu o ka honua, the compass of the earth. The border of the sky where it meets the ocean-horizon is termed the kukulu-o-ka-lani, the walls of heaven. The circle or zone of the earth's surface, whether sea or land, which the eye traverses in looking to the horizon is called Kahikimoe. The circle of the sky which bends upwards from the horizon is Kahiki-ku; above Kahiki-ku is a zone called Kahiki-ke-papa-nuu; and above that is Kahiki-ke-papa-lani; and directly over head is Kahiki-kapui-holani-ke-kuina. The space directly beneath the heavens is called lewa-lani; beneath that, where the birds fly, is called lewa-nuu; beneath that is lewa-lani-lewa; and beneath that, the space in which a man's body would swing were he suspended from a tree, with his feet clear of the earth, was termed lewa-hoomakua. By such a terminology as this did the ancients designate direction.

Terms Used To Designate Space Above And Below The ancients applied the following names to the divisions of space above us. The space immediately above one's head when standing erect is spoken of as luna-ae; above that luna-aku; above that luna-loa-aku; above that luna-lilo-aku; above that luna-lilo-loa; and above that, in the firmament where the clouds float, is luna-o-ke-ao; and above that were three divisions called respectively ke-ao-ulu, ka-lani-uli and ka-lani-paa, the solid heavens. Ka-lani-paa is that region in the heavens which seems so remote when one looks up into the sky. The ancients imagined that in it was situated the track along which the sun travelled until it set beneath the ocean, then turning back in its course below till it climbed up again at the east. The orbits of the moon and the stars also were thought to be in the same region with that of the sun, but the earth was supposed to be solid and motionless. The clouds; which are objects of importance in the sky, were named from their color or appearance. A black cloud was termed eleele, if blue-black it was called uliuli, if glossy black hiwahiwa, or polo-hiwa. Another name for such a cloud was panopano. A white cloud was called keokeo, or kea. If a cloud had a greenish tinge it was termed maomao, if a yellowish tinge lena. A red cloud was termed ao ula, or kiawe-ula or onohi-ula, red eye-ball. If a cloud hung low in the sky it was termed hoo-leivalewa, or the term hoo-pehu-pehu, swollen, was applied to it. A sheltering cloud was called hoo-malu-malu, a thick black cloud hoo-koko-lii, a threatening cloud hoo-weli-weli. Clouds were named according to their character. If a cloud was narrow and long, hanging low in the horizon, it was termed opua, a bunch or cluster. There were many kinds of opua each being named according to its appearance. If the leaves of the opua pointed downwards it might indicate wind or storm, but if the .leaves pointed upwards, calm weather. If the cloud was yellowish and hung low in the horizon it was called newe-newe, plump, and was a sign of very calm weather. If the sky in the western horizon was blue-black, uli-uli, at sunset it was said to be pa-uli and was regarded as prognosticating a high surf, kai-koo. If there was an opening in the cloud, like the jaw of the a'u, (sword fish), it was called ena and was considered a sign of rain. When the clouds in the eastern heavens were red in patches before sunrise it was called kahea (a call) and was a sign of rain. If the cloud lay smooth over the mountains in the morning it was termed papala and foretokened rain. It was also a sign of rain: when the mountains were shut in with blue-black clouds, and this appearance was termed pala-moa. There were many other signs that betokened rain. If the sky was entirely overcast, with almost no wind, it was said to be poi-pu (shut up), or hoo-ha-ha, or hoo-lu-luhi; and if the wind started up the expression hoo-ka-kaa, a rolling together, was used. If the sky was shut in with thick, heavy clouds it was termed hakuma, and if the clouds that covered the sky were exceedingly black it was thought that Ku-lani-ha-koi was in them, the place whence came thunder, lightning, wind, rain,, violent storms. When it rained, if it was with wind, thunder, lightning and perhaps a rainbow, the rain-storm would probably not continue long. But if the rain was unaccompanied by wind it would probably be a prolonged storm. When the western heavens are red at sunset the appearance is termed aka-ula (red shadow or glow) and is looked upon as a sign that the rain will clear up. When the stars fade away and disappear it is ao, daylight, and when the sun rises day has come, we call it la; and when the sun becomes warm, morning is past. When the sun is directly overhead it is awakea, noon; and when the sun inclines to the west in the afternoon the expression is ua aui ka la. After that comes evening, called ahi-ahi (ahi is fire) and then sunset, na poo ka la, and then comes po, the night, and the stars shine out. Midnight, the period when men are wrapped in sleep, is called au-moe, (the tide of sleep). When the milky way passes the meridian and inclines to the west, people say ua huli ka i'a, the fish has turned, Ua ala-ula mai o kua, ua moku ka pawa o ke ao; a keokeo mauka, a wehe ke ala-ula, a pua-lena, a ao loa, i.e. "There comes a glimmer of color in the mountains, the curtains of night are parted; the mountains light up; day breaks; the east blooms with yellow; it is broad daylight." Rain is an important phenomenon from above; it lowers the temperature. The ancients thought that smoke from below turned into clouds and produced rain. Some rain-storms have their origin at a distance. The kona was a storm of rain with wind from the south, a heavy rain. The hoolua-storm was likewise attended with heavy rain, but with wind from the north. The naulu, accompanied with rain, is violent but of short duration. The rain called awa is confined to the mountains, while that called kualau occurs at sea. There is also a variety of rain termed a-oku. A water-spout was termed wai-pui-lani. There were many names used by the ancients to designate appropriately the varieties of rain peculiar to each part of the island coast; the people of each region naming the varieties of rain as they deemed fitting. A protracted rain-storm was termed na-loa, one of short duration ua poko, a cold rain ua hea. The ancients also had names for the different winds.1 Wind always produced a coolness in the air. There was the kona, a wind from the south, of great violence and of wide extent. It affected all sides of an island, east, west, north and south, and continued for many days. It was felt as a gentle wind on the Koolau, the north-eastern or trade-wind side of an island, but violent and tempestuous on the southern coast, or the front of the islands, (ke alo o na mokupuni). The kona wind often brings rain, though sometimes it is rainless. There are many different names applied to this wind. The kona-ku is accompanied with an abundance of rain; but the kona-mae, the withering kona, is a cold wind. The kona-lani brings slight showers; the kona-hea is a cold storm; and the kona hili-maia the banana-thrashing kona blows directly from the mountains. The hoolua, a wind that blows from the north, sometimes brings rain and sometimes is rainless. The hau is a wind from the mountains, and they are thought to be the cause of it, because this wind invariably blows from the mountains outwards towards the circumference of the island.2 There is a wind which blows from the sea, and is thought to be the current of the land-breeze returning again to the mountains. This wind blows only on the leeward exposure or front (alo) of an island. In some parts this wind is named eka (a name used in Kona, Hawaii), in others aa, (a name used at Lahaina and elsewhere), in others kai-a-ulu, and in others still inu-wai.3 There was a great variety of names applied to the winds by the ancients as the people saw fit to name them in different places. The place beneath where we stand is called lalo; below that is lalo-o-ka-lepo (under ground); still below that is lalo-liloa (the full form of the expression would be lalo-lilo-loa); the region still further below the one last mentioned was called lalo-ka-papa ku. A place in the ocean was said to be maloko o ke kai, that is where fish always live. Where the ocean looks black it is very deep and there live the great fish. The birds make their home in the air; some birds live in the mountains.

Natural and Artificial Divisions of the Land The ancients gave names to the natural features of the land according to their ideas of fitness. Two names were used to indicate an island; one was moku, another was aina. As separated from other islands by the sea, the term moku (cut off) was applied to it; as the stable dwelling place of men, it was called aina, land, (place of food). When many islands were grouped together, as in Hawaii nei, they were called pae-moku or pae-aina; if but one moku or aina. If one (easily) voyaged in a canoe from one island to another, the island from which he went and that from which he sailed were termed moku kele i ka waa, an island to be reached by a canoe, because they were both to be reached by voyaging in a canoe. Each of the larger divisions of this group, like Hawaii, Maui and the others, is called a moku-puni (moku, cut off, and puni, surrounded). An island is divided up into districts called apana, pieces, or moku-o-loko, interior divisions, for instance Kona on Hawaii, or Hana on Maui, and so with the other islands. These districts are subdivided into other sections which are termed sometimes okana and sometimes kalana. A further subdivision within the okana is the poko. By still further subdivision of these sections was obtained a tract of land called the ahu-puaa, and the ahu-puaa was in turn divided up into pieces called ili-aina. The ili-aina were subdivided into pieces called moo-aina, and these into smaller pieces called pauku-aina (joints of land), and the panku-aina into patches or farms called kihapai. Below these subdivisions came the koele1, the haku-one2 and the kuakua3. According to another classification of the features of an island the mountains in its centre are called kua-hiwi, back-bone, and the name kua-lono4 is applied to the peaks or ridges which form their summits. The rounded abysses beneath are (extinct) craters, kua pele. Below the kua-hiwi comes a belt adjoining the rounded swell of the mountain called kua-mauna or mauna, the mountainside. The belt below the kua-mauna, in which small trees grow, is called kua-hea, and the belt below the kua-hea, where the larger sized forest-trees grow is called wao5, or wao-nahele, or wao-eiwa. The belt below the woo-eiwa was the one in which the monarch s of the forest grew, and was called wao-maukele, and the belt below that, in which again trees of smaller size grew was called wao-akua6 and below the wao-akua comes the belt called wao-kanaka or ma'u. Here grows the ama'au fern and here men cultivate the land. Below the ma'u comes the belt called apaa (probably because the region is likely to be hard, baked, sterile), and below this comes a belt called ilima7 and below the ilima comes a belt called pahee, slippery,8 and below that comes a belt called kula (plain, open country) near to the habitations of men, and still below this comes the belt bordering the ocean called kahakai, the mark of the ocean (kaha, mark, and kai, sea.) There are also other names to designate the features of the land: The hills that stand here and there on the island are called puu, a lump or protuberance; if the hills stand in line they are designated as lalani puu or pae puu; if they form a cluster of hills they are designated kini-kini puu or olowalu puu. A place of less eminence was called an ahua; or if it was lower still an ohu, or if of still less eminence (a plateau) it was termed kahua.9 A narrow strip of high land, that is a ridge, was called a lapa or a kua-lapa, and a region abounding in ridges was called olapa-lapa. A long depression in the land, a valley, was called a kahu-wai; it was also called awawa or owawa. Those places where the land rises up abrupt and steep like the side of a house are named pali10; if less decided precipitous they are spoken of as opalipali. A place where runs a long and narrow stretch of beaten earth, a road namely, is termed ala-nui; another name is kua-moo (lizard-back). When a road passed around the circumference of the island it was called the ala-loa. A place where the road climbed an ascent was termed pii'na; another name was hoopii'na; another name still was koo-ku, and still another name was auku. Where a road passed down a descent it was termed iho'na, or alu, or ka-olo (olo-kaa, to roll down hill), or ka-lua or hooiho'na. The terraces or stopping places on a (steep) road where people are wont to halt and rest are called oi-o-ina. A (natural) water-course or a stream of water was called a kahawai (scratch of water); its source or head was called kumu-wai; its outlet or mouth was called nuku-wai. An (artificial) ditch or stream of water for irrigating land is called au wai. When a stream mingles with sea water (as in the slack water of a creek) it is termed a mui-wai11. A body of water enclosed by land, i.e. a lake or pond, is called a loko.

Concerning the Rocks The ancients applied to various hard, or mineral, substances the term pohaku rocks or stones. A rocky cliff was called a pali-pohaku; a smaller boulder or mass of rock would be termed pohaku uuku iho. The term a-a was applied to stones of a somewhat smaller size. Below them came iliili or pebbles. When of still smaller size, such as gravel or sand, the name one was applied, and if still more finely comminuted it was called lepo, dirt. A great many names were used to distinguish the different kinds of rocks. In the mountains were found some very hard rocks which probably had never been melted by the volcanic fires of Pele. Axes were fashioned from some of these rocks, of which one kind was named uli-uii, another ehu-ehu. There were many varieties. The stones used for axes were of the following varieties: ke-i, ke-pue, ala-mea, kai-alii, humu-ula, pi-wai, awa-lii, lau-kea, mauna. All of these are very hard, superior to other stones in this respect, and not vesiculated like the stone called ala. The stones used in making lu-hee for squid-fishing are peculiar and were of many distinct vareties. Their names are hiena, ma-heu, hau, pa-pa, lae-koloa, lei-ole, ha-pou, kawau-puu, ma-ili, au, nani-nui, ma-ki-ki, pa-pohaku, kaua-ula, wai-anuu-kole, hono-ke-a-a, kupa-oa, poli-poli, ho-one, no-hu, lu-au, wai-mano, hule-ia, maka-wela. The stones used for maikas were the ma-ka, hiu-pa iki-makua, kumu-one,1 ma-ki-ki, kumu-mao-mao, ka-lama-ula, and paa-kea. 2 Volcanic pa-hoe-hoe is a class of rocks that have been melted by the fires of Pele. Ele-ku and a-na pumice, are very light and porous rocks. Another kind of stone is the a-la3 and the pa-ea. The following kinds of stone were used in smoothing and polishing canoes and wooden dishes, coral stones (puna), a vesiculated stone called o-ahi, o-la-i or pumice, po-huehue, ka-wae-wae, o-i-o, and a-na. The kinds of stone used in making poi-pounders were a-la, lua-u, kohe-nalo, the white sand-stone called kumu-one, and the coral-stone called koa. There is also a stone that is cast down from heaven by lightning. No doubt there are many other stones that have failed of mention.

Plants and Trees The ancients gave the name laau to every plant that grows in the earth of which there are a great many kinds (ano). The name laau was, however, applied par eminence to large trees; plants of a smaller growth were termed laa-lau; the term nahele (or nahele-hele) was used to indicate such small growths as brush, shrubs, and chapparal. Plants of a still smaller growth were termed weu-weu; grasses were termed mauu. The pupu-keawe1 (same as pu-keawe), another name for which is mai-eli, is a sort of brush, nahele, that grows on the mountain sides. It was used in in cremating the body of any one who had made himself an outlaw beyond the protection of the tabu. Further down the mountain grows the ohia (same as the Iehua), a large tree. In it the bird-catchers practiced their art of bird-snaring. It was much used for making idols, also hewn into posts and rafters for houses, used in making the enclosures about temples, and for fuel, also from it were made the sticks to couple together the double canoes, besides which it had many other uses. The koa2 was the tree that grew to be of the largest size in all the islands. It was made into canoes, surf-boards, paddles, spears, and (in modern times) into boards and shingles for houses. The koa is a tree of many uses. It has a seed and its leaf is crescent-shaped. The ahakea3 is a tree of smaller size than the koa. It is valued in canoe making, the fabrication of poi-boards, paddles, and for many other uses. The kawau was a tree useful for canoe timber and for tapa logs. The manono and aiea were trees that also furnished canoe timber. The kopiko was a tree that furnished wood that was useful for making tapa-logs (kua kuku kapa) and that also furnished good fuel. The kolea was a tree the wood of which was used in making tapa-logs and as timber for houses. Its charcoal was used in making black dye for tapa. The naia was a tree the wood of which was used in canoe-making.4 The sandal-wood, ili-ahi, has a fragrant wood which is of great commercial value at the present time. The naio also is a sweet-scented wood and of great hardness. The pua is a hard wood. The kauila is a hard wood, excellent for spears, tapa-beaters and a variety of other similar purposes.5

The mamane. and uhi-uhi were firm woods used in making the runners for holua-sleds and spades, o-o, used by the farmers. The alani was one of the woods used for poles employed in rigging canoes.

The olomea was a wood much used in rubbing for fire; the ku-kui a wood sometimes used in making the dug-out or canoe; the bark of its roots, mixed with several other things, was used in making the black paint for canoes, and its nuts are strung into torches called ku-kui.6

The paihi is a wood useful as fuel and in house-making. It has a flower similar to that of the Ichua and its bark is used in staining tapa of a black color. The alii is a solid wood used for house posts. The koaie is a strong wood useful as house-timber and in old times used in making shark hooks.

The ohe, or bamboo, which has a jointed stem (pona-pona), was used as fishing poles to take the aku, or any other fish, and formerly its splinters served instead of knives.

The wili-wili is a very buoyant wood, for which reason it is largely used in making surf boards (papa-hee-nalu), and outrigger floats (ama) for canoes. The olapa was a tree from which spears such as were used in bird-liming or bird-snaring were obtained. The lama is a tree whose wood is used in the construction of houses and enclosures for (certain) idols. The awa is the plant whose root supplies the intoxicating drink (so extensively used by the Polynesians).

The ulu or bread-fruit is a tree whose wood is much used in the construction of the doors of houses and the bodies of canoes. Its fruit is made into a delicious poi.7 The ohia, so-called mountain apple, is a tree with scarlet flowers and a fruit agreeable to the taste. The hawane, or loulu-palm, is a tree the wood of which was used for battle spears; its nuts were eaten and its leaves are now used in making hats.

The kou is a tree of considerable size, the wood of which is specially used in making all sorts of platters, bowls and dishes, and a variety of other utensils. The milo8 and the pua were (useful) trees. The niu, coco-palm, is a tree that bears a delicious nut, besides serving many other useful purposes. The (fleshy) stems of the hapuu fern, and the tender shoots of the a-ma-u fern and the i-i-i fern afforded a food that served in time of famine.

The wauke is one of the plants the bark of which is beaten into tapa.9 The wauke had many other uses. The hibiscus, called hau,10 furnished a (light) wood that was put to many uses. Of its bark was made rope or cordage. The ohe-tree produced a soft wood, similar to the kukui (or American bass Translator), and was sometimes used in making stilts, or kuku-luaeo.

The olona and the hopue were plants from whose bark were made lines and fishing nets and a great many other things. The mamaki and the maa-loa were plants that supplied a bark that was made into tapa. The keki and the pala fern were used as food in times of famine. The (hard leaf stalks) of the ama'-u-ma'u fern were used as a stylus for marking tapa (mea palu hole kapa).

The ma'o was a plant whose flower was used as a dye to colored tapa and the loin cloths of the women, etc. The noni was a tree (the bark and roots of) which furnished a yellowish-brown dye (resembling madder) much used in staining the tapa called kua-uia. Its fruit (a drupe) was eaten in time of famine. The (yellow) flowers of the ilima11 were much desired by the women to be strung into leis or garlands.

The hala pandanus or screw pine was a tree the drupe of which was extremely fragrant and was strung into wreaths. Its leaves were braided into mats and sails. The ulei was a tree whose wood was highly valued for its toughness, and of it were made thick, heavy darts ihe-pahee for skating over the ground in a game of that name. It also furnished the small poles with which the mouth of the bag-net, upena-aei, was kept open. The a-e and the po-ola were trees the wood of which was used in spearmaking. The wood of the wala-hee was formerly much used in making a sort of adze (to cut the soft wili-wili wood); it also furnished sticks used in keeping open the mouth of the paki-kii net.

The banana, maia, was a plant that bore a delicious fruit. There were many species of the banana and it had a great variety of uses. The maua was a tree suitable for timber (literally boards or planks papa). The haa, ho-awa, hao, and many other trees 1 have not mentioned in this account were no doubt good for fuel. Besides there were many more trees that I have not mentioned.

The pili a grass much used for thatching houses the koo-koo-lau an herb used in modern times as a tea these and various other plants in the wilderness, such as the i-e, the pala fern, the kupu-kupu, mana, akolea, ama-u-ma'u-fern, etc., etc., were termed nahele-hele12 i.e. weeds or things that spread.

The hono-hono, wandering Jew, the kukae-puaa,13 the kakona-kona, the pili, manienie14 the kulohia, puu-koa, pili-pili-ula, kaluha, the moko-loa, the ahu-awa, the mahiki-hiki, and the kohe-kohe were grasses, mauu.

The popolo, the pakai, the aweo-weo, nau-nau, haio, nena and the palula were cooked and eaten as greens (luau). The gourd was a vine highly prized for the calabashes it produced.

CHAPTER 10

Divisions Of The Ocean

The ancients applied the name kai to the ocean and all its parts. That strip of the beach over which the waves ran after they had broken was called a'e-kai.1

A little further out where the waves break was called poi'na-kai.2 The name pue-one was likewise applied to this place.3 But the same expressions were not used of places where shoal water extended to a great distance, and which were called kaikohala (such as largely prevail for instance at Waikiki).

Outside of the poi-na-kai lay a belt called the kai-hele-ku, or kai-papau, that is, water in which one could stand, shoal water; another name given it was kai-ohua.4

Beyond this lies a belt called kua-au where the shoal water ended; and outside of the kua-au was a belt called kai-au, ho-an, for this belt was kai-kohala.5

Outside of this was a belt called kai-uli, blue sea; squid-fishing sea kai-lu-hee; or sea-of-the flying-fish, kai-malolo; or sea-of-the-opelu, kai-opelu.

Beyond this lies a belt called kai-hi-aku, sea for trolling the aku, and outside of this lay a belt called kai-kohola, where swim the whales, monsters of the sea; beyond this lay the deep ocean, moana, which was variously termed waho-lilo, far out to sea; or lepo, under ground; or Iewa, floating; or lipo, blue-black, which reach Kahiki-moe, the utmost bounds of the ocean. When the sea is tossed into billows they are termed ale. The breakers which roll in are termed nalu. The currents that move through the ocean are called au or wili-au.

Portions of the sea that enter into recesses of the land are kai-hee-nalu,6 that is a surf-swimming region. Another name still kai-o-kilo-hee, that is swimming deep, or sea for spearing squid, or called kai-kuono; that belt of shoal where the breakers curl is called pu-ao; another name for it is ko-aka.

A blow-hole where the ocean spouts up through a hole in the rocks is called a puhi (to blow). A place where the ocean is sucked with force down through a cavity in the rocks is called a mimili, whirlpool; it is also called a mimiki or an aaka

The rising of the ocean-tide is called by such names as ka-pii, rising sea; kai-nui, big sea; kai-piha, full sea; and kai-apo, surrounding sea.

When the tide remains stationary, neither rising nor falling, it is called kai-ku, standing sea; when it ebbs it is called kai-moku, the parted sea; or kai-emi; ebbing sea, or kai-hoi, retiring sea; or kai-make, defeated sea.

A violent, raging surf is called kai-koo. When the surf beats violently against a sharp point of land, that is a cape, lae, it is termed kai-ma-ka-ka-lae.

A calm in the ocean is termed 'a lai or a malino or a pa-e-a-e-a or a pohu.

CHAPTER 11

Eating Under The Kapu System

The task of food-providing and eating under the kapu system in Hawaii nei was very burdensome, a grievous tax on husband and wife, an iniquitous imposition, at war with domestic peace. The husband was burdened and wearied with the preparation of two ovens of food, one for himself and a separate one for his wife.

The man first started an oven of food for his wife, and, when that was done, he went to the house mita and started an oven of food for himself.

Then he would return to the house and open his wife's oven, peel the taro, pound it into poi, knead it and put it into the calabash. This ended the food-cooking for his wife.

Then he must return to mua, open his own oven, peel the taro, pound and knead it into poi, put the mass into a (separate) calabash for himself and remove the lumps. Thus did he prepare his food (ai, vegetable food); and thus was he ever compelled to do so long as he and his wife lived.

Another burden that fell to the lot of the man was thatching the houses for himself and his wife; because the houses for the man must be other than those for the woman. The man had first to thatch a house for himself to eat in and another house as a sanctuary (heiau) in which to worship his idols. And, that accomplished, he had to prepare a third house for himself and his wife to sleep in. After that he must build and thatch an eating house for his wife, and lastly he had to prepare a hale kua, a place for his wife to beat tapa in (as well as to engage in other domestic occupations. TRANSLATOR.) While the husband was busy and exhausted with all these labors, the wife had to cook and serve the food for her husband, and thus it fell that the burdens that lay upon the woman were even heavier than those allotted to the man. During the days of religious tabu, when the gods were specially worshipped, many women were put to death by reason of infraction of some tabu. According to the tabu a woman must live entirely apart from her husband, during the period of her infirmity; she always ate in her own house, and the man ate in the house called mua. As a result of this custom, the mutual love of the man and his wife was not kept warm; the man might use the opportunity to associate with another woman, likewise the woman with another man. It has not been stated who was the author of this tabu that prohibited the mingling of the sexes while partaking of food. It was no doubt a very ancient practice; possibly it dates from the time of Wakea; but it may be subsequent to that.

There is, however, a tradition accepted by some that Wakea himself was the originator of this tabu that restricts eating; others have it that it was initiated by Luhau-kapawa. It is not certain where the truth lies between these two statements. No information on this point is given by the genealogies of these two characters, and every one seems to be ignorant in the matter. Perhaps, however, there are persons now living who know the truth about this matter; if so they should speak out.

It is stated in one of the traditions relating to the gods that the motive of the tabu restricting eating was the desire on the part of Wakea to keep secret his incestuous intercourse with Hoo-hoku-ka-lani. For this reason he devised a plan by which he might escape the observation of Papa; and he accordingly appointed certain nights for prayer and religious observance, and at the same time tabued certain articles of food to women. The reason for this arrangement was not communicated to Papa, and she incautiously consented to it, and thus the tabu was established. The truth of the story I cannot vouch for.

If it was indeed Wakea who instituted this tabu then it was a very ancient one. It was abolished by Kamehameha II, known as Liholiho, at Kailua, Hawaii, on the third or fourth day of October, 1819. On that day the tabu putting restrictions on eating in common ceased to be regarded here in Hawaii. The effect of this tabu, which bore equally on men and women, was to separate men and women, husbands and wives from each other when partaking of food.

Certain places were set apart for the husband's sole and exclusive use; such were the sanctuary in which he worshipped and the eating-house in which he took his food. The wife might not enter these places while her husband was worshipping or while he was eating; nor might she enter the sanctuary or eating-house of another man; and if she did so she must suffer the penalty of death, if her action was discovered.

Certain places also were set apart for the woman alone. These were the hale pea, where she stayed during her period of monthly infirmity at which time it was tabu for a man to associate with his own wife, or with any other woman. The penalty was death if he were discovered in the act of approaching any woman during such a period. A flowing woman was looked upon as both unclean and unlucky (haumia, poino).

Among the articles of food that were set apart for the exclusive use of man, of which it was forbidden the woman to eat, were pork, bananas, cocoanuts, also certain fishes, the ulna, kumu (a red fish used in sacrifice), the niuhi-shark, the sea turtle, the e-a. (the sea-turtle that furnished the tortoise-shell), the pahu, the na ia, (porpoise), the whale, the nuao, hahalua hihimanu, (the ray) and the hailepo. If a woman was clearly detected in the act of eating any of these things, as well as a number of other articles that were tabu, which I have not enumerated, she was put to death.

The house in which the men ate was called the mua; the sanctuary where they worshipped was called heiau, and it was a very tabu place. The house in which the women ate was called the hale ai'na. These houses were the ones to which the restrictions and tabu applied, but in the common dwelling house, hale noa, the man and his wife met freely together.

The house in which the wife and husband slept together was also called hale-moe. It was there they met and lived and worked together and associated with their children. The man, however, was permitted to enter his wife's eating house, but the woman was forbidden to enter her husband's mua.

Another house also was put up for the woman called hale kuku, the place where she beat out tapa-cloth into blankets, into paus for herself, malos for her husband, in fact, the clothing for the whole family as well as for her friends, not forgetting the landlord and chiefs (to whom no doubt these things went in lieu of rent, or as presents. TRANSLATOR.)

The out-of-door work fell mostly upon the man, while the indoor work was done by the woman that is provided she was not a worthless and profligate woman.

I must mention that, certain men were appointed to an office in the service of the female chiefs and women of high station which was termed ai-noa. It was their duty to prepare the food of these chiefish women and it was permitted them at all times to eat in their presence, for which reason they were termed ai-noa to eat in common or ai-puhiu. Back to Contents

CHAPTER 12

The Divisions Of The Year

The seasons and months of the year were appropriately divided and designated by the ancients.

The year was divided into two seasons Kau and Hoo-ilo. Kau was the season when the sun was directly overhead, when daylight was prolonged, when the trade-wind, makani noa'e, prevailed, when days and nights alike were warm and the vegetation put forth fresh leaves. Hoo-ilo was the season when the sun declined towards the south, when the nights lengthened, when days and nights were cool, when herbage (literally, vines) died away.

There were six months in Kau and six in Hoo-ilo. The months in Kau were Iki-iki, answering to May, at which time the constellation of the Pleiades huhui hoku set at sunrise. Kaa-ona, answering to June, in ancient times this was the month in which fishermen got their a-ei nets in readiness for catching the opelu, procuring in advance the sticks to use in keeping its mouth open; Hina-ia-eleele, answering to July, the month in which the ohia fruit began to ripen; Mahoe-mua, answering to August, this was the season when the ohia fruit ripened abundantly; Mahoe-hope, answering to September, the time when the plume of the sugar-cane began to unsheath itself: Ikuwa, corresponding to October, which was the sixth and last month of the season of Kau.

The months in Hoo-ilo were Weleehu, answering to November, which was the season when people, for sport, darted arrows made of the flower-stalk of the sugar-cane; Makalii, corresponding to December, at which time trailing plants died down and the south-wind, the Kona, prevailed; Kaelo, corresponding to January, the time when appeared the enuhe,1 when also the vines began to put forth fresh leaves; Kaulua, answering to February, the time when the mullet, anae, spawned; Nana, corresponding to March, the season when the flying-fish, the malolo, swarmed in the ocean; Welo, answering to April, which was the last of the six months belonging to Hoo-ilo.

These two seasons of six months each made up a year of twelve months,2 equal to nine times forty days and nights, but the ancients reckoned by nights instead of days.

There were thirty nights and days in each month; seventeen of these days had compound names (inoa huhui) and thirteen had simple names (inoa pakahi) given to them.

These names were given to the different nights to correspond to the phases of the moon. There were three phases ano marking the moon's increase and decrease of size, namely, (1) Ithe first appearance of the new moon in the west at evening: (2) The time of full-moon when it stood directly overhead (literally, over the island) at midnight. (3) The period when the moon was waning, when it showed itself in the east late at night. It was with reference to these three phases of the moon that names were given to the nights that made up the month.

The first appearance of the moon at evening in the west marked the first day of the month. It was called Hilo on account of the moon's slender, twisted form.

The second night when the moon had become more distinct in outline was called Hoaka; and the third when its form had grown still thicker, was called Ku-kahi; so also the fourth was called Ku-lua. Then came Ku-kolu, followed by Ku-pau which was the last of the four nights named Ku.

The 7th, when the moon had grown still larger, was called Ole-ku-kahi; the 8th, Ole-ku-lua; the qth, Olc-ku-kolu; the 10th, Olepau3 making four in all of these nights, which, added to the previous four, brings the number of nights with compound names up to eight.

As soon as the sharp points of the moon's horns were hidden the name Huna (hidden) was given to that night the nth. The 12th night, by which time the moon had grown still more full, was called Mohalu. The 13th night was called Hua because its form had then become quite egg-shaped (hua an egg); and the 14th night, by which time the shape of the moon had become distinctly round, was called Akua (God), this being the second night in which the circular form of the moon was evident.

The next night, the I5th, had two names applied to it. If the mocn set before daylight ke ao ana it was called hoku palemo, sinking star, but if when daylight came it was still above the horizon it was called hoki ili, stranded star.

The second of the nights in which the moon did not set until after sunrise 16th was called Mahea-lani. When the moon's rising was delayed until after the darkness of night had set in, it was called Kulua, and the second of the nights in which the moon made its appearance after dark was called Laau-ku-kahi (18th); this was the night when the moon had so much waned in size as to again show sharp horns.

The 19th showed still further waning and was called Laau-ku-lua; then came Laau-pan (2Oth), which ended this group of compound names, three in number. The name given to the next night of the still waning moon was Ole-ku-kahi. Then in order came Ole-ku-lua and Ole-pau, making three of this set of compound names, (21st, 22nd and 23rd).

Still further waning, the moon was called Kaloa-ku-kahi; then Kaloa-ku-lua; and lastly, completing this set of compound names, three in number, Kaloa-pau, (24th, 25th and 26th).

The night when the moon rose at dawn of day (27th) was called Kane, and the following night, in which the moon rose only as the day was breaking (28th), was called Lono. When the moon delayed its rising until daylight had come it was called Mauli, fainting;4 and when its rising was so late that it could no longer be seen for the light of the sun, it was called Muku cut off. Thus was accomplished the thirty5 nights and days of the month.6

Of these thirty days some were set apart as tabu, to be devoted to religious ceremonies and the worship of the gods. There were four tabu-periods in each moon.

The first of these tabu-periods was called that of Ku, the second that of Hua, the third that of Kaloa (abbreviated from Kana-loa), the fourth that of Kane.

The tabu of Ku included three nights; it was imposed on the night of Hilo and lifted on the morning of Kulua. The tabu of Hua included two nights; it was imposed on the night of Mohalu and lifted on the morning of Akua. The tabu of Kaloa included two nights; it was imposed on the night of Ole-pau and raised on the morning of Kaloa-ku-lua. The tabu of Kane included two nights; being imposed on the night of Kane and lifted on the morning of Mauli.

These tabu-seasons were observed during eight months of the year, and in each year thirty-two days7 were devoted to the idolatrous worship of the gods.

There were now four months devoted to the observances of the Makahiki, during which time the ordinary religious ceremonies were omitted, the only ones that were observed being those connected with the Makahiki festival. The prescribed rites and ceremonies of the people at large were concluded in the month of Mahoe-hope. The keeoers of the idols, however, kept up their prayers and ceremonies throughout the year.

In the month of Ikuwa the signal was given for the observance of Makahiki, at which time the people rested from their prescribed prayers and ceremonies to resume them in the month of Kau-lua. Then the chiefs and some of the people took up again their prayers and incantations, and so it was- during every period in the year.

CHAPTER 13

The Domestic And Wild Animals

It is not known by what means the animals found here in Hawaii reached these shores, whether the ancients brought them, whether the smaller animals were not indigenous, or where indeed the wild animals came from.

If they brought these little animals, the question arises why they did not also bring animals of a larger size.

Perhaps it was because of the small size of the canoes in which they made the voyage, or perhaps because they were panic stricken with war at the time they embarked, or because they were in fear of impending slaughter, and for that reason they took with them only the smaller animals.

The hog1 was the largest animal in Hawaii nei. Next in size was the dog; then came tame fowls, animals of much smaller size. But the wild fowls of the wilderness, how came they here? If this land was of volcanic origin, would they not have been destroyed by fire?

The most important animal then was the pig (puaa), of which there were many varieties. If the hair was entirely black, it was called hiwa paa; if entirely white, haole; if it was of a brindled color all over, it was ehu; if striped lengthwise, it was olomea.

If reddish about the hams the pig was a hulu-iwi; if whitish about its middle it was called a hahei; if the bristles were spotted, the term kiko-kiko was applied.

A shoat was called poa (robbed); if the tusks were long it was a pu-ko'a. A boar was termed kea,2 a young pig was termed ohi.

Likewise in regard to dogs, they were classified according to the color of their hair; and so with fowls, they were classified and named according to the character of their feathers. There were also wild fowl.

The names of the wild fowl are as follows, the nene (goose). The nene, which differs from all other birds, is of the size of the Muscovy duck, has spotted feathers, long legs and a long neck. In its molting season, when it comes down from the mountains, is the time when the bird-catchers try to capture it in the uplands, the motive being to obtain the feathers, which are greatly valued for making kahilis. Its body is excellent eating.

The alala (Corvus hawaiiensis) is another species, with a smaller body, about the size perhaps of the female of the domestic fowl. Its feathers are black, its beak large, its body is used for food. This bird will sometimes break open the shell of a water gourd (hue-wai). Its feathers are useful in kahili-making. This bird is captured by means of the pole or of the snare.

The pueo, or owl, and the io resemble each other; but the pueo has the larger head. Their bodies are smaller in size to that of the alala. Their plumage is variegated (striped), eyes large (and staring), claws sharp like those of a cat. They prey upon mice and small fowl. Their feathers are worked into kahilis of the choicest descriptions. The pueo is regarded as a deity and is worshipped by many. These birds are caught by means of the bird-pole (kia) by the use of the covert,3 or by means of the net. 4

The moho is a bird that does not fly, but only moves about in thickets because its feathers are not ample enough (to give it the requisite wing-power). It has beautiful eyes. This bird is about the size of the alala; it is captured in its nesting-hole and its flesh is used as food. This bird does not visit (or swim in) the sea, but it lives only in the woods and coverts, because (if it went into the ocean), its feathers would become heavy and watersoaked.

I will not enumerate the small wild fowl, some of them of the size of young chickens, and some still smaller: the o-u is as large as a small chicken, with feathers of a greenish color; it is delicious eating and is captured by means of bird-lime.

Another bird is the omao, in size about like the o-u. Its feathers are black, it is good eating and is captured by means of bird-lime or with the snare.

The o-o and the mamo are birds that have a great resemblance to each other. They are smaller than the o-u, have black feathers, sharp beaks, and are used as food. Their feathers are made up into the large royal kahilis. Those in the axillae and about the tail are very choice, of a golden color, and are used in making the feather cloaks called ahu-ula which are worn by (the aliis as well as by) warriors as insignia in time of battle (and on state occasions of ceremony or display. TRANSLATOR.) They were also used in the making of leis (necklaces and wreaths) for the adornment of the female chiefs and women of rank, and for the decoration of the makahiki-idol. These birds have many uses, and they are captured by means of bird-lime and the pole.

The i-i-wi; the feathers of this bird are red, and used in making ahu-ula. Its beak is long and its flesh is good for food. It is taken by means of bird-lime. The apa-pane and the akihi-polena also have red feathers. The ula is a bird with black feathers, but its beak, eyes, and feet are red. It sits sidewise on its nest (he punana moe aoao kona). This bird is celebrated in song. While brooding over her eggs she covered them with her wings, but did not sit directly over them. The u-a is a bird that resembles the o-u. The a-ko-he-kohe is a bird that nests on the ground.

The mu is a bird with yellow feathers. The ama-kihi and akilu-a-loa have yellow plumage; they are taken by means of bird-lime. Their flesh is fine eating.

The ele-paio 5 (chasiempis): this bird was used as food. The i-ao resembles the moho; in looking it directs its eyes backwards. In this list comes the kaka-wahie (the wood-splitter). The ki is the smallest of these birds. They all have their habitat in the woods and do not come down to the shore.

The following birds make their resort in the salt and fresh water-ponds. The alae (mud-hen, Gallinula chloropus) has blue-black feathers, yellow feet, red forehead, but one species is white about the forehead (Fulica alae.) This bird is regarded as a deity, and has many worshippers. Its size is nearly that of the domestic fowl, and its flesh is good eating (gamey, but very tough). Men capture it by running it down or by pelting it with stones.

The koloa (Muscovy duck) has spotted feathers, a bill broad and flat, and webbed feet. Hunters take it by pelting it with stones or clubbing it. It is fine eating. The aukuu, (heron), has bluish feathers and a long neck and beak. In size it is about the same as the pueo, or owl. This bird makes great depredations by preying upon the mullet (in ponds.) The best chance of capturing it would be to pelt it with stones.

The kukuluaeo (stilts one of the waders), has long legs and its flesh is sweet. It may be captured by pelting it with stones. The kioea (one of the waders) is excellent eating. The kolea (plover). It is delicious eating. In order to capture it, the hunter calls it to him by whistling with his fingers placed in his mouth, making a note in imitation of that of the bird itself.

The following birds are ocean-divers (luu-kai): The ua-u (Procellaria alba). Its breast is white, its back blue-black; it has a long bill of which the upper mandible projects beyond the lower. It is delicious eating. Its size is that of the io. The kiki the ao and the lio-lio resemble the uau, but their backs are bluish. Their flesh is used as food. They are captured with nets and lines.

The o-u-o-u: This bird is black all over; it is of a smaller size than the uau and is fair eating; it is caught by means of a line. The puha-aka-kai-ea is smaller than the o-u-o-u; its breast is white, its back black; it is caught with a net and is good for food.

The koae (tropic bird, "boatswain bird," "marlin spike"): This bird is white (with a pinkish tinge) all over; it has long tail-feathers which are made into kahilis; it is of the same size as the u-a-u, and is fit for food (very fishy). The o-i-o (Anous stolidtis) has speckled feathers like the ne-ne; it is of the same size as the u-a-n and is good eating. All of these birds dwell in the mountains by night, but during the day they fly out to sea to fish for food.

I will now mention the birds that migrate (that are of the firmament, mai ke lewa mai lakou.) The ka-u pu: Its feathers are black throughout, its beak large, its size that of a turkey. The na-u-ke-wai is as large as the ka-u pu. Its front and wings are white, its back is black. The a is as large as the ka-u-pu, its feathers entirely white. The moli is a bird of about the size of the ka-u-pu. The iwa is a large bird of about the size of the ka-u-pu: its feathers, black mixed with gray, are used for making kahilis. The plumage of these birds is used in decorating the Makahiki idol. They are mostly taken at Kaula and Nihoa, being caught by hand and their flesh is eaten. The noio is a small bird of the size of the plover, its forehead is white. The kala (Sterna panaya) resemble the noio. These are all eatable, they are sea-birds.

The following are the flying things (birds, manu) that are not eatable: the o-pea-pea or bat, the pinao or dragon-fly, the okai (a butterfly), the lepe-lepe-ahina (a moth or butterfly), the pu-lele-hua (a butterfly), the nalo or common house-fly, the nalo-paka or wasp. None of these creatures are fit to be eaten. The uhini or grasshopper, however, is used as food.

The following are wild creeping things: the mouse or rat, (iole), the makaula (a species of dark lizard), the elelu, or cockroach, the poki-poki (sow-bug), the koe (earth-worm), the lo (a species of long black bug, with sharp claws), the aha or ear-wig, the puna-wele-wele or spider, the lalana (a species of spider), the nuhe or caterpillar, the poko (a species of worm, or caterpillar), the nao-nao or ant, the mu (a brown-black bug or beetle that bores into wood), the kua-paa (a worm that eats vegetables), the uku-poo or head-louse, the uku-kapa, or body-louse.

Whence come these little creatures? From the soil no doubt; but who knows ? The recently imported animals from foreign lands, which came in during the time of Kamehameha I, and as late as the present time, that of Kamehameha III, are the following: the cow (bipi, from beef), a large animal, with horns on its head; its flesh and its milk are excellent food.

The horse (lio), a large animal. Men sit upon his back and ride; he has no horns on his head. The donkey (hoki), and the mule (piula); they carry people on their backs. The goat (kao), and the sheep (hipa), which make excellent food. The cat (po-poki, or o-au6 and the monkey (keko), the pig (puaa) 7 and the dog (ilio).8

These are animals imported from foreign countries.

Of birds brought from foreign lands are the turkey, or palahu, the koloa8, or duck, the parrot or green-bird (manu omaomao), and the domestic fowl (moa), which makes excellent food.

There are also some flying things that are not good for food: such as the mosquito (makika), the small roach (elelu liilii), the large flat cock-roach (elelu-papa) , the flea (uku-lele (jumping louse). The following are things that crawl: the rabbit or iole-lapaki, which makes excellent food, the rat or iole-nui, the mouse or iole-liilii, the centipede (kanapi), and the moo-niho-awa (probably the scorpion, for there are no serpents in Hawaii). These things are late importations; the number of such things will doubtless increase in the future.

CHAPTER 14

Articles Of Food And Drink In Hawaii

The food staple most desired in Hawaii nei was the taro (kalo), Arum esculentum. When beaten into poi, or made up into bundles of hard poi, called pai-ai, omao, or holo-ai,1 it is a delicious food. Taro is raised by planting the stems. The young and tender leaves are cooked and eaten as greens called lu-aiit likewise the stems under the name of ha-ha. Poi is such an agreeable food that taro is in great demand. A full meal of poi, however, causes one to be heavy and sleepy.

There are many varieties of taro.2 These are named according to color, black, white, red and yellow, besides which the natives have a great many other names. It is made into kulolo (by mixture with the tender meat of the cocoanut), also into a draught termed apu which is administered to the sick; indeed its uses are numerous.

The sweet potato (uala), (the Maori kumara), was an important article of food in Hawaii nei; it had many varieties3 which were given names on the same principle as that used in naming taro, viz: white, black, red, yellow, etc.

The uala grows abundantly on the kula lands, or dry plains. It is made into a kind of poi or eaten dry. It is excellent when roasted, a food much to be desired. The body of one who makes his food of the sweet potato is plump and his flesh clean and fair, whereas the flesh of him who feeds on taro-poi is not so clear and wholesome.

The u-ala ripens quickly, say in four or five months after planting, whereas the taro takes twelve months to ripen. Animals fed on the sweet potato take on fat well; its leaves (when cooked) are eaten as greens and called palula. Sweet potato sours quickly when mixed into poi, whereas poi made from taro is slow to ferment. The sweet potato is the chief food-staple of the dry, upland plains. At the present time the potato is used in making swipes. The sweet potato is raised by planting the stems.

The yam, or uhi (Dioscorea) is an important article of food. In raising it, the body of the vegetable itself is planted. It does not soon spoil if uncooked. It is not made up into poi, but eaten while still warm from the oven, or after roasting. The yam is used in the preparation of a drink for the sick.

The ulu or bread-fruit is very much used as a food by the natives, after being oven-cooked or roasted; it is also pounded into a delicious poi, pepeiee. It is propagated (by planting shoots or scions.)

The banana (mai'a) was an important article of food, honey-sweet, when fully ripe, and delicious when roasted on the coals or oven-cooked, but it does not satisfy. It was propagated from offshoots.

The ohia or "mountain apple" was a fruit that was much eaten raw. It was propagated from the seed.4 The squash is eaten only after cooking.

The following articles were used as food in the time of famine: the ha-pu-u fern (the fleshy stem of the leaf-stalk); the ma'u and the i-i-i (the pithy flesh within the woody exterior). These (ferns) grow in that section of the mountain-forest called wao-maukele. The outer woody shell is first chipped away with an ax, the soft interior is then baked in a large underground oven overnight until it is soft when it is ready for eating. But one is not really satisfied with such food.

The ti5 (Cordyline terminalis) also furnishes another article of food. It grows wild in that section of the forest called wao-akua. The fleshy root is grubbed up, baked in a huge, underground oven overnight until cooked. The juice of the ti-root becomes very sweet by being cooked, but it is not a satisfying food.

The pi-u (a kind of yam,) is a good and satisfying food when cooked in the native oven. It is somewhat like the sweet-potato when cooked. The ho-i (Helmia bulbifera): this is a bitter fruit. After cooking and grating, it has to be washed in several waters, then strained through cocoanut web (the cloth-like material that surrounds the young leaves. TRANSLATOR) until it is sweet. It is then a very satisfying food.

The pala-fern (Marattia) also furnished a food. The base of the leaf-stem was the part used; it was eaten after being oven-cooked. This fern grows wild in the woods.

The pia (Tacca pinnatifida) is another food-plant, of which the tubers are planted. When ripe the tubers are grated while yet raw by means of rough stones, mixed with water and then allowed to stand until it has turned sweet, after which it is roasted in bundles and eaten. The wild pea, papapa, the nena, the koali6 (Ipomoea tuberculata) were all used as food in famine times.

Among the kinds of food brought from foreign countries are flour, rice, Irish potatoes, beans, Indian corn, squashes and melons, of which the former are eaten after cooking and the latter raw.

In Hawaii nei people drink either the water from heaven, which is called real water (wai maoli), or the water that comes from beneath the earth, which is (often) brackish. Awa was the intoxicating drink of the Hawaiians in old times; but in modern times many new intoxicants have been introduced from foreign lands, as rum, brandy, gin.

People also have learned to make intoxicating swipes from fermented potatoes, watermelon, or the fruit of the ohia.7

|

||

| Back to Mēheuheu (customs) | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

| History | Atlas | Culture | Language | Links | ||